It all depends on whose ox is being gored....

I first became aware of how much a U.S. president can do by executive order when Barack Obama made such lavish use of that power. Mr. Obama's supporters were quick to point out that he was hardly the first president to do so.

President Trump is doing the same, and the complaints are now on the other side.

Me? I don't want anyone's ox to be gored. The fact that one president's executive orders can be undone by the next president only shows why legislation ought to be done by ... the Legislature. You want change to happen, make it work through Congress. Is that too difficult? Maybe there's a reason—maybe it should be hard. If you're trying to accomplish something that half the country is against, maybe you need to rethink and rework and renegotiate.

There's a reason some religious denominations wait for full agreement before making major decisions. There's a reason a jury's verdict must be unanimous.

I'll grant that agreement on anything by everyone is impossible in a country as diverse and cantankerous as ours, but moving forward on important policies without the support of a healthy majority—and without provision for the protection of the minority—is death for a democracy.

"It's my ball now, and we'll play by my rules" isn't working very well, and it's making a lot of people unhappy.

Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead by Brené Brown (Gotham Books, 2012)

Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead by Brené Brown (Gotham Books, 2012)

It's possible that Brené Brown's message is as important as that of Gordon Neufeld in Hold On to Your Kids. I'm not ready to say that yet, but I can tell that her work is too important to be missed. I can also say that I would love to see Neufeld and Brown in the same room, discussing their theories. Although they come from different fields and perspectives, when it comes to the problem of peer-orientation (though Brown never mentions the subject) and what children need from their families, I'm sure they'd be substantially in agreement.

Normally I prefer my information in written form, preferably in a book with all its potential for logical organization and corroborating detail, but aside from some tantalizing hints on the Blue Ocean Families blog (from the home page, search for "Brené" to find some references to her work), my best introduction to Brené Brown came from some videos. Here are several to choose from.

The Power of Vulnerability (20 minutes) The TED talk that put Brené Brown on the map.

There's more, including at least two more Chase Jarvis LIVE interviews that I haven't listened to yet because, well, because they're 90 minutes long. Start with the TED talks.

The only warning I have to give is that Brown's language is not exactly SFG (safe for grandchildren), either in the talks or in her books. It's not all that bad, by modern standards; such language is so common I've gotten used to it somewhat. I do wonder why people feel they have to talk that way, but that's another issue. I definitely recommend that you not let it make you avoid Brené Brown's work.

Now to the book. Daring Greatly is only one of Brown's books, not the oldest and not the most recent—merely the first that was easily available at our library. I had my struggles with it, but that won't stop me from reading the others as I can. I believe a good deal of my struggle was similar to one I had with Hold On to Your Kids. Maybe it's generational, maybe it's because I avoided social sciences and humanities as much as possible when I was in school. Whatever the cause, these people keep using words that I think I know, but which they endow with specialized meanings. It's confusing. It reminds me of the old creeping vs. crawling problem:

Everyone knows that babies first start creeping along the floor, then crawl on their hands and knees, then walk. That's the normal progression. But not to people in the child development and physical therapy fields, for whom "crawling" is on the belly, and "creeping" on hands and knees. In their professions, they know exactly what they are talking about, but it sure confuses the rest of us.

So here. She has specific interpretations of "shame," "guilt," "vulnerability" and more terms that are essential to her discoveries. I'm glad I watched the videos first.

I also struggled with integrating her ideas with my Christian beliefs. Brown makes no apology for being an Episcopalian, but her work is entirely secular. That's not a bad thing: most of the discoveries in this world have universal application, and a secular approach makes them available to far more people. Again, it's a matter of language. Cognate words can help one understand a foreign language, but there are also false cognates, and it all must be sorted through. Her descriptions of love, acceptance and belonging due to our position rather than to our deserving is a very Christian message, but for someone as steeped as I am in the horrors of the sin of pride and in the need to put others before ourselves, her points about self-care, self-worthiness, and treating ourselves well require some wrestling. I totally get the airlines' message to put on one's own oxygen mask before assisting others, and I'm properly horrified that I frequently (read: all the time) say cruel things to myself that I hope never to say to someone I love—but it still requires working through.

There's a lot that requires working through in Brené Brown's ideas. I'm sure I could benefit much from her books, a blank notebook, and a long stretch of solitude. But this is a review, not a confession, and the book goes back to the library soon. I'm not even clear enough to summarize her points, but with the videos above, and the quotes below, you can begin your own journey. (The bolded emphasis in the quotations is mine.)

Brown quotes Lynne Twist’s The Soul of Money, on scarcity.

“For me, and for many of us, our first waking thought of the day is ‘I didn’t get enough sleep.’ The next is ‘I don’t have enough time.‘ Whether true or not, that thought of not enough occurs to us automatically before we even think to question or examine it. We spend most of the hours and the days of our lives hearing, explaining, complaining, or worrying about what we don’t have enough of…. Before we even sit up in bed, before our feet touch the floor we’re already inadequate, already behind, already losing, already lacking something. And by the time we go to bed at night, our minds are racing with a litany of what we didn’t get, or didn’t get done, that day….”

In a culture of deep scarcity—of never feeling safe, certain, and sure enough—joy can feel like a setup. We wake up in the morning and think, Work is going well. Everyone in the family is healthy. No major crises are happening. The house is still standing. I’m working out and feeling good. … This is bad. This is really bad. Disaster must be lurking right around the corner.

Over the past decade, I’ve witnessed major shifts in the zeitgeist of our country. … The world has never been an easy place, but the past decade has been traumatic for so many people that it’s made changes in our culture. From 9/11, multiple wars, and the recession, to catastrophic natural disasters and the increase in random violence and school shootings, we’ve survived and are surviving events that have torn at our sense of safety with such force that we’ve experienced them as trauma even if we weren’t directly involved.

My reaction, when I read this, is that this is crazy. We are so much better off than most of the world, for most of history. However, as I wrote in my Good Friday post, if our personal suffering is overall less, our vicarious suffering is off-the-charts worse. Brown acknowledges this later on:

Most of us have a stockpile of terrible images that we can pull from at the instant we’re grappling with vulnerability. I often ask audience members to raise their hands if they’ve seen a graphically violent image in the past week. About twenty percent of the audience normally raises their hands. Then I reframe the question: “Raise your hand if you’ve watched the news, CSI, NCIS, Law & Order, Bones, or any other crime show on TV.” At this point about eighty to ninety percent of the audience hands go up.

I define vulnerability as uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure.

Among some folks it’s almost as if enthusiasm and engagement have become a sign of gullibility. Being too excited or invested makes you lame.

Vulnerability is based on mutuality and requires boundaries and trust. ... We can’t always have guarantees in place before we risk sharing; however, we don’t bare our souls the first time we meet someone. We don’t lead with “Hi, my name is Brené, and here’s my darkest struggle.” … [S]haring appropriately, with boundaries, means sharing with people with whom we’ve developed relationships .... The result of this mutually respectful vulnerability is increased connection, trust, and engagement.

Churches make this mistake a lot, trying to force community like a hothouse bloom, rushing the process through unearned intimacy.

You can’t use vulnerability … to fast-forward a relationship.... When it comes to vulnerability, connectivity means sharing our stories with people who have earned the right to hear them—people with whom we’ve cultivated relationships that can bear the weight of our story. Is there trust? Is there mutual empathy? Is there reciprocal sharing? Can we ask for what we need? These are the crucial connection questions.

Here’s one strategy Brown uses for coming out of what she calls a shame attack:

[I talk] to myself the way I would talk to someone I really love and whom I’m trying to comfort in the midst of a meltdown: You’re okay. You’re human—we all make mistakes. I’ve got your back. Normally during a shame attack we talk to ourselves in ways we would NEVER talk to people we love and respect.

[W]e have to be willing to give ourselves a break and appreciate the beauty of our cracks or imperfections. To be kinder and gentler with ourselves and each other. To talk to ourselves the same way we’d talk to someone we care about.

Shaming someone we love around vulnerability is the most serious of all security breaches. Even if we apologize, we’ve done serious damage because we’ve demonstrated our willingness to use sacred information as a weapon.

Feeling disconnected can be a normal part of life and relationships, but when coupled with the shame of believing that we’re disconnected because we’re not worthy of connection, it creates a pain that we want to numb.

When the people we love or with whom we have a deep connection stop caring, stop paying attention, stop investing, and stop fighting for the relationship, trust begins to slip away and hurt starts seeping in.

The two most powerful forms of connection are love and belonging—they are both irreducible needs of men, women, and children. As I conducted my interviews, I realized that only one thing separated the men and women who felt a deep sense of love and belonging from the people who seemed to be struggling for it. That one thing was the belief in their worthiness. It’s as simple and complicated as this: If we want to fully experience love and belonging, we must believe that we are worthy of love and belonging.

Belonging is the innate human desire to be part of something larger than us. Because this yearning is so primal, we often try to acquire it by fitting in and by seeking approval, which are not only hollow substitutes for belonging, but often barriers to it. Because true belonging only happens when we present our authentic, imperfect selves to the world, our sense of belonging can never be greater than our level of self-acceptance.

[As parents we] don’t have to be perfect, just engaged and committed to aligning values with action.

What’s ironic (or perhaps natural) is that research tells us that we judge people in areas where we’re vulnerable to shame, especially picking folks who are doing worse than we’re doing. If I feel good about my parenting, I have no interest in judging other people’s choices. If I feel good about my body, I don’t go around making fun of other people’s weight or appearance.

When we obsess over our parenting choices to the extent that most of us do, and then see someone else making different choices, we often perceive that difference as direct criticism of how we are parenting.

Wholehearted parenting is not having it all figured out and passing it down—it’s learning and exploring together. And trust me, there are times when my children are way ahead of me on the journey, either waiting for me or reaching back to pull me along.

It’s easy to put up a straw man … and say, “So we’re just supposed to ignore parents who are abusing their children?” Fact: That someone is making different choices from us doesn’t in itself constitute abuse. If there’s real abuse happening, by all means, call the police. If not, we shouldn’t call it abuse. As a social worker who spent a year interning at Child Protective Services, I have little tolerance for debates that casually use the terms abuse and neglect to scare or belittle parents who are simply doing things that we judge as wrong, different, or bad.

Worthiness is about love and belonging, and one of the best ways to show our children that our love for them is unconditional is to make sure they know they belong in our families. I know that sounds strange, but it’s a very powerful and at times heart-wrenching issue for children.

Engagement means investing time and energy. It means sitting down with our children and understanding their worlds, their interests, and their stories. Engaged parents can be found on both sides of all of the controversial parenting debates. They come from different values, traditions, and cultures. What they share is practicing the values. What they seem to share is a philosophy of “I’m not perfect and I’m not always right, but I’m here, open, paying attention, loving you, and fully engaged.”

What do parents experience as the most vulnerable and bravest thing that they do in their efforts to raise Wholehearted children? I thought it would take days to figure it out, but as I looked over the field notes, the answer was obvious: letting their children struggle and experience adversity.

I used to struggle with letting go and allowing my children to find their own way, but something that I learned in the research dramatically changed my perspective and I no longer see rescuing and intervening as unhelpful, I now think about it as dangerous. … Here’s why: Hope is a function of struggle.

Hope is learned! …[C]hildren most often learn hope from their parents. To learn hopefulness, children need relationships that are characterized by boundaries, consistency, and support. Children with high levels of hopefulness have experience with adversity. They’ve been given the opportunity to struggle and in doing that they learn how to believe in themselves.

If we’re always following our children into the arena, hushing the critics, and assuring their victory, they’ll never learn that they have the ability to dare greatly on their own.

I explained [to my daughter] that I had spent many years never trying anything that I wasn’t already good at doing, and how those choices almost made me forget what it feels like to be brave. I said, “Sometimes the bravest and most important thing you can do is just show up.”

Real bloggers include guest posts now and then, right? It's time I moved up in the world. Not, however, by acquiescing to those who e-mail me at the blog address requesting to be invited as a guest poster on my "great blog"—by which they mean they want to use my platform to advertise whatever they're selling. Instead, this post fell into my lap in the form of an e-mail from my friend SW. In response to a recent post, in which I brought back my Good Friday post from a few years ago, All the Sorrows of the World, she shared something she had written in her own journal several months ago. It was not a reply to my post, being written completely independently, but it was such a perfect and sane response to the problem I asked if I might publish here writings here. She graciously consented.

I was trying to self-analyze why going online makes me feel anxious and overwhelmed. It didn't take long to come to the conclusion that it's because, for me, being connected to the whole world feels like a weight I'm incapable of bearing. I read all the hurts, the reasons to fear, the foolishness, the hate, etc., and I think, "It's too much!" My desire to retreat from it actually proves to me that I am a sane person, because of two facts:

- I am taking it seriously. I know that every story—even if it's laced with half-truths and some misinformation—involves real, living people. People not as unlike myself as we'd all like to think. And so, naturally, my heart goes out to them. Sometimes I pray for them. But I still feel pretty helpless, because out of the half-dozen stories I read, I may be able to donate help to one, but there will be a new batch tomorrow morning, tomorrow evening, the next day, and the next...which leads into,

- If any of us would stop and be honest for just one cotton-pickin' moment, we'd admit that it really IS ALL TOO MUCH. It's insanely too much hurt, too much heartache, too much innocence lost, too much cruelty, too much evil, and, frankly, just too much to wade through if we are actually reading thoughtfully and giving a damn about every human being represented in those stories.

Well, the truth is, God didn't make me able to handle the weight of the world. And in my case personally, when I try, I fail to "handle with care" the FEW burdens He DID give me to carry: my husband, my kids, my close family, my actual (not virtual) friends...actually, I have my hands FULL when I think about all the dear souls whom God has gifted to my care, who are authentically in my circle of influence. If I decide to try to carry the weight of the world on my shoulders, the ones I actually owe my attention to will get dropped. I mean, I don't know about you, but my time, my emotional energy, and my financial resources are all finite. I start jumping on the Internet bandwagons and there is less of my time, my emotional energy, and my limited material resources to go around (not saying we shouldn't donate, but seriously, my kids wear shoes so tattered Goodwill couldn't sell them—we're not exactly out of balance in how we spend our money). Mostly, mentally, I get caught up in the "out there" and am far less present in the "here and now" where the needs around me are.

I think the world actually would go around better if more people could give most of their attention to the small but very real, very vital, circle of people (not things) God has given them the privilege of caring for. For me, in this season, it's my husband and kids. But it could be aging parents. Mentally challenged siblings. The refugee family next door. Co-workers. A new widow. Count up about a dozen—or even only a half-dozen—and if I, we, were to really invest our all into THEM, we'd have our hands, heads, and hearts full.

I wish I could solve the problems of the world, but very, very rarely am I a part of any solution simply by informing myself of them. It's a weight I am not equipped nor designed to carry. In other words, God doesn't expect me to have the capacity to "love the whole world." (Only He has that capacity, and He did, and He does. John 3:16.) But my own little circle? I can handle that...I can love them. I can love them well. God told us to "love one another." He gave me that much. So that much I ought to do. Why fail Him in the small area of faithfulness He's given me by claiming "The world is so big, and has so many problems!" I can love well the few I HAVE, and teach them to love well the few they have, who may in turn love well the few they have. I guess that's just me, but I'd rather die knowing I was faithful to the ones God gave ME, rather than attempting (and failing!) to love every person spread across the face of the earth, including the ones who needed me most.

Thank you, SW. Please stop by with another guest post sometime. :)

Permalink | Read 2008 times | Comments (2)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Looking to Jesus, the founder and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross, despising the shame, and is seated at the right hand of the throne of God.

This is the time of year when Christians make special recognition of Jesus' suffering, death, and resurrection. I love Holy Week services, from Palm Sunday to Easter and everything in between. Due to extraordinary (but good) circumstances, we missed our Taizé (Monday), Stations of the Cross (Tuesday), Tennebrae (Wednesday), and Easter Vigil (Saturday) services this year. Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday, and Good Friday services were nonetheless a good preparation for Easter.

Somewhere in the middle of it all, I began to ask myself, What does Jesus think of the events leading up to Easter? Not our church services, but the actual events, from his triumphal entry into Jerusalem, through his agonizing in the Garden of Gesthemene, his last Passover with his disciples, his betrayal, trial, and crucifixion, and that mysterious time between death and resurrection. What does he think of it all? I don't mean then, while he was going through it, but now. Looking back, if that has any meaning in his case.

I asked myself this question because I was thinking about childbirth. Yes, I realize how ridiculous it is to compare the pains of childbirth to those of crucifixion, let alone the mental, emotional, and spiritual agony of all the sins and sorrows of the world, but bear with me here.

Setting aside the great difference in scale, I think there are important parallels. In each case, there is pain, anguish, fear, physical and mental exhaustion, and reaching the point where you just know you can't go on any longer, followed by the unimaginable, unsurpassable thrill of victory, of success, of achievement—and the birth of something new, wondrous, and beautiful.

Most mothers I know like to exchange birth stories, in all their glorious and grisly detail. Those are "then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars" moments. But the toil and pain are remembered, not relived. We tell these "war stories" because we are justifiably taking credit for our part in the miracle. The pain has been crowned and glorified by its accomplishment.

Nor do we regale our children with the horrors of what it cost us for them to exist, at least not if we're psychologically healthy ourselves. If our child were to start to focus on the pain of childbirth, we would quickly tell him, "You're missing the whole point. Sure, it was a difficult process, but it was worth it. What matters is not the suffering, not the effort. What matters is that you were born! The pain is in the past, and our family is immeasurably greater because of it. The whole world is greater because you are here. That is the point. Be thankful for what I did for you, but don't dwell on it. Focus on using your uniqueness to be the best person you can be, to bless the family—and the world—you were born into. That, not your grief at my sufferings, nor even your gratitude for them, is what makes me happy and overwhelmingly glad to have endured them. Go—live with joy the life I have given you!"

So I wonder. Is it possible that Jesus has similar thoughts?

It's good to be reminded of the events that birthed our post-Easter world, and not to take lightly the suffering that made it possible. However, some people, many preachers, and even a few filmmakers appear to take delight in portraying Christ's agony in the most excruciating (consider the etymology of that word!) detail possible, even, like the medieval flagellants, attempting to participate in it. Even less extreme evangelists and theologians spend more ink and energy on Jesus' death than on his resurrection.

Could it be that Jesus looks back at that time with joy, knowing that he accomplished something difficult, important, and wonderful? Is it possible that he sometimes looks at us and thinks, You're missing the whole point? That it would rejoice his heart if we thought less about his death and more about how to use the new life he has given us?

Go—rejoice—live!

Permalink | Read 1985 times | Comments (2)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Hallelujah! Christ is risen! He was OBSERVED by many in his resurrected state.

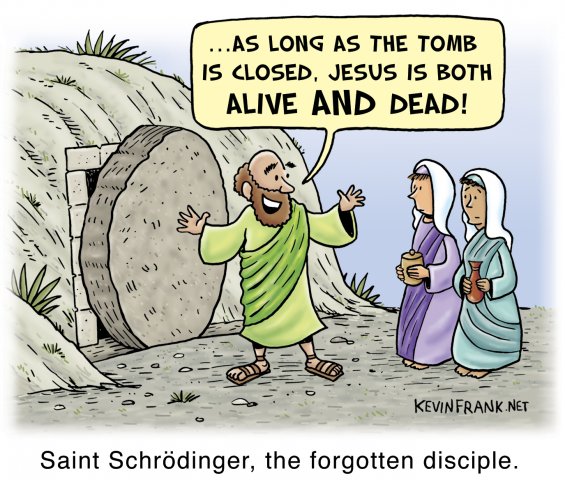

My serious Easter post is still half written, but thanks to my cousin Stephanie, who shared this from kevinfrank.net, I can give you an Easter chuckle to accompany your Easter joy.

Permalink | Read 1970 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I'm bringing back my Good Friday post from four years ago, because I think it's worth bringing to mind again.

Good Friday.

Remembering the day all the sorrows of the world (and then some) were in some incomprehensible way taken on by the only one who (as fully both divine and human) could effectively bear them—albeit with unimaginable suffering.

I trust it is in keeping with the holiness of the day, and not in any way disrespectful or unmindful of its significance, to consider that as we, in the West at least, pay less and less attention to the significance of Good Friday, we find ourselves taking all the sorrows of the world on ourselves—and being crushed by them.

Consider the lives of our ancestors throughout almost all of history: Most of them were born, died, and lived their entire lives in the same small community. Even when they migrated, were taken captive, were exiled, or went to war, for all but a handful, their circle of experience remained small and local.

Our ancestors suffered greatly. The unbearable sorrow of losing a child was not uncommon. There was no easy divorce to sever marriages and blend families—but death played the same role. The lack of sanitation, antibiotics, immunizations, and even a simple aspirin tablet made for disease, pain, and death on a scale most of us can’t imagine. Starvation was often only a bad harvest away. Slavery and slave-like conditions were taken for granted for most of history. I’m not here to minimize the sufferings of the past.

But there is a very important however to their story. Their pain was on a scale that was local and human. They suffered, their families suffered, and their neighbors suffered. Travellers might bring back tales of tragedy far away, but that was a secondary, filtered experience.

And today? The suffering in our close, personal circles may indeed be less. But our vicarious suffering is off the charts. Whether it’s a murder across town, a kidnapping across the country, or a natural disaster halfway around the world, we hear about it. In graphic, gory detail. Over and over we hear the wailing and see the shattered bodies. Full color, high definition, surround sound.

If that were not enough, our television shows and movies flood us daily, repeatedly, with simulated violence and horror, deliberately fashioned to be more realistic than life, so that, for example, we become less the observers of a murder than the victim—or the murderer himself. (Not to let books off the hook, especially the more graphic and horrific ones, but their effect is somewhat limited by the imagination of the reader.)

No one imagines that the death of a stranger half a world away, much less in a scene we know is fictional, is as traumatic as a death "close and personal." But a few hundred years of such vicarious suffering is not enough to reprogram the primitive parts of our brains not to kick into high gear with horror, anguish, and above all, fear. Our bodies are flooded with stress hormones, and our minds tricked into believing danger and disaster are much more common than they are. We repeatedly make bad personal and national decisions based on events, such as school shootings and kidnappings by strangers, that are statistically so rare that the perpetrators cannot be profiled. We hear a mother wailing for her lost child, and our soul imagines it is our own child who has died. We watch film footage of an earthquake and shudder when a tractor-trailer rolls by. Did anyone see Hitchcock’s Psycho and enter the shower the next morning without a second thought?

Worse still, for these sorrows and dangers we can’t even have the satisfaction of a physical response. We can’t fight, we can’t fly, we can’t hug a grieving widow; no matter how loudly we shout, Janet Leigh doesn’t hear us when we warn her not to step into the shower. Writing a check to a relief organization may be a good thing, but it doesn’t fool brain systems that have been around a whole lot longer than checks. Or relief organizations.

I don’t have a solution to what seems to be an intractable problem, although a good deal less media exposure would be a great place to start.

The human body, mind, and spirit are not capable of bearing all the griefs that now assault us. We are not God.

Permalink | Read 1817 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I've never aspired to be a leader. I learned that in elementary school, when my parents and teacher were talking about "leadership qualities" and I thought, "Doesn't sound like fun to me." I don't mean I necessarily like to be a follower—mostly I like to do my own thing (child of the '60s) and other people can come along, or not, as they wish.

But a man at our church, who died not long ago, is making me rethink the idea of leadership. I barely knew him, but our choir sang for his funeral, and what I learned about him then made me wish I had found a way to cultivate his friendship.

He was accomplished enough for 10 people. He graduated in Mechanical and Electrical Engineering from Princeton. He was a marine, serving in World War II and Korea. He followed that up by working for the CIA, earning the highest possible award for valor. For three years he endured Communist prison camp in Cuba. His civilian life achievements and community activities are too numerous to mention.

And they played bagpipes at his funeral.

Most amazing of all for someone so distinguished, everyone who knew him remarked about his humility. Churches talk a lot about "servant leadership" but apparently this man actually embodied it. He was, indeed, a "humble servant."

And yet....

The other thing said about him was that people did things the way he thought they ought to be done. He was humble, he was gentle, he was soft-spoken—but you didn't cross him. Somehow, he induced people to see things his way without pushing them around, without exerting his power—which is real power, indeed.

What might the world be like with more leaders like that?

Permalink | Read 2267 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

When she was in fifth grade, Heather won her school's spelling bee. It was a significant accomplishment—the competition was stiff—and we were proud of her.

Imagine how Edith Fuller's parents feel. The homeschooled five-year-old from Oklahama won the regional championship spelling bee and on May 30 will be competing in Scripps National Spelling Bee in Washington, DC. The contest is for children through eighth grade. Here she is in action.

This Slate article takes a positive, if somewhat mocking tone, but asks, Why?

Spelling bees have a certain poignancy that, say, a science fair lacks. Being a good speller is like having beautiful handwriting or being an excellent seamstress: It’s impressive, but it’s almost totally unnecessary for most 21st-century adults. If STEM is the future, spelling feels like the past.

To which I must respond, Why basketball? Why golf? Why the Olympics? If the significance of spelling bees, and of spelling as a skill, are questioned "in the age of spell-check," what's the point of knowing knowing how to throw a javelin or to jump long and high in these days when we don't need to hunt for our food and escape cave bears?

It's possible to overdo anything, of course, and not everyone will find it worthwhile to attain Olympic or spelling bee champion status. But developing the mind and body is its own justification.

Homegrown Hollywood: Searching for Family in All the Wrong Places showed up this morning in my Weekly Genealogist magazine. It's a short and sweet story of a woman's efforts to learn about the grandmother she never knew. I'm linking to it here because it epitomizes what our country so desperately needs.

A writer from Los Angeles travels to a small town in North Carolina and meets a distant cousin who might as well live on a different planet for all they have in common ... on the surface.

She welcomed us with a warm drawl and a tight hug. We sat on her couch as she told us stories and pulled out pictures. The longer we stayed, the happier I felt and something calmed inside of me.

The author wasn't the only one who'd had doubts about the cultural differences.

"Let me tell you, honey," she drawled in her thick accent. "I was nervous about meeting ya'll, but as soon as I saw you I thought, 'now there is blood kin.' And then everything was different."

The key to healing our fractured nation is real people. Not stereotypes, not Hollywood depictions, not news stories, but real, physical people who have families and serve dinners and smile at strangers.

She was right. Everything was different.

I had been trying to reach my grandma through gravestones and houses and hats I'd put on in a dusty old attic.

But where I'd actually found her was in people like Shelvie Jean.

Hope for healing lies outside our bubbles.

Our church publishes a little booklet every Lent, comprising short meditations on chosen Bible verses, done by members of the congregation. This year, when they asked for volunteers, I signed up. Part of the reason was the challenge of saying something meaningful in 100 words. As you will see, I exceeded that slightly—but was still within the boundaries. April 3rd was my day, so I'm publishing it here as well.

Romans 9:33: and the one who trusts in him will never be put to shame

These words occur several times in the Bible, in both the Old and New Testaments. "Him" refers to the Messiah in the Old, identified with Jesus Christ in the New. In context and in combination they portray Jesus as a rock that can be a secure foundation or a stumbling block. The characteristics that make rock a good base on which to build also make it painful and costly to ignore as we walk along.

"Never be put to shame" is also translated as “not make haste, not be disturbed, not panic, not worry, not be disappointed.” If Jesus is the foundation of our lives, there is no need to worry or make frantic efforts. Our responsibility is to do our work with calm confidence: God has our backs.

What was remarkable, for me, was how I accomplished the project. It may not seem like much to those of you who can whip off such things easily, but trust me, my usual approach to such assignments has always been (1) put it on the shelf because the deadline is comfortably far off, (2) periodically think to myself, "oh, yes, I need to get that done," (3) forget about it entirely, and (4) remember at the 11th hour, panic, drop everything else, and stay up late to finish the job, with the dissatisfaction of knowing I could have done better.

However, this time the scenario went like this:

I received my assignment on Tuesday. I took a quick look at the context of the verse excerpt, then laid the task aside, keeping it in my mind and prayers as I did other things.

During the day I found a few moments here and there to look up information about the verse and make a few notes. (Hooray for the Internet.) I continued to think in the background and pray.

Wednesday I sat down and wrote my thoughts. This was the longest part, but it wasn't hard because I had done the legwork already. Saying what I want the way I want to always takes time, but it flowed well, which was a good thing because Wednesday was a very busy day. I finished it Wednesday night after choir and still got to bed on time.

Thursday morning I reread it, made a couple of minor tweaks, and sent it off—earning commendations for being the first to return my meditation, three weeks in advance of the deadline.

It's a small victory, but gives me hope that eventually I'll figure out how to make it spill over into the rest of my life. You know, the "do my work with calm confidence" part!

Permalink | Read 1885 times | Comments (2)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]