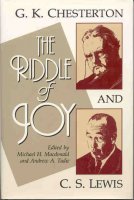

G. K. Chesterton and C. S. Lewis: The Riddle of Joy edited by Michael H. Macdonald and Andrew A. Tadie (Eerdmans, 1989)

This is an eclectic set of papers from the 1987 Conference to Celebrate the Achievement of G. K. Chesterton and C. S. Lewis in Seattle. As such, its effect ranged from fascinating me with new information—not easy, since I've nearly finished my 50-book C. S. Lewis retrospective—to reminding me why in college I stayed as far away as possible from the humanities and social sciences, especially philosophy and psychology.

Here are the paper titles and authors, with a few quotations when appropriate.

Some Personal Angles on Chesterton and Lewis (Christopher Derrick)

My heart sings within me whenever my jet leaves Heathrow for Kennedy (or Seattle/Tacoma), and one of the factors that cause it to sing is the prospect of far better and livelier conversation than I can easily find in foggy old England, even when other things are equal. That's the good news. The bad news—if I may say so, and even if I may not—is that the American mind does so frequently offer the response of a mere partisan ("Which side are you on?") when the response of a philosopher might have been more interesting. (p. 10)

[Lewis] was often invited to this country but never came: he once told me that he looked upon every such possibility with horror. The fact is that he knew practically nothing about the United States. His idea of this country came partly from Hollywood and partly from stories of the American wilderness, and as he very seldom went to the movies, even Hollywood's version of America was very imperfectly familiar to him. For the rest, it's symptomatic that when declining one invitation to the United States, he said: "Oh what a pity. To think that I might as your guest have seen bears, beavers, Indians, mountains." (pp. 10-11)

[Chesterton] had a remarkable talent for being simultaneously wrong about all the detailed particulars and resoundingly right about the question centrally at issue. That doesn't bother his confirmed admirers: they make allowances for it instinctively. But in general, it's unwise for a controversial writer to give an impression that he doesn't know what he's talking about, even in small matters. (p. 12)

That doesn't surprise me a bit: Chesterton was a journalist. I've seen plenty of newspaper articles and other media stories about situations I know personally, and in my experience all journalists get the detailed particulars wrong even when they are right in the overall impression.

If some present-day writer becomes hampered by this terrible worldwide shortage of semicolons, it's because Chesterton used them all up. (p. 12)

Not to worry. No one but me seems to like semicolons these days.

Lewis [is] amazingly deep and wide in his understanding of the human mind and of human behavior, and—to an astonishing degree in one who married so late and so strangely—of the female mind and female behavior in particular. (p. 14)

WHAT? WHAT? If there's one thing I've gathered from my extensive reading of and about Lewis, it's the impression that he knew nothing, nothing at all, about the female mind. Not unless women were almost a different species back in the mid-20th century England. The fact that someone writing in 1987 can commend Lewis for his understanding of women I find rather scary.

It's one thing to restate the old faith so as to make it more easily understood; it's quite another thing to modify the faith so as to make it more easily acceptable. There's a great deal of that going on.

Chesterton, the Wards, the Sheeds, and the Catholic Revival (Richard L. Purtill)

The decline [of the Catholic revival] began, I believe, when Catholics joined the fight against racial injustice and began deferring, for the very best of motives, to the black leaders in the movement, letting them set tone and strategy. It was certainly a dilemma; to insist on their Catholic motivations and foundations for objecting to racial injustice might have seemed to others in the movement to be separatist or patronizing: "I will help you in your struggle, but on my own terms, not yours." To avoid this predicament seemed to be an obvious good, but it set a dangerous precedent. When Catholics began getting involved in other movements, such as the peace movement, they fell victim to a pattern which I will call the "more revolutionary than thou" syndrome, by which in any revolutionary movement the extremists tend to take over on the pretense that anyone who is not as extreme as they are is a traitor to the movement. (p. 28)

This is a crucial warning to the Church today. I know someone who had an important message, well-researched and thought through, on the relations between men and women in the Church. If she had stopped there, I'm convinced she would have made a great difference among a group of Christians who really needed to hear what she had to say. However, her increasing radicalization, not only on this but on other issues, cut her off from them. She even lost me, and I have deep personal reasons for wanting that message to succeed.

C. S. Lewis and C. S. Lewises (Walter Hooper)

Lewis never said that A Grief Observed was autobiography, and he told me that it was not. ... It has been only in the last few years that people have been saying that [it] should be read as straight autobiography. ... C. S. Lewis the Doubter is the product of those who, over the last few years, have been trotting out the doubting passages of A Grief Observed and insisting that they are autobiographical. It is an attempt to persuade readers that Joy's death destroyed Lewis's certainty about the Christian faith. ... That is humbug. ... William Nicholson, who wrote the script of the film Shadowlands ... found it convenient for Lewis to fall to pieces when Joy died. ... When that film was first shown on the BBC, he wrote a piece making it clear that not a word of the dialogue he gave his characters was historical. ... Such close friends of Lewis's as his brother, Austin Farrer, Owen Barfield, and his parish priest, Gather R. E. Head, did not find Lewis behaving in the manner described. (pp. 47-48)

There was a similar problem with Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer. Despite Lewis's insistence that it was fiction, a vehicle for raising and discussing questions about prayer, it was hard to scotch the idea that these were real letters sent to a real person.

The Legendary Chesterton (Ian Boyd)

[Chesterton] was one of the liberals whom Orthodox Catholics feared, but he was also one of the Catholic Christians whom the liberals persecuted. In his own person he seemed to include a genial friendliness to apparently irreconcilably hostile points of view, and yet he also vigorously opposed any attempt to tone down or to compromise strongly held views. (p. 61)

The Prayer Life of C. S. Lewis (James M. Houston)

Never would [Lewis] recommend saying one's prayers last thing at night. "No one in his senses, if he has any power of ordering his own day, would reserve his chief prayers for bed-time—obviously the worst possible hour for any action which needs concentration."

[Quoting one of Lewis's letters] Oddly enough, the week-end journeys (to and from Cambridge) are no trouble at all. I find myself perfectly content in a slow train that crawls through green fields stopping at every station. Just because the service is slow and therefore in most people's eyes bad, these trains are almost empty—I get through a lot of reading and sometimes say my prayers. A solitary train journey I find quite excellent for this purpose. (p. 73)

Looking Backward: C. S. Lewis's Literary Achievement at Forty Years' Perspective (Thomas T. Howard)

Heaven knows, if I were running the world of graduate English studies, almost everything that is required reading nowadays would be destroyed in an immense book burning, and Lewis would be made required reading. (p. 91)

G. K. Chesterton and Max Beerbohm (William Blissett)

The Centrality of Perelandra to Lewis's Theology (Evan K. Gibson)

G. K. Chesterton, the Disreputable Victorian (Alzina Stone Dale)

Chesterton came to disbelieve in progress because "real development is not leaving things behind, as on a road, but drawing life from them, as from a root." (p. 146)

G. K. Chesterton and C. S. Lewis: The Men and Their Times (John David Burton)

[Quoting Lewis] I believe man is happier ... if he has a freeborn mind.... I doubt whether he can have this without economic independence, which the new society is abolishing. Economic independence allows an education not controlled by government, and in adult life it is the man who needs, and asks, nothing of Government who can criticise its acts and snap his fingers at its idealogy. (p. 167)

The Chesterbelloc and Modern Sociopolitical Criticism (Jay P. Corrin)

Regardless of how well planned and intelligently administered, Chesterton and Belloc were convinced that massive reforming schemes imposed from above via the engines of the state could never achieve lasting success. They insisted that lasting reform would need popular support, commitment to change among ordinary people being necessary from a moral and practical standpoint. Reform from above was wrong because it would stifle creativity and remove the common people from positions of responsibility for their own affairs. Initiating and carrying out reform from outside the community also would have an enervating effect on democracy itself, since the state would be taking the initiative in areas of local concern. Furthermore, collectivism contributed to the construction of big, bureaucratic government which could potentially exercise totalitarian control over its citizens. (p. 177)

For Chesterton, the state was no more than a human contrivance to protect the family as the most fundamental of social mechanisms, and, in his opinion, the integrity of this important vehicle of primary socialization could best be protected by the state's guarantee of private property, which Chesterton recognized as the mainspring of liberty and the source of creativity. (p. 178)

The major objectives of the Distributist movement were the restoration of self-sufficient agriculture based on small holdings, the revival of small businesses, and the transfer of management and ownership of industry to workers.

Long before 1945, Parliament had ceased to be the supreme governing body in Britain. It subordinated itself to the managerial powers of the state's bureaucratic apparatus. (p. 185)

The dilemma for Distributists was that they worked to maximize the individual's liberty, but the majority of people have persistently preferred the security of a fixed income, a guaranteed job, and health care to the risks associated with self-employment. (pp. 189-190)

Chesterton in Debate with Blatchford: The Development of a Controversialist (David J. Dooley)

C. S. Lewis: Some Keys to His Effectiveness (Lyle W. Dorsett)

The Sweet Grace of Reason: The Apologetics of G. K. Chesterton (Kent R. Hill)

[Quoting Chesterton] Thomas Aquinas understands what so many defenders of orthodoxy will not understand. It is no good to tell an atheist that he is an atheist; or to charge a denier of immortality with the infamy of denying it; or to imagine that one can force an opponent to admit he is wrong, by proving that he is wrong on somebody else's principles, but not on his own. ... We must either not argue with a man at all, or we must argue on his grounds and not ours. (p. 235)

[Quoting Chesterton] Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about. All democrats object to men being disqualified by the accident of birth. Democracy tells us not to neglect a good man's opinion, even if he is our groom; tradition asks us not to neglect a good man's opinion, even if he is our father. (p. 238)

C. S. Lewis's Argument from Desire (Peter J. Kreeft)

God can be avoided. All we need do is embrace "vanity of vanities" instead. It is a fool's bargain, of course: Everything is exchanged for Nothing—a trade even the Boston Red Sox are not fool enough to make. (p. 255)

Of course I had to look it up: Yes, Peter Kreeft lives in Boston.

Derrida Meets Father Brown: Chestertonian "Deconstruction" and that Harlequin "Joy" (Janet Blumberg Knedlik)

I just have to say that this is the most bizarre of all the papers. The author is an English professor, which surprised me. I thought only philosophers were that detached from reality.

The Psychology of Conversion in Chesterton's and Lewis's Autobiographies (David Leigh)

This one isn't much better, but at least it's relatively short. The truth is, I found the last three papers difficult to get through. Much of the book is worthwhile, however.

The comment about Chesterton getting the details wrong reminds of a description of one eminent mathematician: "His theorems are all correct, but his lemmas are often false."

Someday maybe you could do a post on the three (or five, or most important, or...) things you have learned from C.S. Lewis?!

I'll take that as a challenge for the completion of my Restrospective, Eric!