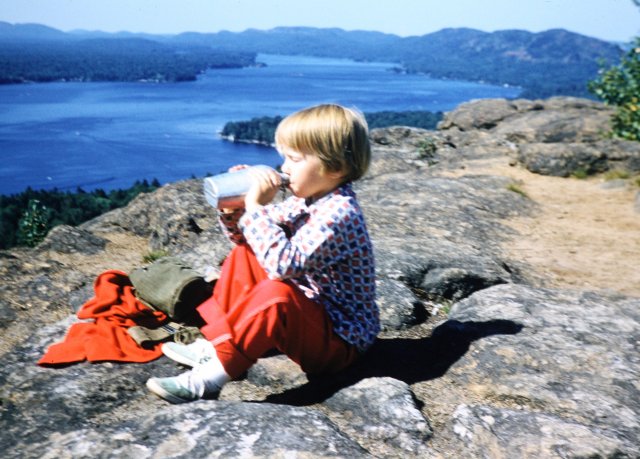

I grew up a conservationist. That's the kind of thing that happens when you live in the shadow of New York's Adirondack Mountains, and your father is a Boy Scout leader who loves camping and hiking, and frequently takes you mountain climbing with his buddies from work. "Forever Wild" gets in your blood.

From before I can remember, I knew how to respect the mountains, the waters, the flora, and the fauna. Dad wouldn't have it any other way. We subscribed to The Conservationist magazine, and treated the land and animals everywhere else properly as well. It's not surprising, then, that in my teenaged years I was drawn to what became known as the Environmentalist Movement.

That infatuation did not last, as the movement quickly moved beyond saving wild areas and animal habits, cleaning up air and water, and promoting responsible human encounters with nature. It became political, and extreme; it chose large-scale activism over human scale efforts; and it lost me.

All this flooded back to me when I read "Can American Conservation Survive ‘Green’ Energy?" It reminded me that someone said—it may have been Robert F. Kennedy Jr., for whom conservation is a critical issue, but I'm not certain—"The Democratic Party has focused its concern for the environment on one thing and one thing only: climate change. It is now the Republicans who are thinking about habitat destruction, species extinction, the destruction of the land, and our nation's food supply." I'm paraphrasing, of course, but that was the gist of it.

Thanks to our unique history of conservation and a culture of preservation, Americans have, for many decades, taken for granted their access to natural beauty.

Organizations ... founded by concerned citizens serve to champion habitat restoration and protection. Indeed, such was the very foundation of the modern environmental movement spawning nonprofits that advocate for policy, educate, install oyster beds, guard sea turtles, clean woodlands, “save the whales,” remind drone operators about the negative impacts of unmanned vehicles on wildlife, and, of course, constrain or prevent drilling and mining projects to preserve species and habitats.

But now the environmental movement is at odds with itself. The movement’s full-throated embrace of so-called “green energy,” successfully amplified by unprecedented government mandates and subsidies, is leading to habitat-invading and beauty-destroying energy projects at scales that not only rankle onlookers but also those environmentalists still committed to stewardship and conservation—and would shock the founders of the preservation movement.

In California, a 2,300-acre solar project requires destroying thousands of 150–200 year-old Joshua Trees, also the habitat of endangered desert tortoises. Locals object. Officials approve.

Disputes in Maine about where to put massive wind turbine projects pit environmental groups against conservationists intent on protecting wilderness and wildlife. Paradoxically, the state has the nation’s strictest mining laws, precluding any possibility of directly sourcing even a portion of the raw materials necessary to construct the turbines and solar panels slated for deployment to Maine’s electrical grid. [emphasis mine]

Meantime in Vermont a solar panel project that would cover 227 football fields of pristine landscape is being vigorously opposed.

‘Green’ energy policies come at the expense of far greater land and water use. [They] also ignore increased foreign resource dependence and environmental impacts overseas. The production of useful energy, which drives economic productivity, is always about tradeoffs. Americans are unlikely to tolerate increasingly obvious ‘green’ tradeoffs. [emphasis mine]

In addition to affordable cars, air conditioners, and smart phones, virtually all Americans want clean air and abundant, biodiverse seas and wide-open spaces our 19th-century forebearers helped to realize. You can bet future generations will too. It’s in our nature. And our energy policies and choices should reflect that.