In a letter from my father, 6 April 1985

You mentioned some time back that so many of the AT&T fathers, and mothers too, seemed to have minimal interest in doing things with their children and seemed almost to regard their children as an unwanted product of their marriage. I can only comment that I can think of no activity that pays better dividends than the time spent with the children.. I can comment from experience that whatever time you spend can be returned many times over.

I can attest that his life was in perfect alignment with his words.

Permalink | Read 138 times | Comments (0)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] Glimpses of the Past: [first] [previous]

Here's some more from my father, writing in 1988 about an airplane flight to Denver.

There is much talk about the high level of illiteracy in this country and I suppose that is why all the "do and don't" instructions on the plane are all in the form of pictures with no words to be found anywhere. I have my own type of illiteracy—I often can't understand pictures. There was a picture that seemed to be a man and a woman with something that I could not make out between them, and the line through the picture indicating that whatever the picture represented was forbidden. It wasn't until my trip to Hawaii when I paid more attention to it that I concluded the picture had to do with whether or not the lavatory was occupied. It needs to be recognized that some of us never went to kindergarten and we therefore sometimes need a few words to help us along.

I did go to kindergarten, and still need words to help me along. I never did like those "wordless books" that were popular when our kids were young.

That said, when confronted by a choice between those cryptic heiroglyphics and instructions in a foreign language, I usually have a better (though still minimal) chance of decyphering the pictures.

(I can't say I've been waiting all my life to use "cryptic," "heiroglyphics," and "decyphering" in the same sentence, but now that I've accidentally done it, I find it pretty cool.)

Permalink | Read 234 times | Comments (1)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Glimpses of the Past: [first] [previous] [newest]

There's been a lot of talk about autism, and the autism spectrum, in recent years: what it is, what causes it, why the condition seems to have skyrocketed, what can or should be done to help those dealing with it. I'm not getting into the politics of it all; whether you blame heredity, vaccines, Tylenol, environmental pollution, ultraprocessed foods, random chance, or all of the above doesn't matter for this post. Personally, my own favored "cause" is the explanation I once heard of the high number of children considered "on the spectrum" in places like Silicon Valley and Seattle: Engineers are marrying engineers. I'm only half joking.

From my perspective, 1988 seems recent, but in the 38 years since then much has changed, including autism awareness. In that year, my father attended an Elderhostel program near Pikes Peak, Colorado. This comment from his journal of the occasion stood out:

Mrs. Drummond felt compelled to keep up a conversation as we traveled to her home. They have two children, a girl about 7 and a boy about 5 years old. The boy is Autistic and is in the public school for the first time this year. The disease is rare enough, at least in that area, that she has had to spend a good deal of time instructing the teacher on how to handle the problem.

Today, no one would call autism a disease, nor would they consider it rare. On the other hand, I'm certain there are many parents of autistic children who would say that they are still having to spend a good deal of time educating teachers (also family, friends, and random strangers).

In view of all the excitement over the weather these days, it seems appropriate to publish my father's story of one of my happiest childhood memories, which he called the Great Ice Storm of 1964. If you find yourself struggling under bitter cold, sheets of ice, and loss of power this weekend, I hope you will be able to turn the event into an adventure that your children will still remember with delight sixty years later.

The Great Ice Storm of 1964

by Warren Langdon

In December 1964, while we were living on Haviland Drive in Scotia, NY, an ice storm wreaked havoc throughout the area and left us with an adventure that I recorded in letters to my father and other family members. I recently found carbon copies of those letters and am rewriting them. It is my intent to copy the letters exactly as written except for misspellings and for words that are crossed out. Words that I have added I have put in italics, thus identifying the parts of the story that might suffer distortions caused by my faulty memory.

Part 1

December 9, 1964

Dear Dad,

What an adventure we have had this past weekend! It all started on Friday, the day that Lynn and Linda were supposed to go to the Girl Scout camp on Hidden Lake for the weekend and I was to stay home and baby-sit with the other three children. We all had great plans, but Friday morning brought freezing rain that had not let up by noon. At that time Lynn backed out of the trip, feeling that the weather was not proper for taking the girls out. Just before they were to leave at 3 o’clock the trip was canceled, and the freezing rain continued to fall.

I had been at work all day. The part of the Laboratory that I worked in was housed in a large multistory building that belonged to an entirely different part of the Company. Our offices were in a corner of an otherwise unoccupied first floor. I had not been outside all day and the first inkling I had that things were not normal came when all the lights went out at what I suppose must have been about 5 o’clock. The entrance to our office area was a fairly large room with desks for two secretaries and off this room was a moderately long hallway with offices on both sides. When the lights went out I was the only one in the area and I had to grope my way down the hall, through the entrance area and out to the out-of-doors. Of course it was dark at that time of day and since all electricity was off, there was essentially no light coming into the building. To make matters more interesting, as I was groping my way up the hall a fire engine with siren blaring drove up. (I found out later that some equipment that was running on the fourth floor was connected to sound an alarm in the fire station in the event that the power went off.) I went home and do not remember any difficulty getting there. The streets must have been well salted/sanded.

I arrived home about 6 o’clock to find a fire in each fireplace and candlelight removing the darkness from the house—the power had gone off at 1:50 in the afternoon and that is a time that is etched in my memory, for that is when the clock stopped, and that is what the clock read for better than three days—every time I looked at it.

When I got home Lynn had supper ready—baked beans cooked over the fire in the fireplace. They were burned a little, but they tasted good. All evening long we could hear trees snapping and branches falling as limbs bent and broke under the weight of the ice that was coating them. And in Scotia, every time a limb fell it took down a live power line. We could watch as the whole sky lit up brightly with the red, orange, and yellow light, and often the green that signified vaporized copper. The light was so bright and the sky so completely lit up that I thought it must have been the northern lights, even though they were in the east, but I have been assured several times since that it was all caused by high voltage power lines coming down. I never believed that it could be so bright from so great a distance, but I suspect that the low clouds did much to enhance the effect. But the fire department and the police in Scotia were very busy setting up barricades and otherwise coping with the problems of downed power lines. Our fire department got not one single call on Friday night—mostly, I think, because all the lines that went down in our district were dead when they went down.

Friday night Linda and Alan slept in sleeping bags in front of the fireplace while Nancy, David, Lynn, and I slept upstairs as usual. It was a little chilly upstairs but not bad. Linda watched the fire down stairs and put an occasional log on as she woke up during the night. We awoke Saturday morning to behold an awful mess outside. Almost every tree in our yard had been broken to some extent, although the two oaks in the back and the pines seemed unbroken. But the locusts and the wild black cherry trees were badly hit and they are now rather drastically thinned. The back yard is a mess, but our yard is not nearly as bad as some of the yards nearer Spring Road. But Scotia was far harder hit. Not only has the tree damage been worse, but almost every tree limb that fell took down a power or telephone line or blocked a street.

When the power went off Lynn was caught with a wash done but not dried, so one of the first chores on Saturday morning was to go into the village and see if there was a Laundromat open. At that time I did not realize just how badly the village had been hit since they had power when I came home from work on Friday. Linda and David went with me and we actually had very little trouble. The streets we traveled on were mostly clear and there was very little traffic out. There was enough power in the business district that a Laundromat was open and we dried the wash with no problems. We also went to a drug store that had some power. Their electricity came from two streets (they are located on a corner) and the part that came from Vley Road was on and the part that came from Fifth Street was off. We came home still not realizing just how many live wires were still coming down and how much damage had been done in some parts of the Village. The house of one of the men I worked with was without power for a full week. Things were bad enough that the sheriff’s cars were making the rounds of the Village with sound systems warning people to stay home unless it was absolutely necessary to go out. A state of emergency was declared, but I still do not know what that means. In spite of all the live wires that were falling, the only fatality so far as I know was the Mayor’s dog.

When we got home we made an effort to prop up the little wild plum tree in the front which was sagging badly and had one main branch broken, but beyond that there didn’t seem to be much to do and it didn’t make much sense to start cleaning up yet. We spent the day not accomplishing very much, but not having a hard time of it either. We had plenty of wood—in fact, on Friday, Linda and I had taken a couple of wheel barrow loads to a neighbor whose husband is a traveling auditor and was out of town.

Saturday night we cooked hamburgers over the charcoal grill, doing the cooking in the garage where the car lights helped us see what we were doing. Lynn used paper plates and paper cups as much as possible to cut down on the dish washing that was required since we were not in a position to heat much water. But cooking over the grill gave us a chance to have a good supply for the dishes. As far as I was concerned it was a privilege to wash the dishes as long as there was hot water to do it in. The water in the hot water tank was still rather warm and that, together with what we heated on the grill made dish washing easy.

Saturday night we moved Nancy’s crib down into the living room and we all slept downstairs. Nancy was in her crib; the other children were in sleeping bags in the living room; and Lynn was on a mattress in the living room while I was on the roll-a-way bed in the family room.

I suppose it was inevitable on such a weekend. About 3 a.m. the telephone rang (Don’t ask me how it was that no one had electricity and everyone had working telephones.) and I was told to report to 72 Spring Road as there was a fire there. (The fire station was without power too, so the siren did not blow. Don’t ask me why the power lines were down and the telephone lines were not.) I dressed and got there before the fire trucks did and actually had some trouble finding the place as no one was out to flag me down. I overshot and by the time I got back the fire engines were there. Then I could see considerable smoke coming out of the attic ventilator. It was a case of a fireplace in an interior wall and a hole in the mortar of the chimney. Either heat or sparks had set fire to the wall and it was a rather stubborn blaze. I tended the truck and ran the pump and never got inside, so I don’t know just how bad the damage was. I gather there was considerable damage to the wall but essentially none to the rest of the house. I gather the owners are back living in it now that the power is on.

I see that I am at about the limit of the paper that I can send to Ethiopia for one stamp so I will close and continue later except to say that we got our power back at 8:00 p.m. on Monday and are absolutely none the worse for wear. I’ll tell the rest of the story later.

Part 2

December 15, 1964

Dear Dad,

I left off last week’s narrative telling about the fire we went to at 3 a.m. Sunday morning during our week end without power. As I mentioned, I ran the pump and tended the truck, standing out in the wind and snow flurries and getting very, very cold. I kept thinking how nice it would be to go home after this was all over and have a good hot bath; then I would remember how impossible that was with no hot water, so I just shivered some more. We put the fire truck away by candlelight and returned at 11 o’clock to finish the job properly by daylight. I got home the first time about 6:30 a.m. which meant I no sooner gotten back into bed, after first building up the fires in the fireplaces, than the first of the children started waking up, and there was no more sleep for that night.

Sunday Lynn again went in to the village and did a laundry, primarily to make sure we had plenty of diapers. Both the Dietzes and the Campbells called to offer us any help that we might need. The Campbells were without power only about 28 hours and the Dietzes never did lose theirs. The only thing we thought we might want was a hot bath, but Sunday was a pleasant day and it seemed easier to stay home than to go out, so that is what we did. I did make a point of shaving in some rather lukewarm water but that is as far as we went toward cleaning up. A neighbor lent us his two-burner gasoline stove for our supper, so we had some hot gravy and a hot vegetable to go with some left over roast beef. We also cooked some baked potatoes in the fireplace and we dined like royalty. Of course I didn’t time the potatoes very well and they weren’t done until everything else was gone, but then, what better dessert is there than hot baked potatoes with butter? The gasoline stove got put to good use for heating water and it was a real pleasure to wash dishes under these circumstances.

Sunday night it got cold outdoors and was an official four degrees by Monday morning. Inside it was 44 degrees in our hall where the thermostat is and it was less than 34 degrees in the upstairs bathroom. (My recollection is that we had a Celsius thermometer hanging in the bathroom and it read barely one degree.) But in the family and living rooms it was warm enough that no one suffered. Monday there was no school and I decided not to go into work. Lynn packed up and went in to the Campbell’s in Scotia and they all had hot baths and a hot lunch while I watched the fires at home and took advantage of the deserted house to proof-read a rather lengthy report we were having to write. After lunch I abandoned the house for an hour or so and went also to the Campbell’s and had a hot bath. That was a feeling of real luxury! I think that the thing I missed most during the time the power was off was copious amounts of hot water. Lynn also used the visit to the Campbell’s to do another wash and to put some of our freezer foods in Mrs. Campbell’s freezer. Fortunately we had not had much perishable in our freezer when the power went off. There was bread which didn’t matter, some frozen vegetables and frozen strawberries that we could eat before they spoiled. But our really valuable frozen foods—the 12 quarts of blueberries—Lynn put in Mrs. Campbell’s freezer. Things were pretty well frozen on Monday morning, but were beginning to soften. The only thing we lost was about a gallon of ice cream.

As I returned from the Campbell’s I noticed the power company crew working on the broken line on Haviland Drive, and others were working on Spring Road, so it looked like we would have power by sometime Tuesday for sure. I returned to the Campbell’s for supper and a very pleasant dinner it was. Linda and Alan were invited to spend the night with the Campbell children, and they did—-not because of any hardship at home but because they enjoy playing with the children. The rest of us returned home for another night without heat and light, but sure it would be the last such night. And as we sat before the fire the lights suddenly went on. It was almost exactly 8:00 o’clock—-the power had been off just over 78 hours. So with the furnace running at last we knew that we could let the fireplace fires go out and we set about the business of finishing the defrosting of the freezer and the refrigerator, and giving both of them a good cleaning. And when we finished that job we probably got colder than at any time during the weekend. The fires had died considerably while we had been working, and the furnace had only barely begun to raise the temperature in the house. In fact, when I left for work on Tuesday morning the furnace had been running for eleven hours and the temperature was only up to 63 degrees. Monday night Nancy and David again slept before the living room fireplace, but Lynn and I slept upstairs where the electric blanket would nullify the effect of the cold bedroom. And so ended the big adventure. No one suffered and no one was unhappy. But poor Nancy—-in the years to come she will complain that she can’t remember a bit of it.

Editor's commentary:

- If, like me, you cringed when you read about using our hibachi-sized charcoal grill in the garage, know that (1) our garage was drafty, and (2) my father was not only an engineer but a fireman, and well aware of the dangers of burning charcoal in close spaces. I certainly don't recommend the practice these days, but he knew what he was doing and we were in no danger.

- In those days power lines and telephone lines were two different things, with the power wires being strung higher than the phone wires, and thus perhaps more vulnerable. "Landline" phones (there was no other kind) carried their own power, independent of the electrical service.

- His apparently incongruous concern over the cost of postage to Ethiopia was because that is where my father's sister and her family, to whom he sent copies of his letters, were living at the time.

- I am still puzzled by his description of the frozen food situation.

- Why, if it was 4 degrees outside, did they worry about frozen food? Why didn't they just put it outside? If they were worried about animals getting to it, then if my memory of the temperature of our garage was correct, that would have done just as well as a convenient, walk-in freezer.

- How on earth did we let a gallon of ice cream go to waste? Surely our family of six could have polished that off easily enough.

- Poor Nancy, indeed. The ice storm is one of my most cherished memories. What more could a child want? The family was together, school was closed, and we “camped out” at home. Toast never tasted so good as that which we grilled over the fire on our marshmallow sticks. I liked being responsible for keeping the family room fire going. Ordinary life was put on hold while we enjoyed working and playing together. (You can tell I was not the one responsible for making sure there were enough clean diapers.) The sun turned the ice-covered world into a crystal paradise, and the exploding transformers were as good a show as any fireworks display. While it is true that we always enjoyed being with the Campbells, the way I remember the night spent at their house was that I felt I was supposed to be grateful for heat and hot water and the chance to have a “normal” night, but I really resented missing the last few hours of an enormously pleasurable adventure. I suspect I didn’t communicate this to my parents at all at the time, but I’m surprised at how strong the memory of the disappointment is to this day.

Permalink | Read 270 times | Comments (5)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] Glimpses of the Past: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Christmas 2025 has come and gone, but I'm not waiting 11 months to share this fun peek at things you might not know about "A Charlie Brown Christmas." I hope you enjoy it as much as I did.

As you might guess, I'm one of the dinosaurs who remembers waiting eagerly for the one and only time slot of the year we could watch this show. Only in my case, it didn't matter whether Snoopy's doghouse was red or blue—not on our black and white television set.

Permalink | Read 241 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Glimpses of the Past: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

As I've mentioned before, I've been enjoying going through (and digitizing, where possible) my father's old journals and letters. I particularly like coming upon examples of his sense of humor, which often relied on either exaggeration or understatement, or both. The following, from a mid-1988 letter, made me smile this morning.

Last Monday while I was carrying an ancient and defunct television set out to the trash, my back gave way. It was not a heavy load--certainly not more than 20 pounds--but even though I had no trouble getting it up the basement stairs and through the house, the problem came without warning as I was descending the front porch steps.

Over the next several days, interspersed with other news, Dad reported feeling fine enough to spade the garden, then feeling considerably worse, finally consulting a doctor and getting x-rays which revealed a compression fracture. He next visited an orthopedic specialist, who was not concerned about the x-ray results, since they showed only something minor that might have happened many years ago. Based on Dad's description, the doctor concluded that the problem was muscular, and prescribed "time and a heating pad." When Dad then asked what kind of activities he could could indulge in, the doctor replied, "Anything you want." For anyone reading this who knew my father, the alarm bells are now going off....

Dad did limit his activities to the extent that he did not go bungee jumping, nor bowling, the latter having landed him back in the hospital on a previous occasion when his surgeon had told him that he could "do anything you feel like doing." He did decide that that heavy gardening was still on the table, and paid for that the next day, but the orthopedic doctor was apparently right, and the references in his letters to his back petered out. In the end, he was left with the following conclusion:

I guess this confirms my feeling that television is bad for you. But on the other hand, if you have one, keep it.

I don't usually pay attention when Hollywood celebrities preach about issues unrelated to their own professions, and at my age, I've finally learned to take even the confident pronouncements of experts with a grain of salt. But as an old Star Trek fan, when I heard that Mr. Spock (aka Leonard Nimoy) was narrating a special on the climate crisis, I had to watch. It's 22 minutes long and worth seeing in its entirety.

If you're not frightened or angry, you may at least be amused.

The year was 1978. We had recently graduated from college, gotten married, and begun our careers. The year before, we had moved into our first house; the following year we would welcome our firstborn child. Life was good.

Little did we know that doom was on our doorstep.

'Way back in the 1980's, my family enjoyed spending time with good friends who owned a summer camp on a lake in Vermont. The following is a story from the year my father made the mistake of being part of camp-opening at the beginning of the season. Names have been abbreviated to protect the innocent and the guilty. I hope you find that this tale of minor summertime woe brings you a little bit of cheer this Christmas season, if only because it didn't happen to you. It's funny how we often find misfortune to be humorous as long as it's sufficiently distant in time and space. But don't feel bad about that. Dad would have laughed—that's why he wrote it the way he did.

Friday, 5 June 1987

I was the first to arrive. I expected D. around 9 or 9:30, A. and J. around 2-3 a.m., and E. even later. What I found in the cabin did not leave me overjoyed. When the camp had been "winterized" the refrigerator had been unplugged and the doors propped open as they should have been, but what they failed to do was remove what appeared to have been some popsicles and something that had been wrapped in aluminum foil and was about the size of a pan of brownies. Whatever it was, it had long ago spoiled and left a very unpleasant odor in the kitchen and a mess in the freezer compartment. At this point I went out and bought some sponges for cleanup and some bottled water as the water system had yet to be made operable. When I returned, I set about cleaning up. In addition to the mess in the freezer, the refrigerator was full of what I at first thought were mouse droppings, but which I later concluded were egg cases as they were too uniform and shiny to be droppings. They may also have been seeds that were stored there by some creature for future use. The refrigerator door contained a shelf with depressions for holding a dozen eggs and each depression held at least a half dozen of these seeds or whatever. Anyway, with sponges and ammonia I cleaned up everything but the smell. Out of all this I came to two conclusions: 1) Next time I won't be the first to arrive, and 2) when the guys go up this fall to close up the camp, J. should go to take care of the details that the guys tend to forget. As you will see later, this latter conclusion was reinforced during the weekend.

About 9 o'clock I got a call from E. saying that D. was leaving Middletown about 8 o'clock which meant he would not arrive until around midnight. I had held off having dinner until D. arrived, but I now decided that D. would have eaten by the time he arrived and it was time for me to find some dinner. I went to the Checkmate restaurant and found they were closed to the point that they would sell only ice cream. While I was wondering what I would find open at that hour of the night, I concluded that there was no reason I couldn't fix my own dinner. So I went into Fairhaven and to the Grand Union where I bought the ingredients for a fried egg sandwich and then returned to camp where I fixed just that.

D. arrived around midnight. He snacked a little and we went to bed about 1 a.m. J. and A. arrived around 2:30.

Saturday, 6 June 1987

E. arrived about 6:30 and with that we all got up. A., D., and E. got the water system working after a little problem getting the pump primed. But when they turned on the water to the house, a large spray emerged from an elbow in the cold water line to the bathtub in the main bathroom. Clearly they had not opened the faucets when they drained the system. So while the pump-installers went to play golf, J. and I tackled the elbow problem. Naturally the elbow was old and nothing like it has been made in years. The people at Gilmore's Hardware threw up their hands, but at Tru-Value they put together a combination that would do the job. Having finished this repair, we turned on the water, only to find a stream pouring out from under the house. A soldered joint in the copper tubing to the wash basin in the small bathroom had come apart and that is where the water was coming from. J. and I went back to Tru-Value and bought a torch, solder, and flux and made the repair. This would not have been difficult except that we were working with a clearance of only about six inches between the house and the ground, and not only was the working space cramped, but I also made a reasonable effort to avoid setting the house on fire. So now we turned on the water again and all was well until I ran water into the wash basin. Now water gushed out of the basin drain pipe which was broken near where the copper joint had come apart. Since there was no leak except when the basin was used, the solution this time was to pass a law that the basin would not be used until repairs had been made.

Now we could open the line to the water heater so we could wash dishes in hot water. I opened the valve, and was showered from the water pouring out of two big cracks in the copper line into the heater. So once again we went to Tru-Value where we bought some couplings and a length of tubing. I cut out the bad section and soldered a new piece in its place. Now we could turn on the water again, and this time water sprayed from an elbow on the bathtub in the small bathroom. By now it was nearly closing time for Tru-Value and besides, we didn't dare go in that store again today. So we went to a hardware store in Fairhaven, but they did not have exactly what we needed to put together a substitute elbow, so we returned to camp and resorted to heating our water on the stove.

In the meantime, E., A., and D. had not only gotten the water pump running, but had played 27 holes of golf, and put the dock into the cold Vermont lake on a chilly and windy day. So we had a light supper of hot dogs before everyone fell asleep, woke up, went to bed, and fell asleep again.

Sunday 7 June 1987

We were slower getting up this morning than yesterday. I got up about 8 o'clock and J. and D. followed at decent intervals. Even E. did not sleep as late as A.. The first trip out was to Tru-Value (where else?) for the needed elbow, which I installed, and we soon had hot water. I consider hot water one of the most luxurious necessities for the good life at a camp, or anywhere else.

Permalink | Read 363 times | Comments (1)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Glimpses of the Past: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

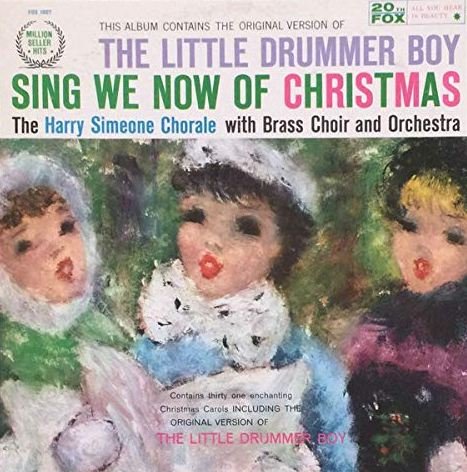

We have so many wonderful Christmas albums, collected for well over half a century, many wonderful, wonderful works reaching from the 21st century back to almost as long as Christmas music has existed.

But the one that most strongly and emotionally says Christmas to me is the Harry Simeone Chorale album, "Sing We Now of Christmas." It was released in 1959 and is my earliest memory of Christmas music. To my great joy, I recently found the album available on YouTube. The cover is a little confusing, because it shows the title as "The Little Drummer Boy," and the image is different. But the songs are the same. This link, Sing We Now of Christmas, will take you to a playlist where you can hear the whole album in order, or return and play your favorites.

I realize that my love of this recording of Christmas songs is wrapped up in the aura of a very happy childhood and all that I loved about the Christmas season, so your mileage may vary. But, as objectively as I can manage, I maintain it's one of the best compilations for telling the story of Christmas coherently through song while including both the old familiar carols and lesser-known songs from more distant times and places.

I had an idyllic childhood. Not perfect, but as close to that as anyone I know. And one of the best parts, I now realize, was growing up with engineers.

Schenectady, New York, where I spent the first 15 years of my life, was the home of the General Electric Company. As it did the skyline, GE dominated our lives, night and day. My father was an engineer, as was his father, and his father's father, and he worked in GE's General Engineering Laboratory. My parents met there, where my mother, a mathematician, also worked. Many of our closest friends were engineers or employed in related fields. Schenectady in those days was a hotbed of science-and-engineering-types, and as far as I could tell, everyone I knew was smart. Smart was normal, and not just among the scientific folks. I suspect that living in Schenectady in its heyday resembled what I imagine living in Silicon Valley or the Seattle area is today.

I'm not talking about genius-level, though there were certainly some of those, but rather down-to-earth people with practical experience and skills, who also read a lot and loved to have discussions about ideas and on just about any subject.

Not that I appreciated it at the time as I should have; I took it for granted. But my recent "archivist" work with my father's journals and other writings has made me realize what a blessing it was to grow up in such a community. They even had their own way of speaking: their conversations were filled with jokes and wordplay, exaggerated and understated language, and what I realize now was an advanced everyday vocabulary. It wasn't until I had had much more experience outside of our parochial bubble that I realized that there are many people who find what I consider a normal vocabulary to be a sign of arrogance, who take the exaggerated/understated language literally, to the point of misunderstanding or even offense, and who either don't understand or don't appreciate the humor.

It takes all sorts and conditions of men to make a world, many of them wonderful. If you understood the "sorts and conditions of men" reference, you are part of a different distinct community, one I did not come to recognize and love until some 30 years ago. Appreciating other cultures and especially loving one's own are not mutually exclusive conditions.

What chiefly concerns me is that we seem to have entered an age when differences are being replaced by diagnoses. The other day, a new friend was telling me about her son, who in high school was triply exceptional: He excelled in academics, in music, and in sports. It's not uncommon to see people who do very well in two of those areas, but three is a rarity. At one point, he was moved to express the concern that he might be "on the spectrum." What social pressures drive an obviously intelligent, capable, and well-rounded child to label himself with a diagnosis? Why do teachers and doctors (and even parents) put so much effort into finding boxes into which they can squeeze children?

As I told my friend, in my day, in my world, we used another term to describe being "on the spectrum."

We called it normal.

Permalink | Read 310 times | Comments (1)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Glimpses of the Past: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Working my way through my father's vast collection of writings, I occasionally find a gem I wish to share.

(Okay, so "vast" is a relative adjective, and perhaps an exaggeration—it's not as if I'm working through the letters of C. S. Lewis or something—but in personal terms it's accurate.)

This came from Dad's 1987 journal documenting his Elderhostel experience at Ferrum College, in Ferrum, Virginia. The program is now called Road Scholar, and no longer has the age restriction, but at that time it was primarily for those over 65, that being the age at which most people retired and could go on such adventures.

Also at the college were a group of gifted 6th graders from nearby Martinsville. They also were at the ice cream social and were told by their teachers to mix with the old folks, so it turned out to be a pleasant evening. I think the future governor of Virginia may have been amongst them. One of the women asked the boy about what they were doing, and then said, "I'll bet you didn't expect to see so many old folks here."

He replied, "I don't know, I haven't seen any yet."

Smart and wise. I could envision voting for him.

Permalink | Read 418 times | Comments (0)

Category Travels: [first] [previous] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Glimpses of the Past: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I was 15 when Martin Luther King, Jr. was killed.

All in all, 1968 was quite the year. The assassinations of King and of Robert F. Kennedy (Sr.), race riots all over the country, the horrors of the Vietnam War, the capture by North Korea of the U.S.S. Pueblo, the Prague Spring and the subsequent crushing of Czechoslovakia by the Soviet Union, madness on college campuses here and in Europe, the disastrous Democratic National Convention in Chicago. On the plus side, NASA's Apollo program was going strong, and the Apollo 8 mission gave mankind its first look at the far side of the moon.

I was privileged at that time to be in the class of Jim Balk, the best history teacher I ever had, and so was primed to be more aware of what was going on than usual.

Personally, 1968 was also the year of our family's world-expanding cross-country automobile trip. My father had grown up in the State of Washington, but we children had never been further west than Central Florida. Granted, it would have been even more eye-opening for me had I had not spent so much of our travel time with my eyes glued to Robert Heinlein's The Past Through Tomorrow and other books we'd picked up from my uncle as we travelled through Ohio. I am not proud of the fact that science fiction could hold my interest far longer than the amber waves of grain or the purple mountain majesties. Nonetheless, it was an amazing and important experience, as would be my first trip to Europe the following year.

Nineteen sixty-eight was the midpoint of a dark, tumultuous, and very strange time for our country. Right and wrong, good and evil, truth and lies, beauty and ashes—the world was turned upside down and shaken. Did we emerge from that era stronger and better? It was indeed followed by a few decades of apparent recovery and progress, but looking back I wonder if we were merely in the calmer eye of the hurricane. For several years now it has felt to me as if the winds of the 1960's have returned with surpassing strength.

The assassination of Charlie Kirk took me right back to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. I had learned from Mr. Balk that in that tragedy, the civil rights movement lost its best hope for non-violent progress, and he was proved right. King's non-violent legacy was "honored" by rage and riots.

We must do better.

Charlie Kirk believed strongly that we need to keep talking with each other, that when we stop talking, violence rushes in to fill the gap. That's why he loved going to college campuses and giving students an open mike to debate with him.

Shock and grief naturally lead to anger, but we need to get through that stage quickly, learn the lessons of 1968, and choose to honor Charlie Kirk by demonstrating and promoting the values by which he lived and worked. Charlie Kirk wasn't weak, and he did not mince words. From what I have seen—which I admit is only online and not personal—he had the same kind of strength and wit you see in the Gospel accounts of Jesus. Not many of us have either that strength or that wit, but we would do well to aim in that direction.

I didn't play a lot with dolls as a child, nor with trucks either. I had both, and enjoyed both, along with sundry other toys: blocks, Tinker Toys, laboratory equipment, tools, toy guns, childhood games, stuffed animals, a (real) bow and arrow set, a hula hoop, a baton for twirling—normal childhood stuff. I was eclectic in my tastes with no overwhelming preference for anything, except I suppose for reading books, climbing trees, and exploring in the woods. So, as I said, I didn't play much with dolls. But the dolls I did have were babies or young children, and they were simple, the better to encourage imaginative play.

So my heart skipped a beat when I saw what one Australian mother has done to "rescue" old, worn-out dolls of the more recent type. I never liked Barbie dolls, certainly not the Bratz and other strange-looking creatures that passed for dolls when our daughters were young. This woman brings beauty from ashes.

This seven-minute video will warm your heart. Not only watching twisted ugliness turned normal, but especially listening to little girls with much more heart and common sense than the jaded, angry toy manufacturers.

This is another post I've pulled up from my long backlog. I wrote it in 2015, when the story was new, but for some reason it languished for more than 10 years! I don't know why; the post was complete and I still love the story.

The inevitable question is, "Where are they now?" What has happened since that bright beginning? Tree Change Dolls has an Etsy site, which appears to concentrate on helping others revive their own dolls, but occasionally offers some of her own creations, which she announces on her Facebook site.

As with any good thing, there are detractors, such as the doll collectors who think she is ruining the dolls, some of which are collectable and worth money in their original form. (Though probably not when found worn-out and broken.) More disturbing are those who say they hate the Tree-Change dolls because they promote the idea of natural beauty instead of heavily made-up and sexualized children's dolls. (That's the impression I got; I didn't spend much time in that unhappy land to find out more.)

"Where does the name come from?" is the other question that intrigued me. Google Search brought up this AI answer:

A tree change is a move from an urban or city environment to a more peaceful, nature-focused rural or regional area, often inland, to embrace a simpler and healthier lifestyle. Unlike a sea change, which involves moving to a coastal area, a tree change focuses on reconnecting with the natural landscape, such as rolling hills, mountains, or countryside, to escape the pressures and fast pace of city living.

Well, that fits, but it struck a discordant note for me because that's not what "sea change" means. Here's the interesting story of the term, from Merriam-Webster:

In The Tempest, William Shakespeare’s final play, sea change refers to a change brought about by the sea: the sprite Ariel, who aims to make Ferdinand believe that his father the king has perished in a shipwreck, sings within earshot of the prince, “Full fathom five thy father lies...; / Nothing of him that doth fade / But doth suffer a sea-change / into something rich and strange.” This is the original, now-archaic meaning of sea change. Today the term is used for a distinctive change or transformation. Long after sea change gained this figurative meaning, however, writers continued to allude to Shakespeare’s literal one; Charles Dickens, Henry David Thoreau, and P.G. Wodehouse all used the term as an object of the verb suffer, but now a sea change is just as likely to be undergone or experienced.

So, a sea change is a transformation, but not specifically moving to the seaside to escape city life. However, "sea change" and "tree change" are apparently used in that way in Australia (at least on the one real estate site I checked), so the name of these dolls that have moved to a simpler, happier life makes perfect sense.

Permalink | Read 1512 times | Comments (0)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Glimpses of the Past: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Having lived through more than seven decades of holidays, I decided it would be of interest (to me, if no one else) to consider how the various annual celebrations have changed, or not changed, as I've lived my life.

As a child, I knew that holidays were about three things: family, presents, and days off from school. Not necessarily in that order—since family was the ocean in which I swam, I didn't necessarily recognize how central it was to our observances. The only celebration from which we children were excluded was my parents' anniversary. I remember being sad about that as a child, and I admire those who celebrate anniversaries as the "family birthday." What a great idea! But "date night" was unheard of in that era, and their anniversary was one of the rare times my parents would splurge on dinner in a restaurant.

Yes, folks, basically the only time we ate out was on vacations, where Howard Johnson's—with its peppermint stick ice cream—was the highlight. Solidly middle class as we were, with an engineer's salary to support us, restaurant meals simply did not fit into our regular budget. "Not even McDonalds?" you ask. Brace yourself: I was born before the first McDonalds franchise. But even when our town did get a McDonald's, the idea of paying someone to fix a meal my mother could make better at home seemed crazy.

But back to the holidays. I'll go chronologically, which means beginning with New Year's Day, which could just as well go last, as New Year's Eve. Other people may have celebrated with big bashes and lots of champagne, but we almost always spent New Year's Eve with family friends, either at their home or ours. My parents and the Dietzes had been friends since before any children were born, and by the time each family had four we made quite a merry party all by ourselves. I think the adults usually played cards, and we kids had the basement to ourselves. Of course there was that other important feature at a party: food. Lots of good food, homemade of course.

Those who didn't fall asleep beforehand counted down to the new year, and toasted with a beverage of some sort. The adults may have had a glass of champagne. One year Mr. Dietze set off a cherry bomb in the snow, which was amazing (and illegal) in the days before spectacular fireworks became ubiquitous. I miss the awe and wonder that rarity engendered. After a little more eating and talking, we gathered up sleeping children and went home. As it was the only time of the year we were allowed to stay up to such an hour, that too was a treat. Once a year past midnight is still about right for me, though sadly it didn't stay that rare.

Valentine's Day was next. This was not the major holiday it is today, and it was mostly child-centered. In elementary school we created paper "mailboxes" for delivery of small paper Valentines to our classmates; Here's an example of what they looked like. (Click to enlarge.) Some of them may have sounded romantic, but nothing could have been further from our minds. It was just a friend thing, and we enjoyed trying to match the sentiments with the personalities of our friends. Back home, if there was anything romantic about it for my parents, I missed it, being far too concerned with chocolate, and small candy hearts with words on them. Sometimes I'd make a heart cake, formed using a square cake and a round cake cut in half, and decorated with pink frosting and cinnamon candy hearts.

There were two more February holidays that no one celebrates anymore: Abraham Lincoln's birthday on the 12th, and George Washington's on the 22nd. We would get one day or the other off from school, but not both. Nowadays they've morphed into President's Day, which is in February but I never remember when because it keeps changing.

March brought St. Patrick's Day, which was bigger in school than anywhere else, chiefly through room decorations with green shamrocks, leprechauns, and rainbows with pots of gold. In elementary school, some of our neighborhood kids had formed a small singing group—we mostly sang on the bus, but one year our teacher heard about it and persuaded us to go from classroom to classroom singing what Irish songs we knew. Back then, my family didn't know we had some Irish ancestors, so as far as I can remember, the holiday never went beyond the school door.

Easter, of variable date, was of course a big deal. Unlike Christmas, it had mostly lost its Christian significance in favor of bunnies and chicks, eggs and candy. Except for when we were with our grandparents and had to dress in our Easter finery and go to church. The going to church part was okay; the finery not so much.

Easter, of variable date, was of course a big deal. Unlike Christmas, it had mostly lost its Christian significance in favor of bunnies and chicks, eggs and candy. Except for when we were with our grandparents and had to dress in our Easter finery and go to church. The going to church part was okay; the finery not so much.

We kids would put out our Easter baskets the night before, and awaken to find them filled with candy; often toys appeared also. Our baskets were sometimes bought at a store, but often homemade—I remember using a paper cutter to make strips from construction paper, and weaving them into baskets.

For me, the best part was our Easter egg hunt. None of this plastic egg business! We had dyed and decorated real hard-boiled eggs beforehand, and our parents hid them around the house, supplemented by foil-wrapped chocolate eggs, before going to bed on Easter Eve. What a blessing it was to live where it was cool enough at Easter time that eggs could safely be left overnight without fear of spoilage or melting.

Easter dinner was almost always a ham, beautiful and delicious, studded with cloves, crowned with pineapple rings, and covered with a glaze for which I wish I had the recipe. I know we did not always have a "canned ham"—for one thing, I remember the ham bone—but the experience of a canned ham was memorable, since they had to be opened with a "key" at risk of life and limb—or at least of mildly damaged fingers.

May brought Memorial Day, which was always May 30, not this Monday-holiday business. When it fell on a school day, it was a day off, which we always appreciated. There was usually a Memorial Day parade, in which we sometimes participated, with band, scout, or fire department groups. There was always something related to the real meaning of the holiday, but we kids never paid attention to the speeches. Our family was well-represented in wartime contributions, but rarely talked about them, and no one had died, so the holiday has no sad associations in my memory.

Mother's Day was in May, also; what I remember most was fixing breakfast in bed for our mother. For some reason, in those days, eating breakfast in bed was regarded as something special. I have no idea why. For me, the practice is associated with being sick, as back then children were expected to recuperate in bed for a ridiculously long time. We even had a special tray, with games imprinted on it, for sick-in-bed meals. Why a healthy adult would voluntarily eat a meal in bed is still beyond my comprehension.

Mother's Day was in May, also; what I remember most was fixing breakfast in bed for our mother. For some reason, in those days, eating breakfast in bed was regarded as something special. I have no idea why. For me, the practice is associated with being sick, as back then children were expected to recuperate in bed for a ridiculously long time. We even had a special tray, with games imprinted on it, for sick-in-bed meals. Why a healthy adult would voluntarily eat a meal in bed is still beyond my comprehension.

We sometimes had outings on Mother's Day, and otherwise just did our best to make sure that at the end of the day Mom was in no doubt that she was a mother many times over.

Father's Day, in June, was also low-key, although it was a bit more exciting in the years when it coincided with my brother's birthday.

Independence Day was, like Memorial Day, an occasion for parades and speeches. Our neighborhood usually had its own parade, with decorated bicycles and scooters. Occasionally we would go somewhere to see a public fireworks display, which wasn't anything like the spectacular events seen these days; nor did ordinary people generally have fireworks. Sometimes we had sparklers, and the little black dots that burned into "snakes" when you lit them. One time our neighbors had imported some mild fireworks from a state where they were legal, and we enjoyed them—all but my mother, who protested by staying inside and playing the 1812 Overture loudly on our record player (which, by the way, was monophonic).

August was entirely bereft of holidays, though we kids were busy squeezing the last drops out of our summer vacation from school. Since Labor Day was always on a Monday even before the Monday holiday bill came into being, and school always started right after that, the week or two beforehand was a favorite time for family vacations. This holiday was completely divorced from what it was intended to honor; I think I was in college, or even later, before I made the connection with the labor movement and unions.

October 12 was Columbus Day, as it will always be for me. Its chief value was in being a day of vacation. I could tell you that "In fourteen hundred and ninety-two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue," and that his boats were the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria, but that's about it.

Now Hallowe'en, that was a children's holiday! We didn't have it off from school, unless it fell on a weekend—and if it did, our schools were certain to celebrate it anyway. Costumes—usually homemade, often very clever—a parade around the school, and no doubt some special treats were the order of the day. Parents were invited to watch the parade, which was almost always held outdoors. Most of the kids walked to school, and most had parents at home who could come. Some costumes obviously had more parental help than others, but none that I recall were store-bought, nor were there any of the outlandish, sexualized, and violent costumes I've seen today—or even 35 years ago when I watched Hallowe'en parades at our own children's elementary school. Today's society would no doubt be horrified, however, at our Indians with war paint and bows and arrows, our cowboys and soldiers with toy guns, and our knights with swords.

At night, trick-or-treating was nothing like it is today. For one thing, there wasn't nearly as much loot, since we were restricted to our own neighborhoods, and most households gave our much smaller quantities of treats than is common today. None of this business of parents driving their kids all over to increase their hauls, no trunk-or-treat, no candy distributed at businesses and malls; there was little commercial about it. But we sure had fun, and much more freedom, being turned loose to roam freely within the set bounds of our neighborhood, without regard for darkness or danger or costumes that were difficult to see out of and were not festooned with reflective tape. Younger children went trick-or-treating with their parents—who had the grace to stay in the street while the children rang the doorbells on their own—or more likely, older siblings, who tended to stick a little closer in hopes some kind neighbor would offer the chaperones some candy, too. Back home, we'd gleefully sort through our haul, occasionally trading with siblings, without any concerned parents checking it out first. And of course we ate far too much candy. Only the oldest of my brothers had the strength of will to ration his; the rest of us finished ours up within a week, but he usually had some left in the freezer until the following Hallowe'en.

Most of the time, the creation of my costume was a father- and/or mother-daughter collaboration that I looked forward to all year. Offhand, I remember being a clown, a cuckoo clock, a salt shaker (to go along with my best friend, the pepper shaker), a parking meter, and a medieval knight, among others that will not immediately come to mind. After elementary school, my Hallowe'en costume days petered out, except for one year after we moved to the Philadelphia area and a group of my friends persuaded me to make the rounds with them. That's when I discovered why they were still clinging to childish pursuits: we were in a wealthier neighborhood, where rich people gave out full-sized candy bars!

Another treasured family project was carving pumpkins into jack-o-lanterns. We used real knives to cut as soon as we were responsible enough to handle them, and always illuminated our creations with candles, even though a finger or hand was bound to be mildly burned in the lighting process. Often we kept the seeds when we hollowed out the pumpkins, salting and roasting them. It was so much fun!

But there was a worm in the apple: One year, when I was at a very tender age, our jack-o-lanterns were set outside on our porch, as usual. A gang of teenage boys came rampaging through the neighborhood and viscously smashed our creations. It was heartbreaking. I still remember the sound of their stomping feet on the porch, and their gleeful yells.

On the brighter side, with some help from my mother, I once created a Hallowe'en party for my friends, with a "haunted house" in the basement, games, a craft, food, and watching Outer Limits on our little, black and white television set. (I've set the video to show just the opening theme. If you happen to watch the whole thing, and get hooked, Part 2 is here.)

As with the best holidays, there was good food, not just candy. Apple cider—real apple cider straight from the farm, unfiltered and unpasteurized, a delight that few know today. Sometimes cold, sometimes hot and mulled, depending on the weather, which at Hallowe'en in Upstate New York could be just about anything. Apples themselves, tart and delicious, of varieties difficult to impossible to find today. My mother's homemade pumpkin cookies! And pumpkin bread! A plate of cinnamon-sugar donuts, sometimes homemade but often store-bought and nonetheless delicious. Sometimes popcorn, too.

Thanksgiving. We frequently had guests for Thanksgiving dinner. My father's parents lived 200 miles away, and while it wasn't the three-hour trip it is today, it was short enough for us to get together for Thanksgiving. If it wasn't my grandparents sharing our Thanksgiving dinner, it was friends, and sometimes both. The meal was pretty standard: typically turkey, mashed potatoes, gravy, stuffing, sweet potatoes, peas, creamed onions, Waldorf salad, cranberry sauce, and rolls, with pumpkin and mincemeat pies. Once we acquired a television set (which happened when I was seven years old), there were parades on TV in the morning for the kids, and football games in the afternoon for the men. The women, no doubt, were cooking! Much later, when we lived in Pennsylvania and had grown up a bit more, the annual "Turkey Bowl" in our own backyard attracted enough friends to make an exciting touch/tag football game in the crisp November afternoon.

And finally, the best for last: Christmas.

These days, there is a Great Divide in the way Christmas is celebrated: Christian and Secular. In my youth it was not so. Christian or not, we all knew the origins and history of the occasion, and everywhere—in stores, in schools, in the public square—Santa, reindeer, snowmen, Christmas trees, presents, Mary, Joseph, Jesus, animals around the manger, shepherds, and angels mingled happily together. Even the Star and the Three Wise Men worked their way out of their proper setting of Epiphany to join the joyous throng.

I loved choosing and decorating our Christmas tree, especially the many years when we cut our own. Christmas tree farms back then were not what they are now, with their carefully-shaped trees in neatly-planted rows. Each tree had its own personality, and we often had a choice among several varieties. Finding our special tree was an adventure I looked forward to every year. The freedom of choice, and cutting the tree ourselves, were important to me. But somehow I never minded when we ended up adopting orphan trees: those chosen and cut down by other customers, then abandoned after some flaw was discovered. Our hearts went out to the poor things, often beautiful in our eyes. And our decorations easily accommodated any flaws.

Tree decorating in our household followed a standard pattern. After trimming the branches to his satisfaction, my father would set the tree in a large can (#10 comes to mind, but I can't be sure) that he filled with sand and mounted in a wooden frame that he had made. It was placed on a sheet and dressed in a homemade Christmas tree skirt. At that point, he put the light strings on. The lights were multi-colored, and much larger than the tiny lights that later became popular. Unlike the practice that continues in Switzerland today, our lights were not real, lighted candles. But burns were still possible: those incandescent bulbs could get quite hot, and Dad had to be careful with their placement.

As soon as that was done, the whole family went to town on the tree! Decorating was a joyous family affair. Each year we created anew popcorn strings, using red string and large-eyed needles. These went on first, after the lights. (Birds enjoyed the popcorn after the tree was taken down.) We had plastic ornaments that were put on the lower levels, where toddlers could reach. We had lovely glass ornaments for higher places. We had an ornament handmade by my grandmother, and several made by young children. Atop the tree was either a star with a light in it, or a glass spire, depending on our mood. The pièce de la résistance? Draping the branches with "icicles." These are hard to explain if you haven't seen them, but they were an essential part of our beautiful trees. Here's a description I found on Reddit that explains them well.

Growing up in the 50s and 60s, there were two types of "tinsel" (we called them "icicles"), the crinkly kind that was metallic, and the plastic kind that was coated with shiny silver. The crinkly kind, which I assume was the lead type, were a tad heavier so they hung straight, while the wispy plastic type was shinier and might fly around a bit. I remember once the static electricity caused them to sway when I walked right near the tree. You had to put these on one strand at a time, which was tedious. Taking them off was also an issue, you could never get all of them off. Both types seemed to fade in popularity and garland tinsel became more common by the 80s. As artificial trees became more common, "icicles" became less practical, and even garland seemed to fall out of favor. "Icicles" looked best on an open-style Balsam Fir type of tree, and not so good on fuller trees like a Scotch Pine and Douglas Fir.

Even our family became less enthusiastic about icicles when the lead kind was replaced by the plastic, which we considered a very inferior substitute. Not the same thing at all! We did (usually) wash our hands after handling the lead....

I haven't mentioned music, which was always an important part of the season. Everyone knew the standard Christmas carols back then, and just as with the displays, Silent Night, O Little Town of Bethlehem, and O Come, All Ye Faithful mingled happily with Jingle Bells and Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. We sang at home, we sang in school, we sang at community events. Instead of a solitary volunteer manning a red kettle and ringing an annoying bell, the Salvation Army band treated passersby to carols in excellent brass arrangements. And of course we played our favorite Christmas records while decorating our tree. One of my favorites was Sing We Now of Christmas, with the Harry Simeone Chorale. Although the album cover featured on this YouTube playlist is different, it has the exact songs from our record, and I was thrilled to discover it.

I haven't mentioned music, which was always an important part of the season. Everyone knew the standard Christmas carols back then, and just as with the displays, Silent Night, O Little Town of Bethlehem, and O Come, All Ye Faithful mingled happily with Jingle Bells and Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. We sang at home, we sang in school, we sang at community events. Instead of a solitary volunteer manning a red kettle and ringing an annoying bell, the Salvation Army band treated passersby to carols in excellent brass arrangements. And of course we played our favorite Christmas records while decorating our tree. One of my favorites was Sing We Now of Christmas, with the Harry Simeone Chorale. Although the album cover featured on this YouTube playlist is different, it has the exact songs from our record, and I was thrilled to discover it.

During my young childhood, my family went reasonably regularly to church—a small Dutch Reformed church in tiny Scotia, New York. We did not, however, go to church on Christmas. Christmas Eve and Christmas morning were strictly family time.

Christmas Eve. What do I remember about Christmas Eve? Chiefly that my father always read "A Night Before Christmas" (aka "A Visit from St. Nicholas") just before we children went to bed. My parents stayed up late wrapping and assembling gifts, but for me it was all about anticipation. Back then, Christmas was not even thought of (except by those needing to mail overseas packages) before Santa appeared at the end of the Macy's Thanksgiving Day parade, and the month between then and Christmas seemed to me to stretch half a year. Since then, that time period has somehow shrunk to about half a week, even though the "Christmas season" now starts before Hallowe'en.

In my earliest years, we did not have a fireplace, and hung our stockings on our bedroom doorknobs. Somehow, Santa managed without a chimney.... When we moved to a house with fireplaces, the stockings, as I recall, still didn't hang in front of them. You see, we children were allowed to wake up very early and open our stockings; there was some lower limit to the hour, but it was early enough to please us and late enough to give our parents some much-need additional sleep. But we were not allowed to peek at the Christmas tree—so our stockings were hung on an upstairs railing.

I don't know when the gift inflation started, though it is undeniable. Our stockings were rather small—I remember mine being one of my father's old hiking boot socks—and did not hold a lot, but I don't ever remember being disappointed. (Oh yes; there was one year that I was. At one point my mother, in a bit of exasperation at my never-ending Christmas wish list, exclaimed, "You want the world with a string around it!" So I put that on my list. Lo and behold, in my stocking was a small bank in the shape of a globe, and my parents had attached a string to it. Today, I recognize it as a clever joke, but at the time I was bitterly disappointed that Santa had so misunderstood my request.) In addition to small toys and candy, in the toes of our stockings were always a small coin and a tangerine.

Our own children had huge stockings, hand knit by Porter's mother; they were always stuffed full, and the stocking gifts even spilled over onto the floor. Part of this was no doubt because we always had guests with us for Christmas, and everyone wanted to be Santa. Part was because societal expectations had greatly increased. I was aware of the inflationary pressure, and knew it was dangerous, but had very limited success in fighting it.

On Christmas morning, after we children had opened our stockings and spent some time playing with the toys inside, we were allowed to invade our parents' bedroom and show them our treasures, bringing their own stockings to them.

Next on the agenda was breakfast. I don't recall anything particularly special about Christmas breakfast, only that our parents took an unconscionable long time drinking their coffee! Eventually we persuaded them to finish their drinks in the living room, where the tree was. What a wonder! If there weren't as many presents there as our own children experienced, it certainly seemed an abundance to me. Especially after the family grew to six people. One thing I think we did better with our own children was our practice of opening only one gift at a time, so that everyone could enjoy everything. When I was growing up, my father often passed out gifts to multiple people simultaneously, so sometimes we missed seeing other people opening their presents. It did keep the event from lasting all day, however.

The rest of the day was glorious, as we relaxed and enjoyed all our gifts. Except, of course, for my mother, who spent time fixing Christmas dinner. Unlike Thanksgiving and Easter, the menu wasn't fixed: sometimes turkey, sometimes ham, often roast beef, but always something special.

I didn't discover until much later the joys of being in a church that celebrates the Church Year, where Christmas is not a day but a whole season, of 12 days—until Epiphany. I had happily sung, "The Twelve Days of Christmas" all my life without ever thinking about what that meant. So in our family the Christmas tree usually came down around New Year's Day. Nonetheless, for us children the holiday lasted nearly 12 days, as any time we had off from school was a holiday to us.

And that's a look at the year's holidays as I remember them from my youth. I hope some of you have enjoyed this look into the past as much as I did recalling it.

Permalink | Read 2759 times | Comments (2)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Glimpses of the Past: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

There are a lot of things about the good ol' days that I don't miss—smoking on airplanes is at the top of the list—but recently I was gloriously reminded of one of the benefits that we took for granted at the time: good showers.

I don't think anyone born after 1990 has any idea what a good shower feels like. For almost 25 years it has taken me twice as long as previously to take a shower, because the flow from today's emasculated nozzles is so weak. Maybe if you've stood under a waterfall, or a tropical rainstorm, you have an idea of the joy of a shower free from unnecessary regulation, but it's pure bliss after all this wimpy stuff, let me tell you.

As I stood under the shower, the thought crossed my mind: I know President Trump has a lot of more important things to think about, but I sure wish he'd get rid of the shower head restrictions.

I thought it was just a useless wish. But like my similar dreams that companies would get rid of the junk that fills much of our food, or that someone would take seriously the catastrophic rise in allergies, autism, ADHD, and other afflictions that have replaced measles, mumps, and chicken pox as parental concerns. But at last, we as a country are attempting to address those and other long-time concerns of mine, so I though maybe shower heads had a chance.

Lo and behold, today I learned that President Trump has already rescinded—not the original 1992 regulation of showerheads, which I would have preferred, but at least the subsequent re-interpretations of the rules that were considerably more onerous. I'll celebrate victories when I see them.

There are many ways to conserve resources. One size fits all rarely works well. I'll take shorter, more powerful showers; you're welcome to take longer, wimpier ones.

Maybe it's time to stimulate the economy by buying new showerheads. As long as they're made in America.

Make showers great again!

Permalink | Read 843 times | Comments (0)

Category Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Conservationist Living: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Glimpses of the Past: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]