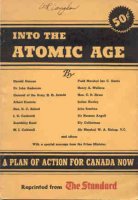

Into the Atomic Age: A Plan of Action for Canada Now edited by Sholto Watt (Montreal Standard Publishing Company, 1946)

Into the Atomic Age: A Plan of Action for Canada Now edited by Sholto Watt (Montreal Standard Publishing Company, 1946)

This, the fourth of my father's collection of early post-Hiroshima books (see here, here, and here), is as fascinating as the others, although the fascination has less to do with atomic energy and atomic bombs than with the immediate post-war culture.

The Greatest Generation was, in a word, terrified. For the scientists who developed the Bomb itself, the politicians attempting to address the consequences of its very existence, and those whose business was social and political commentary, these were "what hath Man wrought?" times, just over a century after Samuel F. B. Morse's famous telegraph transmission.

In 1946, The Standard, a Canadian national weekly newspaper, published a series of essays on the subject of atomic energy. The contributors were diverse, from military men to scientists to politicians to prominent men from a variety of fields, whether or not they bore any relation to atomic energy. (Contract bridge, anyone? Ely Culbertson was one of them.)

In the early years of my adulthood, I remember hearing people express great fear that we were headed towards a "one world government." They were suspicious of the United Nations, and viewed every international agreement through the lens of how it might affect our national sovereignty. I confess I gave them little respect, because I saw not a shred of evidence that anyone was interested in forming a unified world government.

But I was young. Even if I did grow up with "duck and cover" drills in elementary school, and spent time pondering the feasibility of building a fallout shelter in our backyard, I was blissfully ignorant of the politics of it all. Almost to a man, the writers of these essays were convinced that the only alternative to nuclear annihiliation was for all nations to give up their sovereign rights to an international government—either entirely, or "only" in the right to maintain armed forces and to wage war. The United Nations was brand-new in those days, and much hope was expressed that it would become the entity that would rule the world.

Fear makes people do crazy things, and put up with crazy things done by their leaders. It wouldn't surprise me if more freedoms have been lost through fear than through outright conquest. Fortunately for us, the one-world-government crazy idea never made it off the ground, though we've certainly lost plenty of freedom through fear—the Patriot Act and the bailout of companies "too big to fail," for example.

Be that as it may, here's a sampling of what people were thinking 70 years ago in response to what they perceived as the world's biggest threat. Text in bold is my own emphasis.

The picture of the next war thus becomes one of surprise, of sudden and unannounced aggression, of an “anonymous war,” in which the aggressor leaves no traces, mobilizes no armies, proclaims no hostilities.” A city might explode one night, another the next. In one night, a flight of rockets might demolish 20 cities and kill 40 million.

“This is the one-minute war of the future,” the scientists state. “This is the war that will be hanging over the heads of the nations of the world when all have possessed themselves of atomic explosive and sit in fear and trembling, wondering when their neighbor—or a country on the opposite side of the globe—may press the fateful key. … This picture is not projected a century or even half a century into the future; it is a possibility five years from now, a certainty in 15.”

To every man and woman it may be said with certainty that to secure a world authority is now part of the business of personal survival.

The more deeply one ponders the problems with which our world is confronted in the light … of the implications of the development of atomic energy, the harder it is to see a solution in anything short of some surrender of national sovereignty.

We are afraid that the understanding and sympathy that binds us together may not be as strong as the conflicts of national interest and the dark hates that threaten to separate us. Atomic energy in itself does not endanger us. It is the possible use of atomic energy by persons and nations motivated by hate that causes our fear.

The establishment of this world government must not have to wait until the same conditions of freedom are to be found in all three of the great powers. While it is true that in the Soviet Union the minority rules, I do not consider that internal conditions there are of themselves a threat to world peace. (Albert Einstein)

That one is evidence, as if any more were needed, that intellectual brilliance and practical sense do not necessarily reside together.

The scientists give us five short years in which to save ourselves and the world…. Five years in which we must build out of the present infant United Nations organization a world government capable of outlawing wars and the causes of wars. Five years in a world in which, from the dawn of Christianity from which our own democracy stemmed, it took nearly 2,000 years for our democracy to develop. Five years in which to project ourselves 1,000 years in maturity, in understanding, in social development.

But not to worry. The public schools can fix the problem.

I am optimistic enough to think that, with success in the intermediate and short-term period, we have a margin of twenty years in which to work. The long-term programme, the twenty-year programme, is the establishment of world government under principles of law, justice and human freedom. Such a world government cannot be imposed by force. It cannot be successfully negotiated by the statesmen of the nations of the earth. The plain fact is that world government requires as its foundation a moral and psychological sense of world community, and that foundation does not exist. To impose or to negotiate world government under existing conditions of prejudice and hate would do nothing more than set the stage for world civil war. The minds and hearts of men are not yet prepared for a world of law, justice and mercy.

We in North America are not prepared. Too many men despise women. Too many women despise their servants. Too many white men despise black men. Too many Christians despise Jews. This lack of sympathy and respect extends not only across group lines, but also within the groups themselves.

I feel that with twenty years to spare, the moral and psychological foundation for world peace can be laid. The hope is not that hundreds of years of history, tradition and custom will automatically and suddenly change their direction. The hope lies in the fact that it takes only a period of about a dozen years to implant a basic culture in the minds of a man—the period of childhood between the age of two and the age of 14.

The following may sound absurd now, but I know for a fact that Kodak built a special bomb-proof facility in Rochester, New York so that they could continue to manufacture paper in the event of nuclear war.

Drastic changes in defence measures would be called for, including the abandonment of all large cities, the decentralization of communications and the placing of all important factories far underground.

Not everyone was all gloom-and-doom. Some were downright science fiction in their ambitions.

The world-shaking discovery of atomic power, the greatest since the discovery of fire, can have only one of two end-results: either the unparalleled shattering of our civilization through atomic blasts, or an unparalleled era of peaceful science and mass happiness.

We have now within our grasp the means for creating an abundant life for all peoples of the world. Even before the development of atomic energy this was true, but now that we have tapped this tremendous new source of power, perhaps within half a century all nations can be raised to the same economic level occupied by the most advanced nations today.

There has never before been a discovery equal to that of atomic energy. The greatest discoveries of the past have advanced the material aids to humanity but a few years, but the forward move in the development of atomic energy must be measured in centuries. It can open the door to an age of plenty without revolution or war. It can make equality of opportunity a reality in our day. It can give the backward areas a chance to reach equality with others.

Some were downright nuts.

Why go slowly shepherding great liners through the locks on either side of the Culebra Cut when you could readily use atomic energy to blast a sea-level canal from ocean to ocean? (You would, of course, have to arrange for the temporary evacuation of all the population of the canal zone, but that, in these days of mass transfers of population, is perhaps not impossible.)

How many people realize that we could alter the entire climate of the North Temperate zones by exploding a few dozen or at most a few hundred atomic bombs at an appropriate height above the polar regions?

As a result of the immense heat produced, the floating polar ice-sheet would be melted; and it would not be re-formed. It is a relic from the last Ice Age, and survives today because most of the heat of the sun is reflected from its surface.

If it were once melted, most of the sun’s heat during the polar summer would be absorbed by the water and raise the temperature of the Arctic Ocean. Ice would form again each winter, but it would not cover nearly so large an extent as now, and would be thick enough to be melted in the succeeding summer.

As a result, the climate of Scandinavia would become more like that of Southern England, and the climate of Southern England would become much like that of Portugal.

As usual with all grandiose projects, there are snags.

Thus with the northward movement of the warm temperate and cool temperate zones, the arid zone would move too; and the countries which had the prospect of being turned into the Sahara of the future might reasonably object!

Perhaps it would be best to begin in a small way, by melting a small chunk of the ice-sheet with the aim, say, of slightly ameliorating the climate of Nova Scotia and Labrador, and seeing what happened elsewhere, before attempting anything further.

And we think we have climate change problems now.

Some writers had a better grasp of political realities than others.

We should do well to take stock from time to time of our original purpose in establishing the UNO [United Nations]. What was that purpose? The commonest reply perhaps would be, “To preserve peace.” For many years statesmen have been in the habit of saying, “The greatest interest of our country is Peace.” They have said that usually with complete sincerity and in bad confusion of thought.

For it is not true.

Any nation which suffered invasion would fight if it could. That is to say, it would sacrifice peace for the purpose of defending its national independence. Which means that we do not put peace first; we put defence first: the right to existence, national survival. And no international organization can succeed if it ignores this truth that defence, security, the right to life, must in the purpose of men come before mere peace. We could have had peace by submission to Hitler and Hirohito; we refused it on those terms.

But that brings us to the question: “What is defence? What rights of nations must an international organization defend if its purpose is to be fulfilled? Russia declares that its rights of defence must include “friendly” governments in the whole of Eastern Europe. What precisely does “Friendly” mean? More than once Russia has described Switzerland as “unfriendly and semi-Fascist.” On one occasion Russia refused participation in an international conference on aviation because Switzerland was included. If each nation is to claim in the name of defence conformity with its own special views to the extent which Russia seems to claim that conformity, a workable international organization for collective security is going to be extremely difficult to establish.

Despite the book's small size, there's a lot more to Into the Atomic Age, from following a spelunker deep into a cave in search of a place to set up an underground factory, to the convincing argument that there is no effective way for international inspections to prevent a country that has nuclear energy from also being able to make nuclear bombs. I wish those who negotiated our treaty with Iran had read this book.