For tomorrow's primary election, I voted by mail.

Rather against my better judgement, I admit, as I far prefer in-person voting and that only on the "real" election day. I did "early voting" once and it felt so false I never did it again.

I have voted absentee before, and felt okay with that. In fact, that's why I had a mail-in ballot for this election: given our schedule—or what used to be our schedule, pre-pandemic—I didn't want to find myself disenfranchised by being out of town. What I've done before when I have been at home on Election Day is to vote at my local polling place and have them nullify my mail-in ballot there.

I've voted in person once already during this COVIDtide, and felt at least as safe as I do grocery shopping. But this time, I figured it would be good to practice the new system when it barely mattered—the Democratic primary for a few local seats. I have to say it's more complicated and a whole lot less fun than going in person and chatting with the precinct workers, but it seems okay.

If people are honest.

I know mail-in voting somehow works well in Switzerland, but it still makes me nervous to rely on it here on a large scale. Election fraud is nothing new, and is possible no matter what system you use. My father used to tell stories of the days when votes were openly bought. But mail balloting does seem to me to be more open to fraud—particularly to coercion—than in-person voting. You can force or trick someone into voting a certain way a lot more easily when you can see what they're marking—or even mark it for them and force them to sign—and mail the ballot yourself, than in the privacy of a voting booth. How do we prevent that? Don't tell me there aren't plenty of unscrupulous people with that kind of power over others.

Our registration procedures have become very lax in recent years. According to a poll worker I know and trust, one person in his experience was mailed a ballot to vote in Florida, and was at the same time registered (and planning) to vote in New Hampshire. She had no idea she was even registered to vote in Florida; the best guess is that it happened automatically when she applied for a Florida driver's license. I see nothing in the process that would prevent her from voting twice, except her own honesty. I also don't see how it happened, since Daniel Webster (who is my favorite congressman because he was instrumental in making home education legal in Florida decades ago) assures us in this op-ed article that, unlike some states, Florida only sends mail-in ballots to those who request them. But something went wrong for this woman, and I foresee a lot going wrong all over the country, both by accident and by malicious intent.

Why, in some states, are people being mailed ballots who did not request them? All those extra ballots floating around is just asking for trouble. Really, if people are willing to go to work, and the grocery store, and doctor's offices, and restaurants, and bars, and parties—why are we pushing vote-by-mail instead of in-person?

In Florida, anyone who wants a mail ballot can request one, and I appreciate that service, but I am strongly convinced that the normal path for voting, the one that should be encouraged above all others, is in-person, on Election Day, where photo-identification and private booths do their best to ensure that a legitimate voter is casting a secret ballot.

Up front disclaimer: I write with little knowledge of the details of recent events in America. What I say comes from more than half a century of observation and analysis, including the intense conversations and scrutiny that came from being a high school student in the mid-to-late 1960's. The extent of my own, personal participation in physical, political activism was one political campaign demonstration and one anti-abortion event.

One of the most common questions I have heard coming from people observing riots and violence from the position of outsiders is, "Why are these people burning their own neighborhoods and destroying the very businesses they depend on?"

The answer, of course, is that "they" are doing no such thing.

Peaceful protests are turned into riots and looting when people get involved for whom riots and looting are IN THEIR OWN INTEREST. The community is not turning against itself: intentional agitators—those opposing the protesters along with those ostensibly supporting them—well-meaning but ignorant outsiders, and the guy who just wants that large screen TV, do not think of the neighborhood as "their community." They see civil disorder as opportunity, and don't hesitate to make opportunities happen for their own benefit.

That's the foundation for a riot. What happens next depends on how we react to those provocations. By "we" I mean anyone involved, from law enforcement to the original protesters to innocent friends and neighbors.

Unfortunately, it's all too easy for people who are scared, hurt, or angry to get pushed in a violent direction, or simply caught up in a mob, against what would be their better judgement in cooler times. Have you seen what cities look like after the home team wins a World Series or a World Cup? And those rioters are the HAPPY WINNERS.

I don't agree with the adage, "any publicity is good publicity," but I understand the unfortunate situation that peaceful actions do not generate the same kind of media attention that anger and violence do. If the protest in Minneapolis against the death of George Floyd had stayed peaceful, how many media outlets would have covered it? Would it have remained headline news to this day and spread its message all over the country, and the world? Would we still be talking about George Floyd and why and how he died? Sadly, we know that would not be the case.

Even if you believe the destruction was acceptable collateral damage in the quest for justice—which, I hasten to add, I do not—the job of getting out the word is done. NOW STAY HOME. (Aren't we supposed to be doing that anyway?) It's time to stop the violence, to stop spreading COVID-19 in areas already especially vulnerable to the disease, to heal and to build up the devastated neighborhoods, and to take advantage of opened pathways of communication while people are still willing to listen.

I have plenty of opinions on just about any subject, and if you're reading my blog, you know I don't hesitate to make them known. However, I rarely like to discuss politics directly. I also believe strongly in the institution of the secret ballot. Sometimes I don't even tell myself whom I'm voting for until I actually put pen to ballot.

So you won't know for certain whether or not I've voted for Bernie Sanders in the upcoming presidential primary, but I think he just said he doesn't want my vote, and who am I to deny him that privilege?

My Sanders-supporting friends can jump in here and tell me I've misunderstood him, or have heard only out-of-context quotes that aren't as bad as they seem.

But what I hear is Bernie Sanders, loud and clear, insisting that there is no such thing as a pro-life Democrat.

I've been a Democrat all my voting life, and campaigned for Hubert Humphrey even before I could vote. I vote my conscience—Democrat, Republican, sometimes parties you've never heard of—and let the chips fall where they may, but I've never seen any point in changing my party affiliation.

But I'm most definitely against abortion.

Actually, I'm pro-choice in most of life. Even in medical decisions, especially in those soul-wrenching decisions about when to withdraw life support. Our family has been there more than once, and I'm certain that loved ones are better equipped to make these choices than any doctor, judge, or regulation.

But the deliberate taking of the life of a healthy, innocent human being? That can't be anything other than murder. And, freedom-loving creature that I am, I acknowledge that laws against murder are a good thing.

Which, according to Mr. Sanders, is grounds for excommunicating me from the Democratic Party.

Fortunately, the Party is not a church, and he's not a priest. I'm still planning to vote in the primary.

I just don't know for whom.

I only know my choice is looking less and less like it will be Bernie Sanders, much as I think that if I actually knew him, I'd find enough reasons to like him as a person. Isn't politics depressing?

Socialism.

You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.

I'm not here to define socialism. I'm here to point out that no discussion makes sense when we haven't defined our terms. Or worse, when we all think we have defined them, and don't realize how different our definitions are.

When you consider the merits and evils of socialism, it makes a great difference whether your image of a socialist country is Sweden or Venezuela. For example, I have recently seen these comments, and others like them, on Facebook:

I am too old to live under socialism. I am addicted to luxuries like toilet paper, electricity, food, clean water and shoes.

I don't understand why Bernie Sanders supporters are so upset about the Iowa caucus. You wanted more socialism. Last night, you got more socialism: Third world tech, missing vote counts, chaotic rules, rigged elections. The only thing missing: food shortages.

Clearly the people who have posted these are operating under the Venezuelan picture of socialism. Knowing someone who is from Venezuela and still has family there, I'm with them.

However, this is a completely ineffective way to reach anyone who is operating under the Swedish picture. Whatever the reality of life in the socialistic Scandinavian countries is, the image of that life in many American eyes is idyllic.

Not, I hasten to add, for me. The high-taxes, high-services model can, perhaps, work pretty well when you have little government corruption, and—most important—a strong monoculture. When one is even a little different from the majority, it can be disastrous. Sweden is now having to acknowledge that their system cannot seamlessly absorb large quantities of people who are culturally far from Swedish, but even before the current influx of refugees, socialism was crushing Swedes whose beliefs did not fall in with the majority.

For example, many people praise Sweden's approach to day care, education, and parental leave—but it greatly favors conformity to the two-income family model, passing the costs on to those who are already sacrificing to live on one income so that their children can be reared directly by their families instead of through state services. The system will even take children away from parents who dare to challenge the government's educational services model. This is an unacceptable, basic human rights violation, but largely invisible to those who benefit from conforming to the system's expectations.

I personally fear Swedish socialism more than I fear the Venezuelan model, largely because I think it more likely to be implemented here. Certainly we are already well on that road. Even the socialist systems that work well enough—as long as one conforms to a certain culture—rely on a set of circumstances not easily duplicated. The Scandinavian socialist countries are wealthy, their governments are stable and relatively honest, and their culture has a strong history of Protestant-work-ethic values. There are many more countries and societies in which socialism has failed spectacularly than in which it has succeeded. For Sweden, or the United States, to descend into a Venezuela-like disaster is not impossible.

Be that as it may, when we try to argue with those who are pushing for more socialism in the United States, it's counter-productive to bring up Venezuela, Cuba, North Korea, or the former Soviet Union. They will only see that as a straw man fallacy. That's not what they mean by socialism, only perhaps failed socialism. What they want is what they see as successful socialism, and the only meaningful arguments can be to show where socialism is failing in the countries Americans admire. Most Swedes have toilet paper, electricity, food, clean water and shoes. What they lack is freedom.

Similarly, if you wish to argue that socialistic policies are a great idea, you must take into account all the places where it has failed and explain how that can be avoided. Otherwise you will be written off as simply ignorant.

No matter how good an argument may be, if it doesn't address what the other side sees as the real issues, it won't be effective.

Ramblings inspired by a glass of milk:

America, the land of Liberty. New Hampshire, the state with the motto, Live Free or Die. Sometimes I wonder what our Founders would think of our current willingness, even eagerness, to give up essential freedoms for (supposed) safety. But then I realize that people are much the same in every generation, so I'm sure they had to deal with plenty of the same kind of opposition.

Am I going to complain about the current attacks on our Second Amendment? Not now, even though I—with a lifelong dislike of guns—find the attempts to disarm American citizens appalling and frightening.

Not this time. Right now I'm standing up, as I have before, for the freedom to enjoy flavorful foods.

I insist that one culprit in our "obesity crisis" is that Americans are unconsciously craving the flavor of normal, healthy food. Food such as the "farm milk" we drink when we are in Switzerland: fresh from the cow, unpasteurized, unhomogenized, just real milk. Real milk that bears only a superficial resemblance to that of the same name purchased in an American grocery store.

At home, I love milk, and drink a lot of it. But I can only drink skim; whole milk sticks in my throat. Except in the form of hot chocolate, which is best with whole milk, even in America. In Switzerland, farm-fresh whole milk is absolutely delicious without any chocolate at all. (Granted, with a piece of dark Toblerone on the side, it is even better.)

There's no comparison between "real food" and that which comes from the average grocery store. Not only is grocery store food highly processed, but it is also deliberately homogeneous, so that there's no variation in flavor—milk is milk, orange juice is orange juice, apple juice is apple juice, chicken is chicken—instead of celebrating and enjoying nature's bountiful variety.

Don't get me wrong: there's a lot of benefit that comes from our mass-produced food, including lower prices. It is, indeed, what they call a First World problem. My objection is not to the availability of such food, but that it is crowding out the small, the local, the variety, the food of tremendous flavors. Worse, the awesome food—food that was plentiful as recently as 30 years ago—is now often illegal in America.

As with many roads to hell, this one is paved with good intentions. Safety is not the only issue—profit is another, as is the fickle American public—and safe food is important. But our approach to safe food reminds me of that old Chinese proverb, Do not remove a fly from your friend's head with a hatchet.

The school lunchbox is dead in Italy.

The Italian Supreme Court has ruled against parents who want to send lunch to school with their children. Their logic? Not eating the school-provided lunch is "a possible violation of the principles of equality and non-discrimination based on economic circumstances."

Even the United States isn't that crazy—yet—despite pushes in that direction by busybodies experts who worry that food from home might not be "good enough," and school-lunch providers who have a deep financial stake in forcing parents to buy their product.

Parents, naturally, are not happy.

Lorenza, who has two children at a Turin school, told a local TV station she spent more than €2,000 (£1,823) on school meals, more than her monthly salary. "My older daughter was not happy because the quality of the food didn't justify the cost, and also because of the hygiene issues with the canteen. "She would often complain that the cutlery was dirty, that the glasses were not particularly clean, or that there would be hairs on the plates," she said.

As with many news reports, this paragraph does not give enough information for us to know just how outraged we should be. Over what time period did this mother spend $2200 dollars? One month, as implied by the comment that the cost was "more than her monthly salary"? Annually per child? Over the entire school experience of all of her (possibly, though not likely, many) children?

Never mind. It doesn't matter. Even if the meals were totally free (where by "free" we mean paid for by other people, of course), it would still be an outrage.

School lunches may be a necessity for some children, who would otherwise not eat—though I've never been able to answer satisfactorily a friend's question, "Isn't that what SNAP (formerly Food Stamps) and WIC programs are all about? Why do we also need free school lunches?"

School lunches are certainly a convenience for busy parents—though there is no reason why a child of school age shouldn't be able to pack his own lunch.

But there was never any doubt in my mind that my own packed lunch was vastly superior to what was offered in the school cafeteria, and apparently our children thought so, too. Even if they often traded their carrot sticks to other children for cookies—at least some child was eating healthful food. I'm reminded of one family I know who qualified for free meals for their children. The children gave it a try, determined that the food at home was better tasting, more nutritious, and even more plentiful—and wisely opted out. At least here they had that option.

More to the point: whatever the Italian Supreme Court may say, being able to feed our children as we think best is a basic, human, family right—right up there with being able to birth, educate, and otherwise rear our children as we think best. As all totalitarian governments know, once you come between parents and their children, most other freedoms become meaningless.

For those families who cannot or will not handle these responsibilities on their own, we rightly make assistance available. That's called charity. But forcing that "assistance" on those who do not want it? That's called tyranny.

And the "principles of equality" the court found so important? Should we make everyone feed their babies formula because some mothers can't or won't breastfeed? Dumb down the school curriculum to the lowest common denominator? Put every child in daycare because some families need that service? Force every child into public school because some parents can't or won't provide private or home education? Make every woman give birth in a hospital because some babies need a doctor's care? Ban unpasteurized milk, orange juice, and cider because not everyone has access to safe sources of these delicious drinks? Forbid handmade clothing because not every mother can sew? Put handicapping weights on the feet of the best dancers to eliminate their advantage over the klutzes?

Oh, wait. Objects in the mirror are closer than they appear.

It's been a while since I posted in my Conservationist Living category, which is this post's primary classification, though I've assigned it to several others as well.

America is going to hell, right? Everybody says so. Including a whole lot of people who fervently believe there is no such place as hell, which is an interesting conundrum. But they all believe with equal fervor that we are going there rapidly. Believer or non-believer, left-wing or right-wing, we are convinced that we're in bad shape and on course to get much, much worse. What we disagree on is the attitudes, events, actions, and pathways that are taking us hell-ward.

Believe me, I'm not immune to such pessimism. Neither are you, so I'm going to tell you a small part of the story of Dave Anderson.

The Andersons are friends of our daughter's family, from their Pittsburgh days. Dave's success at building a good life for his family while reclaiming a worn-out strip mine and putting to good use many hundreds of tons of refuse every year was featured last month in this Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article.

I made the 45-minute drive to Echo Valley Farm this week because I wanted to meet the man who’d turned strip-mined land in northwest Beaver County into 26 grassy acres on which beef cattle thrive. Mr. Anderson had told me he revived his land by mixing hundreds of thousands of used paper cups from the Pittsburgh Marathon with manure, hay, banana peels and restaurant refuse.

You'll want to read the whole article to learn about the symbiotic relationship between the farm, needing nourisment, and both private businesses and local governments, needing waste disposal, that's a win for everyone involved.

It all works because there’s something in it for everyone. Mr. Anderson said that 14 years ago, the field over my shoulder produced 6,000 pounds of hay at the first cutting. The cutting in [the] same field last year brought 37,000 pounds.

Plus, the farm is a great place to raise kids.

I ask if it’s just the two of them and he says, no, he and his wife, Elaine, have six girls and a boy. They range in age from 10 to 24. All seven of them comprise Echo Valley, a bluegrass/gospel/Celtic band, that just played in Harrodsburg, Ky., Saturday night.

Several years ago—it was probably more than ten, though I'm finding that hard to believe—we visited the budding farm for one of their many social gatherings of food, music, and fun. Kids and animals were everywhere. The children were much younger then, of course, but they were already solid musicians. Here is a more recent video of the group.

and one of my favorites from earlier, just for fun.

Mr. Anderson, an inveterate reader who doesn’t own a TV, and who also was an air traffic manager until he retired last Friday, figured out how to turn desolate land into a lush farm that supports a family of nine with 30 head of beef cattle, six miniature donkeys, 40 laying hens, two turkeys, four guinea fowl, three geese, three ducks, two Australian cattle dogs and six pups.

Not to mention a number of cats, as I recall.

I hope this brightened your day. If America is, indeed, going to hell, people like the Andersons are pulling mightily in the other direction.

Permalink | Read 1680 times | Comments (4)

Category Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Food: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Conservationist Living: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

When I lamented my love/hate relationship with Penzeys Spices, one of my readers pointed me to an alternative spice source. I wasn't particularly looking for a new source at the time, having resigned myself to making do with grocery store spices except when Penzeys had a very, very special sale—which they seem to do every time Bill Penzey wants to point to a spike in sales as evidence that his customers support a particular political position.

But I checked out The Spice House and was blown away. I had not known the greater Penzeys story: It was Bill Penzey, Sr. who started the original Spice House company. His daughter took over the business, while his son, Bill Penzey, Jr., started his own spice company. Both companies have access to the old family recipes. The Spice House is smaller and more local than Penzeys, which they count to their advantage, all their spices still being prepared by hand in small batches, at their store.

The biggest difference between Penzeys and The Spice House is in politics. For all I know, the owners of the two stores share the same exact political views—or perhaps they are poles apart. I wouldn't know, because, unlike Penzeys, The Spice House makes a point of welcoming customers of all political persuasions, and keeping a very low profile themselves.

Here at The Spice House we are strictly a community of folks who like to cook; you will never get any lectures from us that include our personal agenda. We are just about the love of cooking and getting you the best possible ingredients to produce the most flavorful results!

Penzeys-quality seasonings without the side order of vituperation? I'm in!

My first order with The Spice House was just large enough to qualify for free shipping, because I'm trying to draw down my current spice stockpile, but what I've seen so far, I like very much. Here's a new blend that quickly became a favorite: Lake Shore Drive Seasoning: Gently hand mixed from salt, shallots, garlic, onion, chives, ground green peppercorns, scallions. My favorite alliums all together! I could only be happier if they had—without replacing this one—a blend that included all of the above except the salt, so I could add still more of the flavor to a dish.

I doubt The Spice House will totally replace Penzeys for me, as not all blends are available in both places. But it has certainly become the go-to store for my regular seasoning purchases.

I fell in love with Penzeys Spices the first time I walked into their Pittsburgh store, many years and ten grandchildren ago. What an enormous array of herbs, spices, and extracts of excellent quality, as well as their own superb spice blends! I couldn't say enough wonderful things about Penzeys, in person and here on this blog.

You may or may not have noticed that I don't do that anymore. My interactions with the company have left a bad taste in my mouth, and when your business is selling food ... that's not a good situation.

Once upon a time I stocked up on Penzeys products whenever we visited our daughter in Pittsburgh. I put myself on their mailing list, and in between times would sometimes place an order through the mail. But imagine my joy when Central Florida finally got its own Penzeys store! We generally visited once a month, to take advantage of the free spice coupons in the catalog, and of course we almost always made other purchases as well.

Ah, the catalog. In each one, Bill Penzey wrote an enjoyable little column about spices, food, cooking, and family. I used to like reading that, almost as much as I enjoyed the food & family stories contributed by customers. But gradually, that changed. Politics started to infuse the catalog, first in Bill's column and then in the customer stories he chose to include.

Well, I don't usually discriminate against great products based on the political opinions of the company. I continued to drool over the catalog, skipping Bill's column. When I did read it, I was usually sorry I had. We continued our monthly visits to the store, where even the employees rolled their eyes at the political turn the company was taking.

And then Penzeys closed our store.

I understand that companies must make difficult economic decisions and sometimes stores must be closed. I'm okay with that, even if it makes me sad. Their lease was up, and rents are high in the area they had chosen to open their store. What my anger flowed from was the implication on their sign that they would soon be opening a new store in the area, though I certainly was looking forward to that.

You see, in his political writings Bill Penzey consistently positions himself and his company as the defenders of the common people, the little guys, the poor and needy ... you get the picture. He's always denouncing people and businesses that make decisions based on what he perceives as selfishness and greed. Yet he decided to close a store and reopen elsewhere just to get his company out from under an expensive lease, leaving his employees—the little guys, the poor and needy common people—high and dry. They could not afford to wait for the opening of a theoretical new store: they needed jobs. Given all Bill Penzey has said about what other people should do with their money and in their own businesses, I would have expected his company to bite the bullet, forgo some profit, and at the least not close the existing store until a new one, nearby but in a less expensive neighborhood, was ready to provide jobs for their displaced employees.

They did not. That moves the scenario from necessary business decision straight to hypocrisy. And as it turned out, it has been four years since they closed, and there is still no sign of a Penzeys store any closer than Jacksonville.

On top of that, despite my many attempts at communication—before and after this event; whether contribution, compliment, or complaint; by e-mail or postal mail—I never heard back from Penzeys. It was worse than writing to a politician and expecting communication!

Since then, Bill Penzey's political rants (which now come to me by e-mail rather than printed catalog) have gone over-the-edge extreme. The hypocrisy, the hate-preached-as-love, would almost be funny—if it weren't so sad.

The following incident did make me laugh, at least until I started wondering what tax advantage the company might be angling for. Last Friday, the mailman delivered a box of excitement: my most recent Penzeys order. Penzeys packages often come with a freebie or two tucked in, such as sample-sized envelopes of herbs or spices (my favorite) or something advertising the store or one of Bill Penzey's pet causes. Here's one of the latter that came this time:

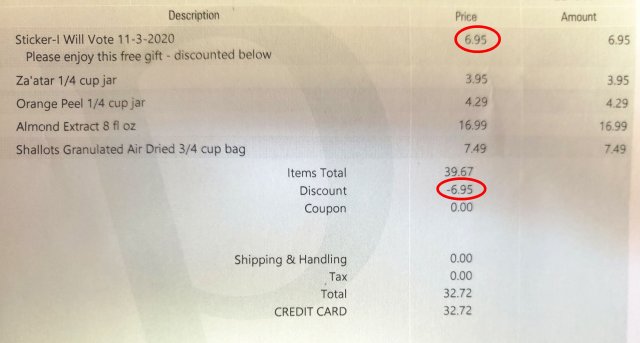

It's a sticker, no big deal except for the waste when it ends up in the landfill. What makes it bizarre is how it appeared on the packing slip, which you can see below, with some prices I've circled in red.

For this sticker, which I didn't order, they charged me $6.95, then "discounted" the price at the end. What kind of pricing is this? Who in his right mind would pay $6.95 for a sticker, let alone one not even worth sending to grandchildren? And what's the point? Some sort of shady accounting practice or tax benefit?

Amusing in a different way are the accolades Bill Penzey gives himself by first (1) making an extreme political statement, then (2) offering an extraordinarily good sale, 'way too good to pass up, then (3) bragging that his customers clearly endorse his political beliefs—just look at the spike in sales!

But do you know what? I still buy his spices. Not nearly as much, not nearly as often. As I said, the company now leaves a bad taste in my mouth. But the taste of the spices is still wonderful. I don't believe boycotts to be generally useful, and in most cases I choose businesses by quality and price without asking about politics.

Penzeys' reputation for quality is no doubt why they feel they can get away with repeatedly and consistently alienating half their customer base. It puts me in mind of what a math professor friend said about Harvard University years ago: The quality of education at the school has gone down significantly; students are no longer getting what a "Harvard education" used to mean. Harvard is living on its reputation. And that will be slow to die, because the Harvard reputation will still give Harvard graduates' résumés a great advantage over others. More importantly, it will continue to attract the best students, which will give them both the "iron sharpens iron" benefit and an unbeatable network of connections for the future. You can't live forever on reputation alone, but if you have once been great, you can fool yourself and others for a long time.

I believe Bill Penzey is fooling himself. As long as Penzeys' spices are perceived as superior—and many of them really are—even the spurned, denigrated, vilified half of his customer base will not flee en masse. But many—like some students who forgo applying to Harvard—may decide that the difference is not worth the cost. The love and the loyalty are gone.

Update 10/16/19: Note that this post has garnered enough comments to spill over past the first page. Click on the Next link to see the more recent ones.

I'd say the President and the Speaker of the House are acting like two-year-olds, but I have more respect for two-year-olds than that. That said, in their recent spat—in which the Speaker told the President that in light of the partial government shutdown he should postpone his State of the Union Speech or submit it in writing, and the President told the Speaker that in light of the same she couldn't use a military jet for her planned foreign travel but was welcome to fly a commercial airline—each made an excellent point.

The subject, "As Go the People, so Go the Leaders" has two meanings. One, that while we should be able to expect our leaders to be better in every way than the rest of us, that never happens, and can not realistically be expected in a democracy. For the record, I believe democracy to be the best form of government, and do not believe that our political system is broken, as so many are fond of saying. What is broken is our culture, especially our culture as seen through our media—and all too often we deserve what we get.

The second meaning is more to the point here. I'll give the Executive their Air Force One. But the Legislative Branch? The branch that is supposed to be made up of representatives of the American people? I'm sick of Congress exempting itself from the rules it imposes on the rest of the country, and the practices that further divide our representatives from the reality of American life. Let them fly the way the rest of us do. Preferably coach class.

And having a written State of the Union speech instead of a political grandstanding media circus? Sounds great to me!

Some of my friends predicted a Blue Wave. Some of my friends predicted a Red Wave. Instead, I awoke this morning to a sea of purple.

I'm good with that. I'm a purple kind of person, politically. I belong to a particular party only so that I can participate in the primary elections. Yesterday I voted for some Democrats and some Republicans. I won some races and lost others. Of one thing only am I certain: the victors will be neither as bad as I fear nor as good as I hope.

I'm also fine with what they're calling a "mixed government." No party should have an easy time pushing its own agenda: we lose the checks and balances that allow the voices of the rest of the country to be heard.

However, I do have a few words for the winners:

- If you won your race by a 51/49 margin, do not intone, "The people have spoken" and think you have a mandate for your ideas. Never forget that half your constituency do not want you as their leader.

- If you won by a landslide, I say the same thing. A rare 60/40 victory, or even an unheard of 90/10, does not mean you have the right to ignore the minority. Never forget that you are now as responsible for looking after their interests and considering their needs and values as you are those of the people who voted for you.

- Remember that you were elected to serve, not to be served.

That would make American great.

Today being the REAL Election Day, I voted. I can't say it was the pleasant experience it usually is. Oh, the poll workers were as friendly and as helpful as usual, but the room was chaotic and I left not feeling so confident about some of my fellow-voters. I write this now, before the results are known, so I can't be biased by the results, whatever they may be.

Several people seemed to be having procedural compliance issues. Now the voting procedure in Florida is easy: be registered, and show up with an acceptable photo ID with signature. There are other ways, such as a photo ID without signature plus some other ID with signature. Or voting a provisional ballot and having your signature matched with your voter registration signature. They really bend over backwards to make voting easy here. They also make it very clear before you go to vote what you need to bring with you to the polling place.

For just one example of the confusion, the man in front of me was insisting that they accept his driver's license. Normally, that's the easiest way: they can scan your license and you're in. But this man's license was from another state.

Poll worker: When did you move here?

Voter: Eight months ago. And I registered to vote.

Poll worker: But you didn't transfer your driver's license. You must do that within 30 days of moving here. This license is not valid.

Voter: Why should I get a new license? This one hasn't expired yet.

(In case you are wondering, this wasn't a language issue.)

At least those who believe that the mere act of voting is meritorious in and of itself will be happy. With all the other ways Florida has of casting one's ballot, and the fact that I usually vote mid-morning, the polling places are usually pretty empty when I arrive. Not this time!

I was taught to view voting as a civic duty, and have always believed that. I still do. It's almost a civil sacrament, the "outward and visible sign" of good citizenship. With that in mind, I have observed that Americans have made some of the same mistakes with regard to voting as the Christian Church through the ages had made with its own sacraments.

Ideally, the sacraments are made available to all Christians ("citizens") who are deemed to have sufficient understanding of and respect for what they are doing. Different churches disagree considerably on what constitutes sufficiency, but that's the general idea. Two extremes may be noted, however.

- Some churches, especially in the past, have greatly restricted the sacraments: to those of their own church, those who are of at least a certain age, those who have undergone sufficient instruction, those who have been thoroughly examined and been found to be fit, etc. They take very seriously the Bible's admonitions not to partake of the sacraments lightly—but by doing so have excluded many who should be welcomed.

- Some churches, taking seriously the idea that the effectiveness of the sacraments is based on God's grace, have thrown wide the doors with no concern that the participants have genuine faith or knowledge of what they are doing. Historically, this has resulted in politically- and economically-motivated, or even forced, "conversions," to the great detriment of the Church (not to mention the individuals involved).

As regards its secular, civil religion, America has certainly been guilty of the former. Today, however, we appear to have veered crazily toward the latter. The effectiveness of voting in and of itself is touted as enthusiastically as in the most egregious historical misuse of ex opere operato by the Church.

Everywhere, I am surrounded by the admonition to VOTE! Not a word about being educated on the issues and the candidates, not a word about considering the needs of others and the good of the country rather than one's own self-interest, not a word about casting an intelligent and wise vote—simply VOTE! Cast your ballot and let the magic of voting do its work.

Baptize a man against his will and he becomes a Christian. Require a man to attend Mass on Sunday, and it doesn't matter if he's a Mafia Don.

Quiz: How well can you tell factual from opinion statements?

This isn't one of those silly Facebook quizzes, like the one that purports to tell you what voice part you should sing based on personality questions—the one that told me I should be singing low bass. It's from the Pew Research Center, and consists simply of 10 political statements for you to classify as factual or opinion. I thought they were all obvious and scored 5/5 on the factual statements and 5/5 on the opinion statements. Alas, the "nationally representative group of 5,035 randomly selected U.S. adults surveyed online between February 22 and March 4, 2018" did not do so well: only 26% had a perfect score on the factual part, and 35% on the opinion section.

If you take the quiz (which does not require an e-mail address, signing in, or anything else intrusive), you'll get to see not only your results but a breakdown of the people who answered each particular question correctly, based on political party affiliation and how much they trust national news organizations. The first is particularly interesting, if somewhat depressing. Unfortunately for partisans, there's no evidence that Democrats are smarter than Republicans, or vice versa. Sometimes one party fared better, sometimes the other. What is clear is that both parties have a strong tendency to label statements consonant with their own beliefs as fact, and statements that they disagree with as opinion. This despite the clear instructions:

Regardless of how knowledgeable you are about each topic, would you consider each statement to be a factual statement (whether you think it is accurate or not) or an opinion statement (whether you agree with it or not)?

What I find find disturbing is the apparently lack of understanding that a statement of fact can be wrong. "I have red hair" is a statement of fact—one that happens to be false. So is "I like to eat liver" (also false). The latter statement is factual, not opinion, even though it states my opinion of the taste of liver. "Liver is disgusting" is an opinion statement, and my agreeing with it does not make it factual.

It seems we have carried "I'm right, you're wrong" to a whole new level.

In one of the early episodes of the TV show Monk, Adrian Monk's assistant, Sharona Fleming, explains, "I never vote; it only encourages them."

I believe that informed, intelligent voting is the duty of citizens in a democracy. I really do. But having arrived at (primary) Election Day, I'm inclined to sympathize with Sharona.

Take the school board race, for example. I don't need anything more to make me over-the-top thankful that my era of intimate involvement with the public schools is long over, but the priorities of this year's candidates reassure me that I would still be bashing my head against the wall it it weren't.

What are the hot-button issues for the candidates in our safe, mostly suburban school district? School safety, mental health counselling, vocational education, and getting rid of standardized testing. They're so consistent on this that the one guy who is a little different may well get my vote—despite his bizarre rant about how he doesn't want to carry a gun, as if he can't tell the difference between allowing someone with a carry permit to bring his own gun onto a school campus, and somehow requiring all teachers to carry guns. (To be fair, teachers are asked to do so many things besides teaching these days, I can understand his paranoia a little.)

I'm all for vocational education—in which America as a whole needs to do a much better job—but could we not have at least one candidate who is concerned about academics? Who will make a priority of offering our students a first-class, high-quality education? If their top concerns for our schools are safety and mental health issues, then it's not an educational institution we're running. I don't know what it is, but it's not a school.

The other races aren't much better. Looking through their campaign literature is an exercise in, "Nope, not that one. Not him. Not her. Certainly not that one. Oh, look, one who doesn't completely vilify her opponent, how refreshing."

If it's my duty to vote, isn't it someone's duty to provide candidates worth voting for?