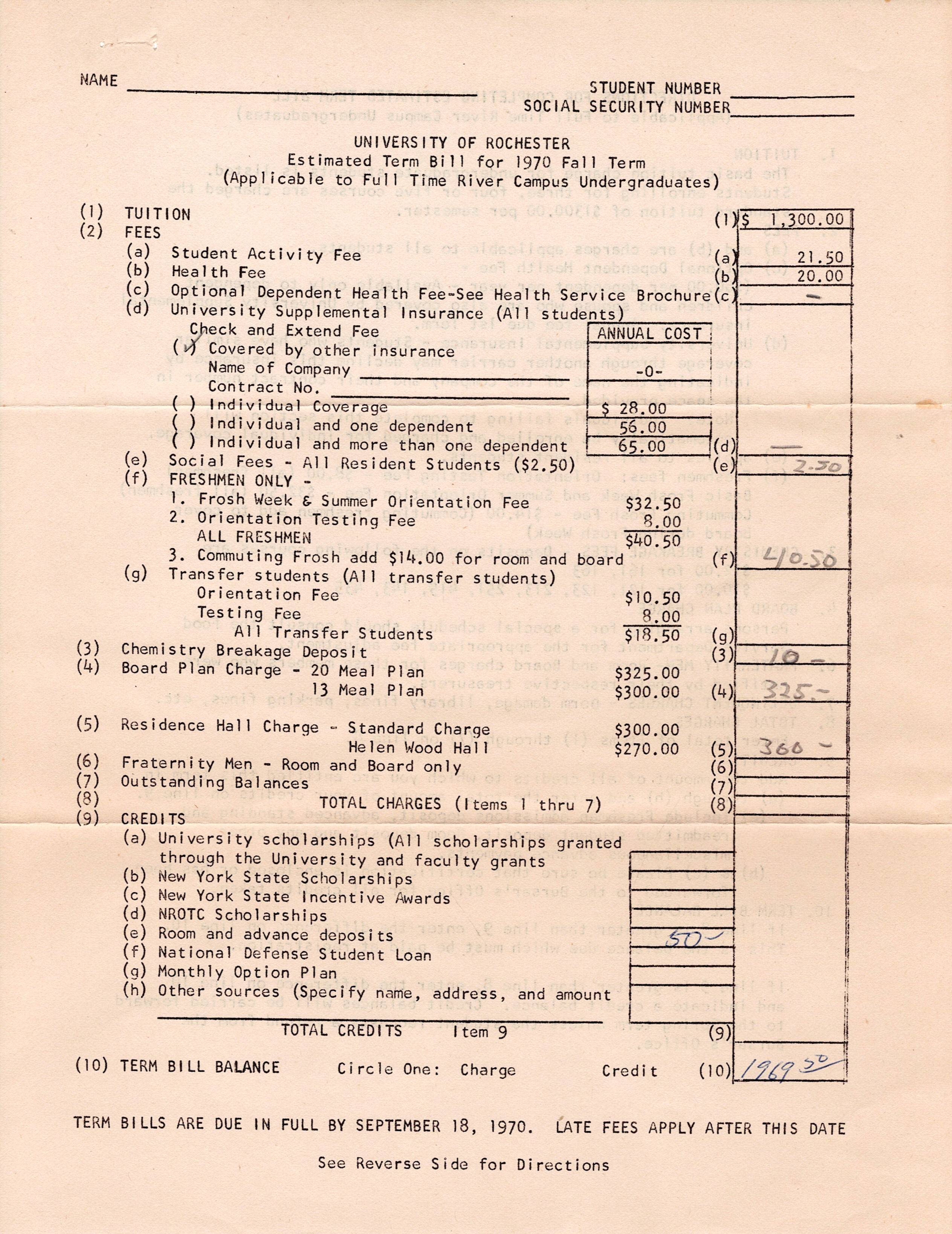

That's the bill for my first semester of college, in 1970. In 2024 dollars, that would be just under $16,000. (Inflation calculators differ, but not by much.)

Let's not look at the total bill, but annual tuition, which is easier to compare.

- Annual tuition at the University of Rochester in 1970: $2600

- Approximate equivalent in 2024 dollars: $21,020

- Current annual tuition at the U of R: $65,870

Why is the inflation-adjusted cost of a college education at my alma mater more than three times what it was when I was there?

- Is the education three times better than it was then? (Highly doubtful.)

- Are the professors being paid three times as much? (Not the ones I know.)

- Are the graduates earning three times the salaries? (A quick investigation indicates the entry-level salaries for a position similar to my first job in 1974 are, adjusted for inflation, very similar to mine back then. But that's far from the whole story. I was in a tech field—computing, the early days—where one could easily expect a salary that justified the cost of college. How many of today's graduates can say the same? Today, far more students are "attending college," but studying what they should have learned in high school, and graduating with degrees that give them little hope of commensurate employment.)

- After four years of college, are today's graduates that much more mature, responsible, capable, well-read, well-rounded, generally competent, and prepared for adulthood—employment, marriage, parenthood, and contributing to society? Are they happier and more well-adjusted than we were? (A small minority are very impressive. But for far too many, college has been a tragic waste of both precious time and an obscene amount of money.)

If the parents in each generation always or often knew what really goes on at their sons’ schools, the history of education would be very different. — C. S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy, 70 years ago

Eventually parents are going to wake up to what a poor job colleges are doing. — a math professor friend, 25 years ago

When is this bubble going to burst? — me, now.

Permalink | Read 579 times | Comments (2)

Category Education: [first] [previous] Glimpses of the Past: [first] [previous]

Whatever you think about Facebook, there's no doubt it can be unintentionally amusing

I mostly find its "Reels" feature to be annoying, and have more than once looked without success for a way to turn it off completely. The short videos it shows are mostly reposted from Tik Tok, which I don't otherwise see. Sometimes they are interesting, sometimes they are genuinely informative and helpful, but all too often I find them infused with a negative view of life, even when they are undeniably—even addictively—entertaining.

Sometimes, however, something unexpected shows up and catches my eye.

If you don't have access to Facebook, you may not be able to watch the video, unfortunately. I spent too much time trying to find a version I could embed here, without success. I hope that link will take you to something you can see, but if not, it doesn't matter.

My readers know that one of our granddaughters plays on her high school girls' soccer team, and that the team has been wonderfully encouraging and supportive of her family during her sister's leukemia journey.

Here's another way they showed their character.

What caught my eye (more accurately, ear) in this video, and made me listen all the way through, was that it's not often when I hear mention of their tiny New Hampshire high school in nationwide media. I think this is the only time I have, actually. So it made me jump.

The short version of the story is that some of the team members did not want to play against a certain other team on their schedule, which included a boy in their lineup. First, in principle, because theirs is a girls' league, not a mixed one, and also because they found the boy physically threatening. The team's coach handled the situation extremely well: those girls who objected to playing that game were excused without any penalty, and the team played the game without any fuss. Somehow it made the news anyway, but I'm proud of the way they handled the situation calmly and fairly.

Our granddaughter? She played the game, with the support of her parents, even though they all thought it unfair for a boy to be on the opposing team. Why? I can't speak for them, but here are a few reasons that came up in our discussion:

- After all she's been through, Faith wanted to support her team, and to play soccer.

- It wasn't the other team's fault that they had a boy on the team—it was a state ruling that forced them to do so.

- Boys and girls often play successfully on the same soccer team—although that's usually at the younger levels, before males gain a significant physical advantage over females.

- They've played against other teams with girls she found more physically threatening than this boy.

The game was played successfully and without incident. I honestly don't remember which team won. In a way, they both did. Don't misunderstand me: The teams should never have been placed in this position, and the state rule that made it happen needs to be fixed.

But bad things happen in this life, and when they are met with quiet grace, that deserves to be celebrated.

Permalink | Read 598 times | Comments (0)

Category Education: [first] [previous] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Pray for Grace: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Here I Stand: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Thanks to the very valuable eReaderIQ, I learned that C. S. Lewis's The Screwtape Letters is currently on sale at Amazon for $0.00. You can't beat that price for excellent content, and it also includes Screwtape Proposes a Toast.

This was a good year for books; not a record, but a very respectable 77 books, 6.42 per month. The fiction/non-fiction ratio was almost exactly the same as last year. No doubt about it: fiction is a lot easier to read when you are at risk of being interrupted. I've been working on RFK Jr.'s The Wuhan Cover-Up for many weeks. It's fascinating, frightening, and frustrating; having read The Real Anthony Fauci two years ago, I'm certain it will also be enlightening, important, and highly accurate. But like that book, it's also so packed with references and documentation that it takes focus to be able to do it justice. The book that is capturing my attention at the moment, Brandon Sanderson's Warbreaker, is not light reading—nearly 600 pages of a complex story filled with unpronouncable names—but there's no denying it's more fun to read.

The stats:

- Total books: 77

- Fiction: 63 (82%)

- Non-fiction: 13 (17%)

- Other: 1 (1%)

- Months with most books: April (10)

- Month with fewest books: July (2)

- Authors read most frequently: Four stood out: Mark Schweizer (15), Jenny Phillips (10), Brandon Sanderson (9), and Robert Heinlein (8). The next highest was three, a position held by several authors.

Here's the list, sorted by title; links are to reviews. The different colors in the titles only reflect whether or not you've followed a hyperlink. The ratings (★) and warnings (☢) are on a scale from 1 to 5, with 1 being the lowest/mildest. Warnings, like the ratings, are highly subjective and reflect context, perceived intended audience, and my own biases. They may be for sexual content, language, violence, worldview, or anything else that I find objectionable. Nor are they completely consistent. For example, Brandon Sanderson's books could easily rate a content warning in all of the above categories, yet they are mostly not inappropriate to the context and could be considered quite mild—for a modern book. Your mileage may vary.

| Title | Author | Category | Rating/Warning | Notes |

| 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos | Jordon B. Peterson | non-fiction | ★★★★ | First read in January |

| 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos | Jordon B. Peterson | non-fiction | ★★★★ | Re-read in July |

| The Abandoned Daughter | Blair Bancroft | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| The Adventures of Robin Hood | Roger Lancelyn Green | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Andries | Hilda van Stockum | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Badger Hills Farm 0: Timothy of the 10th Floor | Jenny Phillips | fiction | ★★★★ | Re-read out loud |

| Badger Hills Farm 1: The Secret Door | Jenny Phillips | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Badger Hills Farm 1: The Secret Door | Jenny Phillips | fiction | ★★★★★ | Re-read out loud |

| Badger Hills Farm 2: The Hidden Room | Jenny Phillips | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Badger Hills Farm 2: The Hidden Room | Jenny Phillips | fiction | ★★★★★ | Re-read out loud |

| Badger Hills Farm 3: Message on the Stamps | Jenny Phillips | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Badger Hills Farm 3: Message on the Stamps | Jenny Phillips | fiction | ★★★★★ | Re-read out loud |

| Badger Hills Farm 4: Oak Tree Mystery | Jenny Phillips | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Badger Hills Farm 5: Clue in the Chimney | Jenny Phillips | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Badger Hills Farm 6: The Hills of Hirzel | Jenny Phillips | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Beowulf the Warrior | Ian Serraillier (retold) | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Between Planets | Robert Heinlein | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| Beyond Order | Jordon B. Peterson | non-fiction | ★★★ | |

| The Bible | non-fiction | ★★★★★ | English Standard Version | |

| The Bible: New Testament | non-fiction | ★★★★★ | King James Version | |

| The Bible: Psalms | non-fiction | ★★★★★ | King James Version | |

| Cavalry Hero: Casimir Pulaski | Dorothy Adams | non-fiction | ★★★★ | Excellent for the history, but a little too much emphasis on the battles and military strategy for my taste |

| Citoyen de la Galaxie | Robert Heinlein | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| The Cottage at Bantry Bay | Hilda van Stockum | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| The Crucible Kingdom | Blair Bancroft | fiction | ★★★ ☢ | |

| Door to the North: A Saga of 14th Century America | Elizabeth Coatsworth | non-fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Eight Flavors: The Untold Story of American Cuisine | Sarah Lohman | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| Fake News Exposed | Daniel R. Street | non-fiction | ★★ | Good ideas, some things I didn't know, lots I already did. Not well written. |

| The Golden Name Day | Jennie D. Lindquist | fiction | ★★★ | |

| The Greatest Salesman in the World | Og Mandingo | fiction | ★★ | |

| I, Robot | Isaac Asimov | fiction | ★★★ | |

| Jack Zulu 1: Jack Zulu and the Waylander's Key | S. D. Smith and J. C. Smith | fiction | ★★★ | Interesting story, weak in places, some very nice spots. Better on second reading. My negative initial reaction was probably due to its being of the school/coming of age genre. |

| Jack Zulu 2: Jack Zulu and the Girl with Golden Wings | S. D. Smith and J. C. Smith | fiction | ★★★ | Good, but of course it ends with a cliffhanger. |

| Karis | Debra Kornfield | non-fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table | Roger Lancelyn Green | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Letters to a Diminished Church | Dorothy Sayers | non-fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Liturgical Mysteries 01: The Alto Wore Tweed | Mark Schweizer | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | |

| Liturgical Mysteries 02: The Baritone Wore Chiffon | Mark Schweizer | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | |

| Liturgical Mysteries 03: The Tenor Wore Tapshoes | Mark Schweizer | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | |

| Liturgical Mysteries 04: The Soprano Wore Falsettos | Mark Schweizer | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | |

| Liturgical Mysteries 05: The Bass Wore Scales | Mark Schweizer | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | |

| Liturgical Mysteries 06: The Mezzo Wore Mink | Mark Schweizer | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | |

| Liturgical Mysteries 07: The Diva Wore Diamonds | Mark Schweizer | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | |

| Liturgical Mysteries 08: The Organist Wore Pumps | Mark Schweizer | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | |

| Liturgical Mysteries 09: The Countertenor Wore Garlic | Mark Schweizer | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | |

| Liturgical Mysteries 10: The Christmas Cantata | Mark Schweizer | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | |

| Liturgical Mysteries 11: The Treble Wore Trouble | Mark Schweizer | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | |

| Liturgical Mysteries 12: The Cantor Wore Crinolines | Mark Schweizer | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | |

| Liturgical Mysteries 13: The Maestro Wore Mohair | Mark Schweizer | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | |

| Liturgical Mysteries 14: The Lyric Wore Lycra | Mark Schweizer | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | |

| Liturgical Mysteries 15: The Choir Director Wore Out | Mark Schweizer | fiction | ★★★ ☢ | |

| The Man Who Sold the Moon | Robert Heinlein | fiction | ★★★ | collection of stories |

| The Many Assassinations of Samir, the Seller of Dreams | Daniel Nayeri | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| Reasons to Vote for Democrats | Michael J. Knowles | other | ★★★ | a largely blank book |

| Mistborn 4: The Alloy of Law | Brandon Sanderson | fiction | ★★★★★ ☢ | |

| Mistborn 5: Shadows of Self | Brandon Sanderson | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | |

| Mistborn 6: The Bands of Mourning | Brandon Sanderson | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | |

| Mistborn 7: The Lost Metal | Brandon Sanderson | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | |

| The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress | Robert Heinlein | fiction | ★★★ ☢ | Heinlein's adult books were never as good as his juveniles, but this story line is better than 1984, and the book is important for the same reasons. |

| Mooses with Bazookas | S. D. Smith | fiction | ★★★ | Interesting but not really my kind of humor |

| Orphans of the Sky | Robert Heinlein | fiction | ★★★ | |

| Percy Jackson and the Olympians 1:The Lightning Thief | Rick Riordan | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| Percy Jackson and the Olympians 2:The Sea of Monsters | Rick Riordan | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| The Rolling Stones | Robert Heinlein | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| The Screwtape Letters | C. S. Lewis | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Screwtape Proposes a Toast | C. S. Lewis | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| The Sea Tiger: The Story of Pedro Menéndez | Frank Kolars | non-fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Skyward 1: Skyward | Brandon Sanderson | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Skyward 2: Starsight | Brandon Sanderson | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Skyward 3: Cytonic | Brandon Sanderson | fiction | ★★★ | |

| Skyward 4: Defiant | Brandon Sanderson | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| The Slight Edge | Jeff Olson | non-fiction | ★★★★ | |

| Space Cadet | Robert Heinlein | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| Space Trilogy 3: That Hideous Strength | C. S. Lewis | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| Time for the Stars | Robert Heinlein | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| Tress of the Emerald Sea | Brandon Sanderson | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| Wimsey Papers | Dorothy Sayers | fiction | ★★★★ |

I love books. I've loved books for longer than I can remember, since my parents read to me long before I could read for myself—as naturally as a bird-parent drops food into its hatchlings' mouths.

The transition from non-reader to reader was not without its stumbles. Even at my advanced age, I still remember Charlotte's Web with both pleasure and pain. My parents had been reading the book out loud to the family. As the oldest child, the one who could now read on my own, I grew impatient with the one-chapter-at-bedtime pace, and the next day picked up the book and continued the story on my own.

Maybe that's not always a bad thing, but it meant that I was alone when I encountered Charlotte's death. If there was some of the deadly sin of Avarice in my action, it carried its own punishment with it. Ah, well—rites of passage are not meant to be easy.

The transition from non-reader to reader is one of the most significant milestones in modern life, one we don't share with our more primitive ancestors. As recently as 1900, more than 10% of the American population was illiterate. Somewhere between 1969 and 1979, that dropped to below 1%. This, of course, takes no account of how well people read, nor the more disturbing trend of can read but don't. But that's not the question that emerged recently, prompting me to write.

(Yes, this is a new post, not one pulled from my storehouse. It was supposed to be a quick and easy post to make. I should have known better.)

The question is whether or not there are other decisive milestones on the literacy journey, once one has mastered reading Of course there are significant steps in the progress of that mastery, a big one being the transition from being able to decipher words to the technique having become so automatic that it is accomplished with no conscious thought at all to the process, only the content. For example, I can read French well enough to enjoy some books, but it's nowhere near an automatic process.

(I think that there's a point still further, when conscious thought creeps back in, but I never made it through Mortimer Adler's How to Read a Book, much less apply his techniques, so I can't say from personal experience.)

What I'm wondering is how significant to the reader has the advent of e-books been. It's not of the order of the act of reading itself, but the Kindle has certainly changed our lives and reading habits. I'm definitely bimodal when it comes to books: There's nothing like the pleasure of reading a physical book, but e-books have distinct advantages as well, such as being able to carry a vast library in a handheld device, and to search the text, and make notes, and highlights, and to copy excerpts via cut-and-paste rather than laborious typing. On the other hand, e-books don't really belong to us; we may like to think so, but they can be taken away from us at any point. So I will read with the physical books, and I will read with the e-books also.

After that long introduction, here's the incident that gave me pause: After reading six Kindle books in a row, I began another in physical form. (Brandon Sanderson's Warbreaker, if you're curious.) I was reading along, and when it came time to turn the page, I unthinkingly swiped my finger across the lower right-hand corner of the book. That's the way I turn the page with my Kindle

Guess what? It didn't work with the physical book, and I was momentarily taken aback. Even more interesting, I still find myself repeating the motion on occasion, and I'm 143 pages into the book.

The human mind can be peculiar, sometimes.

Citoyen de la Galaxie by Robert A. Heinlein (original publication 1957, this French edition 2011)

Citoyen de la Galaxie by Robert A. Heinlein (original publication 1957, this French edition 2011)

Back in August, I quoted a passage from Robert Heinlein's Citizen of the Galaxy. Inspired by this, and a good deal available for the Kindle version, I decided to reread it—in French.

It was a surprisingly delightful experience.

I had three years of mediocre French classes in high school, and have been working very casually, though consistently, with DuoLingo since I was a beta tester for them back in 2012. I have many frustrations with DuoLingo, but this week I discovered that it has actually given me a lot of French vocabulary and a pretty good feel for grammatical structures. I really enjoyed reading Citoyen de la Galaxie.

Naturally I didn't read it as quickly as the English version, but I surprised myself. My goal had been to work my way through ten pages per day. Instead, I was so caught up in the story that I finished it in just about a week.

It must be admitted that I was not a stranger to the story, which helped enormously. I first read Citizen of the Galaxy when I was in elementary school, and I've reread it several times since. How many times I have no idea, but I know that I last read it in 2017—before that, I don't know, except that it was earlier than 2010, when I began keeping track of the books I read. As I read the French, I was astonished to find the words of the English version coming back to me. Between that, the DuoLingo vocabulary, and occasional help from the Kindle French-English dictionary available at a touch, the reading was easy enough to keep me going.

I would not at all expect the same ease with an unfamiliar book. But the experience was exciting, especially since I would often find myself actually thinking in French for a few minutes after a session of reading.

Author S. D. Smith explains that his children's books are good but not safe—and why that's important. Authors like Smith prepare the ground for children to grow into the heroes we will desperately need.

Permalink | Read 606 times | Comments (0)

Category Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Here I Stand: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Heroes: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

One of my favorite Substack people (Heather Heying, Natural Selections) wrote this in her article entitled, "It’s an Upside Down World, and You’re Living In It."

I used to be a Democrat. Two of the things that I did that felt democraty include:

I bought as much of my food as possible at farmer’s markets, and got to know the farmers who grew my food. I bought organic, and avoided GMOs. When given a choice, I bought food that was grown closer to how it had been before humans got involved—cows that had spent their lives grazing outside, coffee grown in the shade on farms with canopy trees, tomatoes and strawberries picked at perfect ripeness, transported as little as possible, eaten fresh and raw.

And I refused pharmaceuticals except when absolutely necessary—the notable exception being vaccines, which I barely questioned until Covid raised my awareness. Over the counter drugs were no better. The rule of thumb in our house was: the longer it’s been on the market, the more likely it is to be safe. Aspirin seemed like a pretty safe bet, as did some antibiotics, in moderation. Everything else? Buyer beware.

I still do these things. My behavior was always informed by an evolutionary understanding of the world, a fundamental preference for solutions that have stood the test of time (e.g. beef over lab-grown meat), and wanting as little corporate product and involvement in my life as possible. Such behavior just doesn’t seem democraty anymore. It seems like the opposite.

In response, I wrote the following.

For decades, I have been saying that the Republicans need to reinvent themselves as the party of human-scale life. Seeing Trump and Kennedy together call to Make America Healthy Again gives me more hope in that direction than I've had in a long time.

Your beautiful, healthy approach to living felt Democrat-y to you, but in my life it has always been embraced by a mixture of folks, from hippies to conservative Christians, who shared a love of what we saw rejected by mainstream society: children and family life; non-medicalized childbirth and homebirth; the critical importance of breastfeeding; independent and home education; the belief that children can be far more competent and responsible than we give them credit for; small businesses; small farms and natural foods; the superior flavor and health benefits of raw milk and juice, pasture-raised animals, and organically-grown fruits and vegetables; homesteading and preserving/restoring the land; reclaiming heritage breeds and seeds; and a deep concern for the environment that was called conservation before it was taken over and ruined by the environmentalist movement.

If the Republican Party will truly embrace and fight for these values, I will in turn be thrilled to have finally become a Republican after 56 years a Democrat. The beginning of the end of my complacency with the Democratic Party was discovering the party's intense opposition to homeschooling—despite the fact that so many of the home education pioneers were radical liberals in their day.

Home education may have been the beginning of my disaffection, but the disconnect between the Democratic Party and the values I thought were their priorities became more and more obvious, accelerating at a most alarming rate, to the point where I agree with Dr. Heying again:

The democrats are claiming that they’re on the side of the little people. The only proper response to such claims is this: No. No you are not. Stop lying. And: No.

Republicans, this is your chance. Don't blow it by infighting, nor by sabotage from within. Reach out to the Independents and disaffected Democrats—like Dr. Heying, and RFK Jr., and Sasha Stone...and me—who are reaching out to you, willing—eager—to put aside our differences long enough to do the really hard work of seeking and saving that which is rapidly being lost.

Permalink | Read 670 times | Comments (0)

Category Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Food: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Conservationist Living: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Here I Stand: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

David Freiheit, who is still "my favorite Canadian lawyer," despite now living in Florida and no longer practicing law, interviewed Sam Sorbo, a woman who had not been on my radar at all, about homeschooling. I said that Sam was not on my radar, but as he introduced her and mentioned her husband, his name rang a bell for me. I had no idea why. I can hear my family laughing at me, because, while my brain can easily cough up trivia like the second lines of famous poems, there seems to be a black hole in my memory when it comes to people associated with popular music and movies. They will be proud of me, however, because it didn't take me (okay, me and Google) long to solve the mystery: Kevin Sorbo was one of the stars (and better actors) of The Firing Squad, the movie that we watched just a couple of weeks ago.

Puzzle solved, I could settle down and enjoy the interview, which I share here. The content starts at 4:47 and goes on nearly to the very end, making it over an hour long. The school stuff starts about 22:00; what comes before is the story of how she got to that point, which I also found interesting. As an old-time homeschooler—20th century, with grandchildren homeschooling in the 21st)—I love hearing today's homeschooling journeys, how things differ, how they are the same, what we've learned, what we've forgotten. Above all, I like to hear the enthusiasm of converts and potential converts. Do this, not because the alternative is so bad (although it often is), but because this is so good!

When our daughter and her family moved to a small town in New Hampshire, the disadvantages were obvious to me. Over time, I've learned to see the advantages as well. Two segments of the following America's Untold Stories video make me all the happier they live where they do, and I want to tell my grandchildren: Hang on to your hometown! But also, be aware of what's happening elsewhere, so you can recognize the beginning stages when they come to you.

Back when our children were still in elementary school, I attended a conference at which a speaker regaled us with horror stories of what was going on in public schools. I'm afraid I didn't take her too seriously, because—like so many people who are passionate about an issue—she came on too strong, and painted a picture far too bleak to resonate with my own experiences. I was very much involved in our local public schools, and had not seen the abuses she was describing. The thing is, she was right. She was ahead of her time, and her stridency put people off—not unlike the Biblical prophets. But all she warned against came to pass, and orders of magnitude worse.

One reason I like America's Untold Stories is that Eric Hunley and Mark Groubert pull no punches without being strident, and more often than not have personal experiences to back up their concerns. Caveat: I haven't listened to the entire show, which is over two hours long at normal speed, so I don't know what else they talk about. The first segment I'm concerned with here, about the "Homeless Hilton" being built in Los Angeles, runs between the 17-minute mark to minute 26; from there until minute 48 deals with the New York City school system.

[Quoting Manhattan school board member Maud Maron] Parents, and the children of immigrants who came from former Communist countries—Eastern Europeans and the Chinese—were saying, "Maud, we know what this is, and this isn't good."

It's easy to think, "Well, that's Los Angeles and New York; it has nothing to do with my town, my city, my schools." To that I can only say, weep for those cities, pray for those cities—and be awake and aware of how your own home might be at risk of starting along the same paths.

The advantages of homeschooling certainly aren't new to me, but I still love to read about people's happy experiences. You can read all of this one for free, though as I recall you may have to give them an e-mail address. (Oh, how I love having our own domain, and being able to create "throw-away" e-mail addresses as desired; it's the e-mail equivalent of using generated credit cards, which I also love.)

This is the story of Nadine Lauffer, now 18 years old, who began her schooling in the Netherlands. Knowing no English when her family moved to Florida, she had to repeat kindergarten, but as with all children who are exposed to new languages that young, that was no problem for her, and she continued in public school until fourth grade. At that point, frustrated by the lack of individual attention in the crowded public school, and impressed by the personalities of the homeschooled children they met at church, her family embarked on their own home education adventure.

“The teenagers,” she said, “were very different from the normal teenagers that I'd met coming from the public school system. They were more attentive, they knew how to talk to adults, and they were joyful.”

Nadine continued to homeschool through high school, going through a difficult period where she struggled with what she might be missing by not being in public school. Until, that is, she investigated and decided that she was actually lucky to have missed out on much of the high school experience. In addition, she began to take responsibility for her own education, which is, after all, the primary goal of homeschooling.

[After hearing a talk by Andrew Pudewa, founder of the Institute for Excellence in Writing], Ms. Lauffer was encouraged to go through her high school experience in a way that fit her and to focus on her love of learning rather than trying to mimic what was going on in public schools.

Nadine's account isn't much different from the experience of millions of other homeschoolers, but in a world gone crazy, we need happy stories, and the reminder that there's still a good number of people in the world who are not insane (even in public schools, though it can be harder there).

An article in today's Orlando Sentinel boasts this headline: Florida students make ‘substantial gains’ on state tests, new results show. I'm not going to say much about this happy headline, except to note that the joy includes the fact that only 22% of third graders failed to read at grade level, down from 27% last year. Other statistics are similarly dismal. This in a state that U.S. News & World Report ranked #1 in education.

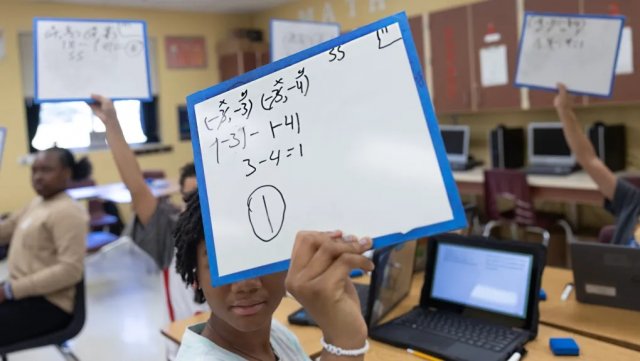

But it's not the schools I'm taking issue with at the moment. It's the newspaper, which with the article ran this photo of middle school students learning math. (Photo credit Willie J. Allen Jr/Orlando Sentinel) (click to enlarge).

As near as I can figure out, the problem is to find the distance between two points on a Cartesian plane, (-3, -3) and (-3, -4). What's written is not the way I would have approached the problem, but—assuming scalar distance, since no direction was specified—the answer is, indeed, 1. I'm also assuming that some of the work was done in the student's head, and these are just notes taken along the way.

Nonetheless, instead of a room full of (possibly) eager math students, what stands out to me—in an article bragging about improvement in math scores—is the equation,

3 - 4 = 1

I can be a sucker for headlines like "Second grade math question has the internet fighting over the answer," and this time I was caught despite knowing it was click-bait. Here's the question:

A mother posted what she said was her child’s second-grade math homework. Here’s how the question goes: “There are 49 dogs signed up to compete in a dog show. There are 36 more small dogs than large dogs signed up to compete. How many small dogs are signed up to compete?”

I took it seriously, knowing there must be a trick or it wouldn't be controversial. But I quickly dismissed questions like, "How do you draw the line between large and small dogs?" as being uninteresting, and decided to take the problem at face value.

It's one of the easiest, most basic algebra problems. If you are wondering why an algebra problem was given to second graders—well, I've seen children even younger solve such puzzles through logic and an intuitive sense of the world that school hasn't yet had a chance to squeeze out of them.

So. Simple algebra. (It's a lot faster and easier than it looks, written out, but bear with me.)

- Let L = the number of large dogs.

- Let S = the number of small dogs

- We know L + S = 49

- Therefore L = 49 - S

- We know S = L + 36

- Therefore S = (49 - S) + 36 [substituting (49 - S) for L]

- Therefore S = (49+36) - S

- Therefore S = 85 - S

- Therefore 2S = 85 [adding S to both sides]

- Therefore S = 42.5

That's where the Algebra I student stops. The second grader knows better: "Half a dog? Are you crazy? Math makes no sense."

Math makes plenty of sense. All too often, math textbooks and tests do not.

The teacher whose homework assignment caused the kerfuffle admitted that the problem itself was wrong, casting the blame on the school district. She confirmed, however, that 42.5 would be the correct answer, "if done at an age appropriate grade."

No. Just no.

This is why bridges fall down.

Math word problems that purport to be about real-world situations should reasonably conform to reality. If you want to use those numbers, maybe try something like, "Tom and Lisa shared a box of 49 Krispy Kreme donuts. Tom ate 36 more than Lisa. How many did Tom eat?" ("Enough for a massive stomach ache," would be my answer.) Or just change the numbers! (Maybe the error was a misprint.)

The only correct answer to the problem as stated is, "This question is not answerable."

If we teach our children that it's okay to plug numbers into an algorithm (or a computer model) and make decisions based on the results without considering whether or not the answers actually make real-world sense; if we teach them that giving a wrong answer is better than saying, "we don't know," or even "we can't know"; then bridges are going to collapse, windows are going to blow out of airplanes, economies are going to crash, countries are going to start wars, and people are going to die.

Although it made Tampa's NBC News affiliate only two days ago, the story is at least five years old, as you can see here (if you don't mind the language).

For what it's worth, this was my thought process once I realized that the problem was the problem.

- The total number of dogs, 49, is an odd number.

- The only way two integers can sum to an odd number is if one of them is odd, and the other is even.

- The number of small dogs and the number of large dogs differs by 36, which is an even number.

- The only way two integers can differ by an even number is if they are either both odd, or both even.

- (2) and (4) are mutually exclusive conditions.

- Since dogs must be counted by positive integers and not fractions, the problem is not solvable.

There's one more difficulty in this puzzling and disturbing report.

The Tampa news team ends the story with their own solution:

The digital team from Nexstar affiliate WTAJ took a crack at it, with their own Olivia Bosar determining the following:

“You first subtract the 36 to group them as small dogs since you need at least 36 small dogs. You then divide the remaining 13 into two categories: large dogs and small dogs. But you have to divide them in a way that would give you the ability to create a class that’s X and a class that’s X+36. It’s not possible in this equation because 13 is a prime number.”

As a prime number, once you try to divide 13, you end up with a .5 in your answer, and, well, obviously, you can’t have half of a dog.

I give them credit for recognizing that you can't have half a dog, at least not if you want him alive enough to compete in a show. But what does the fact that 13 is a prime number have to do with anything? If you make the total number of dogs 51 instead of 49, then after you subtract 36 the number of remaining dogs is 15. Fifteen is not prime, but the problem is jut as insoluble.

Back in elementary school, I loved what was then called the "New Math." Working with sets, and other bases—I ate it up. (Tom Lehrer has a great song about it.) But today's Newer Math? I have my doubts.

I was wondering how I'd get a post out today, in which there is no time for actual writing. Then my grandson handed me this on a platter, which he dubbed, "The real reason I decided not to go to college." (This from one of the most learning-obsessed people I know.) Porter, you will love what he says about Economics.

Also, this is for all of my fellow Gilbert & Sullivan enthusiasts.

I'm not particularly aware of what parents and teachers worry about these days, having long passed that stage of life, but I know that for a long time, parents have been concerned that kids are not doing the things that concerned my generation's parents and teachers because we were actually doing them. Case in point: Reading.

For decades, schools have found it necessary to push children to read books. And I can see why, given the number of adults who simply don't read books, once they are done with school. They weren't reading for pleasure back when they were captive students, but rather because books were assigned—so it's hardly surprising that they don't read now that they are free.

I hear responsible parents these days admonishing their children, "Put down your phone/iPad/Nintendo and go read a book!" Or so I'm told; maybe they've given up by now. But I'm sure the schools are still telling kids to read. Pretty sure, at least.

That's not what I heard growing up. My parents were both avid readers, but I was more likely to hear, "Put down that book and go outside!" That wasn't exactly onerous, at least not when we lived in Upstate New York with a large, undeveloped section of land just across the street from our house. I spent nearly as many happy hours exploring the woods and fields as I spent exploring the worlds of my books. "Put down that book and get your chores done" was not quite as welcome a call.

Side Note: Our parents may have had a point. Here's something my dad wrote after I visited the eye doctor for a yet stronger glasses prescription.

Dr. O’Keefe never offers any advice for arresting Linda’s rapidly increasing near-sightedness except to make her get outdoors more and not let her bury her nose in a book. I think that we really need some advice that is better thought out. [More than 20 years later, the doctors could do no better than this when our eldest daughter was experiencing the same problem.]

Teachers and parents these days (where by "these days" I'm referring to anything after about 1980) have been so desperate to get kids to read that they have lowered their standards and expectations almost as if this were a limbo contest. "I don't care what he reads, as long as he's reading."

Contrast this with my mother, who tried to enlist the help of our elementary school librarian to get me to read something more challenging than the horse stories and science fiction I was devouring. Or my sixth grade teacher, who solemnly advised my father that "Linda should improve the quality of her reading." I'm certain that he was correct; I'm equally certain that my father's attempts to encourage me in that direction, beginning with bringing home from the library a Jules Verne compendium, were not a resounding success.

Reading has always been my passion, and in my eighth decade I have not yet outgrown horse stories and science fiction. However, I think even my sixth grade teacher would be pleased with my much-expanded selections. It's possible that the most credit for my habit of reading should go to the fact that we did not have a television in the house until I was seven years old, nor a computer till after I was married.

One thing I know for sure: there will always be an X, a Y, and parents and teachers who will exhort their children, "Stop doing X and go do Y."