My Big Adventure of the week? Picking up two books I had ordered from the library. I called ahead because they have a 25% capacity limit, and was informed that they haven't come close to the limit since they reopened. The checkout workers were masked and behind a plexiglas shield far more extensive than those at Publix, which I view as inadequate for the protection of the grocery clerks. On the same trip, I stopped at the post office to check our PO box. We're that wild and crazy around here.

The next trip didn't really count, since we encountered no breathing creature but merely picked up a pair of new masks from a friend's porch. Behold, the Space Grace Face Mask!

How does this mask differ from our other Grace Mask? It's pleated, surgical mask style, instead of the Fu design. I like the Fu for its fitted nose area, but this does it one better by having an aluminum strip sewn into it, which can be used to conform the mask to the nose. This is a great improvement in fit, and results in significantly less air being expelled through the top (and fogging my glasses).

The earpieces are elastic, rather than crocheted, which also helps with the fit, thanks to the elastic finally having become available for purchase. I wanted the mask a little tighter, and putting a simple twist into the elastic on each side did the trick. I could make the fix permanent with a few stitches, but this was so easy and worked so well I may just leave the size flexibility built in.

Based on my limited experience at this point, I'd say this is the most comfortable of my masks, largely because it feels the most secure. The aluminum nosepiece is a significant addition, I think. I might even be able to sing in this mask, albeit in a most muffled manner, without it slipping out of place. Thanks, Grace!

Sadly, this mask does not have the non-woven interfacing layer of our other masks, which I believe provides significantly more filtration, because the interfacing is still unattainable. On the plus side, the lack of the interfacing layer does make breathing easier, so that on my most recent trip to the grocery store I did not find myself experiencing the reflexive deep breathing that troubled me before. Hopefully this, along with the better fit, will make up for the lack.

About that grocery trip. On the list of COVID-19 blessings surely must be my new habit of doing my grocery shopping at 7 a.m. on Saturday. The roads were empty, the parking lot nearly so. There were far more Publix employees to deal with than customers. It almost makes grocery shopping fun. Almost.

I'm afraid some people may be becoming complacent, however, as I did see a couple of folks without masks. As I've said before, it's not that I have that much faith in the protective power of the mask, but it does say that the wearer is concerned and trying to be careful. It reminds me of Michael Pollan's observation that nutritional supplements have been shown not to do any good at all for normal people, but nonetheless, people who take supplements are generally healthier than those who don't, because of related habits. "Be the kind of person who takes supplements," he advises, "and ditch the supplements." Well, I'm not ready to ditch the mask—but you get the idea. And I certainly think that the time when we are beginning to experiment with reopening is a time to be more cautious in other behaviors, not less.

There was a little bit of toilet paper available, but no napkins this time. (Last week the situation was reversed.) Flour was nearly unavailable, unless you wanted the self-rising variety. I almost bought one of the four or five all-purpose bags, but decided to leave them for someone else because our home supply is still okay.

If there'd been plenty of flour I would have bought a couple of bags. I like to bake under normal circumstances, and find that I have joined the rest of the country in upping my efforts during this time. Decluttering and baking seem to be the new national pastimes. Our New Hampshire family went through their 50-pound bag of King Arthur White Whole Wheat flour in one month. (There are a lot of bakers in that family. And even more eaters. Well, maybe not that. I believe they all bake.)

Porter's big outing for the week was finally getting his much-postponed census-taker's fingerprinting session taken care of. In case you were concerned, he passed the background check. :)

Permalink | Read 1403 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

On April 1 I mailed two things to Switzerland: a birthday card for Janet, and a Priority Mail box of books that she had ordered and had had delivered here, because she was planning to be here in April to receive them.

Perhaps mailing an important package on April Fools' Day was not the wisest choice this year.

Normally both items would have been delivered within a week, but what with the great reduction in flights from here to Europe, I was not surprised that the package was slow, even though it was sent Priority Mail. It did go promptly to Miami; on April 2 tracking results showed that it had been processed there and was "now on its way to the destination."

And there the status sat. Where the package itself sat I know not. Most likely it was at the Miami airport in some big pile awaiting an airplane to take it across the Atlantic, but for all I know it could have been sitting in a pile at Swiss Customs, because their system, too, was affected by the COVID-19 disruptions.

The days passed. The weeks passed. April turned into May, and as far as the USPS was concerned, the package was still "processed through Miami and on its way to the destination."

An then, on May 19, Janet reported the arrival of her birthday card! I'd had no idea that it also had been delayed. Frustrating as that was, it gave me hope, and I shelved the "lost mail" report I had been about to submit.

Six days later, the missing package cleared Swiss Customs, and was delivered the next day. The package and its contents were in fine shape.

Fifty-six days it took for those books to make the journey from Orlando to Switzerland. And yet I feel more gratitude than consternation, even though I paid airmail prices for slow-boat service. It's a reminder of how much normal international communication has changed since the days when transporting packages to far-away countries routinely took several months.

Permalink | Read 1198 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Florida's gradual "reopening" has had little discernable effect on our lives. None of our outside activities have reopened as yet, and we are enjoying life at home. Publix has discontinued its "senior only" hours, which initially disappointed me, but it turns out that 7 a.m. is a great time for shopping anyway, and Saturday morning even better than during the week. There were even fewer shoppers than there had been during the senior hours.

My Saturday shopping trip was made even easier by this article sent to me by our EMT son-in-law. (Hmmm. That does not look right at all. Our son-in-law is not "empty," which is what that sounds like when I read it. He is an Emergency Medical Technician.) The most salient point:

There’s no evidence to suggest that COVID-19 can spread through food, or what it’s wrapped in, Dr. Stephen Hahn, commissioner of the US Food and Drug Administration, said Thursday.

Although the virus can last for up to several days, depending on the surface, apparently the "viral load" is low enough for groceries not to be a concern. That just cut my grocery shopping time in half!

Well, not quite. I've developed such an efficient system of unpacking and "detoxifying" my groceries that I decided, as a beginning, to continue the procedure where it was easy, and forget about it when it was not. Start small, as they say. It still made a big difference in the stress level.

And how are the store shelves looking, you ask? Much like before, with most shelves normal but with some unexpected surprises. For two weeks in a row now, toilet paper has been once again unavailable, after it had looked to be permanently back. Flour is still scarce. Three weeks ago there was no flour of any brand on the shelves; last week and this there were a few bags of Pillsbury and Gold Medal all-purpose flour, so I did something I probably haven't done in decades: bought non-King Arthur flour. I find myself surprised by the run on flour. If forcing people to stay home is causing a resurgence of bread-and-cookie-baking, I consider that a positive consequence.

There is now plenty of milk (and the price has gone down), and eggs. This is not, however, evidence that the country has suddenly gone vegan: hot dogs and bacon are popular enough be be rationed.

That's about all there is to report. Life goes on, and blessings abound. In many ways I'm going to miss this "holding pattern" when it comes time to deal with so many things that I've had an excuse to put off.

Permalink | Read 1323 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The new coronavirus has brought many changes to our lives. I do not think that we’ll ever go back to the way things used to be, as I once hoped. I think that there will be a new normal. What might that look like? Many things are changing. I believe that there are three things that could really change and do both good and bad things for us.

The first thing is education, and colleges in particular. College, in my opinion, has been suffering from having too many people that go there to continue high school, have some parties, and delay their entry into having to be responsible. Now, I have not been to college, but I have looked at some, and the fact that the “party scene” is an actual rating is somewhat disturbing. Also, because the government subsidizes college loans, almost everyone goes to college, which drives down the value of a college degree. The last and most important thing is the invention of the Internet. This puts all the information of the world at anybody’s fingertips. If you can sift through false information, then you hardly need to go into debt for the better part of your life just so you can learn from an “accredited” source. Think about math. You can only lie so much about math on the Internet. So, why do you need a professor? You might have to work harder to do it on your own, but it is a lot cheaper.

These problems were all there before coronavirus hit. But it has brought them to the light. With distance learning, people are realizing that they are getting only slightly better or more formal education than watching a YouTube video. They don’t get to talk to the professor, and they don’t get the party life. Some people are thriving in this environment. Some are not. This shows that college is itself not required for learning. Only the information is, regardless of the source. Academia is a powerful force, but I think the world will awaken to the reality of higher education eventually, perhaps sooner than we think.

Education is also changing at the lower levels. Distance learning looks as if it is going to eradicate snow days in New Hampshire, as that will be used instead of giving the students a day off.

This pandemic has been good for some things. It is forcing families to spend time together again. Previous to this, the family had been declining, to the detriment of Western Civilization. Almost 50% of families look at homeschooling more favorably now, according to some polls. Many of these families have found out about the greatest, most important secret that is kept: the intelligence of the U.S. is going down. We are a far cry from teaching algebra in fifth grade, as they did in the 1800’s. Now, it is a nasty secret that nearly 14% of American young adults are “functionally illiterate,” according to the National Center for Education Statistics. This covers people who are “able to locate easily identifiable information in short, commonplace prose text, but nothing more advanced.” This information once more comes from the National Center of Education Statistics. This is a travesty. The school system encourages it, because you can’t fail. This is the secret. No matter how bad you do, you cannot fail. You might have to do summer school, you might have special education courses, but you can’t fail.

This is where distance learning is showing that some kids can thrive in the homeschool environment. That is to say, where they can sit at a desk, alone, listen to music, and work without having to worry about anything but themselves. Some people need the social interaction, but those that don’t are going to have a rude awakening when they come back and return to the bustle, and the tediously long school days. I never could figure out how public schools make school last so long.

That’s one thing that could change. The education system will change forever I think, and for the better. However, watch out for the colleges to release their “studies” disenchanting people with homeschool. They have already started, Harvard deriding the “religious extremists” and the “non-socially conforming people” that are homeschoolers. If people want to pull out of the system, the system will not let go easily. If people leave the schools, they will learn that they can learn everything on the Internet. If they do that, they will be disenchanted with colleges. This is not what colleges want. So they will fight.

Another thing that will change is Main Street. I shouldn’t say that it is changing, because main street small businesses were already declining. But, they are going to fall significantly now. I think that business will barely be able to survive economically due to the shutdown. But for those that do, who will go? Why go to the local department store to risk exposure to COVID when you could order from Home Depot? Why go to the bookstore or the clothes store, when you can order from Amazon? Soon, I think, the main street businesses will have to innovate, or they will have to go extinct, eliminating a memory that, while I have never lived, seems to be one of people knowing people in their town, and much more of the economy staying inside the town. It sounds like a good memory to me.

Amazon will grow. I know my family's Amazon orders have not gone down. If anything, they’ve gone up, as anything we can get from there, we get, rather than going to the local stores. And it’s usually cheaper, too. Amazon is reaching critical mass. They are either going to become a power, or the government is going to break them up. Amazon does good things for the people. No Amazon agents came up to our door and made us purchase Amazon, we bought stuff from them freely. We got them because they are cheaper, and more convenient. So, is Amazon growing a bad thing? They have been paying people well in this pandemic, engendering loyalty to the company. Amazon has cut out the middle man of UPS and FedEx, and now delivers its own products. Soon, we’ll have drones delivering our packages. A natural monopoly is not a bad thing. If a company doesn’t have government benefits, and simply beats its competitors, then it is a good thing. It must keep its prices low in order to keep competition from springing up. That is good. I think that an Amazon natural monopoly is better than the government taxing it to death. Because if the government taxes it, Amazon’s prices must go up. Therefore, a tax on Amazon is a tax on all the people who purchase Amazon goods. I think that Amazon growing and Main Street declining is good for the economy, though it may not be good for the culture.

The culture will change. How people communicate with each other will change. I have not had a conversation with anyone outside of my family face to face since mid-March. That is two whole months. And yet I still play games with people, and still have lots of communication. I don’t want to give up face to face communication, but I can’t speak for the rest of my generation. Why do things with people you don’t agree with in town when you can find someone who perfectly matches your interests on the other side of the U.S.? The world may change and move towards this. The decline of Main Street and the changing of education both encourage this.

No one can predict how the world will change. I certainly can’t. I leave the information to you to sort out. There will be changes, some good and some bad. The world is always changing, sometimes slowly and sometimes quickly. We all have the power to change our world, though it be like a raging river at times. Throw a rock in a river, and it alters the currents. Enough rocks, in the right places, and a whirlpool is bound to form.

Permalink | Read 1560 times | Comments (1)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Guest Posts: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

A friend sent me this interview, from the Indianapolis Star, about our current situation. The interviewees were two area residents, each 102 years old. Clearly they've seen a lot. Here are a couple of their responses that I found particularly interesting.

Did your parents ever talk about what it was like to have a newborn [during the Spanish flu pandemic]?

I don't think they talked to me that way. They didn't talk much politics at home. They just put their head down ... and went ahead and worked and scraped and tried to keep food on the table.

What were your concerns [about polio] as a parent?

We all were worried but didn’t talk about it; it wasn’t blown up like this virus is.

Just like we would be now, when there's no vaccine. You were helpless. You just hoped for the best. ... I don't think we were organized enough to do anything (like this). The government didn't step in and do anything for you.

But my absolute favorite part of the interview came in the interviewer's reaction to one lady's suggestion for ways to save money based on her Depression-era experiences (emphasis mine).

To save money, the little things add up. Roush has always washed Ziploc bags, for instance.

To which my reaction, as well as that of the friend who sent me the article, was, "Is she suggesting that most people don't wash and reuse their Ziploc bags?"

Permalink | Read 1662 times | Comments (2)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Conservationist Living: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

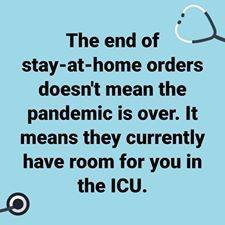

A friend posted this on Facebook. I have my suspicions that it was meant—by him, by the original author, or both—to be snarky, but it nonetheless expresses an important truth: The goal of social distancing and other protective orders is not to eliminate the virus nor the risk, but to slow down the spread so that our medical system can handle those who will need help.

COVID-19 is a virus that most of us will have to face, and it doesn't surprise me at all that cases are up as restrictions are eased. That's part of the process and must eventually happen. But it's important to remember that it's like going back to eating after a bout of the stomach flu. You need hydration and nutrition if you want to get well, but if you move straight away to eating as you normally do, you will start the vomiting cycle all over again. You have to start slowly and carefully and base your next move on how well your body handled the previous one.

There is no way for me to say whether or not our restrictions are being eased too soon. Even with the stomach flu there's a lot of trial and error involved, and we know a lot more about stomach bugs than about COVID-19. That the restrictions must be eased and eventually lifted is clear. I get quite frustrated with those who insist that doing so is sacrificing people's lives to the god Mammon, to "the Economy." Do they not realize that it takes a healthy economy to keep people healthy, and that if the economy dies, people die? People die, and countries die. There were many contributing factors to the downfall of the Soviet Union, but probably the largest was the failed Soviet economy. It must be done, but it must be done as wisely as we can. And that depends more on the people than on the government.

It's scary that so many people don't seem to realize that no one can wave a magic wand and then we can go back to "normal" behavior. That if the government decides to ease up a little on the reins, that doesn't mean you should grab the bit in your teeth and run wild. You take baby steps—suck the ice chips, sip the water, venture out a little more, keep your distance, wear a mask—and wait and see. Do what's important, and let the rest wait a bit.

I know it's time for Central Florida to open up a bit more. Maybe well past time. In hindsight, for hospitals to have cancelled all non-essential procedures probably did more harm than good. True, those ICU beds and respirators were there and available for the expected overwhelming onslaught of COVID-19 cases, but that hasn't come yet, and in the meantime many people have suffered unnecessarily. It's time we started replacing hips again.

But if we go crazy, if we flout the rules and recommendations, if we get careless, we once again risk bringing on COVID-19 infections at a rate greater than our medical system can handle. So I welcome the news that we've taken a step towards normal, but recognize it as a yellow flag, not a green one.

Therefore, we continue to be cautious, our children having taken pains to make sure we know we are old and therefore in a high-risk group. So there's not much to report from here. Just one short trip to the grocery store last week, where once again everyone was masked and the store was not crowded. My Google Maps Timeline is repetitious and downright boring. But my life is not!

Permalink | Read 1393 times | Comments (1)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories by C. S. Lewis, edited by Walter Hooper (Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1966)

Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories by C. S. Lewis, edited by Walter Hooper (Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1966)

The essays in this collection (On Stories, On Three Ways of Writing for Children, Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What's to Be Said, On Juvenile Tastes, It All Began with a Picture, On Criticism, On Science Fiction, A Reply to Professor Haldane, and Unreal Estates) are all included in C. S. Lewis: On Stories, which contains several additional essays as well, making the latter by far the more interesting book..

The remainder of this book consists of two little-known stories that were published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in the 1950's (The Shoddy Lands, Ministering Angels), one previously unpublished story (Forms of Things Unknown) and the beginnings of a novel inspired by the Trojan War (After Ten Years).

Forms of Things Unknown I enjoyed the most, for its clever, classical twist at the end, and because it alone has no female characters of any importance. The other three portray male attitudes toward women that lead me to despair of the human race. After Ten Years is nonetheless interesting, though only a fragment. Ministering Angels I wish I could forget. The Shoddy Lands has an appalling view of women, all the more so that I can tell from some of his non-fiction writings that it is somewhat reflective of Lewis's own experiences. Nonetheless, I find it the best of the four works, being an unforgettable portrayal of the self-centered blindness common to us all.

Now there's a title I'll bet no one else has used.

All the disruption caused by the COVID-19 virus turns out to have a positive side for us prosopagnosiacs. Suddenly all meetings are taking place via ZOOM, GoToMeeting, or some similar vehicle.

Think of the boon this is to those who suffer from face blindness! Suddenly everyone in the room is labelled! There's the person's picture, and right below it his name! The system is only as good as the names people choose to associate with their photos—I bless those who give their full names, rather than just "Jim"—but the chaos has been somewhat tamed. I'm particularly enjoying it in our church "happy hours" where I am finally, albeit very slowly, beginning to associate names, faces, and voices.

(As I was writing this, it occurred to me to wonder why I am not in favor of wearing name tags in church. It's actually a very helpful practice for people like me. I guess I still have scars from a church where the pastor used what he called "motivation by embarrassment" to encourage the wearing of nametags. If Martin Luther thought Satan could be driven away through the use of mocking and scorn, let me just say that it is also an effective method of driving shy and sensitive people far away from your church.)

It's interesting to me the different ways people react to this video social interaction. I find it helpful, but my husband finds it frustrating. I experience less chaos than in real life, he—accustomed to strictly-regulated business meetings—feels more. I know my daughter feels more comfortable with Zoom meetings than her husband does; I wonder if there is a difference between introverts and extroverts here as well?

I also find that meetings are more manageable if I listen more than I talk. I probably could learn something from that.

The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature by C. S. Lewis (Cambridge University Press, 1964)

The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature by C. S. Lewis (Cambridge University Press, 1964)

I knew I was out of my league here by page 23, when I read, "Plato's Republic, as everyone knows, ends with an account of the after-life...." No, I didn't know that. Neither 13 years of public education at well-respected schools, nor a college degree (University of Rochester, mathematics), nor growing up in a well-educated family (albeit with an emphasis on engineering and science), nor my own voluminous reading, led me to read anything, anything at all, by Plato. That I had even heard of him is thanks to Lewis's own Narnia books, wherein Professor Kirke exclaims, often enough to be memorable, "It's all in Plato, all in Plato: bless me, what do they teach them at those schools!"

Not much, apparently.

And generally not anything that Lewis would recognize as absolutely essential for one to be considered an educated man. What did they teach me at those schools? (I console myself, slightly, with the knowledge that Lewis couldn't handle mathematics. At all.)

But here's the funny thing: I still enjoyed reading the book, and have had my eyes opened to a little of the beauty, intelligence, and nobility of the Middle Ages, which modern culture thinks of simply as "dark." (And yet, and yet ... even George Lucas chose knights and swords and chivalry to tell his great futuristic story.)

It's a short book (not much over 200 small pages, and surprisingly easy to read despite Lewis's frequent use of terms in Latin, Greek, French, and Middle English, and his assumption that the reader is familiar with books that few of us have ever heard of, much less read. Don't let that throw you off; it's well worth reading.

One cannot hope to understand medieval literature, Lewis insists, without an appreciation for "the medieval synthesis itself, the whole organization of their theology, science, and history into a single, complex, harmonious mental Model of the Universe." (p. 11) Viewing Medieval works with a Modern mindset guarantees misunderstandings and wrong interpretations. The Discarded Image gives even woefully under-educated readers like me a few clues as to what we have been missing.

Not that you'll get those clues from my quotations, but here are some things that particularly struck me.

Despite what we enlightened moderns think of our backward ancestors,

The insignificance (by cosmic standards) of the Earth [was] as much a commonplace to the medieval, as to the modern, thinker." (p. 26)

In a prolonged war the troops on both sides may imitate one another's methods and catch one another's epidemics; they may even occasionally fraternise. So in this period [when Christianity was replacing Paganism]. The conflict between the old and the new religion was often bitter, and both sides were ready to use coercion when they dared. But at the same time the influence of the one upon the other was very great. During these centuries much that was of Pagan origin was built irremovably into the Model. It is characteristic of the age that more than one of the works I shall mention has sometimes raised a doubt whether its author was Pagan or Christian. (pp. 45-46)

No one who had read of Fortuna as [Boethius] treats her could forget her for long. His work, here Stoical and Christian alike, in full harmony with the Book of Job and with certain Dominical sayings, is one of the most vigorous defences ever written against the view, common to vulgar Pagans and vulgar Christians alike, which "comforts cruel men" by interpreting variations of human prosperity as divine rewards and punishments, or at least wishing that they were. It is an enemy hard to kill. (p. 82)

Note that Lewis died the year Joel Osteen was born....

Beyond the Stellatum there is a sphere called the First Movable or Primum Mobile. This, since it carries no luminous body, gives no evidence of itself to our senses; its existence was inferred to account for the motions of all the others. (p. 96, emphasis mine)

A technique scientists have been employing ever since!

The dimensions of the medieval universe are not, even now ... generally realized.... The reader of this book will already know that Earth was, by cosmic standards, a point—it had no appreciable magnitude. The stars, as the Somnium Scipionis had taught, were larger than it. Isidore in the sixth century knows that the Sun is larger, and the Moon smaller than the Earth, ... Maimonides in the twelfth maintains that every star is ninety times as big, Roger Bacon in the thirteenth simply that the least star is "bigger" than she. As to estimates of distance, we are fortunate in having the testimony of a thoroughly popular work, the South English Legendary: better evidence than any learned production could be for the Model as it existed in the imagination of ordinary people. We are there told that if a man could travel upwards at the rate of "forty mile and yet som del mo" a day, he would not have reached the Stellatum ... in 8000 years.

[These facts] become valuable only in so far as they enable us to enter more fully into the consciousness of our ancestors by realising how such a universe must have affected those who believed in it. The recipe for such realisation is not the study of books. You must go out on a starry night and walk about for half an hour trying to see the sky in terms of the old cosmology. Remember that you now have an absolute Up and Down. The Earth is really the centre, really the lowest place; movement to it from whatever direction is downward movement. As a modern, you located the stars at a great distance. For distance you must now substitute that very special, and far less abstract, sort of distance which we call height; height, which speaks immediately to our muscles and nerves. The Medieval Model is vertiginous. And the fact that the height of the stars in the medieval astronomy is very small compared with their distance in the modern, will turn out not to have the kind of importance you anticipated. For thought and imagination, ten million miles and a thousand million are much the same. ... The really important difference is that the medieval universe, while unimaginably large, was also unambiguously finite. And one unexpected result of this is to make the smallness of Earth more vividly felt. In our universe she is small, no doubt; but so are the galaxies, so is everything—and so what? ... To look out on the night sky with modern eyes is like looking out over a sea that fades away into mist, or looking about one in a trackless forest—trees forever and no horizon. To look up at the towering medieval universe is much more like looking at a great building. (pp. 97-99)

While the moral and emotional consequences of the cosmic dimensions were emphasised, the visual consequences were sometimes ignored. ... [Modern men] have grown up from childhood under the influence of pictures that aimed at the maximum of illusion and strictly observed the laws of perspective. We are mistaken if we suppose that mere commonsense, without any such training, will enable men to see an imaginary scene, or even to see the world they are living in, as we all see it today. Medieval art was deficient in perspective, and poetry followed suit. ... Nature, for Chaucer, is all foreground; we never get a landscape. And neither poets nor artists were much interested in the strict illusionism of later periods. The relative size of objects in the visible arts is determined more by the emphasis the artist wishes to lay upon them than by their sizes in the real world or by their distance. Whatever details we are meant to see will be shown whether they would really be visible or not. ... Of the medieval and even the Elizabethan imagination in general ... we may say that in dealing with even foreground objects, it is vivid as regards colour and action, but seldom works consistently to scale. We meet giants and dwarfs, but we never really discover their exact size. Gulliver was a great novelty. (pp. 100-102)

Aquinas treats the question [of astrological determinism] very clearly. On the physical side the influence of the spheres is unquestioned. Celestial bodies affect terrestrial bodies, including those of men. And by affecting our bodies they can, but need not, affect our reason and our will. They can, because our higher faculties certainly receive something ... from our lower. They need not, because any alteration of our imaginative power produced in this way generates, not a necessity, but only a propensity, to act thus or thus. The propensity can be resisted; hence the wise man will over-rule the stars. But more often it will not be resisted, for most men are not wise; hence, like actuarial predictions, astrological predictions about the behaviour of large masses of men will often be verified. (pp. 103-104)

The erroneous notion that the medievals were Flatearthers was common enough till recently. ... One [possible source] is that medieval maps, such as the great thirteenth-century mappemounde in Hereford cathedral, represent the Earth as a circle, which is what men would do if they believed it to be a disc. But what would men do if, knowing it was a globe and wishing to represent it in two dimensions, they had not yet mastered the late and difficult art of projection? ... A glance at the Hereford mappemounde suggests that thirteenth-century Englishmen were almost totally ignorant of geography. But they cannot have been anything like so ignorant as the cartographer appears to be. For one thing the British Isles themselves are one of the most ludicrously erroneous parts of his map. Dozens, perhaps hundreds, of those who looked at it when it was new, must at least have known that Scotland and England were not separate islands. ... And secondly, medieval man was by no means a static animal. Kings, armies, prelates, diplomats, merchants, and wandering scholars were continually on the move. Thanks to the popularity of pilgrimages even women, and women of the middle class, went far afield.... I doubt whether the maker of the mappemounde would have been at all disquieted to learn that many an illiterate sea-captain knew enough to refute his map in a dozen places. ... The cartographer wished to make a rich jewel embodying the noble art of cosmography, with the Earthly Paradise marked as an island at the extreme Eastern edge (the East is at the top in this as in other medieval maps) and Jerusalem appropriately in the center. Sailors themselves may have looked at it with admiration and delight. They were not going to steer by it. (pp. 142-144)

Marco Polo's great Travels (1295) is easily accessible and should be on everyone's shelves. (p. 145)

Sigh. A couple of thousand books on our shelves and not one of them is Marco Polo's.

I am inclined to think that most of those who read "historical" works about Troy, Alexander, Arthur, or Charlemagne, believed their matter to be in the main true. But I feel much more certain that they did not believe it to be false. I feel surest of all that the question of belief or disbelief was seldom uppermost in their minds. ... Everyone "knew"—as we all "know" how the ostrich hides her head in the sand—that the past contained Nine Worthies: three Pagans (Hector, Alexander, and Julius Caesar); three Jews (Joshua, David, and Judas Maccabaeus); and three Christians (Arthur, Charlemagne, and Godfrey of Bouillon). Everyone "knew" we were descended from the Trojans—as we all "know" how Alfred burned the cakes and Nelson put the telescope to his blind eye. As the spaces above us were filled with daemons, angels, influences, and intelligences, so the centuries behind us were filled with shining and ordered figures, with the deeds of Hector and Roland, with the spendours of Charlemagne, Arthur, Priam, and Solomon. It must be remembered throughout that the texts we should now call historical differed in outlook and narrative texture from those we should call fictions far less than a modern "history" differs from a modern novel. Medieval historians dealt hardly at all with the impersonal. Social or economic conditions and national characteristics come in only by accident or when they are required to explain something in the narrative. The chronicles, like the legends, are about individuals; their valour or villainy, their memorable sayings, their good or bad luck. (pp. 181-182)

I thought that in an age when books were few and the intellectual appetite sharp-set, any knowledge might be welcome in any context. But this does not explain why the authors so gladly present knowledge which most of their audience must have possessed. One gets the impression that medieval people, like Professor Tolkien's Hobbits, enjoyed books which told them what they already knew. (p. 200)

It has lately been shown that many Renaissance pictures which were once thought purely fanciful are loaded, and almost overloaded, with philosophy.

The book-author unit, basic for modern criticism, must often be abandoned when we are dealing with medieval literature. Some books ... must be regarded more as we regard those cathedrals where work of many different periods is mixed and produces a total effect, admirable indeed but never foreseen nor intended by any one of the successive builders. ... It would have been impossible for men to work in this way if they had had anything like our conception of literary property. But it would also have been impossible unless their idea of literature had differed from ours on a deeper level. Far from feigning originality, as a modern plagiarist would, they are apt to conceal it. ... They are anxious to convince others, perhaps to half-convince themselves, that they are not merely "making things up." For the aim is not self-expression or "creation"; it is to hand on the "historical" matter worthily; not worthily of your own genius or of the poetic art but of the matter itself. (pp. 210-211)

C. S. Lewis: A Companion and Guide by Walter Hooper (Harper San Francisco, 1996)

C. S. Lewis: A Companion and Guide by Walter Hooper (Harper San Francisco, 1996)

At over 940 pages in length, this is not a book for casual reading, although it is in large measure quite readable, and over time I read it all. It is more of a reference book, and as it covers nearly everything Lewis wrote, I've found it an invaluable "companion" on my "C. S. Lewis retrospective" journey. Hooper provides the background for each book, which I found by far the most interesting part, along with summaries of both the text and its reviews.

Despite its reference-book nature, I still found a few quotes to pass on.

When [Lewis] was seventeen, he learned that Arthur Greeves was ill, and wrote to him ... "Cheer up, whenever you are fed up with life, start writing: ink is the great cure of all human ills, as I have found out long ago." (p. 49)

That is the truth.

From Canto I of Lewis's poem, Dymer:

At Dymer’s birth no comets scared the nation,

The public crèche engulfed him with the rest,

And twenty separate Boards of Education

Closed round him. He passed through every test,

Was vaccinated, numbered, washed and dressed,

Proctored, inspected, whipt, examined weekly,

And for some nineteen years he bore it meekly. (p. 149)

Although written a hundred years ago, as a prophecy of modern American childhood it is chillingly accurate.

In the letter to Arthur Greeves of 18 August 1930 he said: "The side of me which longs, not to write, for no one can stop us doing that, but to be approved as a writer, is not the side of us that is really worth much. And depend upon it, unless God has abandoned us, he will find means to cauterize that side somehow or other." (p. 155)

From a letter to the publisher of Letters to Malcolm:

Would it be good to say "Some passages are controversial but this is almost an accident. The wayfaring Christian cannot quite ignore recent Anglican theology when it has been built as a barricade across the high road." (p. 380, emphasis mine)

Pauline Baynes, the illustrator of his Narnia books, speaking of a meeting with Lewis:

He answered, "Things one finds easy are invariably the best." This took a lot of thinking about, for though it is of course logical, up till then I had thought that nothing could be worthwhile that had not been a battle, a difficulty overcome, and that good things could only come after a lot of hard work and rubbing out. Of course he was right: if one knows about something so that you can draw it effortlessly it will be fluent and direct. (p. 407)

I could have avoided shopping this week, though we were out of several things in the produce line, so I'm glad I did. Since many businesses reopened yesterday, albeit with restrictions, I'm expecting an uptick in COVID-19 cases soon, so I'd rather shop now than later if I can. Not, I hasten to add, that I disagree with the idea of beginning to reopen businesses, though I think we may be being a bit hasty, and the last thing I want to do is to have to go back and do this all over again. Switzerland is starting from a strong position as far as virus cases go, plus they tend to be generally more compliant. The U.S. not so much.

Be that as it may, I had a great experience at the grocery store. Although there weren't many cars on the road at 7 a.m. (senior shopping is 7-8), I was not too happy with the number in the Publix parking lot. While I was still in the car, putting on my protective gear, I noticed a rather scruffy individual (but aren't we all scruffy these days?) coming out of the store, not wearing a mask. That made up my mind. I drove to another, smaller Publix not far away. Their parking lot was considerably less dense, and there weren't many shoppers in the store. Everyone I saw, customers and store workers, wore a mask, though I think I was the only one with gloves. True, one woman was wearing her mask around her neck—but the next time I saw her it was in the proper position.

I'm still inclined to believe the doctors who say that nothing less than a properly-fitted N95 mask will protect the wearer from the virus. So, why do I wear one? First of all, my lovely homemade mask (no, I didn't make it) has non-woven fabric between the layers of cotton, which does a much better job of catching virus particles. It still leaks around the edges, but it will help contain an errant cough or sneeze on my part, and I always thought non-hospital masks were more about protecting other people, rather than the wearer, anyway.

But most of all, I wear a mask because of what it says to other people. We have reached the point where masks have become such an issue that not wearing a mask sends an "I don't care about anyone else" message. Possibly that is 100% wrong, but it's what we have to deal with right now, and I consider it a small price to pay to send an encouraging message to a neighbor—and possibly protect him a bit, too.

(On the other hand, the problem with masks is that they hide smiles, and a smile is a pretty encouraging message all by itself.)

So, everyone was wearing masks, everyone was friendly, everyone kept a decent distance (usually well more than six feet), PLUS they finally had my favorite hamburger and hot dog buns in stock, and they were BOGO! What's not to like?

For the record, and the curious, the shelves were well stocked. There were a couple of empty spots, rather odd I thought: I mean, frozen French fries and green beans? I could have bought just about anything else, though not always my favorite brand in the paper goods department. Meat, which I've been told is the next "toilet paper," was plentiful.

Permalink | Read 1244 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

My Google Maps Timeline is boring: I haven't been anywhere since my grocery store outing on April 21st. Not that I'm suffering much, except for not being able to forget that we celebrated Porter's birthday quietly, when the pre-COVID-19 plans were for his children, their spouses, and his grandchildren all to be here celebrating with him. Trust me, that would not have been quiet. Other than that, there's always so much going on at home that boredom is out of the question.

But sometimes one must leave the house, and this week was Porter's turn.

His first trip, to Costco during their "senior hours," was very successful. They are now very well organized with their shopping and check-out procedures, so that shopping was not stressful and felt safe. The shelves were stocked, including toilet paper and kleenex.

His second and third trips were successful, but not so comfortable. Our favorite local pool store was not practicing any form of distancing, the employees didn't wear masks, and they still required the credit card slip to be signed, happily providing the same pen to all customers.

I'm not at all convinced that the masks do as much good as many people think. But they contain the larger droplets, and—effective or not—are a statement that the store and the people are at least thinking about safety.

This coming week may be my outing. It's impossible to stock up on fresh fruits and vegetables, so I'll probably make a trip to the grocery store when the senior shopping days come around. Unless we get a big spike in cases due to things beginning to open up around here.

Still no church, though. It's frustrating to see how different my own values are from what is revealed by the phased-in "return to normal" schedule. And it's not just crazy American priorities: in Switzerland, hair salons were in the first phase! True, I could use a haircut, but I'd hardly give that high priority, and no one is going to give me a haircut from six feet away. They're also sending kids back to school, which really makes no sense at all, and I'm glad our district is staying closed for the rest of the school year. It's still illegal for people to gather in groups greater than five in Switzerland, even with social distancing—yet they're sending children to classrooms of several times that, and you know they cannot—and will not, even if they could—stay six feet apart. Here, restaurants are among the first businesses to open; again, something I consider dangerous and so far from a necessity I'd keep them closed a lot longer.

If we really can afford to open things back up, I'm grateful. I just don't want to move so fast that we have to clamp down again for a second (or third, or fourth) wave. You know, like going back to normal eating too soon after a bout of stomach flu. Besides, I don't really want to return to "normal." If we don't find ourselves in a "new normal" that is better than the old one—as individuals, families, communities, businesses, and governments—we will have wasted the suffering of the last few months. Let's learn something! Let's learn a lot.

At least my closets are getting cleaned—and that's no small thing to be thankful for.

Permalink | Read 1323 times | Comments (3)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer by C. S. Lewis (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1963)

Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer by C. S. Lewis (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1963)

Unlike Lewis's Letters to Children, this "correspondence" between Lewis and the fictional Malcolm is a literary device, a platform he used for writing speculatively, rather than authoritatively, on prayer. He had tried years earlier to write an ordinary book on prayer, but found it coming out too much like "teaching" for him to feel comfortable writing, as a layman. In a sense this is more like The Screwtape Letters, but without the humor and the skewed perspective.

Authoritative or not, there's a lot of wisdom in this, the last book Lewis wrote.

The crisis of the present moment, like the nearest telegraph-post, will always loom largest. Isn't there a danger that our great, permanent, objective necessities—often more important—may get crowded out? By the way, that's another thing to be avoided in a revised Prayer Book. "Contemporary problems" may claim an undue share. And the more "up to date" the book is, the sooner it will be dated. (p. 12, emphasis mine)

I find that problem with Holy Eucharist Rite II of the Episcopal Church. Rite I is older, but to me feels more relevant and less dated than some of the passages in the newer version, introduced in the late 1970's. There are a few things I like better about Rite II, but really, some of the prayers there actually make me wince. Not in a good, convicted-of-sin way; more like when I see a 1970's hairstyle in an old photograph. Bringing out still another version of the Prayer Book would not solve the problem, but only make it worse—it would become dated even sooner.

The increasing list of people to be prayed for is ... one of the burdens of old age. I have a scruple about crossing anyone off the list. When I say a scruple, I mean precisely a scruple. I don't really think that if one prays for a man at all it is a duty to pray for him all my life. But when it comes to dropping him now, this particular day, it somehow goes against the grain. And as the list lengthens, it is hard to make it more than a mere string of names. (p. 66)

That one hit home. Not only with my own prayers, but especially with our church's prayer ministry. Once upon a time, the prayer list was small enough that we could receive details and regular updates and felt connected with those we were praying for, even those we didn't know. Now it has grown so large that it is indeed little more than a string of names of strangers. God knows who and what we are praying for—but something has been lost.

As Lewis said, it's very hard to take someone off a prayer list, especially those with long-term needs. But when my own list approaches a certain critical size, I find my reluctance to pray (instead of just thinking about it) increases exponentially. As with so many things in life, the trick is finding the right balance, I guess.

In Pantheism God is all. But the whole point of creation surely is that He was not content to be all. He intends to be "all in all." (p. 70)

I talked to a continental pastor who had seen Hitler, and had, by all human standards, good cause to hate him. "What did he look like?" I asked. "Like all men," he replied. "That is, like Christ." (p. 74)

God is present in each thing but not necessarily in the same mode: not in a man as in the consecrated bread and wine, nor in a bad man as in a good one, nor in a beast as in a man, nor in a tree as in a beast, nor in inanimate matter as in a tree. I take it there is a paradox here. The higher the creature, the more, and also the less, God is in it; the more present by grace, and the less present (by a sort of abdication) as mere power. By grace he gives the higher creatures power to will His will ("and wield their little tridents"): the lower ones simply execute it automatically. (pp. 74-75)

It is well to have specifically holy places, and things, and days, for, without these focal points or reminders, the belief that all is holy ... will soon dwindle into a mere sentiment. But if these holy places, things, and days cease to remind us, if they obliterate our awareness that all ground is holy and every bush (could we but perceive it) a Burning Bush, then the hallows begin to do harm. (p. 75)

Joy is the serious business of Heaven. (p. 93)

Of course I pray for the dead. The action is so spontaneous, so all but inevitable, that only the most compulsive theological case against it would deter me. And I hardly know how the rest of my prayers would survive if those for the dead were forbidden. At our age the majority of those we love best are dead. What sort of intercourse with God could I have if what I love best were unmentionable to Him?

On the traditional Protestant view, all the dead are damned or saved. If they are damned, prayer for them is useless. If they are saved, it is equally useless. God has already done all for them. What more should we ask?

But don't we believe that God has already done and is already doing all that He can for the living? What more should we ask? Yet we are told to ask.

"Yes," it will be answered, "but the living are still on the road. Further trials, developments, possibilities of error, await them. But the saved have been made perfect. They have finished the course. To pray for them presupposes that progress and difficulty are still possible. In fact, you are bringing in something like Purgatory."

Well, I suppose I am. ... I believe in Purgatory. Mind you, the Reformers had good reasons for throwing doubt on "the Romish doctrine concerning Purgatory" as that Romish doctrine had then become. I don't mean merely the commercial scandal. If you turn from Dante's Purgatorio to the sixteenth century you will be appalled by the degradation. In Thomas More's Supplication of Souls Purgatory is simply temporary Hell. ... Its pains do not bring us nearer to God, but make us forget Him. It is a place not of purification but purely of retributive punishment.

The right view returns magnificently in Newman's Dream. There, if I remember it rightly, the saved soul, at the very foot of the throne, begs to be taken away and cleansed. ... My favorite image on this matter comes from the dentist's chair. I hope that when the tooth of life is drawn and I am "coming round," a voice will say, "Rinse your mouth out with this." This will be Purgatory. The rinsing may take longer than I can now imagine. The taste of this may be more fiery and astringent than my present sensibility could endure. But [they] shall not persuade me that it will be disgusting and unhallowed. (pp. 107-109)

Let's now at any rate come clean. Prayer is irksome. An excuse to omit it is never unwelcome. When it is over, this casts a feeling of relief and holiday over the rest of the day. We are reluctant to begin. We are delighted to finish. While we are at prayer, but not while we are reading a novel or solving a cross-word puzzle, any trifle is enough to distract us. ... And we know that we are not alone in this. The fact that prayers are constantly set as penances tells its own tale. (p. 113)

The disquieting thing is not simply that we skimp and begrudge the duty of prayer. The really disquieting thing is it should have to be numbered among duties at all. For we believe that we were created "to glorify God and enjoy Him forever." And if the few, the very few, minutes we now spend on intercourse with God are a burden to us rather than a delight, what then? If I were a Calvinist this symptom would fill me with despair. ... If we were perfected, prayer would not be a duty, it would be delight. Some day, please God, it will be. (pp. 113-114)