Maybe it's social media, maybe it's that those who present the news can't seem to do so without whipping up our fears and our anger, but I'm sensing a deep angst in much of America that doesn't seem to have a rational explanation.

Maybe it's appropriate in a society where the term "hate" has been so devalued that it is pulled out to explain mere difference of opinion, but I'm seeing an entirely irrational, and sadly pervasive, attitude of hatred for ... 2016. One person expressed it this way: I'm going to stay up past midnight on New Year's Eve just so I can watch 2016 die.

Really people? You hate a segment of the calendar? You would rejoice over the loss of 365 days? You are so miserable that you would wipe an entire year out of your life?

I've had some hard times in my 64+ years on this planet. But even the year where I lost both my father and our first-born grandchild, while still reeling from the death of my mother-in-law, a job loss, a traumatic move, and the shock of 9/11—even that year was so loaded with blessings I can't imagine cursing it or wishing it had never been.

It's true that 2016 was hard on some who are dear to me. The death of a mother. The unexpected and tragic death of a young brother. A brother paralyzed in an accident. Cancer. More cancer. Troubles with marriages. Troubles with children. Natural disasters. Wars. Trauma floods our world, and 2016 was no exception.

But that's it: 2016 was not exceptionally traumatic, as years go. For anyone who thinks so, other than on a direct, personal level, I recommend travel outside the tourist zones of a third-world country, or a good course in world history. Even my friends who were hit hardest during the year are finding reasons to be grateful and press on with life. The paralyzed man was planning how to carry on with his life goals even before the ambulance arrived, and discovered family and community support of amazing breadth and depth. Even as the man dealing with cancer struggles to adjust to his new reality, he—having spent time himself in third-world countries—takes care to express his gratitude for the medical care available to him. Across the world, our Gambian friends—who daily face tragedies that don't even cross the radar of most Americans—are revelling in the hope of their first democratically-elected government, ever.

It is not wrong to grieve. Grief is a proper response to tragedy. What troubles me is not personal grief, but the debilitating angst that appears to have gripped so much of our nation. I'm sure it has many causes, but my own theory is this:

We are trying to take on more tragedy than any one person was meant to bear.

Our ancestors experienced far more suffering and tragedy than most of us ever will, but it was localized, among their own families and neighbors. Their vicarious suffering was limited by the size of their small communities, and what's more, these were people they could personally help, hug, grieve with, and carry a casserole to.

Today we are awash in earthquakes, wars, murder, mayhem, homelessness, starvation, child abuse, torture, injustice, and other tragedies of any and every sort from every corner of the world. And that's just the news. Our movies and television shows assault our senses with violence and grief of even more intensity—and our limbic systems are lousy at separating fiction from reality.

What do we do in response? Maybe we change our Facebook profile pictures for a whle. Or toss some money in the direction of the problem. There is very little we can actually do to help in 99.99% of the tragic situations we are made aware of. This rots our souls from the inside out.

It is rotting our national soul.

We get angry, we become afraid, we act irrationally. We cast blame broadside and search wildly for scapegoats. We moan, we whine, we rant, we riot. We turn the pain inward and instead of facing challenges with courage, generosity, and gratitude, we let evil have the last word, denying all the wonder and good in the world. We convince ourselves that feeling miserable because of another's pain makes us righteous.

This kind of angst well deserves the scorn with which C. S. Lewis treated it in The Screwtape Letters.

The characteristic of Pains and Pleasures is that they are unmistakably real, and therefore, as far as they go, give the man who feels them a touchstone of reality. Thus if you had been trying to damn your man by the Romantic method ... submerged in self-pity for imaginary distresses — you would try to protect him at all costs from any real pain; because, of course, five minutes’ genuine toothache would reveal the romantic sorrows for the nonsense they were.

I don't recommend dental pain, much less something more tragic, as a curative for our national depression, but perhaps we do need a touchstone of reality. No matter how you feel about 2016, my recommendation for 2017 is less second-hand social media (things only shared or "liked" by our friends without further comment). Fewer movies, books, and TV shows that show us the worst of life in lurid detail. More that show us ordinary heroes responding with righteousness, determination, and courage. Not withdrawing into ignorance of what's happening in the world, but getting our news in the least spectacular fashion—more words, fewer pictures—and from a balance of sources. Staying away from news sites and blogs that only inflame our prejudices. Above all, immersing ourselves in the Good, the True, and the Beautiful. C. S. Lewis again: "It’s all in Plato. What DO they teach them in these schools?" (The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe)

Take a deep breath, refocus, and gain some perspective. Plant a garden. Snuggle a baby. Change a diaper. Volunteer at a soup kitchen. Wipe away a child's tear. Go for a walk in the woods and try to hear what the trees are telling you. Get up to see the sunrise. Travel to a foreign country and get out of the tourist zone. Bite the bullet and spend some quality time getting to know—really know—people who voted for someone other than your chosen presidential candidate. Smile at a stranger, unless you're in Switzerland, where that makes people nervous. Do something that will personally and directly make another person's life better. Bake bread. Write a letter. Focus on seeing and speaking the positive—or in the words of the Bible,

Whatever things are true, whatever things are noble, whatever things are just, whatever things are pure, whatever things are lovely, whatever things are of good report, if there is any virtue and if there is anything praiseworthy—meditate on these things.

Think on good things, and even more, do good things. George MacDonald was very big on the uselessness of thoughts and words that do not lead to action, but he did have a broad definition of what makes a good action. From The Princess and Curdie:

How little you must have thought! Why, you don't seem even to know the good of the things you are constantly doing. Now don't mistake me. I don't mean you are good for doing them. It is a good thing to eat your breakfast, but you don't fancy it's very good of you to do it. The thing is good, not you. ... There are a great many more good things than bad things to do.

Do you think it wrong to focus on the good when there is so much evil in the world? On the contrary, I'm convinced that to do otherwise is to surrender to the evil forces, and leads to an unhealthy mental state that does good for no one.

Let's say farewell to 2016 with gratitude for all the blessings and wonders that it has brought, and face 2017 with a cheerful courage.

Have a Happy New Year!

Permalink | Read 2024 times | Comments (2)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I was challenged by a friend's assertion: I am so glad I am not raising kids in these times. Neither of us is of an age where this is anything but a philosophical issue, but nonetheless I'm going to take it on.

Because I think this is a GREAT time to rear children. (No matter how many people insist the language is changing, I can never get my father's voice out of my head: You raise chickens, but rear children.)

Why do I think this is a great time to be a parent?

When I started to write this post, I realized I'd basically done it already, in my 30-part Good New Days Thanksgiving series from 2010. Six years later it's just as relevant. I wasn't focussing on childrearing by any means, but nearly all of my posts speak to reasons why I think it's great to be a parent today rather than in days past. Below I've included a list and links for all except the few for which I couldn't make that connection.

- Smoke-Free Living

- Openness in Politics

- Better Baby Formula

- Handicapped Access

- Ethnic Restaurants

- Pants as Suitable Clothing for Girls and Women

- The End of Forced Bed Rest for Mildly Ill Children

- Worldwide Communication and Travel

- The All-Volunteer Military

- Cleaner Air and Water

- Fathers and Children

- Digital Cameras

- Sexual Harassment Rules

- Reproductive Freedom

- Community Recycling

- Calculators and New Telephone Technology (These are a little outdated—a lot has changed in six years—but the principles are the same. Electronic devices have brought challenges to childrearing, but also fantastic opportunities.)

- Educational Choices (This is the most important of all in my book. Huge. But I'm listing these in original publication order.)

- Clothes Dryers (If you think this is trivial, I have four words for you: Cloth diapers. Rainy days.)

- Modern Dentistry

- Video Technology

- Food from All Over the World

- Ethnic Diversity

- Advances in Medical Care

- 911

- The Interstate Highway System

- Computers and the Internet

- And though I didn't mention it six years ago, the violent crime rate is much lower than it was when our children were little. Oddly enough, fear and angst are up, which is another issue, but crime itself is down.

Sure, there are things that are more challenging now. I'd be a lot more concerned if I lived in Germany or Sweden, for example, where there is so little educational freedom. But here? The educational resources and opportunities are so much greater than when our children were young, and almost infinitely greater than when my parents were rearing children. For that alone I'd love to have young children now, because that was definitely the most fun part of childrearing for me!

Permalink | Read 2861 times | Comments (2)

Category The Good New Days: [first] [previous]

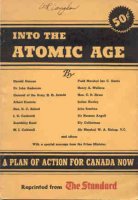

Into the Atomic Age: A Plan of Action for Canada Now edited by Sholto Watt (Montreal Standard Publishing Company, 1946)

Into the Atomic Age: A Plan of Action for Canada Now edited by Sholto Watt (Montreal Standard Publishing Company, 1946)

This, the fourth of my father's collection of early post-Hiroshima books (see here, here, and here), is as fascinating as the others, although the fascination has less to do with atomic energy and atomic bombs than with the immediate post-war culture.

The Greatest Generation was, in a word, terrified. For the scientists who developed the Bomb itself, the politicians attempting to address the consequences of its very existence, and those whose business was social and political commentary, these were "what hath Man wrought?" times, just over a century after Samuel F. B. Morse's famous telegraph transmission.

In 1946, The Standard, a Canadian national weekly newspaper, published a series of essays on the subject of atomic energy. The contributors were diverse, from military men to scientists to politicians to prominent men from a variety of fields, whether or not they bore any relation to atomic energy. (Contract bridge, anyone? Ely Culbertson was one of them.)

In the early years of my adulthood, I remember hearing people express great fear that we were headed towards a "one world government." They were suspicious of the United Nations, and viewed every international agreement through the lens of how it might affect our national sovereignty. I confess I gave them little respect, because I saw not a shred of evidence that anyone was interested in forming a unified world government.

But I was young. Even if I did grow up with "duck and cover" drills in elementary school, and spent time pondering the feasibility of building a fallout shelter in our backyard, I was blissfully ignorant of the politics of it all. Almost to a man, the writers of these essays were convinced that the only alternative to nuclear annihiliation was for all nations to give up their sovereign rights to an international government—either entirely, or "only" in the right to maintain armed forces and to wage war. The United Nations was brand-new in those days, and much hope was expressed that it would become the entity that would rule the world.

Fear makes people do crazy things, and put up with crazy things done by their leaders. It wouldn't surprise me if more freedoms have been lost through fear than through outright conquest. Fortunately for us, the one-world-government crazy idea never made it off the ground, though we've certainly lost plenty of freedom through fear—the Patriot Act and the bailout of companies "too big to fail," for example.

Be that as it may, here's a sampling of what people were thinking 70 years ago in response to what they perceived as the world's biggest threat. Text in bold is my own emphasis.

The picture of the next war thus becomes one of surprise, of sudden and unannounced aggression, of an “anonymous war,” in which the aggressor leaves no traces, mobilizes no armies, proclaims no hostilities.” A city might explode one night, another the next. In one night, a flight of rockets might demolish 20 cities and kill 40 million.

“This is the one-minute war of the future,” the scientists state. “This is the war that will be hanging over the heads of the nations of the world when all have possessed themselves of atomic explosive and sit in fear and trembling, wondering when their neighbor—or a country on the opposite side of the globe—may press the fateful key. … This picture is not projected a century or even half a century into the future; it is a possibility five years from now, a certainty in 15.”

To every man and woman it may be said with certainty that to secure a world authority is now part of the business of personal survival.

The more deeply one ponders the problems with which our world is confronted in the light … of the implications of the development of atomic energy, the harder it is to see a solution in anything short of some surrender of national sovereignty.

We are afraid that the understanding and sympathy that binds us together may not be as strong as the conflicts of national interest and the dark hates that threaten to separate us. Atomic energy in itself does not endanger us. It is the possible use of atomic energy by persons and nations motivated by hate that causes our fear.

The establishment of this world government must not have to wait until the same conditions of freedom are to be found in all three of the great powers. While it is true that in the Soviet Union the minority rules, I do not consider that internal conditions there are of themselves a threat to world peace. (Albert Einstein)

That one is evidence, as if any more were needed, that intellectual brilliance and practical sense do not necessarily reside together.

The scientists give us five short years in which to save ourselves and the world…. Five years in which we must build out of the present infant United Nations organization a world government capable of outlawing wars and the causes of wars. Five years in a world in which, from the dawn of Christianity from which our own democracy stemmed, it took nearly 2,000 years for our democracy to develop. Five years in which to project ourselves 1,000 years in maturity, in understanding, in social development.

But not to worry. The public schools can fix the problem.

I am optimistic enough to think that, with success in the intermediate and short-term period, we have a margin of twenty years in which to work. The long-term programme, the twenty-year programme, is the establishment of world government under principles of law, justice and human freedom. Such a world government cannot be imposed by force. It cannot be successfully negotiated by the statesmen of the nations of the earth. The plain fact is that world government requires as its foundation a moral and psychological sense of world community, and that foundation does not exist. To impose or to negotiate world government under existing conditions of prejudice and hate would do nothing more than set the stage for world civil war. The minds and hearts of men are not yet prepared for a world of law, justice and mercy.

We in North America are not prepared. Too many men despise women. Too many women despise their servants. Too many white men despise black men. Too many Christians despise Jews. This lack of sympathy and respect extends not only across group lines, but also within the groups themselves.

I feel that with twenty years to spare, the moral and psychological foundation for world peace can be laid. The hope is not that hundreds of years of history, tradition and custom will automatically and suddenly change their direction. The hope lies in the fact that it takes only a period of about a dozen years to implant a basic culture in the minds of a man—the period of childhood between the age of two and the age of 14.

The following may sound absurd now, but I know for a fact that Kodak built a special bomb-proof facility in Rochester, New York so that they could continue to manufacture paper in the event of nuclear war.

Drastic changes in defence measures would be called for, including the abandonment of all large cities, the decentralization of communications and the placing of all important factories far underground.

Not everyone was all gloom-and-doom. Some were downright science fiction in their ambitions.

The world-shaking discovery of atomic power, the greatest since the discovery of fire, can have only one of two end-results: either the unparalleled shattering of our civilization through atomic blasts, or an unparalleled era of peaceful science and mass happiness.

We have now within our grasp the means for creating an abundant life for all peoples of the world. Even before the development of atomic energy this was true, but now that we have tapped this tremendous new source of power, perhaps within half a century all nations can be raised to the same economic level occupied by the most advanced nations today.

There has never before been a discovery equal to that of atomic energy. The greatest discoveries of the past have advanced the material aids to humanity but a few years, but the forward move in the development of atomic energy must be measured in centuries. It can open the door to an age of plenty without revolution or war. It can make equality of opportunity a reality in our day. It can give the backward areas a chance to reach equality with others.

Some were downright nuts.

Why go slowly shepherding great liners through the locks on either side of the Culebra Cut when you could readily use atomic energy to blast a sea-level canal from ocean to ocean? (You would, of course, have to arrange for the temporary evacuation of all the population of the canal zone, but that, in these days of mass transfers of population, is perhaps not impossible.)

How many people realize that we could alter the entire climate of the North Temperate zones by exploding a few dozen or at most a few hundred atomic bombs at an appropriate height above the polar regions?

As a result of the immense heat produced, the floating polar ice-sheet would be melted; and it would not be re-formed. It is a relic from the last Ice Age, and survives today because most of the heat of the sun is reflected from its surface.

If it were once melted, most of the sun’s heat during the polar summer would be absorbed by the water and raise the temperature of the Arctic Ocean. Ice would form again each winter, but it would not cover nearly so large an extent as now, and would be thick enough to be melted in the succeeding summer.

As a result, the climate of Scandinavia would become more like that of Southern England, and the climate of Southern England would become much like that of Portugal.

As usual with all grandiose projects, there are snags.

Thus with the northward movement of the warm temperate and cool temperate zones, the arid zone would move too; and the countries which had the prospect of being turned into the Sahara of the future might reasonably object!

Perhaps it would be best to begin in a small way, by melting a small chunk of the ice-sheet with the aim, say, of slightly ameliorating the climate of Nova Scotia and Labrador, and seeing what happened elsewhere, before attempting anything further.

And we think we have climate change problems now.

Some writers had a better grasp of political realities than others.

We should do well to take stock from time to time of our original purpose in establishing the UNO [United Nations]. What was that purpose? The commonest reply perhaps would be, “To preserve peace.” For many years statesmen have been in the habit of saying, “The greatest interest of our country is Peace.” They have said that usually with complete sincerity and in bad confusion of thought.

For it is not true.

Any nation which suffered invasion would fight if it could. That is to say, it would sacrifice peace for the purpose of defending its national independence. Which means that we do not put peace first; we put defence first: the right to existence, national survival. And no international organization can succeed if it ignores this truth that defence, security, the right to life, must in the purpose of men come before mere peace. We could have had peace by submission to Hitler and Hirohito; we refused it on those terms.

But that brings us to the question: “What is defence? What rights of nations must an international organization defend if its purpose is to be fulfilled? Russia declares that its rights of defence must include “friendly” governments in the whole of Eastern Europe. What precisely does “Friendly” mean? More than once Russia has described Switzerland as “unfriendly and semi-Fascist.” On one occasion Russia refused participation in an international conference on aviation because Switzerland was included. If each nation is to claim in the name of defence conformity with its own special views to the extent which Russia seems to claim that conformity, a workable international organization for collective security is going to be extremely difficult to establish.

Despite the book's small size, there's a lot more to Into the Atomic Age, from following a spelunker deep into a cave in search of a place to set up an underground factory, to the convincing argument that there is no effective way for international inspections to prevent a country that has nuclear energy from also being able to make nuclear bombs. I wish those who negotiated our treaty with Iran had read this book.

Why do people hate the rich?

Perhaps it's simple jealousy, especially since we tend to define as "rich" anyone who has more money than we do ourselves. Differences in wealth and power have been around forever and likely always will be. Jealousy and resentment have plagued us at least as long.

The hatred seems particularly virulent these days, however, especially among those who are themselves wealthy beyond the dreams of most of the world, both now and throughout history. It has bubbled up recently in the idea that being rich somehow disqualifies many of the people whom Donald Trump has chosen for his Cabinet.

I hate conspicuous consumption, and I despise waste even more. Most of all, I grieve that the lifestyles of the rich and famous, fueled by unwise use of money, consumes their souls like an aggressive cancer. But as Scottish author George MacDonald—himself often desperately poor—takes pains to make clear, the love of money destroys the souls of those who have too little just as surely as it destroys those who have too much.

But through the years I've come to respect most rich people and see their importance to all of us.

Rich people get things done.

We all know spoiled "rich kids" of any age who have inherited their wealth and done nothing to earn it, nothing to increase it, and nothing good with it. But by and large, people become wealthy because they make things happen. They work very hard, too—but hard work alone is insufficient. The same character traits that enable some people to get rich often also enable them to accomplish great things. Sure, there's some luck involved, but it takes something else to make that luck work in your favor—a something else most of us do not have. (One of my favorite quotes, which I learned thanks to my friend the Occasional CEO, is J. Paul Getty's secret to success: 1. Get up early. 2. Work hard. 3. Strike oil.)

The neighborhood we live in would probably be considered lower middle class. There are people of all classes in the huge—over 900 homes—subdivision, but on average I'd say lower middle class covers it. Our kids go to the same high school as kids from some very wealthy neighborhoods, and there's certainly some resentment over their cars and fancy clothes. But when it comes to doing things for the school, the wealthier parents—at least those wealthier than us—lead the pack. And when a planning decision at the school board level threatened to split up our school, it was people from the rich neighborhoods who saved ours along with their own, because they had the experience, the knowledge, and most of all were willing to put in the time and effort, to propose and fight for an acceptable alternative plan. The rest of us cared, but the wealthy made it happen, not because they were rich, but because they knew what to do and worked till the job was done. Frankly, I'd consider that an asset in any Cabinet position.

Our recent trip to New York City, with its museums, big and small, public and private, also showed me the advantage of having rich folks around. Where would high culture be without the wealthy? Not only do they support art, music, and theater by commissioning works, but they collect, preserve, and protect works of art—art that the rest of society may not fully appreciate for a century or so.

Not to mention the fact that rich people create jobs for the rest of us. Even those fancy cars, ridiculously large yachts, and over-the-top opulent houses provide work for a whole bunch of people. Most important of all is that the people who have the qualities that enable them to become rich are the ones who create the industries that we depend on. Would I rather see a rise in family-owned industries, small farms, and sole proprietorships, in which more people work for themselves rather than for someone else? Sure. But not everyone can do that, and not everyone wants to. Someone like me can give a poor person a handout, but a rich person can provide a job that will give him self-respect and lift him out of poverty.

We don't have to approve of everything about the way rich people behave to recognize their value to society—and to a government. Would you be happier if John, Robert, or even Ted Kennedy were in one of the Cabinet posts? Take a closer look at some of that family's behavior, and especially how they amassed their fortune.

Are many wealthy people being irresponsible with their money? Certainly. Aren't we all? It's a disease as widely distributed as the common cold, afflicting businesses, institutions, and governments even more than individuals. But that issue is completely irrelevant to someone's fitness for a Cabinet post.

Envy is an ugly trait, and a terrible advisor.

Reading my way through the massive World Encyclopedia of Christmas (thanks, Stephan and Janet!), I've come to be more understanding of those, like my Puritan ancestors, who banned the celebration of the holiday. It had become anything but a holy-day, filled with drunkenness, lewdness, and all sorts of riotous and unseemly behavior, hardly appropriate to the sublime occasion. In those days, the "war on Christmas" was led, with good reason, by Christians themselves. If our moral behavior is no better these days, at least the holiday is kinder to children.

It is unfortunately fashionable among Christians to mock other Christians who worry about what they think is a secular war on Christmas. Despite Martin Luther's approval of its use in certain circumstances, I think mockery is a very low form of argument, hardly suitable for one human being to use against another. Be that as it may, I don't think there's a war on Christmas.

Call it cultural appropriation.

Christmas is one of the greatest festivals of the Christian year—among many Christians the celebration lasts 12 days. Some would say Easter is more important, but as I wrote five years ago,

If it is unique and astonishing that a man so clearly dead should in three days be so clearly alive, and alive in such a new way that he has a physical body (that can be touched, and fed) and yet comes and goes through space in a manner more befitting science fiction—is it any less unique and astonishing that God, the creator of all that is, seen and unseen, should become a human being, not in the shape-shifting ways of the Greek gods, but through physical birth, with human limitations?

Christmas is the celebration of this Incarnation: The God who in the act of creation made the world separate from himself, at a specific time in history implanted himself in that world, not from the outside like some alien visitation, but from the inside, as deep and physically inside as a human baby in a woman's womb. This is what we celebrate at Christmas.

Just as there is commonly a lot more involved in the celebration a wedding than the legal act of marriage, many traditions have enriched the essential celebration of Christmas. From gift-giving to special foods, from carols to children's pageants, from decorated Christmas trees to stockings hanging by the chimney, beautiful customs have grown like many-faceted crystals around the core meaning of Christmas.

Indeed, these traditions are so special that millions hang onto them who reject the idea of God entering the world as a particular baby in a specific place and time. They even retain the name "Christmas" for this eviscerated holiday. Once upon a time that bothered me, but then I recognized that the symbols and traditions of Christmas are so rich and so powerful that—like a Christmas tree—they can retain life and beauty and a pleasing aroma for quite a while even when cut off from their roots.

Using the term "Christmas" for a celebration that no longer acknowledges nor respects the holiday's origin and history may be what is derisively called cultural appropriation, but I'm no longer convinced that's a bad thing. Christmas carols are very popular in Japan, a country where less than 2% of the people believe the words they are singing. In Europe, Christian holidays are celebrated by people who probably know no more about the meaning of the days than that the stores are closed and they don't have to go to work. In America, children eagerly count the days till Christmas, who neither know who Christ is nor have ever been to mass.

More power to them. Cultural appropriation at its best is a terrific learning opportunity. For ourselves, let's take pains to celebrate the whole tree, root and branch. Beyond that, I see no need to fret about keeping Christ in Christmas. He's there, in every lovely symbol and custom, waiting patiently, as he always does, to be revealed at the right time.

Merry Christmas, everyone!

Permalink | Read 2002 times | Comments (2)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Our daughter and son-in-law have always made a point of helping their six children acquire basic life skills at an early age. I've mentioned previously that by age four the kids are fully competent to chop vegetables for a salad, having begun by cutting up mushrooms at age two.

On a recent visit, we were blown away by their skills on a different front.

The family has a small apartment above the garage that is used by overnight guests. This time it was our eight-year-old granddaughter who took complete responsibility for preparing the apartment for our visit, from cleaning the bathroom to putting fresh sheets on the bed. She did an excellent job.

And on each of our pillows she put a neatly-folded set of towels ... and two pieces of chocolate.

George Friedman has written a clear explanation of why we have the Electoral College. It's worth reading if you're one of those who want to dismantle it—or one of those unsure if it's defensible.

I understand, and agree, that a direct democracy is not necessarily the best political system. Pure democracy, after all, is another word for the tyranny of the majority—or worse, if the choice is not binary. I also agree with the assertion that at least some form of free market is necessary to make a democracy fair, because without economic freedom all other freedoms go out the window. What puzzles me is Switzerland.

In the European Union, equality and unanimity between members is critical, but the United States chose a much more sophisticated system, combining a deep democratic process, with mediating layers to limit or block public passions.

The United States is a vast nation with highly differentiated interests. From the beginning, the founders were forced to face the fact that holding the nation together required concern for the interests of all states, and not only for those densely settled. A pure democracy would consider the nation’s interests as a whole. The founders were aware that the nation was not a whole, although all regions were needed.

The United States is a geopolitical invention. The 13 original colonies were very different from each other. As the nation expanded westward, even more exotic states became part of the union. Constantly alienating smaller states through indifference could undermine the national interest. The Senate and the electoral college both stop that from happening, or at least limit it. Any state can matter in any election.

You might charge that this is undemocratic. It is. It was intended to be. The founders did not create a direct democracy for a good reason. It would have prevented the United States from emerging as a stable union. They created a republican form of government based on representation and a federal system based on sovereign states. Because of that, a candidate who ignores or insults the “flyover” states is likely to be writing memoirs instead of governing.

I get it. It makes a lot of sense. But Switzerland, though much, much smaller (about half the size of South Carolina), comprises 26 cantons that are at least as diverse as the American states. Think four official national languages and cultures, and that doesn't even count the dozens of different forms of German. Moreover, its individual cantons have much more independence than the states of the U.S.

Yet Switzerland is both a direct democracy and a very stable union. Is it the size that makes the difference? Or something else?

Here's another George Friedman article that asserts, Great leaders did not make history. History made them. He's not talking about revisionist history, but about the impotence of leaders to kick against the goads. It speaks to my contention that a Trump presidency will be neither as bad as his opponents fear, nor as good as his supporters hope. Even with as powerful an Executive as we have in the United States, other factors are much more important than who's in the White House. As Shakespeare put it, There’s a divinity that shapes our ends, rough-hew them how we will.

In thinking about the presidency – or political leaders anywhere – it is important to distinguish between ambitions and constraints. ... Beyond constitutional limits on a president, reality imposes others. Lincoln did not want a civil war; Roosevelt wanted to end the depression; Reagan wanted to energize the economy; and when he took office, Bush had no intention of invading Afghanistan nine months later. But it really didn’t matter what they wanted. Other forces were at work shaping and undermining their presidencies. Given their circumstances, some could achieve some of their goals, none could achieve all of them, and few could achieve them in the manner they planned.

Leaders aren’t iconic, they are human beings. The idea that they will rebuild society in a manner that is more just to one group vastly overstates their power. Obama is a case in point. He was expected to end all wars, end the rage against the United States in the Islamic world that led to terrorism, create jobs and so on. He likely believed in many of these things, and he may well have expected to accomplish them as president. ... Leaders inevitably disappoint, because they must claim extraordinary powers.... Their election is followed by great excitement and long periods of growing disappointment.

Roosevelt and Reagan were both regarded by opponents as completely unsuited for office. Reagan was called an ignorant and evil actor, and Roosevelt was a rich dilettante with an empty head. Abraham Lincoln was likened to a monkey and regarded as an ignorant and uncouth lout who would shame the country. And these weren’t Southerners talking. ... None were devils and none were miracle workers.

The whole article is short, and worth reading, whether you're happy, depressed, or merely confused by the current political situation.

I still believe that the American executive branch is too powerful, but Friedman's point is well made. I like his take on President Reagan and the fall of the Soviet Union (emphasis mine):

We like to speak of Reagan defeating the Soviet Union. The truth is that the Soviet Union was collapsing regardless of any outside effort. Reagan did not impede the process and certainly contributed to it. What he intended happened, but it was minimally influenced by anything he did. The Soviet Union fell because of internal failures built into the system.

May we always be found impeding the evil and contributing to the good, with neither elation nor panic over who holds the highest political office.

I don't even know who George Friedman is, but I've read a number of his essays recently, and I'm hooked. From November 7, The European Diaspora touched a nerve for me that has been aching since elementary school. You see, my ancestors were all early immigrants to this country, and in my school that was not respected. If your ancestors came to America recently enough that your parents or grandparents were immigrants, that was cool. If they came here really long ago, i.e. if you were of American Indian descent, that was the coolest of all. But in between? You were white-bread, plain vanilla, WASP-ish. Definitely uncool. I used to joke that I was considering becoming a Catholic, as that was the only part of White Anglo-Saxon Protestant I had the power to change.

For reasons I still don't know, my parents never shared much about my family heritage and resented the homework assignments that asked about it. The message I heard was simply that we were all Americans, and that was what was important. Did my mother grow up hearing her grandmother talk about being a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and had she found that boastful, or boring? Were they aware of some anti-immigrant sentiment and did they want to keep it far away from me? I have no idea. But of course I interpreted the silence as meaning there was something negative or shameful about my ancestry. And being ashamed, I was foolish and never talked with them about the atmosphere at school.

It's really not any better now. We live in a time when "dead white [European] males" are safely vilified, and living ones not much better off. "Black Pride" is a positive, uplifting thing; "White Pride" evokes images of the Ku Klux Klan, Adolf Hitler, Skinheads, and Deliverance.

I can't imagine why the color of one's skin should be a matter of pride for anyone, but long ago I grew tired of being ashamed of my heritage. Studying genealogy gave me a better sense of history than school ever did, and assured me that my family tree is as filled with heroes and rogues, the persecuted and the persecutors, those who were well-off and those who were desperately poor, as anyone's—even if it did reveal a still more solid base of white, British Isles/northern-European, early immigrants.

George Friedman is kinder than most to my family heritage. We, too, come from courageous survivors, refugees who were desperate enough to leave everything in search of hope. Where we have travelled, we have done terrible evil and brought immense good. But mostly we have simply been human families. If our stories are a little older than those of some immigrants, and newer than others, they aren't any less important.

When I come to this part of the world [Australia/New Zealand], I am always struck by a concept we never hear about: the European diaspora. The various peoples of Europe have collectively constituted a vast and ongoing diaspora. We speak of the Jewish, Armenian or Chinese diaspora. But somehow we never think of Europe as scattering its deeply divided peoples throughout the world.

There is a difference between imperial conquest and diaspora. Imperial conquest is carried out by governments and the elites. They do it for power, money and strategic advantage. The rest of us, who have moved from one country to another, are part of a diaspora. We hope to find a better life, some food to eat, a house to live in, a policeman who will not beat us. Thus, the great European conquest of the world had two sides. One was the movement of the geopolitical plates of the world. The other was the individual acts of desperation.

The diaspora was not peaceful. Europe’s wars shaped the places Europeans sought refuge. And the diaspora displaced, subordinated and killed those who were there before, much as the Zulus, the Comanche and the Aztecs did when they arrived. The settlement of the diaspora involved brutality, as do many consequential human acts.

It is odd ... that many think the settlement of the [European] diaspora is unjust because, in the process, others were displaced. But it is simply human, and like all human things, it is both just and unjust.

The European diaspora included migrants from all of Europe’s countries. There are vast areas where Spanish and Portuguese are spoken, and other regions where people converse in French or Dutch. But I will assert that the English-speaking regions have had the largest effect on the world. This may not be a popular view, but it is true that the colonies created by the English became the places where refuge can be found now and in past centuries. Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States, received the English language, marvelous in its subtlety and dynamism. And these countries have formed a web of relations with each other that has been a driver of the global system. They are not always comfortable with each other, but they have fought together and created together. They have also welcomed the wretched refuse of Europe’s teeming shores with an ease and openness not quite matched by others.

Would I still be thrilled if genealogical research confirmed the one, long-ago possibility of a Native American ancestor? If a DNA test reveals something sub-Saharan African or Ashkenazi Jew? Absolutely. But I'm done with being embarrassed by my heritage, even if it turns out to be 100% northern European. My parents were right: we are all Americans, and that's what counts. I'd go further: we are all human beings, made in the image of God, fallen and broken, but capable of being redeemed—and that's what counts. But particulars count, too: my family, my community, my culture, my heritage—and yours, and yours, and his, and theirs. No heritage has a monopoly on shame, or pride.

More surprising than Brexit, more shocking than the election of Donald Trump, is the news from the Gambia: President Yahya Jammeh has not only been voted out, but has conceded the election and appears ready for a peaceful transition of power. The unexpected winner is Adama Barrow, whose name makes me smile because I know that he probably has a twin sister. I've not seen that confirmed, but I know from our visit to the Gambia this year that male/female twins are not uncommon there, and are usually named Adama and Hawa (Adam and Eve).

You can find quite a bit about the election on the Internet, but here's a bit from an Economist article:

Mr. Barrow staged a big political upset in results announced on December 2nd, winning by 45.5% to Mr. Jammeh’s 36.7%. Even more surprisingly—and to his great credit—Mr Jammeh quickly conceded defeat. By the evening, streets that many had feared could be a battleground were full of partying crowds tearing down posters of their outgoing president.

The election was scary for a while, I'm told, because the borders were sealed and communication with the outside world cut off. But afterwards, my friend who lives there, and who was also living in Germany in 1989, described the scene like this:

Everyone is now running around celebrating. It feels a lot like when the Berlin Wall came down, but without the beer.

Everyone is full of hope, but it's a big transition and the Gambia needs all the prayers it can get. Some fear another coup (that's how Mr. Jammeh came to power in the first place), and the country is desperately poor and lacking in natural resources. Mr. Barrow has a difficult road ahead of him. But hope is a great thing.

Gambians vote using a system of marbles and metal drums. There's a video in this BBC report that shows how it works. What I like best is that it was filmed in Brikama, where we spent most of our time, and everything looks and sounds so pleasantly familiar.

What adjectives come to your mind when you think of someone who voted for Donald Trump?

Racist, homophobic, sexist, xenophobic, selfish, idiotic? Probably.

How about compassionate, loving, open-minded, generous? I didn't think so.

Ever since the election I have found myself in the incongruous position of defending the supporters of Donald Trump. Perhaps it's due to my shock at the virulent attacks against them from the mouths and pens of people who have in the past taken pride in their openness, tolerance, and love of diversity. Maybe it's because of my natural tendency to be contrary. My daughter said, "Mom, if you were a salmon, you'd be swimming downstream." I had to think about that a bit.

I'm pretty sure, however, that my change of heart came mostly because I took a good look at the only Trump supporters in my circle of friends. We have friends who are staunch supporters of Bernie Sanders and reluctantly switched to Hillary Clinton when she became the party's nominee; friends who supported Hillary Clinton all along; friends who couldn't stand Donald Trump from the beginning and voted for him only because the alternative was unthinkable; and friends who voted third party or sat this election out because they couldn't bear to cast a vote for either Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton. Out of all my friends, only two openly cheered for Trump.

So I took a good look at them.

- Smart, educated, and well-travelled

- Raised five children, as a multi-racial, multi-ethnic family

- Personally settled and supported over a dozen refugees, and assisted hundreds more

- Took in hundreds of the most difficult-to-place foster children

- War veteran

- Cleaned the homes—often on hands and knees—of elderly people in the community who could no longer do the work themselves

- Support orphans and others in need—financially and in person—on three continents

- Open their home and hearts to countless visitors from all over the world, of diverse cultures and religions

- Are unabashedly and enthusiastically Christian, for whom that is always a reason to be more active, inclusive, and loving—not less

- Have uncompromising moral values which never deter them from loving and helping those who do not share their standards

- Have a joyous enthusiasm for life, in good times and in bad, that spills over into everyone they meet

- Are called Mom and Dad by enough people around the world to populate a small city

These are the only Trump supporters I know well enough to judge, and I don't have a fraction of the cred I'd need to cast a stone their way.

Before we write off as immoral subhumans half the people we share this country with, maybe we should get to know them better.