With the engagement of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle making the news, and my old friend Gary Boyd Roberts* and the New England Historic Genealogical Society providing temptation in the way of an article and a handy genealogy chart, I decided to spend some time trying to link their data with my own. And indeed, I could. As it turns out, Meghan Markle is my 23rd cousin, once removed, with common ancestors King Edward I of England (Longshanks) and Eleanor of Castile, through American immigrant ancestor Robert Abell. Through the same common ancestors (but a mostly different line on his part, of course), I am also Prince Harry's 23rd cousin, once removed. Yes, this means that Prince Charles is my 23rd cousin, and Queen Elizabeth II is my 22nd cousin, once removed. Who knew?

Similarly, Porter is 23rd cousin three times removed to both of them, with common ancestor King John (Lackland) of England and his mistress, Clemence, through the American immigrant ancestor Thomas Yale.

Not that I can claim anything special in all this. Millions of Americans are cousins to the new royal couple. They just don't know it—as I did not until now. But I love puzzles, and have finally learned—no thanks at all to my school experiences—that history is fascinating.

It's all too easy, when one's eyes and mind are blurred by immersion in a sea of birth, death, and marriage data (or worse, the lack thereof), to forget that our ancestors were real people who laughed and cried and joked, just as we do. Then, every once in a while, you come upon something that wakes you up, such as a comment from Dr. Lewis Newton Wood, my great-great-great grandfather.

Lewis Newton Wood, son of David and Mercia (Davis) Wood, was born in southern New Jersey, on January 12, 1799. In 1821 he married Naomi Dunn Davis, born September 8, 1800, the daughter of David and Naomi (Dunn) Davis. Their first child, my great-great grandfather, was born in New Jersey, but the other seven of their children were born after they moved to upstate New York, near Syracuse. There, Lewis taught school, and in 1836 he graduated from the newly-formed Geneva Medical College, then part of Geneva College, which is now Hobart and William Smith. The medical school itself is now SUNY Upstate University. Perhaps the most famous graduate of the Geneval Medical College is Elizabeth Blackwell, Class of 1849, America's first licensed female physician.

Lewis moved to Chicago to practice medicine, and his family followed a year later, after which they migrated some 90 miles northwest to become some of the earliest settlers of Walsorth, Wisconsin. Eighteen years later they moved to their final destination, about 100 miles further north and west, to Baraboo, Wisconsin. There, Lewis died in 1868, and Naomi in 1883; they are buried in the Walnut Hill Cemetery in Baraboo. My great-great grandfather, incidentally, continued the family's northward and westward migration, moving first to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and finally to the west coast of Washington.

Lewis was not only a teacher, doctor, pioneer, and probably farmer (given that he lived on 360 acres in Big Foot Prairie), but also an amateur geologist who made notable scientific contributions, one of the founders of a school of higher education for girls in Baraboo, and a member of the Wisconsin state legislature. He even has his own Wikipedia entry, a link I incude with the standard Wikipedia cautionary tale about not believing everything you read, since some of the facts about him are wrong.

After that historical and genealogical excursion, I arrive at the reason for this post, the saying of Lewis Newton Wood's that struck my funny bone. It's taken from Gilbert Cope's Genealogy of the Sharpless Family Descended from John and Jane Sharples, Settlers Near Chester, Pennsylvania, 1682.

All my progenitors were Baptists of the Orthodox belief, i.e. Calvinists; and that is my own religious belief, except with the Calvinism pretty much left out.

Which may explain why this Baptist's funeral was held in a Methodist church. I know, it actually makes sense when you dig into the history of the Baptist Church, but still....

I like an ancestor with a sense of humor.

Another genealogical puzzle with my research and conclusions.

The Problem of Jonathan Stoddard Wightman’s Wife

The Puzzle

There are two men named Jonathan Stoddard Wightman in my family tree. One, who was born May 22, 1830, in Bristol, Hartford County, Connecticut, and died on September 9, 1893, in South Meriden, New Haven County, Connecticut. On April 26, 1855, he married Olive Fidelia Davis, born April 26, 1833 in Meriden, died March 13, 1903, in Southington, Hartford County, Connecticut, daughter of Zina and Amanda (Stevens) Davis. There’s work I could still do on this family, but I’m happy with what I have.

His parents were Elbridge M. Wightman, born about 1800 in Southington, died April 14, 1875 in Bristol. On June 17, 1829, in Bristol, he married Ursula Perkins, born 1812 in Southington, died August 7, 1889 in Bristol. She was the daughter of Elijah Mark Perkins and Polly Yale, who has an interesting line of her own.

The problem comes with Elbridge Wightman’s father, the first Jonathan Stoddard. He was born July 17, 1765 in Groton, New London County, Connecticut, and died April 18, 1816 in Southington. His second wife was Hannah Williams, who had married, first, Dr. John Hart of Southington.

His first wife, the mother of all but one of his children, is the unknown.

The Sources

- Wade C. Wightman, The Wightman Ancestry, including "George Wightman of Quidnessett, RI (1632 - 1721/2) and Descendants" by Mary Ross Whitman (Chelsea, MI: Bookcrafters, 1994), pp. 96-97.

- The American Genealogist, New Haven, Connecticut: D. L. Jacobus, 1937-. (Online database. AmericanAncestors.org. New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2009 - .), v. 25, Donald Lines Jacobus, "The ‘Other’ Gilletts” pp. 174-191.

- Bertha Bortle Beal Aldridge, Gillet, Gillett, Gillette families, including some of the descendants of the immigrants Jonathan Gillet and Nathan Gillet...also of the descendants of Barton Ezra Gillet, 1800-1955 (Victor, N.Y:, 1955), p. 25.

- Esther Gillett Latham, Genealogical data concerning the families of Gillet-Gillett-Gillette : chiefly pertaining to the descendants of Jonathan Gillet... (Somerville, Massachusetts:, 1953), 70.

- Lorraine Cook White, The Barbour collection of Connecticut town vital records (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Pub. Co., 1994), Colchester 103 (Gillett), Farmington 55-56 (Gillett).

- Ancestry.com. Connecticut, Church Record Abstracts, 1630-1920 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: 2013., Southington v107 p17, Gillet.

- Ancestry.com. Connecticut, Wills and Probate Records, 1609-1999 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015., Hartford Probate Records v1-3, pp196-197 Zachariah Gillet. Also Hartford Probate Packets, pp 916-933 Zachariah Gillet, and Hartford Probate Packets, pp 81-82, Nehemiah Gillet.

- Personal conversation with genealogist Gary Boyd Roberts of the New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

- Family notes of Elinor (Wightman) (Fredrickson) Fisher, 3rd great-granddaughter of the Jonathan Stoddard Wightman in question.

The Data

From Ellie Fisher’s Notes

Jonathan Stoddard Wightman’s first wife was Patty Hillet.

From the Wightman Ancestry

He married first, Mercy (Patty) Gillet, baptized 1768, daughter, probably, of Zachariah Gillet. (No date given, but their first child was born about 1789.)

From The ‘Other Gilletts’ TAG article

Donald Lines Jacobus presents an ancestral line from William Gillett of Somerset, England, through his son Jeremiah, ending with a daughter of Zachariah Gillett and his third wife, Sarah: Mercy, born at Southington, baptized September 4, 1768.

From Gillet, Gillett, Gillette Families

Bertha Bortle Beal Aldridge presents a different ancestral line from William Gillett of Somerset, this one through his son Jonathan, ending with a daughter of Nehemiah Gillet and his second wife, Martha Storrs: Martha, no dates given.

From Genealogical Data Concerning the Families of Gillet-Gillett-Gillette

Esther Gillett Latham presents the line through Jonathan and Nehemiah m. Martha Stoors, showing daughter Martha born April 12, 1767.

From the Barbour records

Colchester: Martha, daughter of Nehemiah and Martha, born April 12, 1767.

Farmington: several of Zachariah and Sarah’s children are listed, but several are missing, including Mercy.

Southington: there are no Gillets mentioned at all.

From Connecticut Church Record Abstracts

Records the baptism, on September 4, 1768, of Mercy Gillet, daughter of Zecheriah, in Southington.

From Connecticut Wills and Probate Records

Zachariah’s will, although it names Mercy as his daughter, mentions no married name for her. The will was written in November 1789. The probate papers show that she is still unmarried in March 1791. Also that Zachariah’s wife is named as Rhoda, and in March 1791 is known as Rhonda Frisbee.

Nehemiah’s will, written in July 1807, names his daughter Martha, still single at that time.

From a conversation with Gary Boyd Roberts

He mentioned that Jonathan Stoddard Wightman’s first wife was Martha Gillet.

The Questions

What was her name?

I respect personal information in the memory and records of family members, but am inclined to conclude that “Hillet” in the Ellie Fisher notes was, somewhere along the line, a misreading of “Gillet.” That settled, all sources agree on her last name. Her first name is a different story.

Ellie Fisher names her Patty; Wightman Ancestry has Mercy (Patty). According to the published lines from William Gillett, if her father is Zachariah, her name is Mercy; if he’s Nehemiah, she’s Martha. Unfortunately, both of these lines stop with Mercy/Martha; no marriage is recorded for either of them. But I have found no other reasonable suggestions for the parentage of Jonathan Stoddard Wightman’s wife.

In favor of the Nehemiah line (Martha): “Patty” is a common nickname for Martha, but uncommon for Mercy. My admiration for Gary Boyd Roberts as a genealogist is great, and he said her name was Martha. On the other hand, it was a very short, casual conversation and the information was off the top of his head, so I don’t want to rely too much on his memory.

In favor of the Zachariah line: The only printed source that records her marriage to Jonathan Stoddard Wightman (Wightman Ancestry) calls this line “probable” and mentions no other. But the most significant factor, I believe, is that this line places her in Southington (Hartford County), where all their children were born, whereas the other line is in Colchester (New London County).

When was she born? With the Nehemiah line, I have a birthdate: April 12, 1767. For the Zachariah line, there is only a baptism date: September 4, 1768. To say “about 1768” hedges my bets nicely.

When were Patty Gillet and Jonathan Stoddard Wightman married? Wightman Ancestry gives the birth of their first child as “about 1789” based on a death date of July 13, 1864 and an age at death of 75. This is consistent with census and gravestone data. Yet Zachariah’s probate records show Mercy as unmarried in March of 1791. (She signs her name “Mercy Gillet” and there is no mention of a husband.) Even if she was married that year, the timing is a little uncomfortable for the Zachariah line.

But the Nehemiah line is worse: Martha was still single when her father wrote his will in 1807, by which time all nine of J. S. Wightman’s children had been born.

Why didn’t these girls get married before their fathers wrote their wills? It would have made things so much clearer. But I think, after all, it is clear enough. The evidence of the wills, combined with the evidence of the location convinces me that Patty Gillet, wife of Jonathan Stoddard Wightman, was Mercy Gillet, daughter of Zachariah and Sarah Gillet of Southington.

One more question: What about Zachariah Gillet’s wives? Donald Lines Jacobus gives him three, the first two totally unknown, and the third known only as Sarah. Bizarrely, however, he claims that Zachariah’s will names his wife Sarah, whereas the wife in both copies I found of the will seems clearly to be “Rhoda.” Jacobus gives no death date for Sarah, but it’s a good assumption that she predeceased Zachariah, who married a fourth time. After Zachariah's death, Rhoda married someone named Frisbee.

I found a will for a Sarah Gillet, dated and probated in 1776, witnessed by Zachariah Gillet and Elizabeth Gillet. In this will, Sarah Gillet leaves everything she has to “my Nephu Sarah Andrus wife to Ichabod Andrus.” Sarah Gillet, daughter of Zachariah and his first wife, did marry Ichabod Andrus (Andrews). At first I thought this might be the will of Sarah, Zachariah’s wife. But Donald Lines Jacobus says it’s the will of Sarah, Zachariah's sister, daughter of Abner Gillet. That makes more sense, though I'm still confused by “nephu."

The Conclusions

Pending new evidence to confirm or debunk my conclusions, this is what I believe:

Jonathan Stoddard Wightman was born July 17, 1765 in Groton, New London County, Connecticut, and died April 18, 1816 in Southington, Hartford County, Connecticut. He married (1) Mercy (Patty) Gillet, born about 1768 in Southington, daughter of Zachariah and Sarah (surname unknown) Gillet. Jonathan married (2) Hannah Williams, widow of Dr. John Hart of Southington.

The ancestry of Zachariah Gillet, taken from “The ‘Other' Gillets” by Donald Lines Jacobus, published in The American Genealogist (see above), is, in an abbreviated form, as follows:

- The Reverend William Gillett, Rector of Chaffcombe, County Somerset, England.

- Jeremiah Gillett, born in England, emigrated to New England, lived in Wethersfield, Connecticut, and fought in the Pequot War of 1636-1638. Later he returned to England, but because of his service was granted land in Simsbury, most likely tended by his brother, Nathan of Simsbury until Jeremiah, Jr. arrived.

- Sergeant Jeremiah Gillett of Simsbury, Connecticut. He was probably born in England, about 1650, and he died in Simsbury on March 24, 1707/8.

- Abner Gillet, born perhaps 1684-88, died March 12, 1762 at Southington, Connecticut. He married, at Farmington, Connecticut, September 6, 1710, Mary Higginson, who was baptized at Farmington January 10, 1691/92 and died at Southington on February 8, 1766. She was the daughter of William and Sarah (Warner) Higginson.

- Zachariah Gillet, born at Farmington March 31, 1721, died at Southington in 1790. He married (1) at Southington, July 6, 1741, an unknown woman, (2) at Southington, April 3, 1750, another unknown woman who died September 1757, and (3) Sarah (surname unknown). According to my own conclusions, based on probate evidence, he also married (4) Rhoda (surname unknown) who later married someone named Frisbee.

UPDATED: See the revised version here.

Genealogy research consumes my life, albeit in fits and starts, as other projects push themselves into the forefront of my life. Lately, it has consumed every spare moment, and some not-so-spare, as I have given priority to cleaning up my database, which currently contains nearly 15,000 people. The goal is to be able to publish my database on Ancestry.com, and there are too many questionable and unsourced trees there already. If I'm going to put my data out there—and I believe I have a responsibility to do so—I want to do it as well as I can.

As I go through the process, I inevitably run into problems. The psychological process of working through them is worthy of a blog post in itself, but not now. What I will do now is begin to document here some of the work: the data, the sources, my thought processes, my conclusions. Doing so helps me think and increases my own understanding. It also gets some of the data "out there" where it may be of interest to others researching the same people. The posts will often be very long, and of little or no interest to most of my readers. Feel free to skim or skip them altogether! I post them for those random visitors who end up here through a Google search on a name of interest, because I have been helped in my own work by just such a process.To begin:

The Problem of David Wood

The Puzzle

I’m pretty happy with the line of my family tree that goes up (on my father’s side) to David Wood, born May 1, 1778 in Stow Creek Township, Cumberland County, New Jersey, died there in 1828, probably. He married, April 11, 1798, Mercia Davis, born July 15, 1777 in Cumberland County, died there December 1, 1823, daughter of Isaac and Mary Ann (David) Davis. I’m good with that.

I also have an okay line up from David’s grandfather, Jonathan Wood, who died in Cohansey, Salem County, New Jersey in 1727, and was married to Mary Ayers. This goes back to a John Wood who died at Portsmouth, Rhode Island in 1655. Details are sparse, but at least the line is there.

The problem, as is often the case, is in the middle.

I know that David Wood, Jr.’s father was David Wood, Sr., son of Jonathan and Mary (Ayers) Wood. But David Wood, Sr. had three known wives, and what details are known have few dates associated with them. I’m convinced that David Jr.’s mother was named Prudence Bowen; I haven’t found her parents, though supposedly she was the sister of David and Jonathan Bowen, of Bowentown, Cumberland County, New Jersey. Am I certain enough to put time into following the Bowen line? Probably, though not now.

I’m not at all certain my logic will convince anyone else, but I’m equally uncertain I’ll get any better documentation. As one of my correspondents understated, "New Jersey records are very hard to find." I’ve been spoiled by working mostly with early New England ancestors. Say what you want about the Puritans, those folks knew how to keep records. And when something like engaging in illicit sex or selling liquor to Indians lands you in the court dockets, that’s a bad thing for you but a great thing for future genealogists.

The Sources

Vital records (birth, marriage, death), church records, wills, and probate records are wonderful genealogical resources, since they are usually contemporaneous with the events they describe.That’s not to say they’re without error, but they are generally considered reliable.New Jersey was not as good as New England at keeping these early records, but I found some.

- Ancestry.com. New Jersey, Marriage Records, 1683-1802 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011, v. 22 p. 52 Prudence Bowen and Simeon Roberts, and v. 22 p. 335 Prudence Roberts and David Wood. (Original data: New Jersey State Archives. New Jersey, Published Archives Series, First Series. Trenton, New Jersey: John L Murphy Publishing Company.)

- "New Jersey, Deaths, 1670-1988," database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2SZ-1FPR : 18 October 2017), Anley McWood, May 1853; citing Roadstown, Cumberland, New Jersey, United States, Division of Archives and Record Management, New Jersey Department of State, Trenton.; FHL microfilm 493,711.

- Ancestry.com. New Jersey, Abstract of Wills, 1670-1817 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011, v. 9, Abstracts of Wills, pp. 50-51 Jonathan Bowen, and pp. 419-420, David Wood Sr. (Original data: New Jersey State Archives. New Jersey, Published Archives Series, First Series. Trenton, New Jersey: John L Murphy Publishing Company.)

Although published genealogies are far from primary sources, they are usually—according to my contact at the New England Historic Genealogical Society—reasonably reliable on the American side of the Atlantic Ocean, even though many fictitious across-the-pond connections abound.Therefore I’m designating these sources as credible, if not as good as primary sources.

- Bruce W. David, The David Family Scrapbook: Genealogy of Owen David, Volume 5 (3223 Ormond Road, Cleveland Heights, Ohio: Bruce W. David, Volume 5, 1964), pp. 315-316.

- Gilbert Cope, Genealogy of the Sharpless Family Descended from John and Jane Sharples, Settlers Near Chester, Pennsylvania, 1682: Together with some account of The English Ancestry of the Family, including the results of researches by Henry Fishwick, F.H.S., and the late Joseph Lemuel Chester, LL.D.; and a full report of the bi-centennial reunion of 1882 (Philadelphia: For the family, under the auspices of the Bicentennial committee, 1887), p. 545.

- Dorothy Wood Ewers, Descendants of John Wood: A Mariner who died in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, in 1655 (Colorado Springs, Colorado: Ewers, 1978), pp. 54-56.

Family tree date abounds online, and its credibility is exceedingly variable.Some online trees are maintained by excellent, sometimes professional, researchers.Some contain undocumented but accurate personal memories.And there are also many, many trees that have merely copied someone else’s data that is entirely wrong—a widespread propagation of error.Unless something about the source convinces me otherwise, I consider this data suspect, but it can still be a source of ideas and hints.

- Family tree data from Ancestry.com, FamilySearch.org, and other Internet sites.

The Data

From the David Family Scrapbook

David Wood Jr. was born May 1, 1778, the son of David Wood, Sr. and Elizabeth Russell. (I believe the designation of Elizabeth as his mother to be erroneous.)

From the Sharpless Genealogy

David Wood (Sr.) died about 1798, “aged over 70.” His wives and children:

- Lucy Lennox, no issue.

- Prudence, sister of David and Jonathan Bowen of Bowentown, Cumberland County, New Jersey. Children:

- David Jr., born May 1, 1778 in Stow Creek, Cumberland County, New Jersey; married April 11, 1798, Mercia Davis, daughter of Isaac and Mary Anna Davis.

- Auley McCalla

- Sarah

- Prudence

- Elizabeth Russell. Children:

- John

- Lucy

- Richard

From Descendants of John Wood

David Wood, Sr. was born 1721, died 1794 in Stow Creek, New Jersey, “over 70.” His will was written March 10, 1794, proved January 18, 1798. Two scenarios are presented for his wives and children, from different correspondents:

- Lucy Lennox, no children.

- Prudence Bowen, married 1777. Children:

- David

- Auley

- Sarah

- Prudence

- Elizabeth Russell, married in 1786. Children:

- John

- Lucy

- Elizabeth

- Richard

Alternatively, the following children, not assigned to mothers, and in no particular order (clearly taken from David’s will, see below):

- Sarah

- Prudence

- Lucy

- Obadiah

- James

- Phebe

- Lydia

- Aulay McAuliff (McCalfa, McCalla)

- David

- John

From New Jersey Marriage Records

I find nothing for a Prudence Bowen marrying a David Wood, but there are these records of marriage licenses issued:

- Prudence Bowen of New Town and Simon Roberts of Philadelphia, June 14, 1762.

- Prudence Roberts of Cumberland and David Wood of Salem, July 9, 1777.

It’s likely that these represent the first and second marriages of the same person, especially since that agrees with the 1777 date in Descendants of John Wood.

From New Jersey Deaths, 1670-1988

Anley McWood (Auley McCalla Wood). Death, May 1853, Roadstown, Cumberland, New Jersey. Residence Stoe Creek, Cumberland, New Jersey. Male, age 69, occupation farmer. Estimated birth year 1784. Birthplace Stoe Creek, Cumberland, New Jersey. Father David Wood, mother Prudence Wood.

From New Jersey Abstract of Wills

- Will of Jonathan Bowen, February 21, 1804. He was likely the Jonathan, brother of David of Bowentown, mentioned in Sharpless above, hence brother to David Wood’s wife Prudence. Among many other bequests, he leaves a share of his household goods to “my niece, Mary Roberts,” strengthening the notion that this Prudence was once married to Simeon Roberts.

- Will of David Wood, Sr. of Stow Creek Township, Cumberland County, March 10, 1794.

Wife, Elizabeth, 1/3 of personal. Son, Obadiah, £50. Daughters, Sarah, Prudence, and Lucy Wood, son, John, and if wife should be pregnant, the said child; the remainder of personal, divided between them, when of age. Son, John, to be put to a trade, when 14. To heirs of son James, 5 shillings. To heirs of daughter, Phebe, 5 shillings. To heirs of daughter Lydia, 5 shillings. Son, David, 4 acres of woodland bounded by land of David Gilman, Dorcas Bennett to John Dare’s land; also 10 acres of marsh in Stathem’s neck. Son, Aulay McCalla Wood, remainder of home plantation with buildings; also remainder of swamp at Stathem’s neck; should said sons, David or Aulay McCalla, die before of age, said property to the survivor of them. Executor—Azariah Moore, Esq. Witnesses—George Burgin, Mary More and Martha More. Proved Jan. 18, 1798.

January 10, 1798. Inventory, £221.9; made by Joel Fithian and David Gilman.

January 18, 1798. Azariah Moore, having renounced the Executorship. Adm’r—C.T.A.—Jonathan Bowen. Fellowbondsman—Benjamin Dare.

From assorted online family tree data

- David Wood Sr. was born 1721 or 1740, died 1798, married Lucy Lennox 1760.

- Lucy Lennox was born 1742, died 1773. Her children were Obadiah (born 1760), James (born 1760), Phebe (born 1762), Richard (born 1768).

- Prudence Bowen was born in 1754, died in 1778, married David Wood 1774. Her children were Prudence (born 1776), Sarah S. (born 1776 or 1777 or 1779), Auley (born 1775).

- Elizabeth Russell was born in 1755, died in 1797, married David wood in 1779. Her children were Prudence (born 1776 died 1777), Lydia (born 1778), Elizabeth (born 1779), David (born 1778), Lucy (born 1767), John (born 1780).

- Simeon Roberts, born about 1735 in Philadelphia, died about 1766 (probate) in Philadelphia, married Prudence Bowen (born 1740 in Newton, Sussex, New Jersey) June 14, 1762 in New Jersey. Their child: John (born about 1780).

And more. The data is inconsistent and confusing as well as unreliable.

The Questions

So what can I make of all this?

First of all, let’s deal with the name of one of David’s sons: Auley McCalla Wood. By his death record, Auley McCalla is definitely established as the child of David and Prudence Wood. But what kind of a name is that for a child? First of all, despite the alternate spellings given in Descendants of John Wood, Auley (or Aulay) McCalla is probably correct. The name shows up more than once in New Jersey; David Wood’s child was no doubt named after a friend, or someone his parents respected.

The will is the most interesting document, and I’m sorry I only have an abstract to work with. Struggling with hand-written wills is hard on both the eyes and the brain, but can give insights a summary misses. Still, the abstract is something to work with.

Of the twelve children mentioned in the combined sources—David, Auley McCalla, Sarah, Prudence, John, Lucy, Richard, Elizabeth, Obadiah, James, Phebe, and Lydia—two are missing from the will. For that time period, it’s not unlikely that Richard and Elizabeth had died before the will was made, so there’s no need to assume they’re extraneous additions to the records.

That Elizabeth Russell was David’s third wife is supported by the mention of Elizabeth in his will. Next comes Obadiah. It’s not specified that he is the firstborn, but that’s customary, and as he’s bequeathed his £50 outright, he must have been at least 21 years old in 1794, unlike Sarah, Prudence, Lucy, John, David, and Auley McCalla, who are clearly not yet of age. John is something less than 14 in 1794, making him born after 1780.

The five-shilling bequests to the heirs of children James, Phebe, and Lydia are another puzzle. Why the heirs? Are James, Phebe, and Lydia older, married … and dead? Or did David just want to leave something directly to his grandchildren (sadly, unnamed)? In any case these three children seem to be married and on their own. I’m trying to be grateful to David for actually leaving a will, since many did not, instead of wanting to shake him by the shoulders and demand to know why he didn’t include surnames for most of the people he mentions.

But who are these children?

One scenario is that Obadiah, James, Phebe, and Lydia are Prudence’s children from her first marriage. It’s possible, because there were 15 years between her first and second marriages, if the dates are right. But I think it more likely that they were Lucy Lennox’s children, already grown and on their own by the time their father made his will. Of course it’s possible that Lucy simply didn’t have any children; infertility is not exclusively a modern problem. But David specifically names these children as his. On the other hand, relationship naming was more fluid in the past: When a document specifies “my brother” or “my uncle,” for example, it does not necessarily mean by these terms what we do now.

One thing that speaks to these children being Prudence’s by her first husband is the naming patterns. It seems unusual for David to have at least two sons before giving one of them his own name. He did have an uncle Obadiah, as well as an uncle John. The sources of the names Lucy, Prudence, and Elizabeth are obvious, though if James, Phebe, Lydia, Richard, Sarah, or Auley McCalla are in his family tree, I don’t know about it. But I can’t find any information on children for Prudence and Simeon, nor for Lucy and David, to help solve the puzzle. I think it more likely these are Lucy’s children, but I may be wrong.

Wills often name children in order of their birth, but sometimes that order is within categories, such as all sons and then daughters. In this case, I would guess that Sarah, Prudence, Lucy, and John are listed from oldest to youngest; likewise James, Phebe, and Lydia; also that David is older than Auley McCalla, which we already know from their birthdates.

Figuring out birth order between one category and another is more of a problem. Unlike most of my sources, I place Sarah and Prudence between David and Auley McCalla because of the large gap in the latter’s birthdates, although it’s possible that Prudence was born last and her mother died in childbirth..

Although it is mostly speculation on my part, here is the scenario as I imagine it. As was customary, David’s widow received 1/3 of the personal property—as I understand it, this is pretty much everything that’s not land. It was valued at £221.9, so her share would have been £74. (Or possibly £57, if Obadiah’s £50 was deducted before the division. I’m afraid I don’t know enough about legal language when it comes to wills.) That makes Obadiah’s portion a pretty large chunk of the estate, but it was not unusual back then for the firstborn son to inherit more than his siblings.

The remainder of the personal property was to be divided amongst Sarah, Prudence, Lucy, and John, probably the youngest children. This suggests that the older children may have already received gifts of goods and property and were perhaps living on their own.

David and Auley each received land. Since Auley was given the “remainder of the home plantation with buildings,” I imagine the older sons (probably Obadiah and James) had been given their shares of the land already. Why was John to be “put to a trade” (I assume apprenticed) when 14? Perhaps the land suitable for farming had already been apportioned. Maybe John didn’t want to be a farmer, and his father supported that preference, although he seems to have been too young for that to be likely.

Why were the heirs of James, Phebe, and Lydia given five shillings? Such an amount was not insignificant, but at 20 shillings to the pound, barely a drop in the estate bucket. Was it meant to be just a token for small children from Grandpa? If there were bad relations in the family and he wanted to insult them, I imagine he would have done it for even less money.

Was David Wood, Sr. really born in 1721? It seems a reasonable approximation, if it is true that he was “over 70” when he died, which was somewhere in the range 1794-1798. That makes him apparently much older than his wives, though I don't have documented birth dates for any of them. I've also seen an unsourced birth year of 1740 often suggested for David Sr. But it's not impossible that he really was that old—one of my own great-grandfathers was 59 before producing any children. Absent any compelling evidence to the contrary, I’ll stick with the earlier date, though since I think it’s a guess from the uncertain death date, I’d put it more at about 1725.

The Conclusions

Always being ready to scrap speculations in light of new data, this is what I now believe about David Wood, Sr.

David Wood, Sr. was born about 1725, probably in Salem County, New Jersey. (Cumberland County was formed in 1748 from the west side of Salem County.) He died between March 10, 1794 and January 18, 1798, in Stow Creek Township, Cumberland County, New Jersey. David married three times.

His first wife was Lucy Lennox, who died before 1777, and by whom he possibly had four children. These may, instead, have been the children of David’s second wife and her first husband.

- Obadiah

- James

- Phebe

- Lydia

He married, second, about July 9, 1777, Prudence Bowen, the sister of David and Jonathan Bowen of Bowentown, Cumberland County, New Jersey. She had married, first, about 14 July 1762, Simeon Roberts of Philadelphia. Obadiah, James, Phebe, and Lydia listed above may have been their children. Prudence died before 1786.

David Wood and Prudence Bowen had, probably, the following children (order uncertain):

- David Wood, Jr., born May 1, 1778, died in 1828. He married, April 11, 1798, Mercia Davis, born July 15, 1777 in Cumberland County, New Jersey, and died there December 1, 1823, daughter of Isaac and Mary Ann (David) Davis.

- Sarah S.

- Prudence

- Auley McCalla, born about 1784, died May 1853, Roadstown, Cumberland County, New Jersey. (Living in Stow Creek, Cumberland County, New Jersey.)

David married, third, in 1786, Elizabeth Russell. (This may be a married name, from a previous marriage.) Their children (order uncertain) were probably

- Lucy

- John

- Elizabeth, died probably before 1794

- Richard, died probably before 1794

The ancestry of David Wood, Sr. taken from Descendants of John Wood, is, in an abbreviated form, as follows:

- John Wood, died 1655 in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, married an unknown wife.

- John Wood, born 1620, died August 26, 1704 in Little Compton, Rhode Island, married Anna, surname unknown.

- Jonathan Wood, born August 26, 1658 in Springfield, Massachusetts, died 1715, married, by 1692, Mercy Banbury.

- Jonathan Wood, died 1727 in Cohansey, Salem County, New Jersey, married Mary Ayers.

- David Wood, Sr., as above.

The Stranger in My Genes by Bill Griffeth (New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2016)

The Stranger in My Genes by Bill Griffeth (New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2016)

The New England Historic Genealogical Society has been pushing its new book for quite a while, and I've mostly been ignoring it. I love the NEGHS, especially its treasure-filled library in Boston. But I mostly—perhaps wrongly—associate them with dusty old tomes, the value of which lies in the bits and pieces of genealogical information that can be gleaned from them. The Stranger in My Genes is NOT that kind of book. The NEHGS very wisely published the first chapter in their American Ancestors magazine, and I was immediately hooked.

The book I was in the middle of reading (okay, barely started) is H. D. Smyth's Atomic Energy for Military Purposes. It was a gift for my father from his parents on his 24th birthday, and currently sits on my bookshelves with his other books on the immediate post-Hiroshima period. It is also nearly 300 pages of dense technical writing, so when The Stranger in My Genes became available at our local library (I had requested that they add it to their collection), it's small wonder I jumped at the diversion.

Part genealogy, part mystery, and part cautionary tale, this soul-searching human-interest story is also beautifully-crafted. What's not to like? Both Porter and I read it in a day. That's not to say it's short or simple; we just couldn't put it down.

I won't say much about the story itself to avoid spoiling the mystery. Author Bill Griffeth, an amateur genealogist, received a big surprise when comparing his DNA test results with his cousin's: they weren't related. Where that led is the subject of his book, and illustrates well the risks and benefits of genetic testing.

I don't even know who George Friedman is, but I've read a number of his essays recently, and I'm hooked. From November 7, The European Diaspora touched a nerve for me that has been aching since elementary school. You see, my ancestors were all early immigrants to this country, and in my school that was not respected. If your ancestors came to America recently enough that your parents or grandparents were immigrants, that was cool. If they came here really long ago, i.e. if you were of American Indian descent, that was the coolest of all. But in between? You were white-bread, plain vanilla, WASP-ish. Definitely uncool. I used to joke that I was considering becoming a Catholic, as that was the only part of White Anglo-Saxon Protestant I had the power to change.

For reasons I still don't know, my parents never shared much about my family heritage and resented the homework assignments that asked about it. The message I heard was simply that we were all Americans, and that was what was important. Did my mother grow up hearing her grandmother talk about being a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and had she found that boastful, or boring? Were they aware of some anti-immigrant sentiment and did they want to keep it far away from me? I have no idea. But of course I interpreted the silence as meaning there was something negative or shameful about my ancestry. And being ashamed, I was foolish and never talked with them about the atmosphere at school.

It's really not any better now. We live in a time when "dead white [European] males" are safely vilified, and living ones not much better off. "Black Pride" is a positive, uplifting thing; "White Pride" evokes images of the Ku Klux Klan, Adolf Hitler, Skinheads, and Deliverance.

I can't imagine why the color of one's skin should be a matter of pride for anyone, but long ago I grew tired of being ashamed of my heritage. Studying genealogy gave me a better sense of history than school ever did, and assured me that my family tree is as filled with heroes and rogues, the persecuted and the persecutors, those who were well-off and those who were desperately poor, as anyone's—even if it did reveal a still more solid base of white, British Isles/northern-European, early immigrants.

George Friedman is kinder than most to my family heritage. We, too, come from courageous survivors, refugees who were desperate enough to leave everything in search of hope. Where we have travelled, we have done terrible evil and brought immense good. But mostly we have simply been human families. If our stories are a little older than those of some immigrants, and newer than others, they aren't any less important.

When I come to this part of the world [Australia/New Zealand], I am always struck by a concept we never hear about: the European diaspora. The various peoples of Europe have collectively constituted a vast and ongoing diaspora. We speak of the Jewish, Armenian or Chinese diaspora. But somehow we never think of Europe as scattering its deeply divided peoples throughout the world.

There is a difference between imperial conquest and diaspora. Imperial conquest is carried out by governments and the elites. They do it for power, money and strategic advantage. The rest of us, who have moved from one country to another, are part of a diaspora. We hope to find a better life, some food to eat, a house to live in, a policeman who will not beat us. Thus, the great European conquest of the world had two sides. One was the movement of the geopolitical plates of the world. The other was the individual acts of desperation.

The diaspora was not peaceful. Europe’s wars shaped the places Europeans sought refuge. And the diaspora displaced, subordinated and killed those who were there before, much as the Zulus, the Comanche and the Aztecs did when they arrived. The settlement of the diaspora involved brutality, as do many consequential human acts.

It is odd ... that many think the settlement of the [European] diaspora is unjust because, in the process, others were displaced. But it is simply human, and like all human things, it is both just and unjust.

The European diaspora included migrants from all of Europe’s countries. There are vast areas where Spanish and Portuguese are spoken, and other regions where people converse in French or Dutch. But I will assert that the English-speaking regions have had the largest effect on the world. This may not be a popular view, but it is true that the colonies created by the English became the places where refuge can be found now and in past centuries. Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States, received the English language, marvelous in its subtlety and dynamism. And these countries have formed a web of relations with each other that has been a driver of the global system. They are not always comfortable with each other, but they have fought together and created together. They have also welcomed the wretched refuse of Europe’s teeming shores with an ease and openness not quite matched by others.

Would I still be thrilled if genealogical research confirmed the one, long-ago possibility of a Native American ancestor? If a DNA test reveals something sub-Saharan African or Ashkenazi Jew? Absolutely. But I'm done with being embarrassed by my heritage, even if it turns out to be 100% northern European. My parents were right: we are all Americans, and that's what counts. I'd go further: we are all human beings, made in the image of God, fallen and broken, but capable of being redeemed—and that's what counts. But particulars count, too: my family, my community, my culture, my heritage—and yours, and yours, and his, and theirs. No heritage has a monopoly on shame, or pride.

As a member of the New England Historic Genealogical Society, I receive—among other benefits like admission to their fantastic library in Boston—their American Ancestors magazine. The Fall 2016 issue has an article by Bryan Sykes (author of The Seven Daughters of Eve and other books of genetic genealogy) entitled, "Deep Ancestry and the Golden Thread." The fascinating essay is actually about matrilineal genealogy, but it was the introduction that made me shake my head.

We all take the link for granted these days, but we few scientists working on the Y-chromosome in the mid-1990s...had dismissed any correlation between surnames and Y-chromosomes as highly unlikely. As geneticists, we were familiar with the high rate of non-paternity, which would have disrupted the surname/Y-chromosome association over time. [Upon investigation, however] the strength of the correlation was high enough to make it a useful tool for genealogists and showed, incidentally, that the historical rate of non-paternity in England was far lower, at around 1.3% per generation, than it is assumed to be today.

That was a surprise? Really? The mindset of the "sexual revolution" is now so entrenched and ingrained that intelligent, educated scientists are shocked to learn that most children in the past did know who their daddy was, and shared his name?

I must be missing something.

My grandparents lived in Daytona Beach all their adult lives. Both arrived in 1915; my grandfather was originally from Western Pennsylvania, and my grandmother from West Virginia. My great-grandparents, John Stansbury Barbe and Minerva (Kemp) Barbe (Minnie) were very active in Daytona Beach: She was a hotel owner and busy with all sorts of community affairs, from business to politics to schools, and he was at one point mayor of the Town of Daytona Beach (before it became a city).

My grandmother ran the hotel for a while, but by the time I knew her had retired from the business and was living in my favorite place in all of Daytona Beach: 431 North Grandview Avenue. Sadly, both the house—now a business—and the neighborhood have changed, but at least the building's still there.

What more could a child want? It was a big house with lots of places to explore, a cellar that was sometimes visited by poisonous snakes, a picnic table and my grandmother's amazing flowers in the back yard, and an outdoor shower that we sometimes shared with lizards. (Living in Florida myself now, lizards are commonplace. But they were an exotic treat for a child who lived in upstate New York and only visited every other year.)

Why the outdoor shower? Not because there were no indoor facilities, but because the house was a mere two blocks from the ocean and the incredible beach; the shower was an easy way to wash off the sand and salt from our frequent swims before entering the house. It was also an easy walk from my grandparents' home to the Bandshell and Broadwalk (not "boardwalk"). As a child I was completely oblivious to the seamier side of life in Daytona Beach, though I understand now why we were never allowed to go to the Broadwalk without an adult.

Then there were the people. My Florida relatives were different from most of the folks I knew back home, which thanks to the presence of General Electric, had a higher-than-normal population of engineers and other intellectuals. My grandfather had worked for the Post Office and retained an intense interest in collecting stamps—if only I had managed to figure out how to enjoy his enthusiasm without feeling obliged to share it! My uncle was a fisherman, and I loved it when he'd let us fish with him off the Pier. My cousins were much older than I, and therefore very cool, especially the one that could be counted on to do dangerous things like set off firecrackers in the backyard (not sure how my grandparents felt about that...), and the one who was at first a lifeguard (very high coolness factor to a young girl) and eventually worked for NASA in exotic places like Grand Turk Island and could tell us stories about the astronauts (even higher coolness factor to a young nerd).

Because of their former hotel business, my grandparents had made friends from all over who still came to visit them. They even had a maid who came occasionally to help with the housework—no one else of my acquaintance had a maid—and what's more, the maid was black, which made her even more exotic than the lizards to one who was growing up in a town where "cultural differences" meant that some of your friends' parents might have come from Italy or Poland. I wish I had been more curious as a child to hear the stories of all these different people.

My grandmother was a wonderful cook, especially when she was cooking fish that had been caught just hours earlier, and most especially if they were fish that I had caught. We hardly ever ate at restaurants—in those days few ordinary people ate out, even if their grandmothers weren't good cooks. But when we did, for special occasions, more often than not it was at a place called Kay's, at 734 Main Street. It was a "family restaurant" with what you might call ordinary American fare, though my taste buds recall their fish as anything but ordinary. And definitely on the extraordinary side was a drink they called a Tiny Tim. When I knew it, the restaurant had Dickens-era decor, and one of their specialty mixed drinks they called a "Dickens." The Tiny Tim was a non-alcoholic version of the Dickens.

We all liked the Tiny Tim so much that we had it whenever we could, and eventually I begged the bartender to give me the recipe:

- 2 packages Bartender's Lemon Mix

- 4 packages Bartender's Lime Mix

- 1 package Bartender's Coconut Mix

- 3 gallons water

- 3 quarts pineapple juice

- 1 quart orange juice

- 1/3 quart lime juice

- 2 small cans grapefruit juice

- 1/2 quart cherry juice

- grenadine for color

Unfortunately, that didn't help much, though I'm sure it was only because I didn't try hard enough to find the ingredients that were not readily available at the grocery store. It occurs to me that all my efforts were BI (Before the Internet). Maybe I should try again. Anyway, I'm putting the recipe online for anyone who wants to check it out. I'm not hurting Kay's by giving away trade secrets: sadly, the restaurant went out of business, thanks in part to the neighborhood's change from family-oriented to one that catered to bikers and other tourists.

All these memories were triggered by a lunch at the Cheesecake Factory. There, Porter ordered their Frozen Iced Mango drink: "Mango, Tropical Juices and a Hint of Coconut Blended with Ice and Swirled with Raspberry Puree." It came with a strawberry, a slice of lime, and a slice of lemon as well, which may explain why despite the different ingredient list, it tasted more like a Tiny Tim than anything I've had in years. Whatever it was, next time we visit the Cheesecake Factory (which seems to be about once a year), that's what I'm ordering to go with my Avocado Egg Rolls, which is the reason for going to TCF in the first place.

The best part of our visit to St. Louis, Missouri this year was without a doubt time spent with living relatives. Yet we also had a great time visiting several dead ones.

A member of our extended family was born in St. Louis, and has roots there going back to the mid-1800's, when her great-grandparents arrived from Ireland. Hereinafter she will be referred to as GrandmaX—not to be confused with the usual Grandma on this blog, that is, me—because it is considered bad form to use the names of living people in online genealogical work. The Catholic Archdiocese of St. Louis has a great online burial search tool, so I knew that several of GrandmaX's family members were buried there. It would be fun to see what we could find.

But first, we stopped at the Old Cathedral, the Basilica of St. Louis, King of France, formerly the Cathedral of Saint Louis. This was the first Catholic cathedral west of the Mississippi (but just barely west; it’s right on the river) and was the only Catholic church in St. Louis until 1845. When all other nearby buildings were demolished for the building of the Gateway Arch, the Old Cathedral was left standing because of its historical significance. (You can click on any photo for a closer look.)

Old Cathedral

Old Cathedral  As seen from the top of the Gateway Arch

As seen from the top of the Gateway Arch

The Cathedral may or may not have been the family’s parish church, but it must in any case have been important to them, as they were at that point a Catholic family. When the family left the Catholic Church I do not know. It might have been because of the divorce of William and Margaret (Donohue) Goodman, GrandmaX's maternal grandparents, though both of them, and also Margaret’s second husband, Joseph A. Murray, and some others of their family, are buried in the Catholic cemetery. At the present time, Catholics who are divorced and remarried without having obtained an annulment are not considered to be "members in good standing," and thus cannot participate in some aspects of church life, but they are allowed to be buried in a Catholic cemetery. I don't know if that was also true in the 19th century. (More)

Sylvester Scovil left home when his son was a baby and never returned or communicated with his family.

Sylvester Scovil’s life appears to have begun normally enough. He was born November 20, 1821, into an old and respected New England family. His father, Sylvester Scovil Sr., was a descendant of John Scovell, who had arrived in the New World, almost certainly from England, sometime before his marriage in 1666. In 1686 the family was settled in Haddam, Connecticut. Sylvester’s mother, Phoebe Burr, was from an equally old and established family.

Sylvester was the middle child of seven, three boys and four girls. All of his siblings remained near home all their lives, the most adventuresome having only strayed as far as nearby Middletown. The records indicate that Sylvester was on a similarly respectable path: He was a farmer, a teacher, and a captain in the state militia. He also held several public offices, including justice of the peace and delegate to the state Democratic convention, while he was still in his twenties.

Two of Sylvester’s first cousins, Daniel and Hezekiah Scovil, founded the D & H Scovil Manufacturing Company, famous for its hoes and other metal work, and a pillar of the Haddam area.

I became interested in Sylvester Scovil while researching the story of Phoebe’s Quilt. Phoebe L. Scovil, the owner of the quilt, was Sylvester’s sister. Two other sisters, and their mother, were signers of the quilt, as was Sylvester’s wife, three of her sisters, and her mother.

On June 7, 1854, Sylvester married Frances Louisa Bonfoey, the daughter of Benanuel Bonfoey and Eliza Burr. He was 32 years old, and she 23. Seventeen months later, on November 12, 1855, their only child, Sylvester Eugene Scovil, was born. A few months after that, Sylvester disappeared.

We know nothing of why, nor how, other than the above quotation from Homer Worthington Brainard’s A Survey of the Scovils or Scovills in England and America : Seven Hundred Years of History and Genealogy. The implication is that his departure was intentional, though Brainard offers no evidence that he did not meet with an unknown accident or foul play.

Becoming a parent changes people. Most, thankfully, take a leap forward in maturity. Some, however, cannot handle their new responsibilities. Was Sylvester one of them? Did he begin to manifest the mental illness that apparently plagued him later in life? He might even have been a homosexual who could no longer face pretending to live a normal life. Or maybe he was just plain mean and selfish. If there was another woman involved, no evidence of that has yet surfaced.

Sylvester’s family—his wife, his son, his widowed mother and his three living siblings—never knew what happened to him. He was there, and then he was not. Was he dead? Was he alive, a villain who had deserted his family when they needed him most? Or had he been, perhaps, the victim of an attack that left him with amnesia? Such things have happened.

His mother lived another 30 years not knowing her son’s fate. Frances never remarried, remaining in the shelter of her own extended family to raise her son. She died on January 12, 1897, and on her gravestone she is memorialized as “Frances L. Bonfoey, wife of Sylvester Scovil.” Fatherless Sylvester Eugene grew up in the shelter of his mother’s family, then married Eva Luella Burr and had four children. They moved to Bridgeport, but when he died age of 76 he was buried back home in Haddam.

As difficult as it must have been to be left with so many unanswered questions, was this family better off not knowing what I learned about the remainder of Sylvester’s life?

It’s almost 1400 miles between Haddam, Connecticut and Grasshopper Falls, Kansas (now called Valley Falls), where Sylvester Scovil next appears. He shows up in 1856, as recorded in the Kansas territorial census, and is still there in the 1860 Federal census, listed as a farmer. (I will spare you the details of how I sorted him out from all the other Sylvester Scovils—and Scovills, Scovels, Scovilles, Schovilles, etc.)

The next 15 years are still a mystery, as I found nothing more until 1876, when he showed up almost 1600 miles further on, in Walla Walla, Washington. He seems to have evaded the 1870 census, which is not surprising considering he would have been crossing through territories that would not achieve statehood for several more years.

What was Sylvester doing in Washington? Did he lead a normal life before breaking into the headlines?

From the Walla Walla Weekly Statesman of May 27, 1876:

Crazy Man.—Some months since we had occasion to notice the mysterious conduct of a man who imagined he seen [sic] spirits, and entered private houses for the purpose of interviewing these messengers from the unknown regions. At that time he occasioned considerable alarm, and the propriety of sending him to the insane asylum was seriously discussed. His insanity, for such it undoubtedly is, quieted down, and for several months he passed along our streets moody, but apparently harmless. Yesterday morning, however, he seemed to have a new attack of his complaint, and entering O’Brien’s Hotel, he rushed up stairs, and without ceremony entering the rooms, occasioned serious alarm. Many of the ladies were awakened from their slumbers to confront a wild, crazy man, and the shrieks that followed can better be imagined than described. The poor unfortunate was at once placed under arrest, and as soon as the necessary hearing can be had before Judge Guichard, he will be sent to the insane asylum.

From the following issue, June 3, 1876:

A Monomaniac.—We made notice in the last issue of the Statesman, that a man, whose name has been ascertained to be Sylvester Scoville, had been arrested for mysterious conduct, supposed to be insanity. Last Saturday this man was brought before the Probate Court for examination as to his isanity [sic]. Doctors Bingham and Burch were called in to conduct the medical examination, and pronounced Scoville a monomaniac on the subject of spiritualism. He is otherwise quite rational. The unfortunate man was born in Connecticut, and is about 54 years old. The Probate Court, upon the written certificate of the physicians, adjudged him insane and dangerous to be at large, and placed him in the custody of Sheriff Thomas, to be by him conveyed to the asylum for the insane at Steilacoom.

Census records show that Sylvester remained in the asylum, now called Western State Hospital, from 1876 until his death on March 10, 1888. He is buried in an unmarked grave in the Western State Hospital Memorial Cemetery, near Tacoma.

Two more articles from the Walla Walla Weekly Statesman indicate that Sylvester’s mental instability was not the worst of his problems:

May 27, 1876:

Insane Asylum.—Dr. Sparling, of Seattle, has been appointed superintendent of the insane asylum. We are not acquainted with the new superintendent, but if he is not an improvement upon the late incumbent, Hill Harmon, then he is a worthless cuss. For years the insane asylum has been a disgrace to the territory, and we can only hope that under the new management it may be something more than a slaughter-pen for the unfortunates who are bereft of reason.

July 14, 1877

Walla Walla Insane.—Dr. Willard, physician in charge, reports the following persons sent from Walla Walla county as now under treatment at the Insane Asylum: Noah Isham, Elizabeth Pitcher, Matt W. McDermott, James Atcherson, Mary Dougherty, John Crow, Sylvester Scoville. Strangely enough when Dr. Willard took charge of the hospital he found these patients, but no record of their previous history or any information in regard to the peculiarities of each particular case. Such carelessness in the management of a public institution amounts to a crime, and shows that Hill Harmon was kicked out of the hospital none too soon.

We can hope that conditions improved under the new management during Sylvester's stay, but at best it would have further broken the hearts of his family back in Connecticut. It's worth noting, however, that despite whatever sins were committed by or against him, despite the difficulties of pioneer life, despite illness and probable abuse, Sylvester outlived all but one of his six siblings. Phoebe, the quilt owner, survived him by 24 years.

Mary Perkins was born in England in 1615, and came to Massachusetts with her family in 1631, on the same ship as Roger Williams (my 10th great-grandfather and the founder of both Providence, Rhode Island, and the Baptist Church in America). She married Thomas Bradbury, who had come to the New World from London in 1635.

What makes Mary among the more notable of my ancestors is her conviction of witchcraft in Salisbury, Massachusetts, at the age of about 77. She was one of the very few convicted women who escaped being hanged; just how is not known.

GenealogyMagazine.com has published an article on Mary Bradbury. I'm not completely confident of its accuracy—it says, for example, that she was convicted at the age of 72, but that is not reasonable given that she could not have been born after her baptism in 1615. Still, it's an interesting article and pulls together some stories that I had not heard before.

Here is the article: The Witchcraft Trial of Mary Perkins Bradbury.

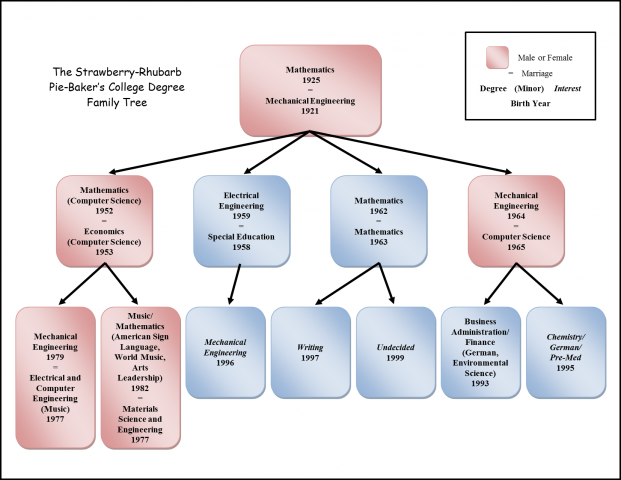

In the first comment to Saturday's Pi(e) post, Kathy Lewis asked about the math legacy of my mother (the one who introduced Kathy to strawberry-rhubarb pie). This inspired the genealogist in me to answer the question visually. (Click image to enlarge. Family members, please send me corrections as needed.)

Math-related fields clearly run in the family, by marriage as well as by blood. Some other facts of note:

- Most of the grandchildren (and all of the great-grandchildren, not shown in the chart) have not yet graduated from college. Their intended fields, where known, are shown in italics. One is very close to graduation, so I've left him unitalicised.

- In each generation from my parents through my children, there's been an even split between mathematics and engineering. However, with the next generation at nine and counting, I doubt that trend will continue.

- The other fields don't come out of nowhere: both of my parents had a vast range of interests.

- With one short-term exception in a time of need, every woman represented here clearly recognized motherhood as her primary and most important vocation, forsaking the money and prestige that come with outside employment to be able to attend full time to childrearing and making a good home. Every family must make its own choice between one good and another; this is not a judgement on other people's choices. Nonetheless, homemaking and motherhood as careers are seriously undervalued these days, so it's worth noting when such a cluster of women all choose to focus their considerable intelligence and education on the next generation. As daughter, wife, mother, aunt, and grandmother, I'm grateful for the choices these families (fathers as much as mothers) have made.

- Engineering is a long-time family heritage. My father's father (born 1896) was a mechanical engineer, and the first chairman of that department at Washington State University. His father (born 1854) was a civil engineer.

Permalink | Read 3285 times | Comments (6)

Category Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Genealogy: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Far be it from me to minimize the intelligence and contributions of Henry Louis Gates, Jr. My own feelings about him are mixed, as I think he acted irresponsibly and reprehensibly in the Cambridge Incident. Not his initial reaction—I wouldn't want to place any bets on my own rational behavior after returning from an exhausting overseas trip and finding myself locked out of my house, then being suspected by the police of housebreaking. But for escalating the affair even after the facts were known. At least I think that I, upon calmer reflection (and perhaps some much-needed sleep), would have been grateful to have had a neighbor notice that someone was jimmying my door, and police willing to be certain the housebreaker was who he said he was.

That aside, however, I can't deny his accomplishments, nor fail to appreciate his contributions to the genealogical field, especially in making it more popular and accessible to many who otherwise would never have given it a second thought. For a while we watched his PBS series, Finding Your Roots, though just as with Who Do You Think You Are? and Genealogy Road Show, it got tiresome after a while: too much hype, too many celebrities, not enough content. His work is serious, and his passion genuine.

Recently Gates was interviewed in the American Ancestors magazine published by the New England Historic Genealogical Society. His passion shows in his answer to the question, Where do you see genealogy in five or ten years? What do you think is going to happen?

I'm working with a team of geneticists and historians to create a curriculum for middle school and high school kids, to revolutionize how we teach American history and how we teach science using ancestry tracing. Every child in school would do a family tree. We think that's the best way—to have their DNA analyzed and learn how that process works in science class. In American history class, we think that's the best way to personalize American history and the nature of scholarly research. For a lot of kids, going to the archives, looking at the census is boring. But if we say, "You're going to learn about yourself, where you come from," what child wouldn't be interested in that?

Really? Really? I'm 100% with him on the idea that genealogy makes history personal and for me far more interesting. I can feel and appreciate his enthusiasm. But can you imagine parental reaction to this particular permission slip? This is several orders of magnitude greater than the privacy violations already imposed on families by the schools. Genetic genealogy is a very young science with innumerable risks and ethical pitfalls. Even those of us who value the genetic information available aren't necessarily thrilled with the idea of our genetic information being "out there."

Medical fears Who else can learn that I have a genetic predisposition to cancer, or bipolar disorder? If I get tested, will I be morally obligated to reveal the results to my family, my doctors, or on an insurance or employment application? Do I even want to know myself? If the school learns such a thing about my child, will that affect their treatment of him? Could they initiate a child abuse claim if we refuse to take whatever steps they recommend based on this knowledge?

Sociological and psychological fears A child discovering that his father isn't the man he has called Daddy all his life. A youthful indiscretion revealed by the discovery of an unexpected half-sibling. Decades-old adulteries brought to light. We like to hear of the DNA-testing success stories, of Holocaust survivors reunited with family members they thought long dead. But there's a darker side to the revelations: as one man wrote, With genetic testing, I gave my parents the gift of divorce. Even if we're certain there are no skeletons in our own closets, or don't care if they're brought to light, can we be so sure about other family members? Can we speak for their wishes? What's revealed about our DNA affects other lives; no man is a genealogical island.

Security fears I have too much respect for hackers and too many misgivings about the NSA to believe any reassurance that the data is secure. And indeed, much of the information desired by those who have their DNA analyzed is only useful if it is shared.

To be sure, there's a lot of very interesting data that can potentially be mined from DNA testing, and I'm not saying I'll never consent. It's tempting, to be sure. But it's not a decision to be entered into lightly, and certainly not one to be imposed on a family by a middle school history teacher. Even one as enthusiastic and as persuasive as Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

I thought it would be easy. I have no small children at home. I have no paid employment. Life at the moment is, generally, calm. Surely it wouldn't be hard to pretend I had a half-time job, and dedicate 40 hours over two weeks to genealogy work. However, this task turned out to be surprisingly difficult. It took 18 days, not 10, to log the 40 hours, and before it was over I found myself heartily sick of genealogy. It was an instructive exercise, however. A few observations:

- I can make a surprising amount of progress if I hole myself up in my office, ignoring phone calls, e-mails, Facebook, and even to some extent my husband.

- Ignoring other responsibilities in order to meet my genealogy goals (or any other specific goals, I suspect) eventually builds up so much psychological pressure (guilt) that the once-pleasurable work becomes a chore.

- Phone calls from grandchildren cannot be ignored.

- My goal was to work in concentrated segments of at least an hour each, but I found that surprisingly hard to manage, and eventually allowed myself sometimes to count the accumulation of smaller time periods. Otherwise, it was too frustrating to find myself with, say, a half an hour to work and yet know I couldn't count it towards the goal.

- The original impetus for this exercise was the expiration of my Ancestry.com subscription. Deciding to renew it took a bit of the wind out of my sails and slowed my progress, but I did eventually pull myself together and finish only one day later than my end-of-January goal.

- I had hoped the push would make a good dent in my accumulated backlog of genealogy work. Ha! Infinity minus anything is still infinity. Still, it really did help, and I made some good finds, though in trying to "beat the expiration clock" I spread my work very thinly, and concentrated more on new data than on entering the old, so the backlog looks more worse than better.

- Having a full year's subscription ahead of me, however, and a plan to put in a steady hour or two each week, I'm hoping some more methodical plodding will bear good fruit.

This is me, eating crow.

I've always had problems with the AARP. I don't like their politics, and I resent the frequent junk-mail reminders that I'm getting older and should sign up. When Porter joined—chiefly to get the AARP discount at Outback Steakhouse—I reluctantly put the card in my wallet, but was ashamed of its presence. Having campaigned for decades against age discrimination, I still don't like the idea of an old-folks organization, and have thus far refused to read their magazine or even check out their website, though Porter says they have some interesting games. It's a matter of priniciple.

As it turns out, some principles go only so far, and mine broke down today. I discovered the AARP discount at Ancestry.com.

Remember my 95 by 65 goal to put in 40 hours of genealogy work by the end of January? The chief impetus for that was the upcoming end of my Ancestry.com subscription, which I had planned to let expire for a while. However, at least until March 4 (after which the agreement may or may not be renewed), AARP members receive a 30% discount on the World Explorer membership. Thirty percent!

Pricing at Ancestry is so complex that I made a spreadsheet just to figure it all out. (Or maybe that's just me.) Not only are there different extents of Ancestry membership (World, or U.S. only), and different time periods (monthly, semi-annually, annually) but their World Explorer Plus membership also provides annual subscriptions to Fold3 and Newspapers.com. The Ancestry website is not nearly as forthcoming with prices as it could be, making comparisons difficult.

Enter the world of the phone and the human interface. I'm not a phone person, but this was worth it. I learned the truth of what was so confusing on the website: The World Explorer Plus membership cannot be given as a gift, and the AARP discount only applies to World Explorer, not U.S., and most importantly in my case, not with the AARP discount. The last was a disappointing loss, but it turns out that Fold3 and Newspapers.com offer a 50% discount to Ancestry.com members, which adds up to only $8 more than if the AARP discount had applied to the World Explorer Plus membership. (Are you confused now? That's why I made the spreadsheet.)

Plus, because I upgraded my membership before it actually expired, they added an extra month to my subscription. That's never happened before, but I was happy to take it. When this membership is about to expire, I'll be sure to call ahead of time to see if the AARP discount is still active, or if there's something else useful. I'd never have known if I'd just let my subscription expire, or renewed online.

I still have problems with the AARP. But I'll take the perk. In this transaction alone, the $16 membership fee saved me $90.