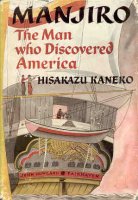

Manjiro: The Man who Discovered America by Hisakazu Kaneko (Riverside Press, 1956)

This book was apparently my paternal grandmother's: her name is scrawled with some other notes on the back of the dust jacket. I suspect it made its way to my bookshelves in one of the eight large boxes I took home when my father—a book lover indeed—moved out of our family home. Inspired by my 95 by 65 goal to read some of those books at last, I chose Manjiro to be my final book of 2015.

The only problem with this project is that I was hoping to declutter at the same time—but I keep finding such interesting books!

Manjiro was the impoverished, uneducated son of a Japanese widow, who by working on fishing boats helped his mother eke out a living. When he was 14, he was shipwrecked by a storm and rescued from a deserted island by an American whaling ship. Proving himself both bright and ambitious, he could have made a good life in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, the home of his rescuer and foster father. But Manjiro had dreams of helping his insular country open its doors to the wider world, and eventually made his way back home, not long before the arrival of Commodore Perry in 1853.

This book is not the only one written about Manjiro's experiences, but I love its style, which retains a feeling not only of 1950's America, but of Japanese culture as well.

There's more to the book than the quotes below, but I especially enjoyed his observations of mid-19th century America.

When he was invited by the Tokugawa Government, soon after Commodore Perry and his fleet appeared in the Bay of Uraga in 1853, he had a vital role to play for the wakening of the Japanese people to world civilization. Upon his arrival in Yedo, the former capital of Japan, he was examined by Magistrate Saemon Kawaji before he was officially taken into government service.

Answering the questions put to him by the investigating official, he revealed his own observations about America to the amazement of his listeners. Never can we overestimate the value of these observations which undoubtedly influenced the policy of the Tokugawa Government in favor of the opening of the country to foreign intercourse when Commodore Perry revisited Japan in February, 1854.

The next quotes are from Manjiro himself:

The country is generally blessed with a mild climate and it is rich in natural resources such as gold, silver, copper, iron, timber and other materials that are necessary for man's living. The land, being fertile, yields abundant crops of wheat, barley, com, beans and all sorts of vegetables, but rice is not grown there simply because they do not eat it.

Both men and women are generally good-looking but as they came from different countries of Europe, their features and the color of their eyes, hair and skin are not the same. They are usually tall in stature. They are by nature sturdy, vigorous, capable and warmhearted people. American women have quaint customs; for instance, some of them make a hole through the lobes of their ears and run a gold or silver ring through this hole as an ornament.

When a young man wants to marry, he looks for a young woman for himself, without asking a go-between to find one for him, as we do in Japan, and, if he succeeds in finding a suitable one, he asks her whether or not she is willing to marry him. If she says, "Yes," he tells her and his parents about it and then the young man and the young woman accompanied by their parents and friends go to church and ask the priest to perform the wedding ceremony. Then the priest asks the bridegroom, "Do you really want to have this young woman as your wife?" To which the young man says, "I do". Then the priest asks a similar question of the bride and when she says, "I do," he declares that they are man and wife. Afterward, cakes and refreshments are served and then the young man takes his bride on a pleasure trip.

Refined Americans generally do not touch liquor. Even if they do so they drink only a little, because they think that liquor makes men either lazy or quarrelsome. Vulgar Americans, however, drink just like Japanese, although drunkards are detested and despised. Even the whalers, who are hard drinkers while they are on a voyage, stop drinking once they are on shore. Moreover, the quality of liquor is inferior to Japanese sake, in spite of the fact that there are many kinds of liquor in America.

Americans invite a guest to a dinner at which fish, fowl and cakes are served, but to the best of my knowledge, a guest, however important he may be, is served with no liquor at all. He is often entertained with music instead when the dinner is over.

When a visitor enters the house he takes off his hat. They never bow to each other as politely as we do. The master of the house simply stretches out his right hand and the visitor also does the same and they shake hands with each other. While they exchange greetings, the master of the house invites the visitor to sit on a chair instead of the floor. As soon as business is over, the visitor takes leave of the house, because they do not want to waste time.

When a mother happens to have very little milk in her breasts to give her child, she gives of all things a cow's milk, as a substitute for a mother's milk. But it is true that no ill effect of this strange habit has been reported from any part of the country.

On every seventh day, people, high and low, stop their work and go to temple and keep their houses quiet, but on the other days they take pleasure by going into mountains and fields to hunt, while lower class Americans take their women to the seaside or hills and drink and bet and have a good time.

The temple is called church. The priest, who is an ordinary-looking man, has a wife and he even eats meat, unlike a Japanese priest. Even on the days of abstinence, he only refrains from eating animal meat and he does not hesitate to eat fowl or fish instead. The church is a big tower-looking building two or three hundred feet high. There is a large clock on the tower which tells the time. There is no image of Buddha inside this temple, where on every seventh day they worship what they call God who, in their faith, is the Creator of the World. There are many benches in the church on which people sit during the service. All the members of the church bring their Books to the service. The priest, on an elevated seat, tells his congregation to open the Book at such and such a place, and when this is done, the priest reads from the Book and he preaches the message of the text he has just read. The service over, they all leave the church. This kind of service is held also on board the ships.

Every year on the Fourth of July, they have a big celebration throughout the land in commemoration of a great victory of their country over England in a war which took place seventy-five years ago. On that day they display the weapons which they used in the war. They put on the uniforms, and armed with swords and guns, they put up sham fights and then parade the streets and make a great rejoicing on that day.

As the gun is regarded as the best weapon in America, they are well trained how to use it. When they go hunting they take small guns, but in war they use large guns since they are said to be more suitable for war. Ports and fortresses are protected by dozens of these large guns so that it would be extremely difficult to attack them successfully. Before Europeans came to America, the natives used bows and arrows, but these old-fashioned weapons proved quite powerless before firearms which were brought by Europeans. Now the bow and arrow has fallen into disuse in America. To the best of my knowledge, they have never used bamboo shields, as we do, although they use sometimes the shields of copper plates for the protection of the hull of a fighting ship. They are not well trained in swordsmanship or spearsmanship, however, so that in my opinion, in close fighting, a samurai could easily take on three Americans.

American men, even officials, do not carry swords as the samurai do. But when they go on a journey, even common men usually carry with them two or three pistols; their pistol is somewhat equivalent to the sword of a samurai. As I said before, their chief weapon is firearms and they are skillful in handling them. Moreover, as they have made a thorough study of the various weapons used by foreign armies, they believe that there are hardly any foreign weapons that can frighten them out of their wits.

More and more both fighting ships and merchant ships driven by the steam engine have been built of late in America. These steamships can be navigated in all directions irrespective of the current and wind and they can cover the distance of two hundred ri a day. The clever device with which these ships are built is something more than I can describe. While in America I had no chance to learn the trade of shipbuilding, so that I would not say that I can build one with confidence. Since I have looked at them carefully, however, I shall be able to direct our shipwrights to build one, if I could get hold of some foreign books on the subject.

While I was in America I did not hear any good or bad remarks in particular about our country but I did hear Americans say that the Japanese people were easily alarmed, even when they see a ship in distress approaching their shores for help, and how they shoot it on sight, when there was no real cause for alarm at all. I also heard them speak very highly of Japanese swords, which they believe that no other swords could possibly rival. I heard too that Yedo of Japan, together with Peking of China and London of England, are the three largest and finest cities of the world.

The book ends with a letter written to Manjiro's eldest son by U. S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt:

My dear Dr. Nakahama:

When Viscount Ishii was here in Washington he told me that you are living in Tokyo and we talked about your distinguished father.

You may not know that I am the grandson of Mr. Warren Delano of Fairhaven, who was part owner of the ship of Captain Whitfield which brought your father to Fairhaven. Your father lived, as I remembered it, at the house of Mr. Trippe, which was directly across the street from my grandfather's house, and when I was a boy, I well remember my grandfather telling me all about the little Japanese boy who went to school in Fairhaven and who went to church from time to time with the Delano family. I myself used to visit Fairhaven, and my mother's family still own the old house.

The name of Nakahama will always be remembered by my family, and I hope that if you or any of your family come to the United States that you will come to see us.

Believe me, my dear Dr. Nakahama,

Very sincerely yours,

FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT

The letter was written on June 8, 1933, just eight and a half years before our two countries would be fiercely at war.

Fascinating!