Another goal, albeit one of the easier ones, accomplished: I reaearched and bought a food processor.

Actually, I have one already, and hardly use it. So why buy a new one?

The one I have was a gift from my father, many, many years ago. I have a hard time getting rid of something associated with someone I love. Or some place I love. Or any situation with positive memories. Even if it's broken or no longer useful. Okay, I'll admit it: I have a hard time getting rid of things. I'm working on that.

This appliance was a combination blender and food processor, and the blender part gave up and was replaced years ago. I hadn't used the food processor part very much, but it still worked, so of course I kept it. I used it almost exclusively for making cole slaw, but eventually it became easier (and faster) to shred the cabbage by hand—and even easier to buy pre-shredded cabbage at the grocery store.

Not long ago, I found a recipe that I wanted to try, and it recommended using a food processor to shred the cauliflower, so I dug ours out. And discovered why I rarely use it. The motor wasn't powerful enough, and the workings kept getting jammed, so I'd have to stop, clear it out, and restart, over and over again. The process finally completed, but it was a pain, and made mess. However, it turned out that we both like the recipe, so I want to make it again—only without so much hassle.

After some thought, I concluded that I'd use a food processor for much more than shredding cauliflower—if it worked as I think it should. I'm generally loath to bring more potential clutter into the house, but I wanted to give the idea of the appliance a second chance. Hence #29 on my list.

I decided on the Cuisinart DLC-10S, attempting to hit the midpoint between unnecessarily complex and expensive, and too cheap to do the job. Time will tell. After I get a chance to play with it some, I'll come back and comment here.

For the curious, here's the recipe that drove this decision. Follow the link for the original; the text version below reflects my small modifications and notations. Also note: This is a "Paleo" recipe, and I emphatically don't do Paleo. But I'm not a vegetarian either, and some vegetarian recipes are really good. Also, I don't care what the title says, these are in no way anything deserving of the name "biscuits." You don't have to be a Southerner to appreciate that! However, even though our Maryland friends would throw their own hands up in horror at the thought, we both found them a quite acceptable "crab cake," especially with cocktail sauce. Delicious, in fact, and I suspect they could be made vegetarian without much loss by leaving out the bacon. Who'd have thought cauliflower could taste so good? Then again, who'd ever have thought of putting cocktail sauce on cauliflower?

Cauliflower Biscuits with Bacon & Jalapeño

Ingredients

- florets from one head cauliflower (Next time I'll include more of the stems, since you shred them anyway.)

- 2 Tbsp extra virgin olive oil

- 1/2 cup almond flour

- 2 eggs

- 1/3 cup fully cooked bacon, chopped

- 1/2 tsp garlic powder

- 1/2 tsp salt

- 1/2 tsp black pepper

- 1 jalapeño, chopped

Directions

- Preheat the oven to 400ºF.

- Using a food processor with a shredding blade attachment, shred the cauliflower.

- Heat the olive oil in a large skillet over medium heat.

- Sauté the shredded cauliflower with jalapeño, bacon, & spices for about 7 minutes to get the cauliflower cooking (should be softened & slightly translucent). (I found it took much longer than 7 minutes.)

- Remove from heat, and stir in the eggs & almond flour.

- With a 1/4 cup measuring cup, scoop the mixture onto a baking sheet lined with parchment paper.

- Bake the biscuits at 400ºF for 35-40 minutes, or until they look browned & crispy. (For my oven, this was too long. They were still good, but would have been better not so brown on the bottom.)

- Allow the biscuits to cool on the sheet for about 5 minutes before transferring to a cooling rack.

Gifted Hands: The Ben Carson Story. This movie needs no more review than this: See it.

But of course I can't leave it at that. There are so many films, shows, books, and even Great Courses lectures I'd love for my grandchildren, especially the older ones, to experience, but there's always something that turns a great story into something NSFG. We used to be able to portray the rawer side of life in a way that left something to the imagination, but that sensitivity is now out of style. Gifted Hands, despite being non-rated, is a happy exception. There are some difficult situations and heartbreak, but nothing to detract from the story.

Ben Carson from inner-city Detroit, raised by a single mom (but what a mother!), failing in school, headed for trouble. Dr. Ben Carson, world-famous director of neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins. Gifted Hands tells the tale—fictionalized and condensed, but remarkably accurate for all that—of the transformation. The movie is enjoyable on many levels, from watching Ben's mother inspire her children to learn, to getting a glimpse of the Biltmore House library (professor's house in the movie), to realizing that it's possible to be both a top-notch neurosurgeon and a humble and good-natured person.

Great story. No caveats. Much inspiration. Enjoy!

This is me, eating crow.

I've always had problems with the AARP. I don't like their politics, and I resent the frequent junk-mail reminders that I'm getting older and should sign up. When Porter joined—chiefly to get the AARP discount at Outback Steakhouse—I reluctantly put the card in my wallet, but was ashamed of its presence. Having campaigned for decades against age discrimination, I still don't like the idea of an old-folks organization, and have thus far refused to read their magazine or even check out their website, though Porter says they have some interesting games. It's a matter of priniciple.

As it turns out, some principles go only so far, and mine broke down today. I discovered the AARP discount at Ancestry.com.

Remember my 95 by 65 goal to put in 40 hours of genealogy work by the end of January? The chief impetus for that was the upcoming end of my Ancestry.com subscription, which I had planned to let expire for a while. However, at least until March 4 (after which the agreement may or may not be renewed), AARP members receive a 30% discount on the World Explorer membership. Thirty percent!

Pricing at Ancestry is so complex that I made a spreadsheet just to figure it all out. (Or maybe that's just me.) Not only are there different extents of Ancestry membership (World, or U.S. only), and different time periods (monthly, semi-annually, annually) but their World Explorer Plus membership also provides annual subscriptions to Fold3 and Newspapers.com. The Ancestry website is not nearly as forthcoming with prices as it could be, making comparisons difficult.

Enter the world of the phone and the human interface. I'm not a phone person, but this was worth it. I learned the truth of what was so confusing on the website: The World Explorer Plus membership cannot be given as a gift, and the AARP discount only applies to World Explorer, not U.S., and most importantly in my case, not with the AARP discount. The last was a disappointing loss, but it turns out that Fold3 and Newspapers.com offer a 50% discount to Ancestry.com members, which adds up to only $8 more than if the AARP discount had applied to the World Explorer Plus membership. (Are you confused now? That's why I made the spreadsheet.)

Plus, because I upgraded my membership before it actually expired, they added an extra month to my subscription. That's never happened before, but I was happy to take it. When this membership is about to expire, I'll be sure to call ahead of time to see if the AARP discount is still active, or if there's something else useful. I'd never have known if I'd just let my subscription expire, or renewed online.

I still have problems with the AARP. But I'll take the perk. In this transaction alone, the $16 membership fee saved me $90.

What, pray tell, is the point of being able to get a foreign product in the U.S. if it has the same or similar name but has an entirely different composition? I made this discovery earlier, when Nestlé acquired the rights to market the Ovaltine malted chocolate drink in the United States. I remember Ovaltine as a child, the name having been changed from the Swiss Ovomaltine by a typo in the legal papers. In Switzerland, Ovomaltine comes in many forms, from awesome chocolate bars to cookies to breakfast cereal to the hot chocolate drink that Nestlé appears to be imitating. But there turns out to be a huge difference between the two products: the version you can buy in America has been modified beyond recognition, to conform more to other Nestlé product flavors. Most importantly, what is overseas an entirely malt-sweetened product is in America loaded with sugar. I'm a big fan of sugar, to be sure, and other Ovomaltine products in Switzerland do make use of that ingredient. But when you have a perfectly good chocolate product without added sugar, why mess with it?

Ask the people at Hershey. Being from Pennsylvania, I have a natural sympathy with the Hershey company, even if I find their chocolate mediocre. But this time they've gone too far. I'd wondered why Cadbury chocolate no longer tasted as good as I remembered it from a long-ago visit to England, but had just assumed that memory was gilding the previous exprience. No, I was informed by my brother, who lived in England for quite a while and visted yet more recently. In America, he said, chocolate under the Cadbury name is an entirely different product from that in the U.K. And while one used to be able to purchase the real thing in some specialty shops, Hershey has broght that to an end through (surprise, surprise) a lawsuit.

Hershey's has blocked British-made Cadbury chocolate from entering the US. The chocolate company struck up a deal with Let's Buy British Imports to stop imports of Cadbury products made overseas ... A Hershey's representative told The New York Times that the company has the rights to manufacture Cadbury chocolate in America using different recipes, and that importing British chocolate is an infringement.

Once again: same name, different product for dumb Americans.

The New York Times broke down the major differences between the kinds of chocolates. "Chocolate in Britain has a higher fat content; the first ingredient listed on a British Cadbury’s Dairy Milk (plain milk chocolate) is milk" ... "In an American-made Cadbury’s bar, the first ingredient is sugar." The American version also contains preservatives.

This deception is now protected by copyright law.

As promised in my Leon Project post, here is my list of 95 things to accomplish by my 65th birthday, which is approximately two and a half years away. The list was extraordinarily difficult to create. Others have told me they had trouble coming up with such a large list; for me the problem was to keep it from expanding exponentially. I am terribly intimidated by both the apparent ambitiousness of the list—which includes many projects that have languished on my To Do list for years, even decades—and by knowing that I've left out far more of what I want to do than I've included, not to mention the activities that make up most of everyday life. Many of the items on the list can be broken down into 95 items of their own. A few are simple; I put those in to keep myself encouraged, though unfortunately I had to take many of them out to pare the list to 95. When I think of the time and effort this list represents, and realize that it's but a sampling of what I want to accomplish, it's no wonder that "my work" fills my days and is never far from my thoughts. But, to claim a cliché from our old favorite General Electric ride at EPCOT (Horizons), If we can dream it, we can do it. At least I'm going to try. Certainly it's a lot more likely to happen than if I don't dare to dream it.

I spent a ridiculous amount of time trying to categorize my list items. In the end, I shamelessly copied from Stephen Covey's To Live, To Learn, To Love, and To Leave a Legacy. Live gets the items related to everyday life and to health, including organization and exercise. Into the Love category I put spiritual exercises, anything for which I deem the primary purpose to be social (from watching movies to visiting friends to joining Twitter). Learn gets reading and other cultural activities, mental exercises, and language learning. My genealogy work goes into the Legacy category, along with Grandma's Treasure Chest and other educational materials creation, and photo/audio/video work. Some items could easily go into more than one category, but I made myself stop stressing about that: this is a tool, not a master, and it doesn't need to be perfect. It just needs to be.

I look forward to collaborating with Sarah in mutual support and encouragement. And to having a list of accomplishments as a 65th birthday present for my inner Leon.

Here's is the original list. If anyone wants to follow my progress, there's a link to the Google Sheet on the sidebar (under Links/Personal). (More)

Permalink | Read 3186 times | Comments (7)

Category The Leon Project: [first] [newest] 95 by 65: [first] [next] [newest]

Are Grossmutti and Grossvater ready for guests from Florida? Who knew there was a secret passage from Diagon Alley, Orlando to Basel-Land?

Permalink | Read 2158 times | Comments (2)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

It takes a rich, greedy capitalist to grind the poor into the dust, right? Certainly over the years many have done a very good job of that. Our recent viewing of the documentary, Queen Victoria's Empire, drove home the disastrous consequences of both imperialism in Africa and the Industrial Revolution back home in Britain.

However, the same video also revealed the devastation that can be wrought by someone with good intentions, even against his will (e.g. David Livingstone), and especially when combined with the above-mentioned greed (e.g. Cecil Rhodes).

Which brings me to the point. I cannot count the hours and hours of struggle Porter has put into getting us health insurance in these post-retirement times. Without a doubt, I am personally grateful for the choices the Affordable Care Act (a.k.a. Obamacare) offers us, as much as I philosophically fear its negative consequences. Some of those negative consequences are personal, too: e.g. the colonoscopies that had been covered by our insurance in the past no longer qualify for coverage because of new rules instituted by the ACA. And we can't afford to get sick until after the end of January, because the "helpful" phone contact assigned us the wrong Primary Care Provider, and the fix won't go into effect till February 1. However, I admit to no longer hoping for repeal of the ACA, because the damage has been done. Too many people, including us, are now dependent on it. I doubt we can put the genie back in the bottle.

While I freely acknowledge that the passage of the ACA had at its heart noble ideals and good intentions, I'm not convinced it's really helping the poor, or at least not as much as it's helping people who get rich off the needs of the poor. Porter, being retired, has the time to put into navigating the complex and exceedingly frustrating waters. He also has a degree in economics and a mind well-suited to financial calculations. Which convinces me that the truly impoverished will (1) throw up their hands and settle for a much less than optimal health care plan, or (2) fall prey to those who would profit from doing the paperwork for them, while charging inordinate fees and still coming up with a less than optimal plan.

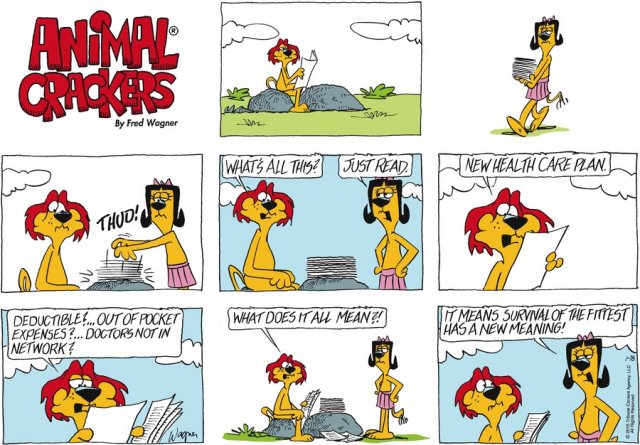

Nonetheless, the purpose of this post is neither to start a political discussion nor to depress you. It's to honor my husband, for whom Sunday's Animal Crackers comic could have been created:

No doubt about it: I married the right man.

Permalink | Read 3167 times | Comments (0)

Category Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Leon? Who or what is Leon?

Leon was my boss a few eons ago, back at the University of Rochester Medical Center. He was a good boss, but one thing about him frustrated me. Day after day I'd work steadily, creating algorithms and developing computer programs for our laboratory. To all appearances, this did not impress him; it was simply what he was paying me to do. What made him light up with pleasure and praise, however, was when I'd take the extra time to create a computer display related to my work. Although I learned to produce these displays periodically, mostly to please him, it drove me crazy that I was being recognized for the "flash," and not for the bulk of the work, the more important work, that was behind it. However much he might have trusted me to do good work (he chose to hire me, after all), he also needed the occasional, tangible reminder that I was worthy of his trust. As it turned out, so did I.

Fast forward to every homemaker's frustration, every mother's least favorite question: What do you do all day? We know how long and how hard we work, and how critically important our labors are. All too often, however, the people we meet at parties, our friends in paid employment, and even those closest to us seem sincerely puzzled as to why our jobs take up so much time. That is frustrating to no end, but in fact it's true of most professions. No one from the outside can truly appreciate what it takes to do another's job, particularly since the hallmark of the best in a profession is the ability to make the work look easy.

I've discovered over time that Leon was not alone in his need for tangible measures of the value of our work. Maybe there's no purpose in sharing the details with people we meet at parties, but bosses, co-workers, spouses, fellow-strugglers, and even (no, especially) we ourselves need occasional reassurance that we are making progress. We are all Leon.

Why, then, do some of us find it so difficult to provide measurable documentation of our work? I've come up with a few suggestions, based on my own experience and on what I've learned from others.

- It takes time away from more important work. Who needs to add yet another camel-straw to the crushing burden of work undone versus sand slipping through the hourglass? As I learned in the computer biz, however, documentation is essential, however much it feels like a waste of precious time. Without documentation, others can't step in when we have to step back. What's more, putting what we do into words brings clarity to our own vision. If we don't know something well enough to explain it, we don't know it well enough.

- We don't like to make our work public until it's in final form. This is perfectionism, and Don Aslett would not approve. In fact, he insists that telling others about our work while it's still in progress is a good way to get help. It's also a good way to get kibitzers and critics, however.

- Our goals have long paths and far horizons. How do you quantify a happy child? A valued relationship? Growth and development? How can we help people appreciate our work without making their eyes glaze over? A journalist can point on a regular basis to articles published, a doctor to patients cured, and a trash collector to clean streets, but in many professions success, when it comes, is preceded by thousands of failed experiments, research lines that didn't pan out, apparently fruitless counseling sessions, and draft pages ripped from typewriters, crumpled and tossed away. It's all part of the process, but not conducive to marking milestones and erecting ebenezers ("hither by Thy help I'm come"). The employed can at least point to a paycheck, but unpaid work lacks even that.

- We're not "announcers" by nature. Some people like to chat about all the details of their lives, no matter how intimate or trivial. These are good people to have around, as they take the greater share of the conversation burden. But some of us don't see the point of such loquaciousness, or are simply uncomfortable with the idea. This is another good reason for developing a documentation strategy: we take control over what and how we share.

- We want to be trusted with our own work. We are not employees, and don't like the feeling that we are being supervised. As it turns out, however, this is not as significant a factor as I had once thought. We're not employees? Well, the self-employed have the hardest taskmaster of all, one who knows best all our weaknesses, struggles and failures. That boss needs the comfort of tangible markers more than anyone.

In light of these meditations, I've developed The Leon Project. Call it a New Year's resolution if you wish. I have hundreds of ongoing projects in various stages of completion, including not-yet-started and not-in-this-lifetime (genealogy is never finished!). This year I'm making an effort to document where I am, what I'm doing, and where I want to go, with hopes of developing a better road map, complete with milestones to which I can look back and say, "thus far have I come."

A large part of this effort will involve partnering with my sister-in-law in her "101 Things in 1001 Days" project. I have approximately two and a half years until my 65th birthday, which falls a bit short of 1001 days, so I'm calling my version, "95 by 65." (That will become a link when I publish its own post.) She started her project last year, but has graciously adjusted her schedule so that we both will finish on my 65th birthday. We are hoping that by doing our projects together we can encourage each other to keep going and reach our goals—which range from the trivial to the highly ambitious.

I've created two new post categories, The Leon Project and 95 by 65, in expectation of keeping some of the anticipated documentation here. I look forward to the adventure with both enthusiasm and trepidation.

Aside: This is not the first Leon Project post I have written. A few days ago the first one was nearly ready to post, but somehow overnight the bulk of the long essay disappeared. (Note to self: never assume that something you thought you saved actually succeeded in that process.) It took a while before I got to the point of being able to rewrite, and of course the two are quite different. Which is better we'll never know. This one, at least, has made it to the finish line.

Permalink | Read 3432 times | Comments (2)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] The Leon Project: [next] [newest] 95 by 65: [next] [newest]

Thanks to Katie of Peace on Birth, I bring a simple smile to your day. This is especially for those dear to us who are expecting their fourth child and live in a two-bedroom apartment, and for those who passed the family-of-six point quite a while ago. :) He's a little too hard on fathers, but you can tell he doesn't really mean it, just poking fun at himself to make a point. I'd never heard of Jim Gaffigan, but that's a name I'll be alert to from now on. There are some things he gets that few commedians do. I do wish he'd stop with the singular use of "they," however. I mean, he's talking about mothers. I think he could use "she" without excluding anyone.

Permalink | Read 2278 times | Comments (5)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

But pleasantly so. After all, it's a sunny 39 degrees. In contrast, my weather stickers report the following:

- Downingtown, PA: 7 degrees

- Emmen, Switzerland: 8 degrees (6 hours later in the day)

- Granby, CT: 1 degree

- Old Saybrook, CT: 1 degree

- Salem, CT: 1 degree

and the winner is...

- Hillsboro, NH: -10 degrees!

Permalink | Read 2430 times | Comments (1)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

You'd be shocked at the number of people who think our daughter and her family live in Sweden. Just as homeschoolers know that they will inevitably and repeatedly be asked the S Question ("But what about socialization?"), the Swiss know that much of the world will always think they live in the land of IKEA, ABBA, and free health care. Thus I was not surprised to see the following in an article on the Cooking Light website.

First Up: You'll love this Rösti Casserole with Baked Eggs. We have whittled down the calories in this traditional Swedish dish and added our own spin with Greek yogurt and artisan spices. This dish embodies the alluring qualities you'd expect from rösti—shredded potatoes that are cooked until browned and crisp on the edges. Serve with a colorful mixed greens salad.

At least the Swiss won't have to be annoyed at the alterations to their traditional dish—they can blame it on the Swedes.

The two best things about Geneva, Florida may be our friend Richard and the Greater Geneva Grande Award Marching Band, but thanks to Jon I've discovered a third: Stephen Jepson. Take time to watch this Growing Bolder video. It's less than eight minutes long and will show you why I'm enthusiastic about this 73-year-old man's ideas.

I'm looking forward to exploring his Never Leave the Playground website. After watching the Growing Bolder interview, my only negative reaction was that keeping so mentally and physically fit takes up so much of his time he can't possibly fit in anything else, and few people can (or would want to) live that way. But clearly that's not true—he's an artist, an inventor, and a motivational speaker—and his website promises you can begin with easy baby steps.

I wonder if we've passed him among the spectators at our Independence Day parades. Nah, he'd more likely be in the parade himself. But I'll keep my eye out this year for someone juggling on a skateboard.

Legally Kidnapped: The Case Against Child Protective Services by Carlos Morales (Amazon Digital Services, 2014)

Legally Kidnapped: The Case Against Child Protective Services by Carlos Morales (Amazon Digital Services, 2014)

Legally Kidnapped is probably good for any parent to read who either (1) has childrearing philosophies and/or practices that differ at all from the current norm, or (2) thinks they might at some point tick off a family member, friend, or neighbor. There are frightening abuses taking place under the authority of Child Protective Services (name varies by state), where vulnerable children are ripped away from their families for days, months, or years, and for no reason other than ignorance and reasonable philosophical differences. The author says, and I believe him, that "children are much more likely to be kidnapped by State workers than by strangers."

It happened here just a few months ago, basically because the mother was a vegan. A doctor friend in New York told me (without names, of course) of testifying in favor of a family whose children had been taken from them: the excuse was an infected cut, but he said the real reason was the animosity of the social worker to the family's religion. And it's not just in the United States: Germany and Sweden have separated children from their families simply because they were being educated at home. It is a problem, and Carlos Morales, a former CPS agent who knows the system from the inside, offers some helpful information to educate, inform, and assist parents who might find themselves at risk. Some of the most important: record (preferably video) all encounters and interviews, never let your children be interviewed alone, always be calm and polite.

That's the good news. Sadly, I can't really recommend the book. The author, perhaps driven by guilt because of his former complicity, is too strident and extreme. He could have used some of his own advice about being calm and polite. Also, the book is replete with basic punctuation and typographical errors, which rightly or not steal credibility from its message.

Still, if anyone wants to glean what is good, it's short (95 pages), the price is reasonable ($2.99 Kindle price on Amazon, and I got it free when they were running a special), and Amazon tells me that I can lend my Kindle copy out one time for 14 days at no charge.

I hope you all had a very merry Christmas. Ours began with a live cello carol concert and included the opportunity to serve Christmas dinner at the community kitchen where my nephew volunteers. Although the church was packed, there were actually more hands than work to do, so after a while Porter and I found ourselves part of the entertainment: singing Christmas carols for an appreciative audience. That was great fun, though pehaps a litte too much of a workout for my throat. Now we're enjoying the peace and rest of a Christmas evening at home.

But on to the business at hand.

I may have to amend this if I finish another book before the end of the year, but since I made my 52-book goal and have lots of other things going on this week, I'm going to go ahead and publish my 2014 reading list post now.

It's amazing that I can read at a pace of a book a week and still make so little progress on the shelves and shelves of unread books lining our walls. Some are gifts, some are books I bought because they looked promising, and most are from the many boxes of books I brought here when my father moved out of his large home into a small apartment. All of the books are ones I want to read, eventually. But a book a week is only 52 books read in a year, and what with all the new (to me) interesting books that come to my attention, plus books that are so good I want to reread them on a regular basis, the "unread" stack is growing rather than diminishing. Yet I keep on keeping on.

One particular feature of 2014 was the beginning of my determination to read all of the books written by Scottish author George MacDonald, in chronological order of their publication. This is an ongoing project, as there are nearly 50 books on that list. I didn't make this decision until April, which resulted in my reading a one of the books twice—once early in the year, and once when it came up in its chronological ranking. I have no problem with that.

I own beautiful hardcover copies of all these books, a wonderful gift from my father, collected over many years. I would prefer to be reading them book-in-hand, with my family all reading around me, enjoying a toasty fire in the fireplace or cool back-porch breezes. But in reality, this year I have read most of the MacDonald books on my Kindle (or the Kindle app on my phone), in spare minutes snatched here and there from a busy life, or in the few minutes between crawling into bed and falling asleep. George MacDonald's books are public domain and thus free on the Kindle, and are very good material with which to end the day on an uplifting note. This also liberates other time for reading books that I only have in physical form.

Here's the list from 2014, sorted alphabetically. A chronological listing, with rankings, warnings, and review links, is here. I enjoyed most of the books, and regret none. Titles in bold I found particularly worthwhile.

- 2BR02B by Kurt Vonnegut

- Adela Cathcart by George MacDonald

- Alec Forbes of Howglen by George MacDonald

- Annals of a Quiet Neighborhood by George MacDonald

- At the Back of the North Wind by George MacDonald (read twice)

- The Blue Ghost Mystery: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #15 by John Blaine

- The Brainy Bunch by Kip and Mona Lisa Harding

- The Caves of Fear: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #8 by John Blaine

- David Elginbrod by George MacDonald

- The Egyptian Cat Mystery: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #16 by John Blaine

- The Flaming Mountain: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #17 by John Blaine

- The Flying Stingaree: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #18 by John Blaine

- The Golden Skull: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #10 by John Blaine

- Guild Court by George MacDonald

- Handel's Messiah: Comfort for God's People by Calvin R. Stapert, audio book read by James Adams

- Half the Church by Carolyn Custis James

- The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien

- The Jungle by Upton Sinclair

- Life of Fred: Australia by Stanley F. Schmidt

- Life of Fred: Cats by Stanley F. Schmidt

- Life of Fred: Dogs by Stanley F. Schmidt

- Life of Fred: Edgewood by Stanley F. Schmidt

- Life of Fred: Farming by Stanley F. Schmidt (all the Life of Fred books are worthwhile, but I particularly enjoyed Edgewood and Farming)

- The Life of Our Lord by Charles Dickens

- The Locust Effect by Gary A. Huagen and Victor Boutros

- Melancholy Elephants by Spider Robingson

- The Miracles of Our Lord by George MacDonald

- The Mysterious Affair at Styles by Agatha Christie

- Not Exactly Normal by Devin Brown

- The Peculiar by Stefan Bachmann

- Phantastes by George MacDonald

- The Pirates of Shan: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #14 by John Blaine

- The Portent and Other Stories by George MacDonald

- The Princess and Curdie by George MacDonald

- The Princess and the Goblin by George MacDonald

- Ranald Bannerman's Boyhood by George MacDonald

- Robert Falconer by George MacDonald

- The Scarlet Lake Mystery: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #13 by John Blaine

- The Seaboard Parish by George MacDonald

- The Secret Adversary by Agatha Christie

- The Shadow Lamp by Stephen R. Lawhead

- The Silent Swan by Lex Keating

- Smuggler's Reef: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #7 by John Blaine

- Something Other than God by Jennifer Fulwiler

- Sometimes God Has a Kid's Face by Sister Mary Rose McGeady

- Station X: Decoding Nazi Secrets by Michael Smith

- Unbroken by Laura Hillenbrand

- Unspoken Sermons Volume I by George MacDonald

- The Vicar's Daughter by George MacDonald

- The Wailing Octopus: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #11 by John Blaine

- Wool Omnibus by Hugh Howey (Wool 1 - Wool 5)

- Your Life Calling by Jane Pauley

Onward to next year!

I'll say more later about the extraordinary television show NCIS, which has captivated me in recent months, but can't wait for a major review to comment on yesterday's show, House Rules. This is the 12th season of NCIS, so there have been many, many episodes, and with the exception of a couple of this season's, we've seen them all. House Rules ranks as one of the all-time most beautiful. It was their Christmas show, and I don't believe I've ever seen a show that captured the basics of the holiday more effectively, efficiently, and beautifully. It's all there: law, grace, repentance, redemption, fatherly love. It's really an amazing show. The only thing that keeps me from unequivocally recommending it is that I fear that much of the effect would be lost on those who are not long-time viewers. The flashbacks and tie-ins to previous shows that are part of what makes it so powerful would seem disjointed and confusing to those without the proper background.

But I'm in awe of the writers and actors who made it happen, and glad we took time out of a busy holiday schedule to experience it.