Recasting the Past: The Middle Ages in Young Adult Literature by Rebecca Barnhouse (Boynton/Cook, 2000)

Recasting the Past: The Middle Ages in Young Adult Literature by Rebecca Barnhouse (Boynton/Cook, 2000)

This was another book from my son-in-law's wish list that I found intriguing. It turned out to be both disappointing and enlightening.

The disappointment was my own fault: The stated purpose of the book is "to provide teachers, librarians, and scholars of adolescent literature with a discussion of fiction set in the Middle Ages," so I should not have been surprised that the author talks like an educationist. Neither should I have been surprised (though I was) that the books she analyzes are all very modern. It reminds me of the fifth grade teacher who required that during their "free reading time," her students read only books from the Sunshine State Young Readers Awards list. This, she assured me, was because she wanted to make sure the children were reading quality books. Once I discovered that even to be nominated for that list a book had to be fiction and published withing the last three years, I knew why I was far less than impressed with the selection. I suppose modern authors need some support, but inflicting their works—to the exclusion of all others—on helpless students is even more unfair than forcing the students to eat school lunches.

This teacher-orientation and modern-author bias of Recasting the Past got my reading off on the wrong foot, but I was able to get over it because there really is some good information here. I've long known that much historical fiction, particularly for some reason that favored by schools (and popular movies), plays fast and loose with the facts. I figured the blame mainly fell on lazy authors, who had a story to tell and liked the idea of fitting it into an historical time period, but preferred to make the time fit the story rather than the other way around. Barnhouse opened my eyes to an entirely different source for the problem.

Although the author does not acknowledge this, I'm convinced that the base culprit is that there is such as thing as "young adult fiction." Why there should be is beyond my ken. Anyone who is mature enough to handle the subjects dealt with in these books—which include torture, religious doubts, and sexual activity—should be offended by dumbed-down reading levels and the assumption that everyone of a certain age must be interested in the same things.

Be that as it may, these are aimed at a young adult audience, and it shows. First and worst, the authors are apparently viewing their stories primarily as vehicles for teaching, and teaching 21st century values more than teaching history.

One such value is literacy. Barnhouse notes that much historical fiction aimed at schoolchildren is anachronistic in its attitude towards reading, writing, and book learning. No doubt they want to encourage the same in their modern readers, but it is wrong to give the impression that back then books were considered the key to knowledge, ignoring the practical ways knowledge was passed on in those times.

Modern authors also seem uncomfortable with allowing their young readers to experience attitudes not in line with 21st century standards. The young protagonists must be models of tolerance and diversity as defined by modern educationists; if anything negative is said about Jews, for example, it must come from the mouth of a character that the readers are not likely to like or respect. In a similarly unrealistic approach, Jews, Muslims, and generally anyone-but-Christians are treated by authors of much young adult fiction as paragons of virtue, instead of as human beings.

Barnhouse touches on other subjects, including stories that appear to be set in medieval times but actually belong in the Fantasy genre.

The primary use of his short book is for developing some tools for recognizing anachronism in so-called young adult fiction. Perhaps the most important of these tools is simply being aware of the problem.

Just two short quotes this time, emphasis mine:

The words "Middle Ages" imply a time between two eras, the Roman Empire and the rebirth of Roman culture in the Italian Renaissance. However, tell a twelfth-century Parisian scholar like Peter Abelard that Roman learning is dead and you'll get a surprised look—that is, if you can pry him away from his study of Greek and Roman historians and philosophers. Abelard and his contemporaries used the word modern to describe themselves. The big lie perpetrated by the Renaissance Italians, who said everything was dark and barbaric until they reinvented Rome, shows how little they knew about the transmission of thought, culture, and learning in the medieval period. While it's true that the vast majority of people didn't participate in all of this learning, neither did the majority of Romans. (Introduction, p xiii)

Well-told modern tales of the Middle Ages abound. ... The writers who research carefully enough to understand the differences between medieval and modern attitudes, between different medieval settings, and between fantasy and history, can help their readers understand a strange and distant culture: the Middle Ages. Writers who create memorable, sympathetic characters who retain authentically medieval values teach their audience more than those who condescend to readers by sanitizing the past. Trusting readers to comprehend cultural differences, presenting the Middle Ages accurately, and telling a good story results in compelling historical fiction, fiction that, like medieval literature in its ideal form, teaches as it delights. (p 86)

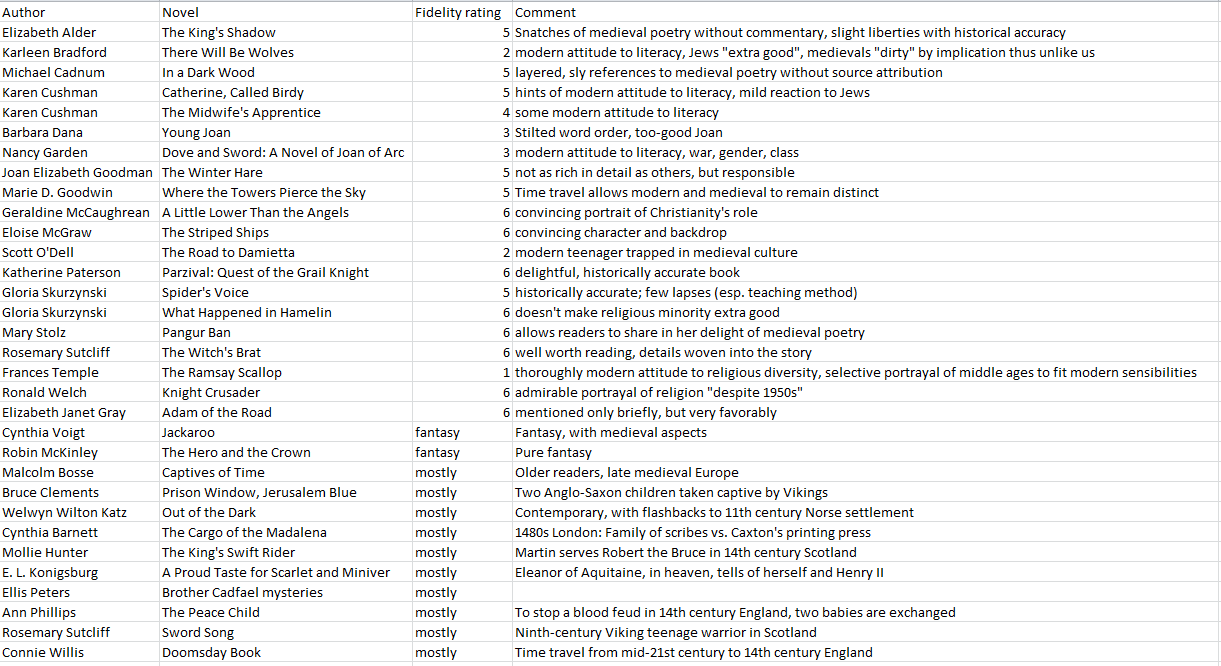

UPDATE 11/5/19 Here's a table from Stephan, summarizing the book's evaluations. Click to enlarge.

Stephan says, What might be confusing about the table is the multiple use of the comments column. The first books with a fidelity rating > 0 come with comments that summarize very briefly Mrs Barnhouse‘s critique; those with a rating = 0 with a „fantasy level“ comment; and the rest with a summary.

Does the book include a list of books that fit the "well-told" description?

Ask Stephan, who now has the book. As I recall, she mentions a few, but not many and mostly modern. The subject matter considered appropriate for teens is disappointing.

I've tried to summarize her short essays on different aspects of the medieval period and her evaluation of a set of books in light of some of these aspects by handing out a "fidelity rating" from 0 to 6, a higher number signifying higher fidelity to medieval culture. However, I'm unsure how to best get this little table into the blog comment, short of writing two dozen lines of html. Ask me if you want it.

Because she is looking at the use of medieval culture as a backdrop, the list of case studies is rather short (19 books, some getting pretty short shrift). Whether you think there are many "well-told" novels is dependent on perspective. She adds a list of further reading at the end, which comprises 10 books which "present, for the most part, historically accurate renderings of the medieval period."

If you take a screenshot of the table I can easily add it as an addendum to the post. I don't feel like writing the html either.