I don't know what caused our homeward flight to be delayed five hours. It certainly wasn't the weather, which could hardly have been better for March in New Hampshire. The Southwest Airlines agent said the delay was due to maintenance, but I suspect that any "maintenance" that so disrupts the flight schedule is more along the lines of "repair."

Whatever the cause, at about 2 p.m. we discovered that our 5:30 flight had been rescheduled for 10:30, with the estimated time of arrival in Orlando moved from a very reasonable 8:45 to a very unreasonable 1:45 a.m. Unreasonable, that is, if your ride home from the airport has to get up early to go to work. We looked into alternate flights, but none was direct, and their arrival times into Orlando weren't all that much better. We chose to stay in a situation where if the flight were cancelled the onus was on Southwest to make other arrangements. Porter reserved a rental car instead (there are return places for both Hertz and Avis near our home, which makes this a convenient option), and we settled down to enjoy a little more time with the grandkids.

Not all that much time, as it turned out, because in order to fit our new departure into the Daleys' busy schedule, we had to leave home sooner than strictly necessary. There was a bit of a question just who would drive us there, as Jon had been called out on an ambulance run, but he made it back just in time. The rest of the family stayed home, so there would be plenty of room in the car on the way home for a large load of pellets for the woodstove, but Heather insisted that Jeremiah come, even though he had to be awakened from his nap. I'm sure it was a good decision to let him say goodbye to us at the airport, because at barely two I'm sure he was shocked enough this morning to find us gone.

At the Manchester airport, our flight was famous. They kept one restaurant open well past the normal closing time, so we were able to eat a late dinner while passing the long hours of waiting. The food wasn't great but it was more than we had expected, and we were grateful. Pretty much, if we saw anyone there who wasn't an employee, he was on our flight. Thus after dinner we were able to settle ourselves some way away from the gate (but within eyeshot), and know that we would not be left behind. In fact, the Southwest agent came to us (and the others scattered around) to deliver our two $100 vouchers "for the inconvenience." True, it was inconvenient, but for two adults with no travel deadline it could not be called onerous. (I did keep imagining what it would have been like if we had been travelling with three children under four, as Janet and I had done in the summer.) We settled into a set of comfortable seats with charging stations for two phone and two computers. We were warm and safe; we knew our plane was now in the air and on its way to Manchester; we had work to do and books to read, in peace and relative quiet. Some people might pay a lot for that privilege....

We took off just before 10 o'clock, and all went smoothly with the flight, our subsequent retrieval of luggage, the rental car, and the ride home (none of which should ever be taken for granted). It's times like this when I'm reminded that one of the blessings that came from Porter's years on the road for IBM was a great familiarity with the whole car rental procedure. Even so, this one took some getting used to: it had no keys. Well, it did, but we didn't find them until later, tucked away in a compartment. The only instructions were "depress the brake and press the start button." Figuring out how to turn off the radio was also a trick. Eventually he knew enough about the car to drive it home, but our first computer was less complicated.

We arrived home somewhere in the neighborhood of 2 a.m. Everything was fine except for the clocks, which all insisted it was an hour earlier.

Today Porter is digging his way through Central Florida's surest sign of spring: mountains of fallen leaves, and the trees still shedding. When he is no longer in danger of falling off the screened enclosure into the pool (best-case falling scenario), I will venture out again to replenish the neglected larder.

Our feelings for Southwest Airlines were not of the rosiest when we learned of the long flight delay, but I was impressed by their efforts to make it up to us: not only did the vouchers sweeten the situation, but the cheerful good humor of all the staff was contagious. It's still my favorite airline.

How do you get kids to practice their instruments?

That's the question of all parents who can't help having occasional misgivings about the large outflow of cash going toward music lessons. As far as I can tell, the only honest answer is, "I don't know. It's different from child to child, anyway." Nonetheless, I have made a couple of observations while visiting Heather and family and will set them down for what they're worth.

- Every child here over the age of three takes formal piano lessons. The just-turned-four-year-old is eagerly awaiting informal lessons in the summer, and the start of the "real thing" in the fall. They all enjoy their lessons, partly because their teacher is one of the best-loved in the area, and partly because she's also known to them as Grammy.

- Everyone over the age of six walks or bikes to Grammy's house for his lesson. Not only is this convenient for their parents, but I believe it helps them "take ownership" of the lessons. It also means that if they forget their music books, they're the ones who have to turn around and go back, so responsibility is naturally encouraged.

- Even with these advantages, practice time was hit-or-miss, until a simple change was made. All the kids have morning and afternoon chores, which they are (mostly) in the habit of completing with minimal fuss, "Practice piano" was simply added to the list, and voilà, regular practicing.

- Best of all, the piano is located in the middle of everything. You can hardly go from one place to another without passing the piano. It gets played a lot, because it's there.

- Here's something I'd never have thought of: practicing is a whole lot more fun because the piano is not just a piano. It's a "real piano" rather than just a keyboard, but it is actually an electric keyboard built into a piece of furniture. Thus it comes with all the extras of a keyboard: the ability to record one's playing, multiple timbres, the ability to split the keyboard (have different instruments in the bass and the treble), and more. Yes, this leads to a lot of fooling around, but how many times do you think the kids would practice a particular piece or passage on a mere piano, compared with playing it with the piano sound, then the bagpipes, then organ, then flute, then with various sound effects? Multiple repetitions, painlessly.

I still don't know the secret to getting kids to practice. But I can recognize good tools for a parent's toolbox when I see them.

It's extraordinary how often otherwise civilized people think it's not only their right but their duty to criticize the size of other people's families. I freely confess to doing so myself on occasion, though I do try to limit my comments to general cases, not specific people. Maybe it's because the only remaining area of our sex lives where criticism has not been taken off the table is its fruit (or lack thereof).

Most annoying are the self-righteous critics. You know, the ones who insist that sweet little baby you just gave birth to will destroy the ecological balance of the world. Or those who praise God for the gift of antibiotics and other life-changing interventions while solemnly intoning that your use of birth control betrays your basic lack of trust in God's plan for your family. There are valid points lurking behind both of those extremes, but there is room for such a wide range of disagreement that prudence and courtesy—not to mention the love we owe our fellow human beings, and the good ol' Golden Rule—call us to admit that the size of other people's families is no one's business but their own.

That said, I recently found a Front Porch Republic article that explicates one of the negative side effects of the recent trend toward small families. I highly recommend reading the entire article, but will quote here as much as I think I can without raising the ire of the copyright fairies. (More)

Glenn Doman used to say that what babies and small children want most of all is to grow up, right now. (I've wasted too much time already trying to find the exact quotation, but that's the gist of it.) He must have known Jeremiah.

Jeremiah has two parents and four older siblings, and sees no reason why he shouldn't be able to do everything they can. "Do!" may be his favorite word, meaning "I will do it myself." He has been two years old for all of two weeks, and is busy acquiring new skills at a somewhat alarming rate.

We are staying in the Apartment, which is over the garage and accessible from the kitchen via two doors and a small set of stairs. Before we arrived, Jeremiah could open the door from the kitchen, but not the door to the apartment itself. First thing every morning, we would hear him knocking to be let in. Now he's proud to be able to open the door himself, so we know that when the door opens without an invitation, it's our favorite two-year-old. He hasn't yet learned that there are reasons other than inability for knocking at a door.

We were in the kitchen, and Jeremiah was hungry. I watched as he moved a chair over to the hutch and got himself a plate, then went to the cutlery drawer and picked up a fork. He opened the refrigerator door, selected a container of leftover French fries, which he gave to me. I put some on his plate. Then he opened the door of the microwave, set his plate inside, put a cover on the plate, and closed the door. He waited while I set the time, then pushed Start. (He'd much rather push the other buttons himself, too, but that gets him into trouble.) When the timer dinged, he opened the door, took out the plate, closed the door, took his plate to the table, and proceeded to enjoy his French fries. When I later reported the series of events to Heather, her immediate response was, "Oh, no! He's never been able to open the refrigerator before. Now he'll start getting his own drinks."

Which was true. Not that it's necessarily a bad thing, because he normally does a great job of pouring from a carton to his glass. But sometimes cartons are full and heavy (especially gallon milk jugs) and sometimes they slip. Not to worry (much): he knows what to do. He grabs a napkin or a towel and starts scrubbing away at the spill. But he is (barely) two, and sometimes doesn't remember to set the carton upright before beginning the clean-up process.

Another day I watched while Jeremiah got himself a plate, opened the refrigerator, and took out a package of tomatoes. Then he opened a drawer and took out a cutting board. I intervened enough to ask him to wash the tomato first, which he did. Next he returned to the drawer, extracted his sister's paring knife, and removed it from its sheath. At that point I intervened again (against his will, but he acquiesced with good grace), insisting that I be allowed to guide his hands as he cut, which he did semi-competently. Two years of age is when the kids here begin learning to cut up vegetables, and they become dependable and genuinely helpful well before they turn four. Jeremiah will no doubt learn the fastest of all, because he is so observant and so desperate to grow up, but the arrival of his new brother has delayed his formal lessons, and semi-competent is not good enough when wielding knives. The girls' kitchen knives have been temporarily moved to a less-accessible place.

A tot-lock guards the under-sink chemicals. Again I watched as Jeremiah decided he needed something from that cupboard, took out the step stool, opened it up, climbed to the key's hiding place and took it out. And then ... I was disappointed that I didn't get to find out if he could actually open the lock, because he became distracted by noticing (from his perch on the stool) that the sink was full of soapy water and dishes. He put the key back where it belonged and proceeded to have a different kind of fun.

Oh, and yesterday he casually removed the cap from a childproof bottle, another first.

As his mother says, Jeremiah is a very competent handful.

Permalink | Read 2185 times | Comments (5)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I can see by yesterday's Frazz comic that Frazz lives in Connecticut or some other state that charges a few pennies extra for certain bottles and cans (mostly drink, such as soda and beer—but not water; I have yet to figure it all out), and then gives them back to you if you return the bottle to the grocery store.

What I still don't get about this system is, Why? I mean, I understood it when I was growing up, eons ago, because the bottles were reused. On the very rare occasions when we had beer or soda in the house, we were happy to return the bottles for the nickels they brought (five cents was worth a lot more back then), and so that the companies could refill them. We always put our empty milk bottles back out on the porch for the milkman to retrieve—not for money, but so that he would in turn leave us bottles full of (pasteurized, but not homogenized) milk.

But those days were long ago and far away. No one reuses bottles, and certainly not aluminum cans. I assume that they are all sent from the grocery store to a recycling center. Is a nickel, or even a dime, worth the effort of storing and returning the containers? The real value is in the recycling. The Swiss go through that effort because that's the way recycling is done there—there are no 5-rappen tips for doing what's right. In our town in Florida, we collect all recyclables in one bin which is then picked up at our homes weekly. It's as easy as throwing them in the trash.

The states that I know of that put a deposit on certain recyclables also have home recycling, so wouldn't the marginal cost of picking up all bottles and cans be almost nil? Why, then, do they continue the old practice?

Permalink | Read 2666 times | Comments (11)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

95 by 65 #38 (5 new restaurants, #2) and #48 (visit King Arthur Flour): Two flies with one swat. (This European expression is much more to my liking than our own, as outside of dinner I see little reason to kill birds. I have no such compunctions about flies.)

95 by 65 #38 (5 new restaurants, #2) and #48 (visit King Arthur Flour): Two flies with one swat. (This European expression is much more to my liking than our own, as outside of dinner I see little reason to kill birds. I have no such compunctions about flies.)

Our visit to the King Arthur Flour store, bakery, and café was Part I of our pre-Nathaniel-birth adventuring. (Part II, which contributed to #69, will be the subject of a later post.) KAF's products are good, though not inexpensive, and I loved getting a chance to visit their home turf. Even more, I loved that the employees were so friendly and generous, especially since their generosity came out of their own pockets: KAF is 100% employee-owned.

The food? I had a bite of Noah's sandwich, which was wonderful, but for myself had ordered a simple half-baguette. If you're taste-testing a bakery, you don't want to clutter up the basics with other flavors. My verdict? They do sell great bread in America, even if you'd never know it from the grocery stores and most restaurants. The café is also not inexpensive, so maybe it's a good thing we don't live close enough to eat there on a weekly basis. The temptation would be great.

I also enjoyed browsing the store, though I surprised myself by not buying anything. If I get another chance to visit the store, I'll be more prepared with a plan—and more suitcase room. There's just too much to choose from, especially with five kids anxious to get to the next stop on our adventure. In the meantime, there's always mail-order. And learning to make my own good bread.

I'm still enjoying the Life of Fred math series, as you can see from my booklist; I hope to finish all that the Daleys have before I leave here. Despite what the author claims, it's not really a complete curriculum, but it's a fun supplement, it covers a lot of math, and there's really nothing like it. It covers a lot more than math, too, as five-year-old math professor Fred Gauss makes his way through his busy days. For obvious reasons, the following excerpt from Life of Fred: Jelly Beans caught my eye:

It is not how much you make that counts; it is how much you get to keep. Taxes make a big difference.

In the United States, the top federal income tax is currently 35%. The top state income tax is 11%. The top sales tax is 10%. TOTAL = 56% (56 percent means $56 out of every $100.)

In Denmark, the top income tax is 67%, and the VAT (which is like a sales tax) is 25%. TOTAL = 92%.

If you want to keep a lot of the money you earn, Switzerland's top income tax rate is 13%, and the top VAT is 8%. TOTAL = 23%.

Yes, it's an over-simplification (the book is meant for 4th graders), but it certainly helps distinguish Switzerland from Sweden.

Nathaniel Peter Daley

Born Monday, February 16, 2015, 5:10 a.m.

Weight: 8 pounds, 14 ounces

Length: 21 inches

Heather will eventually have the whole birth story on her blog, and I’ll link to it when she does. But for now, here’s the story from my point of view:

A big storm was predicted for the weekend, so big that Heather and Jon’s church moved their services to Saturday. Long-time New Hampshire residents thought that was rather wimpy of them, and that the news media was doing what they do best: making mountains out of molehills. Nonetheless, when Heather had some signs of early labor during the church service, we began keeping more of a “weather eye” out than usual.

By the early hours of Sunday morning, contractions were 15 minutes apart. We wouldn’t normally leave for the birth center at that point, but a great deal of snow had fallen and was still falling at a great rate. Jon dug out the car, then did it again after the snow plow came through, then once more after we were all ready to leave.

Porter, Jeremiah, and Faith stayed at home this time. Jeremiah is in a stage where he’s very independent most times, but when he wants Mommy, he really wants only Mommy if Mommy is anywhere nearby. He’s also very sensitive and easily upset when he thinks Mommy is hurt or unhappy, so the plan was to let him stay with Dad-o. Faith then decided that she didn’t care about being at the birth; all she wanted was to hold the baby when he came home. This turned out to be very convenient, as with the baby we would have exactly the maximum number of people who could fit in the car.

Jon is an excellent winter driver, and he needed to be. The roads weren’t too bad at first, but after we left town the plows were clearly behind schedule. We were very thankful for rumble strips on both the sides and middle of the road; otherwise we could very easily have been on the wrong side of the two-lane highway. We made it to the birth center without incident; it had not been plowed, but we were able to follow in the tracks the midwife's car had made.

We settled in, anticipating a bit of a wait, but not a long one.

The baby had other ideas.

Contractions, which had been strong in the car, slowly petered out, and after many hours of waiting, everyone was ready to go back home. The midwife told us that it is not uncommon for storms to provoke labor that then subsides. So we bundled back into the car, and returned home on roads that were better than they had been. Porter and our friend Don (who had come for a brief visit and some games, but got more than he'd bargained for) had shovelled the driveway so we could get back in.

The midwife was right: the rest of the day was quite normal. It wasn't until—of course—the wee hours of the morning that labor began again in earnest. And the baby wasn't kidding this time. Contractions came fast and furious in the car, and Jon made the 40-minute return trip to the birth center in record time. He's driven the ambulance so many times on those roads that he knows exactly where he must go slowly and where he can gain time. The roads and visibility were much better than the day before, which was a good thing, because a car birth would have been not only uncomfortable, but also downright dangerous in the sub-zero temperatures and high wind. It was SO COLD.

Although we all anticipated a birth soon after arrival, once again the baby had his own plans. But at 5:10 a.m., after a gentle water birth, he rose to the surface and announced his presence with a hearty voice. Joy had been given the job of determining and announcing whether they had a new sister or a new brother: "It's a boy!"

After a short rest and recovery period, we once again headed for home, where Porter, Faith, and Jeremiah waited to welcome the new baby. True to her word, Faith has held him at every possible moment, probably more than anyone other than Heather. It took a record 48 hours to name him (Noah held the previous record), but with or without name he's been patiently stepping through the newborn routine of eat-sleep-eliminate, repeat. Mom, baby, and the whole family are doing well, and everyone loves the newest little Daley.

Welcome to our world, and to your very loving family, Nathaniel!

Permalink | Read 3245 times | Comments (5)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Far be it from me to minimize the intelligence and contributions of Henry Louis Gates, Jr. My own feelings about him are mixed, as I think he acted irresponsibly and reprehensibly in the Cambridge Incident. Not his initial reaction—I wouldn't want to place any bets on my own rational behavior after returning from an exhausting overseas trip and finding myself locked out of my house, then being suspected by the police of housebreaking. But for escalating the affair even after the facts were known. At least I think that I, upon calmer reflection (and perhaps some much-needed sleep), would have been grateful to have had a neighbor notice that someone was jimmying my door, and police willing to be certain the housebreaker was who he said he was.

That aside, however, I can't deny his accomplishments, nor fail to appreciate his contributions to the genealogical field, especially in making it more popular and accessible to many who otherwise would never have given it a second thought. For a while we watched his PBS series, Finding Your Roots, though just as with Who Do You Think You Are? and Genealogy Road Show, it got tiresome after a while: too much hype, too many celebrities, not enough content. His work is serious, and his passion genuine.

Recently Gates was interviewed in the American Ancestors magazine published by the New England Historic Genealogical Society. His passion shows in his answer to the question, Where do you see genealogy in five or ten years? What do you think is going to happen?

I'm working with a team of geneticists and historians to create a curriculum for middle school and high school kids, to revolutionize how we teach American history and how we teach science using ancestry tracing. Every child in school would do a family tree. We think that's the best way—to have their DNA analyzed and learn how that process works in science class. In American history class, we think that's the best way to personalize American history and the nature of scholarly research. For a lot of kids, going to the archives, looking at the census is boring. But if we say, "You're going to learn about yourself, where you come from," what child wouldn't be interested in that?

Really? Really? I'm 100% with him on the idea that genealogy makes history personal and for me far more interesting. I can feel and appreciate his enthusiasm. But can you imagine parental reaction to this particular permission slip? This is several orders of magnitude greater than the privacy violations already imposed on families by the schools. Genetic genealogy is a very young science with innumerable risks and ethical pitfalls. Even those of us who value the genetic information available aren't necessarily thrilled with the idea of our genetic information being "out there."

Medical fears Who else can learn that I have a genetic predisposition to cancer, or bipolar disorder? If I get tested, will I be morally obligated to reveal the results to my family, my doctors, or on an insurance or employment application? Do I even want to know myself? If the school learns such a thing about my child, will that affect their treatment of him? Could they initiate a child abuse claim if we refuse to take whatever steps they recommend based on this knowledge?

Sociological and psychological fears A child discovering that his father isn't the man he has called Daddy all his life. A youthful indiscretion revealed by the discovery of an unexpected half-sibling. Decades-old adulteries brought to light. We like to hear of the DNA-testing success stories, of Holocaust survivors reunited with family members they thought long dead. But there's a darker side to the revelations: as one man wrote, With genetic testing, I gave my parents the gift of divorce. Even if we're certain there are no skeletons in our own closets, or don't care if they're brought to light, can we be so sure about other family members? Can we speak for their wishes? What's revealed about our DNA affects other lives; no man is a genealogical island.

Security fears I have too much respect for hackers and too many misgivings about the NSA to believe any reassurance that the data is secure. And indeed, much of the information desired by those who have their DNA analyzed is only useful if it is shared.

To be sure, there's a lot of very interesting data that can potentially be mined from DNA testing, and I'm not saying I'll never consent. It's tempting, to be sure. But it's not a decision to be entered into lightly, and certainly not one to be imposed on a family by a middle school history teacher. Even one as enthusiastic and as persuasive as Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Mother Goose & Grimm isn't one of my favorite comics, but every once in a while they do something I really like. Maybe this is only impressive to a select few, but my nephew is one of them, so....

Permalink | Read 2289 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

#37 Share at least 20 meals with others: We met my brother for dinner at ...

#38 Try at least 5 new restaurants: ... the Nile Ethiopian Restaurant, after having enjoyed ...

#24 Attend 15 live performances: ... this year's Horns & Pipes concert. And came home to ...

#49 Keep up a 10 posts/month blogging schedule for 20 months ... write about it!

A great day, but exhausting for an introvert, so at the moment it's about 50/50 whether I'll get some much-needed work done, or just go to bed and hope for an early start in the morning.

And they wonder why some people take doctors' recommendations with a grain of salt. The same medical establishment that pushes the Back to Sleep campaign and is now spreading panic over measles (though I mostly blame the media for that) has declared our grandchildren to be out of compliance.

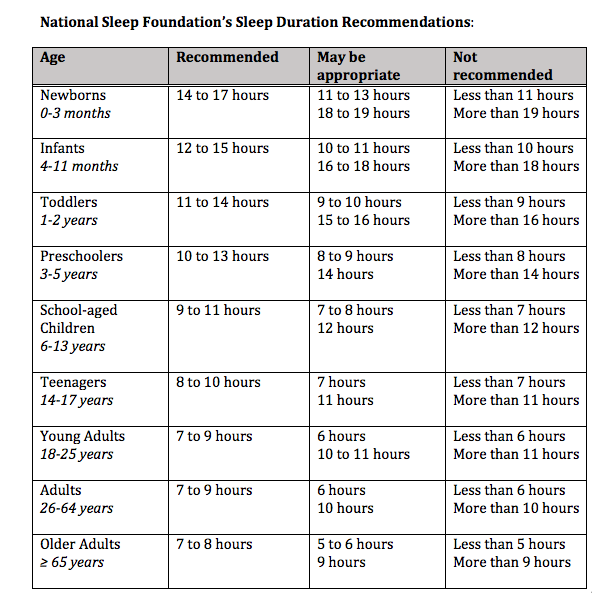

The National Sleep Foundation and the panel of experts has come up with new sleep recommendations for various age groups. To wit:

I'm all for sleep, and agree that most people don't get enough, myself included. But did you catch the recommendations for babies? Newborn to three months, 14-17 hours? Four to eleven months, 12-15 hours? Porter wonders if the doctors are recommending drugs or the ol' baseball bat trick to enforce those limits. I'm pretty sure none of our eight-and-counting grandchildren slept that much in a day. It's possible our own children did, but I was too sleep-deprived at the time to have established reliable memories.

I thought it would be easy. I have no small children at home. I have no paid employment. Life at the moment is, generally, calm. Surely it wouldn't be hard to pretend I had a half-time job, and dedicate 40 hours over two weeks to genealogy work. However, this task turned out to be surprisingly difficult. It took 18 days, not 10, to log the 40 hours, and before it was over I found myself heartily sick of genealogy. It was an instructive exercise, however. A few observations:

- I can make a surprising amount of progress if I hole myself up in my office, ignoring phone calls, e-mails, Facebook, and even to some extent my husband.

- Ignoring other responsibilities in order to meet my genealogy goals (or any other specific goals, I suspect) eventually builds up so much psychological pressure (guilt) that the once-pleasurable work becomes a chore.

- Phone calls from grandchildren cannot be ignored.

- My goal was to work in concentrated segments of at least an hour each, but I found that surprisingly hard to manage, and eventually allowed myself sometimes to count the accumulation of smaller time periods. Otherwise, it was too frustrating to find myself with, say, a half an hour to work and yet know I couldn't count it towards the goal.

- The original impetus for this exercise was the expiration of my Ancestry.com subscription. Deciding to renew it took a bit of the wind out of my sails and slowed my progress, but I did eventually pull myself together and finish only one day later than my end-of-January goal.

- I had hoped the push would make a good dent in my accumulated backlog of genealogy work. Ha! Infinity minus anything is still infinity. Still, it really did help, and I made some good finds, though in trying to "beat the expiration clock" I spread my work very thinly, and concentrated more on new data than on entering the old, so the backlog looks more worse than better.

- Having a full year's subscription ahead of me, however, and a plan to put in a steady hour or two each week, I'm hoping some more methodical plodding will bear good fruit.

Another goal, albeit one of the easier ones, accomplished: I reaearched and bought a food processor.

Actually, I have one already, and hardly use it. So why buy a new one?

The one I have was a gift from my father, many, many years ago. I have a hard time getting rid of something associated with someone I love. Or some place I love. Or any situation with positive memories. Even if it's broken or no longer useful. Okay, I'll admit it: I have a hard time getting rid of things. I'm working on that.

This appliance was a combination blender and food processor, and the blender part gave up and was replaced years ago. I hadn't used the food processor part very much, but it still worked, so of course I kept it. I used it almost exclusively for making cole slaw, but eventually it became easier (and faster) to shred the cabbage by hand—and even easier to buy pre-shredded cabbage at the grocery store.

Not long ago, I found a recipe that I wanted to try, and it recommended using a food processor to shred the cauliflower, so I dug ours out. And discovered why I rarely use it. The motor wasn't powerful enough, and the workings kept getting jammed, so I'd have to stop, clear it out, and restart, over and over again. The process finally completed, but it was a pain, and made mess. However, it turned out that we both like the recipe, so I want to make it again—only without so much hassle.

After some thought, I concluded that I'd use a food processor for much more than shredding cauliflower—if it worked as I think it should. I'm generally loath to bring more potential clutter into the house, but I wanted to give the idea of the appliance a second chance. Hence #29 on my list.

I decided on the Cuisinart DLC-10S, attempting to hit the midpoint between unnecessarily complex and expensive, and too cheap to do the job. Time will tell. After I get a chance to play with it some, I'll come back and comment here.

For the curious, here's the recipe that drove this decision. Follow the link for the original; the text version below reflects my small modifications and notations. Also note: This is a "Paleo" recipe, and I emphatically don't do Paleo. But I'm not a vegetarian either, and some vegetarian recipes are really good. Also, I don't care what the title says, these are in no way anything deserving of the name "biscuits." You don't have to be a Southerner to appreciate that! However, even though our Maryland friends would throw their own hands up in horror at the thought, we both found them a quite acceptable "crab cake," especially with cocktail sauce. Delicious, in fact, and I suspect they could be made vegetarian without much loss by leaving out the bacon. Who'd have thought cauliflower could taste so good? Then again, who'd ever have thought of putting cocktail sauce on cauliflower?

Cauliflower Biscuits with Bacon & Jalapeño

Ingredients

- florets from one head cauliflower (Next time I'll include more of the stems, since you shred them anyway.)

- 2 Tbsp extra virgin olive oil

- 1/2 cup almond flour

- 2 eggs

- 1/3 cup fully cooked bacon, chopped

- 1/2 tsp garlic powder

- 1/2 tsp salt

- 1/2 tsp black pepper

- 1 jalapeño, chopped

Directions

- Preheat the oven to 400ºF.

- Using a food processor with a shredding blade attachment, shred the cauliflower.

- Heat the olive oil in a large skillet over medium heat.

- Sauté the shredded cauliflower with jalapeño, bacon, & spices for about 7 minutes to get the cauliflower cooking (should be softened & slightly translucent). (I found it took much longer than 7 minutes.)

- Remove from heat, and stir in the eggs & almond flour.

- With a 1/4 cup measuring cup, scoop the mixture onto a baking sheet lined with parchment paper.

- Bake the biscuits at 400ºF for 35-40 minutes, or until they look browned & crispy. (For my oven, this was too long. They were still good, but would have been better not so brown on the bottom.)

- Allow the biscuits to cool on the sheet for about 5 minutes before transferring to a cooling rack.

Gifted Hands: The Ben Carson Story. This movie needs no more review than this: See it.

But of course I can't leave it at that. There are so many films, shows, books, and even Great Courses lectures I'd love for my grandchildren, especially the older ones, to experience, but there's always something that turns a great story into something NSFG. We used to be able to portray the rawer side of life in a way that left something to the imagination, but that sensitivity is now out of style. Gifted Hands, despite being non-rated, is a happy exception. There are some difficult situations and heartbreak, but nothing to detract from the story.

Ben Carson from inner-city Detroit, raised by a single mom (but what a mother!), failing in school, headed for trouble. Dr. Ben Carson, world-famous director of neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins. Gifted Hands tells the tale—fictionalized and condensed, but remarkably accurate for all that—of the transformation. The movie is enjoyable on many levels, from watching Ben's mother inspire her children to learn, to getting a glimpse of the Biltmore House library (professor's house in the movie), to realizing that it's possible to be both a top-notch neurosurgeon and a humble and good-natured person.

Great story. No caveats. Much inspiration. Enjoy!