I have no illusions that many of my readers will watch this video. Maybe no one at all. It's two hours long, and few of us have two hours to spare for a YouTube video. It's a discussion of human trafficking among David Freiheit (Viva Frei), Robert Barnes, and their guest, Eliza Bleu, a trafficking survivor and advocate. I managed to listen to it all by taking it in small bites and multitasking. Lengthy or not, the topic is important. They don't even try to deal with the more nuanced issues, such as "sex workers" whose participation is really, truly, consensual, and "slave wages" that turn out to be a family's best hope of escaping poverty. They don't even take on "legitimate pornography."

Sadly, I think this is a wise approach, if they don't want to make the mistake abortion opponents made: in that debate, too many people insisted on all-or-nothing, refusing to accept compromises that would have allowed abortions for cases of rape, incest, and where the child is so deformed that he would suffer and die soon after birth anyway. That approach was logical, in a theoretical, ethical sense—but arguing over the rare exceptions resulted in the door for abortion being opened wide and far. In the case of human trafficking, there is more than enough horror on which everyone but the perpetrators can agree; let's focus on that.

The interview is interesting from beginning to end, though that is a very poor word to describe something that can only be endured through a certain numbness and keeping the whole topic at a deliberate distance. The beginning, where Eliza tells her own story, is most interesting, especially to homeschoolers. If you're looking for another reason to hate the big social media companies, there's plenty of fodder in the later part of the video.

I'm frustrated that video is the medium of choice for so much information, especially current stories. I read so very much faster than I can listen, even pushing the video to higher speeds. Plus, anything good that is written has been through at least minimal editing, whereas with interviews, podcasts, and live streams, every um, uh, and rabbit trail remains. I find the written word to be much more efficient, usually much more dense in terms of information conveyed. But sometimes the more personal touch that can come through in a video is valuable, too.

In any case, as our choir director has taught us, it is what it is, and sometimes you have to adapt. I put this out here, (1) so I can find it again, and (2) in the off chance that someone may find it enlightening.

Liberty is meaningless when the right to utter one’s thoughts and opinions has ceased to exist. That, of all rights, is the dread of tyrants. It is the right which they first of all strike down. They know its power. — Frederick Douglass, 1860

When I was in school, my history classes went mostly in one ear and out the other without pausing to impact my brain along the way. I'm not sure how all my teachers but one managed to make such a fascinating subject dull, but they did. At least to me; it may be that those who were already interested in the subject managed to thrive. Don't get the wrong impression: I never received a grade lower than an "A" in any of those courses—I just didn't remember much of anything past the final exam.

Therefore I can't necessarily say that I knew nothing about Frederick Douglass until I went to the University of Rochester, where I encountered him every day. Sort of. Our dining hall was in the Frederick Douglass Building. That alone was enough to make what I've learned about the man since then stay with me. The learning process is a strange thing.

I'm still learning more. I ran into the above quotation just this morning. Since it was a Facebook meme, I did some research to make sure that both the quote and the attribution were correct. They are. Douglass was speaking in response to an incident in Boston, when a mob, supported by the governing authorities, shut down an abolitionist meeting. The speech, along with a good explanation of the context, can be found here: Frederick Douglass's "Plea for Freedom of Speech in Boston". It's not long, and I strongly recommending reading it.

I'd rather end this post here. But, sadly, I feel the need to include a reminder that Douglass was also an advocate for women's rights. Too many people have now (sometimes deliberately) forgotten the days when "man" was the general term for human beings of either sex, much as "duck" is the general term for a particular type of waterfowl, both ducks (female) and drakes (male). I don't want anyone feeling negative about this excellent and important speech because of an unwarranted reaction to Douglass's final sentence: "A man’s right to speak does not depend upon where he was born or upon his color. The simple quality of manhood is the solid basis of the right—and there let it rest forever."

Part 1 of the visit of our Swiss family is here, part 2 here.

At last, Christmas drew near, and we focussed our activities nearer home. Christmas Eve saw us in church, of course, with some of our guests pressed into service in our hand chime choir. Hand chimes are not nearly as beautiful as handbells, but they are what we had. We didn't even have a handbell choir until it emerged as a desperation move to give our choir a way to make music when rehearsing and singing were forbidden. In this we were oppressed, not by the state, but by our very own bishop, whose rules were far more draconian than the governments'. I had so looked forward to being able to share with our family the absolute beauty of our high church worship, especially on such a special day, but it was not allowed to be. Nonetheless, we were grateful to be permitted in-person services at all. We were there; God was there. And some of us went back later for the midnight mass.

cropped.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Credit for the above three photos Anke Cirillo of Three Point Photography

And then it was Christmas! Happiness is a house full of family.

After Christmas we boldly got together with our long-time friend and former choir director for one of our spontaneous music-making sessions. It's impossible to describe what a glorious outpouring of joy there is in these events. I do have a few recordings I treasure, but out of respect for the true musicians who don't always appreciate having their impromptu experimentations broadcast to the world, I'll leave it to your imagination. We had singing, piano, harmonica, viola, recorder, hand chimes, and all manner of percussion. If I could do this every night I know my mental state would take a drastic turn for the better. And the interaction between me on the tambourine and our granddaughter on the maracas was pretty good physical exercise, too.

We visited several playgrounds and natural parks, including taking the Black Point Wildlife Drive on the east coast. It's a favorite of ours, and a lovely place to see birds. On this trip, however, the more exciting views were of another sort:

And what's a trip to that part of the state without a stop at the Dixie Crossroads restaurant?

We continued to enjoy our final days of this visit, trying not to think too much about the upcoming long trip to Miami and the even longer trip across the Atlantic. And the 10-day quarantine awaiting them back in Switzerland. But they survived all that without catching COVID-19, and so did we. We are so grateful to Florida for welcoming our overseas family, to Switzerland for letting them come (and return), and to all whose efforts made this visit possible. I hadn't fully realized the toll these pandemic restrictions had taken on our mental health until we were reminded of what we were missing. I believe this visit came just in time, and I'm so glad we made the joyful choice.

This December visit seems more than six months distant, given that January and February brought us vaccines and the beginning of more freedom, at least in Florida. It would be April before the Northeast opened up enough for another healing family visit ... and that's a story for another post.

Permalink | Read 3963 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Being a Floridian, and one who has enjoyed several cruises, I was naturally intrigued by the following Viva Frei episode in which attorneys David Freiheit and Robert Barnes discuss Florida's lawsuit against the CDC's shutdown of the cruise industry. The video is just under 14 minutes long.

As I said, the story was of mild interest to me from the beginning. It was already on my "blog about this, maybe" list. However, it turns out to have a personal angle that makes it even more compelling. Unfortunately, I can't talk about it for privacy reasons, but it serves as a clear though pleasant reminder that no matter how nameless and faceless the machinations of government and business seem, there are real, everyday people behind them all. We forget that to our peril.

Last Sunday, Viva & Barnes revisited the story, reporting that the judge, instead of ruling on the case, sent both parties to mediation. (The relevant part of the video is 26:18 - 28:29.)

Here is another example of what a difference "spin" makes in news reporting. Barnes clearly sees the mediation order as an indication that the judge would rule in favor of Florida if he had to, and as a way for the him to let the CDC save face while keeping himself from being accused of "killing granny." However, most news articles I read have reported it as a setback for Governor DeSantis, and pointedly place the blame for cruise ships fleeing Florida, not on the CDC's restrictions, but on both DeSantis and the Florida Legislature for forbidding discrimination against people who have not been vaccinated.

I certainly hope that Barnes is right, and more accurate in his analysis of the judge's inclinations than he was of the judge's gender—though these days I'll admit the latter is a trickier call than it ought to be.

Part 1 is here. Now for more of our adventures during our December attempt at choosing joy and life amidst a pandemic-inspired focus on fear and death.

The eight of us did most of our venturing-outside-the-home together (being blessed with a car that seats that exact number), but occasionally we split up, as when two of us spent a day at EPCOT and the rest of us sought our entertainment at a classic American mini-golf course. Both groups had great fun. Credit goes to Disney for keeping their parks open and at the same time uncrowded so that the experience felt safe as well as fun. Remember that back then we knew much less about outdoor transmission (or lack thereof) of the virus, and people were nearly as scared outdoors as inside. The golf course was similarly comfortable.

Left: Congo River Golf; Right: EPCOT at night. Click to enlarge.

We also separated to give Janet and Stephan a chance to celebrate their anniversary on their own. They chose a hotel on Daytona Beach, and we joined them the next day for the chance to swim in the Atlantic Ocean on the first day of winter. Porter and I declined the swim, as it was 66 degrees, cloudy, and windy. That didn't stop the hardy Swiss, however! I didn't realize until we arrived that they had chosen a hotel on the same section of beach where I spent so many happy hours as a child—a five-minute walk from my grandparents' house. The coquina-built bandshell is much the same, and so is the ocean, but almost nothing else.

Closer to home, we visited the Orange County History Center, which thoughtfully made it possible to see the good stuff while avoiding the decidedly-child-inappropriate special exhibit of history's darker side. We picked out and decorated our Christmas tree, made cookies, and generally prepared for the holiday, which is not surprisingly much more fun with children around. We visited playgrounds, worked on various projects at home, swam some more, and sang and played music together.

Only twice in our entire month together did I feel the least bit uncomfortable with regard to COVID-19. The worst was at our local pizza party arcade, since we arrived at a time when a large party of people without masks crowded the place. Fortunately it was easy to return later.

The second time was at Sea World. I mean no particular criticism of the park, which clearly took precautions very seriously: taking temperatures, requiring masks, keeping even the outdoor stadiums at low, well-distanced capacity. But overall the park was more crowded than allowed for comfortable distancing, unlike our experience at EPCOT. However, this was on December 23, one of the busiest days of the year, one we'd normally have avoided like the plague. (Perhaps that analogy isn't the best one to use at this time.) The experience was overall delightful and certainly much more pleasant than it would have been in a normal year.

More to come.

Permalink | Read 1535 times | Comments (1)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

This is the post I started to write five months ago, but postponed to make sure everyone involved got through their quarantines and other impedimenta successfully.

I like to think that we've been more careful than most during this pandemic, though more due to the concern of our children (who apparently think we are "old") than our own. But when you're retired, and introverted, and not easily bored, staying home is a pretty easy option. We wore masks before our county made them mandatory, shopped only for what we deemed necessities, and used the stores' "senior hours" when we could. I'm also the only person I know who consistently washed (or quarantined) whatever we brought home.

But all that isolation, particularly the lack of physical touch, is hard even on introverts.

Hardest of all was cancelling our big family reunion scheduled for April 2020—coinciding with what was supposed to be the first visit home in six years of our Swiss family. Following close behind were missing our nephew's wedding, our normal summertime visit to the Northeast, and our long tradition of a huge family-and-friends Thanksgiving week of feasting and fun, all of which would have involved being with most of our American-based family. Plus the breaking my fourteen-year streak of travelling overseas to visit our expat daughter and her family (one year to Japan, thirteen to Switzerland).`

I know that doesn't begin to compare with the hardship endured by those who were forceably separated from loved ones who were sick or dying. But when the "temporary measures to keep our hospitals from being overwhelmed" turned into unending months of restrictions—with our hospitals so far from overcrowded as to be financially strapped due to underutilization—even normally compliant people like us began to chafe.

Even as we relaxed and let go of much of our fear, we remained vigilant in our precautions, for a very good reason: a light, not at the end of the tunnel, but a much-needed illumination in the middle of the tunnel. We needed to stay healthy, because...

The reunion remained off the table, due to onerous quarantine requirements imposed by the states the rest of our family live in. But thanks to much work on their part, and a state government more enlightened than most, our European family was able to visit us in December. Rarely have I been so happy to be living in Florida, which welcomed them with open arms. So of course did we! Mind you, I think the CDC was still recommending we wear masks all the time with visitors and stay six feet apart, but naturally that didn't last six seconds! A year apart from family is far too long, and that goes tenfold for grandchildren. Sometimes you just do what you have to do.

We did the risk/benefit analysis—and made the joyful choice.

Porter had to drive to Miami to pick them up, because so many flights had been cancelled. But he would have driven farther than that to bring them home!

We had been prepared to stay mostly around the house, just enjoying each other's presence. And at first we did a lot of that, since merely being in America was adventure enough for the grandkids. But they were here for a month, and most of the tourist attractions had reopened, albeit at reduced capacity, so we took full advantage.

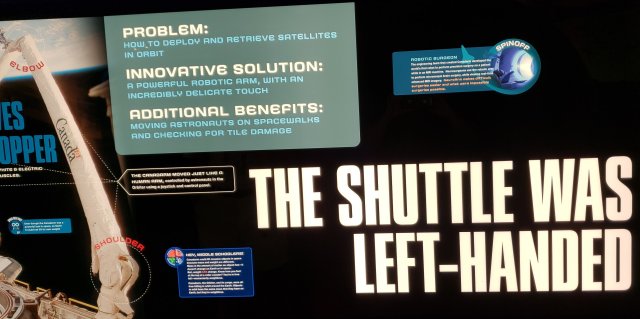

Kennedy Space Center was amazing. We were not the only visitors in the park, but at times it seemed like it. Sadly, some of the attractions were still COVID-closed, but there was certainly plenty to see. The following photo is for the lefties in our family:

One of the trips I enjoyed the most was to Blue Spring State Park, which was visited by more manatees than we've ever seen naturally in one place. The weather was perfect—that is, cold. Cold weather drives the manatees from the ocean and the rivers into the relatively warm water (about 72 degrees) of the springs. The air temperature made most of us keep our masks on even though that was not required except inside the buildings, since we discovered them to be very effective nose-warmers.

Another favorite activity was swimming. (Not with the manatees; that's no longer allowed.) The intent was for most of it to be in our own pool, and indeed it was, but there had been a glitch: We purchased a pool heater, knowing that our pool temperatures in December can dip into the 50's (Fahrenheit). However, the unit that was supposed to have been installed before our guests arrived was delayed again and again. Whether it was actually the fault of the pandemic is anyone's guess, but that's what took the blame. It finally arrived just a few days before they had to return to Switzerland. Until then, the children swam bravely, if not at length, in the cold water, and all of us enjoyed the (somewhat) heated pool at our local recreation center. And then they really appreciated our own heated pool for those last few days.

To be continued....

Permalink | Read 1473 times | Comments (1)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

So ... Canada is now saying, "It's not as bad here as in North Korea, or Nazi Germany." And we can say, "It's not as bad here as in Canada." Not exactly progress, is it?

As a mathematician I can say it is, actually—with a minus sign.

That was from May 7. Today we have this.

This is not sensationalism and fearmongering. Viva Frei is careful to see many sides of an issue. So am I, and I fully acknowledge that not everyone sees the same line separating civil disobedience from selfish thuggery.

Following the rules is necessary for a functional civilization.

Blindly following the rules is necessary for a functional tyranny.

Respecting one another is necessary for a functional humanity.

I'm going to leave it at that for now.

"Who Is in Control? The Need to Rein in Big Tech," from this past January's Imprimis magazine, deserves mention here. It's not one I would normally republish, not because I don't agree with it, but because the author is the senior technology correspondent for Breitbart News. He has the credentials to be heard, but Breitbart's biases make me as wary as CNN's do, and I know many of my left-leaning readers would see that and stop reading.

Don't. Please don't. What he has to say about the uncontrolled power of Google, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Amazon, and the like should concern everyone. Right now, it's conservatives who are feeling the flex of Big Tech's muscles, but the tech leaders could easily turn around and bite the hands that are currently feeding them. If you believe in freedom and democracy at all, this is worth reading and pondering.

Like most Europeans, my son-in-law, who is Swiss as well as American, has always wondered why I am so afraid of the misuse of governmental power, and not concerned about Google. I, in turn, don't understand how he can be so worried about tech companies while having no problem with a level of government surveillance and interference that would shock most Americans. I still think he's wrong not to be worried about excessive power in governmental hands, but I have to admit that he's right about Big Tech.

My response used to be, "Who cares if Google uses my data to target ads? I just ignore them, as I've always done with ads in newspapers (I usually don't even notice them) and on television." But that was then. That was before Facebook took down my 9/11 memorial post because it included a photo of Saddam Hussein. That was before it became obvious that Facebook was troubled by posts that even hinted that they might be about COVID-19. (Click image to enlarge.)

That was before I noticed how much Facebook and YouTube censor viewpoints they don't like. How careful one must be not to run afoul of their "algorithms." And certainly before Facebook, Twitter, Google, and Amazon proved that they are powerful enough to shut down the president of the United States, as well as a service (Parler) that welcomed Donald Trump's participation.

This may look as if it's about politics. It's not. It's about power. And it threatens everyone on every part of the political spectrum.

In January, when every major Silicon Valley tech company permanently banned the President of the United States from its platform, there was a backlash around the world. One after another, government and party leaders—many of them ideologically opposed to the policies of President Trump—raised their voices against the power and arrogance of the American tech giants. These included the President of Mexico, the Chancellor of Germany, the government of Poland, ministers in the French and Australian governments, the neoliberal center-right bloc in the European Parliament, the national populist bloc in the European Parliament, the leader of the Russian opposition ... and the Russian government.

Common threats create strange bedfellows. Socialists, conservatives, nationalists, neoliberals, autocrats, and anti-autocrats may not agree on much, but they all recognize that the tech giants have accumulated far too much power. None like the idea that a pack of American hipsters in Silicon Valley can, at any moment, cut off their digital lines of communication.

It is important to remember that the Web, as we know it today—a network of websites accessed through browsers—was not the first online service ever created. In the 1990s, Sir Timothy Berners-Lee invented the technology that underpins websites and web browsers, creating the Web as we know it today. But there were other online services, some of which predated Berners-Lee’s invention. Corporations like CompuServe and Prodigy ran their own online networks in the 1990s—networks that were separate from the Web and had access points that were different from web browsers. These privately-owned networks were open to the public, but CompuServe and Prodigy owned every bit of information on them and could kick people off their networks for any reason.

...[T]he Web was different. No one owned it, owned the information on it, or could kick anyone off. That was the idea, at least, before the Web was captured by a handful of corporations.

We all know their names: Google, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Amazon. Like Prodigy and CompuServe back in the ’90s, they own everything on their platforms, and they have the police power over what can be said and who can participate. But it matters a lot more today than it did in the ’90s. Back then, very few people used online services. Today everyone uses them—it is practically impossible not to use them. Businesses depend on them. News publishers depend on them. Politicians and political activists depend on them. And crucially, citizens depend on them for information.

Ah, the early days. We were early Prodigy users, and GEnie, before the Internet took off. Those were the days when it was easy to interact with famous people, because it was all so new and the numbers were small. GEnie's Education RoundTable was a great resource in our early days of homeschooling, and there I met Bobbi Pournelle, wife of science fiction writer Jerry Pournelle. We even arranged to meet when she came to Orlando, as did other of my ERT acquaintances. That was before we were warned against having meet-ups with people we only knew online, and it was a good deal of fun.

Big Tech has become the most powerful election-influencing machine in American history. It is not an exaggeration to say that if the technologies of Silicon Valley are allowed to develop to their fullest extent, without any oversight or checks and balances, then we will never have another free and fair election. But the power of Big Tech goes beyond the manipulation of political behavior. As one of my Facebook sources told me ... “We have thousands of people on the platform who have gone from far right to center in the past year, so we can build a model from those people and try to make everyone else on the right follow the same path.” Let that sink in. They don’t just want to control information or even voting behavior—they want to manipulate people’s worldview.

Consider “quality ratings.” Every Big Tech platform has some version of this, though some of them use different names. The quality rating is what determines what appears at the top of your search results, or your Twitter or Facebook feed, etc. It’s a numerical value based on what Big Tech’s algorithms determine in terms of “quality.” In the past, this score was determined by criteria that were somewhat objective: if a website or post contained viruses, malware, spam, or copyrighted material, that would negatively impact its quality score. If a video or post was gaining in popularity, the quality score would increase. Fair enough. Over the past several years, however—and one can trace the beginning of the change to Donald Trump’s victory in 2016—Big Tech has introduced all sorts of new criteria into the mix that determines quality scores. Today, the algorithms on Google and Facebook have been trained to detect “hate speech,” “misinformation,” and “authoritative” (as opposed to “non-authoritative”) sources. Algorithms analyze a user’s network, so that whatever users follow on social media—e.g., “non-authoritative” news outlets—affects the user’s quality score. Algorithms also detect the use of language frowned on by Big Tech—e.g.,“illegal immigrant” (bad) in place of “undocumented immigrant” (good)—and adjust quality scores accordingly. And so on.This is not to say that you are informed of this or that you can look up your quality score. All of this happens invisibly. It is Silicon Valley’s version of the social credit system overseen by the Chinese Communist Party. As in China, if you defy the values of the ruling elite or challenge narratives that the elite labels “authoritative,” your score will be reduced and your voice suppressed. And it will happen silently, without your knowledge.

If Big Tech’s capabilities are allowed to develop unchecked and unregulated, these companies will eventually have the power not only to suppress existing political movements, but to anticipate and prevent the emergence of new ones. This would mean the end of democracy as we know it, because it would place us forever under the thumb of an unaccountable oligarchy.

The author does have a suggestion, and I think it sounds reasonable. (I know my audience will not hesitate to let me know if I've missed something.) Some may think that I am against government regulation, but that's not true. I'm against unreasonable government regulation. (For my purposes, I get to define "unreasonable.") Most especially I am against regulations that fail to distinguish between large entities (in business, agriculture, education, medicine, and the like) and the small and individual. I don't know how to quantify "large enough" to need special regulation, but I have no doubt that our tech giants have crossed that line.

All of Big Tech’s power comes from their content filters—the filters on “hate speech,” the filters on “misinformation,” the filters that distinguish “authoritative” from “non-authoritative” sources, etc. Right now these filters are switched on by default. We as individuals can’t turn them off. But it doesn’t have to be that way. The most important demand we can make of lawmakers and regulators is that Big Tech be forbidden from activating these filters without our knowledge and consent. They should be prohibited from doing this—and even from nudging us to turn on a filter—under penalty of losing their Section 230 immunity as publishers of third party content. This policy should be strictly enforced, and it should extend even to seemingly nonpolitical filters like relevance and popularity. Anything less opens the door to manipulation.

I cannot say it strongly enough: This is not a left-wing thing; this is not a right-wing thing. This is a big thing. A thing we must all come to grips with.

I don't write these posts to frighten or depress anyone. But a number of my readers have higher priorities than chasing down news stories, so I like to raise awareness when I come upon something important, interesting, or even just fun. This one's not fun, but it is important.

Why should I care what's happening in Canada? Leave aside for the moment that Canadians, too, are human beings made in the image of God and therefore we should care about them, and that Canada is the huge neighbor covering our entire northern border and one of our major allies. We should also care about what's happening with our near neighbor because the United States is not as far from this creeping danger as we might like to think.

One of our daughters and several of our grandchildren have for years been taking lessons in karate. One thing I have learned from them is that the first, and possibly the most important, key to self-defense is awareness of your surroundings. Never forget that a far better source also proclaimed wisdom as an essential accompaniment to innocence.

Half a century ago our family discovered Ontario's Arrowhead Provincial Park. We had only intended to spend one night there on our way to Michigan, but were so enchanted we stayed for three. It was quite primitive at the time: there wasn't much to do, and the bathroom "facilities" were a latrine. But we were almost alone in the park; most of the other tourists were staying in nearby Algonquin Provincial Park, which was more developed and very popular. Never have I breathed air so clean and invigorating. More memorable than that, however, were the stars. Not in all the rest of my life have I seen such a display, and such a show, as we lay on our backs on a huge woodpile and watched shooting stars streak across the sky at a rate of perhaps one every two or three minutes. I knew then that if I couldn't live in the United States, I'd want to go to Canada. Later Switzerland moved ahead, and that was well before we had family living there. But Canada stayed a solid second.

Well, that was then and this is now. There are many reasons why Canada has slipped far down on my list, but the following video would be enough.

A government (Ontario's, in this case) went too far with its pandemic restrictions, and finally the citizens—including medical practitioners and the police—rebelled, forcing the leaders to back down on the most egregious of the new rules. That's good news, but be sure to watch to the end to see the clips of Ontario's authorities and their "this hurts me more than it hurts you but it's for your own good" act. And their "it's your duty to snitch on your neighbors" response.

Ontario is a province of 14.5 million people, and 650 of them are currently in intensive care units. This minuscule percentage has caused such panic that the provincial government's response was (among other things) to issue a stay-at-home order, to close playgrounds, boat ramps, and other outdoor recreational activities, and to authorize law enforcement to stop and interrogate any people caught outside of their homes. Canada takes enforcement of these rules very seriously: the fine for violating Quebec's 8 p.m. to 5 a.m. curfew, for example, starts at $1500.

Part of the problem is that Canada's health infrastructure is not good. An ordinary flu season overwhelms the ICUs. I've known for years that Canada's healthcare system is broken, despite the fact that it has its passionate defenders. (Much of my information comes from Canadian nurses, who fled to the U.S., bringing horror stories with them.) Even a bad system—healthcare, government, business, church, marriage—can look reasonable when times are good. It's times of crisis, pressure, and stress that reveal the truth and call into account the leaders we have elected (or been saddled with).

I used to look at historical happenings in other countries—e.g. Austria-Hungary 1914, pre-WWII Germany, Communist Eastern Europe, the Rwandan genocide—and smugly think, "That could never happen here, not now." However, the past year has shown that it can, indeed, happen here and now. We're not there yet, but we've come a lot closer, particularly in the area of what ordinary citizens will do to their neighbors.

American has no call to feel smug—or safe. We may not be as far down the road as Canada is, but it sure looks as if we are heading in the same direction. Should we panic? Despair? Absolutely not. But we'd darn well better be paying attention.

I've posted quite a bit already about and by David Freiheit and his YouTube channel Viva Frei. But he certainly deserves a part in this series, so here it is, along with some new (to here) videos.

David Freiheit is a Canadian lawyer in Montreal, who worked several years with a big law firm, then started his own commercial litigation practice. During this time his YouTube presence grew, and in 2018 he gave up his practice and took his YouTube channel fulltime. He calls his vlog (video blog) a VLAWG, because his video commentary on current issues from a legal standpoint is what really took off for him. I love seeing American politics from a Canadian point of view, and learning more about life in Canada, especially in Quebec. Occasionally one gets a chance to practice French, but the vlog is in English and Freiheit is good at providing translations.

His style is a little on the crazy side, but he makes legal issues and legal documents interesting, which qualifies him as a miracle worker as far as I'm concerned.

Although Freiheit pulls no punches he is also generally happy, positive, and willing to see more than one side of a situation. He retains his lawyer's caution and willingness to go beyond the surface of a story. Sadly, the pandemic—or more precisely, governmental reaction to the pandemic—is taking its toll on his optimism, but as with much these days, we live in hope that "this too shall pass."

Note: This is a caveat appropriate for all YouTube videos, but especially ones that touch on politics: you may want to avoid the comments. Freiheit is a reasonable and generally even-handed commentator, but not all his followers are so polite.

Another note: You may notice that he uses his own euphemisms for certain words. I don't mean for profanities—he's quite good at keeping his vlog clean without that—but for otherwise normal words that tend to upset the YouTube algorithm and lead to the demonetization or even taking down of videos. Words like "coronavirus," "COVID," and "fraud," for example, have at one time or another been YouTube no-no's. Sometimes he'll also just leave a legal paper or a tweet or letter up on the screen for the audience to read, since apparently YouTube is more likely to object to the spoken word than an image of words. The things you have to do for freedom of speech these days!

There are several different kinds of videos on Viva Frei, and he films in a few different locations. Many of his vlogs are recorded in his car, a concession to the pandemic reality that there's no quiet place in the house. Some are nonetheless done from his basement, and right now he is being quarantined in a family cabin because someone in one of his children's classrooms tested positive for COVID. He also vlogs while ice fishing, which I find both interesting and distracting—I tend to worry because even a New Hampshire native would consider the conditions very cold, and he often has bare hands!

My introduction to Freiheit's work was his legal analysis of current issues; even after all this time, I'm still tickled that he can make legal language and legal proceedings interesting. The following video about a lawsuit against Facebook is a good example of that kind, including a short explanation of class-action lawsuit, and it's less than 10 minutes from start to finish.

Here's another, also from his car, showing not so much legal matters as applying a logical legal mind to reveal the facts behind the news story—or in this case, the tweet. (Just over 10 minutes.)

Then there's his "Viva on the Street" series, in which he vlogs while walking along the streets of Montreal with one or both of his dogs, because walking a dog is one of the very few ways in which it is legal for a Québecois to be out after the "temporary, one-month" curfew was imposed back in mid-January. (Spoiler alert: the curfew is still in place.) Since one of his dogs has paralyzed hind legs, and the other is a puppy going blind, he actually spends more time carrying them than letting them walk, but so far the officials haven't fined him—as they've done to those who have been walking their cats, and the one intrepid woman who had her husband on a leash. Dogs only, please.

But I digress. Here's one of the "Viva on the Street" episodes about the curfew (11 minutes).

He also does live streams with American lawyer Robert Barnes, which are fascinating, but who has time to watch for two hours? I wait for the excerpts that he publishes afterwards. I'd post a sample here, but I'd rather not include more than three videos in an introduction. If you get interested in the channel, you'll find the live streams.

And there's more. All in all, it's a fascinating channel, with more videos than I can keep up with—or even want to. If you'd occasionally like to get out of your American news bubble, or your mainstream media bubble, or to know more of the stories behind the headlines, this is a good place to be.

For less in the way of politics and more on everyday life in Quebec, Freiheit has another channel, Viva Family.

Permalink | Read 2872 times | Comments (0)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] YouTube Channel Discoveries: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I like the Viva Frei video law blog, in part because although David Freiheit pulls no punches he is also generally happy, positive, and willing to see more than one side of a situation. But this pandemic—or more precisely, governmental reaction to the pandemic—is taking its toll on his optimism.

I haven't said much here about the horrendous rules now in place for anyone who dares try to enter Canada—Canadian citizens included—but I'm posting the following because, as Freiheit says, people need to know.

I've set the video to start part way through. The first story, about employees at a Canadian Tire store going vigilante on a man who was not wearing a mask, is definitely concerning. Here in Florida we had someone in a convenience store check-out line actually pull a gun on a woman who was standing too close for his comfort. But in the Canadian Tire event there is stupidity on both sides, and I think its inclusion distracts and detracts from the main story, in which the Canadian government is the problem.

In short, in the name of safety, the Canadian government has taken the authority to compel people, including Canadian citizens, to be taken off to undisclosed locations and detained for an indeterminate time without due process. Heinous enough, but more harrowing is that these people are not told where they are going, and their families are not told where they are going. What's more, once they arrive at their "quarantine hotels," they are not allowed to use social media, and not allowed to disclose their locations.

So there you go. Innocent people with every right to be in Canada, whisked off to detention facilities, and no one knows where they have gone, other than that government officials have taken them. They can't leave, and they can't tell the world what's happening to them. Presumably all this is done in the name of public health, in fear of COVID-19. (I can't, however, imagine how the communications blackout is contributing to anyone's well-being.) This means that in addition to being "disappeared" and alone, these people are likely sick and alone. Even in the best of times we all know how closely their families must watch out for people in hospitals and nursing homes, because if they don't, bad things happen. They just do. I've lost track of the number of such incidents I know about personally. What are the odds these people are getting good medical care? As you can tell from the news story, they're not even getting decent security.

I'm aware that some people reading this will find Freiheit a bit too excitable. As I said, he's always enthusiastic about what he says, but as the situation in Canada gets more and more oppressive, he's getting more and more upset.

Perhaps rightly so.

O. J. Simpson, Casey Anthony, George Zimmerman, Donald Trump ... pick your favorite villain. There's someone out there who you are certain "got away with murder." It rankles, doesn't it? Makes you doubt our system of justice. Me? I'm just as guilty, though I worry more about the uncounted criminals who "get off on a technicality" when everyone involved knows they're guilty—including their own attorneys.

In the court of public opinion, we are all vigilantes. And that's a problem.

We have a lawyer friend who has seen our criminal justice system from several angles, having served for years as a prosecuting attorney, and for years as a defense attorney. I well remember a somewhat heated discussion with him, which started when I mentioned that I like the British system, in which a defense attorney, if he becomes convinced his client is guilty, must step down. (As I understand it, that was at least the case in the past. For all I know it might have changed.) Our friend is a gentle, mild-mannered man, but he vehemently disagreed, insisting that even the most guilty person is entitled to the best possible defense his attorney can provide. Maybe that's why the British attorneys stand down, figuring they can't do their best if they believe their client guilty. Apparently American defense lawyers have no such inhibitions. At least not the good ones.

All that to say, when a lawyer takes on what we believe to be the "wrong" side of a case, that doesn't make him a villain. And when a jury returns a verdict we disagree with, that doesn't make them wrong. They're all doing their jobs, and vitally important jobs they are.

In litigation, sometimes even when you win, you still lose. — David Freiheit.

In the American justice system, one does not need to be proven innocent to be acquitted. Because "innocent until proven guilty" is a bedrock principle, the burden of proof is on the prosecutor, who must show the accused to be guilty "beyond reasonable doubt." Small wonder that We the People, inflamed by media coverage, believe we know better than those who have seen the evidence and heard the arguments. We want to see our version of justice done without any respect for or patience with the due process guaranteed every one of us. Yes, the system sometimes fails, sometimes makes mistakes; I've seen it fail among our own family and friends. But vigilante "justice" is a terrifying prospect. It's time to reprise A Man for All Seasons again.

Current society is taking vigilantism to new heights. It's long been true that many of those found not guilty in law courts have nonetheless had their lives ruined (or even ended) by the opposite verdict from the court of public opinion. Now, however, the "String him up!" reaction extends not simply to the former defendant, but even to his attorney, as you can see in the following video.

If you are thinking of becoming a lawyer, and you are so sensitive to the thoughts of others that you sometimes require protection from them, you probably want to find a new line of work. — David Freiheit.

I never had aspirations of becoming a lawyer; I don't think I have the right personality. But even I can see that what this unnamed law school did to attorney David Schoen—rescinding a teaching offer in fear that Schoen's previous job as an attorney for President Trump would make some students and faculty feel uncomfortable—is doing a tremendous disservice to the students they hope to prepare for legal practice. Not to mention to society as a whole. Don't take my word for it; Freiheit says it better.

People don't seem to fully appreciate how dangerous a practice this actually is. — David Freiheit.

I'm beginning to sound like a mother: How many times do I have to tell you...?

I said it in my review of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. I said it again in "We Can Do Better," my reaction to the political theater idea that one should fight illegal behavior with illegal behavior. If you resort to evil to fight evil, don't claim the moral high ground.

Yet Time magazine is doing just that. Brazenly. Proudly.

A friend sent me this link to an Internet Archive (Wayback Machine) record of Time's February 4 article, "The Secret History of the Shadow Campaign That Saved the 2020 Election." I include both links because (1) the Time article may disappear behind a pay wall, or just disappear altogether, or (2) the article may be altered beyond recognition, à la Orwell. Maybe I'm being paranoid, but then again, maybe it's time for a little healty paranoia.

The article is long. At first, only the length made me doubt that its source was the Babylon Bee. Alas, no. If someone can prove to me that this is not an actual Time article, please do!

I'll admit it took me a while to finish reading, fascinating as the story is; I got bogged down by my own mind's refusal to believe what I saw. Now that I've read it all, I say, most remarkably, that I believe it—because of its source. Not that I trust Time magazine all that much, since I think it has become more openly biased, as well as less interesting than it once was. But when a left-wing publication reports something extremely negative about left-wing actions, I believe it's time to sit up and take notice. Just as I do when the shoe is on the other foot with a right-wing publication.

It's hard to report interesting stories when news sources are so biased. If I find something in a right-leaning publication, my left-leaning friends will dismiss it, probably unread. Ditto my right-leaning friends with stories from a left-leaning publication. Hence my delight with this story from Time, despite its appalling nature.

I was not surprised that my favorite Canadian lawyer was also blown away by the Time article. He explains it well in just under 22 minutes. You could read the article in less time, and I recommend it—but this is more fun, and I appreciate the clarity his legal mind brings to the verbiage.

I was reminded of the famous quote from the Vietnam era, "We had to destroy the village in order to save it." Not wanting to include that without checking its origin and veracity, I found a much better quote in this Bloomberg article on the subject. It is from the Atlanta Daily World, in 1940, making the point that fighting facism abroad was no excuse for suppressing dissent in America.

We won’t save democracy by killing it ... and we won’t make American democracy worth saving by destroying it in the so-called attempt to save it.

With the Fifth Amendment to our Constitution now joining the First and Second under attack, it's time for a brief review of the first ten, otherwise known as the Bill of Rights.

Amendment I

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Amendment II

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed.

Amendment III

No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

Amendment IV

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Amendment V

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

Amendment VI

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.

Amendment VII

In Suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise re-examined in any Court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

Amendment VIII

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Amendment IX

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

Amendment X

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

That's the bare bones; I leave analysis of these amendments as an exercise for the reader.

Just for fun, here are a few Sporcle games (roughly in order of diffculty) to help keep the bones of these amendments (and more) fresh in our minds.

What does it say when a Canadian lawyer is more concerned about violations of the U. S. Constitution than we are?

This one's only 11 minutes, and important. Slightly off-color in a couple of places, but no grandchildren for whom it matters will be watching this, anyway.

He who denies the Constitutional rights of my worst enemy denies them to me.