At first I didn't participate in the "Me Too" campaign on Facebook (and elsewhere)—meant to reveal the magnitude of the problem of sexual harassment and assault in our country and now featured in Time magazine's "Person of the Year"—because, well, because I'm not a joiner, and I don't like chain letters, even if they don't promise me that blessings will come my way if I pass it on, and that misfortune is sure to follow if I don't.

Later, I thought it might not be such a bad idea to highlight a problem that has been ignored too long. Here's the Facebook exchange that started my thinking:

S: Me Too.

If all the women I know who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote "me too" as a status... and all the women they know... we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem.

Stop the silence. Stop the violence.

L: How do you define, "harassed"? There are days when I feel that being whistled at while walking down the street, or approached by a stranger trying to pick you up, is sexual harassment. And how about being kissed too familiarly by a drunk relative? "Felt up" by an overeager teenaged boyfriend at the movies? I could understand the last two being called assault, but I suspect many people wouldn't. At any rate, all of the above are unwelcome and ought to stop. But they are so many orders of magnitude below rape and other forms of what is clearly sexual assault, that I fear to muddy the waters and appear disrespectful of the pain of the latter victims. What is your take on this?

K: My view is this: any time one individual relates to another individual on an exclusively sexual plain, that individual demeans the other and diminishes their humanity. Although there are many degrees of disregard, the bottom line is that one person is being treated as something less than fully human. It's a way of thinking about people that is at the heart of sexism, racism, ageism, etc. As a human society we must insist on asserting the wrongness of that way of thinking. At school we define sexual harassment as any action of a sexualized nature that makes the target feel uncomfortable - from whistling to name calling to inappropriate touching to lifting someone's clothing and much more. It is important not to confuse harassment and assault. And important to distinguish what is legally prosecutable from what isn't. But we make too many excuses and allowances for behavior that is unacceptable. I think it is time to draw the lines about unacceptable behavior that falls short of rape far more clearly than we do.L: I think life has gotten a lot harder since the 1960's. I could certainly say "me too" to the definitions of harassment you've given. But nothing compared with what I hear from others ... and no worse than non-sexual harassment, which I would call plain rudeness.

That was helpful, but I wasn't convinced. I have friends who have to live with that kind of pressure in their work environment, or have actually been raped, and I didn't think it right to put my own experiences in the same category as theirs. Mine fell into the more general category of "bullying," though with a sexual dimension, because bullies will strike wherever they find a weakness. That, and "the guy was too drunk to know what he was doing, and would be mortified if he knew." It seemed like putting into the same category of "wounded in the war" both the man whose arm was nicked by a piece of shrapnel and the one who had both legs blown off. It's true, but is it helpful?

The broader definition of sexual harassment certainly cuts right to the heart of the problem, and goes along with what Jesus said about both lust and murder. But is it helpful to draw the line around all women, at least of a certain age, and quite a few men as well? Maybe—but I still didn't feel I could participate.

And then, today, I remembered.

I made the comment, in a discussion at choir rehearsal last Sunday, that one of our members, who teaches physical education, sure doesn't fit the stereotype of a female gym teacher. And I got to thinking about what I thought of as a stereotypical female gym teacher, and remembered the bane of my existence from high school.

I've repressed a lot of memories from high school gym class, and I won't name names because I really have managed to forget many of the details. But if the teachers, themselves, were not outright abusive (though it felt like it to me), the system that they participated in certainly was. I suspect it was not uncommon at the time, and it certainly never occurred to me that it was something I could successfully object to—it was just one of the many miserable things teachers were allowed to do to students.

And lest you be wondering what fearful revelations I'm about to make, I'll relieve your minds: It may even seem minor to you, and I don't think I bear any significant scars, other than those inflicted by gym class in general. But there's no doubt in my mind, looking back, that it was an abusive, even a sexually abusive, situation.

By the time we were in high school, we were required to take showers after gym class. I could see it for the guys, but we girls almost never perspired enough to need showers—and the process wouldn't have gotten us clean if we had. No doubt gym class has changed over the years; I certainly hope the bathing situation has.

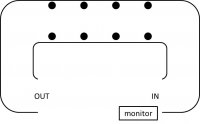

This is a rough plan of the shower room. Stripped naked, we were forced to give our names to a student monitor, who dutifully checked us off, then walk through a gauntlet of shower heads and out the exit. That's it. No soap—it slows down the line. In fact, the object was to run through as quickly as possible, minimizing our exposure to both water and the prying eyes of everyone else in the room. It was bad enough that we had to change into and out of our gym clothes in a public locker room, but the showers were an extra refinement of torture. Once a month we were allowed to avoid that humiliation, but that required us to announce to the monitor, and all within earshot, that we were having our periods.

This is a rough plan of the shower room. Stripped naked, we were forced to give our names to a student monitor, who dutifully checked us off, then walk through a gauntlet of shower heads and out the exit. That's it. No soap—it slows down the line. In fact, the object was to run through as quickly as possible, minimizing our exposure to both water and the prying eyes of everyone else in the room. It was bad enough that we had to change into and out of our gym clothes in a public locker room, but the showers were an extra refinement of torture. Once a month we were allowed to avoid that humiliation, but that required us to announce to the monitor, and all within earshot, that we were having our periods.

If our gym teachers had been male, no one would question that this situation was wrong. I fail to see that them being female made the forced exposure of our young bodies and private matters to their eyes and those of the entire class any more acceptable.

Age, and having gone through the process of giving birth to our children, have since made me less sensitive to what other people see and think, but I still appreciate the private changing areas that are now provided in public pools and gyms. No one—especially no pubescent child—should have to go through what I, and my classmates, endured.

So yes, "Me, too." It's insignificant compared to what others have experienced, but it's part of a pattern of disrespect that needs to end. Jesus had it right, you know. It's our heart attitude that matters. When we wink at smaller offenses, we promote an atmosphere in which heinous acts proliferate.

It's time for national repentance, and a good place to begin would be with the highest office in the land. If that's not forthcoming—a grassroots effort is probably better, anyway.

Yes. You got it. Me, too, but I don't want to publish the details.