My random quotation generator greeted me with this when I turned the computer on this morning:

May no gift be too small to give, nor too simple to receive, which is wrapped in thoughtfulness and tied with love. - L. O. Baird

Merry Christmas to all!

Permalink | Read 2014 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

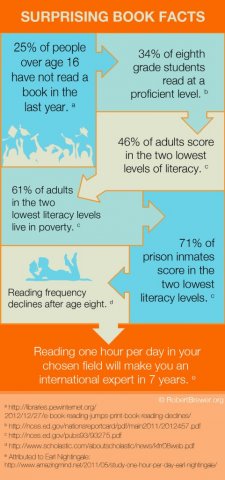

A friend shared this on Facebook. (Click to enlarge; you'll see later why I want to keep it small.)

I'm not criticizing the sharer, nor the original post, because the ideas this image suggests are valid. But I was inspired mostly to comment and to ask questions, beginning with: Where do these facts come from? I'm not going to answer that one yet, because what I found pretty much makes my other comments unnecessary, and I like them, so I'm going to give them first.

- Since approximately two-thirds of high school graduates attend college (and therefore presumably read some books), this implies that the people who don't graduate from high school but later enjoy reading are very rare. Whether or not it's true, it makes sense for the here-and-now, though not in other times and places.

- That forty-two percent of college graduates never touch a book again I find less believable. This is a population that presumably enjoys learning—unless they went to college solely because they bought into the fallacious idea that it would guarantee them high-paying jobs.

- Fifty-seven percent of new books are not read to completion? Hmmm. I suspect that 57% of new books aren't actually worth reading to completion, so I'm not sure this is a bad thing.

- Define "been in a bookstore." I've read 67 books so far this year, but I can't tell you the last time I was in a bookstore. When they closed our local Borders, that pretty much sealed my relationship with Amazon.com. Even before that, the local bookstores almost never had the books I was looking for. Now if they asked me how often I've been in a library in the past five years, that would be an entirely different story.

- Define "buy a book." Does that mean only physical books? If so, it's disingenuous to leave out e-books. Likewise, buying a book is not a particularly lofty goal in my mind (though I've spent a fortune on them); I'm a big fan of libraries. On the other hand, this statistic says that 80% of families did not buy or read a book. So there's another question:

- Define "family." There are about 50 million children in American public elementary and secondary schools, which is more than 15% of the entire population, and a much greater percentage of "families" of even the most generous definition (i.e. including any two or more people living together, with or without children). And it ignores all students in private and home schools, as well as college students. No matter what they do at home, each of these students must have in the last year read not just one but several books (or been read to, for the non-readers). So even stretching the definitions out of all reality, I can't make sense out of the 80% figure.

- And the last one? Reading an hour a day in one field makes you an expert in seven years? I wish! Seven years times 365 days per year is a mere 2,555 hours of reading.

Okay, I've said all that because that's what's currently going around Facebook. But my first attempt at investigation—from squinting at the fine print at the bottom—led me to this page on Robb Brewer's website. There he abjurs "any and all connection" to the statistics in the original graphic, and requests that if people are going to publish it, they use this one instead (again, clicking will enlarge the image):

I didn't check these statistics, because Mr. Brewer clearly did. Except for the last one, which he kept for its feel-good value.

And yes, I had a thousand better things to do than critique a Facebook graphic. OCD takes many forms.

Many thanks to my sister for finding this ray of hope from Oklahoma Wesleyan University after our depressing conversation about the state of higher education, inspired by my Victimizing the Victims post. University preident Dr. Everett Piper's letter has since gone viral, as well it should have, but that won't stop me from adding my voice. The letter is short and well worth reading in its entirety, but I will quote only the final two paragraphs.

Oklahoma Wesleyan is not a “safe place”, but rather, a place to learn: to learn that life isn’t about you, but about others; that the bad feeling you have while listening to a sermon is called guilt; that the way to address it is to repent of everything that’s wrong with you rather than blame others for everything that’s wrong with them. This is a place where you will quickly learn that you need to grow up.

This is not a day care. This is a university.

Would that this kind of sanity would itself go viral.

I enjoy most episodes of the TV show, NCIS, but one I watched recently left me more than usually disturbed. To strip the show of all the redeeming and mitigating features, not to mention the whole rest of the complex episode, what happened was that a man used a hidden camera to videotape a couple of women in an undressed state, and put the videos online. Wrong. Immoral. Creepy. And it's true that one difference between now and BI (Before the Internet) is that such pictures never go away. It's bad. I don't deny it. I don't want to think about how I might react if someone did that to one of our daughters or granddaughters—or grandsons, for that matter.

But still, I think the show is a good example of the overreaction I'm seeing all too often these days. We've gone from ignoring and minimizing the problem of some forms of misbehavior to giving them unwonted significance. As C. S. Lewis once said, in pondering the existence of devils, "There are two equal and opposite errors into which our race can fall about the devils. One is to disbelieve in their existence. The other is to believe, and to feel an excessive and unhealthy interest in them." In the NCIS episode, the event causes one of the women to commit suicide and the other to exult in the murder of the man she believes to have ruined her life forever. And our NCIS heroes reinforce the belief that the cameraman has done irreparable, irredeemable, unforgiveable damage.

What's wrong with this scenario? When people have been violated, when terrible things have happened to them, it's good and right to acknowledge the wrongfulness of the action, to allow them to grieve as much as they need to, and to take action to prevent similar incidents. But are we doing the victims any favors by encouraging them to believe they are ruined forever? That they can never escape what has happened to them? I'm going out on a dangerous limb here, because I've never had an offense that great to recover from—and my track record for forgiving much lesser offenses isn't all that good anyway. But aren't we in danger of perpetuating the crimes, giving eternal power to the victimizers and plunging the victims into helplessness and hopelessness? Condemning them to a life trying to avoid "triggers" the way someone with severe food allergies must live in fear of what that innocent-looking appetizer might have come in contact with?

I think we can do better.

The trigger for this post? Just two days after the NCIS show, I read this Salon article by a former college professor. ("I believed in trigger warnings when I taught a course on sex and film. Then they drove me out of the academy.") WARNING: The article is definitely not grandchild-safe. The author was teaching about "the evolution of the representation of sex throughout American Cinema." You'd think that alone would be warning enough that students would be seeing disturbing images and discussing topics that would make them uncomfortable. I should imagine that anyone signing up for such a class would know what he was getting into. "My classes were about race, gender, and sexuality. These are inherently uncomfortable topics that force students to think critically about their privilege and their place in the hierarchy of this world."

You couldn't pay me enough to take such a course. I have full sympathy with the students who complained about some of the scenes they were expected to watch. What astounds me is the students' (often conflicting) demands to control the content of the class. I didn't take many liberal arts classes in college, so I can't say for sure that it didn't happen then, but I'm almost certain the professors would have responded, "You aren't strong enough to handle my class? Then don't take it." I can only hope this nonsense hasn't infected the physical sciences. (Professor, your statement that 7t x 2 = 14t reminds me of my fourth grade teacher, who used to swat my hand for not knowing the times tables. You need to warn me when you are going to use arithmetic, so I can skip class. And you can't penalize me for not knowing what you taught in my absence.)

A couple of weeks later, graduate students at the University of Kansas demanded that a professor be fired, because they were offended when she uttered the word, "nigger," even in the almost-abjectly humble context that it was hard for her to know how to talk about race relations because, being white, she had not experienced racism herself. "It’s not like I see ‘Nigger’ spray painted on walls…” One complaining student wrote, "I was incredibly shocked that the word was spoken, regardless of the context. ... I turned to the classmate sitting next to me and asked if this was really happening. Before I left the classroom, I was in tears."

She was in tears. She was unbelievably shocked at the mere utterance of a word, in a context of support and attempted understanding. On a college campus where I guarantee other offensive words are flung around frequently, casually, and often with intent to offend. And she is a graduate student, not a second grader. How can one get to the graduate school level and still be so fragile?

Life is hard. For people who have had to deal all their lives with discrimination and racism, with poverty, abuse, illness, handicaps, or other challenges, life is much harder. By what kind of cruel, twisted logic does society encourage someone facing such difficulties to think of herself as weak?

This letter to the Free-Range Kids blog shows a more helpful attitude. (It's probably also not grandchild-safe, depending on the grandchild.) As a child, the man was repeatedly, sexually groped by his barber, and only much later realized what had been going on. In the letter he takes pains not to justify the barber's actions, but neither will he dignify them by assuming they ruined his life. "Try as I may, I cannot summon outrage at the pathetic man who assaulted me. Nor can I conclude that I am any worse for the wear. ... I enjoy a normal life including a healthy-though-unremarkable sex life."

Things happen to us. Good things. Bad things. Sometimes horrible things. They are all part of the material that makes us who we are, and I'm convinced that how we handle them is more important than the events themselves. What can we do to empower those who have been through terrible times to be overcomers rather than perpetual victims?

Permalink | Read 1832 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

My Dear French Brothers and Sisters,

Fourteen years ago we stood where you stand today. While no two experiences, much less cultures, are alike, I will venture to make a prediction: In the midst of the horror you will experience something wonderful: You will be a united country, with opposing factions coming together in their humanity; you will find yourselves giving and receiving unusual kindnesses; and people from all over the world will express their sympathy and support. Strangers will reach out to strangers, as you have done with #portesouvertes. You will be a little more friendly on the Métro, and more patient on the highways. You will stand a little taller, work a little harder, and be a lot more grateful for the people in your lives. You will be yourselves, only better.

Hang onto that.

If you follow in our footsteps, one day you will realize the glimpse of heaven has gone. You will catch yourself cursing the driver who cuts you off. In your impatience you will scream at your kids. Facing someone who disagrees with you, you will once again see a fool or a devil instead of a human being.

Don't let go of the only good gift the terrorists have left behind.

Make no mistake: You are, indeed, at war. War is being made against you, and you have three choices: You can ignore it, you can shrink into isolationism, or you can stand up to your foes. History has shown that the first two options never work for long. The third is costly on many fronts and doesn't always work, either, but it is where hope and honor reside.

How can we stand against such an enemy?

I admire M. Hollande's determination to act with “all the necessary [lawful] means, and on all terrains, inside and outside, in coordination with our allies.” Timidity would only strengthen such a foe, to everyone's loss.

That is what the government can do: the military actions, the large-scale policy decisions, the intelligence gathering and analysis. But what is the role of a citizen? What can everyone do to defeat the terrorists? Here's what I think:

- When we continue to live our ordinary lives and do our ordinary work without giving in to our fears, we are fighting terrorism. Fear is the enemy's most powerful and effective weapon.

- When we refuse to let our anger turn us against the innocent, we are fighting terrorism. Injustice, especially toward the powerless and the hopeless, fertilizes the terrorists' recruiting ground.

- When we make an effort to become friends with those of other nations, cultures, and beliefs, we are fighting terrorism. A faceless, dehumanized enemy is so much easier to kill.

- When we acknowledge, study, appreciate, and build up the good that is unique to our own heritage, while recognizing the same in others, we are fighting terrorism. Our enemies would like to see every culture and belief that is not its own erased from history. If we will not honor and protect our own cultures, history, and ancestors, who will?

- When we resist the hatred that rises within our own selves, we are fighting terrorism. If we become like our enemies, we have handed them the victory.

- When we allow our unbearable pain to be the soil from which grow acts of kindness, attention to the needs of others, expressions of love and appreciation, and attitudes of patience and mercy, we are fighting terrorism. Bringing good out of our sorrow removes a potent instrument of torture from the enemy's hands.

- When we can hold on to both the wisdom of the serpent and the harmlessness of the dove, we can fight terrorism. Keeping the balance puts the battle on our terms, not theirs.

Know that as an American I speak as much to my own country as to yours. We have not set the best example in grappling with our common enemy. Work together with us and all who seek justice, freedom, and peace to find the right path.

Vive la France!

Permalink | Read 1755 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I've known the tune of La Marseillaise for as long as I can remember, along with the first two lines.

Not till two days ago did I pay attention to the rest of the French national anthem. Here's the first, most commonly sung verse (from Wikipedia).

| French lyrics | English translation |

|---|---|

| Allons enfants de la Patrie, | Arise, children of the Fatherland, |

| Le jour de gloire est arrivé! | The day of glory has arrived! |

| Contre nous de la tyrannie, | Against us tyranny's |

| L'étendard sanglant est levé, (bis) | Bloody banner is raised, (repeat) |

| Entendez-vous dans les campagnes | Do you hear, in the countryside, |

| Mugir ces féroces soldats? | The roar of those ferocious soldiers? |

| Ils viennent jusque dans vos bras | They're coming right into your arms |

| Égorger vos fils, vos compagnes! | To cut the throats of your sons, your women! |

| Aux armes, citoyens, | To arms, citizens, |

| Formez vos bataillons, | Form your battalions, |

| Marchons, marchons! | Let's march, let's march! |

| Qu'un sang impur | Let an impure blood |

| Abreuve nos sillons! (bis) | Water our furrows! (repeat) |

I'm sure the French don't usually ponder the meaning of the words any more than we think of war instead of fireworks when we sing about "the rockets' red glare, the bombs bursting in air." But two days ago, ferocious men—I'd rather not dignify a terrorist with the honorable title of soldier—did come right into their arms to cut the throats of their innocent loved ones.

Permalink | Read 2044 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Who prays for Europe? Europe has it all, right? Europe is the motherland of Western Culture, and, in many ways, of the Church. Europe is First World, wealthy, mostly democratic. We once belonged to a church that sponsored a missionary family in France, but as valuable as was the work they were doing, they still had to endure from others not only jokes but also serious questions about why they were wasting time and money in Western Europe instead of some place more needy. Missionaries, humanitarian aid, and prayers should be focussed on Darkest Africa and Remotest Asia, right?

Wrong.

No place, era, or person is beyond the need of fervent, effectual prayer. Hubris thinks that which stands tall cannot be toppled; complacence is blind to enemies without and decay within; envy forgets the lesson of Richard Cory.

Europe is facing a grave economic crisis in the financial insolvency and insupportable policies of Greece (with other countries not far behind). This is no less of a potential catastrophe than it was before it was swept from the headlines by the waves of desperate refugees flooding Europe from their terrorist-ravaged homes-that-are-no-longer-home in the Middle East.

European leaders, the Church in Europe, and all European citizens need the the wisdom of the serpent as well as the harmlessness of the dove. They need open hearts to welcome, comfort, and support those who have lost so much. They need open eyes to discern those who would use the humanitarian crisis as an opportunity to infect European countries with the ideals and weapons of terrorism. They need wisdom to receive a foreign culture without losing their own unique identities.

In short, they need our prayers.

Permalink | Read 2085 times | Comments (2)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Today is the commemoration of the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt. I will set aside any worries over small details like calendar changes, and big details like historical accuracy, because Shakespeare's Henry V is a wonderful play, and his St. Crispin's Day speech one of the most inspiring and uplifting of all time. Kenneth Branagh does it best.

Would you be this cool if you found an eight-foot king cobra under your dryer?

Mike Kennedy's cobra escaped a month ago. Intense efforts on the part of many to find it came up empty.

Last night Cynthia Mullvain was putting clothes in her dryer when she heard a hiss.

Did she panic? Throw a fit? No, but she did call for wildlife officials to come investigate.

They retrieved the missing cobra, which was officially identified by its microchip—not that king cobras are so routinely found in Ocoee, Florida that there was any doubt.

Ms. Mullvain is not suing—someone, anyone, everyone—for pain and distress. She didn't whine to the media about how scared she was, and how no one should have to go through such an experience. She didn't demand that the cobra be killed or not returned to Mr. Kennedy. She's happy to have him go back home, as long as his enclosure is secured.

I think Cynthia Mullvain is one cool lady and reacted just the way a good citizen should have.

Permalink | Read 2192 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Behold, a sower went out to sow. And as he sowed, some seed fell along the path, and the birds came and devoured it. Other seed fell on rocky ground, where it did not have much soil, and immediately it sprang up, since it had no depth of soil. And when the sun rose, it was scorched, and since it had no root, it withered away. Other seed fell among thorns, and the thorns grew up and choked it, and it yielded no grain. And other seeds fell into good soil and produced grain, growing up and increasing and yielding thirtyfold and sixtyfold and a hundredfold.

This parable of Jesus is well-known to Christians, and at least it used to be familiar to the wider world as well. Usually it is given a strictly spiritual interpretation; indeed, Jesus himself appears to endorse that in his explanation. (All quotations are from the book of Mark, English Standard Version.)

The sower sows the word. And these are the ones along the path, where the word is sown: when they hear, Satan immediately comes and takes away the word that is sown in them. And these are the ones sown on rocky ground: the ones who, when they hear the word, immediately receive it with joy. And they have no root in themselves, but endure for a while; then, when tribulation or persecution arises on account of the word, immediately they fall away. And others are the ones sown among thorns. They are those who hear the word, but the cares of the world and the deceitfulness of riches and the desires for other things enter in and choke the word, and it proves unfruitful. But those that were sown on the good soil are the ones who hear the word and accept it and bear fruit, thirtyfold and sixtyfold and a hundredfold.

And yet, as I was reading this chapter the other day, it occurred to me that the parable has a much wider application, which of course doesn't surprise me, as great truths usually apply in many situations. Nor do I claim my thoughts to be original; I'm sure many others have seen the same things. But they were new to me, and I want to write them down.

How often this plays out in my life! Here's one example:

I read a new book or article, hear a lecture or the words of a friend. I might react in any of those four ways. Sometimes an idea may be too foreign, or too objectionable, or I may have strong prejudices against the writer or speaker, and I reject it immediately. For good or for ill, I give it no place in my thoughts. At other times—all too often—I respond to an idea with great enthusiasm, but do not do the work necessary to truly understand it, so when someone—especially someone I care about and/or respect—opposes it, I can't defend the idea, and soon drop it. Frequently the idea makes it through the above obstacles, and I fully intend to apply it in my life, but I get busy with everyday living ("cares of the world"), worry about the cost in money or time ("deceitfulness of riches"), or don't give it priority ("desires for other things") and nothing comes of it. Only if I make an idea my own, give it time and attention, and above all act upon it, will it actually make a difference in my life.

It's also applicable to blogging: I have thousands—tens of thousands—of ideas for blog posts. There's hardly an idea or event that comes my way that doesn't present itself as a possible subject. Li'l Writer Guy (I haven't mentioned him in a while, but he's still around) immediately starts turning it over for possibilities. But many ideas are rejected out of hand as inappropriate; others get dropped when I realize they're not as interesting as I had thought; and most of the rest get dumped into the "blog post ideas" bucket never to see the light of day again, choked out by higher priorities. Only a few of the seeds get the soil preparation and care they need to make it into print.

It's fun for me to see Bible passages in a different light. And maybe useful, too. Recently I've been trying to decipher inscriptions on gravestone photos, and have found photo-editing software to be helpful. Seeing them literally in a different light can sometimes cause what was murky to pop out with clarity.

Permalink | Read 2011 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The Pope is getting all the publicity, but he isn't the only head of state visting a city of historic importance these days. Last week King Felipe VI and Queen Letizia of Spain came to St. Augustine, the oldest city in the United States. St. Augustine is celebrating its 450th anniversary, having been founded by the Spanish on September 8, 1565.

I'll bet the Spanish monarchs, cheered as they were by adoring crowds, didn't make nearly as much of a mess of the city as the visit of Pope Francis is expected to do to Philadelphia.

Permalink | Read 1895 times | Comments (2)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

When I saw this poster at our library I did a double take, and had to record it. We have a friend who trains assistance dogs, and I'd always thought of them as animals that did for people what the people could not do: being eyes for the blind, ears for the deaf, or hands for those with limited use of their own. So how, I wondered, does a dog help those who can't read? Our friend would tell you that her dogs are very clever, but not even she will claim that they can read.

When I saw this poster at our library I did a double take, and had to record it. We have a friend who trains assistance dogs, and I'd always thought of them as animals that did for people what the people could not do: being eyes for the blind, ears for the deaf, or hands for those with limited use of their own. So how, I wondered, does a dog help those who can't read? Our friend would tell you that her dogs are very clever, but not even she will claim that they can read.

Well, it turns out that it's not reading assistance these dogs are giving, but reading education assistance. So I'm guessing that it's our educational system that's handicapped here. There's a video below that explains the program, in which children who are academically or socially impaired get the opportunity to read out loud to specially-trained dogs. As our librarian explained, "The dogs never judge; they just listen." I'll make no judgements about the program itself, which apparently has been quite successful. If it helps kids and doesn't cost a boatload of tax money, go for it. I will, however, vent a little about a society and a system that apparently make such interventions necessary.

How have we managed to make such a hash of learning to read? Children are born smart. Every normal child learns to speak a language (or two, or three, or seventeen) before he ever sets foot in a school. Indeed, he learns the very concept of language. If his parents are Deaf, he learns to sign as well. He learns all this with no formal lessons, no studying, no special programs, no certified teachers, no expensive curricula. Humans are as well-designed for reading as for speaking; how is it that we have made reading so difficult to learn?

Do these children have no parents to read to? No siblings? Are they too busy and impatient? Do they have no pets of their own? Not even a stuffed animal? I'm guessing the sad answer in too many cases is yes.

The "reassurances" near the end of the video sent chills down my spine. These aren't just ordinary pets; all dogs and handlers are "professionally screened, trained, and tested." "Teams wear identifying shirts, bandanas, and badges." The animals are specially treated against allergens before interacting with children. And of course, they are all insured. What kind of a world have we created?

I wonder how much of the benefit the children receive comes from the physical affection given and received with the dog. That's a good thing, but it's tragic that the children are no longer allowed to exchange that affection with their teachers and human volunteers. And each other, for that matter.

Hmm. Maybe we should expand the program. Who wouldn't benefit from a chance to interact with an affectionate, well-trained dog? I'm thinking workplace stress-relief programs. Microsoft and Google, are you listening?

Frankly, he didn't look like the kind of man I'd bother to speak to at a gas station just off I-95 in Virginia. Grizzled, rather the worse for wear, probably living a hardscrabble life—at least judging by appearances. But there was a Confederate flag in his truck's front license plate holder, and it made me smile.

I'm a Northerner by birth and upbringing, and even though I've lived almost half my life in Florida—well, from Central Florida you actually have to travel north to get to the South. So I have my full share of prejudices, and there are days when encountering such a man might have scared me. But today, as we passed together through the convenience store doors, I remarked, "I've never been a fan of the Confederate flag, but I've always been a fan of the underdog, and today your truck made me smile. Thank you." The man gave me a gentle smile of his own, and a kindly (maybe even relieved) twinkle touched his eyes as he responded simply, "thank you."

I may not live in the True South, but multicultural Central Florida has helped me lose at least a little bit of my uneducated and frankly self-righteous and snooty attitude towards its people. And to appreciate that neither side in the Civil War had a monopoly on righteousness, self-sacrifice, and courage; that atrocities are carried out under the flags of many nations and many causes; that thinking you have the right to deride someone for his ancestors only means you haven't looked closely enough at your own; and that attempting to erase history is the mark of a totalitarian state.

The brouhaha that has erupted over Confederate flags and monuments to Confederate soldiers made me realize that our country is not as far from the iconoclasm of Daesh (a.k.a. ISIS) as we'd like to think. It makes me grateful for one man and his truck, refusing to bow to the forces that would obliterate his past. One does not learn from history by forgetting it.

And so, bizarre as it might seem, the Confederate flag brought me a little closer to another human being today, one who I would otherwise have treated as beyond the pale. And so I salute that old Virginian, and sing with Robert Burns,

Then let us pray that come it may, As come it will for a' that, That Sense and Worth, o'er a' the earth Shall bear the gree an' a' that. For a' that, an' a' that, It's comin yet for a' that, That Man to Man the warld o'er Shall brithers be for a' that.

Side note: Immersion in the works of George MacDonald has been of great assistance in understanding and appreciating Burns.

Here's the whole poem, and a translation.

And for your listening and viewing pleasure, the whole song, with pictures of Scotland.

On a radio interview the other day, I heard a woman say an extraordinary thing: I don't believe in sin.

Her statement was received as casually as it was tossed out, but I have been thinking about it ever since. It reminds me of the billboard that used to greet me as I entered the highway near here: God is not angry. That message was sponsored by a church, and I understand where they're coming from. When your parents are mad, do you like to spend time with them, or do you prefer to lie low? My first reaction, however, was that if God isn't angry about some of the things his creatures are doing to each other, he has no business being God.

Oh, if only declaring that we don't believe in sin would make it go away! I wanted to grab the woman by the scruff of the neck and force her to face the victims of child abuse, human trafficking, Mexican drug lords, Joseph Kony, Stalin, ISIS ... and tell me again that she doesn't believe in sin. If there is no sin, would she even be right to feel aggrieved that I had grabbed her by the scruff of the neck?

Permalink | Read 2179 times | Comments (2)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

My airplane dinner was very good, as airplane dinners go, so I don't mean to complain. But I couldn't help noticing that the first ingredient on a wedge of cheese labeled "Swiss cheese" was cheddar. Swiss cheese was there, too, several items later—after water. What's particularly odd is that of all the amazing cheeses readily available here in Switzerland, chedder is not one of them.

And then there was this bottle of Alpine Spring water, "bottled at the source"...

... in Tennessee.

As I sit here, typing away at the edge of the Alps themselves, I can assure you beyond a shadow of a doubt that they are nowhere near Tennessee.

If our laws concerning product labelling allow this, why should I trust any label at all?