Having finished YouVersion's Cell Rule of Optina read-through of the New Testament by Thanksgiving, and planning to start a new chronological plan at the end of the year, I wanted something short to take me through Christmas. I chose Before the Cross: the Life of Jesus, which was billed this way: "This 80 day reading plan takes you through the four Gospels, in chronological order, walking through the life of Jesus from His birth to His ascension into Heaven." That's almost true, though they did leave out some of the less action-oriented passages. I easily compressed the 80 days into one month.

I also switched versions of the Bible for this reading. My favorite versions are either the old New International Version or the old Revised Standard Version, neither of which is often accessible in online form. I had been using the English Standard Version on my phone, which is a little modern for me but not bad. This time I decided to try the New King James Version. I'd heard a lot of positive talk about the NKJV, but I was not impressed. I was expecting a reworking of the beautiful-but-outdated King James Version that takes into account all we've learned in the field of Bible scholarship since the early 1600's. Maybe it's not outdated anymore, I don't know—but I do know it's no longer beautiful. Why produce yet another Bible stripped of its poetic language? We had plenty of those already.

Now that I've finished the Before the Cross plan, I've committed to another year-long chronological plan. Not the chronological plan I started with; that was a great one, but why not try another one, since there isn't completely agreement on chronology? This is called Reading God's Story: One-Year Chronological Plan, and this time I've chosen to use the Holman Christian Standard Bible.

I'm still gung-ho about the YouVersion system. Granted, most of their reading plans are not what I'm looking for (too short, too slow, too embellished, too disjointed), but I still find what I need. And having it right there, on my phone, easy to access, easy to keep track of—priceless.

I'm not Englebert Humperdinck. I'm not Michael Bolton. But <ahem> last night I sang with the amazing Ashley (Locheed) Tessandori! Don't ask about the venue or the size of the audience, just let me bask in the reflected glory.

Permalink | Read 2176 times | Comments (0)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

My random quotation generator greeted me with this when I turned the computer on this morning:

May no gift be too small to give, nor too simple to receive, which is wrapped in thoughtfulness and tied with love. - L. O. Baird

Merry Christmas to all!

Permalink | Read 2014 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I did some last-minute grocery shopping this morning, realizing that my normal day for that event (Friday) was out of the question this week. Boy am I glad I didn't go later in the day—it was crazy enough as it was.

Before I even put the groceries away I checked my e-mail, which contained a Christmas greeting from Publix, our grocery store. I like it so much I have to share it with you.

Permalink | Read 2149 times | Comments (2)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I know it's Advent, and we're still waiting for Christmas. But that's the header for our Christmas newsletter. This year we revamped our system for Christmas cards, sending more than half of them out by e-mail. I'm concerned that some folks may have gotten lost in the upgrade.

So if you did not receive our Christmas letter, and would like to, please let me know.

Permalink | Read 1978 times | Comments (2)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

1066 and All That: A Memorable History of England by W. C. Sellar and R. J. Yeatman (Barnes and Noble, 1993, original 1931)

It All Started with Columbus: An Improbable Account of American History by Richard Armour (McGraw-Hill, 1953)

Attention teachers and parents: Next time a child whines, "Why do I have to learn history?" you are free to use my answer. "So you will be able to understand why these books are funny."

They are funny, and clever to boot, but without a solid grounding in history, and some literature as well, you're not likely to get the jokes. As poor as my knowledge of history is, I'm confident I know more about British history than most Americans; even so, a good bit of 1066 and All That left me scratching my head.

It went better with It All Started with Columbus, which does the same thing for American history, a subject on which I am still apallingly ignorant but at least savvy enough to get most of the jokes. It doesn't cover as many years, America having less history than England, but unlike the British book, it gets past World War I. Not much past, however. I wonder if anyone's written a sequel to either of the books.

I think Armour was the better writer, but that may just be the influence of my greater familiarity with his subject. Armour pays homage to his inspiration in the book's dedication:

Humbly dedicated, in an attitude of gratitude, to Walter Carruthers Sellar and Robert Julian Yeatman, who wrote the wonderful 1066 and All That

From 1066 and All That:

The Scots (originally Irish, but by now Scotch) were at this time inhabiting Ireland, having driven the Irish (Picts) out of Scotland; while the Picts (originally Scots) were now Irish (living in brackets) and vice versa. It is essential to keep these distinctions clearly in mind (and verce visa).

From It All Started with Columbus:

[Benjamin Franklin] was self-educated, which means that he was too poor to go to school and therefore got a good education.

My 95 by 65 Goal #11 was initially a "to be decided later" walking challenge. Yesterday I decided it was about time I set that up, and determined that it would be fun to aim for the distance between here and our family in New Hampshire. The "crow flies" distance is 1130 miles. Since the middle of 2014 I've been letting my phone keep track of the steps I've taken (walking or running). That's only if I have the phone on me, so the recorded numbers are lower than my actual steps, but quite good enough for this purpose.

The app keeps track of the raw data, but not in a form useful for "walking to New Hampshire," so today I set up a spreadsheet to analyze the data, starting from the beginning of this year, and keep track of my progress as I head for the goal.

SURPRISE! I'm already there! I arrived two days ago.

It blows me away to realize how much I've walked in under a year. I guess small steps do make for great progress over time.

Continuing the trip to "visit" our other grandkids adds 3747 "crow files" miles and involves walking on water. I guess I'd better get going!

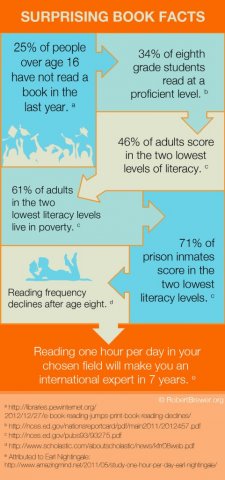

A friend shared this on Facebook. (Click to enlarge; you'll see later why I want to keep it small.)

I'm not criticizing the sharer, nor the original post, because the ideas this image suggests are valid. But I was inspired mostly to comment and to ask questions, beginning with: Where do these facts come from? I'm not going to answer that one yet, because what I found pretty much makes my other comments unnecessary, and I like them, so I'm going to give them first.

- Since approximately two-thirds of high school graduates attend college (and therefore presumably read some books), this implies that the people who don't graduate from high school but later enjoy reading are very rare. Whether or not it's true, it makes sense for the here-and-now, though not in other times and places.

- That forty-two percent of college graduates never touch a book again I find less believable. This is a population that presumably enjoys learning—unless they went to college solely because they bought into the fallacious idea that it would guarantee them high-paying jobs.

- Fifty-seven percent of new books are not read to completion? Hmmm. I suspect that 57% of new books aren't actually worth reading to completion, so I'm not sure this is a bad thing.

- Define "been in a bookstore." I've read 67 books so far this year, but I can't tell you the last time I was in a bookstore. When they closed our local Borders, that pretty much sealed my relationship with Amazon.com. Even before that, the local bookstores almost never had the books I was looking for. Now if they asked me how often I've been in a library in the past five years, that would be an entirely different story.

- Define "buy a book." Does that mean only physical books? If so, it's disingenuous to leave out e-books. Likewise, buying a book is not a particularly lofty goal in my mind (though I've spent a fortune on them); I'm a big fan of libraries. On the other hand, this statistic says that 80% of families did not buy or read a book. So there's another question:

- Define "family." There are about 50 million children in American public elementary and secondary schools, which is more than 15% of the entire population, and a much greater percentage of "families" of even the most generous definition (i.e. including any two or more people living together, with or without children). And it ignores all students in private and home schools, as well as college students. No matter what they do at home, each of these students must have in the last year read not just one but several books (or been read to, for the non-readers). So even stretching the definitions out of all reality, I can't make sense out of the 80% figure.

- And the last one? Reading an hour a day in one field makes you an expert in seven years? I wish! Seven years times 365 days per year is a mere 2,555 hours of reading.

Okay, I've said all that because that's what's currently going around Facebook. But my first attempt at investigation—from squinting at the fine print at the bottom—led me to this page on Robb Brewer's website. There he abjurs "any and all connection" to the statistics in the original graphic, and requests that if people are going to publish it, they use this one instead (again, clicking will enlarge the image):

I didn't check these statistics, because Mr. Brewer clearly did. Except for the last one, which he kept for its feel-good value.

And yes, I had a thousand better things to do than critique a Facebook graphic. OCD takes many forms.

Actually—there really ought to be a word for "daughter's in-laws."

That Phil and Barbara were involved in a protest back in the day doesn't surprise me. But I had no idea they made the New York Times!

Here's the update almost thirty years later.

Permalink | Read 2277 times | Comments (0)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

A friend shared this picture on Facebook. I have no idea where it came from, and it's not very Christmasy, but it sure is clever.

Permalink | Read 1948 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach (W. W. Norton, 2003)

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach (W. W. Norton, 2003)

This was another gift from my library-book-sale-scrounging sister-in-law, who does an amazing job of finding books I like. This one I doubt I'd have picked out on my own, but it was fascinating reading. Best of all, Mary Roach is an excellent writer. I'd reckon not many people could write about such a gruesome topic with respect, accuracy, and humor.

The hardest chapter to read was on cannibalism, especially about the consumption in China, "for medicinal purposes," of aborted babies. Wanting to find out if this was true or an anti-Chinese urban legend, the author investigated and was told that it used to be true, but the government had subsequently declared the practice of selling aborted babies illegal. Further investigation revealed, however, that the reason for the ban was so that the government could hold a monopoly on the business....

The chapter on head transplants was nearly as disturbing, and reminded me strongly of C. S. Lewis's That Hideous Strength, which was written in 1945 and shows the influence of early experiments in the field.

The most interesting and informative chapter was on the use of forensic analysis to help determine the cause of an airplane crash. Analysis of remains helps determine if a bomb was involved, and if so where it was placed (how fragmented are the bodies, and what is the pattern of embedded shrapnel?), if the plane was hit by a missile (what parts of the bodies were burned?), and where the plane broke apart (which bodies were clothed, and which nude?). As I suspected, the purpose of all the airplane safety lectures is to help with near-ground crashes. Break up in midair and, as Roach puts it, you've booked your final flight. The kinds of problems that cause a plane to rip apart high in the sky are simply not survivable.

Take-off and landing crashes are potentially survivable 80 to 85 percent of the time. However...

The key word here is "potentially." Meaning that if everything goes the way it went in the FAA-required cabin evacuation simulation, you'll survive. Federal regulations require airplane manufacturers to be able to evacuate all passengers through half of a plane's emergency exits within ninety seconds. Alas, in reality, evacuations rarely happen the way they do in simulations. "If you look at survivable crashes, it's rare that even half the emergency exits open," says [injury analyst Dennis] Shanahan. "Plus, there's a lot of panic and confusion." Shanahan cites the example of a Delta crash in Dallas. "It should have been very survivable. There were very few traumatic injuries. But a lot of people were killed by the fire. They found them stacked up at the emergency exits. Couldn't get them open." Fire is the number one killer in airplane mishaps. It doesn't take much of an impact to explode a fuel tank and set a plane on fire. Passengers die from inhaling searing-hot air and from toxic fumes released by burning upholstery or insulation. They die because their legs are broken from slamming into the seat in front of them and they can't crawl to the exits. They die becajuse passengers don't exit flaming planes in an orderly manner; they stampede and elbow and trample.

The secret to surviving in such a situation? Sitting close to an exit is number two, but the most important, statistically, is to be male. I guess "women and children first" only works on ships, where chivalry has time to overrule our basic survival instinct.

Cadavers are useful for more purposes than people think when they nobly declare, "I want to donate my body to science": from anatomy class, to surgery practice, to automobile safety labs (crash test dummies can only go so far), to research on the most practical and ecological ways of disposing of bodies (intended to inform funerary practices, not murderers seeking to hide evidence). They're also used to analyze the effects of weapons of war, and I include the following for its Swiss reference:

Theodore Kocher, a Swiss professor of surgery and a member of the Swiss army militia (the Swiss prefer not to fight, but they are armed, and with more than little red pocket knife/can openers), spent a year firing Swiss Vetterly rifles into all manner of targets ... with the aim of understanding the mechanisms of wounding from bullets.

And one more, to show the kind of humor with which Ms. Roach lightens this difficult subject.

Our conversation has moved from White's lab to a booth in a nearby Middle Eastern restaurant. My recommendation to you is that you never eat baba ganoush or, for that matter, any soft, glistening gray food item while carrying on a conversation involving monkey brains.

Many thanks to my sister for finding this ray of hope from Oklahoma Wesleyan University after our depressing conversation about the state of higher education, inspired by my Victimizing the Victims post. University preident Dr. Everett Piper's letter has since gone viral, as well it should have, but that won't stop me from adding my voice. The letter is short and well worth reading in its entirety, but I will quote only the final two paragraphs.

Oklahoma Wesleyan is not a “safe place”, but rather, a place to learn: to learn that life isn’t about you, but about others; that the bad feeling you have while listening to a sermon is called guilt; that the way to address it is to repent of everything that’s wrong with you rather than blame others for everything that’s wrong with them. This is a place where you will quickly learn that you need to grow up.

This is not a day care. This is a university.

Would that this kind of sanity would itself go viral.

Pericles, Prince of Tyre

Pericles, Prince of Tyre

While there's no substitute for seeing a play live on stage, as it was intended, I'm thankful for the opportunity provided by the BBC and Netflix to work on my 95 by 65 goal #67, Experience all 37 of Shakespeare's plays (attend, watch, and/or read). Last night we watched their version of Pericles, Prince of Tyre. Back in 2007 we'd seen a reduced version of the play produced by our local Mad Cow Theatre, but it's safe to say we remembered almost nothing. Wikipedia provided a synopsis that helped greatly in following the convoluted tale. Fortunately, the diction and accents were not as difficult as they often are with Shakespeare, because this version included no option for subtitles, which we often find very helpful.

It's not one of the classics, and is suspected of being a collaboration between Shakespeare and a lesser playwright. Nonetheless, Pericles was one of the most interesting plays we've seen so far, largely because of its unfamiliarity. There's another reason why it's not studied in high school—or at least not in our high school days: the play begins with incest, and goes on to attempted rape, prostitution, a hint at lesbianism, kidnapping, attempted murder, and some pretty bawdy lines. Mild for today, but NSFG (not safe for grandchildren)—except, of course, that much of it would fly over their heads, especially without subtitles.

This year we splurged and purchased annual passes to Disney World—for the first time since we moved to Central Florida over 30 years ago. Back then, with two very young children (four and not-yet-two), the reason was to free ourselves from the pressure to drive our kids hard in order not to "waste" any of the very expensive day at the park. What was our excuse this time? Beats me, but we're enjoying it. Porter's retirement frees us to visit the parks on our own schedule, and his annual pass provides free parking. (Mine is a lesser, cheaper version, but what need have we for two parking passes?) When parking is $20, it's a deterrent to casual visits.

All that to say: for a year, we can go to Morocco for dinner. Or China. Or Norway. For our first trip, we chose EPCOT's Marrakesh Restaurant, always one of our favorites. Then we stopped by Japan; we didn't buy anything, but admired a lot. We didn't buy any funnel cakes, either. Pictures bring memories of good times but no additional calories. :) You can click on the images to enlarge the photos, but please don't drool on your keyboards.

Beef brewat rolls, chicken bastilla, Jasmine salad...and bastilla for dessert

Beef brewat rolls, chicken bastilla, Jasmine salad...and bastilla for dessert

The Kids from Nowhere: The Story Behind the Arctic Educational Miracle by George Guthridge (Alaska Northwest Books, 2006)

The Kids from Nowhere: The Story Behind the Arctic Educational Miracle by George Guthridge (Alaska Northwest Books, 2006)

Jaime Escalante in Los Angeles, Marva Collins in Chicago, John Taylor Gatto in New York City, and George Guthridge in Gambell, Alaska, on the tip of Saint Lawrence Island, as remote as it gets: What do they have in common? A lot, it turns out. Each saw potential in children the educational system had given up on, each led those students to levels of academic excellence that would be envied anywhere, and each ran up against the most unbelievable opposition from other teachers, administrators, and the system itself. People who rock institutional boats are not generally well-liked, even if—maybe especially if—their results are outstanding.

In some ways George Guthridge reminds me of Bob Goff: a bit of a loose cannon, initial trouble finding his way in life, an unconventional thinker with an emphasis on action.

(click the image for an interactive version in Google Maps)

Guthridge, along with his wife and two school-aged daughters, moved to a small, isolated Alaskan Native village on an island near Siberia. The school in which they were to teach was troubled, threatened with closure, and expected almost nothing of its students. Teachers rarely lasted more than one year, sometimes less, and tended to give out good grades for any number of non-academic reasons: not wanting to damage the students' self-esteem, to avoid being beaten up, or simply out of laziness. The students were as unmotivated and disruptive as in any inner-city school written off by the educational system.

Out of this, despite very hostile colleagues and administrators determined to stop him, Guthridge created and coached teams for the Future Problem Solving competition, leading these children—to whom nearly nothing had been given academically and from whom even less had been expected—to two astonishing national championships.

More than just another testimony to the high capacity of children for excellence when they are respected and inspired, and to the criminality of a system that thwarts that excellence, The Kids from Nowhere is valuable for the thought processes by which Guthridge and the students learned to solve their problems.

Not until I was on sabbatical, working on a doctorate, did I start to understand what the kids and I had done ... the welding together of two ladders of learning. We married Western culture's syllogistic, abstract, linear thinking to the holistic, nonlinear, realistic reasoning of indigenous culture. The result is a communicator who addresses the world in a new way.

For that reason, and more, I highly recommend this book to any educators, but especially to homeschoolers, many of whom already have a desire to meld different ways of thinking and to look at the world in new ways.

This book was a Christmas gift back in 2013, and I picked it up recently primarily to make progress on 95 by 65 Goal #63 (Read 26 existing but as yet unread books from my bookshelves). I couldn't put it down. Part of my reasoning behind Goal #63 was to read books and then declutter them. But too often after I read them I don't want to get rid of them! This can't just go into the library book sale pile, though I'd be happy to pass it on to a good home—say to a homeschooling daughter?

Oddly enough, I have only three more quotes to add. I wasn't initially planning to review this book, just to read it and check it off of my list.... That's okay, though. You should read the whole story.

"[What can you do to] turn common ideas into original ones?" ... With a flourish I open the box and lift the funnel in triumph. ... "You funnel down the ideas," I say, holding the thing before them like a chalice. ... "Make them smaller. General ideas are almost never original ideas," I tell them. "That's because almost everyone knows general information. ... To have any hope of having original ideas, you have to be very precise. ... In writing, it's the little things that are important, not the general ideas. The same is true for Problem Solving. You funnel down the general to the specific."

So many faculty fear disappointing students that each kid ends up with several Certificates of Achievement. There seems to be little room for anything except success in contemporary education, as if no one fails in the real world. The trashcan outside the gym ends up with most of the certificates.

When Bruce and I review what are supposed to be rough drafts, I am stunned at how much the kids understand about genetic engineering.... The depth of their learning is almost comical, were it not so impressive. Because Bruce and I have made no distinction between the simple and the complex the kids don't either. They accept as second nature concepts that other kids might groan over. [emphasis mine]

At least at the time of publication, all the royalties from The Kids from Nowhere were being donated to build a school in the Himalayas.