This is the third time I've used that handy title for a post. It may be recursive.

The inspiration for this occasion is a lament from Village Diary, by Miss Read (Dora Jessie Saint). What is remarkable is not the sentiment, but that it was written in 1957.

The child today, used as he is to much praise and encouragement, finds it much more difficult to keep going as his task gets progressively long. Helping children to face up to a certain amount of drudgery, cheerfully and energetically, is one of the biggest problems that teachers, in these days of ubiquitous entertainment, have to face in our schools.

I was going to make this Day of Thanksgiving about music in general, for which I am indeed very thankful. I have to admit that I usually prefer to listen to instrumental, rather than vocal, music. But there is something about singing that sets it apart. Nothing can be more personal than when your instrument is your own body. It's very handy, too: your instrument is with you wherevery you go, and no one makes you check it with the luggage when you fly. On the other hand, a flute never catches the flu....

Best of all, singing is accessible. If there's ever been a culture that doesn't sing, I've never heard of it. Little children sing with great joy, at least until someone's unkind comment convinces them that they can't. With very, very few exceptions, people who say they can't sing—like people who say they can't do math—are victims either of someone's deliberate cruelty or of someone's poor teaching. Even those too embarrassed to sing in front of others can enjoy singing in the shower.

My father was always told as a child that he couldn't sing. I'm not a fan of college fraternities, but his story reminds me that not all fraternities fit the stereotype.

My parents felt that since I would be living at home I should join a fraternity in order to have some on-campus experiences. First I was rushed by my father’s former fraternity, but to me it seemed to contain all the undesirable elements of fraternities—they boasted about how many football players were members, how many parties they had, an atmosphere that bothered me—and I quickly lost interest. Later a faculty friend suggested his former fraternity and while I liked it better it still didn’t really appeal to me. About mid year I became acquainted with Alpha Kappa Lambda, a fraternity whose members neither smoked nor drank and that one I joined.

Nearly a third of the fraternity membership comprised music majors, and they prided themselves on their fine fraternity chorus. I no sooner had committed myself to the fraternity than the chorus director asked me what part I sang. I had always known that I could not sing and people, including my parents, never hesitated to tell me that I couldn’t sing. So that was my reply to the director. He called me over to the piano and had me sing scales and other notes as he played them. After several minutes of this he said, “You are a second tenor.” Thus I became a member of the chorus. He had recognized that although I did not have a solo voice, I could match the piano tones accurately and thus could follow others and blend in with their notes.

This meant a great deal to me and brought much pleasure. And I owe much to the chorus leader for leading me into singing. In college the chorus sang quite often for various events and it allowed me to find a place in the church choir. And all three years I sang with the chorus we took first place in the annual competition among living group choruses. It also meant much to me after I left college....

| "Did you know that singing and talking involve two different parts of the brain? People who have lost speech due to a stroke can often still sing. Stutterers can usually sing fluently. The local pizza shop recognized a friend of mine by the fact that she would sing her pizza order." |

Dad sang with a barbershop quartet after college, but what I remember best is his singing at home, usually folk songs, from Old World ballads to sea shanties to cowboy laments. That's a great gift to give a child. I wish I had given it to my own children, but I'm not as resilient as my father was, and still bear my own scars, from wounds inflicted by my junior high school music teacher (who was also—until she drove me out—my church children's choir director; it was a very small town).

Singing knits people together. It's a tragedy that family singing is a lost art. But that is one singing gift we were able to give our own children—not that we gave the gift, but we did put them (and ourselves) in a position to receive it. We have a set of musical friends with whom nearly every get-together ends with people gathered around the piano, singing. That's my idea of a party! Depending on who is present, and the time of the year, the music may be choir anthems, or hymns, or Beatles songs, or Christmas carols, or popular music I've never heard of, but it's all wonderful fun. The following video is one example (there are more people behind the camera). It's my video, but I had refrained from posting it rather than bother to get permission from the singers. But now it has been made public, so I figure it's fair game. :) By the way, don't be tempted to think badly of the people staring at their phones—they're reading the song lyrics.

I'm thrilled that our children and grandchildren know the joy of singing together. The adults and several of the children all play the piano, but you don't need that skill to sing as a family. They also sing a cappella. Unaccompanied singing can be beautiful, and teaches a good sense of harmony. And even though it's not my taste, there's always karaoke....

And it's never too early or too late. Children can sing in groups in school. Many churches and communities have children's choirs. The hardest years, I've found, are the middle ones, when one must juggle babies, and children ... and children's schedules. But after that, the opportunities open up again, with church choirs and community choruses. A few church choirs are too good, or require too much of a commitment, for timid singers, but most welcome anyone who will even try to sing on pitch—and the best way I know to learn to sing is to sing with others.

Go. Sing. Lift up your hearts and your voices, with thanksgiving.

Permalink | Read 1193 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

This observation needs reviving again, from John Caldwell Holt.

One of the saddest things I've learned in my life, one of the things I least wanted to believe and resisted believing for as long as I could, was that people in chains don't want to get them off, but want to get them on everyone else. Where are your chains? they want to know. How come you're not wearing chains? Do you think you are too good to wear them? What makes you think you're so special?

Permalink | Read 1188 times | Comments (0)

Category Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Clean water, coming freely—hot or cold—at a touch, on demand. Not just for my community, but at our own house—several places in and around our house, in fact. That is wealth unheard of for much of the world, stretching along dimensions of both space and time.

Granted, others have been richer in the taste of their water. In my memory, no water in the world has ever matched that which flowed in the streams of the Adirondack Mountains, where I hiked as a child with my father. Our tap water is bland, with the dull sameness that permeates pasteurized milk, orange juice, and cider, and accompanies produce and meats bred and processed to be convenient, standard, and safe. But tap water is fine with me, because if there's a bottled spring water that even hints at that glorious mountain spring taste, I've never experienced it. In fact, I don't believe it exists, because the processing needed to make it safe to transport and sell kills the flavor along with the germs.

But plentiful, clean water, bland or not, is one of the greatest blessings in the world. Water for drinking, water for cooking, water for washing, water for flushing toilets, water for swimming, water for tea and squirt gun fights and baptisms.

Then there's the other side. All that blessed water flowing in to our homes requires a safe channel to remove it for its own cleansing after it has finished with ours. Sewage removal and treatment is something we usually take for granted—until it stops. The dread of sewage backups keeps us vigilant to minimize our water use during hurricane recovery, and grateful for the emergency generators struggling to keep the county's pumping stations and sewage treatment plants functioning.

I'm reminded of the following, from the Book of Common Prayer's baptismal service:

We thank you, Almighty God, for the gift of water. Over it the Holy Spirit moved in the beginning of creation. Through it you led the children of Israel out of their bondage in Egypt into the land of promise. In it your Son Jesus received the baptism of John and was anointed by the Holy Spirit as the Messiah, the Christ, to lead us, through his death and resurrection, from the bondage of sin into everlasting life.

We thank you, Father, for the water of Baptism. In it we are buried with Christ in his death. By it we share in his resurrection. Through it we are reborn by the Holy Spirit. Therefore in joyful obedience to your Son, we bring into his fellowship those who come to him in faith, baptizing them in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.

We thank you, Almighty God, for the gift of water.

Permalink | Read 1188 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Inspired by my previous post, Presents of Mind, and a few incidents this year that left me temporarily without blessings which I usually take for granted, I'm starting a Seven Days of Thankgiving series. They'll be in no particular order. Seven days isn't nearly enough, but—as a good friend keeps reminding me—better done than perfect.

It doesn't take long for a power outage, such as we experienced with Hurricane Irma, to make one realize the blessing of reliable electric power. One of my happiest childhood memories is of an ice storm that forced us to use candles for light, cook over a camp stove, and have the whole family sleep huddled together on the floor by the fireplace. But our power outage didn't affect our water supply, nor our septic system, and it was winter, so there was no need to worry about spoiled food. If the few days it lasted was too short a time for a child's sense of adventure, I'm sure my mother was thrilled when the power came back on. I wasn't the one who had to worry about washing diapers! And there was nothing I could call delightful about a power outage in the middle of a Florida September, other than being provoked to gratitude. I can't imagine what the people of Puerto Rico and other Caribbean islands are experiencing.

Permalink | Read 1261 times | Comments (4)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The Charlotte, North Carolina, area is home to some of my favorite people, so when I saw that this video came from Charlotte, I was naturally drawn to it. It's under two minutes long, and definitely worth your time.

I don't need to read anyone's comments (it's making the rounds on Facebook) to hear the negative responses: The the lead character is a while, middle class male. His sweet, blonde wife and his adorable two children, one girl and one boy, send him off from his lovely, suburban home to his first-world office job.

Just. Don't. Go. There.

You'll miss everything important.

Build your own mental video (or film it!) with the characters and situations you think it should have.

And be thankful.

I know it's too early for Christmas videos. It's not even Thanksgiving yet, let alone Advent, let alone Christmas. But for some reason I'm not finding the Christmas-decorations-go-up-before-Hallowe'en problem so annoying this year. Maybe I've given up on trying to fit a proper Advent of solemn, thoughtful preparation followed by 12 glorious days of Christmas into modern, secular, American society. But, aside from the maddening habit of ending the playing of Christmas carols at noon on the 25th, this isn't really modern America's fault. Choirs as well as commercial establishments must begin preparations for the Christmas season early, if they hope to make a good showing in December, so I've been singing Christmas music for weeks already. In my childhood days, December 24 often saw saw us engaged in last-minute shopping, and certainly in last-minute wrapping, but that won't do when one's family is a lot further away than over the river and through the woods, and tucking a small gift into a child's stocking late at night may require international travel—without benefit of a reindeer-powered sleigh. I'm actually grateful that Christmas sales started as soon as they did.

Any church musician knows that it's important to get it right—and equally important to be flexible, charitable, and to choose one's battles.

Permalink | Read 1251 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

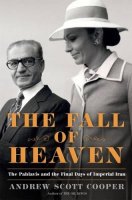

The Fall of Heaven: The Pahlavis and the Final Days of Imperial Iran by Andrew Scott Cooper (Henry Holt, 2016)

The Fall of Heaven: The Pahlavis and the Final Days of Imperial Iran by Andrew Scott Cooper (Henry Holt, 2016)

People were excited at the prospect of "change." That was the cry, "We want change."

You are living in a country that is one of the wealthiest and most powerful in the world. You enjoy freedom, education, and health care that was beyond the imagination of the generation before you, and the envy of most of the world. But all is not well. There is a large gap between the rich and the poor, and a widening psychological gulf between rural workers and urban elites. A growing number of people begin to look past the glitter and glitz of the cities and see the strip clubs, the indecent, avant-garde theatrical performances, offensive behavior in the streets, and the disintegration of family and tradition. Stories of greed and corruption at the highest corporate and governmental levels have shaken faith in the country's bedrock institutions. Rumors—with some truth—of police brutality stoke the fears of the population, and merciless criminals freely exploit attempts to restrain police action. The country is awash in information that is outdated, wrong, and being manipulated for wrongful ends; the misinformation is nowhere so egregious as at the upper levels of government, where leaders believe what they want to hear, and dismiss the few voices of truth as too negative. Random violence and senseless destruction are on the rise, along with incivility and intolerance. Extremists from both the Left and the Right profit from, and provoke, this disorder, knowing that a frightened and angry populace is easily manipulated. Foreign governments and terrorist organizations publish inflammatory information, fund angry demonstrations, foment riots, and train and arm revolutionaries. The general population hurtles to the point of believing the situation so bad that the country must change—without much consideration for what that change may turn out to bring.

It's 1978. You are in Iran.

I haven't felt so strongly about a book since Hold On to Your Kids. Read. This. Book. Not because it is a page-turning account of the Iranian Revolution of 1978/79, which it is, but because there is so much there that reminds me of America, today. Not that I can draw any neat conclusions about how to apply this information: the complexities of what happened to turn our second-best friend in the Middle East into one of our worst enemies have no easy unravelling. But time has a way of at least making the events clearer, and for that alone The Fall of Heaven is worth reading.

On the other hand, most people don't have the time and the energy to read a densely-packed, 500-page history book. If you're a parent, or a grandparent, or work with children, I say your time would be better spent reading Hold On to Your Kids. But if you can get your hands on a copy, I strongly recommend reading the first few pages: the People, the Events, and the Introduction. That's only 25 pages. By then, you may be hooked, as I was; if not you will at least have been given a good overview of what is fleshed out in the remainder of the book.

A few brief take-aways:

- The road to hell is paved with good intentions. Jimmy Carter is undoubtedly an amazing, wonderful person; as my husband is fond of saying, the best ex-president we've ever had. But in the very moments he was winning his Nobel Peace Prize by brokering the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty at Camp David, he—or his administration—was consigning Iran to the hell that endures today. Thanks to a complete failure of American (and British) Intelligence and a massive disinformation campaign with just enough truth to keep it from being dismissed out of hand, President Carter was led to believe that the Shah of Iran was a monster; America's ambassador to the United Nations, Andrew Young, likened the Shah to Adolf Eichmann, and called Ruhollah Khomeini a saint. Perhaps the Iranian Revolution and its concomitant bloodbath would have happened without American incompetence, disingenuousness, and backstabbing, but that there is much innocent blood on the hands of our kindly, Peace Prize-winning President, I have no doubt.

- There's a reason spycraft is called intelligence. Lack of good information leads to stupid decisions.

- Bad advisers will bring down a good leader, be he President or Shah, and good advisers can't save him if he won't listen.

- The Bible is 100% correct when it likens people to sheep. Whether by politicians, agitators, con men, charismatic religious leaders (note: small "c"), pop stars, advertisers, or our own peers, we are pathetically easy to manipulate.

- When the Shah imposed Western Culture on his people, it came with Western decadence and Hollywood immorality thrown in. Even salt-of-the-earth, ordinary people can only take so much of having their lives, their values, and their family integrity threatened. "It does not do to leave a live dragon out of your calculations."

- The Shah's education programs sent students by droves to Europe and the United States for university educations. This was an unprecedented opportunity, but the timing could have been better. The 1960's and 70's were not sane years on college campuses, as I can personally testify. Instead of being grateful for their educations, the students came home radicalized against their government. In this case, "the Man," the enemy, was the Shah and all that he stood for. Anxious to identify with the masses and their deprivations, these sons and daughters of privilege exchanged one set of drag for another, donning austere Muslim garb as a way of distancing themselves from everything their parents held dear. Few had ever opened a Quran, and fewer still had an in-depth knowledge of Shia theology, but in their rebellious naïveté they rushed to embrace the latest opiate.

- "Suicide bomber" was not a household word 40 years ago, but the concept was there. "If you give the order we are prepared to attach bombs to ourselves and throw ourselves at the Shah's car to blow him up," one local merchant told the Ayatollah.

- People with greatly differing viewpoints can find much in The Fall of Heaven to support their own ideas and fears. Those who see sinister influences behind the senseless, deliberate destruction during natural disasters and protest demonstrations will find justification for their suspicions in the brutal, calculated provocations perpetrated by Iran's revolutionaries. Others will find striking parallels between the rise of Radical Islam in Iran and the rise of Donald Trump in the United States. Those who have no use for deeply-held religious beliefs will find confirmation of their own belief that the only acceptable religions are those that their followers don't take too seriously. Some will look at the Iranian Revolution and see a prime example of how conciliation and compromise with evil will only end in disaster.

- I've read the Qur'an and know more about Islam than many Americans (credit not my knowledge but general American ignorance), but in this book I discovered something that surprised me. Two practices that I assumed marked every serious Muslim are five-times-a-day prayer, and fasting during Ramadan. Yet the Shah, an obviously devout man who "ruled in the fear of God" and always carried a Qur'an with him, did neither. Is this a legitimate and common variation, or the Muslim equivalent of the Christian who displays a Bible prominently on his coffee table but rarely cracks it open and prefers to sleep in on Sundays? Clearly, I have more to learn.

- Many of Iran's problems in the years before the Revolution seem remarkably similar to those of someone who wins a million dollar lottery. Government largess fueled by massive oil revenues thrust people suddenly into a new and unfamiliar world of wealth, in the end leaving them, not grateful, but resentful when falling oil prices dried up the flow of money.

- I totally understand why one country would want to influence another country that it views as strategically important; that may even be considered its duty to its own citizens. But for goodness' sake, if you're going to interfere, wait until you have a good knowledge of the country, its history, its customs, and its people. Our ignorance of Iran in general and the political and social situation in particular was appalling. We bought the carefully-orchestrated public façade of Khomeini hook, line, and sinker; an English translation of his inflammatory writings and blueprint for the establishment of an Islamic republic in Iran came nine years too late, after it was all over. In our ignorance we conferred political legitimacy on the radical Khomeini while ignoring the true leaders of the majority of Iran's Shiite Muslims. The American ambassador and his counterpart from the United Kingdom, on whom the Shah relied heavily in the last days, confidently gave him ignorant and disastrous advice. Not to mention that it was our manipulation of the oil market (with the aid of Saudi Arabia) that brought on the fall in oil prices that precipitated Iran's economic crisis.

- The bumbling actions of the United States, however, look positively beatific compared with the works of men like Muammar Gaddafi of Libya, and Yasser Arafat and his Palestine Liberation Organization, who funded, trained, and armed the revolutionaries.

- The Fall of Heaven was recommended to me by two Iranian friends who personally suffered through, and escaped from, those terrible times.

I threw out the multitude of sticky notes with which I marked up the book in favor of one long quotation from the introduction. It matters to me because I heard and absorbed the accusations against the Shah, and even thought Khomeini was acting out of a legitimate complaint with regard to the immorality of some aspects of American culture. Not that I paid much attention to world events at the time of the Revolution, being more concerned with my job, our first house, a visit to my in-laws in Brazil, and the birth of our first child. But I was deceived by the fake news, and I'm glad to have a clearer picture at last.

The controversy and confusion that surrounded the Shah's human rights record overshadowed his many real accomplishments in the fields of women's rights, literacy, health care, education, and modernization. Help in sifting through the accusations and allegations came from a most unexpected quarter, however, when the Islamic Republic announced plans to identify and memorialize each victim of Pahlavi "oppression." But lead researcher Emad al-Din Baghi, a former seminary student, was shocked to discover that he could not match the victims' names to the official numbers: instead of 100,000 deaths Baghi could confirm only 3,164. Even that number was inflated because it included all 2,781 fatalities from the 1978-1979 revolution. The actual death toll was lowered to 383, of whom 197 were guerrilla fighters and terrorists killed in skirmishes with the security forces. That meant 183 political prisoners and dissidents were executed, committed suicide in detention, or died under torture. [No, I can't make those numbers add up right either, but it's close enough.] The number of political prisoners was also sharply reduced, from 100,000 to about 3,200. Baghi's revised numbers were troublesome for another reason: they matched the estimates already provided by the Shah to the International Committee of the Red Cross before the revolution. "The problem here was not only the realization that the Pahlavi state might have been telling the truth but the fact that the Islamic Republic had justified many of its excesses on the popular sacrifices already made," observed historian Ali Ansari. ... Baghi's report exposed Khomeini's hypocrisy and threatened to undermine the vey moral basis of the revolution. Similarly, the corruption charges against the Pahlavis collapsed when the Shah's fortune was revealed to be well under $100 million at the time of his departure [instead of the rumored $25-$50 billion], hardly insignificant but modest by the standards of other royal families and remarkably low by the estimates that appeared in the Western press.

Baghi's research was suppressed inside Iran but opened up new vistas of study for scholars elsewhere. As a former researcher at Human Rights Watch, the U.S. organization that monitors human rights around the world, I was curious to learn how the higher numbers became common currency in the first place. I interviewed Iranian revolutionaries and foreign correspondents whose reporting had helped cement the popular image of the Shah as a blood-soaked tyrant. I visited the Center for Documentation on the Revolution in Tehran, the state organization that compiles information on human rights during the Pahlavi era, and was assured by current and former staff that Baghi's reduced numbers were indeed credible. If anything, my own research suggested that Baghi's estimates might still be too high. For example, during the revolution the Shah was blamed for a cinema fire that killed 430 people in the southern city of Abadan; we now know that this heinous crime was carried out by a pro-Khomeini terror cell. Dozens of government officials and soldiers had been killed during the revolution, but their deaths were also attributed to the Shah and not to Khomeini. The lower numbers do not excuse or diminish the suffering of political prisoners jailed or tortured in Iran in the 1970s. They do, however, show the extent to which the historical record was manipulated by Khomeini and his partisans to criminalize the Shah and justify their own excesses and abuses.

On our cruise to Mexico and Cuba with two of our grandchildren we were given a quick lesson in napkin folding. Naturally, the kids picked up on it better than the adults. This morning, a friend shared on Facebook a video of napkin folding techniques from the Ever & Ivy site. Unfortunately, I can't find the video on YouTube, so I can't embed it here, but hopefully the link will still work when I want to find it again. (There are also plenty of other napkin-folding instructional videos on YouTube.) Warning: I'm sure there are other good things about the Ever & Ivy site, but I can't recommend it in general. Good ideas + Bad language = I'll find the good ideas elsewhere, thank you. Except for the napkin folding—no words.

Permalink | Read 1304 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

It's all too easy, when one's eyes and mind are blurred by immersion in a sea of birth, death, and marriage data (or worse, the lack thereof), to forget that our ancestors were real people who laughed and cried and joked, just as we do. Then, every once in a while, you come upon something that wakes you up, such as a comment from Dr. Lewis Newton Wood, my great-great-great grandfather.

Lewis Newton Wood, son of David and Mercia (Davis) Wood, was born in southern New Jersey, on January 12, 1799. In 1821 he married Naomi Dunn Davis, born September 8, 1800, the daughter of David and Naomi (Dunn) Davis. Their first child, my great-great grandfather, was born in New Jersey, but the other seven of their children were born after they moved to upstate New York, near Syracuse. There, Lewis taught school, and in 1836 he graduated from the newly-formed Geneva Medical College, then part of Geneva College, which is now Hobart and William Smith. The medical school itself is now SUNY Upstate University. Perhaps the most famous graduate of the Geneval Medical College is Elizabeth Blackwell, Class of 1849, America's first licensed female physician.

Lewis moved to Chicago to practice medicine, and his family followed a year later, after which they migrated some 90 miles northwest to become some of the earliest settlers of Walsorth, Wisconsin. Eighteen years later they moved to their final destination, about 100 miles further north and west, to Baraboo, Wisconsin. There, Lewis died in 1868, and Naomi in 1883; they are buried in the Walnut Hill Cemetery in Baraboo. My great-great grandfather, incidentally, continued the family's northward and westward migration, moving first to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and finally to the west coast of Washington.

Lewis was not only a teacher, doctor, pioneer, and probably farmer (given that he lived on 360 acres in Big Foot Prairie), but also an amateur geologist who made notable scientific contributions, one of the founders of a school of higher education for girls in Baraboo, and a member of the Wisconsin state legislature. He even has his own Wikipedia entry, a link I incude with the standard Wikipedia cautionary tale about not believing everything you read, since some of the facts about him are wrong.

After that historical and genealogical excursion, I arrive at the reason for this post, the saying of Lewis Newton Wood's that struck my funny bone. It's taken from Gilbert Cope's Genealogy of the Sharpless Family Descended from John and Jane Sharples, Settlers Near Chester, Pennsylvania, 1682.

All my progenitors were Baptists of the Orthodox belief, i.e. Calvinists; and that is my own religious belief, except with the Calvinism pretty much left out.

Which may explain why this Baptist's funeral was held in a Methodist church. I know, it actually makes sense when you dig into the history of the Baptist Church, but still....

I like an ancestor with a sense of humor.

Another genealogical puzzle with my research and conclusions.

The Problem of Jonathan Stoddard Wightman’s Wife

The Puzzle

There are two men named Jonathan Stoddard Wightman in my family tree. One, who was born May 22, 1830, in Bristol, Hartford County, Connecticut, and died on September 9, 1893, in South Meriden, New Haven County, Connecticut. On April 26, 1855, he married Olive Fidelia Davis, born April 26, 1833 in Meriden, died March 13, 1903, in Southington, Hartford County, Connecticut, daughter of Zina and Amanda (Stevens) Davis. There’s work I could still do on this family, but I’m happy with what I have.

His parents were Elbridge M. Wightman, born about 1800 in Southington, died April 14, 1875 in Bristol. On June 17, 1829, in Bristol, he married Ursula Perkins, born 1812 in Southington, died August 7, 1889 in Bristol. She was the daughter of Elijah Mark Perkins and Polly Yale, who has an interesting line of her own.

The problem comes with Elbridge Wightman’s father, the first Jonathan Stoddard. He was born July 17, 1765 in Groton, New London County, Connecticut, and died April 18, 1816 in Southington. His second wife was Hannah Williams, who had married, first, Dr. John Hart of Southington.

His first wife, the mother of all but one of his children, is the unknown.

The Sources

- Wade C. Wightman, The Wightman Ancestry, including "George Wightman of Quidnessett, RI (1632 - 1721/2) and Descendants" by Mary Ross Whitman (Chelsea, MI: Bookcrafters, 1994), pp. 96-97.

- The American Genealogist, New Haven, Connecticut: D. L. Jacobus, 1937-. (Online database. AmericanAncestors.org. New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2009 - .), v. 25, Donald Lines Jacobus, "The ‘Other’ Gilletts” pp. 174-191.

- Bertha Bortle Beal Aldridge, Gillet, Gillett, Gillette families, including some of the descendants of the immigrants Jonathan Gillet and Nathan Gillet...also of the descendants of Barton Ezra Gillet, 1800-1955 (Victor, N.Y:, 1955), p. 25.

- Esther Gillett Latham, Genealogical data concerning the families of Gillet-Gillett-Gillette : chiefly pertaining to the descendants of Jonathan Gillet... (Somerville, Massachusetts:, 1953), 70.

- Lorraine Cook White, The Barbour collection of Connecticut town vital records (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Pub. Co., 1994), Colchester 103 (Gillett), Farmington 55-56 (Gillett).

- Ancestry.com. Connecticut, Church Record Abstracts, 1630-1920 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: 2013., Southington v107 p17, Gillet.

- Ancestry.com. Connecticut, Wills and Probate Records, 1609-1999 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015., Hartford Probate Records v1-3, pp196-197 Zachariah Gillet. Also Hartford Probate Packets, pp 916-933 Zachariah Gillet, and Hartford Probate Packets, pp 81-82, Nehemiah Gillet.

- Personal conversation with genealogist Gary Boyd Roberts of the New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

- Family notes of Elinor (Wightman) (Fredrickson) Fisher, 3rd great-granddaughter of the Jonathan Stoddard Wightman in question.

The Data

From Ellie Fisher’s Notes

Jonathan Stoddard Wightman’s first wife was Patty Hillet.

From the Wightman Ancestry

He married first, Mercy (Patty) Gillet, baptized 1768, daughter, probably, of Zachariah Gillet. (No date given, but their first child was born about 1789.)

From The ‘Other Gilletts’ TAG article

Donald Lines Jacobus presents an ancestral line from William Gillett of Somerset, England, through his son Jeremiah, ending with a daughter of Zachariah Gillett and his third wife, Sarah: Mercy, born at Southington, baptized September 4, 1768.

From Gillet, Gillett, Gillette Families

Bertha Bortle Beal Aldridge presents a different ancestral line from William Gillett of Somerset, this one through his son Jonathan, ending with a daughter of Nehemiah Gillet and his second wife, Martha Storrs: Martha, no dates given.

From Genealogical Data Concerning the Families of Gillet-Gillett-Gillette

Esther Gillett Latham presents the line through Jonathan and Nehemiah m. Martha Stoors, showing daughter Martha born April 12, 1767.

From the Barbour records

Colchester: Martha, daughter of Nehemiah and Martha, born April 12, 1767.

Farmington: several of Zachariah and Sarah’s children are listed, but several are missing, including Mercy.

Southington: there are no Gillets mentioned at all.

From Connecticut Church Record Abstracts

Records the baptism, on September 4, 1768, of Mercy Gillet, daughter of Zecheriah, in Southington.

From Connecticut Wills and Probate Records

Zachariah’s will, although it names Mercy as his daughter, mentions no married name for her. The will was written in November 1789. The probate papers show that she is still unmarried in March 1791. Also that Zachariah’s wife is named as Rhoda, and in March 1791 is known as Rhonda Frisbee.

Nehemiah’s will, written in July 1807, names his daughter Martha, still single at that time.

From a conversation with Gary Boyd Roberts

He mentioned that Jonathan Stoddard Wightman’s first wife was Martha Gillet.

The Questions

What was her name?

I respect personal information in the memory and records of family members, but am inclined to conclude that “Hillet” in the Ellie Fisher notes was, somewhere along the line, a misreading of “Gillet.” That settled, all sources agree on her last name. Her first name is a different story.

Ellie Fisher names her Patty; Wightman Ancestry has Mercy (Patty). According to the published lines from William Gillett, if her father is Zachariah, her name is Mercy; if he’s Nehemiah, she’s Martha. Unfortunately, both of these lines stop with Mercy/Martha; no marriage is recorded for either of them. But I have found no other reasonable suggestions for the parentage of Jonathan Stoddard Wightman’s wife.

In favor of the Nehemiah line (Martha): “Patty” is a common nickname for Martha, but uncommon for Mercy. My admiration for Gary Boyd Roberts as a genealogist is great, and he said her name was Martha. On the other hand, it was a very short, casual conversation and the information was off the top of his head, so I don’t want to rely too much on his memory.

In favor of the Zachariah line: The only printed source that records her marriage to Jonathan Stoddard Wightman (Wightman Ancestry) calls this line “probable” and mentions no other. But the most significant factor, I believe, is that this line places her in Southington (Hartford County), where all their children were born, whereas the other line is in Colchester (New London County).

When was she born? With the Nehemiah line, I have a birthdate: April 12, 1767. For the Zachariah line, there is only a baptism date: September 4, 1768. To say “about 1768” hedges my bets nicely.

When were Patty Gillet and Jonathan Stoddard Wightman married? Wightman Ancestry gives the birth of their first child as “about 1789” based on a death date of July 13, 1864 and an age at death of 75. This is consistent with census and gravestone data. Yet Zachariah’s probate records show Mercy as unmarried in March of 1791. (She signs her name “Mercy Gillet” and there is no mention of a husband.) Even if she was married that year, the timing is a little uncomfortable for the Zachariah line.

But the Nehemiah line is worse: Martha was still single when her father wrote his will in 1807, by which time all nine of J. S. Wightman’s children had been born.

Why didn’t these girls get married before their fathers wrote their wills? It would have made things so much clearer. But I think, after all, it is clear enough. The evidence of the wills, combined with the evidence of the location convinces me that Patty Gillet, wife of Jonathan Stoddard Wightman, was Mercy Gillet, daughter of Zachariah and Sarah Gillet of Southington.

One more question: What about Zachariah Gillet’s wives? Donald Lines Jacobus gives him three, the first two totally unknown, and the third known only as Sarah. Bizarrely, however, he claims that Zachariah’s will names his wife Sarah, whereas the wife in both copies I found of the will seems clearly to be “Rhoda.” Jacobus gives no death date for Sarah, but it’s a good assumption that she predeceased Zachariah, who married a fourth time. After Zachariah's death, Rhoda married someone named Frisbee.

I found a will for a Sarah Gillet, dated and probated in 1776, witnessed by Zachariah Gillet and Elizabeth Gillet. In this will, Sarah Gillet leaves everything she has to “my Nephu Sarah Andrus wife to Ichabod Andrus.” Sarah Gillet, daughter of Zachariah and his first wife, did marry Ichabod Andrus (Andrews). At first I thought this might be the will of Sarah, Zachariah’s wife. But Donald Lines Jacobus says it’s the will of Sarah, Zachariah's sister, daughter of Abner Gillet. That makes more sense, though I'm still confused by “nephu."

The Conclusions

Pending new evidence to confirm or debunk my conclusions, this is what I believe:

Jonathan Stoddard Wightman was born July 17, 1765 in Groton, New London County, Connecticut, and died April 18, 1816 in Southington, Hartford County, Connecticut. He married (1) Mercy (Patty) Gillet, born about 1768 in Southington, daughter of Zachariah and Sarah (surname unknown) Gillet. Jonathan married (2) Hannah Williams, widow of Dr. John Hart of Southington.

The ancestry of Zachariah Gillet, taken from “The ‘Other' Gillets” by Donald Lines Jacobus, published in The American Genealogist (see above), is, in an abbreviated form, as follows:

- The Reverend William Gillett, Rector of Chaffcombe, County Somerset, England.

- Jeremiah Gillett, born in England, emigrated to New England, lived in Wethersfield, Connecticut, and fought in the Pequot War of 1636-1638. Later he returned to England, but because of his service was granted land in Simsbury, most likely tended by his brother, Nathan of Simsbury until Jeremiah, Jr. arrived.

- Sergeant Jeremiah Gillett of Simsbury, Connecticut. He was probably born in England, about 1650, and he died in Simsbury on March 24, 1707/8.

- Abner Gillet, born perhaps 1684-88, died March 12, 1762 at Southington, Connecticut. He married, at Farmington, Connecticut, September 6, 1710, Mary Higginson, who was baptized at Farmington January 10, 1691/92 and died at Southington on February 8, 1766. She was the daughter of William and Sarah (Warner) Higginson.

- Zachariah Gillet, born at Farmington March 31, 1721, died at Southington in 1790. He married (1) at Southington, July 6, 1741, an unknown woman, (2) at Southington, April 3, 1750, another unknown woman who died September 1757, and (3) Sarah (surname unknown). According to my own conclusions, based on probate evidence, he also married (4) Rhoda (surname unknown) who later married someone named Frisbee.