Yes, there is something good to be found in television. The signal-to-noise ratio may be terrible, but there's good, too, and today's Memorial Day post was inspired by two shows I saw parts of recently. If the people I honor today didn't give their lives in service to their country, they certainly gave much of their lives to that service.

The first honored the WASPS of World War II, the Women's Airforce Service Pilots, whose courageous story, and our country's shameful response, has finally been told. For too long the first female American military pilots were not only denied veteran's benefits but treated as if their service had never existed. The battle for recognition was a long, slow process, though it kicked into high gear when the military began touting a much-later set of women as the first. You know that an injustice has been done when a cause for which conservative Senator Barry Goldwater fought so strenuously was later acknowledged as right by President Barack Obama. You can see the trailer at this link; I haven't managed to embed it here. Nor does it work for me in Firefox, but it did in Chrome.

The second show mentioned the Hump pilots, also of World War II, and the gratitude the Chinese people still feel towards them. Naturally I thought of Colonel William Bryan Westfall, Hump pilot and veteran of World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. I never met him, as he died before his grandson married our daughter, but I'm grateful to him, for his remarkable military service—and for his family legacy.

Happy Memorial Day to all, and Whit Monday as well, for those of you privileged to live where that holiday is honored, even if its meaning, like that of Memorial Day, is often lost except as an excuse to celebrate.

Permalink | Read 2220 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Disclaimer: I don't know who Matt Walsh is, although a quick search revealed that he is making enough waves that there's a website called whatismattwalshwrongabouttoday.com. That's okay; if people feel the need to attack him, he's probably doing something right, and in any case, he gets this one really, really right: “You’re a stay-at-home mom? What do you DO all day?” (H/T Jon) This husband's homage to his wife was inspired by conversations like the following:

“So is your wife staying at home permanently?”

“Permanently? Well, for the foreseeable future she will be raising the kids full time, yes.”

“Yeah, mine is 14 now. But I’ve had a career the whole time as well. I can’t imagine being a stay at home mom. I would get so antsy. [Giggles] What does she DO all day?”

“Oh, just absolutely everything. What do you do all day?”

“…Me? Ha! I WORK!”

“My wife never stops working. Meanwhile, it’s the middle of the afternoon and we’re both at a coffee shop. I’m sure my wife would love to have time to sit down and drink a coffee. It’s nice to get a break, isn’t it?”

The conversation ended less amicably than it began.

Walsh's whole commentary is worth reading. Here are some snippets.

Look, I don’t cast aspersions on women who work outside of the home. I understand that many of them are forced into it because they are single mothers, or because one income simply isn’t enough to meet the financial needs of their family. Or they just choose to work because that’s what they want to do. Fine. I also understand that most “professional” women aren’t rude, pompous and smug, like the two I met recently. ... But I don’t want to sing Kumbaya right now. I want to kick our backwards, materialistic society in the shins and say, “GET YOUR FREAKING HEAD ON STRAIGHT, SOCIETY.”

In making his point, the author fails to mention that there are other essential professions (sometimes lacking in respect), and that any legitimate work done with excellence and integrity has value, often great value. Cut him (and me) some slack: it doesn't change the truth of what he says. Our society has elevated employment, almost any employment, over work that does not bring in a paycheck, especially if the non-paying work involves home and family, like rearing children or caring for elderly parents.

It’s true — being a mom isn’t a “job.” A job is something you do for part of the day and then stop doing. You get a paycheck. You have unions and benefits and break rooms. I’ve had many jobs; it’s nothing spectacular or mystical. I don’t quite understand why we’ve elevated “the workforce” to this hallowed status. Where do we get our idea of it? The Communist Manifesto? Having a job is necessary for some — it is for me — but it isn’t liberating or empowering. Whatever your job is — you are expendable. You are a number. You are a calculation. You are a servant. You can be replaced, and you will be replaced eventually. Am I being harsh? No, I’m being someone who has a job. I’m being real. ... If your mother quit her role as mother, entire lives would be turned upside down; society would suffer greatly. The ripples of that tragedy would be felt for generations. If she quit her job as a computer analyst, she’d be replaced in four days and nobody would care.

Having been both computer analyst and mother, I can attest to what he says. Guess which career garnered the most admiration and accolades?

Of course not all women can be at home full time. It’s one thing to acknowledge that; it’s quite another to paint it as the ideal. To call it the ideal, is to claim that children IDEALLY would spend LESS time around their mothers. This is madness. Pure madness. It isn’t ideal, and it isn’t neutral. The more time a mother can spend raising her kids, the better. The better for them, the better for their souls, the better for the community, the better for humanity. Period.

The following may be my favorite paragraph of the whole article.

Finally, it’s probably true that stay at home moms have some down time. People who work outside the home have down time, too. In fact, there are many, many jobs that consist primarily of down time, with little spurts of menial activity strewn throughout. In any case, I’m not looking to get into a fight about who is “busier.” We seem to value our time so little, that we find our worth based on how little of it we have. In other words, we’ve idolized “being busy,” and confused it with being “important.” You can be busy but unimportant, just as you can be important but not busy. I don’t know who is busiest, and I don’t care. It doesn’t matter. I think it’s safe to say that none of us are as busy as we think we are; and however busy we actually are, it’s more than we need to be.

I think I'll change my advice to those who are asked the condescending and offensive question, "What do you DO all day?" And I'd apply it to almost any profession, not just motherhood—no one from the outside can really know what it takes to do another's job. First, I'd quote Elbert Hubbard: Never explain—your friends do not need it and your enemies will not believe you anyway. Then I'd suggest this as a response:

That's a trade secret, and revealing it is against the rules of our Guild.

Permalink | Read 2268 times | Comments (9)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

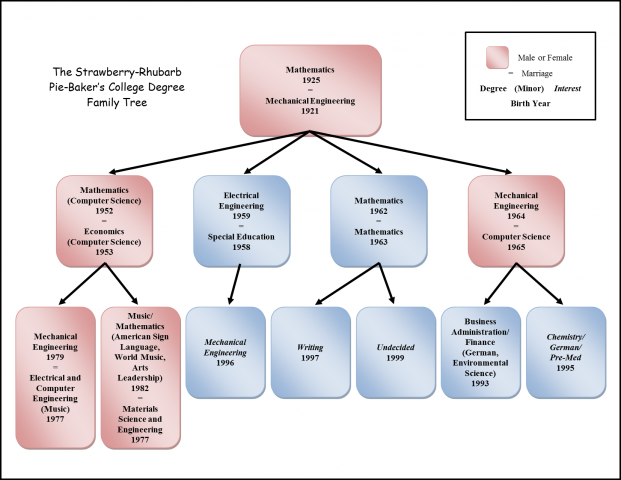

In the first comment to Saturday's Pi(e) post, Kathy Lewis asked about the math legacy of my mother (the one who introduced Kathy to strawberry-rhubarb pie). This inspired the genealogist in me to answer the question visually. (Click image to enlarge. Family members, please send me corrections as needed.)

Math-related fields clearly run in the family, by marriage as well as by blood. Some other facts of note:

- Most of the grandchildren (and all of the great-grandchildren, not shown in the chart) have not yet graduated from college. Their intended fields, where known, are shown in italics. One is very close to graduation, so I've left him unitalicised.

- In each generation from my parents through my children, there's been an even split between mathematics and engineering. However, with the next generation at nine and counting, I doubt that trend will continue.

- The other fields don't come out of nowhere: both of my parents had a vast range of interests.

- With one short-term exception in a time of need, every woman represented here clearly recognized motherhood as her primary and most important vocation, forsaking the money and prestige that come with outside employment to be able to attend full time to childrearing and making a good home. Every family must make its own choice between one good and another; this is not a judgement on other people's choices. Nonetheless, homemaking and motherhood as careers are seriously undervalued these days, so it's worth noting when such a cluster of women all choose to focus their considerable intelligence and education on the next generation. As daughter, wife, mother, aunt, and grandmother, I'm grateful for the choices these families (fathers as much as mothers) have made.

- Engineering is a long-time family heritage. My father's father (born 1896) was a mechanical engineer, and the first chairman of that department at Washington State University. His father (born 1854) was a civil engineer.

Permalink | Read 3270 times | Comments (6)

Category Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Genealogy: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

My nephews introduced me to Top Gear, the BBC show that achieved the astounding feat of making me thoroughly enjoy a show about ... automobiles.

Now the BBC has suspended co-host Jeremy Clarkson after a dust-up with a producer. Clarkson is no stranger to controversy and has been "warned" about previous behavior. This was apparently just the last straw for the folks at the BBC. From the Wikipedia article linked above:

Top Gear has often been criticised for content inside programmes.... Incidents and content ranging from (but not limited to) remarks considered by some viewers to be offensive, promoting irresponsible driving, ridiculing environmental issues, Germans, Mexicans, and Poles, and alleged homophobia have generated complaints. British comedian and guest of the programme Steve Coogan has criticised the programme, accusing it of lazy, adolescent humour and "casual racism".

Yep, Top Gear can be offensive. The show where they drive from Miami through the Deep South wasn't funny to me, as it was clear they were going out of their way to promote negative stereotypes about Americans, Floridians, and Southerners. (Few Floridians, except perhaps those in the Panhandle, consider themselves true Southerners.) Who in his right mind would drive through Florida in the summer, in a car without air conditioning, and be surprised that he was hot? And keep harping about it? What disappointed me the most—though I had suspected it from watching other shows—was that much of the action was clearly staged. I was certain in this case, because I know something about Florida. Had I been as knowledgeable about the sites of their other road trips, I'm sure I would have had similar complaints.

Most offensive of all was their attempt to get a 1960's-era Ku Klux Klan response as they drove through Alabama, or maybe it was Mississippi, I don't remember. They decorated their cars with signs and banners designed to offend their hosts, from in-your-face promotion of homosexuality, to insults to the region's dominant religion and to NASCAR. (And no, despite some evidence to the contrary, the last two are not the same thing.) Failing to get the desired, hateful response (they were mostly ignored), they went well off the main roads, and pushed harder, finally provoking a reaction—though I'm not entirely sure that wasn't staged as well.

So yes, sometimes parts of the show are over the top. And much of the humor is puerile. But that's the nature of the show. That's part of what attracts the viewers. They like the humor and the down-to-earth nature of the characters. I still enjoy Top Gear—I especially enjoy sharing it with my nephews—and I'm more easily offended than most when it comes to rudeness. The show is entertaining and informative despite its faults. And here's the problem I have with its producers: They know what sells, what the audience likes; they hire a man like Jeremy Clarkson who can pull it off; and when a little heat comes their way, they make him the scapegoat. They hire someone with rough edges, then self-righteously distance themselves from his lack of polish. It's like buying an axe and complaining that you hurt yourself trying to shave with it.

Why would I defend rude behavior? Partly because of the show's good qualities. Partly because Clarkson's offenses are minor compared with what others get away with. (Think talk radio, for one thing.) But mostly because the self-righteous hypocrisy of the BBC's thought police just sickens me.

Permalink | Read 2629 times | Comments (3)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

It's extraordinary how often otherwise civilized people think it's not only their right but their duty to criticize the size of other people's families. I freely confess to doing so myself on occasion, though I do try to limit my comments to general cases, not specific people. Maybe it's because the only remaining area of our sex lives where criticism has not been taken off the table is its fruit (or lack thereof).

Most annoying are the self-righteous critics. You know, the ones who insist that sweet little baby you just gave birth to will destroy the ecological balance of the world. Or those who praise God for the gift of antibiotics and other life-changing interventions while solemnly intoning that your use of birth control betrays your basic lack of trust in God's plan for your family. There are valid points lurking behind both of those extremes, but there is room for such a wide range of disagreement that prudence and courtesy—not to mention the love we owe our fellow human beings, and the good ol' Golden Rule—call us to admit that the size of other people's families is no one's business but their own.

That said, I recently found a Front Porch Republic article that explicates one of the negative side effects of the recent trend toward small families. I highly recommend reading the entire article, but will quote here as much as I think I can without raising the ire of the copyright fairies. (More)

I can see by yesterday's Frazz comic that Frazz lives in Connecticut or some other state that charges a few pennies extra for certain bottles and cans (mostly drink, such as soda and beer—but not water; I have yet to figure it all out), and then gives them back to you if you return the bottle to the grocery store.

What I still don't get about this system is, Why? I mean, I understood it when I was growing up, eons ago, because the bottles were reused. On the very rare occasions when we had beer or soda in the house, we were happy to return the bottles for the nickels they brought (five cents was worth a lot more back then), and so that the companies could refill them. We always put our empty milk bottles back out on the porch for the milkman to retrieve—not for money, but so that he would in turn leave us bottles full of (pasteurized, but not homogenized) milk.

But those days were long ago and far away. No one reuses bottles, and certainly not aluminum cans. I assume that they are all sent from the grocery store to a recycling center. Is a nickel, or even a dime, worth the effort of storing and returning the containers? The real value is in the recycling. The Swiss go through that effort because that's the way recycling is done there—there are no 5-rappen tips for doing what's right. In our town in Florida, we collect all recyclables in one bin which is then picked up at our homes weekly. It's as easy as throwing them in the trash.

The states that I know of that put a deposit on certain recyclables also have home recycling, so wouldn't the marginal cost of picking up all bottles and cans be almost nil? Why, then, do they continue the old practice?

Permalink | Read 2683 times | Comments (11)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Far be it from me to minimize the intelligence and contributions of Henry Louis Gates, Jr. My own feelings about him are mixed, as I think he acted irresponsibly and reprehensibly in the Cambridge Incident. Not his initial reaction—I wouldn't want to place any bets on my own rational behavior after returning from an exhausting overseas trip and finding myself locked out of my house, then being suspected by the police of housebreaking. But for escalating the affair even after the facts were known. At least I think that I, upon calmer reflection (and perhaps some much-needed sleep), would have been grateful to have had a neighbor notice that someone was jimmying my door, and police willing to be certain the housebreaker was who he said he was.

That aside, however, I can't deny his accomplishments, nor fail to appreciate his contributions to the genealogical field, especially in making it more popular and accessible to many who otherwise would never have given it a second thought. For a while we watched his PBS series, Finding Your Roots, though just as with Who Do You Think You Are? and Genealogy Road Show, it got tiresome after a while: too much hype, too many celebrities, not enough content. His work is serious, and his passion genuine.

Recently Gates was interviewed in the American Ancestors magazine published by the New England Historic Genealogical Society. His passion shows in his answer to the question, Where do you see genealogy in five or ten years? What do you think is going to happen?

I'm working with a team of geneticists and historians to create a curriculum for middle school and high school kids, to revolutionize how we teach American history and how we teach science using ancestry tracing. Every child in school would do a family tree. We think that's the best way—to have their DNA analyzed and learn how that process works in science class. In American history class, we think that's the best way to personalize American history and the nature of scholarly research. For a lot of kids, going to the archives, looking at the census is boring. But if we say, "You're going to learn about yourself, where you come from," what child wouldn't be interested in that?

Really? Really? I'm 100% with him on the idea that genealogy makes history personal and for me far more interesting. I can feel and appreciate his enthusiasm. But can you imagine parental reaction to this particular permission slip? This is several orders of magnitude greater than the privacy violations already imposed on families by the schools. Genetic genealogy is a very young science with innumerable risks and ethical pitfalls. Even those of us who value the genetic information available aren't necessarily thrilled with the idea of our genetic information being "out there."

Medical fears Who else can learn that I have a genetic predisposition to cancer, or bipolar disorder? If I get tested, will I be morally obligated to reveal the results to my family, my doctors, or on an insurance or employment application? Do I even want to know myself? If the school learns such a thing about my child, will that affect their treatment of him? Could they initiate a child abuse claim if we refuse to take whatever steps they recommend based on this knowledge?

Sociological and psychological fears A child discovering that his father isn't the man he has called Daddy all his life. A youthful indiscretion revealed by the discovery of an unexpected half-sibling. Decades-old adulteries brought to light. We like to hear of the DNA-testing success stories, of Holocaust survivors reunited with family members they thought long dead. But there's a darker side to the revelations: as one man wrote, With genetic testing, I gave my parents the gift of divorce. Even if we're certain there are no skeletons in our own closets, or don't care if they're brought to light, can we be so sure about other family members? Can we speak for their wishes? What's revealed about our DNA affects other lives; no man is a genealogical island.

Security fears I have too much respect for hackers and too many misgivings about the NSA to believe any reassurance that the data is secure. And indeed, much of the information desired by those who have their DNA analyzed is only useful if it is shared.

To be sure, there's a lot of very interesting data that can potentially be mined from DNA testing, and I'm not saying I'll never consent. It's tempting, to be sure. But it's not a decision to be entered into lightly, and certainly not one to be imposed on a family by a middle school history teacher. Even one as enthusiastic and as persuasive as Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

It takes a rich, greedy capitalist to grind the poor into the dust, right? Certainly over the years many have done a very good job of that. Our recent viewing of the documentary, Queen Victoria's Empire, drove home the disastrous consequences of both imperialism in Africa and the Industrial Revolution back home in Britain.

However, the same video also revealed the devastation that can be wrought by someone with good intentions, even against his will (e.g. David Livingstone), and especially when combined with the above-mentioned greed (e.g. Cecil Rhodes).

Which brings me to the point. I cannot count the hours and hours of struggle Porter has put into getting us health insurance in these post-retirement times. Without a doubt, I am personally grateful for the choices the Affordable Care Act (a.k.a. Obamacare) offers us, as much as I philosophically fear its negative consequences. Some of those negative consequences are personal, too: e.g. the colonoscopies that had been covered by our insurance in the past no longer qualify for coverage because of new rules instituted by the ACA. And we can't afford to get sick until after the end of January, because the "helpful" phone contact assigned us the wrong Primary Care Provider, and the fix won't go into effect till February 1. However, I admit to no longer hoping for repeal of the ACA, because the damage has been done. Too many people, including us, are now dependent on it. I doubt we can put the genie back in the bottle.

While I freely acknowledge that the passage of the ACA had at its heart noble ideals and good intentions, I'm not convinced it's really helping the poor, or at least not as much as it's helping people who get rich off the needs of the poor. Porter, being retired, has the time to put into navigating the complex and exceedingly frustrating waters. He also has a degree in economics and a mind well-suited to financial calculations. Which convinces me that the truly impoverished will (1) throw up their hands and settle for a much less than optimal health care plan, or (2) fall prey to those who would profit from doing the paperwork for them, while charging inordinate fees and still coming up with a less than optimal plan.

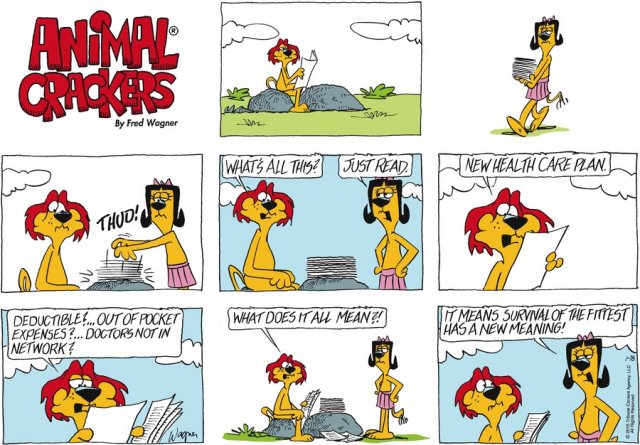

Nonetheless, the purpose of this post is neither to start a political discussion nor to depress you. It's to honor my husband, for whom Sunday's Animal Crackers comic could have been created:

No doubt about it: I married the right man.

Permalink | Read 3171 times | Comments (0)

Category Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The Battle of Kings Mountain was, like that of nearby Cowpens, decisive in turning the tide of the American Revolution in the South. Not that I was ever taught that in any history class in school, where local prejudice made the Battle of Saratoga the only "turning point of the American Revolution." But better half a century late than never: I know it now, and we visited both Kings Mountain and Cowpens on one of South Carolina's most beautiful ever November days.

Another point of major importance that I never knew: in the South, the Revolution was actually a civil war. Having been brought up in the Northeast, I never thought of Tories as being all that important: the Revolution was a battle between patriotic Americans and their nasty British overlords. But in this part of the land the fight was brother against brother, or at least neighbor against neighbor, with loyalties somewhat fluid, and more about personal freedom than politics and breakfast beverages. The British did their best to encourage the Loyalist faction (Tories) against the Patriots (Whigs), much as we keep trying to do in other countries today. They'd hoped to get the Americans to do most of the dirty work for them, remaining themselves in more of a leadership and advisory position. (Not much has changed in 234 years.) At Kings Mountain, the officer in charge of recruiting and leading the Loyalists was Patrick Ferguson. (More)

You may know the story, but still I dare you to watch this with a dry eye. It's well done, and worth watching the extras at the end, too. (H/T Diana)

Permalink | Read 2058 times | Comments (2)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

This Rochester Review letters page cheered us both considerably tonight. Mike Armstrong, brilliant computer guru at the University of Rochester Computing Center in our day, confesses to being overwhelmed by today's computing power. His letter ("Something Doesn't Compute" in about the middle of the page) is worth reading as a peek into the field's ancient history; we joined the game in the days of the IBM 360/65. But it was to the final paragraph that we could relate best:

But those were, to me, the good old days of wooden computers and iron programmers. When I left the Computing Center in 1980, I felt I knew the room-sized computer systems thoroughly, from the hardware to the operating systems and most of the application programs. Now I carry a small computer in my pocket that has more memory and more computing power than all of NASA’s computers when they put Neal [sic] Armstrong on the moon, and I have no idea how it works. And it also makes phone calls.

Permalink | Read 2133 times | Comments (1)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

My husband likes me to be with him, to look over his shoulder, while he works. I am exactly the opposite. With a few exceptions—such as when I want someone to "hold my hand" through an unfamiliar or difficult procedure—I hate it when someone watches me work. I fall apart. I trip over my feet, my fingers, my words. Simple tasks that I can do without thinking suddenly become nearly impossible. I become incompetent even in my areas of expertise.

Why? I never had a clue, until I read "The New Neuroscience of Choking" from the New Yorker of a couple of years ago. (Yes, it has been on my To Blog list for that long.)

[C]hoking is actually triggered by a specific mental mistake: thinking too much. The sequence of events typically goes like this: When people get anxious about performing, they naturally become particularly self-conscious; they begin scrutinizing actions that are best performed on autopilot. The expert golfer, for instance, begins contemplating the details of his swing, making sure that the elbows are tucked and his weight is properly shifted. This kind of deliberation can be lethal for a performer.

[An analysis of golfers] has shown that novice putters hit better shots when they consciously reflect on their actions. By concentrating on their golf game, they can avoid beginner’s mistakes.

A little experience, however, changes everything. After golfers have learned how to putt—once they have memorized the necessary movements—analyzing the stroke is a dangerous waste of time. And this is why, when experienced golfers are forced to think about their swing mechanics, they shank the ball. “We bring expert golfers into our lab, and we tell them to pay attention to a particular part of their swing, and they just screw up,” [University of Chicago professor Sian] Beilock says. “When you are at a high level, your skills become somewhat automated. You don’t need to pay attention to every step in what you’re doing.”

Brain research suggests that a major culprit in this problem is loss aversion, "the well-documented psychological phenomenon that losses make us feel bad more than gains make us feel good."

[T]his is why the striatum, that bit of brain focussed on rewards, was going quiet. Instead of being excited by their future riches, the subjects were fretting over their possible failure. What’s more, the scientists demonstrated that the most loss-averse individuals showed the biggest drop-off in performance when the stakes were raised. In other words, the fear of failure was making them more likely to fail. They kept on losing because they hated losses.

There is something poignant about this deconstruction of choking. It suggests that the reason some performers fall apart on the back nine or at the free-throw line is because they care too much. They really want to win, and so they get unravelled by the pressure of the moment. The simple pleasures of the game have vanished; the fear of losing is what remains.

Indeed.

Permalink | Read 4339 times | Comments (1)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Thanks to my NEHGS newsletter, I can point to where my own observations are confirmed (and explained) in print. The Summer 2014 edition of the Old Sturbridge Village Visitor reports on some historical myths, one of which is that everyone died young in the olden days. I get so frustrated when people attempt to explain something in the past by invoking, "because they only lived to be 40 years old." Many of my ancestors lived into their 70's, 80's, and even 90's. Here's the explanation:

While average life expectancy was shorter in 19th-century New England than it is today, many people then lived into old age, and some even lived beyond 100 years. The Bible says that expected lifespan 3,000 years ago was "70 years; 80 for those who are strong" (Psalm 90:10). But before the mid-20th century, people died regularly in all stages of life, not just in old age. Life expectancy at birth in early 19th-century New England was only in the mid-40s.

But as the old saying goes, "there are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics." Statistics in the 19th century were skewed by high childhood mortality rates—especially in urban areas—largely due to infectious diseases such as pertussis, measles, scarlet fever, and diphtheria. (Thanks to vaccination, these diseases are rare today.) By the time a person reached age 30 his life expectancy jumped to 67 and the average 50-year-old could expect to live until age 73.

Note that this still puts many of my ancestors above average, but that's no surprise. :)

My go-to example of what young people can accomplish has always been David Farragut, midshipman in the U.S. Navy at age nine, given charge of a prize ship at 12, later the Navy's first admiral. But the Occasional CEO has provided some other examples for my list:

In 1792, the trading ship Benjamin departed Salem, Massachusetts, loaded with hops, saddlery, window glass, mahogany boards, tobacco and Madeira wine. The ship and crew would be gone for 19 months, traveling to the Cape of Good Hope and Il de France. All the while they bargained hard from port to port, flipping their freight several times “amid embargoes and revolutions,” naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote, “slipping their cables at Capetown after dark in a gale of wind to escape a British frigate; drifting out of Bourbon with ebb tide to elude a French brig-o’-war.” In 1794, the Benjamin returned to Salem with a cargo that brought 500% profit to its owners.

The ship just happened to be captained by Nathaniel Silsbee, 19 years old when he took command. His first mate was 20 and his clerk 18.

I know we expect a different sort of education for our young people today, but surely we can do a better job of helping them get it more efficiently. No wonder today's teens are restive!

The final of the three articles I chose from the January-February issue of Christianity Today is "Who Owns the Pastor's Sermon?" which dives into the thorny issue of intellectual property rights. If a church hires a pastor to preach sermons, do those sermons become church property, or does the preacher retain the copyrights? Right now, the law favors the churches, which is why more pastors are seeking legal help to craft clear agreements. Even though the focus of the article is entirely on pastors and sermons, church musicians, who frequently create intellectual property during the execution of their jobs, should take heed as well.

The law firm of Yates & Yates, which represents many Christian preacher-authors, has a standard agreement, which "recognizes that the pastor, as the creator, owns the intellectual property rights and has the right to determine copyright ownership. ... [T]he pastor grants the church a royalty-free license to use his written or recorded material."

It's the only arrangement that makes sense, said Yates. ... Preachers should own their sermons. If pastors don't own their sermons, that would essentially rob them of their livelihood. ... Pastors wouldn't be able to preach the same sermon in more than one place. And they wouldn't be able to take their sermon notes with them when they moved to a new church, which is "ridiculous," said Yates.

However, the legal situation is more complicated than this.

Frank Sommerville, a Dallas-based attorney who specializes in nonprofit law ... says that under the Copyright Act of 1976, a pastor's sermons qualify as "work for hire." That means the copyrights and intellectual property rights actually belong to their employer.

"It's not the answer that pastors expect," said Sommerville. "They've always taken the position that God gave them the sermon as part of their ministry. It never crossed their minds that there would be a law that would govern their sermons." (More)

Permalink | Read 4199 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]