I've been told it's a peculiar affliction, but I've always enjoyed listening to beginning Suzuki music students. There's a warm place in my heart for the Book 1 repertoire, both piano and violin. I'm not a music teacher of any kind, but recently I had the privilege of introducing my six-year-old grandson to pre-Twinkle and Twinkle on the violin. He has been taking piano lessons with his other grandmother for a year, and his mother laid the foundations for violin playing with him, so I was able to step in and reap the benefits of a prepared and eager student.

It was glorious. I can't begin to describe how much fun it was. He's very responsible with his half-sized violin, and the need to put it away carefully did not deter him in the least from getting it out several times a day, begging me to teach him something new. He has a good ear and an observant eye, and catches on very quickly.

His excellent violin is a gift from his aunt—it was hers during her Suzuki days—and has only a first finger tape on the fingerboard, she having passed the beginning stages with a smaller size. When it was time for him to learn a song involving the second and third fingers, I explained that he could use his ear to help him find the right finger placement, or I could put on some additional tapes. He asked for the tapes. While I was searching the house for appropriate materials, I suggested he listen to the piece and see what he could figure out on his own. As I was returning with scissors and tape, I could hear him playing: playing the whole phrase in perfect tune.

I put the tape away. He's not always perfect by any means, but if the note is off he's learning to notice and make the correction. I find this awesome.

I know most people aren't as enamored of beginning violin music as I am, but there are some relatives who might enjoy the following. The first is a pre-Twinkle piece called See the Pretty Flowers, and the second is the first Twinkle variation. The videos were made after he had practiced the pieces maybe half a dozen times.

The sad part is that for most of the year we're 1300 miles apart, so teaching him is a rare and special privilege. It's a relay, and I've handed the baton back to his very capable (though very busy) mother. Too bad his aunt—who is both a music teacher and a violinist—is almost three times as far away as I am.

When Life and Beliefs Collide: How Knowing God Makes a Difference by Carolyn Custis James (Zondervan, 2001)

When Life and Beliefs Collide: How Knowing God Makes a Difference by Carolyn Custis James (Zondervan, 2001)

As I mentioned before, I first read When Life and Beliefs Collide in personal circumstances that led to a great reluctance to tackle any of the author’s excellent subsequent books. Only a few years previously, we had left the church which remains to this day both our best and our worst church experience. Because James’ husband was in the leadership of what had become (or revealed itself to be; I’m still not certain which) an oppressive, even abusive situation, I had assumed that he and his family were in agreement with and partially responsible for the oppression. This was confirmed in my mind when I read glowing, positive comments about “our church” in When Life and Beliefs Collide. Re-reading it now, I’m amazed at how effectively that blinded me to the strengths of the book, how bold it was, and indeed how much of a risk James took in writing it.

This is a “women’s book,” written as it was in a situation where women, no matter how qualified, did not teach men, but as theologian J. I. Packer said, “[This] book seems to me to be a must-read for Christian women and a you'd-better-read for Christian men, for it gets right so much that others have simply missed.” The heart and soul of James’ work is the importance of theology in the lives of everyone: male and female, young and old. Don’t let the word scare you into thinking this is a dry, academic subject: as James says on the masthead of her website, the moment the word “why” crosses your lips, you are doing theology.

James makes many excellent points, every single one of which I missed the first time because of the prejudice I brought to my reading. Mighty scary, that.

As usual in my reviews, the following quotations are not meant to be a summary of the book as a whole, but are instead ones that struck me for one reason or another and which I want to remember.

Many Christian men seek wives who know far less than they do or who have little interest in theology. The assumption is that a woman who knows less will make a better wife. Her ignorance will be an asset to the relationship, or as another woman put it, “The less a woman has in her head, the lighter she is for carrying.” This assumption leads women to conclude that the godly thing to do is hold back for his sake. And so the age-old game carries on—a woman keeps herself in check to make a man look good. It happens all the time.

How differently the Bible portrays women. There they are admired for their depth of theological wisdom and their strong convictions. Women in the Bible did not need anyone to carry them. Their theology strengthened them to get under the burden at hand. Contrary to current fears, these wise women did not demean, weaken, or overthrow the men. They empowered, strengthened, and urged them on to greater faithfulness and were better equipped to do so because of their grasp of God’s character and ways.

Far from diminishing her appeal, a woman’s interest in theology ought to be the first thing to catch a man’s eye. A wife’s theology should be what a husband prizes most about her. He may always enjoy her cooking and cherish her gentle ways, but in the intensity of battle, when adversity flattens him or he faces an insurmountable challenge, she is the soldier nearest him, and it is her theology that he will hear.

Glory is the uncovering of God’s character—the disclosure of who God is.

I love that last quote. I haven't thought much about it yet, but if it's a reasonable description of what is meant when the Bible talks about God's glory, many Biblical passages suddenly make a lot more sense, particularly the ones that appear to show God as a petty tyrant, concerned most of all with making himself look good at others' expense. (More)

Priscilla Dunstan is a super-hearer with a photographic memory for sounds. What this did for her when she became a mother could be a breakthrough for all newborns and the parents they are trying to train. (Many thanks, Jon, for the link.)

Permalink | Read 2974 times | Comments (6)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Don't miss the latest post from the Occasional CEO. I don't have time now to summarize it, so you'll have to read the whole thing, which you should anyway. Here's a teaser:

I truly appreciate software. I also love my cotton Hanes, sugar on my Grapenuts and enough gas to get to the beach this summer. But, if there’s nothing else three centuries of sugar, cotton and oil have taught, it’s that first we own the advantaged commodity, and then it owns us.

Permalink | Read 2246 times | Comments (1)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

For the sake of all else I have to do, I took the Front Porch Republic off my feed reader, but I still get, and read, their weekly updates. Which means that sometimes ... often ... I get caught. This time it was a piece by Anthony Esolen, who turns out to be the author of Ten Ways to Destroy the Imagination of Your Child, a book highly recommended to me but which I still haven't read, though I have requested that our library order it. I hope they acquiesce, because reading just one of Esolen's essays made me long for more. Hence less was accomplished this day than intended....

What I read in this week's FPR update was Play and No Play, which is but the latest in a series entitled Life Under Compulsion. Of course I then had to read the whole series:

2012-10-08 Life Under Compulsion

2012-10-22 From Schoolhouse to School Bus

2012-11-06 The Billows Teaching Machine

2012-11-19 If Teachers Were Plumbers

2012-12-03 Human-Scale Tools and the Slavish Education State

2012-12-17 Curricular Mire

2012-12-31 Bad Universality

2013-01-21 The Dehumanities

2013-02-11 The Itch

2013-03-11 Music and the Itch

2013-05-13 Noise

2013-06-10 Play and No Play

It's not as if I want to suck up all your time, too—but it wouldn't be time wasted. You can always quit after the first one....

You have to crawl before you can walk.

Except that you don't. Some babies roll, some scoot on their bottoms, some never develop a nice, clean, cross-pattern crawl (or "creep" to use the technical term), and most of them still learn to walk. Do they suffer later in life for the lack of crawling? Officially, doctors no longer think so, and have removed crawling from the list of important childhood milestones. Based on my own observations over a long life, and on much reading on the subject, I think they're wrong. It is no less than hubris to decide that a normal part of human development is not important, and most systems we used to think vestigial—tonsils, for example—turn out to have a distinct purpose and function. We can live without tonsils; many do, and for some their presence does more harm than good, but that doesn't mean we should excise them from healthy children, as was common half a century or so ago. The burden of proof for crawling's importance should be on those who insist it isn't, not the other way around, and "we see no evidence that crawling matters" isn't good enough for me, especially since there are plenty of therapists who disagree.

But I'm no doctor, and I'm not going to take on the American Academy of Pediatrics here, not now. What I view as blatantly irresponsible, both on the part of doctors and on that of writers like Nicholas Day, whose article deriding the importance of crawling hit our local paper recently, is the reason and the timing behind this change.

Since the implementation of the Back-to-Sleep campaign, in which parents are intensely pressured not to let their children sleep on their stomachs for fear they might die of SIDS, the age at which babies are meeting the customary developmental milestones has increased, and more and more children are skipping the crawling stage. It's not that doctors don't notice: as one said, after the mother fearfully confessed that her child had always slept on his tummy, "I knew that. Look at his head shape! Look at how advanced he is! This is no back-sleeping baby." But few dare not to push Back-to-Sleep.

Nor am I recommending tummy-sleeping here. If I did, I'd hear immediately from my brother in the insurance business. It's a personal, parental decision, best reached by careful research and deliberate decision, although I have known of babies who have made the decision themselves, by flatly refusing to sleep in any position other than prone. Parents are only human.

Besides, I no longer think Back-to-Sleep is the chief culprit here, except insofar as it makes parents afraid to put their babies on their stomachs at any time. This is not the first time doctors have insisted that there is a right way for babies to sleep: When my eldest brother and I were born, it was important for us to be on our backs "so the baby won't smother." By the time my next two siblings came around, tummy-sleeping was pushed, "so the baby won't spit up and choke." None of us had any trouble learning to crawl.

Here's what I think the critical difference is: although there were a few baby-entertainment devices back then—I had a bouncy seat and my brother an early Johnny-Jump-Up—we didn't spend a lot of time in them. A baby on his tummy learning to crawl is a baby learning to entertain himself, and a self-entertaining baby is critical to a parent's sanity. It takes a lot of work to learn to propel oneself forward to a toy one has accidentally pushed out of reach, but babies are hard workers when motivated. Today, the goal seems to be to sell more baby equipment to make the job easier by keeping both the kid and the toys corralled, so they don't have to work (i.e. become frustrated and cry) to reach them. That's easier for the parents, too, but in the same pernicious way that plunking children down in front of the television for entertainment also makes a parent's life easier—in the moment.

I won't even get into the amount of time children these days spend strapped into car seats, where they can barely move. And we used to think the Native American habit of confining their babies to cradle boards was cruel. Car seats, entertainment devices, strollers—sometimes all three wrapped into one so the baby doesn't even get freedom of motion in transfer—the proliferation of these is keeping our babies off the floor, and not crawling.

Bottom line: American babies are not meeting the traditional developmental milestones because of lack of opportunity. So what do we do about it? We change the milestones.

New York State students are failing the math Regents exam? We make the questions easier.

SAT scores have fallen? We "re-center" them, to reflect the lowered average.

Florida schools can't meet the new standards? We lower the standards.

High school students can't handle your tests? Give them easy extra-credit work to pull up their grades.

America's children can't seem to leave the nest and support themselves, even after college? Force their parents to pay for grad school, and to keep them on their own insurance policies until they're 26.

From birth through extended adolescence, we keep lowering the bar for our children. Some day they may forgive us, but I wouldn't blame them if they don't. It is good to recognize that "normal" is a range, and relax about minor variations in timetable and achievement. It is appalling, however, to respond to a general decline by redefining normal as average, and lowering the bar. Again.

Our children deserve a better future than we are preparing them for.

Permalink | Read 2529 times | Comments (3)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

This was posted at Free-Range Kids this morning, and I can't resist sharing it. I have no love for Allstate, but insurance companies know the risk/benefit business better than anyone else, and this is just great.

Permalink | Read 2715 times | Comments (1)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Difficult Personalities: A Practical Guide to Managing the Hurtful Behavior of Others (and Maybe Your Own) by Helen McGrath and Hazel Edwards (The Experiment, 2000, 2010)

When I was in college, I remember this complaint from the psychology majors: taking the required Abnormal Psychology course convinced them that they—and all their friends—were abnormal and psychotic. Reading Difficult Personalities is like that, or like reading a list of symptoms and convincing yourself that you have some deadly disease. The book is an exhausting, if not exhaustive, description of difficult personality types, and it's impossible not to think, "Oh, that's just like him," "She does that all the time!" and "Oh, no! Is that really what I'm doing to others?" Worst of all is the section on the sociopathic personality, which will have you seeing sociopaths around every corner and looking askance at those you think you know best. That may be a slight exaggeration, but it's pretty scary to realize that most sociopaths are hard to identify before it's too late and they've done extreme damage.

What makes the book more useful is realizing its limitations. In this I was saved before the page numbers got into double digits, since the section on signs of extroversion includes that extroverts "tend to think out loud. In talking, they find out what they think," and "often interrupt without realizing that they are doing it." That is such an accurate description of dyed-in-the-wool introvert me that I wasn't a bit surprised to find that not only I but nearly everyone I know has some characteristics of most of the personality categories the authors analyze, even those that appear to be polar opposites.

Although meant to be accessible to a lay audience, the book reads more like a textbook: quite technical, and frequently referencing the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. I think it might be more useful as a reference book than as one borrowed from the library for casual reading. There are many suggestions for (1) dealing with someone who exhibits difficult personality traits (especially in the workplace), and (2) controlling one's own quirks and minimizing the damage done to others. If I knew that I, or someone else, was clearly struggling with a particular problem, I might find the suggestions useful, but short of that I find the content far too broad—even contradictory—and overwhelming. The authors do give some real-life, specific examples, but the book could use a lot more of them, and more examples of successful ways of dealing with problems, rather than just delineations of the problems themselves.

Traits covered include Extroverts and Introverts, Planners and Optionizers, Thinkers and Feelers, Negativity, Superiority, Bossiness, The Anxious Personality, The Inflexible Personality, The Demanding Personality, The Passive-Aggressive Personality, The Bullying Personality, and The Sociopathic Personality. Each is discussed in terms of how normal people exhibit these traits, what is typical of someone for whom this is a significant pattern of behavior, what the person is thinking as he acts in that way, reasons behind such behavior, strategies for dealing with someone of this personality, and strategies for changing your own behavior if you see the trait in yourself. Sometimes the authors point out the positive side of a particular disordered trait as well.

Here are a few quotations, in no particular order and of no particular importance other than they were the ones I typed up before getting tired of the exercise.

Some people prefer a relatively decisive lifestyle in which events are ordered and predictable. ["Planners"] prefer to have closure and structure in their lives and make reasonably speedy decisions in most areas.. Deadlines are kept. They like structure, routine and order, and they plan to make their lives reasonably predictable.

Others have a preference for a less structured and ordered lifestyle, characterized by keeping their options open. ["Optionizers"] are reluctant to make decisions, always feeling they have insufficient information and that something better might come along. An optionizer prefers a lifestyle that is flexible, adaptable, and spontaneous, and not limited by unnecessary restrictions, structure or predictabillity.

I sent the following quote to Lenore Skenazy of Free-Range Kids, who is always berating "worst-first thinking." Turns out it has a psychological category all its own.

Protective pessimism can take many forms, but essentially it is about always assuming the worst will happen and behaving accordingly. Protective pessimists believe that if something can go wrong, it will. If something bad can happen, it will happen, and it will happen to them. Rarely do they expect good outcomes. So they miss out on the joy of anticipation and dwelling pleasurably on the "nice" aspects, in case the gap between pleasurable "dreams" and the reality is too great. They are not game to tempt fate by hoping, dreaming, or wanting, in case they get caught unprepared by negatives. They prepare for disillusionment, sadness and tragedy by protecting their projections with pessimism so they will not get caught by future disappointments. Instead of living up to expectations, they live down, and are often negative in other ways. Other people don't like being around pessimistic people because they can be contagious.

Mistakenly, bullies are often perceived as poor souls with a marked inferiority complex and low self-esteem who bully others because of inadequacy. Research, however, suggests that few playground or workplace bullies are like this, although domestic bullies may be. Bullies were once believed to be socially inept oafs, but research now confirms that they are more likely to be highly skilled people capable of sophisticated interpersonal manipulation of others. They can send a victim over the edge without anyone seeing the "pushes" they use.

Only about 5 percent of the population has such severe problems with anxiety that their behavior would meet the criteria for a diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder. ... However, research suggests that maybe up to 30 percent of the population has an anxiety predisposition, that is, a mild to severe tendency to magnify threat and, too readily, release adrenaline and other fear hormones into their bloodstreams. They often feel stressed all day with no real justificaton.

Early experiences of fearful situations can then create minds that are biased toward exaggerating the potential for danger. They remember every frightening experience and, on being exposed again to similar situations or reminders of those situations, retreat from the threat or freeze in fear. ... [W]e have termed these people flooders as they are often flooded with fear.

- Flooders have a hair-trigger response to any situation that they perceive to be threatening, even if sometimes they are not verbalizing to themselves that a situation is actually threatening.

- They experience fear reactions to a great many situations that others would not interpret as threatening. Because their body is often awash with fear, they train their brains to retain fearful memories, to selectively attend to potential threat, and to overinterpret situations as threatening.

- They tend to be less able to "turn off" the fear hormones once they are discharged into the bloodstream. It can take up to 60 minutes for the body to return to normal after a strong adrenaline surge, and flooders have often had several surges in a row without realizing it.

That hit home to me more than anything else in the book. Most of the authors' suggestions for dealing with the problem, such as "focus on facts and statistics to reassure yourself that the likelihood of a particular danger is less than you believe it to be," I don't find to be of much help. I know that. But in the fraction of a second it takes my body to react to the ringing of the phone, a loud noise, or even the quiet but potentially painful words, "we need to talk," there is no room for rational thought. I know that it's only a very small portion of phone calls that bring me news of death or disaster, that most loud noises are harmless, and that few conversations actually require me to make difficult decisions or accept painful criticism. But that knowledge only allows me to begin the process of calming the fear reaction after it has begun; it's not preventative.

["Successful sociopaths"] are no less sociopathic than the "unsuccessful" type, they just do it differently. There is often no violence involved, although some pay others to be violent on their behalf. They differ from the "unsuccessful" category in that they are adaptive, that is, they have enough skills and advantages to be successful by honest effort if they choose. But they don't. Out of greed, an overwhelming drive for power, and a thrill-seeking orientation, they choose deceit and dishonesty instead. They are more likely to get away with their sociopathic behavior for a long period, as they are often charming, well-networked, and know how to exploit the system. Their associates often cover for them, not realizing the extent of their antisocial and exploitive orientation. ... Sociopathic patterns of behavior are found in many powerful individuals who achieve political, entrepreneurial, sports, and business success. But their behavior threatens the safety, well-being, and security of individuals, businesses, and our overall society.

One other thing I learned from Difficult Personalities: As I had suspected, psychologists think we're all crazy, and the line between normal and abnormal is only a matter of degree. It reminds me of a brain developmental specialist who said that everyone is brain-damaged, but it's more obvious in some than in others.

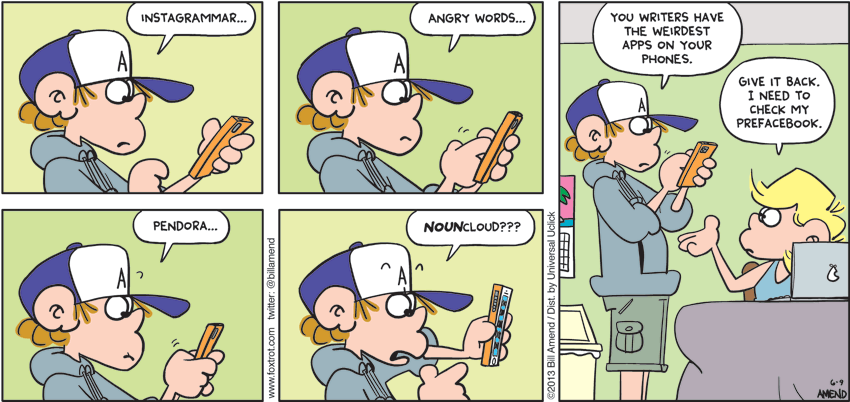

Still love FoxTrot.

Permalink | Read 2164 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Most of you know that I'm not fond of Presbyterian sermons. In my experience, even if they're good they're too long, because the preacher says everything three times. But I'm posting this for three reasons:

- It's local: First Presbyterian Church of Orlando. It was never our church, but both kids had musical gigs there at one time or another.

- It's fascinating: I'd never have guessed this was a Presbyterian preacher. Baptist maybe. Even Pentacostal. But Frozen Chosen? Nah.

- It's a good take on the whole egalitarian/complementarian debate, with points for both sides.

Do I agree with everything? Rhetorical question. You know I never do. But you know there must be something to it if I think a sermon that long is worth listening to.

Permalink | Read 2920 times | Comments (1)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I suppose that title requires some explanation. I don't wish any of our grandchildren harm, but I do wish for them a better good.

Jonathan (age 9 1/2) and Noah (almost 7) have it pretty bad: poison ivy over much of their bodies, faces red and swollen and bound to get worse when the blisters come. I'm not happy that they're suffering.

But they've seen a doctor, who was not at all concerned; they've started treatment, which should help a lot; and they seem to be weathering it surprisingly well (being not nearly as wimpy as their grandmother when it comes to anything skin-rash-related). Therefore I feel free to be delighted at this evidence that life for them is an adventure.

Physically, they were only in their backyard, but who knows where they were in their imaginations? Whatever the adventure was, it required bows and arrows. At some point, both Native Americans and English longbowmen learned that you don't use poison ivy vines for bowstrings, and that if you use your teeth in place of a knife, you'd better know what it is you're cutting into. Jonathan and Noah know that now, too.

They also know that adventure entails risk, and sometimes you get hurt. To be honest, this is not the first time they've learned that particular lesson. My hope is that with each small risk and each small hurt they develop not only muscles and grit, but also discernment, so that by the time they are teens they have a good idea how to tell a reasonable risk from a stupid one.

The following is a multi-hand story. I no longer remember which of my blog- or Facebook-friends pointed me to Brave Moms Raise Brave Kids, though now that I've found it again through a Google search on a phrase I remembered, I'm guessing it was something on Free-Range Kids. It turns out that the story wasn't the author's anyway; her source was a sermon by Erwin McManus. (Don't expect to get much from that link unless you're a subscriber of Preaching Today.)

The gist of the story is this: McManus's young son, Aaron, came home from Christian camp one year, frightened and unable to sleep because of the "ghost stories" told there about devils and demons. He begged his father not to turn off the light, to stay with him, and to pray that he would be safe. Here's his father's unconventional response:

I could feel it. I could feel warm-blanket Christianity beginning to wrap around him, a life of safety, safety, safety.

I said, "Aaron, I will not pray for you to be safe. I will pray that God will make you dangerous, so dangerous that demons will flee when you enter the room."

There's nothing wrong with praying for safety. I pray constantly for the safety of those we love, and of others as well. But McManus's point is well taken: Safety is not much of a life goal. I want our grandchildren (boys and girls) to grow up dangerous to all that is evil, and to all that is wrong with the world.

Sometimes poison ivy is just poison ivy, but sometimes it is warrior training.

Asian buffet restaurants are kind of like IHOP as far as I'm concerned: you need to go there every few years to remind yourself of why you don't go there more often. The idea always sounds so good ... and the reality always disappoints.

We had a coupon for the new World Gourmet restaurant in town, so we went there after church on Sunday. (The link is to the one in California, but it looks like the same thing.) You can't say they don't have variety: I wouldn't go so far as to say world, but there was what I'd call standard American fare in addition to the Asian food. But as usual, the quality just wasn't there, nor can you expect it with all that quantity and variety.

Still, the selection was nice, the honey chicken was especially good, and—when I made a point to be the first one in line when the new batch came out—so were the French fries. Whenever I'm in a place like that, I think of a football-playing friend of Heather's in high school: he could really have done it all justice. Me? I took what I liked, and for once didn't eat too much. Someone has to make up for the football players.

Sunday, June 2: How Great Is Our God (Chris Tomlin, arr. Jack Schrader, Hope Publishing Company, C5491).

(A reminder, for the record: neither of these recordings is of our choir.)

UPDATE 10/25/19: I see that the automated update of Flash to iFrame has once again chopped out a section of the post between the first video and the last line, hence The Gift of Love is missing.