Here Shall I Die Ashore: Stephen Hopkins—Bermuda Castaway, Jamestown Survivor, and Mayflower Pilgrim by Caleb Johnson (Xlibris 2007)

Here Shall I Die Ashore: Stephen Hopkins—Bermuda Castaway, Jamestown Survivor, and Mayflower Pilgrim by Caleb Johnson (Xlibris 2007)

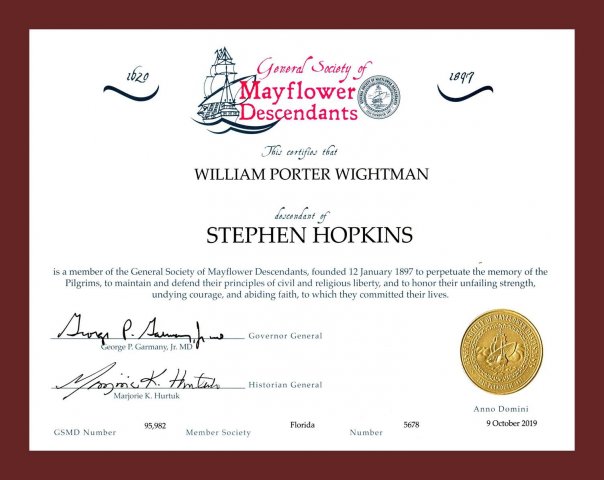

I discovered Caleb Johnson's Mayflower History website while researching for Porter's application for membership in the General Society of Mayflower Descendants. Of the three Mayflower ancestors Porter's family lore put forth as candidates, I chose to pursue Stephan Hopkins soley because that line appeared to be the easiest to document.

MayflowerHistory.com was one of the most interesting sources I found. After some initial skepticism—the value of genealogical information that can be found online ranges from fantastic to abysmal—I recognized Johnson as an authoritative source and entertaining to boot. After proving Porter's descent from Stephen Hopkins to the satisfaction of the Mayflower Society, I gave him Here Shall I Die Ashore for Christmas.

Even before reading the book, I posted a brief summary of Hopkins' life that will give you the gist of his story. But the book is ever so much more than that, a story better told and with more history, context, and detail. I learned a lot I didn't know about the early days of the Jamestown colony in Virginia, and Plymouth in Massachusetts, as well as about Stephen himself.

We all know the Native Americans did not get what they were hoping for out of the arrival of the colonists from England. What I hadn't realized is that nobody involved in these expeditions did. And nobody had a clue how bad the colonists' situations were and how much worse they were going to get. Just when a colony began to (just barely) get a grip on providing food for itself, the folks back in England, frustrated by failed promises of return on their investments, kept sending, not badly-needed supplies, but more hungry mouths to feed. (A number of my own ancestors were on those ships that followed the Mayflower.)

You can't build a healthy colony without women, but women didn't do the kind of work that produced trade goods, so investors were reluctant to allow them to take up space on their ships. It's easy to see the financial backers as heartless, but I'm quite sure most of them were merely clueless. Even in these days of instant communication and near-instant travel, how many of us know what our financial investments—and our charitable contributions—are really doing? And who wouldn't be upset with tenants who don't take care of the property and refuse to pay rent?

Following the initial financial difficulties, long-time Leiden church member and Mayflower passenger Isaac Allerton was appointed to return to England, to start negotiations with the London shareholders and other financial backers. In November 1626, an agreement was reached. The Plymouth colonist-shareholders would purchase the outstanding shares of the company from all the remaining English investors...and assume the colony's debt. The overall adventure was a substantial loss to the London investors—most only got back about a third of their original investment—but the forty-two remaining London shareholders were happy to get out with whatever they could, as most now expected they would eventually lose everything. (pp. 123-124)

Plymouth fared better than Jamestown, thanks to having a population experienced in self-discipline and hard work. Too many of Jamestown's people were of a class accustomed to being served, and whose skills were a very bad mismatch with what the colony needed to survive.

One very important lesson was learned at Plymouth after the ship Anne arrived in 1623, bringing much-longed-for wives, children, and single women.

Up until the Anne's arrival, the Plymouth colonists had worked and farmed collectively; all the crops were brought into a collective company storehouse and then rationed back out to everyone (the employees) in equal allotments. But Governor Bradford and the others soon realized this was not working out as well as had been intended—the productive individuals were getting allotted the same amount as the lazy do-nothings of the colony, and this was killing morale. Bradford's solution: allot everyone their own lots of land, for their own benefit and subsistence. Every person (man, woman and child) received an acre of land, which were logically combined together into larger family plots. (p. 121)

Credit the women, credit free enterprise, or credit finally being out from under the thumbs of clueless managers, but Plymouth finally began to thrive. And so did the Hopkins family.

Most readers will happily stop halfway through the book, where the story of Stephen Hopkins ends. But 115 pages of appendices include much of interest to genealogists and historians, including scholarly articles on the identity and origin of Stephen Hopkins, his descendants to the first three generations, three original-source documents covering Bermuda, Jamestown, and Plymouth, and Stephen's will and estate inventory.

I know I'm a little late for this Thanksgiving wish, since we're now well into Advent and the rest of the country is singing Christmas carols and concentrating on commerce. But on the real Thanksgiving Day we were far too busy indulging in our family's week-long celebration (my grandson's "favorite holiday of the year") to write at that time. (If it looks as if managed to keep up my blogging schedule, that's largely because I had a backlog of posts stored up for the purpose.)

Our missing persons list (always honored on the tablecloth participants sign every year) was longer than usual, but we still numbered over 30 people, and it was SO GOOD to get back to a reasonably normal life again. (If you don't count as abnormal spending most of a day trying to get a COVID-19 test when every source less than a two-hour drive away seemed to be out of stock.)

Holidays rarely retain much of their original purpose, so it's not surprising that Thanksgiving, too, has strayed far from its origins. But no amount of debunking and grinchiness will stop me from recognizing that this year marks the 400th anniversary of the First Thanksgiving. I know that that occasion was hardly unique in being a harvest festival celebration of thanksgiving to God. I know that many descendants of the original Native Americans at that feast wish that their ancestors had been a little less friendly with the Pilgrims. I know that the original looked far different from what is re-enacted in American elementary schools. I know that Thanksgiving didn't become a national holiday till Abraham Lincoln made it so.

So what? That doesn't change the fact that 400 years ago the Pilgrims, having suffered through a tremendously difficult year, gave a feast to return thanks to God for their survival, and shared that meal with their neighbors. We feast in memory of that festival, even if we don't always acknowledge it. And I want our grandchildren to know that if certain of that company had not been among those First Thanksgiving celebrants, they themselves would not be here today.

There were no decorated evergreens in Bethlehem. George Washington didn't refuse to lie to his father about a cherry tree incident. The first Easter had nothing to do with rabbits or eggs or candy. How many people really think about the birth of America on Independence Day, or about workers on Labor Day? Holidays take on a life and spirit of their own, and the alternative to enjoying them for what they are tends to be unhelpful grumbling. I will celebrate all that is good in our modern celebrations, and I will celebrate all that is good about what inspired them.

Happy 400th birthday, Thanksgiving!

Grace Victoria Daley

Born Sunday, October 24, 2021, 12:25 p.m.

Weight: 9 pounds, 9 ounces

Length: 20.5 inches

Mom, baby, and the whole family are doing well and are rejoicing with exceeding great joy over this delightful gift from God.

Based on what I've written before, you can probably guess that I'm fed up with people (and especially organizations) who think they have the right to ask me questions about my race, ethnicity, sexuality, religion, political affiliation, and other personal information on the flimsiest of excuses. I haven't thought of any clever non-answers to most of the questions other than "Decline to Answer," an option that is not always given.

But I'm ready for race/ethnicity/ethnic background.

I've decided I'm Native American.

If you go back far enough, everyone has come to a given place from somewhere else. In my case, I have traced most of my ancestors back to when they first came to North America, and nearly all of their children were born here before the United States of America even existed—often more than a century before. Almost all of my family has been living on this continent for nearly 400 years, and the few "recent immigrants" for more than 200. In genealogical research, there's always room for surprises, but my roots here are very deep and very wide.

That's "native" enough for me.

It won't get me any tribal benefits, but at least it will make answering those pesky questions more interesting.

Well, would you look at that: the feast day of my 28th great-grandmother (and Porter's 26th) is November 16. Monday.

She's Saint Margaret of Scotland (c. 1045 - 16 November 1093).

In my genealogical work I hadn't gotten much further than to place her in my family tree as the wife of Scotland's King Malcolm III (Canmore). Yesterday, however, I was inspired by a friend's question to dig deeper.

Here is a bit about Saint Margaret, from her Wikipedia article. (All quotations are from the article.)

Margaret, also known as Margaret of Wessex, was the granddaughter of English King Edmund Ironside (c. 990 - 1016). She was born in exile in Hungary, her father, Edward the Exile, having been sent away by King Canute after the Danes conquered England. Later she returned to England and grew up in the English court until she fled to Northumbria after the Norman Conquest.

According to tradition, the widowed Agatha [Margaret's mother] decided to leave Northumbria, England with her children and return to the continent. However, a storm drove their ship north to the Kingdom of Scotland in 1068, where they sought the protection of King Malcolm III.

That's Malcolm, son of King Duncan—see Macbeth, though it takes many liberties with history, not unlike today's movies.

Two years later, Malcolm and Margaret married, and she became Queen of Scots.

Margaret [is credited] with having a civilizing influence on her husband Malcolm by reading him narratives from the Bible. She instigated religious reform, striving to conform the worship and practices of the Church in Scotland to those of Rome. ... She also worked to conform the practices of the Scottish Church to those of the continental Church, which she experienced in her childhood. Due to these achievements, she was considered an exemplar of the "just ruler", and moreover influenced her husband and children, especially her youngest son, the future King David I of Scotland, to be just and holy rulers.

[Quoting the Encyclopedia Britannica] "The chroniclers all agree in depicting Queen Margaret as a strong, pure, noble character, who had very great influence over her husband, and through him over Scottish history, especially in its ecclesiastical aspects. Her religion, which was genuine and intense, was of the newest Roman style; and to her are attributed a number of reforms [of the Church in Scotland]."

She attended to charitable works, serving orphans and the poor every day before she ate and washing the feet of the poor in imitation of Christ. She rose at midnight every night to attend the liturgy. She successfully invited the Benedictine Order to establish a monastery in Dunfermline, Fife in 1072, and established ferries at Queensferry and North Berwick to assist pilgrims journeying from south of the Firth of Forth to St. Andrew's in Fife. She used a cave on the banks of the Tower Burn in Dunfermline as a place of devotion and prayer. St. Margaret's Cave, now covered beneath a municipal car park, is open to the public. Among other deeds, Margaret also instigated the restoration of Iona Abbey in Scotland. She is also known to have interceded for the release of fellow English exiles who had been forced into serfdom by the Norman conquest of England.

Margaret was as pious privately as she was publicly. She spent much of her time in prayer, devotional reading, and ecclesiastical embroidery. This apparently had considerable effect on the more uncouth Malcolm, who was illiterate: he so admired her piety that he had her books decorated in gold and silver. One of these, a pocket gospel book with portraits of the Evangelists, is in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, England.

Margaret was canonized in 1250 by Pope Innocent IV.

In the bizarre tradition of fighting over saints' body parts and other relics, my saintly grandmother did not fare well.

Not yet 50 years old, Margaret died on 16 November 1093, three days after the deaths of her husband and eldest son. The cause of death was reportedly grief. She was buried before the high altar in Dunfermline Abbey in Fife, Scotland. In 1250, the year of her canonization, her body and that of her husband were exhumed and placed in a new shrine in the Abbey. In 1560, Mary Queen of Scots had Margaret's head removed to Edinburgh Castle as a relic to assist her in childbirth. In 1597, Margaret's head ended up with the Jesuits at the Scots College, Douai, France, but was lost during the French Revolution. King Philip of Spain had the other remains of Margaret and Malcolm III transferred to the Escorial palace in Madrid, Spain, but their present location has not been discovered.

Saint Margaret of Scotland is said to be the patron of Scotland, Dunfermline, Fife, Shetland, The Queen's Ferry, and Anglo-Scottish relations. I think the last could use a little more attention these days.

Maybe it's a good thing that AncestryDNA's latest revision puts my ancestry at 44% Scottish.

Yes, I am thankful for the rain. I love the thunderstorms with their deluges, normal for this time of year. And I'm grateful for the long, soaking rains of the kind we usually only get when there's a tropical storm off the coast but which have been nearly continuous all summer. The Floridan aquifer really needs the boost.

Nonetheless, I've decided I don't want to live in the Pacific Northwest.

My father's grandfather moved his family from Baraboo, Wisconsin to Sumner, Washington in the early 1890's. Sumner is just outside of Seattle, where it rains on average 152 days a year. So you'd think rain was in our blood. However, my father himself grew up in Pullman, Washington, where his father taught mechanical engineering at what was then Washington State College. Pullman is in the desert side of the state.

We have had so many days of rain this summer that I'm expecting to break out in mushrooms any day now. At the very least a severe case of mildew. After I've been outside for a while, I want someone to pick me up and wring me out like a piece of laundry. With six active tropical storms on our horizon, I don't expect things to dry out anytime soon.

I'm indeed grateful for the rain—and for the roof over our heads and the air conditioner that together provide a refuge that is both cool and dry.

The Lost Family: How DNA Testing is Upending Who We Are by Libby Copeland (Abrams Press, 2020)

The Lost Family: How DNA Testing is Upending Who We Are by Libby Copeland (Abrams Press, 2020)

I been working seriously on genealogical research for almost two decades—the library-and-paper kind, supplemented by the steadily-increasing availability of records online. Then at the end of 2017 we dipped our toes into genetic genealogy, submitting saliva samples first to AncestryDNA, then to 23andMe. There have been a few small surprises, but nothing monumental.

However, my genealogical connections—primarily Ancestry.com and the New England Historic Genealogical Society—frequently send me other people's "DNA reveal" stories: the kind where Holocaust survivors from the same family find each other 60 years later, or adoptees find their birth parents, or people discover that the man they've always called "Dad" has no genetic relationship with them. Mystery, tragedy, triumph—it's all there.

Thus my eagerness to read this book as soon as I heard about it. Our library had already seen the wisdom of having The Lost Family on its shelves; when I looked for it, it was already on order. As soon as it came in, I grabbed it. What with other things to do, it took me three days to devour it.

The Lost Family is actually three books:

- The stories. This is why I wanted to read the book in the first place. Unfortunately, there aren't that many, for all it's nearly a 300-page book. And I guess I shouldn't have been surprised that the biggest story of all, the framework for the whole book, was one I already knew. That was okay; I learned many details that I hadn't known. But I wish more of the book had been dedicated to the real-life stories.

- A good deal of teaching on the science behind genetic testing and DNA analysis. Most of this was old news to me, but it's complicated and a review is not a bad thing. If you're new to the field, it's definitely a good thing.

- A lot of most-unwelcome preaching, filled with identity politics; and how interest in genealogy is racist if you're white though apparently not if you are black; and a confusing section in which the author uses "they" to refer to both a single, transgender person who requested that personal pronoun and to multiple-person groups; and how "race" is a racist concept and "ethnicity" doesn't really exist (and is probably a racist idea, anyway); and how history is fluid and there's no such thing as truth but only your truth and my truth and their truth.

Reading the book was much like eating a meal in which I was repeatedlly given a bite of chocolate cake, then a bite of chicken, then a bite of okra. I know, some people actually like okra. They may even like the political sections of the book. I did not.

In addition, there's a lot of angst and questioning: "Who am I, really?" "What is a family?" "Can I love Irish music if I discover that my heritage is not Irish, as I thought, but Russian?" "What makes me the person I am, my genes or my experiences?"

I'm certain I'd feel more empathetic if I were the adoptee seeking birth parents, or the daughter who discovered her father wasn't the man she thought he was. The personal angle does make all things new. But the nature vs. nurture question has been around as long as we have realized they were separate influences. To me, the obvious answer is "both." End of story. I never imagined anyone would take seriously the AncestryDNA commercial in which a man gets the results of his DNA test and "turns in his lederhosen for a kilt." I never did have patience for the idea that you can only enjoy a culture if you were born into it.

Nor did I imagine that anyone would expect a DNA test to reveal exact genetic origins. Although it's getting better all the time, and is considerably more accurate now than in the early days, it's still part science, part art, and part guesswork. That's made pretty clear if you look into it at all, though I admit the commercials—like most commercials—give a simplified and thus somewhat false impression.

Besides, I hate stories about angst. Romances, coming-of-age-stories—not my thing at all.

Am I glad I read the book? Yes. Am I glad I didn't buy it? Definitely yes. Would I recommend reading it? Well, if you're thinking about taking a DNA test, it's a decent introduction to the art-and-science, and a fair warning that your world could be turned upside down. And the stories are interesting. Overall, yes, I would recommend it.

Some people, after all, even like okra.

There were only six sticky notes marking quotations this time. (At least the book was easier to review!) Bolded emphasis is mine.

At times, the sense of mission among members [of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints] has gotten out of hand, as when members have submitted the names of Jews, including Holocaust victims, for posthumous baptism. (p. 30)

This is typical of an attitude I find puzzling throughout the book. A Catholic who discovers that her biological father was Jewish wonders if she should become Jewish herself, as if one's faith is something inherited rather than a statement of beliefs. I guess this goes along with the "your truth and my truth but nothing is really true" idea. I suppose it's also a sign of someone who hasn't delved too deeply into his ancestry, which would hardly reveal a unanimity of faith.

If you believe, as the Mormons do, that they can save the souls of their dead ancestors through a present-day ceremony, and some of their ancestors happen to have been Jewish, why exclude them from the eternal family? If the Mormons are right, they will be doing those Jewish ancestors the greatest possible favor. If they are wrong, then they are certainly not doing them any harm.

[Describing researchers at a genealogical library] They may be hobbyists or pros; they may travel as groups of genealogical societies, the better to swap stories and resources. They may come from far away—Canada, France, England, New Zealand, all over the United States—and park at the library every day for a full week. Sometimes, people planning to do just a little research stay far longer than they meant to, as if they fall into some kind of wormhole that alters time. This place can do that to you. (p. 31)

So true. She wasn't describing the NEHGS library in Boston, but she might have been.

We're such believers in genes that a recent Stanford University study found that informing people of their genetic predispositions for certain traits—rather, misinforming them, by telling them whether they had certain gene variants associated with exercise capacity and obesity, regardless of their actual results—influenced their actual physiology. Those told they had low-endurance versions of a gene variant did worse on a treadmill test, with poorer endurance and worse lung function (even if they didn't actually have that gene variant). Those told they had a variant that made them feel easily sated felt fuller on average after being given a meal, and tests revealed their bodies had produced more of a hormone that indicates feelings of fullness. By believing they were genetically destined for something, these subjects appear to have made it true. (p. 57)

I love stories of that kind, too.

Europe's market [for DNA testing] is seen as several years behind the US market because of a complex tapestry of policy, pragmatism, and culture. In general, says David Nicholson of UK-based Living DNA, Europeans are more concerned than Americans with matters of privacy and security. (p. 135)

This is a common belief, but I find it to be not so simple. In my limited experience, Europeans are indeed more concerned than Americans about giving their data to businesses, but I think most Americans would be shocked at how much information European governments have on their people, and especially how widespread and well-coordinated that information is. The post office, the train station, the police, the schools, the motor vehicle departments—what one knows, the others know. In the early days of homeschooling, many families were able to "fly under the radar" by never registering their children for school. In Switzerland, the schools know about your children from the day they are born. All that shared knowledge turns out to be convenient at times, but, being an American, I trust knowledge in private hands more than in the hands of the government, because governments have more power. I may hate that Google is so powerful and knows so much about me, but it wasn't Google that with one fell swoop shut down the American economy and separated us from our children and grandchildren.

Roth found that testers who identified as black or African American were far less inclined to incorporate new ancestral knowledge into their identities. In part, that's because they tended to identify strongly and positively with their existing identities; unlike white respondents, they did not describe their race as boring and plain. (p. 167)

Finally, acknowledgement in print of what I experienced in my childhood—at least from fourth grade onward. The worst thing you could be was a WASP: I distinctly remember announcing that since I couldn't help being white and of Anglo-Saxon heritage, I'd have to become Catholic. Even in my tiny, nearly-all-white village in Upstate New York, being white, at least in the dominant school narrative, was associated with being dull, stupid, ignorant, rude, and klutzy. I often wonder why this isn't more universally acknowledged; surely I can't have been the only one to have noticed it.

Alice verified which of the Collins siblings' genetic segments came from their father by matching them against known paternal cousins, and, by putting it all together, she could approximate a good portion of what Jim's chromosomes looked like, effectively raising him from the dead. (p. 272)

Hmmm. Whatever the author's religion is, count me out. I think Christianity offers a far more appealing view of what it means to be raised from the dead. :)

In a comment to my post, Sometimes Old Family Stories Are True, Heather asked, "Speaking of old family stories, what do you know about the truth of the My grandfather saved Einstein from drowning one?

You can see how these legends grow over time, for the story as I know it was not that Bill Wightman saved Albert Einstein from drowning, but that the deed was done by a local "village idiot" named Johnny Dingle.

Here's what I was able to find out with some quick research.

In addition to the stories Porter and I remember hearing from Bill and other Old Saybrook natives, I discovered this in "Charles Griswold Bartlett: Mapping Old Lyme's Waterways," (Old Lyme Historical Society: River and Sound, Issue 12, Winter 2013, p. 5).

A hermit named Johnny Dingle lived on Great Island until September 1938.

Whether or not Dingle was also a bit mentally incapacitated is another issue, though Bill and others certainly described him that way. If nothing else, it provides great contrast in the story about Einstein.

This Patch article, "Sailing the Connecticut Coast with Albert Einstein," shows that an encounter between Dingle and Einstein was not only possible, but likely.

[Albert Einstein] learned to sail in Switzerland as a young man and continued to do so for more than 50 years. ... He rented a home called the "White House" in Old Lyme during the summer of 1935 and took his 17-foot sailboat named Tinef with him.

Despite sailing for over half a century, Einstein was not a very accomplished sailor. According to his biographers, he would lose his direction, his mast would often fall down, and he frequently ran aground and had near collisions with other vessels.

Often sailing near the mouth of the Connecticut River at Old Saybrook, Einstein ran aground on a sand bar once. The New York Times took note, running the following headline in the summer of 1935: "Relative Tide And Sand Bars Trap Einstein." Another newspaper put it this way: "Einstein's Miscalculation Leaves Him Stuck On Bar Of Lower Connecticut River."

Interestingly, Einstein seemed to be indifferent to the dangers of sailing, and the perils were particularly acute since he didn't know how to swim! It is rather amazing that he didn't drown.

Did Johnny Dingle really save Einstein from drowning? It's quite possible that story is true. What's near certain is that Dingle did help out the brilliant scientist one way or another, given the hapless sailor's predilection for getting into trouble, and that Dingle, however challenged he might have been in the rest of life, was constantly on and around the water where Albert Einstein was sailing, and knew well all the shoals, sandbars, and other hazards of his demesne.

I grew up in a family as wonderful and loving as anyone could want. As close as we were, however, we lacked one thing: a sense of family beyond the here-and-now, including any knowledge of our ancestry. In a world where most of my friends knew "where they came from"—their families having emigrated relatively recently from Poland, Italy, England, Canada, South Africa, and more—my parents insisted that we all were Americans and nothing else mattered. We not only embraced America, we spanned it: my father came from Washington in the west, my mother from Florida in the south, and they met in Schenectady, New York. Our cousins were spread all over the map, and back then keeping in touch was not the easy thing it is today.

Not till much later did I realize how rootless this perspective had left me, but it was well-intentioned and possibly a good thing—a vaccination against the anti-immigrant feelings that occasionally troubled the times. Sadly, though, it was half a century later before I developed an appreciation of the importance of learning history.

Porter's family was different. On his father's side, he had two great-grandparents who came from Sweden, and a great-great-grandmother from England, but the rest of his family was well established in Connecticut long before the United States existed. He grew up hearing "old family stories" of the kind that genealogists tend to debunk: We came over on the Mayflower (turns out to be true), our ancestors fought in the American Revolution (also true), I'm part Native American (a very common belief and almost certainly untrue), and the one of importance today: one of your relatives was a friend of Eli Whitney, inventor of the cotton gin.

The last was just one of many lesser family stories I'd heard upon marrying into the family, and I'd filed it away in the back of my mind, along with Superman mowed my uncle's lawn. (That one's also true: Christopher Reeve was a neighbor.) But after reading Eric B. Schultz's chapter on Eli Whitney in Innovation on Tap (review to come), I decided some further research was called for.

The name Whitney appears several times in Porter's recent family history, all close relatives of Hezekiah Scovil (1788-1849) of Haddam, Connecticut, and his wife, Hannah Burr (1794-1859):

- Son Whitney Scovil 1813-1837

- Grandson Whitney Tyler Scovil 1837-1840

- Grandnephew Whitney Scovil 1847-1940

- Grandson Whitney Daniel Scovil 1861-1867

- Great-grandson Whitney Scovil Porter 1886-1958 (Porter's grandfather)

- 4th great-grandson Spencer Whitney Sloane

By itself this is no indication of a relationship with Eli Whitney, but it is suggestive that the name was nowhere in the family before this.

Hezekiah Scovil, Porter's 3rd great-grandfather, was a blacksmith in the small town of Higganum, Connecticut, and he is the connection to Eli Whitney. He apprenticed to Whitney in New Haven, and later manufactured gun barrels for him in his own shop in Higganum. The following story is taken from the Commemorative Biographical Record of Middlesex County, Connecticut:

[Hezekiah Scovil] became acquainted with Eli Whitney, who came to see him at his home, and spent one night with Mr. Scovil. Mr. Whitney was a very tall man, and the following morning Mr. Scovil inquired of his guest how he had rested. Hesitating some little, Mr. Whitney answered the question of his host by saying: "Well, pretty well if the bed had been longer." As the result of this visit Mr. Scovil turned his skill to the making of gun-barrels by hand, power being substituted later on. He went to New Haven, engaged in this work, and then returned to Candlewood Hill, where he made the gun barrels for Mr. Whitney.

Hezekiah had 10 children, the oldest of which was named Fanny. She married John Porter. Their youngest son, Wallace, was the father of Whitney Scovil Porter (#5 above), who was Porter's grandfather and the great-grandfather of Spencer Whitney Sloane (#6).

Those of you who have followed the story of Phoebe's Quilt may be interested to know that the quilt connects here more than once: Fanny was first cousin to the recipient, Phoebe L. Scovil, and it is through Fanny that the quilt came into Porter's family. Phoebe's father was Hezekiah's brother, Sylvester; Phoebe's brother William was the father of the Whitney Scovil who is #3 above.

The first Hezekiah's firstborn son, Whitney (#1 above), was the father of #2, Whitney Tyler Scovil. It is a sad story: Whitney married in January of 1837, and his son was born in November of that year. He himself died the next month, and his son followed in 1840 at the age of two.

Of the original Hezekiah's other children, I will note three. Many of the others died quite young and/or unmarried.

His daughter Josephine died at the age of 48, unmarried—but she is notable because we have her portrait hanging on our living room wall.

Having explained the truth of the old family story connecting Porter's family with Eli Whitney, I'll spend the rest of this post on two of Hezekiah's other sons, Daniel and Hezekiah. Hezekiah was the father of Whitney Daniel Scovil, #4 in the Whitney list above.

Daniel and Hezekiah are the famous names in Higganum, and part of the Eli Whitney legacy, having carried on their father's blacksmithing tradition by creating the D & H Scovil Manufacturing Company in 1844. In addition to manufacturing gun barrels, and lovely things like the two iron candelabra that stand in our house, D & H Scovil made hoes. The "Scovil hoe" is what they are famous for.

Daniel made a trip into the plantations of the South, where he discovered that the English hoes being used there were of terrible quality. Family lore suggests that Daniel might have had a travelling companion, Eli Whitney, Jr.—but I haven't found documentation for that. Daniel put his mind to the problem of building a better hoe, and he did. He designed and manufactured what he called a "planter's hoe," which gripped more tightly on the handle and sharpened itself as it was being used.

Every inventor needs a partner with good business sense, and for Daniel that was his brother, Hezekiah. The hoe was a hit, and a success.

The first four minutes of this video show a Scovil hoe and some of its history and features. The narrator gets a few things (and pronunciations) not quite right, but it's mostly true to what I've learned elsewhere.

Here are some references that might be of interest if you want to dig further:

- Commemorative Biographical Record of Middlesex County Connecticut, Chicago: J.H. Beers & Co., 1903, pp 60-64

- Haddam: 1870-1930, by Charlotte Gradie and Jan Sweet for the Haddam Historical Society, Arcadia Publishing, 2005, pp 94-99 (The Google preview skips several of these pages, but there are some very nice photos if you can see them.)

- The Conneticut Magazine: An Illustrated Monthly, Volume 5, pp 598-500

Finally, if you really want to know the D & H Scovil history, I just found these three presentations given at the Haddam Historical Society, and I'm sure they will be fascinating. I admit I haven't watched them, and I sure hope they don't contradict what I've written. I'm looking forward to seeing them with Porter—maybe I'll make popcorn for the occasion—but it's nearly four hours' worth of material, so that's not going to happen for a while.

A Year in the Life of D and H Scovil – Part 1

A Year in the Life of D and H Scovil – Part 2

A Year in the Life of D and H Scovil – Part 3

There is an interesting postscript to this story. Although Porter's family worked with and was inspired by Eli Whitney, they are not related in any way I could find. My family, however, is! Mr. Whitney and I are second cousins, six times removed.

Who was Stephen Hopkins, the Mayflower passenger who is Porter's 10th great-grandfather?

To me he was just one name out of 15,000 in my family tree database. But having proved his significant relationship to my husband, children, and grandchildren, I thought it best to learn a bit more about him.

Turns out he's quite a character.

It has long been known that he was a passenger on the Mayflower, but only recently has there been good evidence that this was not his first trip to the New World.

Stephen was born in Hampshire, England, in 1581. He married a woman named Mary, and by her he had three children: Elizabeth, Constance, and Giles. Constance is Porter's 9th great-grandmother.

In 1609, Stephen signed onto a ship called the Sea Venture, as a minister's clerk, for a voyage to Jamestown, Virginia. You may recall that the English had settled Jamestown in 1607; this ship was part of a fleet intended to bring settlers and much-needed supplies to the colony. However, the Sea Venture became separated from the fleet in a storm, and was wrecked on Bermuda. Food and fresh water were plentiful and the former passengers survived, led by Thomas Gates, who had been commissioned to become the new governor of Jamestown.

During his life as a castaway, Stephen Hopkins demonstrated the temper for which he was remembered in Porter's family, where outbursts of anger were met with the admonition, "You're behaving like Stephen Hopkins." Or perhaps it was less temper and more independent spirit. In any case, Stephen was vocal about his dissatisfaction with the leadership of Governor Gates, and questioned his authority, leading others to do the same. There's a name for that at sea: mutiny. He was arrested, tried, convicted, and sentenced to death. Thanks to his eloquent pleading and that of others, he was pardoned, and was wise enough in the future to keep his opinions about Governor Gates to himself.

If the name of the ship is familiar to you, you may be a fan of Shakespeare's plays. The fate of the Sea Venture was one of the inspirations for The Tempest, and some think the character Stephano in the play was modeled on Stephen Hopkins.

In May of 1610, having built themselves some new boats, the castaways finally arrived in Jamestown. There they found the colonists starving and dispirited, and determined to depart. Before they left, however, a ship arrived from England with supplies, more colonists, and a new governor. Stephen Hopkins stayed in Jamestown until recalled to England sometime after the death in 1613 of his wife, Mary. He married Elizabeth Fisher in 1617, and they had a daughter, Damaris.

In 1620, Stephen, Elizabeth, Damaris, Giles, and Constance boarded the Mayflower. (Stephen and Mary's other daughter, Elizabeth, had probably died or possibly was married by that time.) They were not Pilgrims, but what the Pilgrims called Strangers, having been recruited in London to assist with a new venture in Virginia. A son, Oceanus, was born to them on the voyage.

As we all know, the Mayflower never made it to the sunny shores of Virginia. Stephen made the best of the situation, signed the Mayflower Compact, and threw himself into the work of the Plymouth Colony, making himself particularly useful by virtue of his previous experience with Native Americans, exploring, and living off the land. When Samoset, an Abenaki Native, startled the colonists by walking into their settlement and speaking to them in English, he spent the night in the Hopkins home.

Stephen and Elizabeth had five more children, born in the Plymouth Colony: Caleb, Deborah, Damaris, Ruth, and Elizabeth. The repetition of names (Damaris, Elizabeth) is usually a good indication that the previous children of those names had died young.

The courts were busy in those days with offenses major and minor, and genealogists are thankful for ancestors who got into a little bit of trouble, because they left records. Stephen Hopkins ran a tavern, and his name appears several times in the court records: for fighting (there's that temper again), for allowing drinking and game playing on Sunday, for allowing people to "drink excessively," and for selling goods for more than the customary price. Also, one of his servants was found to be pregnant by a man who subsequently was executed for having murdered a Native American. The court ruled that Stephen was financially responsible for her and the baby until her term of service was up; instead, he threw her out of the house. Another colonist saved the day by buying out her remaining two years of service and accepting responsibility for her and the child.

Adventuresome, resourceful, independent, competent, fractious, and of fiery temper—that's our Stephen Hopkins. If you wish to read more about him, here are some interesting links:

American Ancestors - Stephen Hopkins

MayflowerHistory.com - Stephen Hopkins

It has been a long time coming.

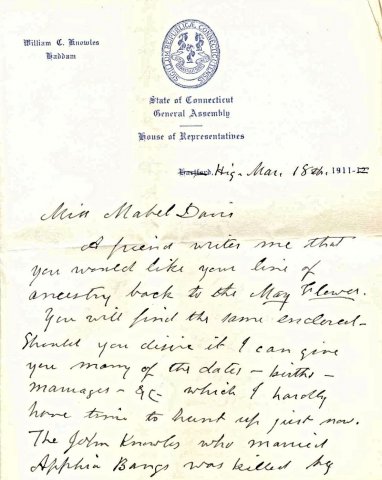

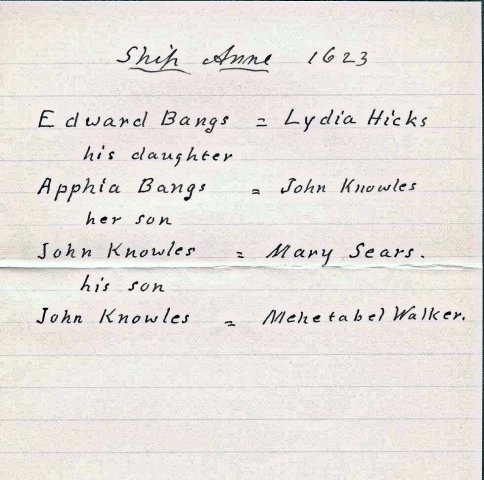

In our family, it began in 1911, with this letter written to Porter's grandmother, Mabel Davis, by William C. Knowles, a member of the Connecticut State House of Representatives. He was her representative, and also a distant relative, but who the friend was who put them in contact we will probably never know. (Click images to enlarge.)

Note his final line: Many are proud of their connection with the Pilgrims. I think they were a cantankerous set. Apparently Stephen Hopkins was cantankerous, at any rate: when Porter was a teenager and let his temper get the best of him, his mother would tell him to stop acting like Stephen Hopkins.

Mabel Davis was 21 years old when she received this letter. As far as we know, she did not apply to the Mayflower or any other hereditary society. She married the following year, and probably found much else that commanded her attention. (Such as bringing the Maggie P. into the family. How much of her personality came from Stephen Hopkins no one knows, but she was a Force to be Reckoned With.)

Many years later, sometime after we first moved to Florida, Porter took up the letter and the genealogical work. However, he also became too busy, and again it languished.

Then came 2002, the year of my father's death, which had followed close on the heels of the death of Porter's mother. I was stunned to realize that most of the people of whom I might ask questions were now out of reach, and the few remaining were well along in years. What's more, it occurred to me that, as the oldest in my family by quite a number of years, I had memories of bygone times that my siblings did not. I had never been interested in history of any sort, but it began to look as if I needed to take action to stem the rapid disappearance of family knowledge.

So I took up the genealogical baton, helped considerably by three significant factors.

- On both sides of the family there had been people of earlier generations who had shown some interest in family history, so I had a few good books and some painstakingly-gathered notes to begin from.

- We were at the time living just outside of Boston, with the tremendous resources of the New England Historic Genealogical Society library just a short train ride away. I can't emphasize enough how important this was to the progress I made. Alas, this season of my research was short, as we moved back to Florida in early 2003, but I made the most of it. In those days before Internet genealogy took off, the books, manuscripts, and human resources of the library were essential; even now, whenever we visit Boston my goal is to spend as much time as possible at the NEHGS. The same is true of New York City: You can have your Broadway shows—give me the New York Public Library's Milstein room.

- While "There's never enough time!" is my constant and continuous refrain, I can't deny that with our youngest child in college, and not being constrained by the demands of employment, the time was finally right for some serious and sustained research.

I took up the baton, it is true, but I ran in my own direction. I grew up with zero interest in family history, and negative interest in heritage societies. My sole desire at that point was to gather data (like Google—data, data, and more data) and to enjoy solving genealogical puzzles. With the help of many people and resources, my family tree grew to nearly 15,000 people. (I hasten to add that this was without tacking on branches from other people's Ancestry.com or Family Search trees, which is how unsourced and incorrect data is spreading like a California wildfire.) I'm still embroiled in the massive challenge of organizing that data and making sure the tree is as accurate and well-documented as possible—as well as continuing to learn more, of course.

Knowing that he had a Mayflower ancestor—actually, at least three different branches that I know of now—Porter expressed an interest in joining the Mayflower Society, because of the upcoming (2020) 400th anniversary of the Landing of the Pilgrims. With all the data I have collected, you'd think that would be an easy job for me to do, so in 2017 I looked into the process and recklessly promised it to Porter as a Christmas present.

But even well-sourced data about a line of descent is not proof, and the Mayflower Society turns out to be particularly rigorous in its requirements. Of Porter's three possible Mayflower lines, I chose Stephen Hopkins because it looked to be the easiest to prove. Maybe it was, but easy it was not.

Now that I've done it once and know the procedures and requirements, it shouldn't take me as long to do another one—assuming the proof is available. (I can't believe I just wrote that; for months I had been intoning, "Never again. Never again. I am never going through this again." I guess it's like childbirth.) This was the gift that kept on giving: Christmas 2017, birthday 2018, Christmas 2018, birthday 2019. We submitted the final application in May of this year, and in October the certificate at the top of this post finally arrived in the mail.

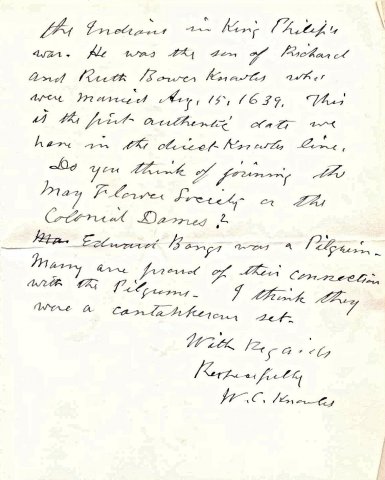

Stephen Hopkins is Porter's 10th great-grandfather. The line is as follows:

Stephen Hopkins—Constance Hopkins—Sarah Snow—William Walker—Mehitabel Walker—Richard Knowles—Mary Knowles—Joseph Burr—Sarah Burr—Julius Davis—Mabel Davis—Alice Porter—Porter Wightman.

As patriarch of the family Stephen naturally gets all the press, but note that in this line Porter actually has two Mayflower ancestors. Stephen's daughter Constance was also a passenger on that ship.

I had figured to use my work once more as a Christmas gift, with the framed certificate wrapped and waiting under the tree. But I soon discovered that I couldn't wait myself—the road had been so long.

And anyway, it's a really appropriate Thanksgiving present.

Hey, Eric! Look what I found in the Summer 2019 issue of American Ancestors!

I haven't had a cartoon published since my Dip City days. Not that this is entirely my cartoon, but it is my caption.

On Facebook, American Ancestors (The New England Historic Genealogical Society) occasionally runs a contest in which readers suggest captions for a cartoon that they plan to publish in their magazine. I had no idea that mine had been chosen till I reached the final page of the most recent issue.

That was a fun surprise!

Porter is now the patriarch of our family. His father died last week, at the good age of 92. We are thankful that he did not linger in a nursing home, and that his mind was still his own even as his body deteriorated. His obituary was published in the Hartford Courant of August 22, 2019. Because the Courant charges a shocking price, I'm publishing the longer (and more genealogically satisfying) version here.

William Stoddard Wightman of Old Saybrook, Connecticut died August 15, 2019 at Middlesex Hospital in Middletown. Born February 21, 1927 in Bristol, Connecticut, Bill was the son of Stoddard Elsworth Wightman and Hilma Louise (Lulu) Faulk. He is survived by a son, William Porter Wightman (Linda) of Altamonte Springs, Florida, and a daughter, Prudence Wightman Sloane (Jay) of Salem, Connecticut, as well as three grandchildren, Heather (Jon) Daley, Janet (Stephan) Stücklin, and Spencer Sloane, and ten great-grandchildren, Jonathan, Noah, Faith, Joy, Jeremiah, and Nathaniel Daley, and Joseph, Vivienne, Daniel, and Eleonora Stücklin. He was predeceased by two wives, Alice Davis Porter of Higganum (1952-2001) and Arline Johnson McCahan (2002-2012), one sister, Elinor (Wightman) (Fredrickson) Fisher, and one great-grandson, Isaac Daley.

Bill enlisted in the Navy the day after he turned seventeen and was trained as a medic for the invasion of Japan, but was “saved by the bomb.” After the service he worked as a shad fisherman and helped Ernie Hull build the marina at Saybrook Point. He then went to Mitchell College and the Rhode Island School of Design, getting a degree in textile engineering. He worked thirty years for Albany International designing paper machine clothing. This gave him the opportunity to work abroad in France, Sweden, Holland, Brazil, and South Africa. He retired in South Carolina in 1982, living there until his second marriage in 2002 when he moved to Old Saybrook. He was an avid sailor and proud owner of the Fenwick cottage, the “Maggie P.” In lieu of flowers donations can be made to the U.S. Navy Memorial in Washington.

As our new rector has taught us, we are bold to say,

May he rest in peace and rise in glory!

I read it in the Orlando Sentinel, on page 10 of the front section of today's paper, part of an article entitled, "Will census show Latino boom?"

And people wonder why I don't trust the mainstream media. Part of me still retains a small hope that professional news organizations—like our local newspaper—have more of a chance of getting the news right than the average Internet source, but they keep taxing my credulity. Here's the latest.

[E]xperts say the typical hurdles for an accurate census have been aggravated by a controversial question proposed by the Trump administration—"Is this person a citizen of the United States?"—that some fear will dissuade non-citizens from participating.

"The biggest barrier is one that the Trump administration has created," [attorney Tom] Wolf said. "This would mark the first time in American history that the census would try to ascertain the citizenship status of the entire country."

The emphasis is mine. Tom Wolf is "an attorney who specializes in the census and redistricting at the Brennan Center for Justice in New York." Specializes in the census? I suppose I could give him the benefit of the doubt and allow that perhaps he was wildly misquoted—but I'm skeptical.

From my genealogical work, I knew he was wrong: citizenship questions had been asked before. What I didn't know until I looked it up again was just how wrong he was. Check out the following census years:

1870

- Is the person a male citizen of the United States of 21 years or upwards?

1890

- Is the person naturalized?

- Has the person taken naturalization papers out?

1900

- What year did the person immigrate to the United States?

- How many years has the person been in the United States?

- Is the person naturalized?

1910

- Year of immigration to the United States

- Is the person naturalized or an alien?

1920

- Year of immigration to the United States

- Is the person naturalized or alien?

- If naturalized, what was the year of naturalization?

1930

- Year of immigration into the United States

- Is the person naturalized or an alien?

1940

- If foreign born, is the person a citizen?

1950

- If foreign born, is the person naturalized?

1970

From 1970 on, the census stopped asking all the questions of everyone—only a small percentage of households received the long form with the interesting questions. Speaking as a genealogist, that was a very big mistake.

- For persons born in a foreign country—Is the person naturalized?

- When did the person come to the United States to stay?

1980

- Is this person a naturalized citizen of the United States?

- When did this person come the United States to stay?

1990

- Is this person a citizen of the United States?

- If this person was not born in the United States, when did this person come to the United States to stay?

2000

- Is this person a citizen of the United States?

2010

In 2010 the short census form had a mere 10 questions, and the long form was replaced by the annual American Community Survey. The ACS asked questions about citizenship.

So, Mr. Wolf is correct if he only considers the censuses taken from 1960 onward. But he ignores eight censuses in which the country did, indeed, "try to ascertain the citizenship status of the entire country." The proposed question is hardly something new.

The U. S. Federal Census has often asked nosy and sometimes peculiar questions, such as

- Is the person deaf and dumb, blind, insane, or idiotic?

- Can the person read?

- Was, on the day of the enumerator's visit, the person sick or disabled so as to be unable to attend to ordinary business or duties? If so, what was the sickness or disability?

- For mothers, how many children has the person had? and How many of those children are living?

- Is the person's home owned or rented? If it is owned, is the person's home owned free or mortgaged?

- Is the person a survivor of the Union or Confederate Army or Navy?

- Person's father's mother tongue

- Is the person an employer, a salary or wage worker, or working on his own account?

- Does the household own a radio?

- Number of weeks worked in the year

- What is the highest grade this person has attended in school?

- How did this person get to work last week?

There was a time in my life when I was disgusted with the census for asking such personal questions. But now I see them as an invaluable glimpse into the world of my ancestors—and our country's history. I grieve that the names of all household members don't show up until 1850, and that most of the country has been excluded from the interesting questions since 1970.

I don't see how the Sentinel has a leg to stand on with its statement that the census has never before asked the citizenship of all the country's inhabitants. Why I continue to believe so much of what I read boggles my mind. Maybe for the same reason I agree to all those End User License Agreements.

It took a long time for me to dip my toes into the DNA testing waters, being both an avid genealogist and a very private person. But just as giving birth changed my relationship to modesty, starting a blog changed my relationship to privacy. I'm still both modest and private, but not in the same way. The biggest obstacle to DNA testing was knowing I was dragging my family along. As recent events have shown, criminal behavior (and other indiscretions) can be found out by DNA through relatives' information available on genealogy websites.

But I discovered long ago that privacy as we knew it is dead. I remember working with a family researcher who was writing a book on one side of our family. At one time, I would have refused to contribute any information, but had since been helped so much in my research by a book on the Wightman Family that I wanted to help others the same way. The Wightman book, incidentally, has information on me and our family that was contributed without my knowledge or consent. At the time I was not happy, but I got over that and now appreciate it. Except for where the data is wrong....

The point, however, is that while such direct contributions help researchers, they're not all that necessary. When one of my family members declined to contribute his family's information to the project I was helping with, the researcher understood his reluctance—but he added, "Let me show you the information I've already obtained from public sources." He already had just about everything he could use. As Illya Kuryakin Dr. Mallard said on NCIS last night, The Internet will be the death of us. Or at least of privacy.

In light of all this, Porter and I each decided to submit a sample to AncestryDNA.com, and eagerly awaited the results. Later we uploaded the DNA data to MyHeritage.com, and eventually gave another sample to 23andMe.com—the latter for both the ancestry and the health screening.

This post is not for a detailed analysis of the results, but an overall impression of the value of the DNA testing. First, from the point of view of genealogy.

For us, the Ancestry.com screening was the most useful. This is for two reasons.

- They have the largest database from which to work, and that is what makes the testing useful—comparing your DNA to that of other populations. For this reason it is also most useful for those of European background, because of the large numbers of that population who have participated. The testing services are working to improve the experience for under-represented populations, but for now the data is not so robust.

- I have uploaded our family tree, with its nearly 15,000 individuals, to Ancestry.com, and that's largely what makes their DNA service helpful for genealogy. This gives context to our DNA matches, and I've already confirmed known relatives while learning of several more. My tree is at the moment private on Ancestry, which means people have to ask me about the information, which is a good way to get to meet them. Someday I will make it, or at least a version of it, public, but the tree itself isn't ready for that exposure yet.

No doubt MyHeritage would be more useful if I put a tree up there as well, but that's on the "Someday/Maybe" list. I only uploaded our data because at the time they gave free access to their resources if you did. So far they've only found us "third-to-fifth cousins"—tons of them—which is not of much use without trees to compare, and most people seem to have no trees or very small ones. Third cousins share a great-great-grandfather, so it requires a significant amount of family history knowledge to make the connection.

23andMe is in the same situation as far as genealogy goes. So far nothing found even as close as second cousin (sharing a great-grandfather).

How has this helped my genealogy research? Well, through Ancestry.com I've connected with a few previously unknown cousins, a couple close enough to be useful in sharing information. Even the ones that are more distant have been useful in providing some confirmation of my research. Overall I'm glad I took the plunge, if only for this reason. It also has a lot of potential for more and better information as time goes on. One important caveat: There is a lot of error in online family trees. Even with DNA support, this information is best taken as inspiration for further research, and for mutual sharing of data sources.

Now for what most people want out of DNA testing: heritage and ethnicity information. This is an estimate only, and each company has its own data and algorithm for making its "best guess." Sometime after we had our samples analyzed, Ancestry.com upgraded their system and re-analyzed our data. The results were not terribly much different from the first attempt, though probably more accurate.

The analysis from MyHeritage was closer to Ancestry's original analysis. That from 23andMe was different from any of the others, though quite similar overall.

My impression? The DNA analysis is very good as an overall picture, not so good on the details. For example, Porter's great-grandparents came to the United States from Sweden, and it is well known where they lived before emigrating. In fact, when his dad visited Sweden, he was told he looks just like people who live in that area. Thus when his father's AncestryDNA analysis came back showing his largest ethnicity to be Norwegian, we were taken aback. However, the area he's from may be called Sweden, but it's right on the border with Norway. One can definitely say from his DNA that he is of Scandinavian origin, but that he is specifically Swedish comes from genealogy. One must also remember that the smaller percentages are suspect: of the three analyses, 23andMe was the only one that gave me "broadly East Asian and Native American" ancestry, and that was at just 0.1%, so highly doubtful.

Finally, there's the analysis of genetic health data. This comes primarily from 23andMe, though we also paid an extra $10 post facto for Ancestry's "Traits" screening. I've written about the latter experience before. 23andMe analyzes many more traits than Ancestry's small sample, from "Leigh Syndrome, French Canadian Type" carrier status, to estimated risk for late-onset Alzheimer's Disease, to Lactose Intolerance, to Asparagus Odor Detection.

My thoughts? Interesting, but not quite ready for prime time. Where I have independent data it sometimes confirms, sometimes contradicts the DNA reports. Ancestry says I likely have a "unibrow" but 23andMe says the opposite. Both of them say I probably hate cilantro, and I love it. And so on. So I'm taking the rest of what they say with a few grains of salt. I'm sure there's something to it, and that the data will get better with time, but for now it is more entertainment than useful information. Actually, I take that back: Just as DNA ancestry data is useful as a starting point for further research, the discovery of certain traits might be useful for suggesting further, medical, genetic testing.

There's a lot more to DNA analysis for the serious genealogy researcher to investigate, such as sites that will take your data and give you tools to learn much more about which particular genes you and a DNA match share. I'm not there yet; I have too much to do with my regular research to explore that path further. But it, and my data, are there when I'm ready.

Am I glad I decided to "spit in the tube"? Absolutely; I'd do it again and may later go further with it. I'm very grateful to family members who have taken the plunge as well, because that provides a look at the puzzle from more angles. But it's always important not to expect too much. It's never as simple as trading your kilt for lederhosen, as the Ancestry.com ad blithely shows. Plus there's a risk of finding out things you don't want to know—about family or about health. It's a very personal decision and I understand those who are reluctant to take the risk.