It's been a month since I linked to a Viva Frei "Sidebar" video, more because there's been too much to choose from than than too little! This one is a two-hour long interview with Blake Masters. As with most of their Sidebar guests, I'd never heard of him, but if he wins in his attempt to become a U. S. senator from Arizona, I may learn more about him. Or if one of our grandchildren wins a Thiel Fellowship....

Blake Masters is president of the Thiel Foundation and the Fellowhip is their flagship program. He talks about it briefly during the interview, from about 32:32 to 41:56. The following video should start close to that point; you'll have to stop it yourself as a quick search did not show me an easy way to accomplish that automatically. The rest of the interview is also interesting, but who has two hours to listen to it?

Basically, the foundation believes that too many people are going to college, and funds efforts to do something productive without it. As Masters puts it, "We pay young people to drop out of college." About 10% of the fellowship recipients eventually go back to school, mostly for engineering degrees or other practical majors. MIT has even been known to hold students' places open for them.

Masters has some other good suggestions for taming the massive quagmire that higher education has become. One of them has long been a favorite of my husband's: find a way to make colleges have "skin in the game" of student loans. Right now they have every incentive to push students toward massive, unmanageable debt, and no incentive not to. (Professor friends, please don't stop the video in disgust when Viva suggests that college professors are the ones benefitting from the out-of-control costs—Masters immediately corrects him on that point.)

Masters has several other interesting things to say—the interview covers a lot—but nothing as easy to pull out separately as the above. If you have two hours you can spare to listen—there's no need to watch—go for it. Warning: the language is sometimes not what I would consider acceptable, though if I remember right the section about college is okay.

The impact of the Middle Ages on our human psyche cannot be overestimated. It's no coincidence that our most beloved epic dramas, from The Lord of the Rings to Star Wars, from The Chronicles of Narnia to The Green Ember, feature knights and swords, chivalry and heroism, glory, honor, and worship.

Facebook thought I would enjoy this paean to medieval times, and for once they were right. (5.5 minutes)

Permalink | Read 1098 times | Comments (2)

Category Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

What was happening at the beginning of the 1960's?

I've long been a fan of Randall Garrett's Lord Darcy books, so when I found the Kindle version of Randall Garrett: The Ultimate Collection for 99 cents, I leapt at the chance to read some of his other stories. Nothing so far has come close to the Lord Darcy books in quality, but they've mostly been fun to read.

Recently I read The Highest Treason. It's short, under 23,000 words, and was originally published in the January 1961 issue of the magazine Analog Science Fact and Fiction. You can find a public domain version at Project Gutenberg.

The Highest Treason deals with a subject familiar to me, one I first encountered in Kurt Vonnegut's Harrison Bergeron, first published in October 1961, in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. That one is much shorter, only 2200 words, and can be found here in pdf form.

C. S. Lewis's Screwtape Proposes a Toast was next—and my favorite. You can read it here, in the December 19, 1959 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. I don't have a word count, but it is also quite short.

December 1959, January 1961, October 1961. Three stories written as the 1950's passed into the 1960's.

All three have as their premise the consequences of a culture of mediocrity, in which excellence in anything—beauty, art, sport, thinking, work, character—is abolished for the sake of making everyone "equal." There must have been something going on at that time period to make it a concern for at least three such varied authors.

What would they think today? From the demise of ability grouping in elementary schools, to "participation trophies," to branding as racist and unacceptable the idea that employment and leadership positions should be awarded on the basis of merit and accomplishment, we have come a long way down this path since 1960.

Here's hoping it doesn't take near-annihilation by space aliens—or the flames of hell—to wake us up.

Permalink | Read 1141 times | Comments (1)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

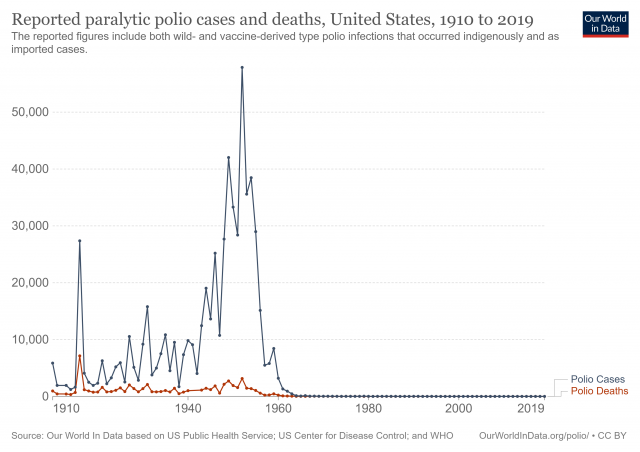

In research inspired by my previous post, Measles Wipes Out the Immune System?, I discovered this interesting article on another disease, polio. Most of all I was struck by this explanation of the huge spike in the disease that occurred in the middle of the 20th century:

Up to the 19th century, populations experienced only relatively small [polio] outbreaks. This changed around the beginning of the 20th century. Major epidemics occurred in Norway and Sweden around 1905 and later also in the United States. Why did we see such large outbreaks of polio only in the 20th century?

The answer ... lies with hygiene standards. As polio is transmitted via the fecal-oral route, the lack of flush toilets and the lack of safe drinking water meant that children in the past were usually exposed to the poliovirus before their first birthday already. At such a young age, children still benefit from a passive immunity that is passed on from their mothers in the form of antibodies. ... Thereby, virtually all children would contract the poliovirus at a very young age. While protected from developing the disease thanks to the maternal antibodies, their bodies would produce their own memory cells in response to the virus and that ensured long-term immunity against polio. The latter is important as the mother’s cells have a half-life of only 30 days (starting from the last day of breastfeeding). Once the maternal antibodies decrease in number, children lose their passive immunity. As hygiene standards improved, the age at which children were first exposed to the poliovirus increased and this meant that the maternal antibodies were no longer present to protect children from polio.

That improved sanitation was a driving factor in polio outbreaks is also illustrated by the fact that the age at which polio was contracted increased over time. During five US epidemics in the time period 1907-1912, most reported cases occurred in one- to five-year-olds, whereas during the 1950s the average age of contraction was 6 years with "a substantial proportion of cases occurring among teenagers and young adults." Being exposed to the poliovirus after losing the protection from maternal antibodies meant that they were more likely to get polio.

The dramatic dropoff in cases in the 1950's shows the effectiveness of the newly-developed polio vaccine.

I find the progression fascinating. The world achieves a steady-state coexistence with the disease, in which mothers' acquired immunity protects their children while the children develop immunity of their own. Then, thanks in large part to laudable and desirable public health advances, the disease gets the upper hand and skyrockets. (The article does not mention this, but I'm certain that the decline of breastfeeding during this time period also contributed significantly to the disruption of the natural protection against polio.) Finally, vaccine development and widespread implementation nearly wipes out the disease.

The emphasis on "nearly" is important. There is hope that, like smallpox, polio will completely eradicated. Smallpox dropped off the list of recommended vaccines when the risk from the vaccine became greater than the risk of the disease. Someday soon I hope the polio vaccine will also be relegated to history. In the meantime, however, we must not become careless nor complacent about the vaccine. We no longer have the natural immunity passed between mothers and children, and nothing short of a catastrophe will return us to those times. We have reason to feel quite safe here in the United States, but consider this from the article:

As of 2017 the virus remains in circulation in only three countries in the world—Afghanistan, Pakistan and Nigeria.

Do we want to completely shut our doors to the visitors, immigrants, and refugees who come here from these countries? If not, we'd better continue to make vaccination against polio a priority.

Here's a very strange news story out of the usually-reasonably-trustworthy BBC News: Measles resets the immune system.

"Immune amnesia" [is] a mysterious phenomenon that's been with us for millennia, though it was only discovered in 2012. Essentially, when you're infected with measles, your immune system abruptly forgets every pathogen it's ever encountered before—every cold, every bout of flu, every exposure to bacteria or viruses in the environment, every vaccination. The loss is near-total and permanent. Once the measles infection is over, current evidence suggests that your body has to re-learn what's good and what's bad almost from scratch.

Scientists have known for decades that even after they recover, children who have been infected with measles are significantly more likely to fall ill and die from other causes. In fact, a study from 1995 found that vaccinating against the virus reduces the overall likelihood of death by between 30% and 86% in the years afterwards.

I find this bizarre and completely counter-intuitive. Nearly everyone my age and older has experienced a measles infection, and this phenomenon doesn't make sense given my experience and that of those I know, i.e. that of normal, healthy, well-nourished children who have suffered from measles. I say "suffered," but will make the point that in my case it was hardly suffering. Measles was just one of several infections that got you out of school for a week or two and earned you extra parental attention and breakfast in bed.

What we were not is sickly. We were nothing if not robust. Polio had been licked by the new vaccine, and everything else we endured for a few days and then were back in the business of causing general havoc in the fresh air and sunshine.

Probably the greatest threat to our health was secondhand smoke: nearly everyone smoked nearly everywhere. That and the strontium-90 cloud that passed through our village in my early childhood....

If our immune responses had been wiped out by getting measles, I would think we'd have seen an increase in illnesses post- versus pre-measles. Does anyone of my generation remember that? I don't. If our immune systems forgot every other vaccine and pathogen they had previously encountered, they seem to have re-learned their responses quite quickly.

Certainly the subsequent generations of children do not seem to me to be noticeably healthier than my own, if you consider the "normal, healthy, well-nourished" cohort I mentioned above. New vaccines have kept them free of most of the early childhood diseases, but instead of dealing with a few days of illness they're at increased risk of lifelong asthma, any number of food allergies, and even autism. Correlation does not imply causation—but let's just say that I don't feel I got a bum deal growing up in the 1950's. Except for the secondhand smoke part.

I'd like to hear more about this new discovery of the effects of measles. Crazier things are true. It just seems weird to me.

Recently I re-read The Light in the Forest, a book from my childhood, though I hardly needed to read the whole book to find the passage I quote below. I could almost have quoted it from the memory of my first reading some sixty years ago.

These are the words of an old slave, in colonial America, explaining how easy it is for those born free to lose their liberty.

Every day they drop another fine strap around you. Little by little they buckle you up so you don't feel it too much at one time. Sooner or later they have you all hitched up, but you've got so used to it by that time you hardly know it.

I like to cook. Really, I do. This happened overnight.

Permalink | Read 989 times | Comments (2)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I read a lot.

Now, "a lot" is pretty much a meaningless term. Since I started keeping track in 2010, I have averaged 72.2 books per year (5.85 per month). For a scholar, that would not be much, but a pitifully small* number. However, compared with that mythical being, the average American, it's impressive, since for him it would be 12/year (mean) or 4/year (median). (I'm using the gender-neutral sense of "him," as I almost always do, but it is worth noting that women, as a group, read significantly more books than men: 14 vs. 9, 5 vs. 3 annually.)

Whatever. The point is that I like to read, and since 2010 I have kept a few statistics. The advantage of data is that it can surprise you. For example, 60% of my reading since that year has been fiction, although it feels as if that percentage is much lower. Partly that is because I like to read books recommended by or for our grandchildren, and often those books are shorter and quickly read. That's changing some now due to their growing taste for books like the one I just finished: Brandon Sanderson's 1000-page The Way of Kings.

Most likely the reason it feels as if I've read more non-fiction than I actually have is that I find it difficult to read a non-fiction book without writing a review of it, which can easily take longer than reading the book in the first place.

Take my current non-fiction book, for example: Loserthink, by Scott Adams. I have just finished reading Chapter 1, and already there are seven sticky notes festooning the pages, marking quotations I would want to include in a review. This is not a sustainable pace. Too many quotes and it becomes burdensome to copy them, even from an e-book. Moreover, I've learned that the more I include, the fewer people actually read, making it a waste of time for all of us. Often I include many of them anyway, for my own reference. But sometimes it reduces my review to little more than "read/don't read this book."

Still looking for the via media.

In the meantime, I'll get back to enjoying Loserthink. I don't like the negativity of the title, but Adams carefully explains its purpose. In short: it's not a label for people, but for unproductive ways of thinking, and short, negative labels make it easier to avoid bad things. I know from the interview with Scott Adams that I included in my Hallowe'en post that his personality can be abrasive, and I occasionally have doubts about listening to someone with well-developed skills in the art of persuasion. None of that means, however, that what he has to say won't be of much value.

There was no reason the day should have been unusual.

It began with a phone conversation with a good friend, and ended with choir practice. In between, I ran errands: to Jo-Ann's for a new sweatshirt, to the library for a couple of books, one by Brandon Sanderson and the other by Scott Adams. Finally, I ended up at the grocery store, for—well, for all those things you can get at a grocery store. Nothing unusual.

Errands don't generally put me in a good mood. Perhaps these should have, because they were 100% successful for a change, but that's not why I came home euphoric.

People were smiling. They were laughing. They were joking with one another. Just as we used to do before masks covered our faces and suspicion darkened our hearts.

This battle isn't over yet. But it was a good day.

Permalink | Read 1015 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

As I wrote before, we recently made our first airplane voyage since before the start of the pandemic. I was surprised at how rusty we were in what used to be accustomed procedure!

Overall, I was impressed, as I usually am, by Southwest Airlines. We flew during their recent—and never satisfactorily explained—outage, and our outbound flights were cancelled. However, we were automatically rebooked, within minutes of that notification, on a flight that left later the same day and arrived at our destination earlier, a much better situation for us. Between that and having automatic TSA Precheck, our airport experiences were problem-free. And I'm very happy about the improved cleaning and air filtration procedures, since in my experience an airplane is nearly as dangerous as an elementary school when it comes to challenges to the immune system. That part of the flight felt good.

Not that we had all that much chance to experience the new, fresher air, as masks were required to be worn at all times, even between bites and sips while eating and drinking. Fortunately, the between bites part was not aggressively enforced, but neither was there all that much opportunity for eating and drinking.

I can handle a mask, when necessary, for short shopping trips, and can make it through a choir rehearsal or a church service, albeit with difficulty. If I had to wear a mask for my job, I'd be applying for a medical exemption. I have no disability other than age, but that was good enough to get me priority for the vaccine, so maybe it would work. Fortunately, employment is not an issue.

Wearing a mask for the trip was hard. Ours was a relatively short flight, but that was three hours, and of course you have to add in the airport time on either end. Still, we managed all right, as far as I could tell.

The scary part was on the flight home, when I had the elbow room to use the sensor on my phone to check my blood oxygen. I know I'm good at sleeping on airplanes, but I couldn't stay awake to read a very interesting novel, and that concerned me. The sensor on my phone is hardly as accurate as a medical pulse oximeter, but there has to be something wrong about the fact that it consistently reads between 95% and 100% at home (usually on the high side of that), and my readings on the plane were between 84% and 90%! Pulling the mask away from my face for several breaths got it up to between 93% and 97%. But for how long had I been in the danger zone? Was the problem due to wearing the mask, or the altitude, or a combination? All I know is that when I got back home the numbers were up to 97%-100% again.

I'm trying not to think too much about the fact that our overseas family, including small children, had to endure two very long transatlantic flights for their Christmas visit here, and were forced to wear medical masks because their own cloth masks—similar to mine—were deemed to allow too much air exchange.

This won't stop me from flying again, even overseas when that is allowed. Family is too important. But at my age I need all the brain cells I can keep. Who doesn't, at any age? (That's one reason I avoid anesthesia whenever possible.) I'm more and more convinced that the harmful effects of our pandemic regulations are only just beginning to be felt.