Innovation on Tap: Stories on Entrepreneurship from the Cotton Gin to Broadway's Hamilton by Eric B. Schultz (Greenleaf, 2019)

Innovation on Tap: Stories on Entrepreneurship from the Cotton Gin to Broadway's Hamilton by Eric B. Schultz (Greenleaf, 2019)

This is the book I've been waiting nine years to read. Well, it's almost that book: Apparently, this amazing man's story, of which I was hoping to learn more, got left on the cutting room floor. No matter. Actually, it does matter, but I'm sure Eric will tell the story eventually, and in the meantime, Innovation on Tap has plenty of interesting tales.

A priest, a rabbi, and an imam walk into a bar....

Oops. Wrong story. But this book is set in a bar; the premise that provides its structure being that entrepreneurs as diverse as America itself—from Eli Whitney, who was born before we became a country, to Lin-Manuel Miranda, who is still making headlines—have gathered together in a bar and are swapping stories.

Innovation on Tap invites you to come on in, find an empty bar stool, and eavesdrop. Learn a little about business, learn a little about American history, and have fun!

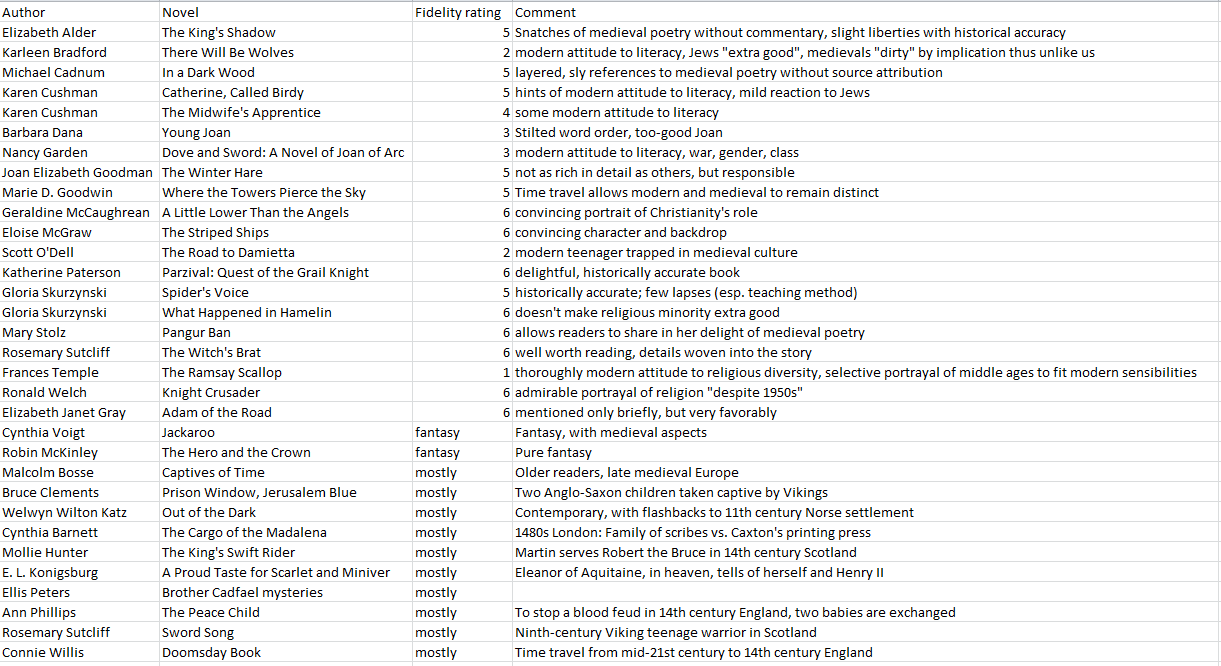

Here's the table of contents:

PART ONE—MECHANIZATION

- Eli Whitney: Accidental Entrepreneur

- Oliver Ames: Riding the Perfect Storm

- Against the Odds: Social Entrepreneurship in the Early Republic

PART TWO—MASS PRODUCTION

- King Gillette: Mass Production in an Age of Anxiety

- Mary Elizabeth Evans Sharpe: The Instinct to Do

- John Merrick: Building a Great Institution

- Willis Carrier: Mass Production Meets Consumerism

- Charles “Buddy” Bolden: The Sound of Innovation

PART THREE—CONSUMERISM

- Elizabeth Arden: A Right to Be Beautiful

- J. K. Milliken: Community in a Model Village

- Alfred Sloan: America’s Most Successful Entrepreneur?

- Branch Rickey: Prophet or Profit?

PART FOUR—SUSTAINABILITY

- Stephen Mather: Machine in the Garden

- Emily Rochon: Giving Voice to the Environment

- Kate Cincotta: Creating Climate Entrepreneurs

- Viraj Puri: Plants Are Not Widgets

PART FIVE—DIGITIZATION

- Brenna Berman: Building a Smarter City

- Jean Brownhill: A Community of Trust

- Brent Grinna: Quietly Building an Amazing Network

- Jason Jacobs: A Cheerleader for Community

- Guy Filippelli: From Battlefield to Cybersecurity

- Meghan Winegrad: Intrapreneur to Entrepreneur

Conclusion: A Model for Innovation and Community

Lin-Manuel Miranda and Hamilton

Most of these names meant little to me before I read Innovation on Tap, the primary exception being Eli Whitney, whom I wrote about in "Sometimes Old Family Stories Are True." I learned a lot. Some of what I learned was scary—especially in the section on consumerism; no one likes feeling manipulated—but I enjoyed seeing the human face of business.

Thanks to the ability to copy text from the Kindle version of the book (which at the time was on sale for 99 cents!), the quotes are a little more extensive than they might have been had I needed to type them all in by hand. Thanks, Eric!

The crisis at the turn of the twentieth century became how to keep giant, automated factories from oversaturating their market with goods. The solution to this problem defines the third entrepreneurial theme, consumerism, a fundamental change in America from a land of sober and frugal citizens defined by what they produced, to a land of ravenous consumers defined by what they purchased. (Introduction, p. 7)

Winners are those who become skillful at situating themselves in a supportive network. Education, intelligence, courage, grit—all are secondary factors. The entrepreneurial experience in America, no matter the period, is built on this cornerstone: The stronger the community, the greater the chances for success. From Eli Whitney to Mary Elizabeth Evans to Lin-Manuel Miranda, a strong personal network is the most striking attribute and powerful resource of a successful entrepreneur. (Introduction, p. 13)

Catharine [Greene] extended her home and hospitality to Whitney while he regrouped. In turn, he made himself useful through odd jobs, including the redesign of a tambour embroidery frame that Catharine had found difficult to use. This inconsequential act would soon have historic implications. ...

With few good crop options available, some Southern farmers began to plant short-staple cotton in the 1790s, hoping a process would be developed to make it salable in quantity. ... Raising a crop destined to rot in the field or warehouse was an act of agricultural desperation. In the midst of this worried conversation, Catharine Greene introduced the group to Eli Whitney, telling the story of her new tambour frame. Whitney denied any claim of mechanical genius and further admitted that he had never seen cotton or a cotton seed in his life. However, he also sensed opportunity. (Eli Whitney, pp. 19-20)

The above illustrates the excellent point my daughter made when I mentioned the entrepreneurial strength of her husband's unusual ability to gather community around himself and his family. She acknowledged the truth of that, but added, "I've also learned that we don't all have to be entrepreneurs." It seems that Catharine Green, being herself and doing what she did best, was also an essential part of the invention of the cotton gin.

It was her grandfather Riegel who first set in motion Mary Elizabeth’s future career. “He did not approve of our buying cheap penny candy,” Evans said. “He thought it was not good for us . . . so he told us that we could have all the candy we wanted, if we’d make it ourselves.” For Judge Riegel, this dictate was common sense. In the unregulated market of nineteenth-century America, before passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906, store-bought candy was often unhealthy and sometimes deadly. (Mary Elizabeth Evans Sharpe, p. 76)

Modern air-conditioning transformed twentieth-century America no less than Eli Whitney’s cotton gin transformed the nineteenth century. Consumers began to enjoy comfort air not only at the theater, but in restaurants, trains, and stores. By 1957, an Arkansas court concluded that “air conditioning is becoming standard equipment in homes, offices, and public buildings; it contributes to the comfort and efficiency of all those people who have occasion to utilize its benefits and is as necessary as telephones, heating, etc., in courthouses.” The 1970 Federal Census, sometimes called “The Air-Conditioned Census,” showed modern air-conditioning as having circulated people along with air, pushing the American population southward. Today, some 90 percent of American homes have central or room air-conditioning. (Willis Carrier, p. 110)

That so many homes are now air conditioned is still difficult for me to believe. True, we wouldn't have moved to Florida without it, but we never had air conditioning when we lived in the Northeast—not in our homes, not in our cars, and barely even in our workplaces as late as the 1980's. What brought air conditioning to the hospital where I worked was not human comfort, but the fact that the computers we had learned to depend on would not function in the hot weather. Even in 2002, our Boston apartment was not air conditioned, nor was our church. The Arkansas courthouse may have been cool in the 1950's, but at my grandparents' home in Florida, relief came from a relaxed lifestyle and a house designed to take advantage of the Atlantic Ocean breezes.

Buddy [Bolden] died at age fifty-four in 1931, leaving behind no interviews or recordings. Not until two years after his death did jazz historians even begin to recover his name and legacy. In so doing, they realized that what Bolden created between 1900 and 1906 was novel and striking enough to his contemporaries that they believed they were hearing something entirely new. Don Marquis resolved that, if Buddy was not the first to play jazz, “he was the first to popularize it and give the music a base from which to grow.” ...

As tragically as his story ends, Buddy Bolden also serves as a poignant reminder that even marginalized entrepreneurs can flourish where community thrives and where race and class are second to innovation and talent. (Charles "Buddy" Bolden, p. 117)

With the growth of cities came the rise of the department store and the growth of chain stores. Americans living thousands of miles apart were being joined together by magazines, the telephone, Hollywood, the radio, and the automobile. A journalist traveling cross-country in the early twentieth century found Americans from New York to California “are more and more coming to be molded on something of the same outward pattern.” This included their clothing, their homes, and the novels they read. A “mass market” was rising implausibly from a nation that was once a loose collection of regions and not long before at war with itself.

Having mastered mechanization and mass production, industry was suddenly faced with a new crisis. “The problem before us today is not how to produce the goods,” journalist Samuel Strauss (1870–1953) wrote in 1924, “but how to produce the customers.” (Elizabeth Arden, p. 121)

The concept of “style” arose as an important attribute of a product, and style could be manipulated. “This new influence . . . is largely used to make people dissatisfied with what they have of the old order,” advertising executive Earnest Calkins (1868–1964) wrote, “still good and useful and efficient, but lacking the newest touch.” ... Academics disagreed about who was responsible for this phenomenon of consumerism. Some saw its birth as the result of a generation of high-quality, low-cost product being available in the market. Americans had come to expect the newest and best, all at an affordable price. ... Others believed that business was more responsible, more manipulative, having found ways through clever marketing to create new demand.... The journalist Mark Sullivan (1874–1952) believed that new demand was created by businessmen who realized that “if the old could be made to seem passé . . . the new could be sold in profitable quantities.” For Sullivan, consumerism was the result of a calculated push from producers.

Pull or push, consumer or producer, the transformation was real. When Robert and Helen Lynd took a detailed look at attitudes in the town of Muncie, Indiana, in 1929, they found residents being informed by their local paper that the “citizen’s first importance to his country is no longer that of citizen but that of consumer. Consumption is the new necessity.” Consumer credit soared among young people. So did a signature cultural innovation of the age: planned obsolescence. “We are urged deliberately to waste material,” one commentator wrote. “Throw away your razor blades, abandon your motor car, and purchase new.” Style over function, credit, and obsolescence had all become virtues—a way to keep the giant factories of automation humming along, but a complete about-face from the frugal world of the previous century. (Elizabeth Arden, pp. 122-123, emphasis mine)

As with air conditioning, this was not my world, growing up. It's barely my world now. Frugality, making do, wasting nothing, caring for the environment—that was, and is, the the backdrop of our lives. I am not at all happy that Microsoft pulled the plug on Windows 7....

"It is astonishing what you can do when you have a lot of energy, ambition and plenty of ignorance," [Alfred Sloan] concluded. (Alfred Sloan, p. 141)

One GM executive wrote, “The question was no longer ‘can I afford an automobile,’” but—thanks to the marketing brilliance of GM and its leader, “‘can I afford to be without an automobile?’” (Alfred Sloan, p. 152)

While the term sustainability would not become common until the 1970s, the need to balance growth with resource conservation is the fourth important entrepreneurial theme in America. Sustainability would come to address pollution, overconsumption, and climate change, but its roots were set in the conservation movement that sprang up in the early twentieth century. (Stephen Mather, p. 163, emphasis mine)

This was my world. I've never quite been comfortable with what has been called "environmentalism," but "conservationism" was as much a part of my youth as our beloved Adirondack Mountains. Certainly both involve politics, and I can't deny that the environmentalist movement has facilitated much good, but in my gut it feels like anger and violence, whereas conservationism feels like love and respect and good times with friends.

The national park system is an American crucible, facing the irreconcilable mandates of providing a world-class experience to every visitor who enters while leaving the park and its resources unimpaired. The American consumer experience appears to have reached its limit in places like Yellowstone and Yosemite. “These are irreplaceable resources,” says retired park superintendent Joan Anzelmo. “We have to protect them by putting some strategic limits on numbers, or there won’t be anything left.” (Stephen Mather, p. 177)

“The predominant narrative that you hear when somebody puts solar on their rooftop is, ‘If you’ve gone solar and I haven’t, you’re free-riding on the system, and you’re shipping costs to me.’ You hear that here in the US, in Europe, in Australia. It’s a common refrain,” Rochon says, promoted by utility companies. “It’s black and white and very persuasive: You’re not paying utility bills so you are cheating the system.”

Her counternarrative redefines those who adopt solar as responsible stewards of the grid. People who invest in their homes, adding solar panels, air-source heat pumps, and insulation have, Rochon says, “prepaid their electricity bill for the next ten years. When the sun is shining and everybody has turned on their air-conditioning, their house is not part of the problem. We need these people to participate.” They spend private dollars at no risk to others, generate clean local power, support the economy, and create jobs. (Emily Rochon, p. 185)

I wonder where this "predominant narrative" is heard? It's new to me. I only hear praises for those who are investing in alternative energy for their homes. At worst I hear complaints about taxpayer-funded subsidies that they take advantage of.

Fundamental to Rochon’s work in both Europe and the United States is the creation of new entrepreneurial opportunities and attractive business models, and helping to spread best practices. “If you give renewable energy developers in the US the right framework and right incentives, they can solve almost any problem. You don’t see that same level of creativity in Europe,” she says. “It doesn’t have the same capitalist roots. But the story that I tell is that you just need to give the market the right framework and let the forces innovate. Renewable energy developers everywhere can be extraordinarily clever, creative people if you give them the space within which to do that stuff, and the guidance to ensure it happens responsibly.” (Emily Rochon, p. 186)

“Everyone’s got their stuff; they just need to be self-aware, find things that make good use of those skills, and put the right people around them.” (Jason Jacobs, p. 247)

Pitting start-up entrepreneurship against big-company “intrapreneurship” may be the wrong debate, however. Innovation is successful when delivered as part of a compelling business model, and when its sponsoring entrepreneurs have the support of a robust community. These qualities can be found in start-up ecosystems, but they also exist in large, well-run organizations. (Meghan Winegrad, p. 260)

Steve Jobs has observed that “creativity is just connecting things.” This suggests that entrepreneurs with rich life experiences have a distinct advantage. The more time spent listening, observing, reading, experimenting, sharing, and living—the more “things” they ultimately have to connect, and the more opportunity they uncover. ...

Likewise, our stories suggest that each river of entrepreneurial success is fed by an incalculable number of little streams. These streams flow from the talent, resources, wisdom, and luck generated by the community each entrepreneur works to assemble. Our virtual barroom of entrepreneurs, encompassing three centuries and delivering innovations as different as the cotton gin and Hamilton, would undoubtedly endorse this truth: the stronger the community, the greater the chances for success. (A Model for Innovation and Community, p. 273, 284)

This would suggest that extroverts have a decided advantage in the world of entrepreneurship, and it may very well be true. But introverts bring their own collections of "listening, observing, reading, experimenting, sharing, and living" that should not be underestimated.

Moreover, for extroverts and introverts alike, it is an encouraging truth that many important life experiences look very much like failures. I'm not of the school that believes failure, per se, to be a prerequisite for success, but the entrepreneurs in this barroom prove that repeated failures, enormous disadvantages, and even mental illness and early death don't disqualify one from making important contributions to the world.

I have but one complaint about Innovation on Tap: the use of the term, "people of color." I can't wait for this to go the way of other, now-outdated designations that wrongfully categorize people. As if the world consists of but two classes of people: People of Color and ... what? The Colorless? It has already become a meaningless term, with people now being told, "You're not really a Person of Color because you are: rich, successful, Republican, anything that makes you one of Them." I've felt this myself, as a woman—not being "really a woman" because I don't toe someone's party line—and it stinks. Then there was the American schoolteacher on a Kilimanjaro hike, who couldn't believe her guide was "really African" because he was a Roman Catholic (instead of "worshipping spirits") and had never heard of Kwanzaa. (Yes, I said schoolteacher!) I'm done with this nonsense.

Legion: The Many Lives of Stephen Leeds by Brandon Sanderson (Tor Books, 2018), containing

Legion: The Many Lives of Stephen Leeds by Brandon Sanderson (Tor Books, 2018), containing

Legion (2012)

Legion: Skin Deep (2014)

Lies of the Beholder (2018)

My grandson, with some assistance from my brother, has been pushing me to read Brandon Sanderson. I've been intimidated. Me, intimidated by books? I read voraciously, averaging five and a half books each month since I began keeping score in 2010. I read fiction and non-fiction, short books and long books, books for all ages—though not of all genres: you'll find little or no Romance or Horror on my lists, and I loathe Coming of Age novels. But Sanderson doesn't appear to fall into any of the hated genres; why am I intimidated?

It's probably the commitment involved. They want me to read the Mistborn series: six books, running between five and six hundred pages each. Really, I could do it. It's less than two months' worth of reading; the issue is what books would I not be reading in that time? (That's two months' worth of reading for me; my grandsons seem to be able to polish off these books in a day or two.)

So I started small, with The Rithmatist. Fewer pages, and just one book. By the time I was finished, I was anxious to read the sequel, but since that hasn't yet been written, I'm safe for a while. I won't go through the reasons getting Mistborn has eluded me at the library, but its time will come. Instead, the last time I was browsing the library shelves I found Legion. It's actually three books, but all together only 352 pages, so not intimidating at all.

Not intimidating, but gripping. The premise—a man of unparalleled genius whose mind keeps him from descending into madness through the creation of hallucinatory people who contain and control his knowledge—is unique as far as I know. I see an opportunity here for a very interesting TV detective series.

Sanderson calls these his "most personal" stories. I think he would be a fascinating person to know.

An Experiment in Criticism by C. S. Lewis (Cambridge University Press, 1961)

An Experiment in Criticism by C. S. Lewis (Cambridge University Press, 1961)

This book was not written for me; the author himself said so: I am writing about literary practice and experience from within, for I claim to be a literary person myself and I address other literary people. (p. 130)

I am a literate person. I read, and what's more I write, but any of my English teachers could assure you that I've never been a literary person. I've always loved reading books, but loathed analyzing them—at least in the way English teachers require. And most of the examples Lewis discusses here go 'way over my head.

Nonetheless, I found this to be a valuable book, largely because I don't think Lewis could discuss buttered toast without touching on interesting subjects.

The first time I read An Experiment in Criticism (unfathomable years ago), I marked interesting passages with blue highlighting. (That's how I know it was a very long time ago; it has been decades since I gave up desecrating the pages of a book with anything but light pencil.) This time I used my now-traditional sticky notes. They are far fewer, not because the highlighted passages are no longer interesting to me, but because I didn't want to type them up for the review. But I present a few:

The first demand any work of any art makes upon us is surrender. Look. Listen. Receive. Get yourself out of the way. (There is no good asking first whether the work before you deserves such a surrender, for until you have surrendered you cannot possibly find out.) (p. 19)

Without some degree of realism in content—a degree proportional to the reader's intelligence—no deception will occur at all. No one can deceive you unless he makes you think he is telling the truth. The unblushingly romantic has far less power to deceive than the apparently realistic. Admitted fantasy is precisely the kind of literature which never deceives at all. Children are not deceived by fairy-tales; they are often and gravely deceived by school-stories. Adults are not deceived by science-fiction; they can be deceived by the stories in the women's magazines. None of us are deceived by the Odyssey, the Kalevala, Beowulf, or Malory. The real danger lurks in sober-faced novels where all appears to be very probable but all is in fact contrived to put across some social or ethical or religious or anti-religious "comment on life." For some at least of such comments must be false. To be sure, no novel will deceive the best type of reader. He never mistakes art either for life or for philosophy. He can enter, while he reads, into each author's point of view without either accepting or rejecting it, suspending when necessary his disbelief and (which is harder) his belief. (pp. 67-68)

The danger of realistic fiction deserves a post of its own; I believe it has profound implications for our mass-media-drenched society. Let's just say I'm feeling better about female cops who manage to run down bad guys while wearing heels, and computer specialists who can hack into the Pentagon faster than my computer can boot.

We must not be deceived by the contemporary practice of sorting books out according to the "age-groups" for which they are supposed to be appropriate. That work is done by people who are not very curious about the real nature of literature nor very well acquainted with its history. It is a rough rule of thumb for the convenience of schoolteachers, librarians, and the publicity departments in publishers' offices. Even as such it is very fallible. Instances that contradict it (in both directions) occur daily. (p. 71)

When my pupils have talked to me about Tragedy (they have talked much less often uncompelled, about tragedies), I have sometimes discovered a belief that it is valuable, is worth witnessing or reading, chiefly because it communicates something called the tragic "view" or "sense" or "philosophy" of "life." This content is variously described, but in the most widely diffused version it seems to consist of two propositions: (1) That great miseries result from a flaw in the principle sufferer. (2) That these miseries, pushed to the extreme, reveal to us a certain splendour in man, or even in the universe. Though the anguish is great, it is at least not sordid, meaningless, or merely depressing.

No one denies that miseries with such a cause and such a close can occur in real life. But if tragedy is taken as a comment on life in the sense that we are meant to conclude from it "This is the typical or usual, or ultimate, form of human misery," then tragedy becomes wishful moonshine. Flaws in character do cause suffering; but bombs and bayonets, cancer and polio, dictators and roadhogs, fluctuations in the value of money or in employment, and mere meaningless coincidence, cause a great deal more. Tribulation falls on the integrated and well adjusted and prudent as readily as on anyone else. Nor do real miseries often end with a curtain and a roll of drums "in calm of mind, all passion spent." The dying seldom make magnificent last speeches. And we who watch them die do not, I think, behave very like the minor characters in a tragic death-scene. For unfortunately the play is not over. We have no exeunt omnes. The real story does not end: it proceeds to ringing up undertakers, paying bills, getting death certificates, finding and proving a will, answering letters of condolence. There is no grandeur and no finality. Real sorrow ends neither with a bang nor a whimper. Sometimes, after a spiritual journey like Dante’s, down to the centre and then, terrace by terrace, up the mountain of accepted pain, it may rise into peace—but a peace hardly less severe than itself. Sometimes it remains for life, a puddle in the mind which grows always wider, shallower, and more unwholesome. Sometimes it just peters out, as other moods do. One of these alternatives has grandeur, but not tragic grandeur. The other two—ugly, slow, bathetic, unimpressive—would be of no use at all to a dramatist. The tragedian dare not present the totality of suffering as it usually is in its uncouth mixture of agony with littleness, all the indignities and (save for pity) the uninterestingness, of grief. It would ruin his play. It would be merely dull and depressing. He selects from the reality just what his art needs; and what it needs is the exceptional. Conversely, to approach anyone in real sorrow with these ideas about tragic grandeur ... would be worse than imbecile: it would be odious. (pp 77-79)

As I have said, more than once: Romantic tragedy makes great opera, but a lousy life. And the point about the artist extracting only the exceptional from reality because that's what his art needs? C. S. Lewis, prophet of the evening news!

In good reading there ought to be no "problem of belief." I read Lucretius and Dante at a time when (by and large) I agreed with Lucretius. I have read them since I came (by and large) to agree with Dante. I cannot find that this has much altered my experience, or at all altered my evaluation, of either. A true lover of literature should be in one way like an honest examiner, who is prepared to give the highest marks to the telling, felicitous and well-documented exposition of views he dissents from or even abominates. (p. 86)

No poem will give up its secret to a reader who enters it regarding the poet as a potential deceiver, and determined not to be taken in. We must risk being taken in, if we are to get anything. The best safeguard against bad literature is a full experience of good; just as a real and affectionate acquaintance with honest people gives a better protection against rogues than a habitual distrust of everyone. (p. 94, emphasis mine)

At some schools children are taught to write out poetry they have learned for repetition not according to the lines but in "speech-groups." The purpose is to cure them of what is called "sing-song." This seems a very short-sighted policy. If these children are going to be lovers of poetry when they grow up, sing-song will cure itself in due time, and if they are not it doesn't matter. In childhood sing-song is not a defect. It is simply the first form of rhythmical sensibility; crude itself, but a good symptom not a bad one. This metronomic regularity, this sway of the whole body to the metre simply as metre, is the basis which makes possible all later variations and subtleties. For there are no variations except for those who know a norm, and no subtleties for those who have not grasped the obvious. Again, it is possible that those who are now young have met vers libre too early in life. When this is real poetry, its aural effects are of extreme delicacy and demand for their appreciation an ear long trained on metrical poetry. Those who think they can receive vers libre without a metrical training are, I submit, deceiving themselves; trying to run before they can walk. (p. 103)

If we have to choose, it is always better to read Chaucer again than to read a new criticism of him. (p. 124)

To take a man up very sharp, to demand sternly that he shall explain himself, to dodge to and fro with your questions, to pounce on every apparent inconsistency, may be a good way of exposing a false witness or a malingerer. Unfortunately, it is also the way of making sure that if a shy or tongue-tied man has a true and difficult tale to tell you will never learn it. (p. 128, emphasis mine)

None of these quotations gives you a proper feel for the book, which is about good and bad ways of reading, and judging a book by the kind of reading it invites. Lewis's ideas are interesting and often compelling, but what I really wish is that somebody better than I would take these ideas and apply them to recent generations, who have by and large given up reading of any sort in favor of other media.

Ordinary Grace by William Kent Krueger (Atria, 2013)

Ordinary Grace by William Kent Krueger (Atria, 2013)

My son-in-law has had remarkable success in recommending fiction books for me. This was one of his few failures. Despite its New York Times bestseller status, its awards, and the glowing reviews, it's not my kind of book. Yes, it's a mystery, and that is its best quality. I don't hold anything against it just because I figured out whodunit before it was revealed. I rather enjoy feeling clever.

However, it is a coming-of-age story, and that genre sits on the bottom of my rankings, along with Horror and Romance. It's much to the credit of The Silent Swan that I esteem that book so highly, given that it could also be called a coming-of-age story. A line from my review of that book is just as applicable here: If this story provides an accurate description of what goes on in a teenage boy's mind whenever he sees a woman ... let's just say I'm feeling a lot better about burqas. And a lot worse about teenage boys.

But my dislike of the genre is not particularly about sex; it's more the self-centered focus of what's going on in the protagonist's mind and heart. It's not just teenage boys whose thoughts are such cesspools of selfishness, envy, anger, pettiness, greed, and lust. God knows (and I use that phrase in all reverence) I don't need to look any further than my own heart to find all that. But I don't enjoy seeing it all spread out before me as on an autopsy table—and more often than not presented as something normal and therefore nothing to be ashamed of. More to the point, I don't think it's good for me to see it like that.

Plus, having grown up in a family where we never, ever used bad language, and in a time where women did not swear and men did not swear in front of women—and those conventions kept a tight rein on the media—I just can't get used to it. It is physically painful to me to hear such language, and reading it isn't much better. (There are some exceptions.) I do not usually seek out books that hurt.

Ordinary Grace is far from the worst of offenders in either subject or language. In fact, it's quite mild, and somewhat redeemed by the mystery. The only reason I'm bothering with this negative review is to figure out (and help gift-givers to figure out) what works for me in a book, and what does not. Even at my age I'm still a mystery to myself!

In fact, I rather suspect that my book-loving sister-in-law would enjoy Ordinary Grace very much. I think I can find it a good home. (Update: I was right, and I was wrong. I must find another good home, because she has already read Ordinary Grace, and yes, she did enjoy it.)

Reflections on the Psalms by C. S. Lewis (Harcourt Brace & Company, first published 1958)

Reflections on the Psalms by C. S. Lewis (Harcourt Brace & Company, first published 1958)

C. S. Lewis fan though I am, I was not prepared for how much I would enjoy this book. Not only does Lewis have wise advice for understanding and getting the most out of even the problematic psalms, but the book is filled as well with general wisdom.

Lewis's take on the Psalms has inspired me to read through them again before starting over from Genesis. It is very helpful to learn more about the culture in which they were written, and about poetry as well. He deals with not only what they might have meant to the writers of these poems, but also with why it's legitimate to view them as prophecy and with a Christian interpretation. A Christian can hardly insist that the Psalms only mean what the writers means, since Jesus freely interpreted them his own way. Nor does Lewis shy away from the parts that are shockingly offensive, such as the last verse of Psalm 137 ("Happy shall he be who takes your little ones and dashes them against the rock!"), which Don McLean wisely left out of his simple, beautiful, and haunting Babylon.

I think it is important to make a distinction: between the conviction that one is in the right and the conviction that one is “righteous,” is a good man. Since none of us is righteous, the second conviction is always a delusion. But any of us may be, probably all of us at one time or another are, in the right about some particular issue. What is more, the worse man may be in the right against the better man. Their general characters have nothing to do with it. The question whether the disputed pencil belongs to Tommy or Charles is quite distinct from the question which is the nicer little boy, and the parents who allowed the one to influence their decision about the other would be very unfair. (It would be still worse if they said Tommy ought to let Charles have the pencil whether it belonged to him or not, because this would show he had a nice disposition. That may be true, but it is an untimely truth. An exhortation to charity should not come as rider to a refusal of justice. It is likely to give Tommy a lifelong conviction that charity is a sanctimonious dodge for condoning theft and whitewashing favouritism.) We need therefore by no means assume that the Psalmists are deceived or lying when they assert that, as against their particular enemies at some particular moment, they are completely in the right. Their voices while they say so may grate harshly on our ear and suggest to us that they are unamiable people. But that is another matter. And to be wronged does not commonly make people amiable. (pp 17-18)

I made a similar point in A Debt Is a Debt Is a Debt.

It seems that there is a general rule in the moral universe which may be formulated “The higher, the more in danger”. The “average sensual man” who is sometimes unfaithful to his wife, sometimes tipsy, always a little selfish, now and then (within the law) a trifle sharp in his deals, is certainly, by ordinary standards, a “lower” type than the man whose soul is filled with some great Cause, to which he will subordinate his appetites, his fortune, and even his safety. But it is out of the second man that something really fiendish can be made; an Inquisitor, a Member of the Committee of Public Safety. It is great men, potential saints, not little men, who become merciless fanatics. Those who are readiest to die for a cause may easily become those who are readiest to kill for it. (p 28)

If I am never tempted, and cannot even imagine myself being tempted, to gamble, this does not mean that I am better than those who are. The timidity and pessimism which exempt me from that temptation themselves tempt me to draw back from those risks and adventures which every man ought to take. (p 29)

There is a stage in a child’s life at which it cannot separate the religious from the merely festal character of Christmas or Easter. I have been told of a very small and very devout boy who was heard murmuring to himself on Easter morning a poem of his own composition which began “Chocolate eggs and Jesus risen”. This seems to me, for his age, both admirable poetry and admirable piety. But of course the time will soon come when such a child can no longer effortlessly and spontaneously enjoy that unity. He will become able to distinguish the spiritual from the ritual and festal aspect of Easter; chocolate eggs will no longer be sacramental. And once he has distinguished he must put one or the other first. If he puts the spiritual first he can still taste something of Easter in the chocolate eggs; if he puts the eggs first they will soon be no more than any other sweetmeat. They have taken on an independent, and therefore a soon withering, life. (pp 48-49)

I am inclined to think a Christian would be wise to avoid, where he decently can, any meeting with people who are bullies, lascivious, cruel, dishonest, spiteful and so forth. Not because we are “too good” for them. In a sense because we are not good enough. We are not good enough to cope with all the temptations, nor clever enough to cope with all the problems, which an evening spent in such society produces. The temptation is to condone, to connive at; by our words, looks and laughter, to “consent”. The temptation was never greater than now when we are all (and very rightly) so afraid of priggery or “smugness”. And of course, even if we do not seek them out, we shall constantly be in such company whether we wish it or not. This is the real and unavoidable difficulty. We shall hear vile stories told as funny; not merely licentious stories but (to me far more serious and less noticed) stories which the teller could not be telling unless he was betraying someone’s confidence. We shall hear infamous detraction of the absent, often disguised as pity or humour. Things we hold sacred will be mocked. Cruelty will be slyly advocated by the assumption that its only opposite is “sentimentality”. The very presuppositions of any possible good life—all disinterested motives, all heroism, all genuine forgiveness—will be, not explicitly denied (for then the matter could be discussed), but assumed to be phantasmal, idiotic, believed in only by children. What is one to do? For on the one hand, quite certainly, there is a degree of unprotesting participation in such talk which is very bad. We are strengthening the hands of the enemy. We are encouraging him to believe that “those Christians”, once you get them off their guard and round a dinner table, really think and feel exactly as he does. By implication we are denying our Master; behaving as if we “knew not the Man”. On the other hand is one to show that, like Queen Victoria, one is “not amused”? Is one to be contentious, interrupting the flow of conversation at every moment with “I don’t agree, I don’t agree”? Or rise and go away? But by these courses we may also confirm some of their worst suspicions of “those Christians”. We are just the sort of ill-mannered prigs they always said. Silence is a good refuge. People will not notice it nearly so easily as we tend to suppose. And (better still) few of us enjoy it as we might be in danger of enjoying more forcible methods. Disagreement can, I think, sometimes be expressed without the appearance of priggery, if it is done argumentatively not dictatorially; support will often come from some most unlikely member of the party, or from more than one, till we discover that those who were silently dissentient were actually a majority. A discussion of real interest may follow. Of course the right side may be defeated in it. That matters very much less than I used to think. The very man who has argued you down will sometimes be found, years later, to have been influenced by what you said. There comes of course a degree of evil against which a protest will have to be made, however little chance it has of success. There are cheery agreements in cynicism or brutality which one must contract out of unambiguously. If it can’t be done without seeming priggish, then priggish we must seem. For what really matters is not seeming but being a prig. If we sufficiently dislike making the protest, if we are strongly tempted not to, we are unlikely to be priggish in reality. Those who positively enjoy, as they call it, “testifying” are in a different and more dangerous position. As for the mere seeming—well, though it is very bad to be a prig, there are social atmospheres so foul that in them it is almost an alarming symptom if a man has never been called one. Just in the same way, though pedantry is a folly and snobbery a vice, yet there are circles in which only a man indifferent to all accuracy will escape being called a pedant, and others where manners are so coarse, flashy and shameless that a man (whatever his social position) of any natural good taste will be called a snob. What makes this contact with wicked people so difficult is that to handle the situation successfully requires not merely good intentions, even with humility and courage thrown in; it may call for social and even intellectual talents which God has not given us. It is therefore not self-righteousness but mere prudence to avoid it when we can. (pp 71-74) [emphasis mine]

Of course this appreciation of, almost this sympathy with, creatures useless or hurtful or wholly irrelevant to man, is not our modern “kindness to animals”. That is a virtue most easily practised by those who have never, tired and hungry, had to work with animals for a bare living, and who inhabit a country where all dangerous wild beasts have been exterminated. The Jewish feeling, however, is vivid, fresh, and impartial. In Norse stories a pestilent creature such as a dragon tends to be conceived as the enemy not only of men but of gods. In classical stories, more disquietingly, it tends to be sent by a god for the destruction of men whom he has a grudge against. The Psalmist’s clear objective view—noting the lions and whales side by side with men and men’s cattle—is unusual. And I think it is certainly reached through the idea of God as Creator and sustainer of all. (pp 84-85)

The next several quotations are from the very helpful chapter entitled simply "Scripture."

The human qualities of the raw materials [of Scripture] show through. Naïvety, error, contradiction, even (as in the cursing Psalms) wickedness are not removed. The total result is not “the Word of God” in the sense that every passage, in itself, gives impeccable science or history. It carries the Word of God; and we (under grace, with attention to tradition and to interpreters wiser than ourselves, and with the use of such intelligence and learning as we may have) receive that word from it not by using it as an encyclopedia or an encyclical but by steeping ourselves in its tone or temper and so learning its overall message. (pp 109-110)

We might have expected, we may think we should have preferred, an unrefracted light giving us ultimate truth in systematic form—something we could have tabulated and memorised and relied on like the multiplication table. One can respect, and at moments envy, both the Fundamentalist’s view of the Bible and the Roman Catholic’s view of the Church. (p 112)

We may observe that the teaching of Our Lord Himself, in which there is no imperfection, is not given us in that cut-and-dried, fool-proof, systematic fashion we might have expected or desired. He wrote no book. We have only reported sayings, most of them uttered in answer to questions, shaped in some degree by their context. And when we have collected them all we cannot reduce them to a system. He preaches but He does not lecture. He uses paradox, proverb, exaggeration, parable, irony; even (I mean no irreverence) the “wisecrack”. He utters maxims which, like popular proverbs, if rigorously taken, may seem to contradict one another. His teaching therefore cannot be grasped by the intellect alone, cannot be “got up” as if it were a “subject”. If we try to do that with it, we shall find Him the most elusive of teachers. He hardly ever gave a straight answer to a straight question. He will not be, in the way we want, “pinned down”. The attempt is (again, I mean no irreverence) like trying to bottle a sunbeam. (pp 112-113)

Descending lower, we find a somewhat similar difficulty with St. Paul. I cannot be the only reader who has wondered why God, having given him so many gifts, withheld from him (what would to us seem so necessary for the first Christian theologian) that of lucidity and orderly exposition. (p 113)

It may be that what we should have liked would have been fatal to us if granted. It may be indispensable that Our Lord’s teaching, by that elusiveness ... should demand a response from the whole man, should make it so clear that there is no question of learning a subject but of steeping ourselves in a Personality, acquiring a new outlook and temper, breathing a new atmosphere, suffering Him, in His own way, to rebuild in us the defaced image of Himself. So in St. Paul. Perhaps the sort of works I should wish him to have written would have been useless. The crabbedness, the appearance of inconsequence and even of sophistry, the turbulent mixture of petty detail, personal complaint, practical advice, and lyrical rapture, finally let through what matters more than ideas ... Christ Himself operating in a man’s life. And in the same way, the value of the Old Testament may be dependent on what seems its imperfection. It may repel one use in order that we may be forced to use it in another way—to find the Word in it, not without repeated and leisurely reading nor withoutdiscriminations made by our conscience and our critical faculties, to re-live, while we read, the whole Jewish experience of God’s gradual and graded self-revelation, to feel the very contentions between the Word and the human material through which it works. For here again, it is our total response that has to be elicited. (pp 113-114)

Yet it is, perhaps, idle to speak here of spirit and letter. There is almost no “letter” in the words of Jesus. Taken by a literalist, He will always prove the most elusive of teachers. Systems cannot keep up with that darting illumination. No net less wide than a man’s whole heart, nor less fine of mesh than love, will hold the sacred Fish. (p 119)

Between different ages there is no impartial judge on earth, for no one stands outside the historical process; and of course no one is so completely enslaved to it as those who take our own age to be, not one more period, but a final and permanent platform from which we can see all other ages objectively. (p 121)

Till We Have Faces: A Myth Retold by C. S. Lewis (Harcourt Brace, 1956)

Till We Have Faces: A Myth Retold by C. S. Lewis (Harcourt Brace, 1956)

Of his re-telling of the Cupid and Psyche myth, C. S. Lewis said, "That book, which I consider far and away the best I have written, has been my one big failure both with the critics and with the public." The first time I read Till We Have Faces, I will admit, my sympathies were with those who did not appreciate it.

My ignorance of mythological history was a problem of course. Cupid I knew, but that was about it; how much less could I have told anything about their story as written in Apuleius's Metamorphoses, which was Lewis's inspiration. More than that, however, this novel is written in a different style from Lewis's other works; it is much like George MacDonald's Phantastes and Lilith. Lewis considered those two books among MacDonalds's best writing. I did not care much for either on first reading, but I love them now.

What he does best is fantasy—fantasy that hovers between the allegorical and the mythopoeic. And this, in my opinion, he does better than any man. (From the preface to Lewis's George MacDonald: An Anthology.)

Till We Have Faces is just such a book, and Lewis crafted it very, very well. It's no wonder he was pleased with his efforts. My second reading found me loving it for what it is, instead of being frustrated that it is not at all like Lewis's other fiction. That this is not a genre everyone likes is evident from its initial reception, though Walter Hooper, in his mammoth compendium, C. S. Lewis: A Companion and Guide, reports that later years have been kinder.

The main charge against the novel when it first appeared was obscurity. "What is he trying to say?" However, in recent years there has been a serious re-assessment of the book, almost an about-face in criticism, and it is generally regarded, not only as Lewis's best book, but as a very great book.

I found Hooper's analysis to be helpful in understanding both the Cupid and Psyche myth and what Lewis made of it in Till We Have Faces. It's also useful to have read the Biblical Book of Job. However, I think I would have enjoyed it nearly as much this time around simply because of having been schooled in the style by George MacDonald. Some people—our daughter for one—were blessed to love the book on first reading, but if you aren't, you may find it worthwhile to give it a second chance.

The Story of Christianity, Volume 2: The Reformation to the Present Day by Justo L. Gonzalez (HarperOne, 2010)

The Story of Christianity, Volume 2: The Reformation to the Present Day by Justo L. Gonzalez (HarperOne, 2010)

The second half of my Church History class, naturally, is using the second book in Gonzalez's series. Gonzalez is a liberal Cuban Methodist who favors Liberation Theology, and as I suspected from the end of the first volume (my review is here), his biases are frustratingly clear. That's okay though—it's an unavoidable failing of those who write books, especially history books—but it means I especially appreciate the class format that allows for questions, explanations, clarifications, and corrections by someone I trust. I take the fact that these books are recommended by someone whose biases must be radically different (Keith Mathison on the Ligonier Ministries site) as confirmation of Fr. Trey's opinion that these are among the best available, and most accessible, for the topic. I'm sure I could get a different perspective from the author who has Mathison's top recommendation, but Nick Needham's 2000 Years of Christ’s Power is four huge volumes and growing (at $20 each for Kindle), and I'm not sure I know I couldn't stomach that much of a Reformed Theology bias at the moment, so let's be realistic. I'll stick with Gonzalez and trust Fr. Trey to provide the necessary balance.

The trouble comes when the book tackles material that I actually know something about. It reminds me of my problem with media coverage: There have been many times in my life when I've seen reported (in mainstream, reputable media) stories of which I have known directly the intimate details, and every one of them has contained significant errors. Why I continue to believe news stories of which I otherwise know nothing is both amazing and shaming to me. Out of charity (and, to be honest, laziness/busy-ness) I won't say that what Gonzalez says is out-and-out wrong, but I will say that his words do not seem to be those of a historian who understands the times and the people of Colonial America, neither of the time and place in which I grew up. It makes me wonder about the accuracy of the other parts of his books.

Take just for one small example Gonzalez's statement, "At first, colonials were not even allowed to own land." The implication is that this is something unusual and shocking, as if those who came over had all been landowners back home. Plus, anyone who has done even minor genealogical research in early New England finds maps indicating the allocation of property among various families. Possibly this was not "ownership" as we understand it today, but very soon in history the people were subdividing, selling, trading, and willing it to their children—which sounds a lot like ownership to me. It's clear that Gonzalez has a particular story to tell, and is picking and choosing his facts accordingly.

Here are a few other random things that struck me, some important, some trivial. Italics indicates quotations from the book.

- Gonzalez's take on Salem in 1692 seems bizarre, and I'm not happy with the mocking tone in which he discusses people who believe that witches might be real. I speak as one whose innocent ancestors really suffered on the wrong end of the New England witch hunt—but who also believes that modern-day America takes the idea of witchcraft much too lightly.

- I know one must condense and condense to cover so many years in two volumes, but how on earth can you talk about Jonathan Edwards without mentioning "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God"?

- By the 1950s, television had become a common household feature in most of the industrialized world. Really? My family, solidly middle class North Americans living in a prosperous New York town, did not own a television set until 1959. Gonzalez was born in Cuba, and stayed there at least long enough to graduate from seminary, so perhaps that's what life in the United States looked like to him as a child. But it does not square with what I know of the times.

- The very idea of liberalism implied freedom to think as one saw fit—as long as one did not fall into what liberals called superstition. I won't go into the shifting definitions of "liberal" and "conservative" that Gonzalez uses; it's complex, because the definitions have been as fluid in real life as they are in the book. But this statement struck me because it is my complaint about many who call themselves Liberals today: They insist that you can believe, say, and do anything you want—but that's only true as long as it conforms to their own standards.

- For [John Wesley], as for most of the church through the centuries, the center of worship was communion. This he took and expected his followers to take as frequently as possible, in the official services of the Church of England. Would any modern Methodist recognize this stance?

- Western Christians—particularly Protestants—may have underestimated the power of liturgy and tradition, that allowed [Orthodox] churches to continue their life, and even to flourish, in the most adverse of circumstances.

- Hegel demolishes mathematics: "What is rational exists, and what exists is rational." Take that, pi and the square root of 2!

- Gonzalez insists on framing everything in terms of white vs. non-white slavery and racism; at first it's annoying, then it's almost funny to see how far he can stretch it.

- He labels as "Fundamentalist" nearly everyone and everything not in line with liberal theology, especially anyone in the much-broader category known as Evangelical. Both Fundamentalists and Evangelicals should be insulted. :)

- Some ... even declared that Christians ought to be thankful for Adolf Hitler because he was halting the advance of socialism in Europe. Huh? What part of "National Socialism" don't they (or Gonzalez?) understand?

- Gonzalez manages to distort his coverage of the Vietnam War to imply that Richard Nixon was responsible for the Gulf of Tonkin misinformation, instead of Lyndon Johnson. He doesn't say that directly, but since Nixon is the only president mentioned in connection with the war, what other impression would a casual reader, ignorant of history, receive?

- Cool story from China that I didn't know: While many Chinese Christians capitulated before pressure and persecution, many did not. In some major cities where churches were closed and worship gatherings were prohibited, believers would make it a point to walk in front of the church at the times formerly appointed for worship, nod at one another, and keep on walking.

- How can you write a book about the Church in the 20th and 21st centuries and leave out important factors like these?

- Denominations such as the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) and others that formed in reaction to what they viewed as heresy on the part of the "mainline" Presbyterian churches

- The various Anglican churches formed in reaction to the same problem in the American Episcopal Church. I especially expected Gonzalez to mention this in his section on how the center of gravity of Christianity is shifting from the Northern Hemisphere to the Southern, since many of the new Anglican churches are under the leadership of bishops in Africa. But he doesn't.

- Abortion. One of the biggest issues dividing the modern Church, and the sole mention is in this statement: Under [Pope John Paul II's] leadership, Roman Catholicism throughout the world reaffirmed its condemnation of abortion, at a time when several traditionally Catholic nations were legalizing it—as if the massive opposition to abortion among Protestants didn't even exist.

- Widespread campus Christian movements such as Campus Crusade for Christ (now Cru), Intervarsity Christian Fellowship (IVCF), and Asian Christian Fellowship; Wycliffe Bible Translators; international aid organizations such as World Vision, Compassion, and the International Justice Mission; and the many other Christian groups (the Gideons, Youth With A Mission, the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, Prison Fellowship—to name just a few) that do the work of the Church across denominational boundaries. A history of modern Christianity without them makes no sense.

- Gonzalez keeps talking about cultural and theological creativity, and that makes me nervous. Creativity is great in certain problem-solving situations, such as figuring out how best to express an idea in terms someone from a different cultural background can understand. But in theology? No thanks. It is the standard Bible translation task: fit the words to the truth, not the truth to the words.

That last point sums up the overall impression I have gained from these two books. For all the flaws of the pre-modern Church, its institutions, and its leaders, they were seeking to determine the truth about God and mankind's relationship with Him—to fit society to the truth. But as we neared modern times—perhaps around the time of the French Revolution, certainly by the 19th century—that changed, and efforts shifted to defining truth to fit society. The result? To my mind, a dust-and-ashes faith, with churches barely discernible from social clubs or secular service organizations. Chaotic and ugly philosophies that remind me of the chaos and ugliness that pass for "serious" art and music in our time. A faith hardly worth living for, unrecognizable by the martyrs who thought theirs worth dying for.

The Story of Christianity is a good introduction to church history, as long as one is aware that it is in large measure the truth, but it is not the whole truth, nor is it nothing but the truth. That accepted, I can recommend it highly. The last chapters were certainly depressing, but Gonzalez has hope for the future, and so do I—though perhaps not for the same reasons. Even though the Church abandons God with distressing frequency, God will never abandon His Church. There are always pockets of beauty in the ashes.

There's a passage in the book God's Smuggler where Brother Andrew, who smuggled Bibles into Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union during the Cold War, describes his astonishment at the revival that took place in an old, dead, state-sponsored church in Bulgaria during one of his visits. Night after night the priest encouraged Andrew to preach the clearest, most vibrant Gospel-centered sermons anyone could want. They carried on that way for many days before the government finally stopped them—the priest had been such a reliable puppet they couldn't believe he didn't have some "good" motive for what he was doing. Andrew learned through that experience never to call a church dead. It is God's church, called by his name, and at any moment his Spirit may blow through and ignite fires of faith that will never be extinguished.

Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray by Sabine Hossenfelder (Basic Books, 2018)

Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray by Sabine Hossenfelder (Basic Books, 2018)

This is my son-in-law's book, which I started perusing during our recent visit, to see if I might be interested. I found it both more interesting and slower to read than I had expected, so I'm borrowing it.

Sabine Hossenfelder, a German theoretical physicist, is worried about the state of her field. I'm not even going to try to summarize the book, which is an entertaining, if worrisome and frequently confusing, series of interviews with her colleagues. Let's just say that it is getting more and more difficult to test theories in particle physics by the time-honored means of experimentation in the real world; CERN's Large Hadron Collider has not provided the results many people were expecting and indeed counting on; and physicists are beginning to sound more like philosophers than scientists.

I can't believe what this once-venerable profession has become. Theoretical physicists used to explain what was observed. Now they try to explain why they can't explain what was not observed. And they're not even good at that. (p 108)

In case I left you with the impression that [physicists] understand the theories we work with, I am sorry, we don't. (p 193)

Physics professor and popular science author Chad Orzel* explains to her,

"As I understand it, there's a divide between the epistemological and the ontological camps. In the ontological camp the wave function is a real thing that exists and changes, and in the epistemological camp the wave function really just describes what we know—it's just quantifying our ignorance about the world. And you can put everybody on a continuum between these two interpretations." (p 135)

That sounds more like theologians than scientists.

Interviewed by the author, cosmologist and mathematician George Ellis looks at the big picture and doesn't like what he sees.

"There are physicists now saying we don't have to test their ideas because they are such good ideas ... They're saying—explicitly or implicitly—that they want to weaken the requirement that theories have to be tested. ... To my mind that's a step backwards by a thousand years. ... Science is having a difficult time out there, with all the talk about vaccination, climate change, GMO crops, nuclear energy, and all of that demonstrating skepticism about science. Theoretical physics is supposed to be the bedrock, the hardest rock, of the sciences, showing how it can be completely trusted. And if we start loosening the requirements over here, I think the implications are very serious for the others." (p 213)

Ellis continues:

"[A lot] of the reasons people are rejecting science is that scientists like Stephen Hawking and Lawrence Krauss and others say that science proves God doesn't exist, and so on—which science cannot prove, but it results in a hostility against science, particularly in the United States. If you're in the Middle West USA, and your whole life and your community is built around the church, and a scientist comes along and says 'Get rid of this,' then they better have a very solidly based argument for what they say. But David Hume already said 250 years ago that science cannot either prove or disprove the existence of God. He was a very careful philosopher, and nothing has changed since then in this regard. These scientists are sloppy philosophers." (p 214)

What's wrong with physics research today? Here are a few problems: universities no longer provide an atmosphere conducive to creative thinking; research decisions—and possibly results—are driven by funding; and peer pressure is a major unholy influence.

Division of labor hasn't yet arrived in academia. While scientists specialize in research topics, they are expected to be all-rounders in terms of tasks: they have to teach, mentor, head labs, lead groups, sit on countless committees, speak at conferences, organize conferences, and—most important—bring in grants to keep the wheels turning. And all the while doing research and producing papers. (p 155)

The fraction of academics holding tenured faculty positions is on the decline, while an increasing percentage of researchers are employed on non-tenured and part-time contracts. From 1974 to 2014 the fraction of full-time tenured faculty in the United States decreased from 29 percent to 21.5 percent. At the same time, the share of part-time faculty increased from 24 percent to more than 40 percent. Surveys by the American Association of University Professors reveal that the lack of continuous support discourages long-term commitment and risk-taking when choosing research topics. (p 155)

Another consequence of the attempt to measure research impact is that it washes out national, regional, and institutional differences because measures for scientific success are largely the same everywhere. This means that academics all over the globe now march to the same drum. (p 156)

You have to get over the idea that all science can be done by postdocs on two-year fellowships. Tenure was institutionalized for a reason, and that reason is still valid. If that means fewer people, then so be it. You can either produce loads of papers that nobody will care about ten years from now, or you can be the seed of ideas that will still be talked about in a thousand years. Take your pick. Short-term funding means short-term thinking. (p 247)

It's well known that such short-term thinking has already been disastrous for American businesses, as the leaders of corporations focus their efforts on the next quarter's results at the expense of long-term success and the health of the company. Politicians focus on winning the next election instead of building relationships and working together to serve the needs of the country. It's hardly surprising that academic research is suffering a similar problem.

In 2010, [theoretical physicist Garret Lisi] wrote an article for Scientific American about his E8 theory. He calls it "an interesting experience" and remembers: "When it came out that the article would appear, Jaques Distler, this string theorist, got a bunch of people together, saying that they would boycott SciAm if they published my article. The editors considered this threat, and asked them to point out what in the article was incorrect. There is nothing incorrect in it. I spent a lot of time on it—there was absolutely nothing incorrect in it. Still, they held on to their threat. In the end, Scientific American decided to publish my article anyway. As far as I know, there weren't any repercussions." (p 166)

Science is sometimes called the "marketplace of ideas," but it differs from a market economy most importantly in the customers we cater to. In science, experts only cater to other experts and we judge each other's products. The final call is based on our success at explaining observation. But absent observational tests, the most important property a theory must have is to find approval by our peers.

For us theoreticians, peer approval more often than not decides whether our theories will ever be put to a test. Leaving aside a lucky few showered with prize money, in modern academia the fate of an idea depends on anonymous reviewers picked from among our colleagues. Without their approval, research funding is hard to come by. An unpopular theory whose development requires a greater commitment of time than a financially unsupported researcher can afford is likely to die quickly. (pp 195-196, emphasis mine)

You'd think that scientists, with the professional task of being objective, would protect their creative freedom and rebel against the need to please colleagues in order to secure continued funding. They don't. (p 197)

You're used to asking about conflicts of interest due to funding from industry. But you should also ask about conflicts of interest due to short-term grants or employment. Does the scientists' future funding depend on producing the results they just told you about? Likewise, you should ask if the scientists' chance of continuing their research depends on their work being popular among their colleagues. ... And finally ... you should also ask whether the scientists have taken steps to address their cognitive biases. Have they provided a balanced account of pros and cons or have they just advertised their own research? (p 248)

If you believe smart people work best when freely following their interests, then you should make sure they can freely follow their interests. (p 197)

That last quote is hardly limited in its application to academia. Teachers, writers, musicians, mothers ... anyone in a creative field knows the frustration of being required by their jobs to do unrelated work that hinders the creative process. We need to recognize that and free them to do what they do best...

...but maybe not completely. Sometimes the interruptions that keep us from our "proper work" can be the key that pushes our work forward. We all want unlimited time to be immersed in our own narrow interests, but that may not be for the best. Still, I think we can all agree that researchers and missionaries are spending too much time fundraising, teachers are spending too much time on cafeteria duty, and church musicians are spending too much time in meetings.

How patently absurd it must appear to someone who last had contact with physics in eleventh grade that people get paid for ideas like that. But then, I think, people also get paid for throwing balls through hoops. (p 192)

Finally, this quote about the problems of peer pressure and insular communities has much broader implications and needs to be emphasized:

Research shows we consider a statement more likely to be true the more often we hear of it. It's called "attention bias" or "mere exposure effect." ... This is the case even if a statement is repeated by the same person. (p 157)

Oh, one more thing: What does beauty, the subject of the subtitle, have to do with all this, since I've left out all references to it? Just that, absent sufficient experimental data, theories are being promoted for their aesthetic properties. Hossenfelder has nothing against aesthetics, but fears that physics is losing its grounding in physical reality in favor of philosophical speculations.

*A few of my readers will be interested to know that Professor Orzel lives in Niskayuna, New York—the town in which I was born, and where Porter lived for much of his life. He teaches at Union College, the school from which my father received his master's degree in physics, albeit long before Orzel was born.

Studies in Words by C. S. Lewis (Second Edition, Cambridge University Press, first published 1960)

Studies in Words by C. S. Lewis (Second Edition, Cambridge University Press, first published 1960)

As I said previously, this is not a book aimed at the hoi polloi—those of us without a strong background in classical literature, Latin, Greek, French, and whatever else scholars were supposed to know in Lewis's day. It is a scholarly, not a popular book. I don't pretend I understood half of what he says, although I could have done better if I'd been more patient. No matter. I still learned a lot. I knew that ignorance of history causes us to misunderstand and falsely judge those who have gone before us; I know now that ignorance of the history of language does the same for the written word. Writing freezes an author's words at a moment in time, while the meaning of those words continues to evolve. Without knowing what a word meant to the author, we may get an entirely false picture of what he is saying.

So what should we do? I think, for ordinary readers, the best we can manage is to be aware that there might be a significant difference between what the author meant and what we think he has said. Simple awareness of the problem should give us the humilty to know that we might not know. And if the word, or phrase, or idea is something we think significant, we—unlike Lewis's original audience—have Google to assist us with a little philological research.

Here are just a few quotes, which ought to be clear enough despite lack of context. Bolded emphasis is mine.

Where the duller reader simply does not understand [a strange phrase], [the highly intelligent and sensitive reader] misunderstands—triumphantly, brilliantly. But it is not enough to make sense. We want to find the sense the author intended. "Brilliant" explanations of a passage often show that a clever, insufficiently informed man has found one more mare’s nest. The wise reader, far from boasting an ingenuity which will find sense in what looks like nonsense, will not accept even the most slightly strained meaning until he is quite sure that the history of the word does not permit something far simpler. (p. 3)

All my life the epithet bourgeois has been, in many contexts, a term of contempt, but not for the same reason. When I was a boy—a bourgeois boy—it was applied to my social class by the class above it; bourgeois meant "not aristocratic, therefore vulgar." When I was in my twenties this changed. My class was now vilified by the class below it; bourgeois began to mean "not proletarian, therefore parasitic, reactionary." Thus it has always been a reproach to assign a man to that class which has provided the world with nearly all its divines, poets, philosophers, scientists, musicians, painters, doctors, architects, and administrators. (p. 21)

When we deplore the human interferences, then the nature which they have altered is of course the unspoiled, the uncorrupted; when we approve them, it is the raw, the unimproved, the savage. (p. 46)

We have learned also from Aristotle, that we must "study what is natural from specimens which are in their natural condition, not from damaged ones." (p. 56)

It's interesting how often we don't follow Aristotle's advice, how often we try to improve situations by concentrating on that which is broken, instead of studying what is working right—from medicine to education, from business to family life.

Unless followed by the word "education," liberal has now lost this meaning [seeking knowledge for its own sake]. For that loss, so damaging to the whole of our cultural outlook, we must thank those who made it the name, first of a political, and then of a theological, party. The same irresponsible rapacity, the desire to appropriate a word for its "selling-power," has often done linguistic mischief. It is not easy now to say at all in English what the word conservative would have said if it had not been "cornered" by politicians. Evangelical, intellectual, rationalist, and temperance have been destroyed in the same way. Sometimes the arrogation is so outrageous that it fails; the Quakers have not killed the word friends. (p. 131)

That English and Protestant authors ... should depend for a scriptural phrase either on Vulgate or Rheims will seem strange to many. Very ill-grounded ideas about the exclusive importance of the Authorized Version in the English biblical tradition are still widely held. (p. 144)

Communis (open, unbarred, to be shared) can mean friendly, affable, sympathetic. Hence communis sensus is the quality of the "good mixer," courtesy, clubbableness, even fellow-feeling. Quintilian says it is better to send a boy to school than to have a private tutor for him at home; for if he is kept away from the herd (congressus) how will he ever learn that sensus which we call Communis? (p. 146)

Innocent, simple, silly, ingenuous ... all illustrate the same thing—the remarkable tendency of adjectives which originally imputed great goodness, to become terms of disparagement. Give a good quality a name and that name will soon be the name of a defect. Pious and respectable are among the comparatively modern casualties, and sanctimonious was once a term of praise. (p. 173)

One of the first things we have to say to a beginner who has brought us his [manuscript] is, "Avoid all epithets which are merely emotional. It is no use telling us that something was 'mysterious' or 'loathsome' or 'awe-inspiring' or 'voluptuous.' Do you think your readers will believe you just because you say so? You must go quite a different way to work. By direct description, by metaphor and simile, by secretly evoking powerful associations, by offering the right stimuli to our nerves (in the right degree and the right order), and by the very beat and vowel-melody and length and brevity of your sentences, you must bring it about that we, we readers, not you, exclaim 'how mysterious!' or 'loathsome' or whatever it is. Let me taste for myself, and you’ll have no need to tell me how I should react to the flavour." (pp 317-318)

And I thought the insistence on "show, don't tell" among current authors was a recent phenomenon. But C. S. Lewis agreed.

The "swear-words"—damn for complaint and damn you for abuse—are a good example. Historically the whole Christian eschatology lies behind them. If no one had ever consigned his enemy to the eternal fires and believed that there were eternal fires to receive him, these ejaculations would never have existed. But inflation, the spontaneous hyperboles of ill temper, and the decay of religion, have long since emptied them of that lurid content. Those who have no belief in damnation—and some who have—now damn inanimate objects which would on any view be ineligible for it. The word is no longer an imprecation. It is hardly, in the full sense, a word at all when so used. Its popularity probably owes as much to its resounding phonetic virtues as to any, even fanciful, association with hell. It has ceased to be profane. It has also become very much less forceful. (pp. 321-322)