This is not my own, but the person I learned it from can't remember where she first found it. And it's not a direct quotation, because I've modified it to sound better in my own ears. But the sentiment is exactly the same.

"A writer is a writer not because he has amazing talent. A writer is a writer because, even when nothing he does shows any sign of promise, he keeps on writing anyway."

This morning I read part of an article called "Is Florida the New Wall Street?" That link should take you to the same part, though to go any further you need to have a Business Insider subscription, which I don't. The beginning paragraphs were enough to get me thinking about the idea, however.

When the pandemic hit New York City, Florida was overwhelmed with people from New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut who had decided to flee here. When our governor attempted to impose a quarantine period, he was overwhelmingly mocked, derided, and shut down by New York and other states, with cries of "overreaction" and "interference with interstate commerce." Of course, it was not long before New York and many other states turned around and decided to implement their own quarantines. It reminds me of the European assault on President Trump for closing our borders—and their subsequent decisions to do the same thing themselves. Mind you, I was not happy with the president's decision to close off traffic from Europe, since it happened just in time to cancel a long-awaited visit from our Swiss family. But the hypocrisy of the reaction (from both Europe and New York), without any apology when they decided to implement the same policies, is galling.

But this post is not actually about the pandemic directly. It's about another flood of New Yorkers who might be coming Florida's way.

The pandemic and the rise of remote work are accelerating movement from the Northeast to the Southeast, and that has some suggesting a tipping point has been reached.

“I suspect” Florida will soon rival New York as a finance hub, Leon Cooperman, the hedge fund manager who founded New York-based Omega Advisors, told Business Insider in an email. “‘Tax and spend’ has been [the northeast’s] policy. It has to change or New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut will become ghost towns.”

It's not as if the business would not be welcomed: Florida needs solid jobs that are not so dependent on the tourist industry. But we do not need more people who are interested in making Florida into a second New York.

I lived in Upstate New York for much of my life, and recall well the division between New York City and the rest of the state, with the large-population City tail largely wagging the State dog. Hence New York's high taxes, strong unions, and onerous gun laws. Florida is in a similar situation, with the Miami/Palm Beach area being worlds apart from most of the rest of the state. If a large influx of New Yorkers comes to that part of the state hoping for more freedom, a better tax situation, and a lower cost of living, they'll find them—but if they bring with them the same attitudes that have led to the troubles they are fleeing, then we will all lose.

We have a friend who one year visited us from New York for the express purpose of trying to influence Florida's elections. His company was welcome, but I tell you, I'm a lot more worried about that than about whatever the Russians might be doing via our social media.

When we joined one of our previous churches, the pastor explained, "You do not have to agree with us to be welcome here. We only ask one thing: don't try to change us. If you feel the need to change our culture, you are released from your membership vows and are free to find another church that may be a better fit for you." When push came to shove, that's not exactly how it worked out, but the theory made sense to me.

I know whereof I speak. When we moved to Florida from New York more than 35 years ago, I was the quintessential Northeastern snob. It took me several years to realize that Florida was not (and is not) the backwards, ignorant place my prejudice had led me to believe.

I still miss New York and the Northeast. I especially miss great apples and unpasteurized cider. But the solution is not to plant apple trees here in Florida, but to appreciate citrus trees and unpasteurized orange juice. And to visit the places we have left behind.

We need to let Florida be Florida, New York be New York, Texas be Texas, and Montana be Montana. Just as Europe is realizing that they must not give up French, Norwegian, and Dutch culture for the sake of the European Union, we need to work for the United States to be united while remaining individual states. If we allow ourselves to become a homogenized monoculture, I can just about guarantee it will not give us the best of everything, but the worst—or if we're lucky, mediocrity.

Florida taught me that. Do you think you know what orange juice tastes like? What you buy in the store, even "fresh squeezed," is taken apart, put (somewhat) back together, cooked (pasteurized), and deliberately made so that every carton of orange juice tastes the same as every other. You haven't really tasted orange juice until you drink it raw, without all the processing, and with flavors that change as the season progresses and different varieties of orange go into the juice.

Florida does not need to be pasteurized and homogenized. I don't mean there aren't areas in which we can improve. But there's a huge difference between working for change from inside a culture you love, and running roughshod over a community to which you have fled, without regard for the local population. Cultural imperialism is no more palatable than any other kind.

So come, New York refugees. Live here, grow here, become Floridians. But don't bring New York with you. When I want to experience New York culture, I'll take a vacation there.

Permalink | Read 1349 times | Comments (1)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I'm certain Facebook had no idea what it was doing when it banned my 9/11 memorial post. Suddenly I started looking into others who claimed unfair and unreasonable censorship, people I had previously ignored. Contrary to what I had been led to believe, I have yet to find anything extremist, evil, hateful, or even particularly objectionable—certainly nothing as egregious as other offenses that Facebook seems to have no problem with. What I've seen has been at worst annoying. Of course I find things I disagree with (what else is new?) but also a lot that is interesting, reasonable, and fits with the world as I know it. Nothing, that is, that could justify Facebook's censorship.

I doubt that Facebook's intent in banning certain content was to inspire me to investigate that content, but that's not an unusual reaction. Ban a book or a movie and you generate interest in what would probably have died an ignoble death on its own. Were it not that platforms like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and such are so massive, and virtual monopolies, I would be less concerned.

Here's just one example. Even if the following video were not about censorship, it would be amazing, as I have never before been fascinated by legal language.

David Freiheit is a Canadian lawyer who gave up litigation for full-time video commentary on current issues from a legal standpoint. From what little I've seen of his YouTube channel, his style is a little on the crazy side, but he makes legal issues and legal documents interesting, which qualifies him as a miracle worker as far as I'm concerned.

Two things particularly struck me in watching this. The first is that I had no idea how lucrative Facebook advertising can be—the advertising that I generally ignore. For me, Facebook is a place for communicating with family—or friends, since most of my family has now deserted the platform—and I ignore the larger picture. But there's another world out there, a world of high finance, a world where there are worse consequences for offending the Facebook gods than having your post deleted. Can you even imagine a world where Facebook can demonetize your post, which takes away the percentage of ad revenue that you normally receive, and thus cost you over a million dollars a month?

Secondly, I was unaware of the practice of not just cutting off, but actually stealing that ad revenue. If I have an ad-revenue contract with Facebook, and they delete my post, I merely lose the income. But if they leave the post up, and merely demonetize it, they can still run ads—but Facebook (YouTube, whatever) gets all the revenue, rather than having to share it with the content provider. In other words, by determining that your content is somehow "wrong" they can take for themselves all the ad revenue the post generates.

This is from my understanding of the process, not from the video below. What the video adds is the idea that the "independent fact checkers," in determining that a post is "false," themselves benefit by doing so, since they can include links to their own content and funnel income from the original content poster to themselves, which is a huge conflict of interest and a positive incentive to label something as false. I get that one would want to be able to click to the reasoning behind such a label, but at the very least the fact-checkers should not profit from it. Anyway, if you have 23 minutes and are curious as to how legalese can possibly be interesting, here it is.

Permalink | Read 1231 times | Comments (1)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Robert Heinlein wrote that the Year of the Jackpot was 1952. It's a pity he died in 1988, because he would have loved 2020.

In one of those serendipitous Internet moments, I recently came across the answer to a puzzle that has been nagging at me for months. Longer, really.

Every time I'd shake my head and say, "The world has gone completely insane"—which I have been doing a lot this century—I'd remember a science fiction story from my distant past. I couldn't recall the title, the author, nor enough of the plot to begin to find it, though I tried halfheartedly now and again.

Then it was handed to me on a platter, in the form of a notification from eReaderIQ that a book from an author I'm following (Robert Heinlein) was on sale for 99 cents. It was called The Year of the Jackpot and is in reality a short story, not a book. You can read it for free right here, at the Internet Archive.

I knew as soon as soon as I saw the title that this was the story I had been remembering. Heinlein is a mixed author: some of his works are brilliant and delightful, others quite frankly off-the-rails unpleasant. This one is not a happy tale, but it is fascinating and enjoyable.

Here's one of my favorite paragraphs:

He listed stock market prices, rainfall, wheat futures, but the "silly season" items were what fascinated him. To be sure, some humans were always doing silly things—but at what point had prime damfoolishness become commonplace? When, for example, had the zombie-like professional models become accepted ideals of American womanhood? What were the gradations between National Cancer Week and National Athlete's Foot Week? On what day had the American people finally taken leave of horse sense?

Pretty mild compared with the decades-long "silly season" we're in now, isn't it? But the ending, well....

Potiphar Breen is a statistician whose hobby is charting cycles. And in the year 1952 they are not looking good at all.

Permalink | Read 1266 times | Comments (2)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I've been having fun cleaning out computer files, and came upon some old photos that may me wonder just how much our personalities are determined at birth or very early in our childhoods.

.jpg)

Here I am at age five, drinking water after enjoying a hike in the Adirondacks, wearing comfortable clothes and not sitting cross-legged. Comfort remains my highest criterion for choosing clothing, I have always loved spending time in the woods, water is my beverage of choice, and I have never, ever been able to sit cross-legged without serious discomfort.

Here's evidence from age six that my mother did her best to nurture my feminine side and teach me to be a proper young lady of the times. It didn't take. You can see by the expression on my face my heroic struggle to endure privation and torture for completely unfathomable reasons. Nothing has changed.

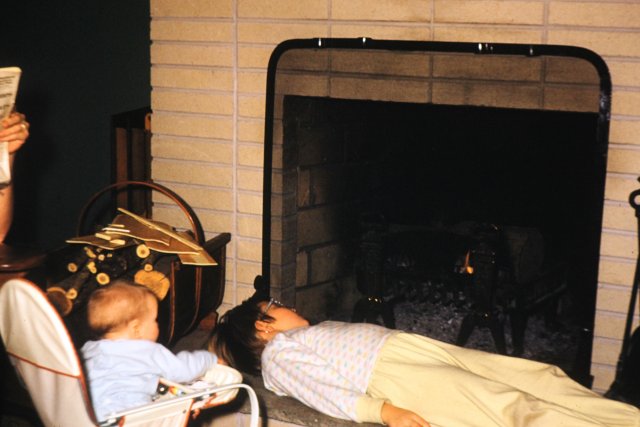

As a young mother, Thanksgiving at my in-laws' place in Moncks Corner, South Carolina, usually found me collapsed on the hearth in front of a comforting fire. This picture from Christmas at my grandparents' house in Rochester, New York shows that when I was seven I felt much the same way.

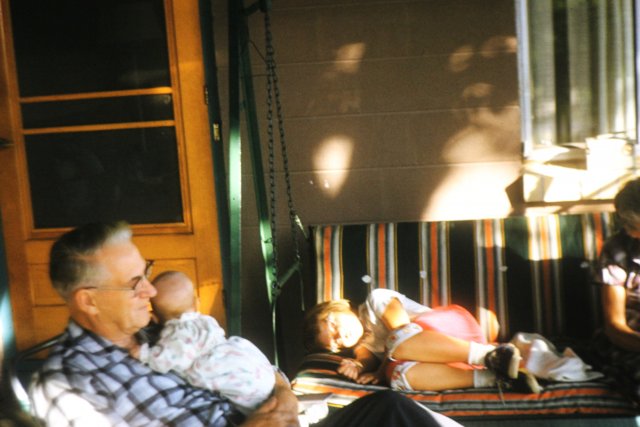

When this swing was new, it graced my grandfather's house. When he moved in with my family in Pennsylvania, the swing came with him. That particular swing is gone now, but when Porter found one for all practical purposes identical at our local Lowes, I had to have one for our Florida back porch. North or south, for more than 60 years I have found it one of the most comfortable places ever to sit, rock, read, think ... and sleep.

I don't mean we can't change. Nature vs. Nurture should no longer be a debate, since the answer is so clearly "both/and." But it still surprises me when I come across evidence—in myself and others—that many of our present characteristics were manifested very early on, if we'd had the eyes to see. Mostly it's fascinating; it only becomes depressing when I look back and realize I'm still fighting battles it seems I ought to have long since conquered and moved on.

So I wonder: Should we, as parents, be more alert to problems in our children that could lead to trouble in the future, and deal with them, rather than letting them slide and hoping they'll outgrow them? If so, which ones are manifestly bad and need eliminating (e.g. lying, laziness, disobedience), and which ones are just part of what makes us individuals (such as a need for solitude, a sensitive nature, or a very logical mind), in which case our job is to help the child both take advantage of the good and develop coping strategies for the bad?

Permalink | Read 1613 times | Comments (2)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Those of us who lived through what I think of as the "Carter Inflation" have a deep-seated fear of that economic disaster, and a greater fear that more recent generations don't take it seriously enough. (To be fair to President Carter, presidents get more blame and take more credit than they deserve for economic conditions. I think Carter, a good man, was a bad president with policies that made inflation worse, but it's far from exclusively his fault.)

Inflation under Carter was not a disaster for us, personally, since it was a time when salaries and investment income appeared to be increasing at a great rate. That felt good, though it only meant that we were barely keeping up with rising prices. It was not so merciful to people without good jobs and investments. We also knew enough history to fear the devastation inflation had caused in other times and places.

You might understand, then, why am frustrated when I hear reports of "inflation indices" that say we are experiencing little or no inflation—when I know darn well that prices in the grocery store have been rising steadily for a long time, most "half-gallon" ice cream packages now hold only three pints, and the price of automobiles has exploded through the roof.

I read with interest the article by John Mauldin called "Nose Blind to Inflation." It's long and gets complicated and I did start skimming as I neared the end, but it says a lot about the factors that go into determining a currency's inflation rate—and why it's so hard to come up with numbers that mean anything at all. As my economist husband says, it is important to understand that inflation is not a mathematically provable number, but rather a statistically, approximated number. Moreover, the numbers that are published are not immune to political pressure.

I'm not even going to try to guess what is going to happen to our currency now that the pandemic has encouraged us to hemorrhage money that we don't have and drive our national debt well beyond the stratosphere. Far more knowledgeable people than I haven't a clue.

But I can't resist one quote from the article, which begins the section on an inflation calculation factor called hedonic adjustment.

That’s where they modify the price change because the product you buy today is of higher quality than the one they measured in the past.

This is most evident in technology. The kind of computer I used back in the 1980s cost about $4,000. The one I have now, on which I do similar work (writing) was about $1,600. So, my computer costs dropped 40%. But no, today’s computer isn’t remotely comparable to my first one. It is easily a thousand times more powerful. So the price for that much computing power has dropped much more than 60%. It’s probably 99.9%.

The economists pull the same slight of hand with automobiles, and television sets, and any product in which it is claimed that you are getting more value for your money, and therefore it shouldn't count as a price increase. Which is utter nonsense. (I put the point a little more strongly when I first read about the concept.)

Sure, I often like the "improvements" that have supposedly added value to the item I am purchasing, but the real value of a car is that it gets me from A to B, and why must I pay for all the extra bells and whistles if that's all I want? It reminds me of a housing developer I know, who was chided for not providing more "affordable housing." "I could make housing affordable for everyone," he replied, "If people were willing to live in the kind of homes their grandparents did. But now that won't even begin to pass code."

So sure, go ahead and make things "new and improved." But if I can no longer buy the original version, don't try to sell me the bill of goods that when the price goes up it's really a price decrease.

This is for our children, and others of later generations who may find it difficult to fathom how great was the pressure on my generation to have no more than two (and preferably fewer) children. It was real. I'm ashamed to have given in, but it was the sea in which we all swam; it was the unquestioned Science of the day; it was the Way Things Were Done. It's a true story that some people would pray for multiples the second time around, so they could have more than two children and still be held blameless. ("Selective reduction" was not a thing back then.) Moreover, I was less inclined to fight against the tide of my peers back then—we who came of age in the late 60's and early 70's were too busy concentrating on pushing back against those who had come before us.

The following is extracted from a George Friedman Geopolitical Futures essay, "Variations on Apocalypse," published February 13 of this year. He nails the sentiment of the times—which lasted long beyond the supposed apocalypse year of 1970—exactly.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s there was an intense belief held by the best minds that humanity was on the eve of destruction. Rock music was written with this title. The cause of this catastrophe was overpopulation. By 1970, the Club of Rome, a highly respected gathering of the best and brightest, said the world would no longer be able to feed itself and would be running out of natural resources. Unless humanity repented of the sin of reproduction, it would annihilate itself. This was a belief that could not be challenged, and those who said not only that it was untrue but that the birthrate would soon plummet were dismissed. The coming apocalypse was written in stone, and those who would challenge it either were mad or would profit from the apocalypse.

What always struck me about this, and virtually every class I took included at least one lecture on this, was that those who argued the apocalyptic view were not actually frightened by it. They loved the role of Jeremiah. They awaited it with the faith of the righteous and, I suspect, were looking forward to the last moment, when they could scream, "I told you so."

It's easy to see one's past mistakes, but much, much more difficult to discern which of today's "certainties" we will be regretting in the future. I haven't a clue, but I suspect that the first place to look should be among (1) ideas and practices that are so much a part of our own culture—meaning primarily the culture of our peers—that we never think to question them; (2) ideas and practices for which dissent is discouraged, mocked, or even forbidden; and especially (3) ideas and practices that make us feel morally superior to others.

Permalink | Read 1313 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Facebook banned my 9/11 tribute post on the grounds that it violates their Community Standards. Fortunately, I'm the censor here.

Permalink | Read 1036 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Recently I stumbled upon The Conservative Student's Survival Guide. It's a five-minute video offering advice to—you guessed it—conservative students who find themselves a despised minority on liberal college campuses. That's no joke: for all the talk you'll hear from academia about tolerance, liberal values, and minority rights, it's a jungle out there if your particular minority isn't currently in favor, and it seems the only status more dangerous than "conservative student" on most American campuses is "conservative faculty." It was true when we were in college, it was true when our children were in college—and everything I see leads me to believe the situation is far, far worse now.

What's surprising about this video is that, unlike much that comes from both Left and Right these days, it is calm, well-reasoned, and respectful. What's more, even though it's aimed at conservative students, any thoughtful person who wants to make the most of his college experience would do well to consider this advice.

The speaker is Matthew Woessner, a Penn State political science professor. All of his seven suggestions make sense, but my top three are these:

- Avoid pointless ideological battles. It's not your job to convert your professors or your fellow students. Discuss and debate, but don't push too hard.

- Choose [your classes and your major] wisely. I was a liberal atheist in college, but much on campus was too far Left even for me. Being a student of the hard sciences saved me from a great deal of the insanity that was going on in the humanities and social sciences departments. A quarter-century later, one of our daughters found some of the same relief as an engineering major. Our other daughter, however, discovered that life at a music conservatory was quite difficult—despite the name, conservative values were not welcome.

- Work hard—college faculty value hard-working, enthusiastic students. I'd say this is the most valuable of all his points. Excellence and enthusiasm are attractive. A student who participates respectfully in class, does the work, and learns the material will gain the respect and appreciation of most of his professors. Teachers are like that.

A friend recently posted a sign which said, "Trump took ... the united out of the United States."

The illogical falseness of that statement jumped out at me, and believe me, my friend is smart, so I know she must also have seen it. Most memes of that sort aren't even trying to be logical; they're trying to make a point.

Nonetheless, my first reaction was to ... react. To respond with a comment.

Then I remembered that I am fed up with arguing, and am trying a new approach.

When I comment on someone else's blog, or social media post, I am stepping into his space and time. Would I ring my neighbor's doorbell and tell him, "I see you're getting your house painted; that's a terrible color!" I think I can do better than that. If I have no positive comment to make, much better I should say nothing at all. That doesn't mean I'm going to stop commenting—I know myself too well for that—but I hope to be more positive, more relevant, and more personal when I do, conscious that I am walking through someone else's yard.

My own space, however, is a different story. Here, on my blog, or on my own Facebook page—that's where my own opinions belong. If people find my posts interesting, or helpful, I'm glad. If they do not, they are free to walk away. When I first began writing this blog, I had hopes that it would become (among other things) a forum for debate and discussion of issues. Now that I've seen what that looks like on Facebook, I'm rather glad it mostly has not. The more experience I have, the more I realize that people long for information, and can be persuaded by information—especially when accompanied by personal testimony—but are rarely moved, except possibly in the opposite direction, by argument and debate. Maybe it wasn't always so, but it certainly is now.

Back to the original inspiration for this post: the idea that President Trump had divided America. I think that's completely wrong.

The election of President Trump, if you will, is evidence that America is divided. All close elections are. When you win a close election, the first thing you should realize is that half of the country is unhappy about your victory. Even should you win an astonishing 75% of the vote, you still will have ticked off a quarter of the voters.

America has always been a country of deeply-felt and deeply-divided opinions. Even a small study of history—in my case, genealogy—makes that obvious. The difference now, as I see it, is that instead of expressing our opinions to a few neighbors, we tell them to the world.

As I do here.

Perhaps I am as guilty as President Trump of dividing America.

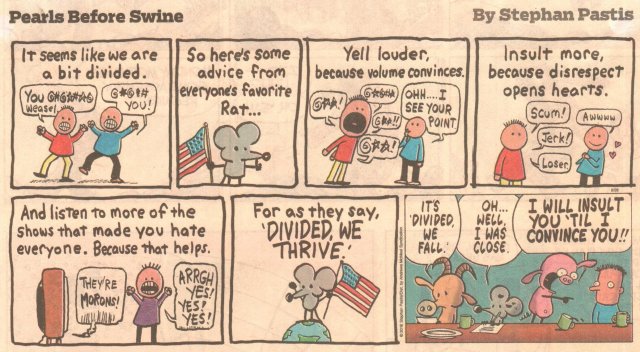

Here's a Pearls Before Swine comic, from August 26, 2018, still appropriate to the day. (Straight from our refrigerator to you.)

Permalink | Read 1398 times | Comments (1)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I think America owes ISIS an apology. We were so self-righteous over their destruction of ancient monuments—sometimes more upset by that than by their destruction of people. Now we are doing it ourselves. If the history isn't as old as in the Middle East, it's the same abominable impulse.

That's as heavy as this post is going to get. On the lighter side, here is a word for our modern iconoclasts from Psalm 105, at least as interpreted by Sunday's church bulletin.

Permalink | Read 1191 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

It was written in 1992 and set in 1145, but the situation discussed in these excerpts from Ellis Peters' The Holy Thief—part of her Brother Cadfael series—sounds as fresh as this morning's dawn.

Robert Bossu This has become a war which cannot be won or lost. Victory and defeat have become alike impossible. Unfortunately it may take several years yet before most men begin to understand. We who are trying to ride two horses know it already.

Hugh Beringar If there is no winning and no losing, there has to be another way. No land can continue for ever in a chaotic stalemate between two exhausted forces.

Robert It has gone on too long, and it will go on some years yet, make no mistake. But there is no ending that way.

Hugh What does a sane man do while he's enduring such waiting as he can endure?

Robert Tills his own ground, shepherds his own flock, mends his own fences, and sharpens his own sword.

Hugh Collects his own revenues? And pays his own dues?

Robert Both. To the last penny. And keeps his own counsel. Even while terms like traitor and turncoat are being bandied about like arrows finding random marks.

Permalink | Read 1391 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

As I neared the end of my C. S. Lewis retrospective—reading (mostly re-reading) all the books we own by or about the prolific author—I was challenged by my friend, The Occasional CEO, to relate a few of the most significant things I have learned from Lewis. I began with the idea of trying to distill a Top Five from his many areas of influence in my life.

It soon became clear that of everything I have learned from Lewis—from faith to literature to history to the changing meaning of words to the critical importance of one's model of the universe—two stood out, orders of magnitude greater than the rest.

All is gift. I am Oyarsa not by His gift alone but by our foster mother’s, not by hers alone but by yours, not by yours alone but my wife’s—nay, in some sort, by gift of the very beasts and birds. Through many hands, enriched with many different kinds of love and labor, the gift comes to me. It is the Law. The best fruits are plucked for each by some hand that is not his own.” (Perelandra)

The first gift I received from C. S. Lewis was his Narnia stories. I was introduced to them in mid-elementary school: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe was a gift from my mother, who brought it to me in a stack of books from the library when I was sick in bed. The remainder of the series came about two years later, a gift from a neighbor, who owned all seven and shared them around our group of friends. I was delighted, enthralled. However, my attempt to find similar delight in his other fiction was at the time unsuccessful. I tried the first of his Space Trilogy, but I was a hard-core science fiction fan—Asimov, Heinlein, Clarke—and Out of the Silent Planet was not sufficiently science-based for me. One of Lewis's earliest books, it lacks the beauty and enchantment of the Narnia stories, and was intended for an adult audience. I have since come to enjoy it, but I wasn't ready then.

I rediscovered Narnia in college, thanks to the University of Rochester's Education Library, which was well-stocked with children's books. There I also first encountered Mere Christianity: the gift of my roommate, and my introduction to Lewis's nonfiction. To my shock, there I discovered that all the delight—the goodness, truth, and beauty—that I had encountered in Narnia was for Lewis an expression of reality, a reality far greater than he could depict, even in fantasy. I came later to respect the background in Christianity I had received in my childhood, but it was through Lewis and Narnia that the reality of God began to make sense to me.

This is the first and great gift, and the second is like unto it.

I went on to read more of Lewis's non-fiction, and to gain from it, but his next pivotal gift came many years later, through a friend—all is gift—who shared with me Lewis's George MacDonald: An Anthology.

If Narnia had shown me a God who made sense of the world, MacDonald showed me a God I could love.

George MacDonald is another author I had met before—as a child through his Curdie books and At the Back of the North Wind—but I'd never followed through to find what else he might have written. To be fair to myself, his other books weren't easy to find back then.

Of MacDonald, Lewis wrote,

In making these extracts I have been concerned with MacDonald not as a writer but as a Christian teacher. If I were to deal with him as a writer, a man of letters, I should be faced with a difficult critical problem. If we define Literature as an art whose medium is words, then certainly MacDonald has no place in its first rank—perhaps not even in its second. There are indeed passages, many of them in this collection, where the wisdom and (I would dare to call it) the holiness that are in him triumph over and even burn away the baser elements in his style: the expression becomes precise, weighty, economic; acquires a cutting edge. But he does not maintain this level for long. The texture of his writing as a whole is undistinguished, at times fumbling. Bad pulpit traditions cling to it; there is sometimes a nonconformist verbosity, sometimes an old Scotch weakness for florid ornament (it runs right through them from Dunbar to the Waverly Novels), sometimes an oversweetness picked up from Novalis. But this does not quite dispose of him even for the literary critic. What he does best is fantasy—fantasy that hovers between the allegorical and the mythopoeic. And this, in my opinion, he does better than any man. (Unless otherwise noted, all quotations are from Lewis's preface to George MacDonald, An Anthology.)

MacDonald's works can be divided roughly into three parts, though they overlap: the fantasy that so impressed Lewis; books of sermons; and his many adult novels—the craft of which left Lewis so unimpressed—which served both to feed his family of thirteen and as vehicles for reaching a wider audience with his preaching. The last sounds dreary, but in reality the preaching is what makes his novels shine. (Those who know my lack of appreciation for most sermons will recognize the peculiarity of such a statement coming from me.)

Having been reawakened to MacDonald by Lewis's Anthology, I looked around for more, and the best I could find were modern re-workings of his novels, some by Michael R. Phillips and some by Dan Hamilton. I give credit to both authors for their obvious respect for MacDonald, and their faithfulness to his ideas, even though in their efforts they exaggerated the parts I like least from the originals (the Romantic elements) and reduced the best (the preaching). The library had most of them, and I wolfed them down.

Most of my extracts are taken from the three volumes of Unspoken Sermons. My own debt to this book is almost as great as one man can owe to another.

The next contributor to my journey was a church secretary who had obtained photocopies of all three Unspoken Sermons books, which she graciously shared. I wonder if the generations who grew up with easy access to a universe of electronic resources can even imagine how valuable bound photocopies could be. Or what an incredible gift it was to the world when, in the 1990's, Johannesen began republishing all of MacDonald's works, in beautifully-crafted sets. All of these treasures were given to me, over several years of birthdays and Christmases, by my father. He himself had no particular appreciation of MacDonald—I doubt he read any of the books—but a great deal of love for his children and grandchildren, for whom I consider the collection a legacy. Now, Kindle versions of almost all of MacDonald's works are available at no cost.

I have never concealed the fact that I regarded him as my master; indeed I fancy I have never written a book in which I did not quote from him.

Lewis is not exaggerating the frequency of MacDonald's influence on his own works. Having tackled my MacDonald retrospective first, I easily recognized his ideas and often his words when I encountered them in Lewis.

I know nothing that gives me such a feeling of spiritual healing, of being washed, as to read George MacDonald. (from a letter of Lewis to Arthur Greeves)

I dare not say that he is never in error; but to speak plainly I know hardly any other writer who seems to be closer, or more continually close, to the Spirit of Christ Himself.

What greater endorsement could there be?

Lewis was puzzled as to how people could idolize him and ignore MacDonald. I have some ideas. MacDonald's books were old, even then—he had died before Lewis turned seven—and our society's "chronological snobbery" was well established. Although full of gold, many of his books are difficult to read, even those not laden with Scottish dialect. I can now say that it's well worth the effort, and the reading and understanding get much easier with practice. But I can't forget that I had actually encountered MacDonald's novels years before, deep in the stacks of our main college library. But apparently this, too, had to wait to be a gift rather than my own choice: to my everlasting embarrassment, I turned aside from those unattractive, ancient, brown, and dusty tomes. Perhaps it was the library's revenge that I later became a genealogist, whose blood now quickens at the mere scent of such books.

Then, too, from the beginning MacDonald was plagued by charges of heresy and branded "Universalist" for his belief that, in the end, God's love would triumph. Lewis did not see him that way, but it led (and still leads) some to dismiss MacDonald out of hand.

Reaction against early [strict Scottish Calvinist] teachings might ... have very easily driven him into a shallow liberalism. But it does not. He hopes, indeed, that all men will be saved; but that is because he hopes that all will repent.

Nowhere else outside the New Testament have I found terror and comfort so intertwined.

Inexorability—but never the inexorability of anything less than love—runs through [MacDonald's thought] like a refrain; "escape is hopeless"—"agree quickly with your adversary"—"compulsion waits behind"—"the uttermost farthing will be exacted." Yet this urgency never becomes shrill. All the sermons are suffused with a spirit of love and wonder which prevents it from doing so. MacDonald shows God threatening, but (as Jeremy Taylor says) "He threatens terrible things if we will not be happy."

The effect of C. S. Lewis's writings on my thinking is incalculable, and not just from his most popular books. Who would have guessed, for example, that I would give a five-star rating to Studies in Words—a book on philology, addressed to scholars, of which I understood less than half? But I was fascinated, and my eyes were opened to the pernicious habit (especially common among both literary critics and high school English teachers) of simply seeking meaning in what we read, instead of seeking what the author meant by his words and what his contemporary audience understood him to be saying.

There's no doubt that Lewis was quirky, humble, and absolutely brilliant—all the more brilliant that so many of his writings were written to be accessible to the ordinary British public, yet there's no hint of condescension. I could start my Lewis retrospective over again from the beginning and learn a lot more.

But for all that, Lewis's greatest influence on my life came less through my mind than through my spirit. Lewis said that reading MacDonald's Phantastes "baptized his imagination." The Narnia books first, and then George MacDonald directly, did the same for me.

This surprising realization came nearly sixty years after my first encounter with The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, and was itself a gift—thanks to my friend's challenge.

I think maybe this confinement is getting to me. It's not that I particularly miss going out, though I do really miss the good times we had getting together with other people. I love being home and have more work to do here than I could complete in a hundred pandemics. But I really miss church activities, and two opportunities have already slid by in which we would normally have gotten together with far-away family. At least two more are threatened. We have missed one wedding and are hanging onto hope for another. Our grandchildren have grown and changed so much since we saw them last! The year of 2020 will be the first year since 2005 I have not travelled out of the country to be with family.

I know, I know. Before anyone says it, I know we're still blessed beyond measure and I honestly expect much good to come out of this pandemic. Much already has.

And yet it's invading my dreams.

I love to be outside very early in the morning. Every day I go out to our back porch swing, and listen. I listen to the insects and the frogs, and to the armadillo as he waddles back to his den after his nocturnal adventures. I listen to the barred owls, and to the songbirds when they awaken. Though I don't listen for them, I can't help hearing the traffic noises, pool pumps, and air conditioner compressors. I listen to my own thoughts, and then struggle to still them and listen for the whispering voice of God. Sometimes, in my listening, I fall back to sleep, as I did today. And today I dreamed.

In my dream, I was also dozing. Not on the porch, but in our family room; I must have been doing some work using my computer and my phone, for they were both there with me. In my dream I awoke, and all was changed. Every window had been boarded up, as we sometimes do when a hurricane is approaching. (Clearly Isaias had also found its way into my dreaming.) But instead of plywood, this was cement board—and unbreakable. And it was not just the windows that were boarded up, but all the doors.

In my dream, I was also dozing. Not on the porch, but in our family room; I must have been doing some work using my computer and my phone, for they were both there with me. In my dream I awoke, and all was changed. Every window had been boarded up, as we sometimes do when a hurricane is approaching. (Clearly Isaias had also found its way into my dreaming.) But instead of plywood, this was cement board—and unbreakable. And it was not just the windows that were boarded up, but all the doors.

We were completely shut in. There was no way out. There was no view out. Between one moment and the next, we had been cut off from the world outside.

What caused me the most distress was the back door. I couldn't stop looking at the cement board blocking what should have been a green, leafy view. Then somehow—the details are vague—a small view opened up so that I could see into the back yard. Gone were the trees, the plants, the insects, the frogs and the birds. In place of the porch, pool, and yard was a vast expanse of concrete with a single exercise trampoline off to one side, and a bulldozer off to the other.

Still half-asleep, I struggled to think. My computer and my phone were no more responsive than my thoughts. Finally, a little girl's voice asked, "Are we just going to watch the paint dry?"

Still fighting to come to full consciousness in my dream, I awoke to a like struggle to come out of what must have been a very deep sleep. But there I was on my swing, on our porch, with the blue of the pool and the green of the foliage in front of me. Dawn had come, and the birds were singing.

Permalink | Read 1507 times | Comments (2)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

After reading the Occasional CEO's post on Moxie (My favorite line? "Moxie is the durian of carbonated drinks."), I was inspired to write about my favorite New England carbonated drink, Undina Birch Beer from Higganum, Connecticut. I'm not generally a fan of carbonated drinks, nor of alcohol for that matter, but this white birch beer, with its 1% alcohol content, was exceptional. And nothing like the darker birch beers I had tasted in other parts of the country.

This Haddam Historical Society webpage has a small section, "Granite Rock Springs/Undina Soda," on the Undina Beverage Company and their white birch beer.

In the 1870’s Otto Carlson started making commercial root beer and birch beer in Swede Hill (upper part of Christian Hill Road) in Higganum. Carlson had a nostalgic longing for a drink remembered from his boyhood in Sweden, ‘bjord drick’ made from sap tapped from Sweden’s prolific birch trees. Not having enough birch trees around Higganum for commercial scale tapping, Otto developed a formula using cut up birch trees and steaming out their oils and juices. This became the commonly used commercial method of producing the popular birch beer.

Who knew white birch beer was Swedish? With all the Swedes on Porter's side of the family, it's no wonder the drink was a favorite. Sure seems a shame to cut up a tree to get it, though. Maybe we can have commerical birch groves for tapping like maple trees.

Needing a large quantity of water for his company, Carlson discovered a large bubbling spring in a cleft of granite rocks on the western slope of Ladder Pole Mountain in Higganum. This was “pure spring water,” above and beyond any possible contamination. Granite Rock Springs was 450 feet above sea level, up hill from Otto’s shop and overlooking the present Route 81. Otto Carlson named his beverage company UNDINA, meaning the Goddess of Water.

A write up on the spring notes that the “no part of its watershed is exposed to the seepage of cultivated fields or the impurities of inhabited areas. Its home is in the wild heart of nature and it gushes forth, a living, crystal clear stream of pure, soft water, a stream so large as to form the source of a mountain brook that is never dry but continually leaps and dances down the mountain-side until its waters finally join those of the Connecticut.

This delightful spring was used to make their white birch beer until 1980, when production outstripped its capacity. I could tell you that I noticed the difference, but that's probably stretching memory too far.

In the early 1900’s Undina was a popular brand of soda pop, with white birch beer its most popular flavor. Undina was distributed throughout Middlesex County and other parts of Connecticut and upstate New York. ... In 1945 Undina Beverage Company was purchased by Carl Anderson of Higganum and Eric Johnson, both of whom also remembered the cool refreshing ‘bjord drick’ in Sweden and took pride in maintaining production of the white clear drink.

Still Swedish!

By the 1950’s Undina Bottling Works was thriving and producing 500 cases of soda per day. It remained at the same site as Carlson’s original shop, although the extraction was no longer done there. In 1960 the company was purchased by Middletown residents Trean Neag and Fred Norton.

No longer Swedish except in origin. (Neag was Romanian; Norton I couldn't trace back far enough to find out.) The American Melting Pot in action!

The article doesn't mention when Undina closed. It was after our children were old enough to fall in love with their white birch beer, but much too long ago to pass that on to their own children. It sure was a sad day when they closed. I've heard that it lasted till Fred Norton retired; I'm sure the economics of running a small, local business in the days of soda behemoths contributed to its demise.

Perhaps now that microbreweries have become so popular and successful, someone will attempt to revive Undina. I hope so. You can still buy white birch beer if you try hard enough, and I'm grateful for that. But of course it's not the same.