Be warned: as usual, when we get more grandchild time, you get more grandchild fare. Here's a Joseph story from our trip to the Swiss Transport Museum in Luzern, about which I hope to report more later.

Near the space travel hall there is a wall of curved couch-like segments that kids love to climb on, over, and around. A couple of somewhat older children—I'd say aged 10 or 11—were also there. One of them, clearly revelling in some newly-acquired foreign vocabulary, flopped down on a curve and exclaimed, with a heavy accent, "What da f***?!"

Joseph, our tape-recorder child, promptly flopped himself down in imitation, and loudly proclaimed his own interpretation: "What da fun?!"

Permalink | Read 2128 times | Comments (0)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

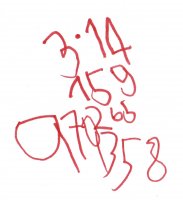

I had a wonderful belated birthday celebration here in Switzerland, including a long, leisurely mother/daughter breakfast of pastries and free-ranging conversation at a local bakery while the guys and kids played at home. Both Vivienne and Joseph made me birthday cards, all cute in an adorable 18-month- and three-year-old grandchild way. Then again, one of Joseph's was cute in a decidedly not-three-year-old grandchild way. He refused to write "Happy Birthday," or "I love you," or "Grandma," or even "Joseph." But when Janet suggested that he could write numbers instead, he went to work with alacrity. Here's one page of his unprompted, unscripted response:

Permalink | Read 2497 times | Comments (5)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

July 14

Come, Christians, Join to Sing arr. Carlton R. Young

I'm sorry I can't find an example of anyone singing this arrangement, but the link will show you a sample of the sheet music.

July 21

O Great God by Bob Kauflin, arr. Joey Hoelscher

What I Saw In America by G. K. Chesterton (originally published 1922)

What I Saw In America by G. K. Chesterton (originally published 1922)

In 1921, G. K. Chesterton embarked on a lecture tour of the United States, and "everybody who goes to America for a short time is expected to write a book," so he did. This is no travelogue, however, but a set of serious essays inspired by Chesterton's observations.

It was only after graduating from college that I began to have an appreciation for the study of history. During my school years, the world was divided into "math/science people" and "English/history people." Being both good at math and an avid reader of science fiction, I was clearly one of the former. The reasoning behind this idea that one should not be good at, nor even interested in, all of the above escapes me as much as why I allowed myself to be so labelled.

While I would still choose reading and mathematics as of all the school subjects the most important for a child to master "early and often," I'd now put history a close third. I know of no other way to counter what C. S. Lewis called "chronological snobbery." It is far, far too easy for us to assume that progress only goes in one direction, that we have come "sooo far" from our predecessors socially as well as technologically. Reading history—especially writings that were current at the time—is the best way I know to understand that the people of the past were human beings like us rather than incomprehensible, unenlightened savages. To use an extreme example, it is easy to hate Adolph Hitler, almost as easy to revile the German people (and others) for not rebelling wholesale against the evil he brought on, and pathetically easy to assure ourselves that we would never let anything like that happen today. But never in all my schooling did I experience a serious attempt to understand historical events and situations as they were seen at the time by intelligent, thoughtful, normal people. We are appalled when Hitler speaks of the "Jewish problem," but don't make the effort to figure out what it was about the circumstances that made the Jews a particularly acceptable scapegoat. We're taught, as I was in school, that white southerners were evil to resist having their children bussed across town to attend black schools; I never had an appreciation for the many non-racially-motivated reasons not to place your child on that sacrificial altar until I spoke with someone who had lived through it. By no means do I subscribe to the theory that in the attacks of September 11, 2001 we "got what we deserved," but if we—or at least our policy analysts—had been in the habit of looking at ourselves and our actions through other eyes, we at least would not have been so surprised.

What I Saw in America is a great antidote. Chesterton is so insightful that it's easy to think of him as outside of his cultural and historical surroundings, but he was writing nearly a century ago. Think for a minute of what the world was like during his 1921 American tour. (Maybe you do this kind of thinking all the time, but it's new for me.) The Civil War was closer to 1921 than the Korean War to 2013. Arizona and New Mexico had only been states for nine years, and last of the Indian Wars were but a few years past. Prohibition was new. Harding was the newly-elected president. The Panama Canal was a mere seven years old. Chesterton's essays glow with the perspectives of both another culture (British) and another time.

I don't claim Chesterton is always easy to understand, especially for someone who knows little about America in that era, and who doesn't possess the everyday knowledge he expects to be common to his British audience. But he's always worth reading, nonetheless. Very thought-provoking, but alas, not further-post-provoking at this time. Life calls.

This quotation from an interview with Anne Fine set me to thinking. (H/T Stephan)

[I] hate the way that we have weeded out the things that I remember made my heart lift in primary school, and were transforming in my secondary education. I mean, we did so much singing when I was at school – folk songs, hymns, we sang everything. But now that seems to have gone, along with the language of the Book of Common Prayer and so much classic poetry. And school days are horrifically long if pretty well everything you are doing lacks colour and style, just for the sake of 'relevance' and 'accessibility'".

Music was a big part of my own elementary school, though not being British we missed out on the BCP. Music lessons started in grade four (of six) for strings and in fifth for band instruments. Chorus started at about the same time, and in two of the three schools I experienced, we were singing three-part harmony. (Occasionally four, as in one school we had a set of older boy twins whose voices had mostly changed.) These musical activities were optional, but what stands out most in my mind in contrast to today is that nearly every classroom had a piano, and many of the teachers could play it. (So could some of the students, and we were allowed to use it some ourselves outside of class.) We sang patriotic songs, folk songs, hymns, Negro spirituals, and children's songs. And most of these we read out of music books. Not that we were specifically taught much in the way of reading music, but we were expected to absorb basic skills simply by observing the relationship between the printed notes and what we sang.

I should note that these were not "music magnet schools" but ordinary public elementary schools in a small village/rural school district in the late 1950's and early 60's.

Our own children had a fantastic music teacher in elementary school, there's no doubt about that, and their musical education outside of school was far greater than mine, with the availability of private music lessons, youth orchestras, and excellent church choirs. And being in the South, their high school chorus still sang the great Western choral music, which had already been all but banned in the schools we'd left behind in the North because it is largely church music. So I'm not complaining about that.

But something great has been lost in general education if there's no longer daily singing in the classroom, children graduate knowing nothing of the music of the past and without the most basic music-reading skills, and adults would rather attend a concert or plug into an iPod than raise their own voices in song.

I don't think, based on the interview, that I would like Anne Fine's books. But she's spot on in the quote. "Relevance" and "accessibility" are two of the dirtiest words in the educationist's vocabulary.

What were your musical experiences in the early school years? How have they affected your adult life?

I'd rather be with family than almost anywhere, but it's a pity that we only manage to spend Independence Day with the Greater Geneval Award Marching Band about every other year. This is what we missed two days ago.

I've written more extensively about the band before, so I won't reiterate, but if you ever want to experience the true spirit of American Independence Day, visit Geneva, Florida on July 4th.

Is College Worth It? by William J. Bennett and David Wilezol (Thomas Nelson, 2013)

Is College Worth It? by William J. Bennett and David Wilezol (Thomas Nelson, 2013)

It is the best of times and the worst of times for education. From preschool through higher education, there has been a steady decline in the quality of public education in at least the half-century I’ve been observing it. If my father is to be believed—and he was always a very reliable source—it’s been declining for a lot longer than that. He was frequently appalled at my generation’s ignorance of basic history, geography, and literature. (He’d have said the same thing about basic arithmetic, but he was surrounded by engineers.) It doesn’t take much observation to realize that today the average American’s grasp of those subjects makes me look brilliant.

At the same time—and my father would concur—in some fields, for some people, knowledge and ability has soared. As a science fair judge, he was blown away by the scope and quality of the research done by high school students. His own high school had offered no math beyond trigonometry, and it was rare among high schools to offer even that. My high school offered only one Advanced Placement course—and that for seniors—whereas our children had at least a dozen to choose from, beginning as freshmen. And yet only a few students were actually prepared to take advantage of the generous offerings: back in fifth grade, I would have said the expectations of their teachers were well below those of my own, and far below those of my father’s.

Despite the best efforts of educators to mush us all into a sameness at any level—better all low than some higher than others—there has always been an upper class and a lower class when it comes to education, and there always will be. What I’ve been noticing is that the highs are getting higher, the lows are getting lower, and the middle class is rapidly descending—much as is happening with economic measures.

I’m hoping the economic situation does not lead to revolution, but there’s a crisis and a revolution coming in education and I say, bring it on! (More)