At Heather's suggestion, I am now reading Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race, by Margot Lee Shetterly. We'd enjoyed the movie version very much, but so far the book is orders of magnitude better. Especially if you don't mind a bit of math and the technical aspects of airplanes and flight. Even if you do, it's a well-written story, and it covers so much more than the movie.

I'm a third of the way through the book, and have just now reached the point of Sputnik. It would be hard for the story to get more interesting, however, at least for me. I see in the stories of WWII-era female mathematicians, black and white, a possible glimpse into that stage of my own mother's life, of which I know very little. She graduated in math from Duke University in 1946, and worked as an Engineering Assistant at General Electric for a few years after that.

There's enough to say about my mother's story to warrant its own post, so it will have to wait. In the meantime, here's an excerpt of one of my favorite tales from the book.

For Katherine, being selected to rotate through Building 1244, the kingdom of the fresh-air engineers, felt like an unexpected bit of fortune, however temporary the assignment might prove to be. She had been elated simply to sit in the pool and calculate her way through the data sheets assigned by Mrs. Vaughan. But being sent to sit with the brain trust located on the second floor of the building meant getting a close look at one of the most important and powerful groups at the laboratory. Just prior to Katherine’s arrival, the men who would be her new deskmates, John Mayer, Carl Huss, and Harold Hamer, had presented their research on the control of fighter airplanes in front of an audience of top researchers, who had convened at Langley for a two-day conference on the latest thinking in the specialty of aircraft loads.

With just her lunch bag and her pocketbook to take along, Katherine “picked up and went right over” to the gigantic hangar, a short walk from the West Computing office. She slipped in its side door, climbed the stairs, and walked down a dim cinderblock hallway until she reached the door labeled Flight Research Laboratory. Inside, the air reeked of coffee and cigarettes. Like West Computing, the office was set up classroom-style. There were desks for twenty. Most of the people in the space were men, but interspersed among them a few women consulted their calculating machines or peered intently at slides in film viewers. Along one wall was the office of the division chief, Henry Pearson, with a station for his secretary just in front. The room hummed with pre-lunch activity as Katherine surveyed it for a place to wait for her new bosses. She made a beeline for an empty cube, sitting down next to an engineer, resting her belongings on the desk and offering the man her winning smile. As she sat, and before she could issue a greeting in her gentle southern cadence, the man gave her a silent sideways glance, got up, and walked away.

This is where my brain threw an interrupt, and I paused in my reading. I'm willing to bet that my reaction was quite different from that of most people reading about the encounter. The obvious response is to label the engineer a racist, sexist bigot—of which there are certainly many examples in the book. But what I saw in his reaction was not a bigot, but an engineer.

The people at Langley were not just engineers, mathematicians, and physicists; they were some of the brightest of their species in the country. That kind of intelligence is often accompanied by what in my day we called "quirkiness." I know that not all engineers are alike, any more than all black female mathematicians are alike. But I know something about engineers. There are five generations of engineers in my family, and a goodly number of mathematicians. My father was a mechanical engineer with a master's degree in physics, and he worked for the General Electric Company's research laboratory in Schenectady, New York. With its abundance of mathematicians, physicists, and above all engineers, living in Schenectady was in its heyday like living in Silicon Valley or Seattle today. And no doubt much like the world of the the Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory in Hampton, Virginia. It was the air I breathed, the water I swam in. It wasn't until we moved to Philadelphia's Main Line when I was in high school that I encountered a broader world.

So when I read of the encounter between Katerhine and the engineer, here's what I saw: Not the clash of race, sex, or social position, but this: An engineer is sitting by himself in his own world, working on a project, his thoughts very far away, when another person unexpectedly invades his space, looks right at him, smiles, and even makes eye contact. His concentration is broken, his train of thought is derailed, and he flees to safer territory. Or maybe not—but that's the scenario as I imagined it.

The real story is better.

Katherine watched the engineer disappear. Had she broken some unspoken rule? Could her mere presence have driven him away? It was a private and unobtrusive moment, one that failed to dent the rhythm of the office. But Katherine’s interpretation of that moment would both depend on the events in her past and herald her future. Bemused, Katherine considered the engineer’s sudden departure. The moment that passed between them could have been because she was black and he was white. But then again, it could have been because she was a woman and he was a man. Or maybe the moment was an interaction between a professional and a subprofessional, an engineer and a girl.

Outside the gates, the caste rules were clear. Blacks and whites lived separately, ate separately, studied separately, socialized separately, worshipped separately, and, for the most part, worked separately. At Langley, the boundaries were fuzzier. Blacks were ghettoed into separate bathrooms, but they had also been given an unprecedented entrée into the professional world. Some of Goble’s colleagues were Yankees or foreigners who’d never so much as met a black person before arriving at Langley. Others were folks from the Deep South with calcified attitudes about racial mixing. It was all a part of the racial relations laboratory that was Langley, and it meant that both blacks and whites were treading new ground together. The vicious and easily identifiable demons that had haunted black Americans for three centuries were shape-shifting as segregation began to yield under pressure from social and legal forces. Sometimes the demons still presented themselves in the form of racism and blatant discrimination. Sometimes they took on the softer cast of ignorance or thoughtless prejudice. But these days, there was also a new culprit: the insecurity that plagued black people as they code-shifted through the unfamiliar language and customs of an integrated life.

Katherine understood that the attitudes of the hard-line racists were beyond her control. Against ignorance, she and others like her mounted a day-in, day-out charm offensive: impeccably dressed, well-spoken, patriotic, and upright, they were racial synecdoches, keenly aware that the interactions that individual blacks had with whites could have implications for the entire black community. But the insecurities, those most insidious and stubborn of all the demons, were hers alone. They operated in the shadows of fear and suspicion, and they served at her command. They would entice her to see the engineer as an arrogant chauvinist and racist if she let them. They could taunt her into a self-doubting downward spiral, causing her to withdraw from the opportunity that Dr. Claytor had so meticulously prepared her for.

But Katherine Goble had been raised not just to command equal treatment for herself but also to extend it to others. She had a choice: either she could decide it was her presence that provoked the engineer to leave, or she could assume that the fellow had simply finished his work and moved on. Katherine was her father’s daughter, after all. She exiled the demons to a place where they could do no harm, then she opened her brown bag and enjoyed lunch at her new desk, her mind focusing on the good fortune that had befallen her.

Within two weeks, the original intent of the engineer who walked away from her, whatever it might have been, was moot. The man discovered that his new office mate was a fellow transplant from West Virginia, and the two became fast friends.

It was a genealogy moment. I was thinking about Memorial Day, and that it would be good to write a post honoring my own ancestors. I couldn't think of anyone! Oh, there were plenty of ancestors who fought in wars, from before our country was founded through World War II, including both sides of the Civil War, but none who died in their service, which is what Memorial Day is all about.

"How odd," I thought. "Was our family just extraordinarily lucky?"

And then I laughed at myself. It's not odd at all. Who is it, mostly, who dies in wars? Young men! Men who go off to war early in life and don't come back, never to have the opportunity to become ancestors.

If we were to honor our ancestors who suffered the loss of a child in service to their country, that would be a very different story.

As a genealogist, I've read a lot of obituaries, and written a couple myself. I don't think I've ever published one for someone I wasn't related to, but Tucker Carlson's obituary for his father, which I copy here from his X post, deserves special mention.

I very much enjoy listening to Tucker's interviews, and if I hear only a small fraction of his output, that's the fault not of his work but of higher priorities calling on my time. He's a controversial figure, but whatever you think of him, the man can write. And speak. And interview the most interesting people.

This obituary is remarkable as much for what it doesn't say as for what it does. Not knowing any of the people involved, I can't attest to the accuracy of Tucker's depiction of his father, but his spare brush strokes paint a vivid picture of a man who accepted the many slings and arrows of outrageous fortune and yet lived his life in duty and delight.

Obituary for my father.

Richard Warner Carlson died at 84 on March 24, 2025 at home in Boca Grande, Florida after six weeks of illness. He refused all painkillers to the end and left this world with dignity and clarity, holding the hands of his children with his dogs at his feet.

He was born February 10, 1941 at Massachusetts General Hospital to a 15-year-old Swedish-speaking girl and placed in the Home for Little Wanderers in Boston, where he developed rickets from malnutrition. His legs were bent for the rest of his life. After years in foster homes, he was placed with the Carlson family in Norwood, Mass. His adoptive father, a tannery manager, died when he was 12 and he stopped attending school regularly. At 17, he was jailed for car theft, thrown out of high school for the second time, and enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps.

In 1962, in search of adventure, he drove to California. He spent a year as a merchant seaman on the SS Washington Bear, transporting cargo to ports in the Orient, and then became a reporter. Over the next decade, he was a copy boy at the LA Times, a wire service reporter for UPI and an investigative reporter and anchor for ABC News, covering the upheaval of the period. He knew virtually every compelling figure of the time, including Jim Jones, Patty Hearst, Eric Hoffer, Jerry Garcia, as well as Mafia leaders and members of the Manson Family. In 1965, he was badly injured reporting from the Watts riots in Los Angeles.

By 1975, he was married with two small boys, when his wife departed for Europe and didn’t return. He threw himself into raising his boys, whom he often brought with him on reporting trips. At home, he educated them during three-hour dinners on topics that ranged from the French Revolution to Bolshevik Russia, PG Wodehouse, the history of the American Indian and, always, the eternal and unchanging nature of people. He was a free thinker and a compulsive book reader, including at red lights. He left a library of thousands of books, most dog-eared and filled with marginalia. His reading and life experiences convinced him that God is real. He had an outlaw spirit tempered by decency.

In 1979, he married the love of his life, Patricia Swanson. They were together for 44 years, all of them happy. She died sixteen months before he did and he mourned her every day.

In 1985, he moved to Washington to work for the Reagan Administration. He spent five years as the director of the Voice of America, and then moved to the Seychelles as the US ambassador. In 1992, he became the CEO of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and later ran a division of King World television.

The last 25 years of his life were spent in work whose details were never completely clear to his family, but that was clearly interesting. He worked in dozens of countries and breakaway republics around the world, and was involved in countless intrigues. He knew a number of colorful national leaders, including Rafic Hariri of Lebanon, Aslan Abashidze of Adjara, Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire, and whomever runs Somaliland. He was a fundamentally nonjudgmental person who was impossible to shock, and he described them all with amused affection.

He spoke to his sons every day and had lunch with them once a week for thirty years at the Metropolitan Club in Washington, always prefaced by a dice game. Throughout his life he fervently loved dogs.

Richard W. Carlson is survived by his sons, Tucker and Buckley, his beloved daughter-in-law Susie, and five grandchildren. He was the toughest human being anyone in his family ever knew, and also the kindest and most loyal. RIP.

Recently I received a notification from Ancestry.com offering me the opportunity to opt out of Mother's Day and/or Father's Day e-mails, in case they might cause me pain.

Dear Ancestry.com,

I appreciate the good intentions behind your desire not to add to any pain I might be feeling about those days into which our culture has chosen to distill the Fifth Commandment to a particular moment in time. I also understand that in so doing you are just following the crowd of companies that have decided it might be good business to show a little apparent sensitivity, as I wrote about last year in the case of Shutterfly.com.

But Ancestry, WHAT WERE YOU THINKING? Honoring our mothers and fathers, and their mothers and fathers, and their mothers and fathers, is the whole reason for your existence.

The study of genealogy is "Honor thy father and thy mother" writ large. And Mother's Day and Father's Day are two of the most inclusive holidays possible. Everyone has a mother, and everyone has a father. That's basic biology, the facts of life. It doesn't say anything about how good a particular father or mother might have been, and neither, for that mother, does the Fifth Commandment.

A company whose core purpose is to connect people with their ancestors should know better than anyone that we research, discover, and honor our forebears not because they were particularly good, or bad—and everyone has plenty of both in his family tree—but because they are ours, and without them we would have no existence at all.

I think that's worth celebrating. If you don't, that's none of my business. But Ancestry.com certainly gets plenty of my business, because of its core purpose and resources—so I find its jumping on the current bandwagon of corporate conscience amusingly ironic.

You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father who is in heaven; for he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust. — Matthew 5:43-45

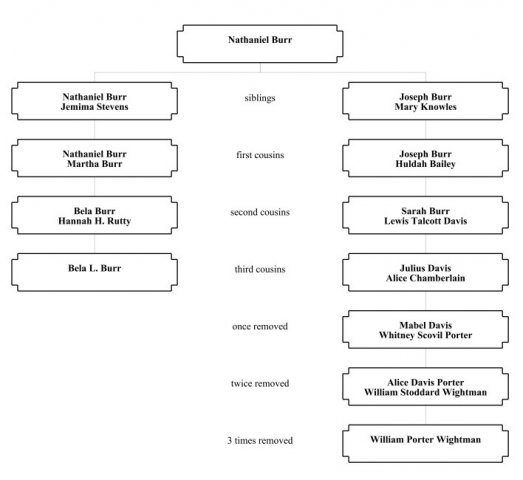

The following inspirational story came to me from one of my genealogy sites, Fold3. An Act of Kindness Unites Enemies is a heartwarming story from the bloody Civil War Battle of Antietam; it especially caught my eye because one of the protagonists is Bela Burr, who happens to be Porter's third cousin three times removed. (Click on any image to enlarge it.)

In case you for some reason can't see the article, here's an introduction, followed by the story as printed in the Harrisburg Telegraph of September 5, 1895. Note that both young men were not yet out of their teens.

The dead and wounded were strewn across the battlefield. Among them was 18-year-old Bela L. Burr. Burr lay in the sun for hours, his wounded leg bleeding. He’d only been in the Union Army one month, having enlisted in the 16th Connecticut Infantry on August 7, 1862. Burr realized his life was slipping away and began resigning himself to the inevitable.

Just then, an angel arrived. But this angel came in the form of a Confederate soldier. James M. Norton, 19, a Confederate picket from Oglethorpe County, Georgia, was marching near the battlefield when he heard Burr’s cries for water. Norton took note of the sharpshooters concealed in the trees. They were aiming at anyone moving on the cornfield. Dropping to his knees, Norton inched towards Burr as shots rang out. He finally reached him and offered him his canteen.

This post has been sitting around for a while, waiting for an opportune time to be published. Given the recent news about 23andMe's decision to go Chapter 11 on us and seek someone to buy the company, now seems as good a time as any.

I'm inclined not to join the delete-my-data panic. It's concerning, but Ancestry.com changed hands back in 2020 without such fanfare. I'm not convinced that deleting our data is going to help anything. But it's worth being aware of.

In the meantime....

23andMe has updated my ancestry composition analysis. AncestryDNA does that periodically, but this is the first from 23andMe in a while—and it includes a surprise.

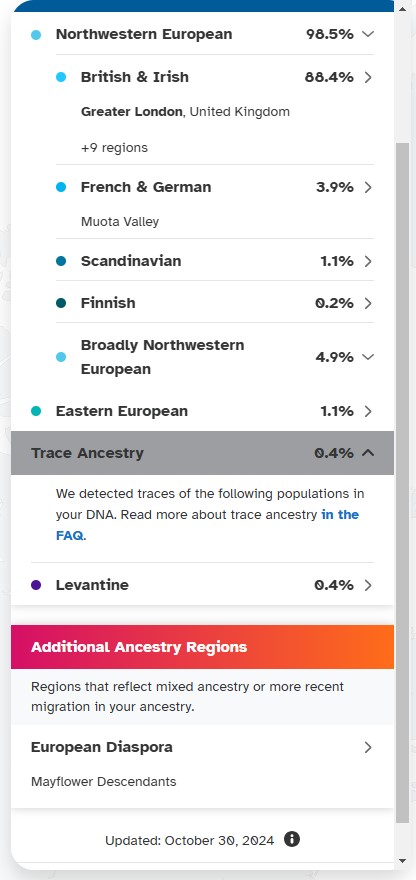

You have to take DNA ancestry results with a bit of a grain of salt, as is evident when you see the results change with each update. As more data become available, as the algorithms are refined, as the population areas are adjusted, the analysis changes somewhat. I'm okay with that; I never take what they tell me as gospel-accurate. Results also differ between services, as they each have their own data and their own algorithms to analyze that data. That said, the general pattern of my results remains the same: I'm about as Northern European as you can get, and most of that is from England and northern Ireland/southern Scotland. Here's 23andMe's latest estimate:

There are actually two surprises

According to their estimates, I actually have a stronger connection to the category, "Mayflower Descendants" than Porter does—and he has one proven Mayflower line and two more that are highly likely. I know of only one probable line for myself, and that is most difficult to prove. (Advancement in genetic genealogy seems to be my best hope for that. Mid-state New Yorkers were not nearly as good at keeping records as the New Englanders were.) Given that there are now some 35 million descendants of the Mayflower passengers, I don't give much credence to my supposed stronger connection.

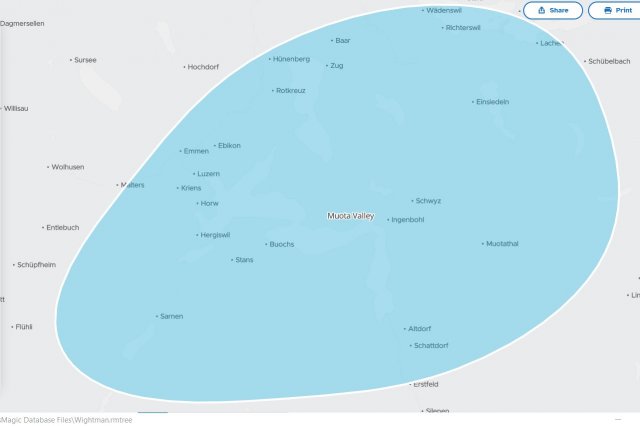

The second surprise is hidden under the category "French & German—Muota Valley." For the first time, the results show significant numbers from that region; what's more, this is the Muota Valley! (Click to enlarge.)

In my research, I had seen hints of some Swiss ancestry on my mother's side, but nothing that I can prove, so finding a connection to the place where our overseas family now resides was cool. As I said, you have to hold genealogical DNA results somewhat lightly—but I'll happily embrace the fun stuff when I can!

Was it a dream or a nightmare?

Both, I think. It was frightening, but it also ended before I wanted it to.

Elon Musk had come to audit my genealogical work.

It was a nightmare, because my research has been sorely neglected for years, and my records are in terrible shape.

On the other hand, he showed me patterns I had not seen, and had ideas I hadn't thought of. I was making progress! Alas, as with most dreams, everything useful fled upon awakening—except the all-important inspiration to get back to work.

If Elon Musk and DOGE will never scrutinize my genealogical efforts, the heirs of my research and my records will, and when the time of their judgement comes, it will be too late for me to get my work in order.

I'm terrible about organizing and identifying photos and memorabilia. My intentions are good, but follow-through abysmal. I keep working on it, but the rate at which objects join the queue far exceeds the rate at which they are processed. I'm so grateful for (1) location stamps on my pictures—whatever the risks are of letting Google know where I am, the benefits for photo identification are immeasurable. And (2) Google Lens and Image Search. The unidentified photo of me as a little girl standing next to some monument? My father wasn't much better than me at keeping up with the documentation, but Google told me immediately that I was on top of Mt. Greylock in Massachusetts! Still, it's a very long and sometimes tedious job, and I just keep putting one foot in front of the other. My goal is to collate photos, memorabilia, and writings into a compact collection that people (i.e. family members) will enjoy looking at. The state it's all in now, if it falls into the hands of my executors, most of it will get tossed. If it's a hard job for me, it will be impossible for them. And I'm not getting any younger.

No pressure.

First, there's all my immediate family's stuff, which has been accumulating since we got married nearly 50 years ago. A couple of dozen large photo books with the pictures in chronological order (good) but largely unlabelled (terrible). Boxes of memorabilia that will be invaluable for identifying photos and for piecing together stories, even if most will eventually be tossed (before or after scanning). Carousels and boxes of old slides, which was the film medium of choice in our earlier days. Eighty thousand digital photos to sift through, label, and organize. The older photos take longer to process, as they need to be digitized and identification is much more difficult. The early digital photos don't need to be scanned, but they include very little identifying information. The pictures we took after getting our smart phones in 2014 are much easier to process because of included date and location data, but make up for that in sheer volume.

That's imposing enough. But as a firstborn (and thus more likely to be able to make identifications of older people and places), and even more as the resident genealogist (who cares the most about family history), I have become the repository for over 100 years worth of old photos (mostly unidentified) and memorabilia, from both my side of the family and my husband's. It has been accumulating in my closet for decades. And I mean accumulating; boxes and boxes that looked good because they were neatly stacked, but inside, all was chaos. I've been ignoring them because other projects have had higher priority, and—let's be honest—because I've been too intimidated to begin.

Recently, however, I girded my loins and pulled the first box out of the closet. I had decided that if I would just get everything roughly sorted by family and era, it would be easier to tackle the smaller chunks (certainly a relative term) piecemeal. That's the theory, anyway.

I began by going through all the boxes and sorting the contents into very rough piles.

It gets worse. What you see here doesn't begin to reveal why I suddenly felt completely overwhelmed when I ought to have been rejoicing in having made a start.

In addition to a lot of stuff that I know I'm going to discard, I found treasure. In particular, a large stack of notebooks containing further journals kept by my father, of which I had been unaware. I had already scanned and organized the 15 journals that I knew about, and that was quite a project in itself. It was thrilling to find more, from the later years; not so thrilling that they were written in unorganized spiral notebooks—here a little, there a little—sometimes in the kind of pen that bleeds over onto the other side.

Plus I found stacks of Dad's letters to the family and essays (with photos) of the many Elderhostel programs he had enjoyed. Dad was a prolific writer and a good one, and it's amazing to read what he wrote about life during our childhood years. I know better than to think I will be able to read them all as carefully as I would like. But I really want to scan them, and do some minimal image editing to make the faded text more legible, so that they will be available, especially to my younger siblings, whose activities they cover more than my own. My first thought had been to toss the Elderhostel writings, but it turns out they make interesting reading, and I think are worth preserving. Maybe that's the writer in me, reluctant to let go of any good writing, or the dutiful daughter who finds value in her father's thoughts. But at least one person in the family has expressed an interest in reading the stories—if they were in an organized form. And most of his letters are worth preserving, being another source of family history.

At one point I hoped to transcribe the journals and letters—and I have my own hand-written journals in addition to his. Why? For the same reason I like to have e-book versions of books (as well as physical copies of my favorites): The ability to search the text. (How old was my brother when he had the chicken pox?) Plus, in the case of handwritten originals, a transcribed version would be much easier and more pleasant to read. My father's handwriting is even harder to decipher than my own, if only because I generally wrote in manuscript, and he in cursive. However, I gave up the transcription dream for two reasons: (1) I'm not planning to live to 150, and (2) I have hopes that Artificial Intelligence, whatever disasters it might bring, will soon be able to do a much better job than the transcription software currently available. So I content myself with digitizing the pages, and occasionally including keywords in the filenames.

This is a huge project (and perhaps a just penance for not keeping my own archivist work up-to-date over the years!) but at least I know that my siblings and children, having entrusted the job to me, are of necessity all on board with my throwing away whatever I can't justify keeping. But that's a big responsibility, too, and one I find particularly difficult. Throwing out items that I figure I may someday want l is not my strong suit. What keeps me going is knowing that it all will be lost if I don't get it into a manageable state.

I took on the job because I care about family history—and possibly because I'm the eldest. First-born's burden, I suppose.

One. Step. At. A. Time.

Hope Serena Daley

Born Friday, May 31, 2024, 6:50 p.m.

Weight: 9 pounds, 11 ounces

Length: 22 inches

Hope was born at home, 17 minutes after the family's midwife arrived. Her timing was amazing; she made her appearance at the exact time her oldest brothers had planned to leave for their orchestra concert. Needless to say, they hung around a little longer. But they made it in good time, and it was an excellent concert—we watched the livestream. Too bad the audience was slightly reduced, but Hope can be forgiven for stealing the show at home.

Grace, the proud big sister.

Twenty-three hours later: Hope and Joy.

I've lost much of my faith in the New York Times, the motto of which seems to have evolved from "All the news that's fit to print" (first generations) to "All the news that fits, we print" (my generation) to "All the news we think you're fit to hear" (now). Still, I think they might have gotten something right in this recent article: Morning Person? You Might Have Neanderthal Genes to Thank. If you find that behind a pay wall, here's the relevant part:

Neanderthals were morning people, a new study suggests. And some humans today who like getting up early might credit genes they inherited from their Neanderthal ancestors. The new study compared DNA in living humans with genetic material retrieved from Neanderthal fossils. It turns out that Neanderthals carried some of the same clock-related genetic variants as do people who report being early risers.

I'm not surprised. Supposedly, I have more Neanderthal genes than 91% of all those who have been tested by the popular 23andMe system. And I'm definitely a morning person. I generally wake up naturally between 4:00 and 5:30 a.m. bright-eyed-and-bushy-tailed. "Sleeping in" means sleeping till 7; that's rare, and generally doesn't happen unless I'm sick ir out of town. I'm not sure why the latter changes my sleep patterns; I'm sure it's part the change in daylight hours, and in part that my routines have been interrupted. In any case, I do my best work in the morning, and unless I'm hot-and-heavy into some interesting work, I'm pretty much useless after 9 p.m.

The odd thing is that I didn't discover my morning-personhood until later in life. Clearly environment has a strong effect. My parents were much more night owls than I am, routinely staying up past 11 p.m., which influenced my own bedtime. And a life ruled by prime-time TV hours (8 p.m. to 11 p.m.) and morning alarm clocks (school or jobs) is automatically a life of disrupted circadian rhythms.

It was our children who introduced me to the joys of the early morning hours. I didn't realize it so much at the time, as they also introduced me to the phenomenon of chronic sleep deprivation. I was getting up early, but also staying up late. As every parent knows, when you have children, that slice of time we like to call "our own" diminishes drastically. Our kids may have been in bed by eight o'clock, but I habitually stayed up until 11 simply because it was the only time I could do any kind of concentrated work. Not that you could call it quality time for the way my brain works, but I tried.

Thank you, dear Neanderthal ancestors, for giving me the genes to enjoy God's beautiful mornings. It's great to finally be in a position where I can take advantage of them. I could insert here a rant against Daylight Saving Time here, but you already know how I feel about that!

Here's a PBS story with information on how Neanderthal (and Denisovan) genes live on in modern humans. I'm taking it personally; after all, 23andMe tells me that I have more Neanderthal genes than 91% of their customers: Out of the 7,462 variants we tested, we found 279 variants in your DNA that trace back to the Neanderthals. Granted, my Neanderthal ancestry adds up to less than 2% of my DNA, but it's still more than most people have.

So if you think some of my ideas are old-fashioned, even Stone Age, at least I come by them honestly.

The bad news:

In 2020, research by Zeberg and Paabo found that a major genetic risk factor for severe COVID-19 is inherited from Neanderthals. “We compared it to the Neanderthal genome and it was a perfect match,” Zeberg said. “I kind of fell off my chair.”

The good news:

The next year, they found a set of DNA variants along a single chromosome inherited from Neanderthals had the opposite effect: protecting people from severe COVID.

The science behind the news (links in the quotes) is more than I want to think about, and I have no idea how the protective vs. risk factor genes work out in my case. After all, I may have more Neanderthal genes than most, but that's still only a small fraction, and I don't even know if the variants involved are among those tested by 23andMe. So I'll just go back to making my Covid decisions based on other factors.

And smiling when someone suggests my views are out-of-date.

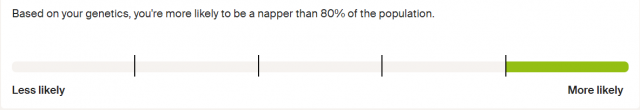

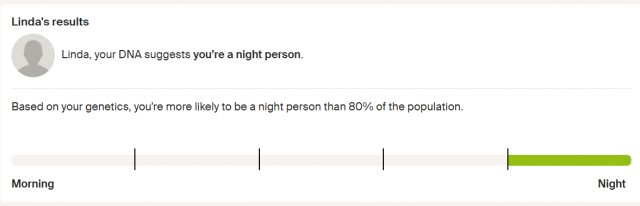

Ancestry was totally wrong about my feelings toward cilantro—they say I'm prone to disliking the herb, but I love it—but they nailed this one.

On the other hand, they are 180% out of phase in calling me a night person. Ideally, I'd sleep from 9:30 to 5:00.

So? About as reliable as a horoscope or a gypsy fortune teller?

Maybe, though overall I've found them more reliable than not; it's the areas of disagreement that stand out.

It's a statistical thing, with all the insights and dead-ends statistical analysis can give you. There's a huge database of DNA out there, albeit currently biased towards those of European ancestry (because the sample is self-selected). If we have given permission (another form of self-selection), companies like Ancestry and 23andMe make their anonymized data available for scientific research. They are careful to make the point that what they provide is not itself scientific research, but gives scientists data from which to form hypotheses and choose a direction and an approach for their research. For example, the data indicate that people with blood type A are more likely to have problems with COVID-19 than people with blood type O. (I may have the details wrong here, but you'll get the idea.) In itself, that proves nothing, but has inspired research into why it might be, in hopes of learning more about the disease and its treatment.

Statistically, most people in Ancestry's database with a bunch of the same genetic markers I have are night people, like to take naps, and hate cilantro. All statistical analysis reveals outliers. For my love of cilantro and the morning hours, I am one; for naps, I am not. Ancestry and 23andMe are careful to point out that our DNA is not a fixed destiny; how our genes are expressed can be affected by how we live.

More fascinating yet, Sharon Moalem's book Inheritance: How Our Genes Change Our Lives—and Our Lives Change Our Genes (thanks, Sarah!) reveals that how we live can even impact how we express our genetic inheritance to our children.

There I was, pondering what I might say in today's blog post, when my sister-in-law sent me the following article, from People magazine: "Connecticut 'Witches' Could Be Exonerated 375 Years After Going on Trial." Connecticut Representative Jane Garibay apparently has nothing more important or interesting to do than tilt at windmills.

Local historians and descendants of the Connecticut witches and their accusers hope lawmakers will finally deliver them all a posthumous exoneration. "They're talking about how this has followed their families from generation to generation and that they would love for someone just to say, 'Hey, this was wrong,'" Rep. Jane Garibay told AP. "And to me, that's an easy thing to do if it gives people peace."

Really? The world truly has gone nuts. I'm happy about our family's connection with these women (and the rare man). They hardly need exoneration, especially not from someone who couldn't tell a witch from a warlock.

Instead of accomplishing the work I had intended to do this afternoon, I did a little digging. Here are the people I've found so far among our ancestors who were accused of witchcraft:

My side:

- Mary Perkins, wife of Thomas Bradbury, accused and convicted in Salisbury, Massachusetts but escaped hanging, for reasons unknown. She is my 9th great-grandmother through my father's Bradbury line.

- Winifred King, wife of Joseph Benham, accused three times in New Haven, Connecticut. The first two times, the charge was dropped; the third time she fled to New York. She is my 8th great-grandmother through my father's Langdon line.

My husband's side:

- Mary ----, wife of Thomas Barnes, convicted in Hartford, Connecticut and hanged. She is his 8th great-grandmother through his mother's Scovil line.

Both sides, though not a direct ancestor:

- Mary Bliss, wife of Joseph Parsons, charged but acquitted. She is my 9th great-grandaunt through my mother's Smith line, and also my husband's 9th great-grandaunt through his mother's Davis line.

You'll note that I have not found anyone accused of witchcraft in my husband's father's line, though it is brimming with early New England ancestors. But that's okay, because it is through him that my husband is related to his 9th great-grandfather, Edward Wightman, the last person to be burned at the stake in England for heresy. Edward is also my own 10th great-grandfather, through my father's Langdon line.

Unlike New England's witches, Edward, it seems, was guilty as charged, and more than a little bizarre by the end. But to be a genealogist is to realize that we come from heroes and villains, the oppressed and the oppressor, the innocent and the guilty—and to embrace them all as our own.

To be real you need to celebrate your own history, humble and tormented as it might be, and the history of your own parents and grandparents, howsoever that history be marked by scars and mistakes. It is the only history you will ever have; reject it and you reject yourself.

— John Taylor Gatto

It started innocently enough, with an e-mail from AncestryDNA informing me of an additional trait revealed by my genetic makeup: my inclination to seek out or to avoid risky behavior. I could have predicted the result: I definitely prefer to avoid risk. Except, of course, that if I were as risk-averse as they say I am, I wouldn't be about to write something that could get me cancelled by Facebook.

The trigger was in one of Ancestry's explanatory paragraphs:

The world around you also affects your appetite for risk. Younger people and folks who were assigned male at birth report taking the most risks, which may be influenced by environmental factors like social rewards. Some influences are closer to home, like whether your parents encouraged risk taking. Also, our popular understandings of risk may skew more toward physical and financial risks than emotional ones. It's not only risky to do things like step onto a tightrope blindfolded. It's also risky to be honest about your feelings, admit ignorance, and express disagreement. In other words, it's risky to be yourself.

Really, Ancestry? Folks who were assigned male at birth? You mean men? If there's one place I'd expect to be free from this massacre of language, not to mention of reality, it would be a company that makes its money telling people about their chromosomes. When the attendants at my birth announced, "It's a girl!" they were not assigning my sex, they were revealing it, and AncestryDNA should know that better than anybody. Is there any point in trusting the other things they say about my genetics if they think that whether I was born with XX or XY chromosomes is something that was chosen by the birth attendants? Maybe the doctor determined my skin color, too? And the nurse decided I would be right-handed? Humbug.

When American women began coloring their hair, the object was to appear natural (no purple!). Clairol's popular commercial advertising their product contained the catchphrase, "Only her hairdresser knows for sure." My ophthalmologist amended that to, "... and her eye doctor."

While examining my eyes, he had casually announced, "You're actually a blonde." My hair, at that time, was brown, with a smattering of grey. All natural, I might add. A towhead as a child, I had gradually morphed into a brunette. Or so I thought.

"How do you know that?" I questioned.

"You have a blonde fundus. You can dye your hair and fool most people, but your eyes know the truth."

In church yesterday, as in many places across the land, veterans in our congregation were asked to stand and be honored.

I'm fine with that—veterans should be honored every day.

But here's something to remind us that Memorial Day is for honoring those military heroes who cannot stand up because they are lying in graves all over the world, having given "the last full measure of devotion."

Here, today, I once again especially remember Porter's granduncles, who each served, fought, and died in France during World War I, as part of the U. S. Army's 101st Machine Gun Battalion.

Harry Gilbert Faulk, of Old Saybrook, Connecticut, son of Olaf Frederick and Hilma Reuterberg Faulk, wounded in action near Chatêau-Thierry, France, July 25, 1918. Died of his wounds later that day.

Hezekiah Scovil Porter, from Higganum, Connecticut, son of Wallace and Florence Wells Porter, killed in action near Chatêau-Thierry, France, July 22, 1918.

.jpeg)