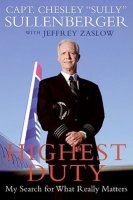

Highest Duty: My Search for What Really Matters, by Chesley "Sully" Sullenberger with Jeffrey Zaslow (William Morrow/HarperCollins, 2009)

Highest Duty: My Search for What Really Matters, by Chesley "Sully" Sullenberger with Jeffrey Zaslow (William Morrow/HarperCollins, 2009)

It's not often I like a movie better than the book it's based on (The Martian is the only one that comes immediately to mind), but in many ways that's true of the story of Captain Sullenberger's amazing landing of USAirways' Flight 1549 on the Hudson River. Sully, the movie, shows excellence of craftsmanship that's lacking in the book. Not surprising—Sullenberger is a pilot, not a writer. Nonetheless, Highest Duty is well worth reading and contains much important information not relevant to (and therefore not included in) the movie.

January 15, 2009. It's hard to realize how unconnected we were back then. We were caught up in our own lives—having just returned from our daughter's wedding in Switzerland—and I missed the event completely; at least, I have no memory of it. We owned a television set, but it was rarely turned on, and we were much more likely to be listening to CD's than to the radio. Porter was on the road, in Arizona I think, and while I'm sure he was aware of the incident, it didn't make the list of important topics to cover in our daily phone call. Today, I'm still pretty unconnected to news when it comes from television or radio, but if anything big happens, I can count on my friends on Facebook to start talking about it, and plenty of internet sources to flesh out their stories. I can (and frequently do) ignore the stories that are currently causing the world to buzz, but I can't miss them.

What I enjoyed most about Captain Sullenberger's story were the glimpses into what makes it possible for me to walk onto an airplane in one city and walk off, a few hours later, in another. These are woven in and out through the book, and the picture that emerges is both awe-inspiring and frightening. I've always felt safer in a plane than in a car, and statistically that's correct. Still, without feeling any less unsafe in a car, I'm a little more nervous about air travel than I was before reading Highest Duty.

People have incredibly high expectations for airline travel, and they should. But they don't always put the risks in perspective. Consider that more than thirty-seven thousand people died in auto accidents in the United States last year. That was about seven hundred a week, yet we never heard about most of those fatalities because they happened one or two at a time. Now imagine if seven hundred people were dying every week in airline accidents; the equivalent of a commercial jet crashing almost every day. The airports would be shut down and every airliner would be grounded.

Sullenberger is no complainer, and this is not the focus of his book. But the picture that emerges is of an airline industry in trouble, and I don't think it's gotten much better since 2009. He blames a lot on airline deregulation, but as I wrote in my previous post, the negative changes that have come to the airline industry are widespread throughout most industries and organizations. Some changes are technological, and many are societal.

A lot of people in the airline industry, and especially at my airline, US Airways, feel beaten down by circumstance. We've been hit by an economic tsunami. Some people feel their companies have held a gun to their heads, demanding concessions. We've been through pay cuts, givebacks, downsizing, layoffs. We're the working wounded.

People get tired of constantly fighting the same battles over and over again every day. The gate agent hasn't pulled the jetway up to the plane in time. The skycap is supposed to bring the wheelchair and hasn't. (I've helped more than a few older people into wheelchairs and pushed them into the terminal myself.) The caterer hasn't brought all the first-class meals. Catering companies always seem to be the lowest bidders with the highest employee turnover. At the end of a long day, you and your crew will get off the plane and make your way out of the terminal, but the hotel van isn't there when it's supposed to be.

All of this stuff beats you down. You get tired of constantly trying to correct what you corrected yesterday.

Many pilots and other airline workers feel that if they keep picking up all the slack, those who run the companies we work for will never staff the airlines properly, or do the training necessary, or hire the contractor who will be more responsible about bringing wheelchairs. And my Colleagues are right about that. In the cultures of some companies, management depends heavily on the innate goodness and professionalism of its employees to constantly compensate for systemic deficiencies, chronic understaffing, and substandard subcontractors.

At all airlines, there are many employees, including in management, who care deeply and try to make things better. But at some point, it can feel like a fine line between letting passengers fend for themselves and enabling the airline's inadequacies.

In my parents' generation, there was an unspoken agreement between big companies and their employees, at least at the level at which my father and his friends worked (somewhere between union workers and management): the employees would be hard-working and loyal, and the company would provide a decent salary, good benefits, a reasonable amount of job security, and a pension one could live on after retirement. That changed for my generation, and if the next generation seems deficient in the hard-work-and-loyalty department, it is good to remember that in their formative years many of them saw that the reward for such behavior looked an awful lot like betrayal.

It's fashionable to disparage "Millennials," by which most people seem to mean not people born between two specific years, but "the current crop of lazy young adults with no ambition, few skills, and a pathetic work ethic." Interestingly, the glimpse I have into the lives of actual people who would otherwise fit into that demographic shows them to be among the hardest-working and most dependable people I know, with very admirable skill sets. It is as if they are trying to make up for those who give the generation a bad name. And the bad apples do exist in high numbers, at least if my conversations with employers and teachers are accurate.

One young employee approached an evaluation convinced that she deserved a raise. When asked why, she responded not with a list of her accomplishments for the company, but with the assertion that she showed up for work every day. Which may be less astonishing than it sounds, given that her boss's complaint about the girl's co-workers was that they didn't show up much of the time.

Apparently the National Guard is authorized to send the police after its recruits that don't show up when expected. But in one town I heard about the Guard is trying to find another approach, since there aren't enough police to deal with the large numbers of no-shows.

Do you want someone with so little sense of responsibility sitting in the pilot's seat on your next flight?

Then there's the matter of experience. It is clear that what enabled Captain Sullenberger to take the actions that saved the life of every single person on board his airplane was a lifetime's worth of intense aviation experience. The older generation of pilots often had military backgrounds, and had put in an enormous number of flight hours before becoming commercial pilots. This included extensive training designed to hone their responses to dangerous, emergency situations. Military pilots still often transition to commercial piloting—I know a Southwest pilot who did just that—but with military cutbacks, civilian flight training is becoming more common, and pilots are graduating with many fewer hours of experience under their belts. Plus, I'm certain they don't get the kind of emergency experience the military pilots do: such training is dangerous—some pilots always die. The risk is necessary for the military, but can a civilian organization take those chances?

Technology, and the availability of simulators for training can probably do a lot to mitigate the situation. There is no substitute for real-life experience, but maybe pilots will do as well—or better—with a percentage of the hours done in the new forms of training. And automation can reduce some pilot error; we're told that in most situations driverless cars make better decisions than live drivers do. On the other hand, there are those other situations—the kind that leave you choosing to land in the middle of a river.

Automated airplanes with the highest technologies do not eliminate errors. They change the nature of the errors that are made. For example, in terms of navigational errors, automation enables pilots to make huge navigation errors very precisely.

Me? I'm not about to stop flying, but I'll do it with more respect and appreciation for those who make it possible. And I'm counting on those ambitious, talented, hard-working, and enthusiastic Millennials that I know are out there to continue to pick up the slack and do the right things. And then move into management and do the right things there, too.