I hope you don't have to be on Facebook to see this very short clip of the challenge Jordan Peterson gave to ChatGPT.

I said, "Write me an essay that's a 13th rule for Beyond Order [one of Peterson's books], written in a style that combines the King James Bible with the Tao Te Ching." That's pretty difficult to pull off.... It wrote it in about three seconds, it's four pages long, and it isn't obvious to me ... that I would be able to tell that I didn't write it.

As the man said, "Hang onto your hats."

Permalink | Read 476 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I know nothing about any of the people or organizations involved in the following video, but the poem hit me hard when I discovered a few months ago. It expresses deeply one part of the groundswell that resulted in the election of President Trump, and seems particularly appropriate in light of President Biden's recent preemptive pardon of Dr. Anthony Fauci.

Permalink | Read 552 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Here I Stand: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I know some mama bears who need to hear this message from yesterday. I don't want to send it to them individually, for a couple of reasons. One, even though I may be convinced that something about a video will resonate with a particular person, I could be wrong, and maybe even offend that person. I'd much rather make something available and let people decide for themselves. Secondly, even in a small audience like mine, I know there is someone who would benefit from it, though I have no idea who. Maybe some papa bears. Maybe some young people who are facing life with courage and joy yet are feeling old before their time. Who knows? So I put it out there. If you're not feeling overwhelmed and overstressed, feel free to skip this wisdom that is both Christian and Cherokee.

It is from the YouTube channel, Appalachia's Homestead with Patara. I've only been following it since Hurricane Helene, when I friend sent me a link to one of Patera's posts about the devastation there. News from Western North Carolina and East Tennessee was spotty at best, and those with already established communications channels (who weren't totally cut off) were a godsend. This quote is from her About section:

How a suburban family left it all behind in order to homeschool & homestead in Appalachia. Learn how to begin homesteading and to learn vital skills such as gardening, food preservation, animal husbandry, homeschooling, genealogy and more! We have chickens, turkeys, geese, quail, ducks, dairy cows, dairy goats, rabbits, 3 Great Pyrenees & the cutest farm cat around! Come along with us on our journey as we follow our Appalachian roots!

The video is 25 minutes long and does well at increased speed. I hope it is meaningful to some of you, but if not, that's okay, just move on.

Permalink | Read 603 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] YouTube Channel Discoveries: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Here I Stand: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Consider this: The election of President Trump may be all that stands between us and nuclear war.

Does that sound crazy to you?

Okay, here's something crazier: President Biden just authorized the Ukraine to attack deep into Russian territory using American missiles.

This, like encouraging the Ukraine to join NATO, crosses another "red line" for Russia. From the BBC article linked above:

In September President Putin warned that if this were allowed to happen, Moscow would view it as the "direct participation" of Nato countries in the Ukraine war.

"This would mean that Nato countries… are fighting with Russia," he continued.

The following month, the Kremlin leader announced imminent changes to the Russian nuclear doctrine, the document setting out the preconditions under which Moscow might decide to use a nuclear weapon.

This was widely interpreted as another less-than-subtle hint to America and Europe not to allow Ukraine to strike Russian territory with long-range missiles.

This is 'way beyond "poking the bear."

It almost makes me believe those who say there are many in our government (with both D's and R's after their names) who want us to go to war with Russia. Who want us to go to war with Iran. Who are actively pushing us into these wars.

That is no garden-variety crazy. That is pathologically insane.

I've said from the beginning of the 2022 escalation of America's involvement in the fight between Russia and the Ukraine that we seem intent on leaving President Putin no way to save face, to back off without being utterly defeated, which strikes me as stupid on any number of fronts. Who in his right mind could possibly want to set off World War III? Seriously. Why do we continue to push Russia into an ever and ever tighter corner? Desperate people—and desperate countries—do desperate things. This is no situation of "we think maybe Iraq has weapons of mass destruction." We know Russia has them, and we should not be leaving nuclear, chemical, and/or biological warfare as their only options.

Even if we could keep a confrontation to conventional warfare, do you think the American military is adequately prepared for such a fight, likely on several fronts? I have no such confidence. Certainly the American public is not ready. Military standards, recruitment, and satisfaction in the ranks are all suffering. If FEMA couldn't find enough generators to help out Appalachia after Hurricane Helene because we gave them to the Ukraine, what about all our military equipment that went that direction? Sure, we can rebuild with newer and better equipment, but That. Takes. Time. Time we may not have. And money we certainly do not have.

Do you really want to bring back conscription? Maybe if you haven't lived through the Vietnam Era you can't understand the devastation that the draft brought to individuals, families, communities, and the entire country. If you think we are broken and divided and hurting now....

"Bodily autonomy" has proved to be a powerful rallying cry on both sides of the aisle, with Democrats using it primarily to mean the right to have an abortion, and Republicans using it primarily to mean the right to not have a COVID shot. Everyone agrees that the government's authority over our bodies and those of our minor children should be extremely limited. Everyone except those who favor conscription, that is.

Even that doesn't matter if the nukes start flying.

I'm praying that President Putin will remember that in a couple of months we'll have a new president, and be restrained in his response. New administrations can often be an excuse, welcomed on both sides, to break impasses—as when the hostages held by Iran for more than a year were finally released as soon as Ronald Reagan took office.

I suppose it's possible that this apparently unhinged action on the part of President Biden is actually a move calcuated to put incoming President Trump in a better negotiating position with the Russians. If so, I'd still call it more crazy than clever. But I'll be praying that it works.

Today, as I repeatedly refresh the map of Milton's predicted path, I've been thinking a lot about Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four.

My standard hurricane prayer is this: Please diminish, disorganize, and disperse this storm, and divert it to where it will do the least harm.

That's what I pray, and in my better moments that's what I mean.

In my not-so-good moments, however, I find my heart cheering whever the predicted path moves away from our home—which means it's moving toward someone else's.

All I can think of is, "Do it to Julia!"

Permalink | Read 575 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

In case you are curious, here's the lastest predicted path (11 a.m.):

Permalink | Read 619 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The public schools around here have already decided to close for tomorrow, and I wonder why.

I take the possibility of a hurricane seriously and tend to err on the cautious side (no hurricane parties); what I question is the timing. So many times in my memory have schools been closed for days that turned out to be absolutely fine. With the weather—especially storms—you simply can't know so far in advance what is going to happen, so why make the decision so early?

I didn't grow up with hurricanes, but we had "snow days," and never knew till the same day whether we'd have school or not. Those are great memories: ears glued to the radio, listening to the list of schools that were closed. It was usually a long list, since most school districts were local and small, and my school district began with an "S" and thus came near the end. Oh, the cheers when they finally called our name (or groans, if they didn't)! My mother cheered as enthusiastically as we did—or so it seemed to me at the time.

The deciding point for closure was whether or not the roads could be plowed in time for the school buses to make their runs. (All but a small handful of us walked to my school, and they never worried about us, but they closed the whole district if the buses to other schools couldn't run. I was grateful for those rural schools.) The Superintendent of Schools would wake up early, assess the situation, and make the decision then.

I don't understand why Florida doesn't do the same.

On the other hand, at least when it turns out to be a false alarm, the kids here have a nice day off. But as I understand it, they must make up missed days later in the year, which we never did, and it sure seems unfair to shorten an expected vacation!

Permalink | Read 752 times | Comments (3)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The following is from CNN. If you want the information from a news outlet with a different political perspective, you can easily find it. It is essentially the same wherever I look, with varying degrees of concern being expressed but the same story.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky told CNN that Ukraine’s request to use long-range missiles on targets inside Russia is part of his “victory plan,” that he is due to present to US officials next week.

Zelensky has been pushing Ukraine’s allies to ease restrictions on weapons and although there have been signs of the US shifting its stance he said they are yet to be given the go-ahead.

“We do have long-range weapons. But let’s just say not the amount we need.” Zelensky said Friday, adding that “neither the US nor the United Kingdom gave us permission to use these weapons on the territory of Russia.”

Speaking to journalists, Zelensky blamed the allies’ hesitation to authorize such use on escalations fears.

Escalation fears? And rightly so! Zelensky wants us to authorize the use of American missiles to strike deep into the sovereign nation of Russia, and he thinks we shouldn't be concerned about how Putin would react?

How would we react if Putin should supply Cubans with missiles and authorize them to use those missiles on the United States? Oh, wait—haven't we seen this already? And avoided World War III by the skin of our teeth and the courage of a Russian Naval officer?

We have been overtly and dramatically poking the Russian bear over the Ukraine for more than two years, including crossing Russia's "red line" by encouraging NATO membership for Ukraine. Actually, we've been messing with Ukraine's politics for a lot longer than that, though most Americans (including me) only became aware of it in early 2022.

Are we so divorced from the natural world that we have forgotten how unwise it is to tease a bear? Let not the one who encourages another to repeatedly provoke a bear think that he himself will escape when the bear turns wrathful.

It is the height of hubris to believe that America can flirt with World War III and remain unscathed. I acknowledge that sometimes a wise, bold, and decisive move made in the right way at the right time can bring about a strategic victory, but that opportunity has passed. It's only my opinion, but for what it's worth, I believe Russia and the Ukraine could have worked out a settlement early on if we had not been encouraging Zelensky and the Ukrainians to believe they could actually win all they want from this war. It's true that a much larger power can sometimes be defeated by persistence on the part of the smaller party and indecisiveness on the part of the more powerful one (e.g. Vietnam and Afghanistan), but the cost—in lives, land, infrastructure, and resources—is unspeakably great. A prolonged war only enriches the wrong pockets.

Consider:

- The United States military is not in a position to win a direct war with Russia, without resorting to terrible—and illegal—weaponry. I'm sorry to say that, and I mean no disrespect to our military personel—at least at the lower levels; I think less of the top brass and the politicians who are making our biggest decisions. But we are insufficient in hardware, personnel, and morale. Our only hope is that Russia is worse off, which it likely is at this point, but that makes it all the more likely that Putin will step out of the bounds of conventional warfare.

- That part about being insufficient in personnel? Perhaps only one who has lived through years of military conscription, as I have, can truly understand the horrors of a draft, the internal damage it causes a nation, and the blessings of an all-volunteer military. I don't see an out-and-out war being fought, let alone won, without a march larger military than we have, and that means conscription. Are we prepared to sacrifice our sons (and likely, this time, our daughters) in a fight that never should have been ours in the first place, if there is any reasonable way it can be avoided?

- We are pouring untold billions of dollars into Ukraine aid, of which over 100 billion directly aids the Ukrainian government. (See this article from the Council on Foreign Relations for details.) Leaving aside all issues of how much is lining corrupt pockets, and how much is sleight of hand in which the U.S. is getting rid of outdated equipment in hopes of being able to replace it with newer technology, that's still an incredible amount of money that we don't actually have. We are saddling our children and grandchildren with an enormous debt burden that makes their impossible college debts look like pocket change. (Side question: Does anyone even have pocket change anymore?)

- Ignoring the critical point that we are spending money that's not ours, and the fact that a massive influx of governmental money often does more harm than good—still, what progress might we have made if we had spend even a small fraction of that (albeit nonexistent) money on (for example) clearing our air and water of dangerous chemicals; supporting childhood cancer research (woefully underfunded compared with other cancers); strengthening our national security by encouraging small farms and businesses, protecting our farmlands and natural resources, building up and protecting our infrastructure, and bringing critical manufacturing back to the United States? (I'm all for international trade, but not at the expense of our independence.)

- By our actions, we have forced Russia to strengthen their ties significantly with countries that view us as a common adversary, China and Iran in particular. That's not good. I'll take a trade war over a war with bombs any day.

- By our heavy involvement in the Ukraine, we have set our relations with the Russian people back decades. They may be upset with Putin for continuing this war, but for certain they are upset with America for what our sanctions have done to them. And rightly so. We had been booked for a visit to Russia in the fall of 2020, and I expected to experience the warm welcome that our friends had enjoyed on their own visits to the country. Thanks to the worldwide, ill-advised panic over the covid virus, that trip was postponed—and later cancelled because of the war. Even if we avoid WWIII, I don't foresee living long enough for relations between Russia and the United States to heal sufficiently for tourist traffic to resume. My father enjoyed his trip to Russia in 1993, when he was my age, and perhaps my grandchildren will have a chance in their later years; I hold no such hope for myself.

- How is it that we care so much about the border between Russia and the Ukraine and so little about the borders of our own country? Our fentanyl and organized crime crises alone are orders of magnitude more important to the American people than which country rules the Donbas.

- I'm starting to believe that the events that mean so much to me, brought home forcefully during our recent trips to Berlin (the Fall of the Berlin Wall) and Gdansk, Poland (the Solidarity Movement), did not please everyone in our country. There appear to be those who very much miss the excitement (and profit) of the Cold War days.

This coming Thursday, President Zelensky will meet with President Biden to push for a green light to send our long-range missiles into Russia.

Regardless of whatever your political opinions may be, if you are a praying person, please pray for this meeting, and for his additional meetings with Kamala Harris and Donald Trump. I am more concerned about the possibility of unthinkable war than I have ever been—and I lived through the duck-and-cover days.

Don't be manipulated. Good advice, but very broad, and hard to follow. This post was inspired by what I have read about "bad actors"—AI bots or paid humans—attempting to sow discontent, anger, and hatred online. The Chinese and the Russians have both been accused of this, with what seems to be pretty convincing evidence, and I fear some of it is also homegrown.

My greatest concern is that Artificial Intelligence is rapidly advancing to the point where we can no longer trust our own eyes and ears, at least where online videos are concerned. It is possible to manipulate images and audio to make it appear that someone is saying something he or she never said. Think what political enemies could do with that! Everything from rigging elections to starting World War III. And you know those crazy spam blackmail threats that claim they recorded you doing "nasty things" in front of your computer? The ones you face with a grim smile and quickly delete because you know you never did whatever it is they claim? Imagine them including a video of you "actually" doing or saying what you did not? What if they show you a candidate for public office in that compromising position? Or your spouse, or your children. What about fake kidnappings? I could go on and on—my imagination is fertile and paranoid.

But that's not where I'm going in this post. AI's not quite there yet, and we have a clear and present danger in the here and now: Angry, profane, and hateful comments posted to articles, videos, and podcasts. Nasty online videos (especially the short form commonly seen on Tik-Tok and Facebook Reels) whose purpose (obvious or subtle) appears to be to stir up negative emotions. And that's just what I see every day; I know there's a lot more out there. It's hard not to have a visceral reaction that does no one any good, least of all ourselves.

And that, I'm afraid, is exactly the purpose of what is being posted. To make us angry; to make us suspicious of each other; to influence our reactions, our actions, our purchases, and our votes.

The best solution I've been able to come up with (and I have no idea how effective it might be, except with me) is this:

- Know your sources. Is this negativity coming from someone you actually know, in person, so that you are aware of the context? Is it from someone you know online only, but have had enough experience with over time to assess his general attitude, reliability, and track record? If not, keep your salt shaker near.

- When in doubt, if the content tempts you to react badly, assume the best: It's a bot or troll whose purpose is to make you angry; or a human tool too desperate for a job to consider its moral implications; or an ordinary human being who has been having a bad day/week/year (doesn't that happen to all of us?). In any case, make an effort not to fall into the trap.

- Avoid sources that usually make you react badly. Unfortunately, I don't think we can afford to avoid seeking information about what is happening in the world. One of the first rules of self-defense is to be aware of your surroundings. But we can be cautious. Even the sources I find most reliable can have nasty trolls in the comment section, so I mostly avoid reading the comments. I'm also trying to wean myself off of the Facebook Reels (mostly ported over from Tik-Tok or Instagram it seems). They can be fun, and funny, and sometimes usefully informative. But they are definitely addictive, and I've noticed that far too many of them are negative, even if humorous, leaving an aftertaste of fear, anger, disgust, and/or suspicion. Not good for the human psyche!

- Consider slowing down? I'm struggling with this one, because of the reality that so much of our information comes in video form these days. Unlike print, in which it is easy to skim for information, to skip over irrelevant sections, and to slow down and reread what is important, and which provides a much better information-to-time-spent ratio, the best one can do with video is to speed it up. I find that almost everything can be gleaned from a video just as well if it's taken in at 1.5x speed, sometimes even 2x. Porter's ears and brain can manage 2x almost all the time. This is a blessing when there is so much worth watching and so little time! However, here's what I'm struggling with: videos watched at high speeds tend to sound over-excited, even angry, when at normal speed they are not. And the human nervous system is designed to react automatically to such stimuli in a way that is probably not good for us if we are not actually in a position to either fight or flee. I don't have a satisfactory answer for this, but I figure it's at least worth being aware of.

- Remember that the people you interact with online are human beings, who work at their jobs, love their families, and want the best for their country, just as you do. Unless they're not, in which case it's even more important not to rise to the bait.

Be aware, be alert, do what is right in your own actions and reactions, and hope for the best. It's healthier for us all.

Permalink | Read 717 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Social Media: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

In the mad scramble to establish whether or not immigrant families are eating people's pets and wild ducks and geese in parks, the obvious answer is being ignored: Of course they are! What world are you living in if you think they can't be?

After the United States retreated ignobly from Southeast Asia, we were flooded with refugees from that part of the world. "Flooded" is a relative word; the numbers I can find vary, but it appears that it was around 125,000 people before we closed our doors except for the purpose of reuniting families. Which, of course, is a trickle compared with the multiple millions of people coming in now, from all over the world.

There were naturally plenty of difficulties settling so many Southeast Asian refugees and integrating them into our communities, but there were some significant differences between then and now that made that process generally successful.

- Sheer numbers, obviously.

- Comparatively speaking, their entrance into this country was well-regulated.

- As refugees were brought here, they were sponsored by families, churches, and other groups that took responsibility for helping individual refugee families find places to stay, gain employment, learn or improve their English, navigate paperwork, and get their children enrolled in schools. In addition to that, the sponsors provided much-needed friendly relationships, often long-lasting, in an alien and frightening environment.

- Their presence in our country was clearly legal, greatly reducing the refugees' vulnerability to enslavement by gangs, pimps, unscrupulous employers, and crooked cops, lawyers, and judges.

- Again, the numbers. Small numbers of immigrants, relative to the population, can be assimilated and integrated into the host society without causing massive disruption. There is a difference between a summer storm and a category 5 hurricane.

What does this have to do with eating cats? Everything. Even with the relatively small, orderly, and successful assimilation of the "boat people" of Southeast Asia, people are human. They have problems. They lose their jobs, drop out of school, fall victim to unscrupulous predators, are tempted by illegal activities, or can't handle their money well. Especially as time goes on and the social safety net is not so focused and robust. And don't forget that while many of the Southeast Asian refugees were middle class workers who spoke English, many were also "country bumpkins" with no knowledge of Western culture. They weren't stupid people, but they were smart in their own culture; being dropped into an American city made them as vulnerable as I would be if I suddenly found myself in the jungles of Laos.

So some of them were hungry, and they did what hungry people do: they used the skills they had to find food. They fished in the rivers, not knowing and not caring that the rivers were polluted. The hungry belly does not concern itself with mercury levels. They discovered that squirrels abound in city parks, and squirrels make good eating—or so I'm told. Here, we rely on our local hawks to keep the squirrel population under control; back then, refugee families took care of that. I am not making this up.

If you flood an unprepared—and maybe unsuspecting—city with a large population of migrants who do not fit into the culture, who may not even speak the language, and who have no responsible sponsors to welcome them, some of them are going to be hungry. And they are going to do what they have to do to get food.

They're going to help themselves to ducks found conveniently living on city ponds. If they're hungry enough, they're going to eat cats without a second thought for whose pets they might be. Maybe they come from a culture that is too poor to imagine keeping pets and treating them like family members.

Of course they're going to eat pets, and whatever else they can find.

It wasn't long ago that I wrote the following:

People who buy extra toilet paper, or cans of soup, or bottles of water for storage rather than immediate consumption are not hoarding, they are wisely preparing for any interruption of the grocery supply chain, be it a hurricane, a pandemic, civil unrest, or some other disruption. As long as they buy their supplies when stocks are plentiful, they are doing no harm; rather, they are encouraging more production, and keeping normal supply mechanisms moving.

Plus, when a crisis comes, and the rest of the world is mobbing the grocery stores for water and toilet paper, those who have done even minor preparation in advance will be at home, not competing with anyone.

It's always fun to come upon someone who not only agrees with what I believe, but says it better and with more authority. Lo and behold, look what I found recently, in Michael Yon's article, First Rule of Famine Club.

Hoarders, speculators, and preppers are different sorts, but they all get blamed as if they are hoarders. Hoarders who buy everything they can get at last minute are a problem.

Preppers actually REDUCE the problem because they are not starving and stressing the supplies, but preppers get blamed as if they are hoarders.

Speculators, as with preppers, often buy far in advance of the problems and actually part of the SOLUTION. They buy when prices are lower and supplies are common. Speculators can be fantastic. When prices skyrocket, speculators find a way to get their supplies to market.

I hadn't thought before about speculators. I'd say their value is great when it comes to thinking and acting in advance, but the practice becomes harmful once the crisis is already on the horizon. Keeping a supply of plywood in your garage and selling it at a modest profit to your neighbors when they have need is a helpful service, but buying half of Home Depot's available stock when a hurricane is nearing the coast is selfish profiteering.

Permalink | Read 639 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Food: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Here I Stand: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

After dealing with the COVID-response-induced shortages and empty shelves, a lot of people mock and shame people who buy more than their immediate need's worth of a commodity, calling them hoarders, or (even more derisively) "Preppers." During a time of crisis and shortage, such an attitude is understandable.

In normal times, it is dead wrong.

People who buy extra toilet paper, or cans of soup, or bottles of water for storage rather than immediate consumption are not hoarding, they are wisely preparing for any interruption of the grocery supply chain, be it a hurricane, a pandemic, civil unrest, or some other disruption. As long as they buy their supplies when stocks are plentiful, they are doing no harm; rather, they are encouraging more production, and keeping normal supply mechanisms moving.

Plus, when a crisis comes, and the rest of the world is mobbing the grocery stores for water and toilet paper, those who have done even minor preparation in advance will be at home, not competing with anyone.

Here's an interesting interview with a guy who has studied crisis preparation for decades. I don't know him, don't know anything about him—but he's no fearmonger, despite taking the necessity of the job very seriously. He's calm, and reasonable, and worth listening to, if you have a spare hour.

Listening to this makes me miss the days when we lived in the Northeast, and had a cool basement. That would be a great place to store emergency supplies. Here, we'd have to store everything in our adequate but limited living area: we have no basement, and the garage, the attic, and anything outside are 'way too hot for most of the year (not to mention favorite places for critters to hang out).

On the other hand, we don't have to worry about freezing to death in winter weather. It's been a long time since we've routinely kept a stack of firewood!

Permalink | Read 715 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Food: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Here I Stand: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The first video is from Task & Purpose, and presents a brief history of tiny El Salvador, the progress that has been made against the powerful gangs that have held the country hostage, and at what cost that progress has come. Insights into how previous political mistakes can turn around and bite you, especially if you insist on compounding them with present political mistakes. Plus the question: How much liberty are we prepared to give up in the name of safety? We surrendered much in the face of COVID, which for most of us was a very mild threat. What would we do if threatened by violent, merciless, implacable gang rule?

Think about that next time you watch the world pouring over the Texas-Mexico border and spreading throughout the country. (21 minutes)

For over 60 years our educational system has been fixated on our ignorance of math and science. (Not that we've done much to ameliorate the problem, but at least we pretend to try.) For much of my life I was on board with that, being a fan of the hard sciences, with little respect for social sciences and humanities. The older I get, however, the more I realize that our greatest educational lack, the deficit far more likely to make our lives miserable or even kill us, is in history and current events. That which hath been is now; and that which is to be hath already been. "It can't happen here" (or now, or in my family/town/nation) is a critically dangerous attitude.

Bret Weinstein, who himself lived for a while in Panama, visited the infamous Darien Gap, a gauntlet that kills many and maims most of the migrant families as they fight their way to the Mexico/U.S. border. In the process, he discovers evidence of not one, but two migrations: a migration driven by the pursuit of greater economic opportunities in the United States, which includes people from all over the world, and a lot of families; and a second, cryptic migration which includes mostly people from China, of military age, heavily skewed towards men. Bret and Heather discuss his visit, and his resulting hypotheses about our border crisis, on DarkHorse Podcast #210. I have not actually made time yet to see that podcast, which is an hour and three-quarters long, but here's Tucker Carlson's interview with Bret, which covers the story very effectively. It's an hour long itself, but worth every minute, if you can fit it into the interstices of your day. Or get hooked, as I did, and watch, transfixed, from beginning to end. I prefer to hear the normal pace of the interview, but it also works well at higher speeds.

And neither of these videos considers how much the Mexican drug lords would love to spread their control throughout the United States.

As my daughter said recently: We all have our own kind of hard. Her attention at the moment is on holding her family together while their two-year-old daughter fights for her life against a rare form of leukemia. And it is meet and right so to do.

We all have our own kind of hard, and most of us are overwhelmed.

How can I help our granddaughter and her family in the struggle for her life? In small ways of encouragement, and especially by prayer.

How can I help in the struggle to make the world a good place for her to live that life? I can pray, and I can vote, two of the most powerful actions. I can also keep my eyes open, learn, think, and write, in my very small corner of the Internet.

If [a watchman] sees the sword coming upon the land and blows the trumpet and warns the people, then if any one who hears the sound of the trumpet does not take warning, and the sword comes and takes him away, his blood shall be upon his own head. He heard the sound of the trumpet, and did not take warning; his blood shall be upon himself. But if he had taken warning, he would have saved his life. But if the watchman sees the sword coming and does not blow the trumpet, so that the people are not warned, and the sword comes, and takes any one of them, that man is taken away in his iniquity, but his blood I will require at the watchman’s hand. (Ezekiel 33:3-6)

No one, not even those who do not already feel overwhelmed with critical duties, can keep up with all the sources of danger, but it behooves us to find and listen to those who do the watchman's work. I am not a watchman, but I am a watcher of the watchmen, and what I learn I like to share here. What others take from my writings is not my responsibility; but woe to me if I see a sword coming and don't blow my little trumpet.

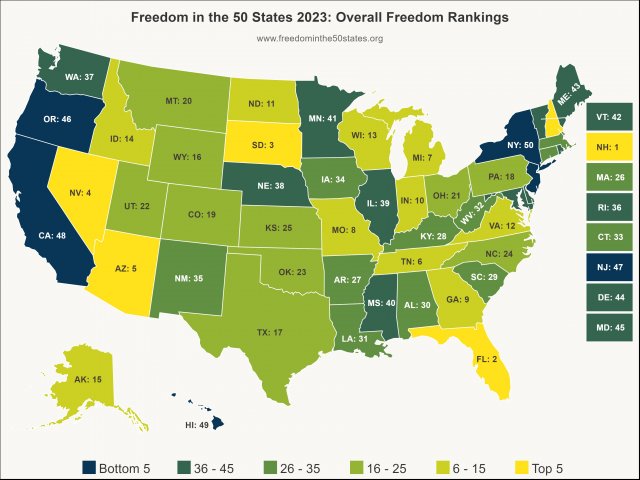

Once again, the CATO Institute has come out with its assessment of relative personal and economic freedom among our states. I'm always suspicious of all those surveys that purport to measure "best state to live in," "happiest city," "most family-friendly country," and such, because so often their criteria are not only different from my own, but even polar opposites. But the CATO Institute appears to have done a good job, and they're open about their criteria and how they calculate their rankings. It goes without saying that there are "freedoms" considered here that each of us would be happy to do without. I'm actually rather pleased that Florida ranks #37 in "gambling freedom," although I understand why that's included in the calculations. They even have an appendix for high-profile issues, such as abortion, that make a generalized assessment of freedom difficult.

Here is the definition of freedom that undergirds this ranking:

We ground our conception of freedom on an individual rights framework. In our view, individuals should be allowed to dispose of their lives, liberties, and property as they see fit, so long as they do not infringe on the rights of others. This understanding of freedom follows from the natural-rights liberal thought of John Locke, Immanuel Kant, and Robert Nozick, but it is also consistent with the rights-generating rule-utilitarianism of Herbert Spencer and others.

Here is an image of the overall freedom rankings. I encourage you to go to the website, however, where you can find much more information.

Way to go, New Hampshire and Florida, the gold and silver winners!

The dubious distinction of coming in dead last goes to my birth state of New York, where I lived until I was 15 and came back again for college and several years thereafter, home of my beloved Adirondack Mountains, and birthplace of our children. I still love New York and pray for it daily, but can no longer imagine—as I once dreamed—of returning to live there. However, your mileage may vary. One man's liberty is another man's license, and New York may be just where you'll feel freest in the areas that matter most to you. (If so, please stay there and enjoy it. Don't move to Florida for the weather or the low taxes and then do your best to make us like New York.)

Freedom of the mind requires not only, or not even especially, the absence of legal constraints but the presence of alternative thoughts. The most successful tyranny is not the one that uses force to assure uniformity but the one that removes the awareness of other possibilities, that makes it seem inconceivable that other ways are viable, that removes the sense that there is an outside.

— Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind

I saw the part in bold quoted online and knew I had to share it here. As usual, my cynical side insisted I confirm that the attribution was correct (so many aren't), so I was able to include a litte more of the text.

One more book for my already impossible need-to-read list.