Is it better to be hated, or ignored? To be thought evil, or irrelevant?

It's a common saying that hate is not the opposite of love—indifference is. Because the former indicates one cares, it can be more easily turned around.

I'm not so sure what I think about that now.

Secularism in America tends to be aggressive, even nasty. It is not neutral, but negative; not impartial, but specifically anti-Christian. (The latter is not too surprising, as we tend to be hardest on that which we think we are rebelling against.) Secularism, as practiced by most Americans, is also uneducated. We reject any number of faiths without knowing, much less understanding, their most basic tenets.

I know very little about Europe, and fully expect to be corrected by those who live there. But my experiences and impressions lead me to believe that European secularism is of a different sort. They are proud of their Christian heritage. They love their big, beautiful churches, and can give you a decent explanation of the facts of the faith and history that inspired them. They have respect for the value of education in the facts about a religion, even if they no longer believe them to be valid.

America's fierce secularism about holiday names must perplex the Europeans who have the sense to take whatever holidays they can, and have no problem calling them by their traditional names, whether Christmas, Easter, Pentecost, or even Mariähimmelfahrt. (I remember the last because it makes it appear that they close the stores in Lucerne for my grandson's birthday.) No "Winter Holiday" nonsense there.

But for most Europeans this surface Christianity has no impact on their lives. They are proud of their heritage and churches in the same sense that they are proud of their classical heritage and the Parthenon. They think no more of the Holy Spirit on Pentecost than we think of Thor on Thursday. The best use of those big, beautiful churches seems to be for generating tourist income—or, as one resident of Amsterdam explained to us, as party venues. Europeans know the basic facts, but think them irrelevant.

So ... is it better to be hated or to be ignored? I've seen enough hate on Facebook alone to make me doubt that the one is more easily turned than the other. Europe may be letting its active Christianity languish, but the foundation is there, ready to be unearthed by some curious archaeologist. America is iconoclastic and shares with ISIS, the French Revolution, and Byzantine Emperor Leo III the belief that it's better to destroy priceless art and history than to risk the curious being led astray.

Permalink | Read 1445 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

One hundred years ago today, on November 11, 1918, on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, the armistice was signed that ended battle on the Western Front of World War I, the war that devastated a generation of Europeans, and set the stage for World War II two decades later. The cost was personal on this side of the Atlantic as well.

Veterans' Day is a time for honoring all veterans, but this year it seems appropriate to feature WWI. Those closest to us include:

Hezekiah Scovil Porter, son of Wallace and Florence (Gesner) Wells Porter. Porter's granduncle on this mother's side. Army, 26th Division, 101st Machine Gun Battalion. Killed in action near Chatêau-Thierry, France, July 22, 1918. His story is elaborated here: The Complete World War I Diary of Hezekiah Scovil Porter.

Harry Gilbert Faulk, son of Olaf Frederick and Hilma Justina (Reuterberg) Faulk. Porter's granduncle on his father's side. Army, 26th Division, 101st Machine Gun Battalion. Wounded in action near Chatêau-Thierry, France, July 25, 1918. Died of his wounds later that day. Here is a (mostly accurate) article about him.

Howard Harland Langdon, son of Willis Johnson and Mary Lucy (Wood) Langdon. My grandfather on my father's side. Army, 219th Aero Squadron, served in England. He didn't fly the planes, but kept them air-worthy.

George Cunningham Smith, Sr., son of Nathan and Issyphemia (Cunningham) Smith. My grandfather on my mother's side. Army, 5th Engineers, Company B, served in France. His father fought in the Civil War (16th Pennsylvania Cavalry, Company B).

Thank you to all who have stood "between their lov’d home and the war’s desolation."

Permalink | Read 2099 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

What's this "set your clocks back" warning I heard all over the media yesterday?

What's a clock?

I wonder how archaic this advice really is. I also wonder why people raise so many objections to "changing the clocks" twice a year.

Yes, I know: I've campaigned against the time changing. But that's because I want to stay on Standard Time (aka real time, sun time, normal time) all year 'round and not use Daylight Saving Time—one of Ben Franklin's less reasonable ideas—at all. The change itself is trivial for one accustomed to dealing with time zone changes.

But when you woke up this morning, how did you know what time it was?

I'm betting most people checked their phones—phones which are smart enough to make the time change without our help.

If I had set my computer clock back an hour, it would now be wrong.

Yes, we changed our clocks yesterday—and I remarked that we have far too many of them that need changing. I can't help believing that they are an anachronism. Houses in the future may still have clocks, but I'm betting more and more of them will be smart enough to change themselves. And in any case, people will still rely more on their cell phones to wake them up in the morning and get them where they need to go on time.

The "change your clocks" sermons are being preached to an ever-dwindling congregation.

Permalink | Read 1749 times | Comments (3)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Pardon me while I briefly indulge my Inner Cynic.

Strangers cross your borders unbidden. They are miserable, hungry, and lack the skills necessary to live in your land. You are compassionate. You welcome them, feed them, and teach them survivial skills. You enjoy the boost they bring to your economy.

Ask the Native Americans how that worked out for them.

Happy Thanksgiving.

Permalink | Read 1410 times | Comments (8)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Quiz: How well can you tell factual from opinion statements?

This isn't one of those silly Facebook quizzes, like the one that purports to tell you what voice part you should sing based on personality questions—the one that told me I should be singing low bass. It's from the Pew Research Center, and consists simply of 10 political statements for you to classify as factual or opinion. I thought they were all obvious and scored 5/5 on the factual statements and 5/5 on the opinion statements. Alas, the "nationally representative group of 5,035 randomly selected U.S. adults surveyed online between February 22 and March 4, 2018" did not do so well: only 26% had a perfect score on the factual part, and 35% on the opinion section.

If you take the quiz (which does not require an e-mail address, signing in, or anything else intrusive), you'll get to see not only your results but a breakdown of the people who answered each particular question correctly, based on political party affiliation and how much they trust national news organizations. The first is particularly interesting, if somewhat depressing. Unfortunately for partisans, there's no evidence that Democrats are smarter than Republicans, or vice versa. Sometimes one party fared better, sometimes the other. What is clear is that both parties have a strong tendency to label statements consonant with their own beliefs as fact, and statements that they disagree with as opinion. This despite the clear instructions:

Regardless of how knowledgeable you are about each topic, would you consider each statement to be a factual statement (whether you think it is accurate or not) or an opinion statement (whether you agree with it or not)?

What I find find disturbing is the apparently lack of understanding that a statement of fact can be wrong. "I have red hair" is a statement of fact—one that happens to be false. So is "I like to eat liver" (also false). The latter statement is factual, not opinion, even though it states my opinion of the taste of liver. "Liver is disgusting" is an opinion statement, and my agreeing with it does not make it factual.

It seems we have carried "I'm right, you're wrong" to a whole new level.

I don't need to agree with Elizabeth Warren to recognize that she doesn't deserve all the grief she's getting for celebrating her Native American ancestors. Not from President Trump, not from the Republicans, not from the Democrats, and not even from Native Americans themselves.

Warren's memory of family stories is that somewhere among her forebears were some Native Americans. As a genealogist, I know that this is a fairly common family mythology, and that most of the stories turn out to have no basis in fact. Porter's family had just such a story about "our Indian ancestor," but I've found nothing to back that up in any of my extensive research. (That's okay; he has plenty of other interesting ancestors.)

Donald Trump mocked Warren for this claim, and challenged her to back it up with DNA testing. Recently she released the results: it's likely that somewhere, several generations back, she did indeed have Native American ancestry (from North, South, or Central America). More specific than that can't be said.

But now everyone is jumping on her, from the President to speakers for the Native American communty (not that they all agree), from the Left to the Right. The ancestry, if it exists at all, is too far back to count, they say. Tribal identity is not determined by genetics.

The report states that Elizabeth Warren's most recent Native American ancestor is six to ten generations back. According to many, that makes her heritage insignificant.

As far as I have been able to determine in my research, my own most recent immigrant ancestor is five generations back; most are ten or even more. All of my parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, and great-great-grandparents were native-born Americans. So were all but two or three of my 32 great-great-great-grandparents. Beyond that, the data is not complete, but the percentage of native-born great-great-great-great-grandparents is at minimum more than 50%, and most of them were born before the United States even existed. If ancestors that far back don't count, does that make me Native American?

Of course not. And if Elizabeth Warren's Native American ancestry starts back six to ten or even more generations, it's still her own ancestry. Even if her DNA results had come back negative, it's still quite possible that her ancestry includes Native Americans, because the random recombination that happens from generation to generation means that you have ancestors who didn't give you any of their genes. Genetics isn't genealogy, and genealogy isn't genetics. Your great-great-grandfather is still yours, even if his genes aren't.

So what does this mean for Elizabeth Warren? Can she expect preferential treatment because of her Native ancestry? No, nor as far as I know, has she asked for it. Can she claim membership in a particular, modern tribe? Again, no. Even if the DNA test were tribe-specific, which it is not, qualifications for tribal membership are not based on DNA tests. Again, I believe she has not asked for any such thing.

But to celebrate one's ancestors and ancestral heritage, no matter how small? That's everyone's right. The current government of the Netherlands has no reason to grant me citizenship, but they can't deny my Dutch 9th-great-grandfather, and visiting Holland this summer was a bit more special because I know he existed. Similarly, England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Germany, and France hold a special place in my heart because of my ancestral roots. Should I not feel a special thrill standing on English soil because it has been three and half centuries since my English ancesors crossed the Atlantic?

I will celebrate my heritage, no matter how far back. I will also feel connected to Australia, Brazil, Japan, New Zealand, The Gambia, and any other country I have been privileged to visit, even if we have not a single gene in common. I will enjoy their cuisine and their culture, take an interest in their history and politics, and care about their people. If this be treason, I'll make the most of it.

Go, Ms. Warren! Celebrate your heritage and let the chips fall where they may.

Permalink | Read 1411 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Big things matter. Ask an employee what he wants from his employer, and you'll likely—and rightly—hear about salary, benefits, and a workplace that is physically and emotionally safe. He probably won't think the little things are worth mentioning, but businesses need to be more aware that small investments in employee relations often have a disproportionately large impact.

Back in the days when long-distance telephone charges were a significant item in a family's budget—I know that for many people that sets the time back in the Civil War, but it wasn't—one of the benefits we enjoyed from Porter's job with AT&T was a $35/month credit for long-distance services. In strict financial terms, it was a pittance, and hardly could have made much of a difference to the bottom line of such a big company, but what it bought in feelings of goodwill toward AT&T on the part of its employees' families made it one of their better investments.

When corporations start feeling a financial pinch, however, those whose job it is to find ways to save money do not always see the whole picture.

I'm currently reading Highest Duty (by Captain Chesley "Sullly" Sullenberger and Jeffrey Zaslow; thanks, DSTB!), the book on which the movie Sully is based. This is not a review, though I will say that so far I'm enjoying the book. But one incident haunts me, unexpectedly.

Captain Sullenberger was a pilot for USAirways, but I've no doubt that with all the financial problems of the industry, other airlines were and are no better. Indeed, the financial story is true for industries across the board, and mirrors the experiences we had with AT&T and IBM. Pilots' salaries were slashed, and their pensions gutted—but that's not what haunts me. It's the peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

Airlines once provided their pilots and flight attendants with free meals on long-haul flights. A small enough service, surely! But that, too, was cut, and Sullenberger began brown-bagging his lunches. Ask a pilot his priorities, and safety, salary, and benefits will top the list. But we should never underestimate the corrosive power of eating a peanut butter and jelly sandwich whilst inhaling the scents of beef tenderloin that waft in from First Class. Providing a few extra meals on long flights would seem a prudent investment in employer-employee relations, with the potential return in good will and good feelings disproportionately high compared with the cost.

I can't change corporate culture, but I wonder: What small investments of our time, money, and attitudes can we, as individuals, make that carry the potential for high return in someone else's life?

Permalink | Read 1462 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

For those of you who think I'm just a classical music snob....

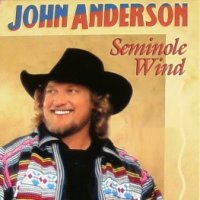

I don't remember where I came across this beautiful country song—odds are it was somewhere on Facebook—and I hesitate to share it, since embedded YouTube videos are no longer working for me. But you can click on the image to hear John David Anderson's haunting Seminole Wind. (That's fixed now; see below. I've also made minor changes to the lyrics transcription.)

It's a song to tear at the heart of a Floridian, even a semi-native such as I. In addition to all the other emotions it evokes, it takes me back to the days when the YMCA wasn't ashamed to call its Parent-Child programs "Indian Guides" and "Indian Princesses." Now it's "Adventure Guides" and the Native American connection is lost. Back then, the Florida Indians—who at that time preferred "Indian" to "Native American"—welcomed the Y tribes to their own pow-wows. I can still hear the drums, the voices, and the prayers, and taste the fry bread....

Not to mention that a love of wilderness areas was bred into my bones, whether New York's Adirondacks or Florida's wetlands, scrubs, and hammocks.

And I'm a sucker for Dorian mode.

Ever since the days of old,

Men would search for wealth untold,

They'd dig for silver and for gold,

And leave the empty holes.

And way down south in the Everglades,

Where the black water rolls and the saw grass waves,

The eagles fly and the otters play,

In the land of the Seminole.

So blow, blow Seminole wind,

Blow like you're never gonna blow again.

I'm callin' to you like a long-lost friend,

But I know who you are.

And blow, blow from the Okeechobee

All the way up to Micanopy.

Blow across the home of the Seminoles,

The alligators and the gar.

Progress came and took its toll,

And in the name of flood control,

They made their plans and they drained the land,

Now the Glades are goin' dry.

And the last time I walked in the swamp,

I sat upon a cyprus stump.

I listened close and I heard the ghost

Of Oseola cry.

So blow, blow Seminole wind,

Blow like you're never gonna blow again.

I'm callin' to you like a long-lost friend,

But I know who you are.

And blow, blow from the Okeechobee

All the way up to Micanopy.

Blow across the home of the Seminoles,

The alligators and the gar.

Songwriter: John David Anderson

Seminole Wind lyrics © Universal Music Publishing Group

Here's the video now; thanks to Lime Daley for fixing my problem.

I came upon the following in a book I'm reading:

During the 1800s, a person got from one place to another one of four ways: by foot, animal (usually a horse), ship, or boat. By the second half of the century there was a fifth option—train.

The nautical people in my family would not have been surprised, as I was, to see "ship" and "boat" listed separately. Wikipedia starts its entry for Ship with "Not to be confused with boat." Which I do, a lot. And the nautical people in my life feel insulted, especially if they have boats of their own—or ships, or something else that usually floats and costs a lot of money.

Here's a summary of some of the differences between a boat and a ship. It's not so much that I don't know, as that I don't care—which is probably still more offensive to those of the sailing persuasion.

On the other hand, I suppose that in the 19th century, along America's eastern shoreline, the difference between "boat" and "ship" was as significant as that between "pistol" and "rifle," or maybe "rifle" and "cannon." And I have at least one friend who would no doubt be similarly insulted if I called his 1899 Swedish Mauser a "gun."

Still, I was surprised enough to go back and reread the sentence, convinced I'd read it wrong.

Permalink | Read 1566 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

When you are young you write either romantic or depressive poetry or both. When you are older, you write stories of whatever genre. But you know you are really getting old when you start writing essays!

— Anaya Roma, The Mindverse Chronicles, "Going to Hell."

I am officially old, and have been much of my life.

Not because of the grey in my hair;

Not because I'm on Medicare.

Not for the wrinkles on my face,

Or because my grandson can sing bass,

And today my granddaughter is turning ten.

No, I am marked by the strokes of my pen:

Sad poems and novels were never my art;

The essay's the form that speaks from my heart.

My muse was set in the days of my youth:

To seek, and ponder, and write the truth!

Permalink | Read 1565 times | Comments (1)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I don't care if your question is about climate change or about your niece's latest romance, I can answer it with two words: It's complicated.

Simplistic answers to complex problems sadden and infuriate me. That's how we end up leaping from one problem to another, from one error to a different error.

My father always greatly admired people who, when seeing a job that needed to be done, just did it, without debate and without complaining that it was really someone else's responsibility. I mostly agree with him, and when our kids were growing up, we had something called "Grandpa's Award" that I gave out when I observed such behavior.

While that philosophy works heart-warmingly well on smaller points, such as washing dishes, changing a diaper, or running an errand, most larger issues are not well managed without research, thought, and debate—yet we still jump on simplistic answers, embarking on pathways that accomplish little at high cost, or even result in great harm. Out of compassion, we are quick to donate money to what appear to be good causes, not seeing in the end the food rotting in port instead of being distributed to starving people, the books mouldering in a forgotten storage closet, the money enriching the coffers of corrupt politicians and businessmen. Dreaming of an end to poverty, we pass laws providing for the needs of indigent single mothers and children, only to find that we've created a culture in which it is to a family's financial advantage for the father to be absent, and young girls seeking independence have an incentive to get pregnant. German chancellor Angela Merkel, responding to an urgent, growing, and heart-wrenching refugee crisis, quickly opens the doors of her country without consideration for those who warned that there should first be put into place a workable plan. Now both Germany and the refugees are suffering from the inevitable consequences of trying to absorb a large influx of people with great needs and a markedly different culture, and of a significant portion of the population who feels unheard and unrepresented, and can rightly say, "I told you so."

All this came to mind because of the recent outcry against plastic straws. I am certainly appalled at the waste produced by the restaurant industry, but what does banning plastic straws really do? It seems we've once more jumped on a feel-good bandwagon without actually researching the problem. In our house, replacing plastic straws with something biodegradable would create a good deal more waste, since we wash and reuse plastic straws hundreds of times—we are still less than halfway through the package we bought four years ago. What waste is created, what environmental damage done when a company retools its system to create a substitute for its plastic straws? Is the good accomplished commensurate with the cost incurred—especially since the biggest man-made contaminant of the world’s oceans is not plastic straws, or even plastic bags, but cigarette butts?

You will understand, then, my appreciation for a recent post by my friend Eric Schultz on his Occasional CEO blog: Food Foolish #8: What About the Birds? As co-author of Food Foolish: The Hidden Connection Between Food Waste, Hunger and Climate Change, he might be expected to endorse uncritically any attempt to reduce the large quantity of food that ends up in our landfills. Inspired by a listener's question at one of his lectures, however, he decided to investigate this problem: How dependent are birds on human food waste, and what happens if we reduce it—as so many individuals, corporations, and governments are now committed to doing?

That turns out to be a complicated question with not enough data for a clear answer. It's worth reading his analysis.

If even something as obviously good as reducing food waste has unintended consequences to consider, surely our thornier environmental, social, and political problems could benefit from more research and thought and fewer highly-charged emotions, from a lot more light and a lot less heat.

Permalink | Read 1545 times | Comments (1)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

As usual, jet lag is kicking me on the return trip. (The outbound trip is much easier, for several reasons.) I had thought I was over it the first day—but it turns out I was only so exhausted that sleep came at any time, any place. :) But it's getting better. Gradually, my wake-up-and-can't-get-back-to-sleep time has stretched from 2 a.m. to 3 a.m. to this morning at 4:30 a.m.—almost normal. I knew there was no hope of getting back to sleep today, because I woke up thinking about how far away our children and grandchildren are, and how much that not only hurts now but potentially makes life difficult years from now if we don't get hit by a truck but have to face becoming too old and infirm to live independently. a sad situation many of our friends are currently going through with their parents.

Lying in bed awake was not producing any solution to that problem, so I got up and went to work. And one of the first things I ran across, on a totally and completely unrelated search, was this song: "The Missing Piece," by Cherish the Ladies.

Yes, I cried.

There's a sadness woven throughout Irish music, despite the gaiety of many of its songs. Naturally, this song of family far away and of the expat's dilemma—homes in two countries and yet a stranger to both—moved me especially this morning. Like most music of this sort, it also dredged up other sorrows, present and ancient, from family visits recently postponed to the loss of loved ones almost half a century ago.

We need such moments of grief and remembrance, and that's one of the strengths that make Irish music what it is.

Then it's time to move on and get to work. (After writing about it, of course. That's how I cope.)

I first noticed it when Porter was working with coworkers from India, part of the great outsourcing/offshoring boom in the early part of this century. He had discovered that he could never make more than one point in an e-mail. If he asked two questions or brought up two subjects—let alone a list of several—his correspondent would respond to one of them, usually either the first or the last, and completely ignore the rest. At the time, I blamed it on the language barrier.

Now I don't know what say, because it happens all the time, with people for whom English is as native as language can get. Over and over again people seem to be missing everything after the first paragraph of an e-mail.

Could it be a Twitter Effect, and people just can't take in more than 140 characters at a time? Have our attention spans degenerated so drastically? Are we perhaps just so busy, hurried, and harried, trying to accomplish too much in too little time, that we can't take time to read carefully? I think of doctors, nurses, teachers, and others who complain that they are so rushed they can no longer do their jobs properly. It may be those in the helping professions who feel it first and foremost, but it's no doubt true of us all.

Should we, perhaps, call ourselves a post-literate society? Once upon a time, not that long ago, literacy was not taken for granted. It wasn't until 1940 that the U.S. Federal Census stopped asking people if they could read and write. But thereafter, every schoolchild was expected to learn to read and to write, and libraries flourished.

Now, I'm not so sure. Schools still teach reading and writing, but are we now creating graduates who can read, but don't? So many people never touch a book after leaving school! We've gone from reading solid, well-written, even scholarly books, to "beach reads," to newspapers and magazines, to USA Today, to blogs, to Facebook and Twitter, click-click-click. From long, newsy letters to e-mails to Instagram and Snapchat.

Certainly, there have been gains with each step. But we've also lost something important. I know people who can read very well, but have no patience with an e-mail that is longer than a few sentences. At least I don't need to worry about offending anyone with this blog post—the guilty won't get this far. :)

Ah well, one must move with the times. Pardon me while I go snip an e-mail into bite-sized fragments.

Permalink | Read 1438 times | Comments (5)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I try hard not to judge a president, for good or for ill, until years after his term has ended. History does much to clear the clouded lens of the present, and more than once a person I've judged as good has turned out to be a lousy president, and vice versa. But I think I can say that if Americans, and the American media, are waking up to the fact that danger from Russia did not go away with the end of the Cold War, that's a good that might last. We need do the same with China and a few other countries, too.

Does that mean we should hate these countries and view them as our enemies? Of course not. On the personal level, meeting, loving, appreciating, and valuing other people and cultures is the road to peace—not to mention to learning, growth and a lot of fun.

But at the political level, it's important never to forget that other governments, even at their best, have the interests of their own people in mind, not ours. And that's a good thing; that's their job. It's our government's job to look to the interests of our country and our people, and that is the messy business of diplomacy—including but not limited to economic policy, military strength, espionage, cyber security, foreign aid, political rhetoric, looking for the win-win even with our enemies, compromise, and all the complex art of statecraft.

Does that mean we should give our government a free hand to use whatever tactics will get the job done? Absolutely not. Free and democratic countries must face the world with one arm tied behind their backs, not resorting to immoral behavior even if it's used against them, just as the police are not allowed to use criminal behavior to catch criminals. It does mean, however, that we must be the more vigilant and active to use all legitimate means to further our goals.

It is what Scottish author and philosopher George MacDonald called, "sending the serpent to look after the dove," a reference to Jesus' admonition to be "wise as serpents and harmless as doves" (Matthew 10:16). Innocence with knowledge and wisdom is strong.

As you can imagine, two years after the event there has been a lot of action here recently, memorializing the Pulse nightclub shooting and the tragic loss of 49 lives. But the death toll at Pulse that night was not 49. It was 50.

I understand the visceral response that wants to leave the the attacker, who was subsequently shot by police, out of the picture. It's a completely natural reaction and I don't hold anything against those—especially of the victims' friends and family—who limit their compassion to the 49.

What I don't understand is why churches are following the same path. The natural way is not the Christian way. It is very, very clear that we are to love our enemies, which at the very least means mourning the violent, if necessary, death of this angry and unstable young man. He, as much as any of the other victims of this tragedy, was someone's son, someone's brother, someone's father, a human being, created in the image of God—no matter how distorted that image had become.

Churches, when you ring out the memory of the lost from the Pulse tragedy, remember that you are to be in the world but not of it. Don't take the natural course, but the supernatural: Let your bells toll the full 50 strokes.

Permalink | Read 1464 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]