Are you shocked that Bill Cosby is now free? I was, but now that I know more about the circumstances, I'd be shocked if he weren't.

I'm not one to follow the high-profile prosecutions, especially of celebrities, that are so popular in the news media. I know I'm unusual in not having watched a single minute of the O. J. Simpson trial, for example. Call me weird, but I see no reason to put myself in the position of mentally convicting or acquitting the person being tried unless I'm actually on the jury and have all the legally relevant information.

It is, however, impossible to avoid all the publicity that comes with such trials, and Bill Cosby was familiar to me because of his comedy sketches when I was young. I had a few of his records. I still quote some of his lines, e.g. "Hey, you! Almost-a-doctor!" from the story of getting his tonsils out (15 minutes).

If anyone is shocked that I would publish one of Cosby's works "after what he did," I say that great works have been done by terrible people, and if we reject everything based on the sins of the workers in other areas of life, we won't have a whole lot left.

Be that as it may, the issue isn't Cosby's comedy but his trial, which was a long story, to which, as I said, I didn't pay much attention. When I heard that the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania had thrown out his conviction, my immediate, ignorant, reaction was, "another criminal released on a stupid technicality!"

Not exactly. Viva Frei explains it well here (14 minutes).

If you'd rather not watch the video, the short version, as I understand it—and I certainly don't claim to know the laws—is that the district attorney had decided that he did not have a strong enough case against Cosby to expect a conviction, and that by not pursuing a criminal trial he would make it more likely that the alleged victim would get justice in civil proceedings. Which apparently she did, thanks to the fact that Cosby, freed from the fear of prosecution, made some pretty damning confessions in the civil trial. However, when a new district attorney took over, he did not feel himself bound by his predecessor's decision, and went ahead and prosecuted Cosby, using his civil testimony against him, and thus obtained a conviction. Apparently "pleading the Fifth Amendment" is reserved for criminal cases, and one can be forced to self-incriminate in civil cases. Who knew? The trial court judge allowed this to happen, having decided that there was no "real" agreement between the former DA and Cosby that should tie their hands.

Here is a very small part of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court's decision:

Starting with D.A. Castor's inducement, Cosby gave up a fundamental constitutional right, was compelled to participate in a civil case after losing that right, testified against his own interests, weakened his position there and ultimately settled the case for a large sum of money, was tried twice in criminal court, was convicted, and has served several years in prison. All of this started with D. A. Castor's compulsion of Cosby's reliance upon a public proclamation that Cosby would not be prosecuted. ... There is only one remedy that can completely restore Cosby to the status quo ante. He must be discharged, and any future prosecution on these particular charges must be barred. ... A contrary result would be patently untenable. It would violate long-cherished principles of fundamental fairness. It would be antithetical to, and corrosive of, the integrity and functionality of the criminal justice system that we strive to maintain.

In other words, the end does not justify the means. A result cannot be just if it is obtained by cheating. As my attorney friend—who has served much time on both prosecution and defense—tells me, even the worst criminal deserves the benefit of the law. It's time to pull out A Man for All Seasons again (5 minutes).

Much as we might not like it, the same rights and rules that protect us also protect criminals. The First Amendment has the same "problem."

Permalink | Read 1272 times | Comments (1)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

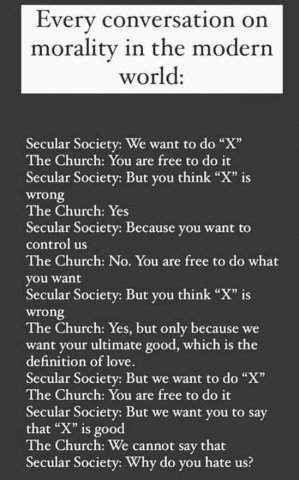

Memes are today's proverbs: None is perfect for every situation, but good ones speak truth clearly and efficiently. This is a good one.

Permalink | Read 1079 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Butterflies don't look back at the caterpillar with shame.

Stop looking at your past with shame.

It was a transformation and it brought you here.

I saw this yesterday on a friend's Facebook page. I'm not going to spend any time analyzing it, but use it as the perfect introduction to these cute little guys, who with their companions are devouring our substantial parsley bush.

They're welcome to it. Not because we don't like parsley—we certainly do—but because these babies are pre-transformation swallowtail butterflies.

We get monarchs every year, but haven't had swallowtails since 2018.

Permalink | Read 1218 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Courage is not simply one of the virtues but the form of every virtue at the testing point.

— C. S. Lewis, in The Screwtape Letters

Permalink | Read 1154 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Last Battle: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Lawyers aren't very popular among the people I know, and even in general are more often maligned and mocked than almost any group of people—except maybe dead white males. I am one of those who frequently rail against lawyers because our increasingly litigious society has robbed us of the ability to make rational risk/benefit assessments, be it in childrearing, schools, medical decisions, playground equipment, government regulations, corporate policy, or almost anything else.

There certainly are bad actors in law, as there are in any field of endeavor. Perhaps the legal profession is at more risk of this than most, given the combination of great power and lots of money to be made. But following the Viva Frei vlawg (law-themed video blog) has made me aware of a very important truth:

The only way to fight bad lawyers is with good lawyers.

It is perilous to mock the professions that stand between us and the disintegration of society, from the policeman on his beat to the Supreme Court justice. That we do so reflects the relative security of our lives—a high form of privilege.

This video (11 minutes), one of several chronicling the defamation lawsuit of Project Veritas against the New York Times, illustrates how lengthy, difficult, and often tedious the process has become. A few bad apples aside, maybe lawyers are earning their hefty fees after all.

Yesterday's video (16 minutes) has an update to the case—the next tedious step—which you can see by clicking on that link. I chose to embed the earlier one as more illustrative, and especially because of the quotation at the end, from George MacDonald, one of my favorite authors. I tend to fast forward over the repetitious stuff after the main story, instead of merely closing the video, because I almost always like David Freiheit's choice of quotations at the very end. In this video, MacDonald is slightly misquoted, but the meaning is unchanged. The correct version, from The Marquis of Lossie, is below.

To be trusted is a greater compliment than to be loved.

Permalink | Read 1232 times | Comments (1)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

"Who Is in Control? The Need to Rein in Big Tech," from this past January's Imprimis magazine, deserves mention here. It's not one I would normally republish, not because I don't agree with it, but because the author is the senior technology correspondent for Breitbart News. He has the credentials to be heard, but Breitbart's biases make me as wary as CNN's do, and I know many of my left-leaning readers would see that and stop reading.

Don't. Please don't. What he has to say about the uncontrolled power of Google, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Amazon, and the like should concern everyone. Right now, it's conservatives who are feeling the flex of Big Tech's muscles, but the tech leaders could easily turn around and bite the hands that are currently feeding them. If you believe in freedom and democracy at all, this is worth reading and pondering.

Like most Europeans, my son-in-law, who is Swiss as well as American, has always wondered why I am so afraid of the misuse of governmental power, and not concerned about Google. I, in turn, don't understand how he can be so worried about tech companies while having no problem with a level of government surveillance and interference that would shock most Americans. I still think he's wrong not to be worried about excessive power in governmental hands, but I have to admit that he's right about Big Tech.

My response used to be, "Who cares if Google uses my data to target ads? I just ignore them, as I've always done with ads in newspapers (I usually don't even notice them) and on television." But that was then. That was before Facebook took down my 9/11 memorial post because it included a photo of Saddam Hussein. That was before it became obvious that Facebook was troubled by posts that even hinted that they might be about COVID-19. (Click image to enlarge.)

That was before I noticed how much Facebook and YouTube censor viewpoints they don't like. How careful one must be not to run afoul of their "algorithms." And certainly before Facebook, Twitter, Google, and Amazon proved that they are powerful enough to shut down the president of the United States, as well as a service (Parler) that welcomed Donald Trump's participation.

This may look as if it's about politics. It's not. It's about power. And it threatens everyone on every part of the political spectrum.

In January, when every major Silicon Valley tech company permanently banned the President of the United States from its platform, there was a backlash around the world. One after another, government and party leaders—many of them ideologically opposed to the policies of President Trump—raised their voices against the power and arrogance of the American tech giants. These included the President of Mexico, the Chancellor of Germany, the government of Poland, ministers in the French and Australian governments, the neoliberal center-right bloc in the European Parliament, the national populist bloc in the European Parliament, the leader of the Russian opposition ... and the Russian government.

Common threats create strange bedfellows. Socialists, conservatives, nationalists, neoliberals, autocrats, and anti-autocrats may not agree on much, but they all recognize that the tech giants have accumulated far too much power. None like the idea that a pack of American hipsters in Silicon Valley can, at any moment, cut off their digital lines of communication.

It is important to remember that the Web, as we know it today—a network of websites accessed through browsers—was not the first online service ever created. In the 1990s, Sir Timothy Berners-Lee invented the technology that underpins websites and web browsers, creating the Web as we know it today. But there were other online services, some of which predated Berners-Lee’s invention. Corporations like CompuServe and Prodigy ran their own online networks in the 1990s—networks that were separate from the Web and had access points that were different from web browsers. These privately-owned networks were open to the public, but CompuServe and Prodigy owned every bit of information on them and could kick people off their networks for any reason.

...[T]he Web was different. No one owned it, owned the information on it, or could kick anyone off. That was the idea, at least, before the Web was captured by a handful of corporations.

We all know their names: Google, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Amazon. Like Prodigy and CompuServe back in the ’90s, they own everything on their platforms, and they have the police power over what can be said and who can participate. But it matters a lot more today than it did in the ’90s. Back then, very few people used online services. Today everyone uses them—it is practically impossible not to use them. Businesses depend on them. News publishers depend on them. Politicians and political activists depend on them. And crucially, citizens depend on them for information.

Ah, the early days. We were early Prodigy users, and GEnie, before the Internet took off. Those were the days when it was easy to interact with famous people, because it was all so new and the numbers were small. GEnie's Education RoundTable was a great resource in our early days of homeschooling, and there I met Bobbi Pournelle, wife of science fiction writer Jerry Pournelle. We even arranged to meet when she came to Orlando, as did other of my ERT acquaintances. That was before we were warned against having meet-ups with people we only knew online, and it was a good deal of fun.

Big Tech has become the most powerful election-influencing machine in American history. It is not an exaggeration to say that if the technologies of Silicon Valley are allowed to develop to their fullest extent, without any oversight or checks and balances, then we will never have another free and fair election. But the power of Big Tech goes beyond the manipulation of political behavior. As one of my Facebook sources told me ... “We have thousands of people on the platform who have gone from far right to center in the past year, so we can build a model from those people and try to make everyone else on the right follow the same path.” Let that sink in. They don’t just want to control information or even voting behavior—they want to manipulate people’s worldview.

Consider “quality ratings.” Every Big Tech platform has some version of this, though some of them use different names. The quality rating is what determines what appears at the top of your search results, or your Twitter or Facebook feed, etc. It’s a numerical value based on what Big Tech’s algorithms determine in terms of “quality.” In the past, this score was determined by criteria that were somewhat objective: if a website or post contained viruses, malware, spam, or copyrighted material, that would negatively impact its quality score. If a video or post was gaining in popularity, the quality score would increase. Fair enough. Over the past several years, however—and one can trace the beginning of the change to Donald Trump’s victory in 2016—Big Tech has introduced all sorts of new criteria into the mix that determines quality scores. Today, the algorithms on Google and Facebook have been trained to detect “hate speech,” “misinformation,” and “authoritative” (as opposed to “non-authoritative”) sources. Algorithms analyze a user’s network, so that whatever users follow on social media—e.g., “non-authoritative” news outlets—affects the user’s quality score. Algorithms also detect the use of language frowned on by Big Tech—e.g.,“illegal immigrant” (bad) in place of “undocumented immigrant” (good)—and adjust quality scores accordingly. And so on.This is not to say that you are informed of this or that you can look up your quality score. All of this happens invisibly. It is Silicon Valley’s version of the social credit system overseen by the Chinese Communist Party. As in China, if you defy the values of the ruling elite or challenge narratives that the elite labels “authoritative,” your score will be reduced and your voice suppressed. And it will happen silently, without your knowledge.

If Big Tech’s capabilities are allowed to develop unchecked and unregulated, these companies will eventually have the power not only to suppress existing political movements, but to anticipate and prevent the emergence of new ones. This would mean the end of democracy as we know it, because it would place us forever under the thumb of an unaccountable oligarchy.

The author does have a suggestion, and I think it sounds reasonable. (I know my audience will not hesitate to let me know if I've missed something.) Some may think that I am against government regulation, but that's not true. I'm against unreasonable government regulation. (For my purposes, I get to define "unreasonable.") Most especially I am against regulations that fail to distinguish between large entities (in business, agriculture, education, medicine, and the like) and the small and individual. I don't know how to quantify "large enough" to need special regulation, but I have no doubt that our tech giants have crossed that line.

All of Big Tech’s power comes from their content filters—the filters on “hate speech,” the filters on “misinformation,” the filters that distinguish “authoritative” from “non-authoritative” sources, etc. Right now these filters are switched on by default. We as individuals can’t turn them off. But it doesn’t have to be that way. The most important demand we can make of lawmakers and regulators is that Big Tech be forbidden from activating these filters without our knowledge and consent. They should be prohibited from doing this—and even from nudging us to turn on a filter—under penalty of losing their Section 230 immunity as publishers of third party content. This policy should be strictly enforced, and it should extend even to seemingly nonpolitical filters like relevance and popularity. Anything less opens the door to manipulation.

I cannot say it strongly enough: This is not a left-wing thing; this is not a right-wing thing. This is a big thing. A thing we must all come to grips with.

Thinking further about Cal Newport's Deep Work, here are two more valuable quotations I should have included.

First, on the importance of a "shutdown ritual" for ending the "work day" (however that is defined for us) and not letting it take over the rest of our lives. I see it as less about employment and more about being able to switch cleanly from one activity to another (including rest).

The concept of a shutdown ritual might at first seem extreme, but there's a good reason for it: the Zeigarnik effect. This effect ... describes the ability of incomplete tasks to dominate our attention. It tells us that if you simply stop whatever you are doing at five p.m. and declare, "I'm done with work until tomorrow," you'll likely struggle to keep your mind clear of professional issues, as the many obligations left unresolved in your mind will, as in Bluma Zeigarnik's experiments, keep battling for your attention throughout the evening.

At first, this challenge might seem unresolvable. As any busy knowledge worker can attest, there are always tasks left incomplete. The idea that you can ever reach a point where all your obligations are handled is a fantasy. Fortunately, we don't need to complete a task to get it off our minds. ... In [a study by Roy Baumeister and E. J. Masicampo], the two researchers began by replicating the Zeigarnik effect in their subjects (in this case, the researchers assigned a task and then cruelly engineered interruptions), but then found that they could significantly reduce the effect's impact by asking the subjects, soon after the interruption, to make a plan for how they would later complete the incomplete task. To quote the paper: "Committing to a specific plan for a goal may therefore not only facilitate attainment of the goal but may also free cognitive resources for other pursuits."

The shutdown ritual ... leverages this tactic to battle the Zeigarnik effect. While it doesn't force you to explicitly identify a plan for every single task in your task list (a burdensome requirement), it does force you to capture every task in a common list, and then review these tasks before making a plan for the next day. This ritual ensures that no task will be forgotten: Each will be reviewed daily and tackled when the time is appropriate. Your mind, in other words, is released from its duty to keep track of these obligations at every moment—your shutdown ritual has taken over that responsibility. (pp. 152-154, emphasis mine).

I find I need to re-learn the following every day.

The science writer Winifred Gallagher stumbled onto a connection between attention and happiness after an unexpected and terrifying event, a cancer diagnosis. ... [A]s she walked away from the hospital after the diagnosis she formed a sudden and strong intuition: "This disease wanted to monopolize my attention, but as much as possible, I would focus on my life instead." The cancer treatment that followed was exhausting and terrible, but Gallagher couldn't help noticing, in that corner of her brain honed by a career in nonfiction writing, that her commitment to focus on what was good in her life—"movies, walks, and a 6:30 martini"—worked surprisingly well. Her life during this period should have been mired in fear and pity, but it was instead, she noted, often quite pleasant. Her curiosity piqued, Gallagher set out to better understand the role that attention—that is, what we choose to focus on and what we choose to ignore—plays in defining the quality of our life. After five years of science reporting, she came away convinced that she was witness to a "grand unified theory" of the mind:

Like fingers pointing to the moon, other diverse disciplines from anthropology to education, behavioral economics to family counseling, similarly suggest that the skillful management of attention is the sine qua non of the good life and the key to improving virtually every aspect of your experience.

This concept upends the way most people think about their subjective experience of life. We tend to place a lot of emphasis on our circumstances, assuming that what happens to us (or fails to happen) determines how we feel. From this perspective, the small-scale details of how you spend your day aren't that important, because what matters are the large-scale outcomes, such as whether or not you get a promotion or move to that nicer apartment. ... [D]ecades of research contradict this understanding. Our brains instead construct our worldview based on what we pay attention to. If you focus on a cancer diagnosis, you and your life become unhappy and dark, but if you focus instead on an evening martini, you and your life become more pleasant—even though the circumstances in both scenarios are the same. As Gallagher summarizes: "Who you are, what you think, feel, and do, what you love—is the sum of what you focus on." (p. 76-77, emphasis mine).

I don't write these posts to frighten or depress anyone. But a number of my readers have higher priorities than chasing down news stories, so I like to raise awareness when I come upon something important, interesting, or even just fun. This one's not fun, but it is important.

Why should I care what's happening in Canada? Leave aside for the moment that Canadians, too, are human beings made in the image of God and therefore we should care about them, and that Canada is the huge neighbor covering our entire northern border and one of our major allies. We should also care about what's happening with our near neighbor because the United States is not as far from this creeping danger as we might like to think.

One of our daughters and several of our grandchildren have for years been taking lessons in karate. One thing I have learned from them is that the first, and possibly the most important, key to self-defense is awareness of your surroundings. Never forget that a far better source also proclaimed wisdom as an essential accompaniment to innocence.

Half a century ago our family discovered Ontario's Arrowhead Provincial Park. We had only intended to spend one night there on our way to Michigan, but were so enchanted we stayed for three. It was quite primitive at the time: there wasn't much to do, and the bathroom "facilities" were a latrine. But we were almost alone in the park; most of the other tourists were staying in nearby Algonquin Provincial Park, which was more developed and very popular. Never have I breathed air so clean and invigorating. More memorable than that, however, were the stars. Not in all the rest of my life have I seen such a display, and such a show, as we lay on our backs on a huge woodpile and watched shooting stars streak across the sky at a rate of perhaps one every two or three minutes. I knew then that if I couldn't live in the United States, I'd want to go to Canada. Later Switzerland moved ahead, and that was well before we had family living there. But Canada stayed a solid second.

Well, that was then and this is now. There are many reasons why Canada has slipped far down on my list, but the following video would be enough.

A government (Ontario's, in this case) went too far with its pandemic restrictions, and finally the citizens—including medical practitioners and the police—rebelled, forcing the leaders to back down on the most egregious of the new rules. That's good news, but be sure to watch to the end to see the clips of Ontario's authorities and their "this hurts me more than it hurts you but it's for your own good" act. And their "it's your duty to snitch on your neighbors" response.

Ontario is a province of 14.5 million people, and 650 of them are currently in intensive care units. This minuscule percentage has caused such panic that the provincial government's response was (among other things) to issue a stay-at-home order, to close playgrounds, boat ramps, and other outdoor recreational activities, and to authorize law enforcement to stop and interrogate any people caught outside of their homes. Canada takes enforcement of these rules very seriously: the fine for violating Quebec's 8 p.m. to 5 a.m. curfew, for example, starts at $1500.

Part of the problem is that Canada's health infrastructure is not good. An ordinary flu season overwhelms the ICUs. I've known for years that Canada's healthcare system is broken, despite the fact that it has its passionate defenders. (Much of my information comes from Canadian nurses, who fled to the U.S., bringing horror stories with them.) Even a bad system—healthcare, government, business, church, marriage—can look reasonable when times are good. It's times of crisis, pressure, and stress that reveal the truth and call into account the leaders we have elected (or been saddled with).

I used to look at historical happenings in other countries—e.g. Austria-Hungary 1914, pre-WWII Germany, Communist Eastern Europe, the Rwandan genocide—and smugly think, "That could never happen here, not now." However, the past year has shown that it can, indeed, happen here and now. We're not there yet, but we've come a lot closer, particularly in the area of what ordinary citizens will do to their neighbors.

American has no call to feel smug—or safe. We may not be as far down the road as Canada is, but it sure looks as if we are heading in the same direction. Should we panic? Despair? Absolutely not. But we'd darn well better be paying attention.

Do you see a man skilful in his work? he will stand before kings - Proverbs 22:29 (RSV)

Excellence is almost always a joy to behold. A well-crafted piece of furniture, a musical performance of great artistry, a fabulous meal, a well-run business, an amazing athletic feat—I think we are hard-wired to find great skill attractive. Something done well is not necessarily something worth doing, and it is all too easy to value the wrong things simply because they are excellently done. But the excellence itself is good.

I'm sure we could all be better at whatever we do, if we would only put enough time and focused effort into it. If we don't find that possible, or desirable, however, there's another attractive factor that can fill in some of the gaps: Enthusiasm. Often something merely "good enough," if approached with passion, can be delightful. Not always: Florence Foster Jenkins comes to mind, but even she had famous admirers and once sold out Carnegie Hall.

Passion for a subject often encourages hard work, long hours, and perseverance, which in turn can take native talent to greatness. When excellence and enthusiasm meet, the result is attractive indeed.

This is why I sometimes find myself really enjoying YouTube videos covering subjects in which I have previously had little to no interest. You'll see some of them in an upcoming series of posts featuring channels to which I've recently subscribed. The usual caveats apply: I like to make available to others books, articles, and videos I have found to be of some value, even if I don't agree with everything presented. Your mileage may vary. Take what is helpful to you; leave the rest.

I may not agree with, or even understand, all that I see and hear, but I love the skill and passion with which it is presented.

Permalink | Read 1372 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Last week the air conditioning came on; today we are back to heating. That's Florida Spring for you. One day you sleep with the ceiling fans awhirl; the next you are very glad you haven't gotten around to putting away the extra blankets.

Snce I love the cooler weather, I'm not sorry for its return. Of course, that's "cooler" as in mid-40's lows, and mid-70's highs, which qualifies as a warm spring day where I spent my childhood. :)

Anything lower than that might discourage the blossoming citrus trees, whose heavenly odor is one of my favorite signs of Florida Spring.

Permalink | Read 1103 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

O. J. Simpson, Casey Anthony, George Zimmerman, Donald Trump ... pick your favorite villain. There's someone out there who you are certain "got away with murder." It rankles, doesn't it? Makes you doubt our system of justice. Me? I'm just as guilty, though I worry more about the uncounted criminals who "get off on a technicality" when everyone involved knows they're guilty—including their own attorneys.

In the court of public opinion, we are all vigilantes. And that's a problem.

We have a lawyer friend who has seen our criminal justice system from several angles, having served for years as a prosecuting attorney, and for years as a defense attorney. I well remember a somewhat heated discussion with him, which started when I mentioned that I like the British system, in which a defense attorney, if he becomes convinced his client is guilty, must step down. (As I understand it, that was at least the case in the past. For all I know it might have changed.) Our friend is a gentle, mild-mannered man, but he vehemently disagreed, insisting that even the most guilty person is entitled to the best possible defense his attorney can provide. Maybe that's why the British attorneys stand down, figuring they can't do their best if they believe their client guilty. Apparently American defense lawyers have no such inhibitions. At least not the good ones.

All that to say, when a lawyer takes on what we believe to be the "wrong" side of a case, that doesn't make him a villain. And when a jury returns a verdict we disagree with, that doesn't make them wrong. They're all doing their jobs, and vitally important jobs they are.

In litigation, sometimes even when you win, you still lose. — David Freiheit.

In the American justice system, one does not need to be proven innocent to be acquitted. Because "innocent until proven guilty" is a bedrock principle, the burden of proof is on the prosecutor, who must show the accused to be guilty "beyond reasonable doubt." Small wonder that We the People, inflamed by media coverage, believe we know better than those who have seen the evidence and heard the arguments. We want to see our version of justice done without any respect for or patience with the due process guaranteed every one of us. Yes, the system sometimes fails, sometimes makes mistakes; I've seen it fail among our own family and friends. But vigilante "justice" is a terrifying prospect. It's time to reprise A Man for All Seasons again.

Current society is taking vigilantism to new heights. It's long been true that many of those found not guilty in law courts have nonetheless had their lives ruined (or even ended) by the opposite verdict from the court of public opinion. Now, however, the "String him up!" reaction extends not simply to the former defendant, but even to his attorney, as you can see in the following video.

If you are thinking of becoming a lawyer, and you are so sensitive to the thoughts of others that you sometimes require protection from them, you probably want to find a new line of work. — David Freiheit.

I never had aspirations of becoming a lawyer; I don't think I have the right personality. But even I can see that what this unnamed law school did to attorney David Schoen—rescinding a teaching offer in fear that Schoen's previous job as an attorney for President Trump would make some students and faculty feel uncomfortable—is doing a tremendous disservice to the students they hope to prepare for legal practice. Not to mention to society as a whole. Don't take my word for it; Freiheit says it better.

People don't seem to fully appreciate how dangerous a practice this actually is. — David Freiheit.

Remember what I said in my recent review of Nineteen Eighty-Four?

Most of the analyses I read online consider the climax of the book to be where Winston Smith and Julia betray each other. It seems clear to me, however, that the true climax occurs much earlier in the book, when they believe they are joining the Brotherhood, an organization dedicated to opposing the ruling Party.

"In general terms, what are you prepared to do?"

"Anything that we are capable of," said Winston.

O'Brien had turned himself a little in his chair so that he was facing Winston. He almost ignored Julia, seeming to take it for granted that Winston could speak for her. For a moment the lids flitted down over his eyes. He began asking his questions in a low, expressionless voice, as though this were a routine, a sort of catechism, most of whose answers were known to him already.

"Yes."

"You are prepared to commit murder?"

"Yes."

"To commit acts of sabotage which may cause the death of hundreds of innocent people?"

"Yes."

"To betray your country to foreign powers?"

"Yes."

"You are prepared to cheat, to forge, to blackmail, to corrupt the minds of children, to distribute habit-forming drugs, to encourage prostitution, to disseminate venereal diseases—to do anything which is likely to cause demoralization and weaken the power of the Party?"

"Yes."

"If, for example, it would somehow serve our interests to throw sulphuric acid in a child's face—are you prepared to do that?"

"Yes."At that point any hope for the future is lost, those opposing evil having shown themselves to be no better than their opponents. Everything after that is dénouement.

That.

As a young child, I received an allowance of 25 cents a week. (A quarter was worth a lot more 'way back then.) From that I was expected to allocate some to spend as I pleased, some for the offering at church, and some to be saved into my small account at the bank. That was the beginning. My family had a culture of saving, as well as giving and spending. Saving was for the future—for larger-ticket items, and for unknown future needs.

Part of the excellent advice I received from my father as I was establishing my own household was to set up a regular savings plan, not only for future purchases but to ensure that I could handle at least a six-month period of unemployment—preferably a full year. Of course it took some time to save that much money when I had all the expenses of newly-independent living to meet, but by making it a priority I soon had a comfortable cushion against unexpected expenses.

Fortunately, I married a man with similar views, which were not uncommon among those of us whose parents had lived through the Depression days. For a number of years we were blessed with two incomes, but made a point of keeping our standard of living low enough that we could live on one and save the other. This stood us in very good stead when disaster hit the American information technology industry, and so many IT workers lost their jobs because the work was transferred to India and other places overseas.

But somewhere along the line the culture of saving was largely lost. Once considered a virtue, saving is now called "hoarding" and held in contempt. It seems to be considered a patriotic duty to spend all one's money—and more. (If true, we have been bleeding red, white, and blue during this pandemic.) However, the ugly consequences of this attitude are nowhere more apparent than in the large numbers of families facing financial disaster due to pandemic-related job loss. So many people have gone in the blink of an eye from enjoying comfortable incomes to standing in bread lines. If they had been encouraged to follow my father's advice and maintain a savings cushion of a year's salary, they would likely have been able to weather this storm with ease. But no one—not the government, not the media, not the schools, not our consumerist society, and apparently far too few parents—has been passing on this essential lesson.

I hope it won't take another Great Depression to recover our lost wisdom.

Permalink | Read 1267 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Mister Rogers' Neighborhood was pretty much the only children's television program seen in our house when our children were growing up. Not regularly, but occasionally, and we had several on videotape that were watched many times over. Unrelated, but interesting, is the fact that our children performed at least once in the Fred Rogers room at Rollins College, and one of them attended college in Pittsburgh and met Mister Rogers himself.

Fred Roger's legacy is enduring, and his calm, gentle, positive shows are even now being rediscovered by yet another, supposedly worldly-wise and jaded generation.

Yet I have to ask: What happens when the children grow up?

Suddenly their world is filled with people who do not like them "just the way they are"—angry, judgemental people who are quick to find fault, to mock, to sneer, and to revile. Suddenly how they look, how they think, what they believe, and how they vote sets them up as targets. Love and safety have disappeared. Mistakes are no longer seen as acceptible learning opportunities Even their Neighborhood of Make-Believe has turned dark, tragic, and frightening.

Grownups need Mister Rogers' Neighborhoods, too.

Permalink | Read 1303 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

This is not my own, but the person I learned it from can't remember where she first found it. And it's not a direct quotation, because I've modified it to sound better in my own ears. But the sentiment is exactly the same.

"A writer is a writer not because he has amazing talent. A writer is a writer because, even when nothing he does shows any sign of promise, he keeps on writing anyway."