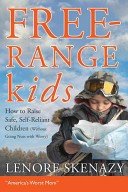

Free-Range Kids: Giving Our Children the Freedom We Had Without Going Nuts with Worry, by Lenore Skenazy (Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 2009)

Free-Range Kids: Giving Our Children the Freedom We Had Without Going Nuts with Worry, by Lenore Skenazy (Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 2009)

Paperback subtitle: How to Raise Safe, Self-Reliant Children (Without Going Nuts with Worry)

I've been following (and blogging about) Free-Range Kids for quite a while now, so it's about time I finally read the book. First off, in case you don't bother to read the rest of this post: Get a hold of a copy of this book and read it. If you are tempted to dismiss the free-range movement as crazy, irresponsible parenting, this will reassure you. If you're already sold on this idea, it will open your eyes to how we got to the point of needing it.

Being so familiar with the Free-Range Kids blog, and even having made some contributions myself, I thought I knew what to expect from the book. Boy was I wrong.

I was shocked.

It was a revelation nearly as great as the one I had seven years ago, when I discovered the sea change that had taken place in childbirth practices since our children were born.

Lenore Skenazy, dubbed "America's Worst Mom" (google it) and made the center of a media storm for daring to let her New York City-bred, public transit-savvy, nine-year-old son take a trip on the subway by himself; Lenore Skenazy, Ms. Free-Range Kids herself, is ...

Tame.

Tame. There's no other word for it. That someone as mild and safety-conscious as Skenazy is considered dangerously revolutionary shows just how much has changed in the last 30 years. She sings the praises of car seats, never suggesting that, for example, Pennsylvania's laws requiring them for children up to eight years old borders on the ridiculous. She wouldn't hear of letting a kid ride a bike without a helmet. She trusts government studies and mainstream medical associations like the American Academy of Pediatrics, never questioning the back-to-sleep campaign, nor the current childhood vaccination schedule. I'm not saying she's necessarily wrong (though I certainly don't always agree), but she's hardly radical.

Here's an example of what she's fighting, where she stands, and a scenario many would call crazy (though I call it wonderful). Let's begin with her description of the Lou and Lou Safety Patrol videos available online from Playhouse Disney.

The Lous are a brother and sister of maybe three or four years old who call themselves the "Safety Patrol." They spring into action when their six- or sevenish sister actually wants to make their dad breakfast for his birthday.

"Not so fast!" squeak the safety-loving sibs as their sister tries to cook some eggs. "Never touch a pot or pan on the stove. Let a grown-up." They plunk an orange safety cone in front of the stove to keep her away.

Undaunted, the sister drifts down the counter and reaches for a knife. "You have a safety violation!" chime her bad cop-bad cop siblings. "You should always stay away from sharp knives and let a grown-up help if you need to slice something."

Skenazy's response?

Now, I'm not saying that six-year-olds make the ideal short-order chefs and let's let 'em loose near the french-fry vat. But the constant refrain of "Get a grown-up! Let a grown-up!" reinforces the whole idea that, rather than trying to learn any kind of real-world skill, kids should sit back and leave it all up to the adults."

Of course, she's right, and apparently it needs to be said. But contrast this with a scene I observed on a recent visit with our daughter's family.

Our granddaughter, barely two years old, is helping cut vegetables for an omelet. With her small paring knife, she hacks contentedly at a mushroom while Mom works on the rest of breakfast. She has been begging for months to be allowed to do this job, and her mother has recently decided she has the coordination to begin her apprenticeship. At her current skill level—about 10 minutes per mushroom—her contributions are small, but her brothers, ages four and six, began at the same age and are now safe, effective, and enthusiastic vegetable choppers. And stove users. (Not to mention that the six-year-old is a dab hand with an electric drill, but that's another story.)

Now that might be considered radical—but 40 years ago I babysat a couple of British boys, ages three and five, who fixed their own dinner, including heating vegetables on the stove. I wonder what their parents thought about their American neighbors' kids—and vice versa.

Read the book, and you'll get a glimpse of what children are up against these days. Read about the sixth grader, assigned to design and execute a "free-range" project. Feel her fear of the strangers on the sidewalk as she walks solo to the grocery store (half a mile away from home) for the first time in her life, and feel her humiliation when one of them asks, "Where is your mommy, young lady?" Sixth grade. Since Skenazy neglects to mention that this was a six-year-old prodigy, I assume the girl walking without her mommy was at least 11 years of age.

Or consider this report, written by another girl from the same middle school class. She had taken her dog to the vet, where at first she was merely ignored.

"Good morning," Emma said and the vet turned sharply around.

"Hi. Where is your mommy, little girl?" Her sharp voice echoed against the green walls. A little surprised by the vet's tone, Emma answered that her mom was at work. The vet looked troubled. "Do you have your mom's phone number with you? I might have to give her a call." She quickly dialed the given number. "Hi! This is Dr. S. Your daughter is here. Can I actually give her instructions?"

In the end, the vet wrote a page of doggie dos and don'ts and handed it to Emma. "Oh wait!" The vet snatched the letter back. "Can you read?"

I could quote pages and pages of this kind of story. But I won't. You'll enjoy them much more if you read the book, because Skenazy is the kind of writer I want to be. She writes well, she writes seriously—and at the same time she's so funny I'd have enjoyed the book even if I didn't agree with the premise. I know that, because I still laughed in the sections were I disagree vehemently with what she says.

Read about how DVD's of the original Sesame Street shows are labelled "intended for adults"—because they "model the wrong behavior," e.g. "Alistair Cookie" with his pipe, children playing in a vacant lot, a girl riding her tricycle without a helmet. Take a look at how television (news and other programming) begat and nurtured a culture of fear and a totally skewed view of what's dangerous in our lives—and what's not.

TV historian [Robert] Thompson [says], "I don't think there's a single episode of Law and Order that could have even been shown before 1981." That's because, until then, [its] graphic images were taboo. In fact, they were the stuff of porn.

[O]nce we see horrific images, only half of our brain takes the time to say, "Wow. That makeup person did an incredible job with those puncture wounds." ... The other half of our brain just takes in those gruesome images wholesale and files them under "Sick World, comma, What we live in."

In his book The Science of Fear, Daniel Gardner explains that once an image gets into [the] "reptilian" part of the brain, not only can you not shake it, you also can't extricate it from all the other images and feelings jostling around in there, either. After all, it's only been the last hundred years or so that the brain has started seeing realistic-looking images (TV, movies) that weren't directly applicable to its fate (lions, spears). So it hasn't figured out yet how to separaae the real form the manufactured.

Thanks to the news media, we have absorbed a completely false view of the chances a child will be abducted and murdered by a stranger.

According to Warwick Cairns, who wrote the book How to Live Dangerously: if you actually wanted your child to be kidnapped and held overnight by a stranger, how long would you have to keep her outside, unattended, for this to be statistically likely to happen?

About seven hundred and fifty thousand years.

How about the Hallowe'en candy scare that altered trick-or-treating forever? Razor blades in apples, poisoned candy? The truth?

There has never been a single substantiated instance of any child dying from a stranger's poisoned Halloween candy.

Never.

And here's one after my own heart: The danger of salmonella from eating raw cookie dough? Much too low to deprive our children of one of life's glories.

The next excited me, too, because even 50 years ago eating snow was a forbidden pleasure.

Joel Forman, a member of the American Academy of Pediatrics committee on environmental health, was quoted as saying, "I can say that I'm not aware of any clinical reports of children becoming ill from eating snow. And I looked."

On the other hand, when I was a child the snow was picking up residue from atomic bomb tests, so I can't blame my parents for a little paranoia.

If you study the odds, the one thing you will not let your children do is go anywhere in an automobile, car seat or no. But that's not going to happen, which may explain why we prefer to avoid risk calculations.

Our misguided hysteria is not all the media's fault. Lawyers can take a hefty share of the blame, as many bizarrely restrictive policies are the direct result of lawsuit-phobia. Such as school buses that will not drop children off unless they are met by a "responsible adult"—if not, the child is taken back to school. And the demise of really exciting playground equipment, and diving boards at swimming pools. Here's one for the record books: a release form from California.

I fully understand my minor's participation may involve risk of serious injury or death.

That's for a piano recital. What are they afraid of? The ghost of Beethoven causing havoc over a mangled Für Elise?

While we're assigning blame, let's not forget greedy capitalists. Like the "professional babyproofer" who promoted toilet lid locks on national television by intoning, "On average two children a week die in toilets." The stats from the Consumer Product Safety Commission on accidental drowning in toilets of children under five? Four per year. Or the sellers of the "Thudguard," a helmet to protect toddlers learning to walk. Dr. F. Sessions Cole, chief medical officer at the St. Louis Children's Hospital, reports that of their sixty-five to seventy thousand patients per year, exactly none were toddlers with significant head trauma from instability while learning to walk. (No statistics available on the instability caused by wearing a helmet while trying to learn to walk.)

There are hucksters everywhere happy to take advantage of parents with more money than sense. Don't trust your own hand to make sure the bath water is safe for your child? Buy a turtle bath toy that will flash, "too hot!" Don't trust your child's natural padding (and unnatural diaper padding) to protect his little bottom from falls while he learns to walk? Someone will sell you a harness to hold him up while he toddles. Too busy or too frightened to let your little girl experience the joys of water firsthand? "Baby Neptune exposes little ones to the wonders of water in their world—whether they're stomping in the rain, splashing in the bathtub, playing 'catch me if you can' with the tide on the beach...." And how does Baby Neptune accomplish this feat, safely and dryly? It's a video of other children doing all those wonderful wet things.

Still another culprit inciting us to terror: the busybodies who not only encapsulate their own children, but feel it their duty to do the same for yours, even to the extent of reporting you (anonymously, of course) to Child Protective Services. Unfortunately, as I learned on the FRK blog, that's not a baseless fear. But, like much of what terrifies us, it is an uncommon occurrence. More common are the other parents who will merely try to shame you for taking the shackles off your kids. As John Holt said,

One of the saddest things I’ve learned in my life, one of the things I least wanted to believe and resisted believing for as long as I could, was that people in chains don’t want to get them off, but want to get them on everyone else. “Where are your chains?” they want to know. “How come you’re not wearing chains? Do you think you are too good to wear them? What makes you think you’re so special?”

Skenazy has some good advice for this problem, too.

Blamers thrive on shame. Take away their power. Do not be ashamed of making parenting choices based on who your kid is, rather than on what the neighbors will say. Why are they talking about you anyway?

Did I say Lenore Skenazy's book was tame? Well, yes. It is. But that doesn't mean it's not vitally important, on the order of Last Child In the Woods. If you have young children, read it. If your children are grown, read it anyway; it will make you laugh, and your grandchildren will thank you. But don't waste any time bemoaning what you wish you had done differently. I've done more than my share of that, and it's counterproductive. That's another message of this book: Children are amazingly resilient, and their well-being does not hinge on every parental decision we make. It really doesn't. We don't have that much power—and we shouldn't want it.

One more quote and the sticky notes bristling from the pages of Free-Range Kids will be gone. Free-ranging is not about irresponsible parenting, any more than unschooling is about leaving children without educational support and guidance. (emphasis mine)

Free-Range Parents are not hands off. We give our children the tools to be safe and independent, and we listen to them too.

It's amazing how easy it is for me to write it off since currently so much doesn't apply to us: we don't live in the US, we don't have a car, we have two very dangerous (i.e. exciting) playground within a few paces of our apartment, and 11-year-olds hang out unattended downtown and night (okay, so that's not an example of how things are better here . . .), and elementary aged kids ride public transportation to school alone. We'll be in for some major reverse culture shock if we ever move back to the States.

You'd be setting a great example. :)

There are definitely places in the book you would relate to, though. She whacks emphatically on the guilt trips put on mothers by such books as What to Expect When You're Expecting and all the "how to have a perfect pregnancy, labor, delivery, nursing, and childhood experience, and if you don't it's all your fault" books.

We get to sign release forms at BounceU, a very fun place for kids where all the floors, walls and obstructions are essentially giant balloons.

I laughed out loud at much of the book, too. She does write very well.