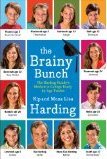

The Brainy Bunch by Kip and Mona Lisa Harding (Gallery Books, 2014)

The Brainy Bunch by Kip and Mona Lisa Harding (Gallery Books, 2014)

Facebook, like smartphones, can enslave or empower. Or both at once. At the moment I'm feeling grateful to Facebook, and the friend who posted a link that eventually led me to this Today Show feature about the Harding family and their book.

As most of you know, education has long been my passion, particularly the education of young children, and most especially my belief that most children can learn and do so very much more than we give them the opportunity to achieve. It will thus come as no surprise that when I heard of a family where seven (so far!) of the children had gone to to college by the time they were twelve years old, I immediately ordered the book from our library, and finished reading it the day after I picked it up. If read with an open mind, this is a book that can blow away a number of stereotypes and presuppositions, and not just about education.

Although a large number of homeschoolers are Christians, including many who have spectacular records both academically and socially, as the movement has grown there have slso been examples of less-than-stellar achievement, especially in academics. It is unfortunate that when many people think of "Christian homeschoolers," it is the latter example that comes to mind. The Harding family is a stunning counterexample, especially since The Brainy Bunch bristles with buzzwords that set off alarm bells: Mary Pride, A Full Quiver, Josh Harris, early marriage, Michael and Debi Pearl (at least they label the Pearls' book "a bit legalistic"), creationism, the Duggar Family, and others that might send some running for the hills. But hang on—they also mention John Taylor Gatto, Raymond and Dorothy Moore, unschooling, and the Colfaxes, quite on the opposite end of the spectrum (inexplicably leaving out John Holt, however). Mona Lisa and Kip sound like people after my own heart, able to take the best from many sources and leave aside what doesn't work for them. In any case, the family deals a clean blow to many prejudices, including that of the college student who once told them, "Children in big families have low IQs."

The Hardings insist, however, that their IQs are strictly average; their children are not geniuses. This bothered me at first, as it seemed almost a reverse boast, as if there were something wrong with being smart. But I think I know why they make this point, and it's important. There are a surprising number of people who have gone to college at an extremely young age (here's a list of the ten youngest), but they are generally prodigies with super-high IQs and extraordinary skills. This does nothing to encourage most families to believe that early college entrance is possible for their children. Or desirable. Despite its title, The Brainy Bunch shows that this higher-level work is well within the grasp of the average student, and why this is a good idea.

Some might even say the Hardings started out as a below-average family, or at least one with several strikes against it when it came to predicting their children's academic success. Kip and Mona Lisa were high school sweethearts who married in their teens. After high school, he went into the military and she started having babies. Lots of babies. Their life was not easy, requiring many moves, and times of great financial hardship. And yet here they are, with their children not only college graduates but successful at a young age in many fields: engineering, architecture, medicine, music, and more.

So how do they do it? The book may seem short on specific practical advice, because it's a lifestyle, not a curriculum. Here, however, is a brief timeline of their approach:

- Around age four we start to teach reading.

- By age six we start teaching borrowing, multiplying, writing short essays, and encouraging independent reading.

- By age eight we start algebra, reading real chapter books, and having the children do more writing on their own.

- By age ten they are figuring out what they really believe and why. They continue along in math as they add in reviewing for the SAT/ACT.

- Somewhere around age eleven, they have mastered the five-paragraph essay and can produce a decent research paper.

- By age twelve (sometimes sooner) they have finished lots of high school-level books on many general subjects to fill in their transcripts. With that and enough emotional intelligence, they should be ready for a college class or two.

Sixty-three sticky notes festoon the book, marking places I thought I might quote in this review, but I'll content myself with a few observations. Okay, several observations.

- I've read the complaint that the book is not well written. I see the point, but I've read a lot of popular books that are much worse, trust me. I would say it's not so much that it's poorly written as that the writing reminds me of blog-writing. It's not polished. But it's not bad; rather it's like the difference between folk music and a Bach fugue. Read it for what it is, and enjoy it.

- Most people's first reaction to this idea is, "Why not let your kids be kids?" It's a legitimate question, but as the Hardings point out, in many ways their children are allowed to be kids longer than most, since they are immersed in a loving family and don't have to face the pressures to "grow up" prematurely that are present in school.

- They make sure their children learn about creationism, but also about evolution. They encourage independent thinking.

- They are careful that their children read good books, and partake of quality television. They realize that the Internet can be a dangerous place, but liken it to a hot stove: it's a powerful tool that must be used wisely. ("The Internet wants to reveal all of Victoria's Secrets to your child. Teach them the real secret to success in life is to overcome temptation.") Once a child can use the Internet, the sky's the limit for learning, and parents can respond to questions with, "Go look it up and share with us what you learn."

- The book never mentions Project-Based Homeschooling, but there is a similarity in their methods. With the Hardings, however, it appears to be much less organized and purposeful.

- Conversations, especially at the dinner table, play a key role in the children's general education, and in sparking their interests. It reminds me of Richard Feynman's early education, given informally by his father in the form of questions and discussions on frequent, casual occasions. It also reminds me of a family we know; although they were never homeschoolers, they were always challenging their children with questions, and encouraging the children to do the same to their parents. Written like that it sounds unpleasant, but I observed it, and it was delightful, not at all like a test or a drill session.

- The Hardings were good at finding "back doors" when faced with locked front doors. When they lived in California, their children could obtain high school diplomas by taking a comprehensive test. They were nowhere near the age minimum to take the test, but there was a loophole: high school sophomores could take the test no matter what their age. Since the children were homeschooled and doing work on that level, the parents had no trouble classifying them as sophomores. That didn't work in Alabama, but they discovered that community college transfer credit made up for the lack of a diploma. They used lesser schools as stepping stones. Why not? At that age, they had plenty of time.

- The idea of sending a child to college at middle school age doesn't seem to jibe with their emphasis on family togetherness, but again this is the advantage of not aiming for the perfect college. The young students went to school close to home, in most cases living at home, and at first accompanied by one of their parents. When family needs forced them to be in different states, the children stayed with siblings or other relatives. As I recall, one child stayed in a dorm—at a somewhat older age—but the parents still managed to have plenty of contact and presence.

- Reading the descriptions of their efforts to keep their college kids close to family at all times rang a bell with me, and that's when it struck me: Mona Lisa Harding is a Hispanic mother. This would not have meant anything to me had our own children not attended a high school with a significant Hispanic population. Two characteristics marked Hispanic families, as far as I could tell: the importance of the Quinceañera celebration, and very tight parental reins kept on the girls, such as mothers accompanying their children on band trips, and a girl staying in the mother's hotel room rather than with the other students. Suddenly I recognized the Hardings' practices as typically cultural on the one hand, and extremely liberal on the other.

- They never say it in so many words, but I think the Hardings would agree with the idea that the middle and high school years are usually the most wasted time in a child's life. At that age they can and should be doing college-level work. Not MIT-level, but a lot more than is generally offered in middle school and high school. So they considered what it takes to get into college, and geared the children's early education to meet those requirements. The kids take none of the usual standardized tests, but begin preparing for the ACT and SAT instead. As soon as possible they begin taking classes for which they can get college credit.

- High priority is given to character education; there's no point in being academically advanced if your character development and social awareness are lacking.

- Since much emphasis is placed on the children's following their own interests, a big question is, How do you (or they) know what that is? By doing a lot of listening, and working together, for one thing. It's also important to note that the kids aren't deciding at age six what they want to do with the rest of their lives. Interests are never set in stone, but are allowed to change, going one way, then another. As long as learning is happening, the parents are happy.

- There's a lot of flexibility in the Hardings' program ("We follow more of a checklist than a timed schedule"), but here's a sample day:

- Get dressed

- Eat breakfast

- Chores

- Bible study

- ACT review (a section a day)

- Writing

- Lunch

- Reading (history and science)

- Math (if not covered in the ACT review)

- Spanish

- Violin or piano (they alternate)

- 2:30, ready or not, PLAY OUTSIDE!

- no homework "allowed" in the evenings—just reading for fun.

One of the reasons I read The Brainy Bunch was to know whether or not to recommend it to our children. I would say, most definitely. Would I buy the book? Not if I could get it out of the library. It's definitely worth reading, but I'd read it once before committing shelf space to it. Then I'd wait for the paperback to come out rather than paying over $16 for the hardcover. (Hint: it's available Interlibrary Loan in New Hampshire.) If I couldn't borrow it? It's under $10 for the Kindle version; I'd go for that.

Thanks for doing the legwork! Sadly, almost none of the college advice applies to life in Switzerland, but maybe we could send our kids to a college near their Florida grandparents when they are 12? Sounds like an interesting read, at least.

Thanks for reviewing this. I was made aware of them some time ago by my father-in-law and tried to "research" more details than were in the article he forwarded, but couldn't find much at the time. I hadn't stopped wondering about them, though; I was so fascinated by what little I did read about them! I didn't realize they had a book - great to know. Thanks again!

You're welcome, Sarah. Janet, your idea's a great one, but as another option, I think that what's available online will only become better and more useful by the time your kids are ready for college material. Even Joseph. :)

I don't think enough praise and gratitude can be given for the parents' value of education. What I see consistently today (in both homeschooled and public schooled children) is a lack of respect for both learning and the people who work to teach. There's a "we vs. they" mentality that does a lot of damage, that I've seen. I know a surprising number of homeschooled children who retain very little knowledge, because it's not valued or respected by their parents. As a child who loved being homeschooled, this continues to horrify me, so it's sometimes difficult for me to separate good practices from good parenting.

It makes me sad to hear of homeschoolers who don't value education. It's one reason I see the value in some sort of state check that homeschoolers are actually homeschooling. Mom, do you still believe the state should stay out of it? Too much oversight is a bad thing, but I'm afraid no oversight might mean the loss of the right to homeschool because some abuse it. Of course, I know Texas has the least oversight, and homeschoolers are doing well there . . .

Brenda and Janet, that's a tough issue. As I see it, there are two parts to it. One, as Janet pointed out, if there are too many bad apples there's the risk of a backlash that will endanger the very right to homeschool. That's not an insignificant concern. Two, we've already acknowledged the legitimacy of some government oversight to minimize abuses, from regulation of the meat industry to laws against assault, even of your wife or child in your own home.

The danger comes when that oversight gets out of hand—and how to define "out of hand." We make it illegal to starve a child, but not to force on him a vegan diet, or to allow him to drink soda for breakfast (though there are those who would make that illegal if they could). I welcome government inspection of meat that comes from industrial agriculture and large, chain stores, but think it's wrong to apply the one-size-fits-all regulations to small, local farmers and stores. I'd like to see government certification of raw milk (voluntary participation would be fine), because I don't have my own cow and don't know any dairy farmers. But I resent like crazy that the state of Florida has decided that raw milk should be illegal across the board.

I'm not against reasonable governmental oversight of homeschooling, but I'd rather an innocent-until-proven guilty approach, like Connecticut's. We don't schedule regular Department of Social Services inspections of everyone's home just to make sure the children aren't being beaten and are getting enough to eat. (At least not directly. Public schools, among other institutions, have become the eyes and arms of the DSS, which is one reason I think homeschooling is sometimes opposed.) So why should we require parents to prove to us that they are educating their children to our satisfaction? Especially when, despite all the fuss about standardized testing these days, there is no decent way for parents to hold schools accountable for satisfactorily educating their children.

I agree that it breaks my heart to see educational neglect, whether by schools or by parents. There are a lot of things that parents (and schools) allow that break my heart. But I wouldn't force my standards on them. One of my favorite Thomas Jefferson quotes is The care of every man’s soul belongs to himself. But what if he neglect the care of it? Well what if he neglect the care of his health or his estate, which would more nearly relate to the state. Will the magistrate make a law that he not be poor or sick? Laws provide against injury from others; but not from ourselves. God himself will not save men against their wills. And the care of children belongs to their parents. We can befriend, we can encourage, we can educate, we can show by example, we can provide resources ... but except in the most egregious situations, to assume that an impersonal, outside state knows better than parents how to raise their children is dangerous hubris.

That said, it is indeed appalling the number of people (parents, students, even educators) who don't value education enough to challenge each child to the height of his academic potential.

Full disclosure: I went to public schools exclusively until college (good ones, in two different states), and my parents were very much involved and valued education highly. Yet I didn't come close to my academic potential, and "retain very little knowledge" from my school experiences. Some, yes. But most of the knowledge that has stuck with me I learned from my parents, from books independently read, or from post-college experiences. There must be a better way.