Since 2010 I have kept a list of the books I've read each year. It began as a New Year's resolution, when I realized that although I was still reading a great deal, the percentage of books included in that reading had declined considerably. In the spirit of "what gets measured, gets done," that resolution was highly successful, and I've kept up the practice of logging my books because I still find it useful.

Last year was my best year ever (108 books read), and this year is on track to be good as well (67 by the end of August, which was ahead of last year's pace).

And then came September.

After a steady reading diet each month from January to August (6, 15, 11, 10, 7, 2, 9, and 7 books), I completed zero (0) books in September. In my 10 years of keeping track, that has only happened once before, in November 2011.

So what did I do in September, if I couldn't even finish one book?

Oh, yeah. We prepared for a hurricane. In the end, it didn't hit us, for which I'm exceedingly grateful, but for a long time it looked as if it would, and the preparation is largely the same whether the hurricane hits or not. And Porter was distracted and out of town until the threats became truly serious, because of his father's death and his subsequent executor duties.

Then we spent three weeks in Switzerland and Rome, where we played with grandchildren and hiked and travelled and visited museums from morning till night.

I could have made a better showing in September if I had thought about it. Some of my favorite times were sitting on the porch swing, reading side by side with our granddaughter, who turned from a self-described non-reader into a confirmed bookworm practically overnight while we were there. I could have been sharing her A to Z Mysteries as she blew through them. Or I could have been reading the new-to-me Life of Fred books that I noticed too late on their shelves. Instead, I tackled a longer and more challenging book: Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray. I should have known I'd end up needing to borrow it and bring it home for completion.

Plus, I have plenty of fairly short books on my Kindle that I could have completed on one of our transatlantic flights. If I'd had a new Brother Cadfael book, I probably would have. Instead, I did puzzles, watched cooking shows, enjoyed a movie about J.R.R. Tolkien (that's another post), and slept.

There are no real excuses for having left September a blank in my reading record. As with many things in life, if I'd put my mind to it, I could have done better. But neither are there regrets. We had an exciting and fulfilling September, and October is another month!

The Message: The Bible in Contemporary Language by Eugene H. Peterson (Navpress, 2002)

The Message: The Bible in Contemporary Language by Eugene H. Peterson (Navpress, 2002)

It's my habit to read through the Bible at a rate of approximately once per year. My last cycle, however, took twice that long, thanks to the version I chose to read. I like to switch up versions, both for the variety and for the slightly different perspectives each brings. This time I chose the very popular The Message, which, as its Wikipedia article notes, "is a highly idiomatic translation, using contemporary slang from the US rather than a more neutral International English, and it falls on the extreme dynamic end of the dynamic and formal equivalence spectrum." In other words, more a paraphrase than a translation.

I'm glad I read it, and I'm sure The Message has been helpful to many, but for me the effort was like slogging through mud. This is the Bible with all the poetry, beauty, and life sucked out of it—not to mention that "contemporary slang" sounds dated the moment it hits print. In the Wikipedia article you can see how Peterson's interpretation of a couple of popular passages stands up against both the King James and the New International translations.

Did I say The Message is a paraphrase rather than a translation? More than that, it's a sermon from beginning to end. Not that I should have been surprised, since Eugene Peterson was a pastor, and the book arose from a lifetime of crafting Bibilical texts into sermons.

Let's just say that I'm glad I have a pastor who occasionally speaks over my head and expects me to rise to the challenge. Peterson's efforts feel condescending and often made me wince.

Dorothy L. Sayers wrote,

The Christian faith is the most exciting drama that ever staggered the imagination of man. ... We may call that doctrine exhilarating or we may call it devastating; we may call it revelation or we may call it rubbish; but if we call it dull, then words have no meaning at all.

The greatest crime of The Message is that it makes the whole Biblical epic sound dull—and like a made-up sermon illustration rather than the messy record of real, historical people that it is.

My apologies to those who find The Message inspiring and exciting. From all I've heard of Eugene Peterson, he was an amazing person, pastor, and scholar. I'm sure his books, including The Message, have been helpful to many. Tastes differ, and I'm thankful we have such a variety of resources available to us.

But for my next cycle, I'm going with the good ol' Revised Standard Version (RSV). Not the new one (NRSV), which also makes me wince, but the version of the book presented to me by "the Church School of the First Reformed Church of Scotia, New York, June 4, 1961." Well, technically, not that book, since most of my reading is done through YouVersion's Bible App. But that version. It's clean, it's poetic, and it should be a good palate cleanser. We'll see if I still feel that way after a year.

The life of a Transportation Security Administration inspector is not an easy one.

The life of a Transportation Security Administration inspector is not an easy one.

I had packed my suitcase efficiently and well, everything neat and tidy and protected as much as reasonable from potential damage. It was full, closed, and ready to go.

Then, my eyes roving over the bookshelves, I discovered that I had left something out: my Ovomaltine spread. (It's sort of like Biscoff cookie butter, but crunchy, malted chocolate.) Fortunately, Porter had plenty of room in his suitcase, and was planning to fill it up with our bags of dirty clothes.

So I wrapped the (glass) jar in plastic wrap, inserted it into a plastic bag, then another plastic bag, and then wrapped that in a dirty shirt. And another dirty shirt. and a pair of dirty pants. And then placed the whole bundle amongst the rest of the laundry in the dirty-clothes bag. This, I was sure, would keep the precious contents intact during the long journey from Switzerland to Orlando.

Intact—but not, as it turned out, unmolested.

My suitcase with its varied contents apparently set off no alarm bells for the security inspectors, but Porter's was selected for special treatment in New York City. Those poor TSA inspectors dug through our dirty clothes bag and unwrapped all those smelly shirts and plastic bags to get to the gold. At least the seal on the jar was unbroken; they didn't bother to taste it.

Thank you for your service. It's a tough job, but somebody has to do it.

What do you do when you're hiking along in Switzerland and a big Bernese Mountain dog runs up to you, leans against your leg, and sits on your foot, stopping all forward motion?

Then rolls over, exposing a furry belly and pleading eyes?

And you're allergic to dogs?

You give thanks that he's not a cat, and give him a good tummy rub using one hand only, promising yourself you won't touch your face until you get home and can wash.

Because who can resist such trusting love?

Ramblings inspired by a glass of milk:

America, the land of Liberty. New Hampshire, the state with the motto, Live Free or Die. Sometimes I wonder what our Founders would think of our current willingness, even eagerness, to give up essential freedoms for (supposed) safety. But then I realize that people are much the same in every generation, so I'm sure they had to deal with plenty of the same kind of opposition.

Am I going to complain about the current attacks on our Second Amendment? Not now, even though I—with a lifelong dislike of guns—find the attempts to disarm American citizens appalling and frightening.

Not this time. Right now I'm standing up, as I have before, for the freedom to enjoy flavorful foods.

I insist that one culprit in our "obesity crisis" is that Americans are unconsciously craving the flavor of normal, healthy food. Food such as the "farm milk" we drink when we are in Switzerland: fresh from the cow, unpasteurized, unhomogenized, just real milk. Real milk that bears only a superficial resemblance to that of the same name purchased in an American grocery store.

At home, I love milk, and drink a lot of it. But I can only drink skim; whole milk sticks in my throat. Except in the form of hot chocolate, which is best with whole milk, even in America. In Switzerland, farm-fresh whole milk is absolutely delicious without any chocolate at all. (Granted, with a piece of dark Toblerone on the side, it is even better.)

There's no comparison between "real food" and that which comes from the average grocery store. Not only is grocery store food highly processed, but it is also deliberately homogeneous, so that there's no variation in flavor—milk is milk, orange juice is orange juice, apple juice is apple juice, chicken is chicken—instead of celebrating and enjoying nature's bountiful variety.

Don't get me wrong: there's a lot of benefit that comes from our mass-produced food, including lower prices. It is, indeed, what they call a First World problem. My objection is not to the availability of such food, but that it is crowding out the small, the local, the variety, the food of tremendous flavors. Worse, the awesome food—food that was plentiful as recently as 30 years ago—is now often illegal in America.

As with many roads to hell, this one is paved with good intentions. Safety is not the only issue—profit is another, as is the fickle American public—and safe food is important. But our approach to safe food reminds me of that old Chinese proverb, Do not remove a fly from your friend's head with a hatchet.

Promising, practical ... and, as with so many applications of massive data collection and analysis, maybe a little perturbing. This post is primarily for the materials scientist in the family, but it should be interesting to anyone.

Scientists at MIT and Berkeley, using Artificial Intelligence algorithms to pore over abstracts from papers related to materials science, have successfully predicted scientific discoveries.

Researchers from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory used an algorithm called Word2Vec sift through scientific papers for connections humans had missed. Their algorithm then spit out predictions for possible thermoelectric materials. ... The algorithm didn’t know the definition of thermoelectric, though. It received no training in materials science. Using only word associations, the algorithm was able to provide candidates for future thermoelectric materials.

Using just the words found in scientific abstracts, the algorithm was able to understand concepts such as the periodic table and the chemical structure of molecules. The algorithm linked words that were found close together, creating vectors of related words that helped define concepts. In some cases, words were linked to thermoelectric concepts but had never been written about as thermoelectric in any abstract they surveyed. This gap in knowledge is hard to catch with a human eye, but easy for an algorithm to spot.

In one experiment, researchers analyzed only papers published before 2009 and were able to predict one of the best modern-day thermoelectric materials four years before it was discovered in 2012.

This new application of machine learning goes beyond materials science. Because it’s not trained on a specific scientific dataset, you could easily apply it to other disciplines, retraining it on literature of whatever subject you wanted.

Here's an article from MIT that's a bit more technical.

MIT and Berkeley may be doing this particular research, but anyone want to guess where the Word2vec algorithm was developed?

Google.

Recasting the Past: The Middle Ages in Young Adult Literature by Rebecca Barnhouse (Boynton/Cook, 2000)

Recasting the Past: The Middle Ages in Young Adult Literature by Rebecca Barnhouse (Boynton/Cook, 2000)

This was another book from my son-in-law's wish list that I found intriguing. It turned out to be both disappointing and enlightening.

The disappointment was my own fault: The stated purpose of the book is "to provide teachers, librarians, and scholars of adolescent literature with a discussion of fiction set in the Middle Ages," so I should not have been surprised that the author talks like an educationist. Neither should I have been surprised (though I was) that the books she analyzes are all very modern. It reminds me of the fifth grade teacher who required that during their "free reading time," her students read only books from the Sunshine State Young Readers Awards list. This, she assured me, was because she wanted to make sure the children were reading quality books. Once I discovered that even to be nominated for that list a book had to be fiction and published withing the last three years, I knew why I was far less than impressed with the selection. I suppose modern authors need some support, but inflicting their works—to the exclusion of all others—on helpless students is even more unfair than forcing the students to eat school lunches.

This teacher-orientation and modern-author bias of Recasting the Past got my reading off on the wrong foot, but I was able to get over it because there really is some good information here. I've long known that much historical fiction, particularly for some reason that favored by schools (and popular movies), plays fast and loose with the facts. I figured the blame mainly fell on lazy authors, who had a story to tell and liked the idea of fitting it into an historical time period, but preferred to make the time fit the story rather than the other way around. Barnhouse opened my eyes to an entirely different source for the problem.

Although the author does not acknowledge this, I'm convinced that the base culprit is that there is such as thing as "young adult fiction." Why there should be is beyond my ken. Anyone who is mature enough to handle the subjects dealt with in these books—which include torture, religious doubts, and sexual activity—should be offended by dumbed-down reading levels and the assumption that everyone of a certain age must be interested in the same things.

Be that as it may, these are aimed at a young adult audience, and it shows. First and worst, the authors are apparently viewing their stories primarily as vehicles for teaching, and teaching 21st century values more than teaching history.

One such value is literacy. Barnhouse notes that much historical fiction aimed at schoolchildren is anachronistic in its attitude towards reading, writing, and book learning. No doubt they want to encourage the same in their modern readers, but it is wrong to give the impression that back then books were considered the key to knowledge, ignoring the practical ways knowledge was passed on in those times.

Modern authors also seem uncomfortable with allowing their young readers to experience attitudes not in line with 21st century standards. The young protagonists must be models of tolerance and diversity as defined by modern educationists; if anything negative is said about Jews, for example, it must come from the mouth of a character that the readers are not likely to like or respect. In a similarly unrealistic approach, Jews, Muslims, and generally anyone-but-Christians are treated by authors of much young adult fiction as paragons of virtue, instead of as human beings.

Barnhouse touches on other subjects, including stories that appear to be set in medieval times but actually belong in the Fantasy genre.

The primary use of his short book is for developing some tools for recognizing anachronism in so-called young adult fiction. Perhaps the most important of these tools is simply being aware of the problem.

Just two short quotes this time, emphasis mine:

The words "Middle Ages" imply a time between two eras, the Roman Empire and the rebirth of Roman culture in the Italian Renaissance. However, tell a twelfth-century Parisian scholar like Peter Abelard that Roman learning is dead and you'll get a surprised look—that is, if you can pry him away from his study of Greek and Roman historians and philosophers. Abelard and his contemporaries used the word modern to describe themselves. The big lie perpetrated by the Renaissance Italians, who said everything was dark and barbaric until they reinvented Rome, shows how little they knew about the transmission of thought, culture, and learning in the medieval period. While it's true that the vast majority of people didn't participate in all of this learning, neither did the majority of Romans. (Introduction, p xiii)

Well-told modern tales of the Middle Ages abound. ... The writers who research carefully enough to understand the differences between medieval and modern attitudes, between different medieval settings, and between fantasy and history, can help their readers understand a strange and distant culture: the Middle Ages. Writers who create memorable, sympathetic characters who retain authentically medieval values teach their audience more than those who condescend to readers by sanitizing the past. Trusting readers to comprehend cultural differences, presenting the Middle Ages accurately, and telling a good story results in compelling historical fiction, fiction that, like medieval literature in its ideal form, teaches as it delights. (p 86)

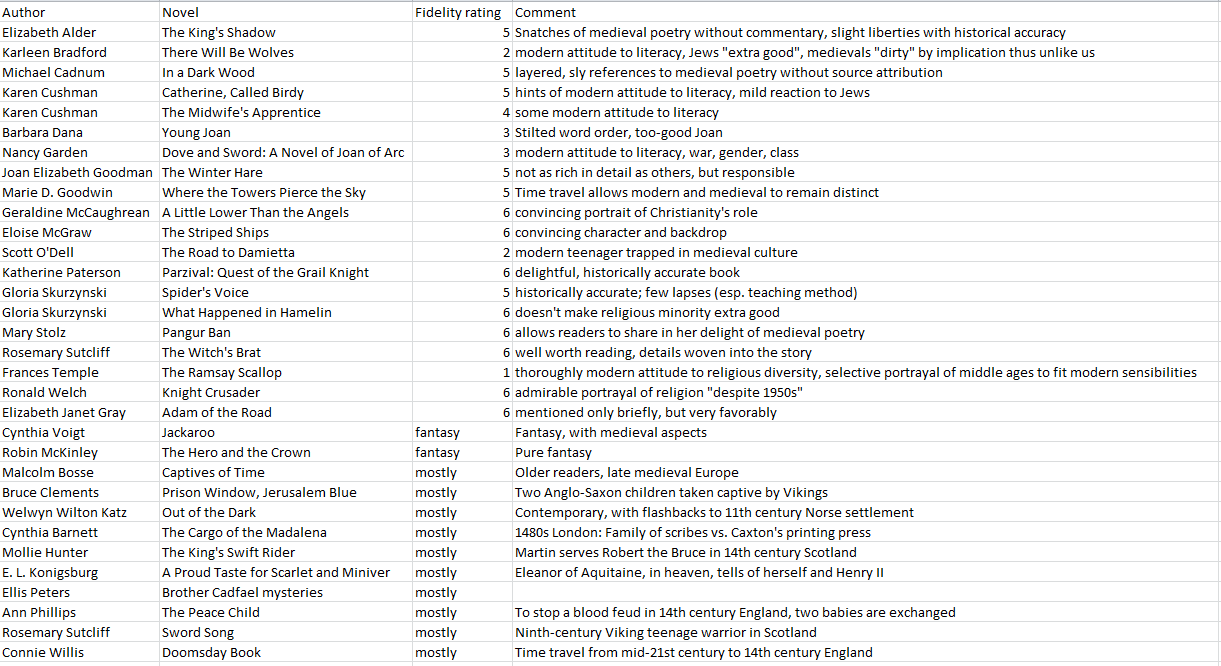

UPDATE 11/5/19 Here's a table from Stephan, summarizing the book's evaluations. Click to enlarge.

Stephan says, What might be confusing about the table is the multiple use of the comments column. The first books with a fidelity rating > 0 come with comments that summarize very briefly Mrs Barnhouse‘s critique; those with a rating = 0 with a „fantasy level“ comment; and the rest with a summary.

I posted the following back in 2011, and its message is just as vital today. Unfortunately, the link to the Occasional CEO article no longer works. I'm hoping that Eric, who occasionally stops by here, will provide the correct information—at which point I'll fix the link.

Educators, please don't miss this post on innovation from the Occasional CEO.

Children in America used to want to become cowboys and Indians, doctors and firemen, astronauts and acrobats. Now they want to become entrepreneurs and innovators. They are told they must change the world, often before they enter it.

But 90% of the population should not become innovators.

It’s not because they can’t do it well, though that’s possible too. It’s just that innovation can cause great damage to the things we love. To the guy making the fries at McDonalds or the pumpkin spice latte at Starbucks: Don’t innovate. To the person building the next lot of iPhones from which I’ll be purchasing one: Please don’t innovate. To my tax accountant: Do Not innovate. The mechanic fixing my car. The pilot flying my plane. To the fine people at Apple: For goodness sake, stop sending me updates and new operating systems. I hate em. Just when I get everything the way I like, you innovate me into something that costs me two hours at the Apple Bar. Where, incidentally, I want zero innovation from your hip kids in blue shirts. Just follow the FAQs and fix my iPad.

When we complain that schools are not teaching our kids to innovate, I say: Bravo! People who can innovate will always find ways to innovate, while most of the rest of us need a serious tutorial in how to follow directions. Show up on time. Do our jobs. That’s not something that comes naturally for many human beings.

There’s nothing less intelligent or inferior about people who practice consistency. Consistency takes extraordinary talent, just like innovation. ... We have made innovation glamorous and consistency somehow mundane and less worthwhile. That’s our fault, not the fault of talented people whose consistency, attention to order, willingness to show up all the time and insistence on a little good ol' tradition improves our lives.

Here endeth the lesson; the following is my editorial comment:

Children do not need to be taught to be innovators and inventors. They need to be taught the facts and skills that will become materials and the tools with which they can innovate, practice consistency, or both. Then they need freedom and time and opportunities to learn to use those tools effectively.

Permalink | Read 1374 times | Comments (1)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

There is something in the very presence and actuality of a thing to make one able to bear it; but a man may weaken himself for bearing what God intends him to bear, by trying to bear what God does not intend him to bear.... When we do not know, then what he lays upon us is not to know, and to be content not to know.

— George MacDonald, "What's Mine's Mine."

Waiting for Dorian is like being stalked by a tortoise. A slow tortoise.

Permalink | Read 1857 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

On a whim—or more accurately, a teaser from my sister-in-law—I put the show Rizzoli & Isles on our Netflix list. It's another crime/mystery series, which, if you consider our Netflix history, you might think is 90% of what interests us. (Including, but not limited to, Rumpole of the Bailey, Poirot, Miss Marple, Tommy and Tuppence, The Bletchley Circle, Death in Paradise, NCIS (multiple versions), Monk, Foyle's War, Castle, Inspector Morse, Inspector Lewis, Endeavour, Grantchester, Murdoch Mysteries, Father Brown, Maigret, Nero Wolfe, Numb3rs, Lord Peter Wimsey....)

The teaser was that one of the Rizzoli & Isles shows—I don't know which one—involves a genealogical investigation. We've been through the first season plus a bit, and haven't yet spotted it, although there is one cringe-worthy episode in which two perfectly-matched DNA samples are proclaimed to be, not identical twins, but half-siblings: one male, one female, no less. I felt as Porter must when he watches movies that play fast and loose with historical facts.

Be that as it may, I plan to keep watching, at least until I get to the genealogy episode, because the characters and the stories are interesting. The usual problems associated with television series apply, at least based on what I've seen so far.

- It is a truth universally acknowledged that a story written by committees of writers, constrained by never knowing how long the series will run and which actors will unexpectedly die or quit along the way, cannot have a story arc that knows its end from its beginning. I know that novelists are often surprised at the directions their stories take as they are being written, but by the time a book gets into the hands of its readers the story is fixed. Not so with long-running TV series. I find this annoying.

- Hollywood producers, directors, writers, and actors are nearly universally liberal (in the sense of the label as it is used these days) in their political, social, and religious views, and this is as evident in Rizzoli & Isles as in most other popular television shows. One does not need to posit ill intent, or a conspiracy to corrupt the population, to acknowledge that these stories are drenched with, steeped in, and pervaded by a world view antithetical to most Christians, most conservatives, and most Americans who live outside of the West Coast, the Northeast, or large cities. It is what it is, and one has a choice: ignore most television and movies altogether, or be alert and aware, noting the sea in which the shows' characters and events swim. The latter is possibly the more rewarding path, but definitely the more dangerous. It's hard to stand in the water without getting wet, and if the frog-and-kettle story isn't actually true to nature, as a metaphor it's spot on.

- The level of graphic violence varies widely from one TV series to another. Rumpole, for example, is only secondarily about the actual crimes, and not at all graphic; NCIS Los Angeles is about some exceedingly violent and gruesome stories, and makes no attempt to hide the visceral realities from viewers. Rizzoli & Isles, so far, is somewhere between the midpoint and the graphic extreme.

So why am I finding the shows worth watching?

- I'm anticipating the genealogy episode.

- The characters and mysteries are interesting, especially the friendship between the title characters. It reminds me a little of the relationship between the two brothers on Numb3rs: one tough and street-smart, one polymath—but with some twists as well. I'm a sucker for quirky, misunderstood—if nonetheless respected—geniuses, hence my attraction to Numb3rs, Monk, Inspector Lewis, and The Bletchley Circle.

- I like the music (Irish-ish)

The show is set in Boston, and I always enjoy recognizing places and people I'm familiar with. In just the first season (2010) there have been some interesting events.

- References to Whitey Bolger when he was still at large (he wasn't recaptured till 2011)

- A show about killings during the Boston Marathon, three years before the famous bombing in 2013. Interestingly, although the event is clearly the Boston Marathon—e.g. a famous marathon set in Boston, mention of "Heartbreak Hill"—in the show it is called the Massachusetts Marathon, which leads to speculation. Probably the name "Boston Marathon" is copyrighted, and perhaps the organization decided they didn't want their race associated in people's minds with violent death. Oops.

Speaking of television series, don't talk to me about the final episodes of NCIS last season. Not only did we miss them when they aired, but we also missed the opportunity to see them free on the CBS site. Season 16 won't be released to DVD till September 3—and who knows when after that they will be available on Netflix. So—someday, maybe.

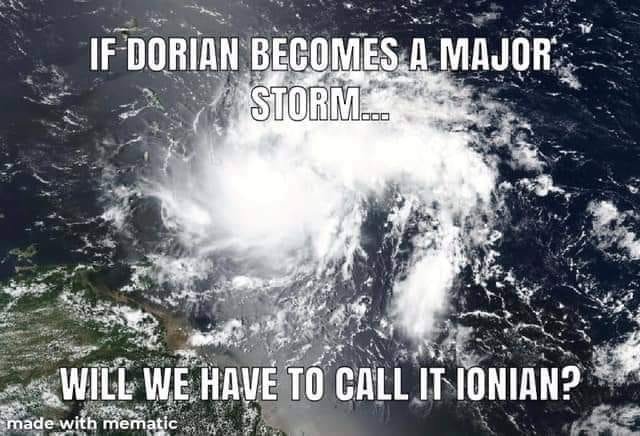

While praying and working with Dorian taking aim right at us, it is impossible to resist some musical jokes about current events. Dorian is my favorite musical mode—I hope I still like it a week from now.

and

Enjoy! Now back to work....

Overall, I'm a big fan of Chick-fil-A. It's the exception to our policy of not eating fast food except when travelling, and even then other fast food restaurants are likely to get our business only when Chick-fil-A isn't available.

Friends who have worked for the company have praised the atmosphere and working conditions. Their workers are friendly and always respond to "thank you" with a cheery "my pleasure!" The restaurants tend to be clean and welcoming. We found that to be true even on our most recent travels along I-95 through Georgia when demand was so high the line snaked through much of the restaurant. Let me repeat that: It was clean—including the restrooms. On I-95. In Georgia.

But none of that is what keeps me coming back.

It's their Spicy Chicken Sandwich. There's nothing else like it.

I've tried spicy chicken sandwiches all up and down the East Coast. We seem to do a lot of Sunday travel—when Chick-fil-A is closed—and when I can, I look for spicy chicken sandwiches. For research, you know.

What we sacrifice for science! Some of the other chicken sandwiches were okay, but none so far has even hinted at being as good as Chick-fil-A's.

The inspiration for this post came from someone else who ate chicken sandwiches for science: Dennis Green reviewed some chicken sandwiches for Business Insider, and he agrees with me.

You know what's better than a chicken sandwich? A spicy chicken sandwich. In the face of uproar over a new chicken sandwich from Popeyes, I could no longer stomach the obviously superior version of the fried-chicken sandwich being left out of the national conversation. ...

I will not sit idly by as this information is suppressed by the mainstream media. Something has to be done. More chicken MUST be eaten. That's why I decided to pit Popeyes' new spicy chicken sandwich against two from Wendy's and Chick-fil-A. ...

Overall, the spicy chicken sandwich from Chick-fil-A hit all the right notes. It was fresh but not too heavy, unlike some of its decadent competitors. Wendy's may have the history, but it hasn't kept up. Popeyes had a good go at it for its recent foray. But for my money, I'm going to Chick-fil-A every time.

I'm with ya', Dennis. From your descriptions, I could have picked the winner without tasting a bite. Both Wendy's and Popeyes serve their chicken sandwiches with mayonnaise? <shudder>.

I can't say I like everything about Chick-fil-A. Their sauces, for example, I find mediocre at best. But you know what? I don't care. Because their spicy chicken is so good anything more than a little ketchup would detract from the experience. Sometimes I even skip the ketchup.

Their Spicy Chicken Biscuit was so good I never dressed it. It's the only thing I've found at Chick-fil-A to rival the Spicy Chicken Sandwich.

But that brings me to something else I don't like about Chick-fil-A: they discontinued their Spicy Chicken Biscuit. What were they thinking?

Our nephew's fiancée has just begun a career in management at Chick-fil-A. I know it will take her a while, ambitious as she may be, to get anywhere near the decision-making level, but I have great hopes: a Chick-fil-A to open in Old Saybrook, Connecticut, and the return of the Spicy Chicken Biscuit.

Are you listening, Cows?

Porter is now the patriarch of our family. His father died last week, at the good age of 92. We are thankful that he did not linger in a nursing home, and that his mind was still his own even as his body deteriorated. His obituary was published in the Hartford Courant of August 22, 2019. Because the Courant charges a shocking price, I'm publishing the longer (and more genealogically satisfying) version here.

William Stoddard Wightman of Old Saybrook, Connecticut died August 15, 2019 at Middlesex Hospital in Middletown. Born February 21, 1927 in Bristol, Connecticut, Bill was the son of Stoddard Elsworth Wightman and Hilma Louise (Lulu) Faulk. He is survived by a son, William Porter Wightman (Linda) of Altamonte Springs, Florida, and a daughter, Prudence Wightman Sloane (Jay) of Salem, Connecticut, as well as three grandchildren, Heather (Jon) Daley, Janet (Stephan) Stücklin, and Spencer Sloane, and ten great-grandchildren, Jonathan, Noah, Faith, Joy, Jeremiah, and Nathaniel Daley, and Joseph, Vivienne, Daniel, and Eleonora Stücklin. He was predeceased by two wives, Alice Davis Porter of Higganum (1952-2001) and Arline Johnson McCahan (2002-2012), one sister, Elinor (Wightman) (Fredrickson) Fisher, and one great-grandson, Isaac Daley.

Bill enlisted in the Navy the day after he turned seventeen and was trained as a medic for the invasion of Japan, but was “saved by the bomb.” After the service he worked as a shad fisherman and helped Ernie Hull build the marina at Saybrook Point. He then went to Mitchell College and the Rhode Island School of Design, getting a degree in textile engineering. He worked thirty years for Albany International designing paper machine clothing. This gave him the opportunity to work abroad in France, Sweden, Holland, Brazil, and South Africa. He retired in South Carolina in 1982, living there until his second marriage in 2002 when he moved to Old Saybrook. He was an avid sailor and proud owner of the Fenwick cottage, the “Maggie P.” In lieu of flowers donations can be made to the U.S. Navy Memorial in Washington.

As our new rector has taught us, we are bold to say,

May he rest in peace and rise in glory!

The school lunchbox is dead in Italy.

The Italian Supreme Court has ruled against parents who want to send lunch to school with their children. Their logic? Not eating the school-provided lunch is "a possible violation of the principles of equality and non-discrimination based on economic circumstances."

Even the United States isn't that crazy—yet—despite pushes in that direction by busybodies experts who worry that food from home might not be "good enough," and school-lunch providers who have a deep financial stake in forcing parents to buy their product.

Parents, naturally, are not happy.

Lorenza, who has two children at a Turin school, told a local TV station she spent more than €2,000 (£1,823) on school meals, more than her monthly salary. "My older daughter was not happy because the quality of the food didn't justify the cost, and also because of the hygiene issues with the canteen. "She would often complain that the cutlery was dirty, that the glasses were not particularly clean, or that there would be hairs on the plates," she said.

As with many news reports, this paragraph does not give enough information for us to know just how outraged we should be. Over what time period did this mother spend $2200 dollars? One month, as implied by the comment that the cost was "more than her monthly salary"? Annually per child? Over the entire school experience of all of her (possibly, though not likely, many) children?

Never mind. It doesn't matter. Even if the meals were totally free (where by "free" we mean paid for by other people, of course), it would still be an outrage.

School lunches may be a necessity for some children, who would otherwise not eat—though I've never been able to answer satisfactorily a friend's question, "Isn't that what SNAP (formerly Food Stamps) and WIC programs are all about? Why do we also need free school lunches?"

School lunches are certainly a convenience for busy parents—though there is no reason why a child of school age shouldn't be able to pack his own lunch.

But there was never any doubt in my mind that my own packed lunch was vastly superior to what was offered in the school cafeteria, and apparently our children thought so, too. Even if they often traded their carrot sticks to other children for cookies—at least some child was eating healthful food. I'm reminded of one family I know who qualified for free meals for their children. The children gave it a try, determined that the food at home was better tasting, more nutritious, and even more plentiful—and wisely opted out. At least here they had that option.

More to the point: whatever the Italian Supreme Court may say, being able to feed our children as we think best is a basic, human, family right—right up there with being able to birth, educate, and otherwise rear our children as we think best. As all totalitarian governments know, once you come between parents and their children, most other freedoms become meaningless.

For those families who cannot or will not handle these responsibilities on their own, we rightly make assistance available. That's called charity. But forcing that "assistance" on those who do not want it? That's called tyranny.

And the "principles of equality" the court found so important? Should we make everyone feed their babies formula because some mothers can't or won't breastfeed? Dumb down the school curriculum to the lowest common denominator? Put every child in daycare because some families need that service? Force every child into public school because some parents can't or won't provide private or home education? Make every woman give birth in a hospital because some babies need a doctor's care? Ban unpasteurized milk, orange juice, and cider because not everyone has access to safe sources of these delicious drinks? Forbid handmade clothing because not every mother can sew? Put handicapping weights on the feet of the best dancers to eliminate their advantage over the klutzes?

Oh, wait. Objects in the mirror are closer than they appear.

Smoke on the Mountain: An Interpretation of the Ten Commandments by Joy Davidman (The Westminster Press, 1953)

Smoke on the Mountain: An Interpretation of the Ten Commandments by Joy Davidman (The Westminster Press, 1953)

I recently re-read Joy Davidman's book because it seemed logical to include in my C. S. Lewis retrospective. How long ago was my previous reading I can only guess, but it's likely two decades or more.

The first time around, I remember being quite impressed by Davidman's take on the Ten Commandments; this time, less so. It's still a book worth reading, but perhaps two decades further on has made her examples and emphasis seem more dated. Her analysis is still pretty good, however. Basic human nature doesn't change—and neither do the Commandments.

The one thing that bothers me most is certainly very minor in the scheme of the book, but it comes up over and over again. Not in anything directly related to her arguments, but in her assumptions about society: that is, that one of the biggest problems of this world, and a concern of all intelligent people, is overpopulation. I think my children don't understand quite how intense the pressure was in my generation to have no more than two children. I'm very glad that has now eased—but the attitude still rankles when I run into it.

Maugre all that, there were plenty of quotes worth extracting. Remember that Davidman was writing in the early 1950's, and reflect how à propos they still are.

The articulate, the leaders of opinion, the policy makers, all those who set the tone of our society, seem for the most part to be frightened men. (p 18)

Despite her fears of overpopulation, Davidman has a pretty good take on much of what's wrong with family life today.

Everybody today ... will agree that that family life is indispensable to human health and happiness. Yet we find ourselves accepting conditions that make war on the family. The lands behind the Iron Curtain deliberately weaken family ties in their schools, lest loyalty to parents should conflict with devotion to the sacred State. Our own country tries to keep the home fires burning with verbal sentiment about Mom, but meanwhile forces Mom to leave the hearth fire untended while she tends the factory machine. A century ago, American houses were twelve-room affairs designed to hold grandparents, and maiden aunts, and uncles, as well as parents and children; today they are usually cramped little flats and cottages, and we feel lucky to get those. We can hardly do much about honoring Father and Mother if there's no room for them in the inn. (pp 63-64)

I will add that the Iron Curtain may have fallen, but schools are doing no less to weaken family ties, and today they've been joined by a host of other assailants, from governmental policies to music, movies, and television.

Every age has its professional apologists, and ours are working hard to convince us that our worst sins are virtues. A mother forced to take a job needs a crèche [daycare] for her baby, admitted—but that does not justify the false comforters who tell us a crèche is better than a mother. An overcrowded school must pick up its pupils in large handfuls all of an age, and pass them along without paying attention to their individual abilities—yet this hardly warrants the current theory that children ought to be herded in age groups, as if we gave birth to them in litters! The cooped-up small families of cities are likely to develop unhealthy tensions, as we all know—need we, therefore, swallow the fashionable psychological doctrine that it's natural for all sons to hate their fathers? Were it really true that sons and fathers are natural enemies, how could mankind ever have dreamed of such a thing as the Fatherhood of God? (p 65, emphasis mine)

Through such apologies, and our own mental laziness, we are in danger of accepting without question some very queer distortions of human life. Already our generations are being walled off from each other: teenagers flock together deaf to all language but their own, young couples automatically drop their unmarried friends, whole magazines address themselves to age groups such as the seventeens or the young matrons or the "older executive type." Vast numbers of people think it is "natural" to hate your in-laws, "immature" to ask your parents for advice after your marriage, "abnormal" to value the companionship of anyone much older or younger than yourself. (pp 65-66)

Our modern cities have created a society in which children are in the way. They are physically in the way, and therefore we find them in the way emotionally too. There are many who do not want them at all, like the girl who recently told this writer that a civilized woman can "realize her creative impulses through self-expression" without needing anything so dirty as a baby! Even those who do want them are sometimes rather shame-faced about it; pregnancy, once something in which a woman gloried, is now treated as a disfigurement to be concealed as long as possible; and giving suck, the greatest joy and greatest need of both mother and child, is quite out of fashion among us. "I'm not a cow!" some American women will remark scornfully, as if it were preferable to be a fish. (pp 66-67)

Worse yet, perhaps, is the taming process we are forced to put our children through in order to keep them alive at all in city streets and city flats. In their infancy we must curb their play, and force adult cautions and restraints on them too soon; in their adolescence, on the other hand, we must bend all our efforts to keep them children at an age when our ancestors would have recognized them as grown men and women ready to found families. Our objection to child labor is admirable when it prevents the exploitation of babies in sweatshops, but not when it keeps vigorous young men and women frittering away their energies on meaningless school courses and still more meaningless amusements. (p 67)

It is gratifying to know that in our time pregnancy, nursing, and rearing independent children have been enjoying a comeback, but the gains are yet small and the opposition still great.

Let us remind the innumerable Americans who don't seem to know it that begetting and rearing a family are far more real and rewarding than making and spending money. (p 69, emphasis mine)

"Honor thy father and thy mother" is not the only Commandment on which Davidman expounds—it's just the one for which I found the most interesting excerpts. Here's one for "Thou shalt not steal," followed by one each for "Thou shalt not bear false witness," and "Thou shalt not covet."

Our society, in some respects, is a vast confidence game. Even our money sometimes becomes a swindle; no crueler form of theft was ever devised than an inflation, and since the value of paper money depends on that doubtful commodity, faith in the Government, it is hard to see how all present currencies can help inflating. Those who remember the German inflation of the 1920's know what happens, in such cases, to trusting old people living on pensions and savings. (p 105, emphasis mine)

Sadly, even our professional economists seem to have forgotten the horrors of inflation. I only need to look back as far as the 1970's to fear inflation—and we were in a good position then, with salaries that inflated along with the dollar. Inflation is very attractive to governments and other debtors; it rewards spending beyond our means, promotes consumerism, and punishes thrift and contentment. Unfortunately, for governments and those crippled by debt, inflation looks like a promising get-rich-quick scheme. We all know where those lead.

Perhaps what unsettles the modern mind most is its despair of ever knowing truth and the conflicting and untrustworthy and very dusty answers we get in our daily life. There are people who believe that not only are there no truths, but there are not even facts—all is a matter of "subjective values." Whatever the merits of this as a philosophy, its practical use is often as a method of evasion and rationalization. ... The denial that truth exists is a good beginning for habitual lying. And if we start confessing our habitual lies, shall we ever be done? There are the lies of gossip, public and private, which make haters out of us; the lies of advertising and salesmanship, which make money out of us; the lies of politicians, who make power out of us. And the lies of the sort of journalist who manufactures a daily omniscience out of the teletype machine and the Encyclopaedia Britannica! And the lies of a professional patriot who assures us that our cause is so just that it doesn't matter what injustice we commit in its name! Two hundred years ago Dr. Johnson wrote:

"Among the calamities of war may be justly numbered the diminution of the love of truth by the falsehoods which interest dictates and credulity encourages. A peace will equally leave the warrior and the relater of wars destitute of employment; and I know not whether more is to be dreaded from streets filled with soldiers accustomed to plunder or from garrets filled with scribblers accustomed to lie."

The observation still holds good, except that the scribblers no longer live in garrets. The pay is bigger nowadays—but then, so are the lies. (p 111, emphasis mine)

Seeing God face to face is our goal; the pleasures of life, and even life itself, are the means to it. Therefore the milk and honey and corn and wine and soft chairs and fine houses and swift automobiles—all those pleasant things!—exist primarily as a kind of currency of love; a means whereby men can exchange love with one another and thus become capable of the love of God. ... We value such things not only for their pleasantness, but also because we can give them away and give our love with them; or else because, in receiving them, we receive others' love for us as a baby at the breast sucks his mother's love with her milk. (p 122, emphasis mine)

What a delightful view of the giving and receiving of gifts!