Amongst the devastating consequences of the Russo-Ukranian War is the disappearance from public eye of the power grab by Canada's Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, and his tyrannical handling of the Freedom Convoy protest in Ottawa.

Actually, a few European politicians did make note of it, calling out Trudeau for his hypocrisy in condemning Russian president Putin while trampling the rights of his own citizens back home. But largely that is yesterday's news.

So today I remember.

This beautiful 14-minute tribute by JB TwoFour (about whom I know nothing but this) bought tears to our eyes as we saw the familiar scenes replayed: the love, the joy, the unity of Canadians in all their diversity, and the support from other nations. Followed, alas, by replacement of the friendly interactions with local law enforcement by an irrational show of force from the government and imported police agencies.

`

(Yes, the misspelling of "Israel" also brought tears to my eyes, but that's just me.)

May history remember the Freedom Convoy as the turning point in Canada's return to sanity, respect for basic human rights, and constitutional protection for its citizens—instead of the minor footnote Prime Minister Trudeau and his supporters are counting on.

Permalink | Read 1120 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Freedom Convoy: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The first step in taking control of a nation is the simplest. You find someone to hate. ... You will find that hate can unify people more quickly and more fervently than devotion ever could. — Brandon Sanderson (Elantris)

Hatred is not an emotion that is foreign to us. Its presence in the world does not surprise me. What I find shocking is how easy we are manipulated into hating.

No one has to convince me to root for the Ukraine in the current conflict with Russia. After all, I'm a child of the Cold War, when the Soviet Union was always our number one enemy. In this case, they are obviously the invaders, perpetrating atrocities, and even threatening nuclear war. We remember Georgia, Crimea, Belarus, and ask, "Where will it stop if it doesn't stop here?"

But two thoughts give me pause.

First, the level of anger and hatred I see, directed against anything Russian (even harmless Ukrainians with Russian-themed businesses in the U.S.), exceeds reason—as I have seen increasingly on other issues in recent years. We are in grave danger of losing sight of the essential humanity of the Russian people, much as the people of Germany once lost sight of the essential humanity of their friends and neighbors.

Second, while the flame of anger arose naturally in our hearts, it has been and is still being unnaturally accelerated into this disastrous conflagration. Politicians, corporations, educational institutions, news organizations, social media, celebrities of all sorts, our own friends—the push is on to view the Ukraine as totally innocent victims and Russia as completely irrational, evil villains. Merely to suggest that Russia might have had legitimate fears and concerns that led to the move to "liberate" the Ukraine, or that the Ukraine might not be completely free of corruption and illegitimate actions, is to bring down the wrath of all who want to see (or who want us to see) this as a battle between absolutely good and absolute evil.

Even if that were true—and nothing in this world has that kind of clarity—it's bad policy. Unless you really want World War III.

But here's what's really concerning me: I am convinced that if "they"—used metaphorically, not specifically—wanted the completely opposite reaction, they could just as easily have engineered that instead. You don't need to posit a conspiracy behind the power of this behemoth conglomeration of government, media, academia, financial institutions, entertainment, big businesses, Big Tech, and ordinary peer pressure. Ideas themselves have power, and when all these very powerful entities align to push an idea, it becomes almost irresistible.

The beginning of resistance is to step back and ask, "Where did I get this idea? What is driving my response?"

We interrupt the story of our trip to Chicago to bring you something as beautiful as it is heartbreaking.

S. D. Smith, author of the Green Ember books, wrote:

I’m never sure what to say when world events are so intense and the words of an ordinary children’s author from West Virginia on social media feel so unnecessary. “Stay in your lane,” I tell myself. ... So, while ordinary men kissed their wives and children and turned to fight to protect their homeland from invasion, I wrote. I wrote thousands and thousands of words—in private—on a story that I’ve been working on for many months with my son. I kept at it while a new war in Europe intensified and drew the attention of the world. ... Though it feels relatively unimportant, I think creating and sharing soul-forming stories is of great long-term value. My lane is an avenue that goes straight through the hearts of children God made and loves and intends for his kingdom of light. No small thing. It’s a good little lane. So I write on.

Composing choral anthems is John Rutter's "good little lane." It's no surprise that his response to the tragedy in the Ukraine was to write music. He has made his A Ukrainian Prayer available to choral directors for free, with the suggestion that they make a donation to a relief organization serving the Ukrainian people.

Our choir sang it in church today. Based on the comments we received afterwards, the congregation appreciated both Rutter's music and the fact that we sang it at this time. I'll admit that both the alto and the tenor parts were weaker at the beginning than they had been in rehearsal, due to the fact that the two of us were unexpectedly hit in the emotional solar plexus as we started to sing—and I'm told we weren't the only ones.

Here's not-our-choir, with Rutter conducting. The video starts at the beginning of the piece, but if you want you can go back to the beginning and hear Rutter's commentary. This is sung in Ukrainian; the literal translation is "Lord, protect Ukraine. Give us strength, faith, and hope, our Father. Amen." Our choir sang the English version.

As our own choir director said, "It's not every musician who can just round up 300 of his closest friends to try out his composition."

Bonus for those who know: See if you can spot the point where I did a double-take and discovered our grandson's secret life as an English chorister.

Are you a person who prays?

Are you praying for the Ukraine, its people, and its leaders? Good. They need it, obviously and desperately.

But are you also praying for Russia? Are you praying for Vladimir Putin and his advisors?

I can't speak for any other traditions of prayer, but for Christians our responsibility is crystal clear: In addition to other Biblical precedent, we have a direct command from Our Lord to love and pray for our enemies.

If that isn't good enough, consider that the Russian people didn't ask for this. If we rightly fear domination of the people of Ukraine by Putin and the Russian oligarchs, we know that the Russians have been living that life all along.

Our sanctions may convince Putin to withdraw his forces, or they may drive him into desperate actions and alliances that will come back to bite us hard. That's not clear yet. What is definite is that they have tanked the Russian economy, and the Russian people are heading into financial hardship of a kind that has passed out of the living memory of our own country.

If their suffering is not enough to convince you to pray for them, consider what happened in Germany after World War I, when the winners of that conflict made certain that the German economy would be completely devastated.

Have I convinced you to pray for the Russians? Now, how about President Putin? It is so easy to fear him, and to hate him!

For Christians, again the command is clear: we must love him, and pray for him. (We don't have to like him.) Regardless of how we feel about him, he is as valuable in the eyes of God as we are. And if, as we'd like to believe, he were less worthy of our prayers, that would only mean he needs them more.

But if that's not enough, we must pray for Putin for our own safety's sake. (Did you catch the nod to A Man for All Seasons?) He's a man in command of a large and powerful nation, with his finger on the nuclear button. We all know from experience how much damage the last two years of pandemic isolation have done to people's mental health. From all accounts, Putin has taken this isolation to an extreme. If he was unstable before, what of now?

What's more, in our collective response to his invasion of the Ukraine, we have been backing him into a corner with no way to save face. We seem determined to defeat him utterly and humiliate him, forgetting that cornered bears are exceedingly dangerous. Finding a win-win situation is not capitulation; it's wise diplomacy, and much more likely to lead to a lasting peace.

I don't know how this dangerous and tragic situation should properly be handled. I don't know if we are being Neville Chamberlains or if we are being driven by the fear of making his mistakes into making more disastrous mistakes of our own. I don't see a Winston Churchill on the horizon.

I do know that the one thing we can do is to pray. For the Ukraine, and for Russia. For NATO, for the European Union, and for all the world leaders who don't know what they're doing and are doing it very enthusiastically.

When we were in Chicago recently, our first meal was at the amazing Russian Tea Time restaurant. It was a special occasion; if we lived in Chicago, the expense would make our visits rare. But if I were there now, I'd make a point of taking in another of their wonderful Afternoon Teas. Whatever we may think of the recent actions of Vladimir Putin, it makes no sense to penalize our Russian neighbors. This is the letter we received from the owners of Russian Tea Time.

Dear RTT patrons and friends,

We are heartbroken by the recent news; our thoughts and prayers are with those who are affected by this inhumane and despicable invasion. We do not support politics of the Russian government. We support human rights, freedom of speech, and fair democratic elections.

Украинцы (Ukrainians), the world is with you, the world is behind you. Stay strong, our hearts are with you!

The past two years have been so very hard on restaurants; they don't need any more grief.

Besides, you never know who it is you're actually affecting. The owners of our favorite place for sushi in Central Florida (now, alas, no longer in business) were Vietnamese, not Japanese.

The owners of Russian Tea Time are Ukrainian.

Permalink | Read 1510 times | Comments (2)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Travels: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Food: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I woke up this morning at 4:00, troubled by the news Porter had delivered when he came to bed about midnight last night. Life has been emotionally exhausting on so many fronts in the last two years that it can be a struggle to remind myself that we are among the most blessed and least troubled people in the world. Pain works that way.

Arising, I went in search of news, and was greeted by this instead. It was livestreamed at midnight, and is from the church we visited when we were in Chicago. (Mea culpa—I know I have yet to write about that wonderful trip.)

It is not likely to be a prayer tradition of many of my readers. But it was infinitely better for my mental and spiritual health than a news report—full of fear and adrenaline and necessarily of limited accuracy—would have been.

It's nearly an hour long, but if you want to know the truth behind the origins, organizers, goals, and strategies of Freedom Convoy 2022, this Viva Frei interview with Ben Dichter is well worth your time, even if you don't watch it all. No rants, no anger, just a calm, informative interview with a well-spoken official representative of the Convoy.

I fully intended to post something lighter today, but history has no pause button.

Anyone receiving a cancer diagnosis, or answering the phone to learn of a loved one's fatal auto accident, or having his home and belongings destroyed by fire, flood, or storm, knows how suddenly the world as he's always known it can be obliterated.

In the past two years, much of the world has experienced a lesser version of this lesson. Here in Florida, we have been greatly blessed by a less-heavy-than-most governmental hand on our pandemic response, but we've still suffered business closures, job loss, postponement of essential medical procedures, educational disruption, supply chain problems, and a whole host of mental health issues. It's been a disaster that took everyone by surprise, though other states and other countries have suffered much more.

In the blink of an eye, a simple executive order at any level of government can take away your job; close your school; shut your church doors; kill your business; deny you access to health care, public buildings, restaurants, and stores; forbid family gatherings; lock you in your home; stop you from singing; and force you and your children to submit to medical procedures against your will.

It astonishes me how many people are okay with this. At one point I was even one of them.

Canada has now taken this to a higher level.

It is clear from watching about 20 hours of livestream reports from Ottawa (there's a lot more if you have the endurance to watch), that the anti-vaccine-passport protest called Freedom Convoy 2022 is most notable for its peaceful unity-in-diversity—along with keeping the streets open for emergency vehicles, allowing normal traffic to move in areas away from the small immediate protest site, keeping the streets clean of trash and clear of snow, complying when the court ordered them to cease their loud horn blowing, and having a happy, block-party-like atmosphere.

Elsewhere, the unrelated-except-in-spirit protest at the Ambassador Bridge border crossing in Windsor, Ontario had already been ended peacefully by court order and the bridge reopened.

Why, at that point, did Prime Minister Justin Trudeau decide he needed to invoke, for the first time ever, Canada's Emergencies Act, designed to give the government heightened powers in the case of natural disasters or other situations of extraordinary and immediate danger? Here are some quotes from a BBC article about it.

[Trudeau] said the police would be given "more tools" to imprison or fine protesters and protect critical infrastructure.

Just what this means is not detailed, but the following is crystal clear. Bold emphasis is mine.

Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland said at Monday's news conference that banks would be able freeze personal accounts of anyone linked with the protests without any need for a court order.

Vehicle insurance of anyone involved with the demonstrations can also be suspended, she added.

Ms Freeland said they were broadening Canada's "Terrorist Financing" rules to cover cryptocurrencies and crowdfunding platforms, as part of the effort.

You can hear Freeland's speech here—if you can stomach it.

Let that sink in.

As someone said, "Justin Trudeau does not sound like Adolph Hitler in 1936. But he sounds an awful lot like Adolph Hitler in 1933." Nazi Germany did not get to extermination camps in one step.

I have funds in a local bank that is based in Canada. I have written positively about the Freedom Convoy. Does that mean Canada now thinks it has a right to my money? Can they reach into Florida and grab it, much as Amazon can, if it wishes, reach into my Kindle and yank an e-book I have purchased? We've made an inquiry with the bank's lawyers, but have yet to hear back.

Also from the BBC article:

The Emergencies Act, passed in 1988, requires a high legal bar to be invoked. It may only be used in an "urgent and critical situation" that "seriously endangers the lives, health or safety of Canadians". Lawful protests do not qualify.

And finally,

Critics have noted that the prime minister voiced support for farmers in India who blocked major highways to New Delhi for a year in 2021, saying at the time: "Canada will always be there to defend the right of peaceful protest."

Hypocrites much?

Charitable giving is a tricky thing. It's not enough to be generous; it's also important to be sure your money is going where you intend it, and is doing actual good instead of lining the pockets of drug pushers, thieves, and/or tin-pot dictators.

As a society, we're not all that good at giving to recognized, established charities, but let some new cause or tragic event take our fancy, and we pour out money like water, generously and carelessly. Recent events have been an object lesson in why it's not only foreign dictators who stop charitable gifts from getting to the intended recipients.

I had, of course, heard of the organization GoFundMe, which is used to organize fundraising campaigns for various causes. I have never had any dealings with them, myself—and now I think I never will. Trust, once broken, is very difficult to recover.

A GoFundMe project was set up to support the Freedom Convoy 2022, and quickly raised over 10 million dollars (Canadian). After releasing about a tenth of that, however, GoFundMe pulled the plug, claiming the organizers had violent intentions and as such violated their Terms of Service. (Never mind that after watching some 20 hours of unscripted, unedited livestream video from the protests, I've seen no evidence at all for such a claim; indeed all the evidence points to the contrary.)

You know those Terms of Service that we never read? It turns out they matter. GoFundMe, apparently, can pull the plug at their own discretion, without recourse.

[With my propensity for word play, it is SO tempting to switch out two of the letters in GoFundMe. But I will refrain. Obviously I have been listening to too much Gordon Ramsay. Besides, I know I'm not the only person to have thought of that one.]

Initially, GoFundMe said that donors had 14 days to request a refund (or until the 14th, I'm not certain anymore, and the site has changed since I first read it); otherwise all the money donated would be given to a "recognized charity" acceptable to both GoFundMe and the organizers of the blocked account. After an uproar, however, they changed that to automatically refunding all donations. So that's as good as we can expect, I guess. But it leaves me with zero faith that I can trust GoFundMe with my money.

Next chapter: Enter GiveSendGo.

I'd never heard of GiveSendGo, but they are an established fundraising platform that offered to step into the breach.

Viva Frei, my much-mentioned favorite Canadian lawyer, spent some time looking into GiveSendGo and gave it this review.

Almost immediately, the Freedom Convoy campaign on GiveSendGo garnered even more money than they had raised on GoFundMe.

From this point on, the story gets fuzzy, as rumors fly, and I'm not sure what to believe, but this is what I can make of it:

The Canadian government obtained a court order to freeze the campaign's assets. GiveSendGo is an American company and did not take kindly to that action, responding that the Canadian court lacks proper jurisdiction.

GiveSendGo was then hit by a Denial of Service attack, but still managed to continue to take in funds for the work of the truckers.

This was followed by an attack by hackers who redirected the GiveSendGo URL to a bogus site, and allegedly stole donors' personal information.

Then a Canadian bank (TD Bank), which was holding some of the money that had been released, froze the account.

And that's all I know so far.

Not true. I do know one more thing—lawyers are going to win big, whoever loses.

I've heard some complaints that there is a lot of "foreign money" in those accounts. While that may conjure up images of shadowy Russian or Chinese espionage, my impression is that the foreign supporters are much closer to home: cheerleaders from the United States, New Zealand, Australia, the United Kingdom, and Europe supporting their Canadian brothers and sisters in a campaign close to their own hearts.

Charitable giving is a tricky thing. That's no reason not to give, but it is sobering to know that even in a Western, democratic, and supposedly civilized society, governments, governmental agencies, and large private corporations are misappropriating our gifts.

Our Culture of Fear could be the title of a post on the last two pandemic years, but not this time. As much as COVID hysteria has scarred our children, school hysteria may be even worse. What have we done to the psyches of this captive, vulnerable population?

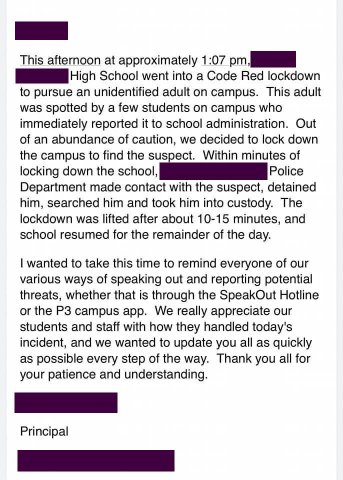

Yesterday our local high school students experienced a "Code Red lockdown." Why? Because some students reported the presence on campus of an "unidentified adult."

Word of caution: Very little information has been forthcoming from any news reports I have been able to access, so it's likely that there are factors I know nothing about. However, had the person been carrying a weapon or been in any other way particularly dangerous, I'm sure it would not only have been in the news, but in the headlines.

Here's an e-mail that was sent out to parents, redacted to protect the guilty. (Click to enlarge)

I know this school. Our children attended there, and we put in thousands of hours of volunteer time. There are over 2500 students on a very large campus. How anyone could have picked out an "unidentified adult" is beyond me. When I was there, more than 90% of the students and most of the teachers could not have identified me. I would park my car, walk into the school, wave to the teachers, say hi to the students, and get on with my work. No fuss, no guards, no need to sign in, just a friendly neighbor welcomed into the school community.

How things have changed! If I were to do that today, apparently I would be detained, searched, and taken into custody.

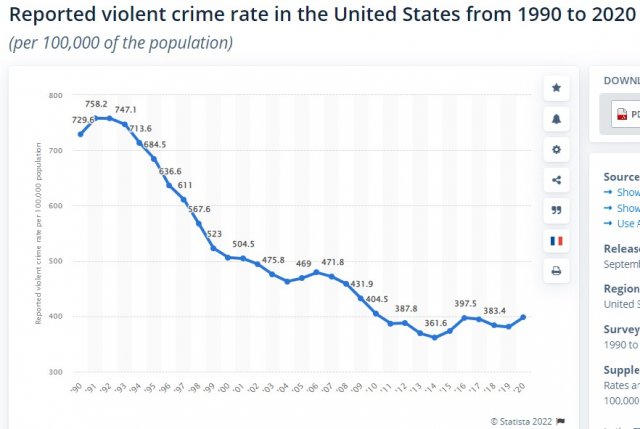

Before you lecture me that "It's not the 90's anymore; life is much more dangerous now," remember that the 90's were the peak of violent crime in the last half century. You can see that in this graph, from statista.com. (Click to enlarge)

Crime is 'way down, and fear is 'way up. School parents have reported that their children were absolutely terrified. I'm not sure I wouldn't have been myself, because a "lockdown" is a "lock in" and students can't get out. I'm not fond of being trapped, particularly when I have no idea that there isn't something really terrible going on.

Just as in our present pandemic situation, we are not paying nearly enough attention to the relative danger posed by extremely rare events that endanger children, and the damage a culture of fear does to their mental health.

Just yesterday I encountered the idea of how our primitive behavioral immune system fuels the bizarre fear, disgust, loathing, and anger that accompanies the COVID-19 vaccine debate, which I wrote about in my review of Norman Doidge's excellent article on the subject.

Today I ran headlong into a prime, and terrifying, example of just that, in a New York Times opinion piece by Paul Krugman, entitled "What to Do With Our Pandemic Anger." In my innocence, I assumed the article would be about the mental health crisis that has arisen from nearly two years of restrictions on normal human interaction.

I couldn't have been more wrong.

You may or may not be able to access the article—with the Times I find no rhyme nor reason as to when I can, and when I can't—so I'll quote a bit of it below and you can get the idea.

First, a reminder of what Doidge said about how the behavioral immune system [BIS] has hijacked our reason.

Many people’s mental set for the pandemic was formed early on, when the BIS was on fire, and they were schooled by a master narrative that promised there would only be one type of person who would not pose danger—the vaccinated person. Stuck in that mindset when confronted by unvaccinated people, about half of whom are immune, they respond with BIS-generated fear, hostility, and loathing. Some take it further, and seem almost addicted to being scared, or remain caught in a kind of post-traumatic lockdown nostalgia—demanding that all the previous protections go on indefinitely, never factoring in the costs, and triggering ever more distrust. Their minds are hijacked by a primal, archaic, cognitively rigid brain circuit, and will not rest until every last person is vaccinated. To some, it has started to seem like this is the mindset not only of a certain cohort of their fellow citizens, but of the government itself.

And now for a taste of what Krugman has to say.

A great majority of [New York City's] residents are vaccinated, and they generally follow rules about wearing masks in public spaces, showing proof of vaccination before dining indoors, and so on. In other words, New Yorkers have been behaving fairly responsibly by U.S. standards. Unfortunately, U.S. standards are pretty bad. America has done a very poor job of dealing with Covid. ... Why? Because so many Americans haven’t behaved responsibly. ...

I know I’m not alone in feeling angry about this irresponsibility.... There are surely many Americans feeling a simmering rage against the minority that has placed the rest of us at risk and degraded the quality of our nation’s life. There has been remarkably little polling on how Americans who are acting responsibly view those who aren’t ... but the available surveys suggest that during the Delta wave a majority of vaccinated Americans were frustrated or angry with the unvaccinated. I wouldn’t be surprised if those numbers grew under Omicron, so that Americans fed up with their compatriots who won’t do the right thing are now a silent majority. ...

I don’t claim any special expertise in the science, but there seems to be clear evidence that wearing masks in certain settings has helped limit the spread of the coronavirus. Vaccines also probably reduce spread, largely because the vaccinated are less likely to become infected, even though they can be. More crucially, failing to get vaccinated greatly increases your risk of becoming seriously ill, and hence placing stress on overburdened hospitals. ... You don’t have to have 100 percent faith in the experts to accept that flying without a mask or dining indoors while unvaccinated might well endanger other people—and for what? I know that some people in red America imagine that blue cities have become places of joyless tyranny, but the truth is that at this point New Yorkers with vaccine cards in their wallets and masks in their pockets can do pretty much whatever they want, at the cost of only slight inconvenience. ...

Those who refuse to take basic Covid precautions are, at best, being selfish—ignoring the welfare and comfort of their fellow citizens. At worst, they’re engaged in deliberate aggression—putting others at risk to make a point. And the fact that some of the people around us are deliberately putting others at risk takes its own psychological toll. Tell me that it doesn’t bother you when the person sitting across the aisle or standing behind you in the checkout line ostentatiously goes maskless or keeps his or her mask pulled down. ... Many Americans are angry at the bad behavior that has helped keep this pandemic going. This quiet rage of the responsible should be a political force to be reckoned with.

For someone who admits being no expert, Krugman is far from reluctant to make pronouncements based on questionable data. To his credit, he attempts to direct this "simmering rage" to political action, but the tone of the article is straight from, and speaks directly to, the behavioral immune system's primitive response of fear, disgust, and loathing. That cannot end well.

Believe it or not, I have left out the most vitriolic statements, which I deemed unnecessarily distracting.

Permalink | Read 1411 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] 95 by 65: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Only a few times in my life have I felt this close to history-in-the-making. The Apollo 11 moon landing. The fall of the Berlin Wall. Those were great events. Others were both great and heatbreaking, like the Prague Spring of 1968. I sure hope the Freedom Convoy 2022 ends better than that did.

We're finding Viva Frei's live broadcasts from Ottawa both fascinating and fun. And incredibly encouraging. The only sad part is how much misinformation is out there in the ordinary news media, giving a negative impression of the protest. But we have watched a lot of Viva's unscripted, unedited, livestream from the streets of Ottawa, and I've never seen such a happy, peaceful, clean, friendly, and respectful protest. These people are angry, right enough, but the anger does not show in their behavior or their attitudes. Well, except for the "F-Trudeau" signs, which is literally the only objectionable thing I have seen in all our hours of watching.

Most wonderful to see is the people from all over Canada, of multiple races, ethnic origins, religions, socio-economic groups, and occupations interacting so happily together. I've observed more hugs than in a week of visiting our grandchildren. I absolutely loved the report of some Québécois who declared, "We were Separatists, but after this we are no longer!"

Personally, I would go absolutely crazy from all the noise, but even so they have a good deal of support from local Ottawans, with reports of people bringing the truckers not only verbal encouragement but fuel, food, water, and offers of hot showers.

Social media, news media, and reading public comments on about anything can bring me to the brink of despair for society. This has been an amazing antidote.

Here's yesterday's 3+ hour stream. He's planning another livestream today, this time with his family. I'll post that link when I see it; you can also check out his YouTube channel to see when it goes live.

And here's a much shorter 13-minute video including interviews with a couple of Indigenous protesters.

The world is watching. A Kiwi who currently can't go home because of coronavirus restrictions reported that even New Zealanders are feeling that they've been pushed too far. They're watching Canada, they're supporting the protest, and hoping it spreads around the world.

It was 20 years after the Prague Spring before Czechoslovakia was free again. It has been over 30 years since the Tiananmen Square massacre, and the Chinese people still live under tyranny. Canada, you can do better.

Stay strong, stay peaceful, and remember to vote when you get the chance!

You will hear soon about our wonderful trip to Chicago, but current events are taking precedence today.

I hate crowds. All my senses are hyper-sensitive, and I'd go crazy in one of those cultures where people like to be close to your face and touch you frequently. So—not a good candidate for the thrill of the crowd. Times Square on New Year's Eve is not for me.

More than that, I have a healthy fear of the mob mentality. People do stupid things in groups that they would never do without the urging and peer pressure of the mob. You will not be surprised that I am very leery of participating in any kind of political demonstration, child of the sixties though I may be.

Actually, I'd brave the crowds to show my support for a good cause, and I have done so once or twice, but even the most peaceful demonstrations these days are vulnerable to infiltration by those whose goal is to cause trouble. Whether from fringe "friends" of the cause, enemies determined to discredit the demonstrators, or mere opportunistic looters, things can go bad quickly, and the risk of getting caught up in them is real.

All that said, part of me would really like to be standing in Ottawa with Canada's truckers and their Freedom Convoy.

It started in British Columbia, sparked by Canada's new rule that any truckers crossing the border from the United States must show proof of COVID-19 vaccination.

You really shouldn't mess with the people who transport food and other essential goods, especially when your country is already having supply chain issues.

The fed-up truckers started a convoy from British Columbia, across most of Canada to the capital city of Ottawa. Along the way the convoy grew, as more and more truckers, and other supporters, joined. It turns out that truckers aren't the only ones who are "mad as hell and not gonna take this anymore" (3.5 minutes, language warning).

Despite that appropriate clip (from a movie I know nothing about), these "mad as hell" protesters are incredibly friendly and peaceful. I don't know what you may have heard about the Freedom Convoy, but the reaction of the media has been ... interesting. First they ignored the protest, and when it finally got so large they couldn't ignore it, they tried to demonize it, calling the participants "racist, misogynist, white-supremacist, insignificant radical fringe elements," and accusing them of all sorts of objectionable behaviors.

So on Monday, David Freiheit (Viva Frei) drove from Montreal to Ottawa to see for himself, and document his experience in a livestream. Yesterday, I made it through 2.5 hours of video, to the point where his camera gave out. Then I went to bed, figuring to write this post in the morning.

I awoke to another three hours of video, because his camera had merely run into a brief issue that was soon fixed. That was more than I could handle, but I did watch the beginning, the end, and several samples in between.

It's a livestream, unscripted, unedited, simply showing his experiences as he walked the streets of the city and interacted with the people. He specifically sought out evidence of the negative reports. According to the news, there had been Confederate flags (in Canada?) and swastikas, along with desecrations of memorials.

Freiheit found no such thing, nor had any of the people he interviewed seen them. He did find one person who said someone had let the air out of her tires, and a report of a window accidentally broken by someone's waving flag. And one of the memorials spoken of had had some flowers put at the base, and a bouquet of flowers put in the statue's hand. The only objectionable thing I saw was a number of signs expressing a rude sentiment all too familiar in demonstrations when Donald Trump was president, with Prime Minister Trudeau's name substituted for Trump's. I did see a rather clever twist on the "Let's go Brandon" theme: Let's go Brandeau.

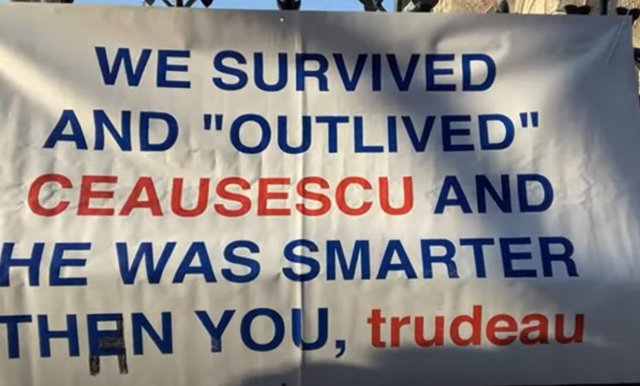

Speaking of signs, here's my favorite.

It shows how young Freiheit is—he was born in 1979—because he said he didn't understand it. None of us who were adults in the 1980's can forget the atrocities of Romania's infamous dictator, Nicolae Ceaușescu. These are, no doubt, the sentiments of a Romanian refugee shocked by the situation in "free, democratic" Canada.

It's also my favorite sign because someone noticed and corrected "then" to "than."

As far as I could tell, people may be angry about the government's policies, but they mostly seemed thrilled to get together with like-minded citizens and express their opinions. It could have been a block party. Smiles, hugs, excitement. Mutual respect between the demonstrators and the police. No litter on the street—the protesters made an effort to keep it clean. And they also shovelled the sidewalks! No rioting, no looting, no violence, no evidence of the bitter hatred so prevalent in recent protests south of the Canadian border. I knew there was a reason I've always liked Canada. They deserve better politicians, and certainly better policies.

You don't have to take my word for it; you can sample the streams yourself.

Part 1 (2.5 hours)

Part 2 (3 hours)

I found it exciting to watch, to be a part of it if only virtually, and to know that the event has been nothing like the news reports have portrayed it. May it stay the happy, if determined, protest that it is, as time goes on and people get more tired, cold, and frustrated.

If I had to live or work near Parliament Hill in Ottawa, I would quickly get tired of the sound of blaring truck horns, which sliced through my head even on the video. And no one can be happy about the traffic jams, even though long lines of trucks have been blocked from entering the city, in order to keep roads open for emergency vehicles.

I hope Canada's politicians quickly come to the realization that these people are also Canadian citizens they are sworn to serve, and learn to listen with respect. It's time to let the truckers—and everyone else—get on with their business.

The line between truth-telling and fear-mongering may be thinner than I'd like to believe.

I legitimately criticize most popular media outlets and others whose profits are driven by making people upset and afraid: I haven't seen such irresponsible journalism since the late 60's and early 70's. And yet I repeatedly write and share posts that I myself find frightening, because I think they highlight important information. If fear and panic are unhelpful, so are ignorance and denial. So I'll continue to publish information that I believe needs to be more widely known, trying not to be incendiary about it.

David Freiheit, my favorite Canadian lawyer/journalist, has given me gold mines of information about the legal aspects of current events. When I first began listening to his Viva Frei YouTube shows, one of the things that attracted me to him was his calm, balanced approach to events. I miss that. Now, after two years of pandemic stress, he's a bit edgier and angrier. But who can blame him? He lives in Montreal, where the provincial and federal governments continue to make unreasonable, unscientific, and inhumane intrusions into the lives of its people—far worse than anything we have had to endure. So please be patient with his anxiety; what he says is almost always eye-opening.

Below is a short clip from the full show that I will embed further on. This clip is only a minute and a half long, and if you don't find frightening both this use of children for propaganda purposes and what the children say with such enthusiasm, perhaps a study of 20th century history is in order. Or a reading of Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. Or a chat with someone who fled to the United States from a totalitarian country.

Here's the full video (12.5 minutes) of which the story of the children is just a sidebar. I've been referring to Florida as a "free state" given what I consider to be our relatively reasonable response to the pandemic, but this Miami judge proves that we are hardly monolithic in our actions and opinions. Note that the issue is not so much the judge's desire to insist that all potential jurors be vaccinated, nor even his insulting, demeaning, and incendiary language, but a legal problem: "These judges are rendering decisions based on evidence that has not been adduced and that is not how the court system works."

In case you don't watch the video but are curious about the "insulting, demeaning, and incendiary language," this is what the judge wrote in his ruling, which was on the face of it a simple postponement of a trial because the defense counsel did not want the jury pool limited by vaccination status.

It is the Court's belief that the vast majority of the unvaccinated adults are uninformed and irrational, or—less charitably—selfish and unpatriotic.

Even if you completely agree with the judge, the children, and the teacher, these stories should send shivers down your spine.

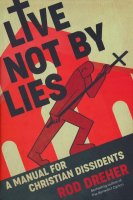

Live Not by Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents by Rod Dreher (Sentinel, September 2020)

Live Not by Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents by Rod Dreher (Sentinel, September 2020)

My previous book having been Brandon Sanderson's Oathbringer, this book's 256 pages might have made it seem like a beach read.

Not by a long shot.

I was struck by how much Live Not by Lies reminded me of The Fall of Heaven, although they are two very different books with very different subjects. The latter details Iran at the time of the 1978 revolution, while this book is largely based on stories from the survivors of Communism in Russia and Eastern Europe. What do they have in common? The warning that it CAN happen here. America is not so far off from totalitarianism as we naïvely think.

There always is this fallacious belief: “It would not be the same here; here such things are impossible.” Alas, all the evil of the twentieth century is possible everywhere on earth. — Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago

This was certainly the fallacy I believed in.

When I was a child, Nazi Germany was a very near memory for my parents, and the horrors of Communism an ever-present reality. But I knew for certain that it couldn't happen here and it couldn't happen now, because America was free and the democracies had grown beyond all that totalitarian stuff. True, I was forced in school to read 1984 and Brave New World, but such situations were as alien to me as the farthest galaxies. Ah, the optimism of youth.

Did I say youth? If you'd asked me five years ago I would have pretty much felt the same way. But the last few years have shown just how quickly radical change can happen.

Enter Live Not by Lies. Dreher was inspired by the stories and concerns of those who escaped totalitarian societies (largely from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union) only to see frighteningly similar patterns in present-day America. He is careful to distinguish what he calls "hard totalitarianism" with its secret police, gulags, and material deprivation, and the sneaky, but effective, "soft totalitarianism" that threatens us today. He comes down very hard on the Left, but neither does he spare the Right. Evil is most effective when it uses both halves of the nutcracker.

As indicated in the title, Live Not by Lies is written for Christians. But it would be a great mistake for others to pass it up for that reason. The most effective resistance to the hard totalitarianism of Nazism and Communism came from diverse coalitions of dissidents, and that's just as important now. These are dangers that affect us all.

It's not a totally satisfying book, the second half being less powerful than the first—at least if I judge by the relative number of passages I highlighted. I could include a great number of quotations in this review, but I'm not going to. Live Not by Lies is only $4.99 in Kindle form. Give up one fast food meal and get a book that just might open your eyes and strengthen your spine.

The following, rather long, excerpt from the introduction explains well the form and scope of the book.

Part one of this book makes the case that despite its superficial permissiveness, liberal democracy is degenerating into something resembling the totalitarianism over which it triumphed in the Cold War. It explores the sources of totalitarianism, revealing the troubling parallels between contemporary society and the ones that gave birth to twentieth-century totalitarianism. It will also examine two particular factors that define the rising soft totalitarianism: the ideology of “social justice,” which dominates academia and other major institutions, and surveillance technology, which has become ubiquitous not from government decree but through the persuasiveness of consumer capitalism. This section ends with a look at the key role intellectuals played in the Bolshevik Revolution and why we cannot afford to laugh off the ideological excesses of our own politically correct intelligentsia.

Part two examines in greater detail forms, methods, and sources of resistance to soft totalitarianism’s lies. Why is religion and the hope it gives at the core of effective resistance? What does the willingness to suffer have to do with living in truth? Why is the family the most important cell of opposition? How does faithful fellowship provide resilience in the face of persecution? How can we learn to recognize totalitarianism’s false messaging and fight its deceit?

How did these oppressed believers get through it? How did they protect themselves and their families? How did they keep their faith, their integrity, even their sanity? Why are they so anxious about the West’s future? Are we capable of hearing them, or will we continue to rest easy in the delusion that it can’t happen here?

A Soviet-born émigré who teaches in a university deep in the US heartland stresses the urgency of Americans taking people like her seriously. “You will not be able to predict what will be held against you tomorrow,” she warns. “You have no idea what completely normal thing you do today, or say today, will be used against you to destroy you. This is what people in the Soviet Union saw. We know how this works.”

On the other hand, my Czech émigré friend advised me not to waste time writing this book. “People will have to live through it first to understand,” he says cynically. “Any time I try to explain current events and their meaning to my friends or acquaintances, I am met with blank stares or downright nonsense.”

Maybe he is right. But for the sake of his children and mine, I wrote this book to prove him wrong. (pp. xiv-xvi)

I'll let Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn have the last word.

After the publication of his Gulag Archipelago exposed the rottenness of Soviet totalitarianism and made Solzhenitsyn a global hero, Moscow finally expelled him to the West. On the eve of his forced exile, Solzhenitsyn published a final message to the Russian people, titled “Live Not by Lies!” In the essay, Solzhenitsyn challenged the claim that the totalitarian system was so powerful that the ordinary man and woman cannot change it. Nonsense, he said. The foundation of totalitarianism is an ideology made of lies. The system depends for its existence on a people’s fear of challenging the lies. Said the writer, “Our way must be: Never knowingly support lies!” You may not have the strength to stand up in public and say what you really believe, but you can at least refuse to affirm what you do not believe. You may not be able to overthrow totalitarianism, but you can find within yourself and your community the means to live in the dignity of truth. If we must live under the dictatorship of lies, the writer said, then our response must be: “Let their rule hold not through me!” (pp. xii-xiv)

Permalink | Read 1657 times | Comments (0)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Last Battle: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]