I reviewed Tony Hillerman's Leaphorn and Chee detective novels after reading just three of them. This week I completed the 18-book series. (There are additional books written by the author's daughter, Anne Hillerman, after his death, which I may someday check out. But I've never yet been pleased by additions made to a well-loved series, so I'm in no hurry.) The original series comprises:

- The Blessing Way

- Dance Hall of the Dead

- Listening Woman

- People of Darkness

- The Dark Wind

- The Ghostway

- Skinwalkers

- A Thief of Time

- Talking God

- Coyote Waits

- Sacred Clowns

- The Fallen Man

- The First Eagle

- Hunting Badger

- The Wailing Wind

- The Sinister Pig

- Skeleton Man

- The Shape Shifter

I stand by what I said in my original review. The books are thoroughly enjoyable, excellent mysteries, and a beautiful portrait of the American Southwest and Native American culture and religion, primarily Navajo. Hillerman's own views and prejudices occasionally come through a little harshly, but as with the equally rare bad language, that does not diminish the stories.

Having begun the series in the middle, I did not read the books in chronological order, but as I was able to find them. Our library has some, others were available as e-books via Hoopla, and a few I resorted to buying used at a substantial discount. If possible, however, it would be best to read the stories in order. It doesn't matter a bit for the individual mysteries, but helps for following the twists and turns in the lives of the main characters.

If I were a homeschooling mom again, and if my children enjoyed mysteries, and if we were studying the American Southwest, the Leaphorn and Chee books would be on my list of recommended reading. Ditto even if you're not homeschooling.

Discipline Equals Freedom: Field Manual by Jocko Willink (St. Martin's Press, 2017)

Discipline Equals Freedom: Field Manual by Jocko Willink (St. Martin's Press, 2017)

I watched an interview with Jocko Willink and was impressed enough to get this book from the library. It was, however, not at all what I expected. The title led me to hope that the content would be along the lines of my post, Obedience: the Surprising Secret to a Free-Range Childhood, though directed more towards adults, perhaps with tips and examples and encouragement for developing more discipline in our lives. There's a little of that at the beginning, but most of the book is about physical training—and intense physical training at that. I guess that's what I should have expected from a Navy SEAL. If I'm going to get into a physical training routine, I suspect healthymoving.com would be more my speed.

Discipline Equals Freedom is also quite short: 199 pages should be enough to cover a lot of content, but the print is very large and there are not many words on each page. It's more a series of short exhortations, almost a devotional in form.

So—not my kind of book. Nonetheless, I marked a few quotes.

As long as you keep fighting—you win.

Only surrender is defeat.

Only quitting is the end.

Because The Darkness only wins if you let it.

Do not let the Darkness win.

Fight.

Fight on.

To fight against The Darkness is to win.

Fight on.

(p. 77)

Perhaps the most critical form of self-defense is the mind. By being smart and aware, you can avoid situations that are likely to expose you to danger. That being said, there are times when your mind and your intelligence can no longer help you. That is the reality. In those cases, the ultimate form of self-defense is obviously the firearm. It is an equalizer without parallel and is simply unmatched in its ability to eliminate an attacker regardless of size and strength. If a person truly needs self-protection ... there is no substitute for the firearm. (pp. 118-119)

Without proper training, possessing a firearm is useless, or even more dangerous to its owner than not having one. Learning how to shoot quickly and accurately while under stress is absolutely mandatory if one is going to own a firearm. This means finding a good instructor at a quality range to participate in firearms training. (p. 120)

(Contrary to what I chose to quote, self-defense is only a small part of the book, and even in that he deals much more with martial arts than with guns.)

Nineteen Eighty-Four: A Novel by George Orwell (1949)

Nineteen Eighty-Four: A Novel by George Orwell (1949)

A friend of mine recently observed, "I re-read 1984 a few weeks ago. The first time I read it in high school, I thought it was good science fiction. Now it reads like a documentary."

So I decided re-read it myself. In high school I read both Nineteen Eighty-Four and Brave New World, and about all I remember is how much I disliked them both. I am a purist for science fiction. By that I mean not fantasy, and not merely stories set in the future, but stories in which plausible future science plays a more important role than social commentary—think Isaac Asimov and early Robert Heinlein. Thus I wouldn't have called either of the above books science fiction. I personally wouldn't call them good, either. But I thought it was worth another try.

I stand by my original assessment of Nineteen Eighty-Four, though I will acknowledge that Orwell was remarkably prescient in many areas. I know what my friend meant when he said it sounds like a documentary. Just as interesting were the places he got wrong. For example, he completely missed the sexual revolution of the 1960's. He also missed computers, the Internet, social media, and the Information Age—but television served his purposes well enough for "Big Brother is Watching You."

Curiously, I found that most of the analyses I read online consider the climax of the book to be where Winston Smith and Julia betray each other. It seems clear to me, however, that the true climax occurs much earlier in the book, when they believe they are joining the Brotherhood, an organization dedicated to opposing the ruling Party.

"In general terms, what are you prepared to do?"

"Anything that we are capable of," said Winston.

O'Brien had turned himself a little in his chair so that he was facing Winston. He almost ignored Julia, seeming to take it for granted that Winston could speak for her. For a moment the lids flitted down over his eyes. He began asking his questions in a low, expressionless voice, as though this were a routine, a sort of catechism, most of whose answers were known to him already.

"You are prepared to give your lives?"

"Yes."

"You are prepared to commit murder?"

"Yes."

"To commit acts of sabotage which may cause the death of hundreds of innocent people?"

"Yes."

"To betray your country to foreign powers?"

"Yes."

"You are prepared to cheat, to forge, to blackmail, to corrupt the minds of children, to distribute habit-forming drugs, to encourage prostitution, to disseminate venereal diseases—to do anything which is likely to cause demoralization and weaken the power of the Party?"

"Yes."

"If, for example, it would somehow serve our interests to throw sulphuric acid in a child's face—are you prepared to do that?"

"Yes."

At that point any hope for the future is lost, those opposing evil having shown themselves to be no better than their opponents. Everything after that is dénouement.

Here are a few more quotes I found interesting.

Nearly all children nowadays were horrible. What was worst of all was that by means of such organizations as the Spies they were systematically turned into ungovernable little savages, and yet this produced in them no tendency whatever to rebel against the dsicipline of the Party. ... It was almost normal for people over thirty to be frightened of their own children. And with good reason, for hardly a week passed in which "The Times" did not carry a paragraph describing how some eavesdropping little sneak—"child hero" was the phrase generally used—had overheard some compromising remark and denounced its parents to the Thought Police.

If the Party could thrust its hand into the past and say of this or that event, IT NEVER HAPPENED—that, surely, was more terrifying than mere torture and death?

As soon as all the corrections which happened to be necessary in any particular number of "The Times" had been assembled and collated, that number would be reprinted, the original copy destroyed, and the corrected copy placed on the files in its stead. ... Day by day and almost minute by minute the past was brought up to date. ... All history was a palimpsest, scraped clean and reinscribed exactly as often as was necessary.

There was a whole chain of separate departments dealing with proletarian literature, music, drama, and entertainment generally. Here were produced rubishy newspapers containing almost nothing except sport, crime and astrology, sensational five-cent novelettes, films oozing with sex, and sentimental songs which were composed entirely by mechanical means.

"The proles are not human beings," he said carelessly. "By 2050—earlier, probably—all real knowledge of Oldspeak will have disappeared. The whole literature of the past will have been destroyed. Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Byron—they'll exist only in Newspeak versions, not merely changed into something different, but actually changed into something contradictory of what they used to be."

It was assumed that when he was not working, eating, or sleeping he would be taking part in some kind of communal recreation: to do anything that suggested a taste for solitude, even to go for a walk by yourself, was always slightly dangerous.

What kind of people would control this world had been ... obvious. The new aristocracy was made up for the most part of bureaucrats, scientists, technicians, trade-union organizers, publicity experts, sociologists, teachers, journalists, and professional politicians. These people ... had been shaped and brought together by the barren world of monopoly industry and centralized government. As compared with their opposite numbers in past ages, they were less avaricious, less tempted by luxury, hungrier for pure power, and, above all, more conscious of what they were doing and more intent on crushing opposition.

Even the Catholic Church of the Middle Ages was tolerant by modern standards. Part of the reason for this was that in the past no government had the power to keep its citizens under constant surveillance. The invention of print, however, made it easier to manipulate public opinion, and the film and the radio carried the process further. With the development of television, and the technical advance which made it possible to receive and transmit simultaneously on the same instrument, private life came to an end. ... The possibility of enforcing not only complete obedience to the will of the State, but complete uniformity of opinion on all subjects, now existed for the first time.

What opinions the masses hold, or do not hold, is looked on as a matter of indifference. They can be granted intellectual liberty because they have no intellect. In a Party member, on the other hand, not even the smallest deviation of opinion on the most unimportant subject can be tolerated.

[The vocabulary of Newspeak] was so constructed as to give exact and often very subtle expression to every meaning that a Party member would properly wish to express, while excluding all other meanings and also the possibility of arriving at them by indirect methods. This was done partly by the invention of new words, but chiefly by eliminating undesirable words and by stripping such words as remained of unorthodox meanings.

When Oldspeak had been once and for all superseded, the last link with the past would have been severed. History had already been rewritten, but fragments of the literature of the past survived here and there, imperfectly censored, and so long as one retained one's knowledge of Oldspeak it was possible to read them. In the future such fragments, even if they chanced to survive, would be unintelligible and untranslatable.

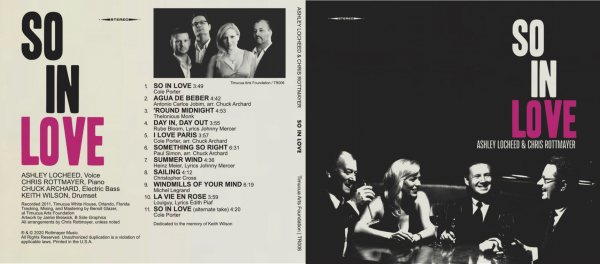

So In Love by Ashley Locheed and Chris Rottmayer (Timucua Arts Foundation 2020)

So In Love by Ashley Locheed and Chris Rottmayer (Timucua Arts Foundation 2020)

At this time in our country, rejoicing with those who rejoice and weeping with those who weep has left me an exhausted mess. Enter: music. I needed a non-political post and this is just the thing.

We've known Ashley for nearly 30 years, and her voice is as beautiful as ever.

I downloaded her album from Amazon. For the physical CD the price (at the moment) is better from her website. I'm told the album is also available on iTunes and other places I don't bother with.

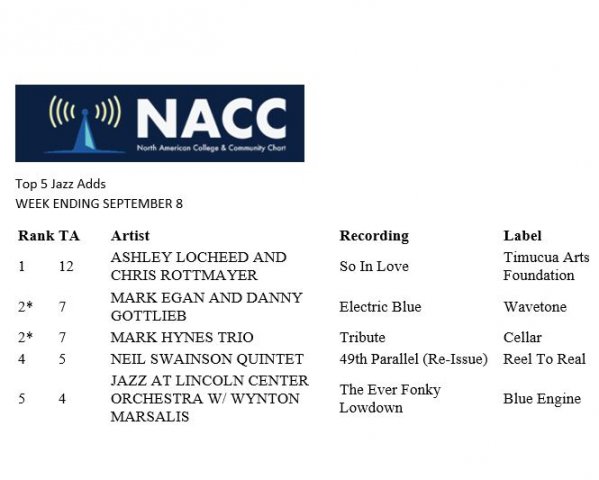

You don't have to take my word for the quality of Ashley's singing. Here, here, here, and here are some reviews. And then there's this:

Congratulations, Ashley and Chris!

Lead Yourself First: Inspiring Leadership Through Solitude by Raymond M. Kethledge and Michael S. Erwin (Bloomsbury 2017)

Lead Yourself First: Inspiring Leadership Through Solitude by Raymond M. Kethledge and Michael S. Erwin (Bloomsbury 2017)

For me, the most impressive chapter of Cal Newport's Digital Minimalism was that on solitude, in which Newport recommends Lead Yourself First. It is a good book, filled with stories of how famous leaders of the past and present (both introverted and highly extroverted) found times of solitude essential to their success. If you've read the former, it is probably not necessary to read this one, Newport having done a good job of condensing the meat in his chapter. But the examples here, which include Dwight D. Eisenhower, Jane Goodall, T. E. Lawrence, Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, Aung San Suu Kyi, Winston Churchill, Martin Luther King, Jr., Pope John Paul II, and many lesser-known leaders, are worth reading in themselves. And for someone in a leadership position it might be even more inspiring.

I did find this to be a somewhat depressing book, despite my appreciation of its content. I find it impossible to read so much about what other people have accomplished and how they work without looking at my own life and thinking, how is it I never learned how to do this?

Somewhere in elementary school, one of my teachers expressed to my parents that he wished I had more interest in being a leader. Teachers are always looking for "leadership qualities." It never occurred to me to want to be a leader ... or a follower, either. So maybe that's where I missed out. Or maybe this is the equivalent of social media envy—the Barbie doll problem. Or maybe the answer lies in the first quotation.

Leading from good to great requires discipline—disciplined people who engage in disciplined thought and who take disciplined action. (from the forward by Jim Collins, p. xiv)

This book illustrates how leaders can—indeed must—be disciplined people who create the quiet space for disciplined thought and summon the strength for disciplined action. It is a message needed now more than ever, else we run the risk of waking up at the end of the year having accomplished little of significance, each year slipping by in a flurry of activity pointing nowhere. (p. xvii, emphasis mine)

I warned you it could be depressing.

To develop ... clarity and conviction of purpose, and the moral courage to sustain it through adversity, requires something that one might not associate with leadership. That something is solitude. (p. xviii)

Genuine leadership means taking the harder path. There are plenty of easier ones: the worn path of convention, smooth and obstacle-free; the fenced path of bureaucracy, where all the hard thinking is done for you, so long as you go wherever it leads; and the parade route of adulation, for those who elevate their followers' approval above all. To depart from any of these paths takes a considered act of will. Not because they are plainly right—more often the opposite is true—but because of the consequences that are sure to follow. The leader who defies convention must bear the disapproval of establishment types, who will try to coerce him morally, and failing that might box his ears. The leader who defies bureaucracy is usually in for harder treatment, as its machinery, given the chance, will run over him with the indifference of a tank. And the leader who makes unpopular decisions must be willing to be unpopular herself, at least for a while. (p. xix)

One of the book's strengths, I believe, is its recognition of what I will call active and passive solitude, and the importance of each. Passive solitude, a clearing of the thoughts commonly (though far from exclusively) associated with meditation, allows people to draw upon the intuition that is so often drowned out by the noise and action of everyday life. ("Be still, and know that I am God.") In active solitude one focusses intently on a particular problem—think Jacob wrestling with the angel. ("I will not let you go unless you bless me.")

The foundation of both analytical and intuitive clarity is an uncluttered mind. (p. 4)

For Eisenhower, the most rigorous way to think about a subject was to write about it. (p. 28)

[Quoting Eisenhower] My days are always full. Even when I think I have a couple of hours to myself, something always happens to upset my plans. But it's right that we should be busy—as long as we can retain time to think. (p. 29)

[Quoting Dena Braeger] We're getting more of everything, but less of what is authentically ourselves. If we spent more time alone, creating something that might not look as amazing [as something from Pinterest] but is more authentic, we'd value ourselves more. (p. 58)

[Quoting Chip Edens] Leaders experience fear in times of turbulence or threat. You become obsessed about worst-case scenarios, fall into despair. That's the easiest way to resolve the conflict. That's when people snap—they quit the job, the marriage is ended, there's no hope. You need to step away from that and give yourself space to process it. (p. 66, emphasis mine)

[Quoting Chip Edens] Differences are a product of ideas. Division is a product of behavior. A community means we live together with differences, but we can't be divided. (p. 66)

[Quoting Dena Braeger] People are so quick to bow to the idea of "staying connected." They aren't conscious of the priorities they're setting with regard to their time. Time is an unrenewable resource. You can't get it back. All these things we've done to exchange information, to access information at our fingertips, have actually taken away our time for restoring the soul. (pp. 133-134)

Solitude has been instrumental to the effectiveness of leaders throughout history, but now they (along with everyone else) are losing it with hardly any awareness of the fact. Before the Information Age—which one could also call the Input Age—leaders naturally found solitude anytime they were physically alone, or when walking from one place to another, or while standing in line. Like at great wave that saturates everything in its path, however, handheld devices deliver immeasurable quantities of information and entertainment that now have virtually everyone instead staring down at their phones. Society did not make a considered choice to surrender the bulk of its time for reflection in favor of time spent reading tweets or texts. (p. 181)

A leader must strike a balance between solitude and interaction with others, but leaders (along with everyone else) face considerable social pressure to skew the balance toward interaction. The term "loner" is usually a pejorative, often directed at people who spend only a fraction of their time alone. And in many offices the culture is to gather in herds—not only in meetings but at cake parties, lunch, and various events outside work. ... This same culture also finds physical manifestation, in open-office plans and large rooms full of cubicles. (p. 182)

If you plan to use solitude to think about a specific issue, you should identify that issue in advance and briefly review any materials you think especially relevant. That will get your mind processing the issue beforehand, which often allows insights—sometimes analytical, sometimes intuitive—to come more quickly when you do think about it. (pp. 184-185)

Extroverts gain energy from interaction with others, while introverts lose it. And introverts gain energy from solitude, while extroverts lose it. ... But these energy transfers have little to do with how extroverts and introverts actually perform in these settings. Introverts can excel in social settings; extroverts can excel at thinking alone. The limitation is simply that members of each group can spend only so much time out of their element before they need to recharge. (p. 185)

In some quarters there is a "fear of missing out": a fear that, if one unplugs from e-mail or news services or social media even for a few hours, they'll be less current (a few hours less, to be exact) than their peers. And indeed that is true. But tracking all these inputs is surrender to the Lilliputians. One simply cannot engage in anything more than superficial thought when cycling back and forth between these tweets and work. And most of the inputs are piecemeal, and thus worthless anyway. As with our obsession with smartphones, one needs to make a choice about whether to engage in this kind of practice. And no one serious about his responsibilities will choose to engage in it. (p. 186)

Here's a 15-minute TED talk by Raymond Kethledge that will give you another taste of these ideas.

I would just add two comments.

(1) The quote he attributes to Viktor Frankl at about 10:10 is probably not by him (see this discussion), not that that devalues the point.

(2) At about 11:00 he states, "Moral courage is what we need when we're subject to moral criticism. Moral criticism is when someone says, 'You're not simply mistaken because of what you believe or what you choose to do, but ... you're a bad person because of those things.'" That, ladies and gentlemen, sums up the problem with discourse today.

Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World by Cal Newport (Portfolio/Penguin 2019)

Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World by Cal Newport (Portfolio/Penguin 2019)

Janet recommended this one to me, and after checking out Newport's TED talk, "Why You Should Quit Social Media," I decided to reserve it at the library. I had to wait in line; maybe more than a few people are rethinking Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Old Uncle Tom Cobleigh and all.

Digital Minimalism is divided into two parts: Foundations, and Practices. I read through Foundations easily, able to enjoy the book without pasting sticky tabs all over it. For me, this is like going somewhere and not taking pictures. Those sticky notes represent text that I will later laboriously transcribe for my reviews. As with the photos, something is gained but something is lost. I was enjoying the book and anticipating an easy review.

Then I hit Practices. Or Practices hit me.

The first chapter of that section, "Spend Time Alone," is about solitude deprivation. I could have sticky-noted the whole chapter. Here is me, restraining myself:

Everyone benefits from regular doses of solitude, and, equally important, anyone who avoids this state for an extended period of time will ... suffer. ... Regardless of how you decide to shape your digital ecosystem, you should give your brain the regular doses of quiet it requires to support a monumental life. (pp. 91-92).

[Raymond] Kethledge is a respected judge serving on the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, and [Michael] Erwin is a former army officer who served in both Iraq and Afghanistan. ... [Their book on the topic of solitude], Lead Yourself First ... summarizes, with the tight logic you expect from a federal judge and former military officer, [their] case for the importance of being alone with your thoughts. Before outlining their case, however, the authors start with what is arguably one of their most valuable contributions, a precise definition of solitude. Many people mistakenly associate this term with physical separation—requiring, perhaps, that you hike to a remote cabin miles from another human being. This flawed definition introduces a standard of isolation that can be impractical for most to satisfy on any sort of a regular basis. As Kethledge and Erwin explain, however, solitude is about what’s happening in your brain, not the environment around you. Accordingly, they define it to be a subjective state in which your mind is free from input from other minds. (pp. 92-93)

You can enjoy solitude in a crowded coffee shop, on a subway car, or, as President Lincoln discovered at his cottage, while sharing your lawn with two companies of Union soldiers, so long as your mind is left to grapple only with its own thoughts. On the other hand, solitude can be banished in even the quietest setting if you allow input from other minds to intrude. In addition to direct conversation with another person, these inputs can also take the form of reading a book, listening to a podcast, watching TV, or performing just about any activity that might draw your attention to a smartphone screen. Solitude requires you to move past reacting to information created by other people and focus instead on your own thoughts and experiences—wherever you happen to be. (pp. 93-94).

Regular doses of solitude, mixed in with our default mode of sociality, are necessary to flourish as a human being. It’s more urgent now than ever that we recognize this fact, because ... for the first time in human history solitude is starting to fade away altogether. (p. 99)

The concern that modernity is at odds with solitude is not new. ... The question before us, then, is whether our current moment offers a new threat to solitude that is somehow more pressing than those that commentators have bemoaned for decades. ... To understand my concern, the right place to start is the iPod revolution that occurred in the first years of the twenty-first century. We had portable music before the iPod ... but these devices played only a restricted role in most people’s lives—something you used to entertain yourself while exercising, or in the back seat of a car on a long family road trip. If you stood on a busy city street corner in the early 1990s, you would not see too many people sporting black foam Sony earphones on their way to work. By the early 2000s, however, if you stood on that same street corner, white earbuds would be near ubiquitous. The iPod succeeded not just by selling lots of units, but also by changing the culture surrounding portable music. It became common, especially among younger generations, to allow your iPod to provide a musical backdrop to your entire day—putting the earbuds in as you walk out the door and taking them off only when you couldn’t avoid having to talk to another human. (pp. 99-100).

This transformation started by the iPod, however, didn’t reach its full potential until the release of its successor, the iPhone.... Even though iPods became ubiquitous, there were still moments in which it was either too much trouble to slip in the earbuds (think: waiting to be called into a meeting), or it might be socially awkward to do so (think: sitting bored during a slow hymn at a church service). The smartphone provided a new technique to banish these remaining slivers of solitude: the quick glance. (p. 101)

When you avoid solitude, you miss out on the positive things it brings you: the ability to clarify hard problems, to regulate your emotions, to build moral courage, and to strengthen relationships. (p. 104)

Eliminating solitude also introduces new negative repercussions that we’re only now beginning to understand. A good way to investigate a behavior’s effect is to study a population that pushes the behavior to an extreme. When it comes to constant connectivity, these extremes are readily apparent among young people born after 1995—the first group to enter their preteen years with access to smartphones, tablets, and persistent internet connectivity. ... If persistent solitude deprivation causes problems, we should see them show up here first. ...

The head of mental health services at a well-known university ... told me that she had begun seeing major shifts in student mental health. ... Seemingly overnight the number of students seeking mental health counseling massively expanded, and the standard mix of teenage issues was dominated by something that used to be relatively rare: anxiety. ... The sudden rise in anxiety-related problems coincided with the first incoming classes of students that were raised on smartphones and social media. She noticed that these new students were constantly and frantically processing and sending messages. ...

[San Diego State University psychology professor Jean Twenge observed that] young people born between 1995 and 2012 are ... on the brink of the worst mental-health crisis in decades. ... [She] made it clear that she didn’t set out to implicate the smartphone: “It seemed like too easy an explanation for negative mental-health outcomes in teens,” but it ended up the only explanation that fit the timing. Lots of potential culprits, from stressful current events to increased academic pressure, existed before the spike in anxiety.... The only factor that dramatically increased right around the same time as teenage anxiety was the number of young people owning their own smartphones. ...

When journalist Benoit Denizet-Lewis investigated this teen anxiety epidemic in the New York Times Magazine, he also discovered that the smartphone kept emerging as a persistent signal among the noise of plausible hypotheses. “Anxious kids certainly existed before Instagram,” he writes, “but many of the parents I spoke to worried that their kids’ digital habits—round-the-clock responding to texts, posting to social media, obsessively following the filtered exploits of peers—were partly to blame for their children’s struggles.” Denizet-Lewis assumed that the teenagers themselves would dismiss this theory as standard parental grumbling, but this is not what happened. “To my surprise, anxious teenagers tended to agree.” A college student he interviewed at a residential anxiety treatment center put it well: “Social media is a tool, but it’s become this thing that we can’t live without that’s making us crazy.” (pp. 104-107)

The pianist Glenn Gould once proposed a mathematical formula for this cycle, telling a journalist: “I’ve always had a sort of intuition that for every hour you spend with other human beings you need X number of hours alone. Now what that X represents I don’t really know . . . but it’s a substantial ratio.” (p. 111)

The past two decades ... are characterized by the rapid spread of digital communication tools—my name for apps, services, or sites that enable people to interact through digital networks—which have pushed people’s social networks to be much larger and much less local, while encouraging interactions through short, text-based messages and approval clicks that are orders of magnitude less information laden than what we have evolved to expect. ... Much in the same way that the “innovation” of highly processed foods in the mid-twentieth century led to a global health crisis, the unintended side effects of digital communication tools—a sort of social fast food—are proving to be similarly worrisome.(p. 136).

After winning me over with the chapter on solitude deprivation, Newport lost me somewhat with his approach to taming the beasts. The basic problem is that, for a guy who has written several books and has his own blog, he seems to have very little respect for the written word.

Many people think about conversation and connection as two different strategies for accomplishing the same goal of maintaining their social life. This mind-set believes that there are many different ways to tend important relationships in your life, and in our current modern moment, you should use all tools available—spanning from old-fashioned face-to-face talking, to tapping the heart icon on a friend’s Instagram post.

The philosophy of conversation-centric communication takes a harder stance. It argues that conversation is the only form of interaction that in some sense counts toward maintaining a relationship. This conversation can take the form of a face-to-face meeting, or it can be a video chat or a phone call—so long as it matches Sherry Turkle’s criteria of involving nuanced analog cues, such as the tone of your voice or facial expressions. Anything textual or non-interactive—basically, all social media, email, text, and instant messaging—doesn’t count as conversation and should instead be categorized as mere connection. (p. 147)

I heartily disagree with his lumping e-mail in with "all social media, text, and instant messaging." I will grant that most social media, texts, WhatsApp, IM, and the like are severely limited by the difficulty of creating the message. Phones simply are not designed for high-speed typing, and I don't know about other people's experiences, but for me voice-to-text makes so many errors I spend almost as much time correcting as I would have laboriously pecking out a message on the tiny keyboard. (That's why I much prefer WhatsApp, where I can type my messages on the computer keyboard, to texting, where I can't.) So messages tend to be short, of restricted vocabulary and complexity, and full of nasty abbreviations. But e-mails are simply typed letters that get delivered with much more speed than the mail can achieve. I will grant that you miss the tone-of-voice cues that can be heard over the phone, but I think that's often more than made up for by the ability to both speak and listen without interruption. On the phone, if I turn all my attention to what the other person is saying, there's a long silence when it's my turn to talk while I think of how I want to respond. But if I try to figure that out while the other person is speaking, I'm likely to miss, or mis-interpret what is said. And when I'm speaking, it's more than likely that I will get interrupted before getting out my entire thought, and the conversation will veer off in another direction, leaving my response incomplete and likely mis-understood. E-mail leaves plenty of time for listening, thinking, and responding.

Newport has serious problems with Facebook's "Like" button. I can see his point in some respects.

The “Like” feature evolved to become the foundation on which Facebook rebuilt itself from a fun amusement that people occasionally checked, to a digital slot machine that began to dominate its users’ time and attention. This button introduced a rich new stream of social approval indicators that arrive in an unpredictable fashion—creating an almost impossibly appealing impulse to keep checking your account. It also provided Facebook much more detailed information on your preferences, allowing their machine-learning algorithms to digest your humanity into statistical slivers that could then be mined to push you toward targeted ads and stickier content. (p. 192)

I do get the slot-machine analogy. We all crave (positive) feedback for whatever of ourselves we have put "out there." And the temptation to keep checking is real. It reminds me of the joke from 'way back in the America Online days, in which the person sitting at the computer (no smart phones back then) checks his mail, sees that there is none waiting for him—and immediately checks again. It was funny because that's what so many people did. But I think Newport misunderstands how many of us use the Like button.

In the context of this chapter, however, I don’t want to focus on the boon the “Like” button proved to be for social media companies. I want to instead focus on the harm it inflicted to our human need for real conversation. To click “Like,” within the precise definitions of information theory, is literally the least informative type of nontrivial communication, providing only a minimal one bit of information about the state of the sender (the person clicking the icon on a post) to the receiver (the person who published the post). Earlier, I cited extensive research that supports the claim that the human brain has evolved to process the flood of information generated by face-to-face interactions. To replace this rich flow with a single bit is the ultimate insult to our social processing machinery. (p. 153)

But here's the thing. I don't know anyone who pretends that clicking "Like" or "Love" or "I care" is conversation. However, it is the digital equivalent of one part of a successful conversation: the nod, the smile, the grunt, the frown, the short interjection, which in face-to-face conversation we used as an important lubricant to keep a conversation running smoothly. It hardly communicates any more information than the Facebook buttons; maybe it's little more than a bit—but it's an important bit. It says, "I'm listening, I hear you, I agree, keep talking," or "Wait, what you said confuses me, or angers me," or "I'm sorry, I sympathize."

As soon as easier communication technologies were introduced—text messages, emails—people seemed eager to abandon this time-tested method of conversation for lower-quality connections (Sherry Turkle calls this effect “phone phobia”). (p. 160)

Guilty as charged, but there's no need for Newport (or Turkle) to be snarky about it. I'm hardly alone, and there's ample evidence that phone phobia is attached to the same set of genes that makes me like mathematics. I love the (true) story a colleague told of a bunch of math grad students who decided to order pizza. Every one of them hemmed and hawed and delayed making the order, until the wife of one of the mathematicians, herself a grad student in philosophy, sighed, "For Pete's sake!" and called the restaurant. Text-based communication is a real boon to people like us. Call it a disability if you like—and then remember that you shouldn't mock or discriminate against people with disabilities.

Fortunately, there’s a simple practice that can help you sidestep these inconveniences and make it much easier to regularly enjoy rich phone conversations. I learned it from a technology executive in Silicon Valley who innovated a novel strategy for supporting high-quality interaction with friends and family: he tells them that he’s always available to talk on the phone at 5:30 p.m. on weekdays. There’s no need to schedule a conversation or let him know when you plan to call—just dial him up. As it turns out, 5:30 is when he begins his traffic-clogged commute home in the Bay Area. He decided at some point that he wanted to put this daily period of car confinement to good use, so he invented the 5:30 rule. The logistical simplicity of this system enables this executive to easily shift time-consuming, low-quality connections into higher-quality conversation. If you write him with a somewhat complicated question, he can reply, “I’d love to get into that. Call me at 5:30 any day you want.” Similarly, when I was visiting San Francisco a few years back and wanted to arrange a get-together, he replied that I could catch him on the phone any day at 5:30, and we could work out a plan. When he wants to catch up with someone he hasn’t spoken to in a while, he can send them a quick note saying, “I’d love to get up to speed on what’s going on in your life, call me at 5:30 sometime.” ... He hacked his schedule in such a way that eliminated most of the overhead related to conversation and therefore allowed him to easily serve his human need for rich interaction. (pp. 161-162)

I have to say, that strikes me as more selfish than clever. It's saying to everyone else that he will only communicate with them through his own preferred medium. Granted, it's his right to do so, and maybe he's learned that that's the best way he can get the most accomplished. But I'd have to be pretty desperate to call someone who I knew was going to be driving while he is talking with me. Either he's not going to be giving me his full attention, or he's not going to be giving the other cars on the road his full attention, neither one of which strikes me as ideal. And if I have a complicated question, I definitely want the response to be by written word, where there's a record of what was said, and more chance of getting a well thought out response.

I’ve seen several variations of this practice work well. Using a commute for phone conversations, like the executive introduced above, is a good idea if you follow a regular commuting schedule. It also transforms a potentially wasted part of your day into something meaningful. Coffee shop hours are also popular. In this variation, you pick some time each week during which you settle into a table at your favorite coffee shop with the newspaper or a good book. The reading, however, is just the backup activity. You spread the word among people you know that you’re always at the shop during these hours with the hope that you soon cultivate a rotating group of regulars that come hang out. ... You can also consider running these office hours once a week during happy hour at a favored bar. (pp. 162-163)

<Shudder> Really? I'm supposed to go to the expense, inconvenience, and annoyance of sitting around at a coffee shop or bar on spec, just hoping a friend shows up? And expect my friends to be willing to pay an insane amount for a cup of coffee just to talk with me? Here, and in many other places in Digital Minimalism, you can tell that Newport is an extrovert—with plenty of spare cash—and friends who are the same.

And anyway, whatever happened to visiting people in their homes? One friend of ours decided to quit Facebook, and in her final message invited anyone in town to drop by her house for tea. I could get into that. If you're willing to get out and drive to a restaurant, come instead and knock at our door. You'll be more than welcome and none one of us will have to buy an expensive drink. (This pandemic won't last forever.)

[In the early 20th century, Arnold Bennett, author of How to Live on 24 Hours a Day, speaking of leisure activities] argues that these hours should instead be put to use for demanding and virtuous leisure activities. Bennett, being an early twentieth-century British snob, suggests activities that center on reading difficult literature and rigorous self-reflection. In a representative passage, Bennett dismisses novels because they “never demand any appreciable mental application.” A good leisure pursuit, in Bennett’s calculus, should require more “mental strain” to enjoy (he recommends difficult poetry). (p. 175)

Newport approves of the idea that "the value you receive from a pursuit is often proportional to the energy invested." But then he adds,

For our twenty-first-century purposes, we can ignore the specific activities Bennett suggests. (p. 175)

And what, pray tell, is snobbish or unreasonable about literature and poetry?

Newport has a lot to say about the value of craft: of woodworking, or renovating a bathroom, or repairing a motorcycle, or knitting a sweater. He includes musical performances as well. But—and I find this odd for an author—he seems to have little respect for creating books. Would it be a more noble activity if they were typed on an old Remington, or handwritten? He similarly discounts composing music using a computer as less worthwhile than playing a guitar. I don't buy it.

The following story is for our two oldest grandsons, who have a way of picking up and enjoying construction skills.

[Pete's] welding odyssey began in 2005. At the time, he was building a custom home. ... The house was modern so Pete integrated some custom metalwork into his design plan, including a beautiful custom steel railing on the stairs.

The design seemed like a great idea until Pete received a quote from his metal contractor for the work: it was for $15,800, and Pete had budgeted only $4,000. “If this guy is billing out his metalworking time at $75.00 an hour, that’s a sign that I need to finally learn the craft myself,” Pete recalls thinking at the time. “How hard can it be?” In Pete’s hands, the answer turned out to be: not that hard.

Pete bought a grinder, a metal chop saw, a visor, heavy-duty gloves, and a 120-volt wire-feed flux core welder—which, as Pete explains, is by far the easiest welding device to learn. He then picked some simple projects, loaded up some YouTube videos, and got to work. Before long, Pete became a competent welder—not a master craftsman, but skilled enough to save himself tens of thousands of dollars in labor and parts. (As Pete explains it, he can’t craft a “curvaceous supercar,” but he could certainly weld up a “nice Mad-Max-style dune buggy.”) In addition to completing the railing for his custom home project (for much less than the $15,800 he was quoted), Pete went on to build a similar railing for a rooftop patio on a nearby home. He then started creating steel garden gates and unusual plant holders. He built a custom lumber rack for his pickup truck and fabricated a series of structural parts for straightening up old foundations and floors in the historic homes in his neighborhood. As Pete was writing his post on welding, a metal attachment bracket for his garage door opener broke. He easily fixed it. (pp. 194-195)

If you're wondering where to learn skills needed for simple projects ... the answer is easy. Almost every modern-day handyperson I've spoken to recommends the exact same source for quick how-to lessons: YouTube. (pp. 197-198, emphasis mine)

In the middle of a busy workday, or after a particularly trying morning of childcare, it’s tempting to crave the release of having nothing to do—whole blocks of time with no schedule, no expectations, and no activity beyond whatever seems to catch your attention in the moment. These decompression sessions have their place, but their rewards are muted, as they tend to devolve toward low-quality activities like mindless phone swiping and half-hearted binge-watching. ... Investing energy into something hard but worthwhile almost always returns much richer rewards. (p. 212)

Finally, I can't resist his description of former Kickstarter project called the Light Phone.

Here’s how it works. Let’s say you have a Light Phone, which is an elegant slab of white plastic about the size of two or three stacked credit cards. This phone has a keypad and a small number display. And that’s it. All it can do is receive and make telephone calls—about as far as you can get from a modern smartphone while still technically counting as a communication device.

Assume you’re leaving the house to run some errands, and you want freedom from constant attacks on your attention. You activate your Light Phone through a few taps on your normal smartphone. At this point, any calls to your normal phone number will be forwarded to your Light Phone. If you call someone from it, the call will show up as coming from your normal smartphone number as well. When you’re ready to put the Light Phone away, a few more taps turns off the forwarding. This is not a replacement for your smartphone, but instead an escape hatch that allows you to take long breaks from it. (p. 245).

Despite our areas of disagreement, there's only one really, really annoying section of the book. He spends seven pages on the ideas of someone named Jennifer who "prefers the pronoun 'they/their' to 'she/her'." The ideas are not worth the ensuing confusion between singular and plural. I found myself constantly re-reading trying to figure out who was being referenced in the text.

But I do recommend reading Digital Minimalism. The concept of solitude deprivation alone would make it worthwhile, and the rest of the book is pretty good, too—especially if you're not a phone-phobic, introverted author.

Permalink | Read 2250 times | Comments (6)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Computing: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Social Media: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I read and reviewed The Fall of Heaven in 2017, having no clue at the time how much closer America would come to this perilous situation in just three years. It's time to revisit that review.

Please read this book. It was recommended to me by two Iranian friends who suffered through, and escaped from, the Iranian Revolution. Thus I give it much higher credence than I would a random book off the library shelves. If they say the reporting accords with their own experiences, I believe them. They are highly intelligent and well-educated people.

I cannot overstate how important I think this book to be for here and now in America. Who our Ruhollah Khomeini might be I do not know, but I look at the news and am convinced that the stage set is a close copy of that in Iran 40 years ago, and the script is frighteningly similar.

Those who are fighting for change at any cost need to consider just how high that cost might be.

The Fall of Heaven: The Pahlavis and the Final Days of Imperial Iran by Andrew Scott Cooper (Henry Holt, 2016)

The Fall of Heaven: The Pahlavis and the Final Days of Imperial Iran by Andrew Scott Cooper (Henry Holt, 2016)

People were excited at the prospect of "change."

That was the cry, "We want change."

You are living in a country that is one of the wealthiest and most powerful in the world. You enjoy freedom, education, and health care that was beyond the imagination of the generation before you, and the envy of most of the world. But all is not well. There is a large gap between the rich and the poor, and a widening psychological gulf between rural workers and urban elites. A growing number of people begin to look past the glitter and glitz of the cities and see the strip clubs, the indecent, avant-garde theatrical performances, offensive behavior in the streets, and the disintegration of family and tradition. Stories of greed and corruption at the highest corporate and governmental levels have shaken faith in the country's bedrock institutions. Rumors—with some truth—of police brutality stoke the fears of the population, and merciless criminals freely exploit attempts to restrain police action. The country is awash in information that is outdated, inaccurate, and being manipulated for wrongful ends; the misinformation is nowhere so egregious as at the upper levels of government, where leaders believe what they want to hear, and dismiss the few voices of truth as too negative. Random violence and senseless destruction are on the rise, along with incivility and intolerance. Extremists from both the Left and the Right profit from, and provoke, this disorder, knowing that a frightened and angry populace is easily manipulated. Foreign governments and terrorist organizations publish inflammatory information, fund angry demonstrations, foment riots, and train and arm revolutionaries. The general population hurtles to the point of believing the situation so bad that the country must change—without much consideration for what that change may turn out to bring.

It's 1978. You are in Iran.

I haven't felt so strongly about a book since Hold On to Your Kids. Read. This. Book. Not because it is a page-turning account of the Iranian Revolution of 1978/79, which it is, but because there is so much there that reminds me of America, today. Not that I can draw any neat conclusions about how to apply this information: the complexities of what happened to turn our second-best friend in the Middle East into one of our worst enemies have no easy unravelling. But time has a way of at least making the events clearer, and for that alone The Fall of Heaven is worth reading.

On the other hand, most people don't have the time and the energy to read a densely-packed, 500-page history book. If you're a parent, or a grandparent, or work with children, I say your time would be better spent reading Hold On to Your Kids. But if you can get your hands on a copy of this book, I strongly recommend reading the first few pages: the People, the Events, and the Introduction. That's only 25 pages. By then, you may be hooked, as I was; if not you will at least have been given a good overview of what is fleshed out in the remainder of the book.

A few brief take-aways:

- The road to hell is paved with good intentions. Jimmy Carter is undoubtedly an amazing, wonderful person; as my husband is fond of saying, the best ex-president we've ever had. But in the very moments he was winning his Nobel Peace Prize by brokering the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty at Camp David, he—or his administration—was consigning Iran to the hell that endures today. Thanks to a complete failure of American (and British) Intelligence and a massive disinformation campaign with just enough truth to keep it from being dismissed out of hand, President Carter was led to believe that the Shah of Iran was a monster; America's ambassador to the United Nations, Andrew Young, likened the Shah to Adolf Eichmann, and called Ruhollah Khomeini a saint. Perhaps the Iranian Revolution and its concomitant bloodbath would have happened without American incompetence, disingenuousness, and backstabbing, but that there is much innocent blood on the hands of our kindly, Peace Prize-winning President, I have no doubt.

- There's a reason spycraft is called intelligence. Lack of good information leads to stupid decisions.

- Bad advisers will bring down a good leader, be he President or Shah, and good advisers can't save him if he won't listen.

- The Bible is 100% correct when it likens people to sheep. Whether by politicians, agitators, con men, charismatic religious leaders (note: small "c"), pop stars, advertisers, or our own peers, we are pathetically easy to manipulate.

- When the Shah imposed Western Culture on his people, it came with Western decadence and Hollywood immorality thrown in. Even salt-of-the-earth, ordinary people can only take so much of having their lives, their values, and their family integrity threatened. "It does not do to leave a live dragon out of your calculations."

- The Shah's education programs sent students by droves to Europe and the United States for university educations. This was an unprecedented opportunity, but the timing could have been better. The 1960's and 70's were not sane years on college campuses, as I can personally testify. Instead of being grateful for their educations, the students came home radicalized against their government. In this case, "the Man," the enemy, was the Shah and all that he stood for. Anxious to identify with the masses and their deprivations, these sons and daughters of privilege exchanged one set of drag for another, donning austere Muslim garb as a way of distancing themselves from everything their parents held dear. Few had ever opened a Quran, and fewer still had an in-depth knowledge of Shia theology, but in their rebellious naïveté they rushed to embrace the latest opiate.

- "Suicide bomber" was not a household word 40 years ago, but the concept was there. "If you give the order we are prepared to attach bombs to ourselves and throw ourselves at the Shah's car to blow him up," one local merchant told the Ayatollah.

- People with greatly differing viewpoints can find much in The Fall of Heaven to support their own ideas and fears. Those who see sinister influences behind the senseless, deliberate destruction during natural disasters and protest demonstrations will find justification for their suspicions in the brutal, calculated provocations perpetrated by Iran's revolutionaries. Others will find striking parallels between the rise of Radical Islam in Iran and the rise of Donald Trump in the United States. Those who have no use for deeply-held religious beliefs will find confirmation of their own belief that the only acceptable religions are those that their followers don't take too seriously. Some will look at the Iranian Revolution and see a prime example of how conciliation and compromise with evil will only end in disaster.

- I've read the Qur'an and know more about Islam than many Americans (credit not my knowledge but general American ignorance), but in this book I discovered something that surprised me. Two practices that I assumed marked every serious Muslim are five-times-a-day prayer, and fasting during Ramadan. Yet the Shah, an obviously devout man who "ruled in the fear of God" and always carried a Qur'an with him, did neither. Is this a legitimate and common variation, or the Muslim equivalent of the Christian who displays a Bible prominently on his coffee table but rarely cracks it open and prefers to sleep in on Sundays? Clearly, I have more to learn.

- Many of Iran's problems in the years before the Revolution seem remarkably similar to those of someone who wins a million dollar lottery. Government largess fueled by massive oil revenues thrust people suddenly into a new and unfamiliar world of wealth, in the end leaving them, not grateful, but resentful when falling oil prices dried up the flow of money.

- I totally understand why one country would want to influence another country that it views as strategically important; that may even be considered its duty to its own citizens. But for goodness' sake, if you're going to interfere, wait until you have a good knowledge of the country, its history, its customs, and its people. Our ignorance of Iran in general and the political and social situation in particular was appalling. We bought the carefully-orchestrated public façade of Khomeini hook, line, and sinker; an English translation of his inflammatory writings and blueprint for the establishment of an Islamic republic in Iran came nine years too late, after it was all over. In our ignorance we conferred political legitimacy on the radical Khomeini while ignoring the true leaders of the majority of Iran's Shiite Muslims. The American ambassador and his counterpart from the United Kingdom, on whom the Shah relied heavily in the last days, confidently gave him ignorant and disastrous advice. Not to mention that it was our manipulation of the oil market (with the aid of Saudi Arabia) that brought on the fall in oil prices that precipitated Iran's economic crisis.

- The bumbling actions of the United States, however, look positively beatific compared with the works of men like Muammar Gaddafi of Libya, and Yasser Arafat and his Palestine Liberation Organization, who funded, trained, and armed the revolutionaries.

I threw out the multitude of sticky notes with which I marked up the book in favor of one long quotation from the introduction. It matters to me because I heard and absorbed the accusations against the Shah, and even thought Khomeini was acting out of a legitimate complaint with regard to the immorality of some aspects of American culture. Not that I paid much attention to world events at the time of the Revolution, being more concerned with my job, our first house, a visit to my in-laws in Brazil, and the birth of our first child. But I was deceived by the fake news, and I'm glad to have a clearer picture at last.

The controversy and confusion that surrounded the Shah's human rights record overshadowed his many real accomplishments in the fields of women's rights, literacy, health care, education, and modernization. Help in sifting through the accusations and allegations came from a most unexpected quarter, however, when the Islamic Republic announced plans to identify and memorialize each victim of Pahlavi "oppression." But lead researcher Emad al-Din Baghi, a former seminary student, was shocked to discover that the could not match the victims' names to the official numbers: instead of 100,000 deaths Baghi could confirm only 3,164. Even that number was inflated because it included all 2,781 fatalities from the 1978-1979 revolution. The actual death toll was lowered to 383, of whom 197 were guerrilla fighters and terrorists killed in skirmishes with the security forces. That meant 183 political prisoners and dissidents were executed, committed suicide in detention, or died under torture. [No, I can't make those numbers add up right either, but it's close enough.] The number of political prisoners was also sharply reduced, from 100,000 to about 3,200. Baghi's revised numbers were troublesome for another reason: they matched the estimates already provided by the Shah to the International Committee of the Red Cross before the revolution. "The problem here was not only the realization that the Pahlavi state might have been telling the truth but the fact that the Islamic Republic had justified many of its excesses on the popular sacrifices already made," observed historian Ali Ansari. ... Baghi's report exposed Khomeini's hypocrisy and threatened to undermine the vey moral basis of the revolution. Similarly, the corruption charges against the Pahlavis collapsed when the Shah's fortune was revealed to be well under $100 million at the time of his departure [instead of the rumored $25-$50 billion], hardly insignificant but modest by the standards of other royal families and remarkably low by the estimates that appeared in the Western press.

Baghi's research was suppressed inside Iran but opened up new vistas of study for scholars elsewhere. As a former researcher at Human Rights Watch, the U.S. organization that monitors human rights around the world, I was curious to learn how the higher numbers became common currency in the first place. I interviewed Iranian revolutionaries and foreign correspondents whose reporting had helped cement the popular image of the Shah as a blood-soaked tyrant. I visited the Center for Documentation on the Revolution in Tehran, the state organization that compiles information on human rights during the Pahlavi era, and was assured by current and former staff that Baghi's reduced numbers were indeed credible. If anything, my own research suggested that Baghi's estimates might still be too high. For example, during the revolution the Shah was blamed for a cinema fire that killed 430 people in the southern city of Abadan; we now know that this heinous crime was carried out by a pro-Khomeini terror cell. Dozens of government officials and soldiers had been killed during the revolution, but their deaths were also attributed to the Shah and not to Khomeini. The lower numbers do not excuse or diminish the suffering of political prisoners jailed or tortured in Iran in the 1970s. They do, however, show the extent to which the historical record was manipulated by Khomeini and his partisans to criminalize the Shah and justify their own excesses and abuses.

As I neared the end of my C. S. Lewis retrospective—reading (mostly re-reading) all the books we own by or about the prolific author—I was challenged by my friend, The Occasional CEO, to relate a few of the most significant things I have learned from Lewis. I began with the idea of trying to distill a Top Five from his many areas of influence in my life.

It soon became clear that of everything I have learned from Lewis—from faith to literature to history to the changing meaning of words to the critical importance of one's model of the universe—two stood out, orders of magnitude greater than the rest.

All is gift. I am Oyarsa not by His gift alone but by our foster mother’s, not by hers alone but by yours, not by yours alone but my wife’s—nay, in some sort, by gift of the very beasts and birds. Through many hands, enriched with many different kinds of love and labor, the gift comes to me. It is the Law. The best fruits are plucked for each by some hand that is not his own.” (Perelandra)

The first gift I received from C. S. Lewis was his Narnia stories. I was introduced to them in mid-elementary school: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe was a gift from my mother, who brought it to me in a stack of books from the library when I was sick in bed. The remainder of the series came about two years later, a gift from a neighbor, who owned all seven and shared them around our group of friends. I was delighted, enthralled. However, my attempt to find similar delight in his other fiction was at the time unsuccessful. I tried the first of his Space Trilogy, but I was a hard-core science fiction fan—Asimov, Heinlein, Clarke—and Out of the Silent Planet was not sufficiently science-based for me. One of Lewis's earliest books, it lacks the beauty and enchantment of the Narnia stories, and was intended for an adult audience. I have since come to enjoy it, but I wasn't ready then.

I rediscovered Narnia in college, thanks to the University of Rochester's Education Library, which was well-stocked with children's books. There I also first encountered Mere Christianity: the gift of my roommate, and my introduction to Lewis's nonfiction. To my shock, there I discovered that all the delight—the goodness, truth, and beauty—that I had encountered in Narnia was for Lewis an expression of reality, a reality far greater than he could depict, even in fantasy. I came later to respect the background in Christianity I had received in my childhood, but it was through Lewis and Narnia that the reality of God began to make sense to me.

This is the first and great gift, and the second is like unto it.

I went on to read more of Lewis's non-fiction, and to gain from it, but his next pivotal gift came many years later, through a friend—all is gift—who shared with me Lewis's George MacDonald: An Anthology.

If Narnia had shown me a God who made sense of the world, MacDonald showed me a God I could love.

George MacDonald is another author I had met before—as a child through his Curdie books and At the Back of the North Wind—but I'd never followed through to find what else he might have written. To be fair to myself, his other books weren't easy to find back then.

Of MacDonald, Lewis wrote,

In making these extracts I have been concerned with MacDonald not as a writer but as a Christian teacher. If I were to deal with him as a writer, a man of letters, I should be faced with a difficult critical problem. If we define Literature as an art whose medium is words, then certainly MacDonald has no place in its first rank—perhaps not even in its second. There are indeed passages, many of them in this collection, where the wisdom and (I would dare to call it) the holiness that are in him triumph over and even burn away the baser elements in his style: the expression becomes precise, weighty, economic; acquires a cutting edge. But he does not maintain this level for long. The texture of his writing as a whole is undistinguished, at times fumbling. Bad pulpit traditions cling to it; there is sometimes a nonconformist verbosity, sometimes an old Scotch weakness for florid ornament (it runs right through them from Dunbar to the Waverly Novels), sometimes an oversweetness picked up from Novalis. But this does not quite dispose of him even for the literary critic. What he does best is fantasy—fantasy that hovers between the allegorical and the mythopoeic. And this, in my opinion, he does better than any man. (Unless otherwise noted, all quotations are from Lewis's preface to George MacDonald, An Anthology.)

MacDonald's works can be divided roughly into three parts, though they overlap: the fantasy that so impressed Lewis; books of sermons; and his many adult novels—the craft of which left Lewis so unimpressed—which served both to feed his family of thirteen and as vehicles for reaching a wider audience with his preaching. The last sounds dreary, but in reality the preaching is what makes his novels shine. (Those who know my lack of appreciation for most sermons will recognize the peculiarity of such a statement coming from me.)

Having been reawakened to MacDonald by Lewis's Anthology, I looked around for more, and the best I could find were modern re-workings of his novels, some by Michael R. Phillips and some by Dan Hamilton. I give credit to both authors for their obvious respect for MacDonald, and their faithfulness to his ideas, even though in their efforts they exaggerated the parts I like least from the originals (the Romantic elements) and reduced the best (the preaching). The library had most of them, and I wolfed them down.

Most of my extracts are taken from the three volumes of Unspoken Sermons. My own debt to this book is almost as great as one man can owe to another.

The next contributor to my journey was a church secretary who had obtained photocopies of all three Unspoken Sermons books, which she graciously shared. I wonder if the generations who grew up with easy access to a universe of electronic resources can even imagine how valuable bound photocopies could be. Or what an incredible gift it was to the world when, in the 1990's, Johannesen began republishing all of MacDonald's works, in beautifully-crafted sets. All of these treasures were given to me, over several years of birthdays and Christmases, by my father. He himself had no particular appreciation of MacDonald—I doubt he read any of the books—but a great deal of love for his children and grandchildren, for whom I consider the collection a legacy. Now, Kindle versions of almost all of MacDonald's works are available at no cost.

I have never concealed the fact that I regarded him as my master; indeed I fancy I have never written a book in which I did not quote from him.

Lewis is not exaggerating the frequency of MacDonald's influence on his own works. Having tackled my MacDonald retrospective first, I easily recognized his ideas and often his words when I encountered them in Lewis.

I know nothing that gives me such a feeling of spiritual healing, of being washed, as to read George MacDonald. (from a letter of Lewis to Arthur Greeves)

I dare not say that he is never in error; but to speak plainly I know hardly any other writer who seems to be closer, or more continually close, to the Spirit of Christ Himself.

What greater endorsement could there be?

Lewis was puzzled as to how people could idolize him and ignore MacDonald. I have some ideas. MacDonald's books were old, even then—he had died before Lewis turned seven—and our society's "chronological snobbery" was well established. Although full of gold, many of his books are difficult to read, even those not laden with Scottish dialect. I can now say that it's well worth the effort, and the reading and understanding get much easier with practice. But I can't forget that I had actually encountered MacDonald's novels years before, deep in the stacks of our main college library. But apparently this, too, had to wait to be a gift rather than my own choice: to my everlasting embarrassment, I turned aside from those unattractive, ancient, brown, and dusty tomes. Perhaps it was the library's revenge that I later became a genealogist, whose blood now quickens at the mere scent of such books.

Then, too, from the beginning MacDonald was plagued by charges of heresy and branded "Universalist" for his belief that, in the end, God's love would triumph. Lewis did not see him that way, but it led (and still leads) some to dismiss MacDonald out of hand.

Reaction against early [strict Scottish Calvinist] teachings might ... have very easily driven him into a shallow liberalism. But it does not. He hopes, indeed, that all men will be saved; but that is because he hopes that all will repent.

Nowhere else outside the New Testament have I found terror and comfort so intertwined.

Inexorability—but never the inexorability of anything less than love—runs through [MacDonald's thought] like a refrain; "escape is hopeless"—"agree quickly with your adversary"—"compulsion waits behind"—"the uttermost farthing will be exacted." Yet this urgency never becomes shrill. All the sermons are suffused with a spirit of love and wonder which prevents it from doing so. MacDonald shows God threatening, but (as Jeremy Taylor says) "He threatens terrible things if we will not be happy."

The effect of C. S. Lewis's writings on my thinking is incalculable, and not just from his most popular books. Who would have guessed, for example, that I would give a five-star rating to Studies in Words—a book on philology, addressed to scholars, of which I understood less than half? But I was fascinated, and my eyes were opened to the pernicious habit (especially common among both literary critics and high school English teachers) of simply seeking meaning in what we read, instead of seeking what the author meant by his words and what his contemporary audience understood him to be saying.

There's no doubt that Lewis was quirky, humble, and absolutely brilliant—all the more brilliant that so many of his writings were written to be accessible to the ordinary British public, yet there's no hint of condescension. I could start my Lewis retrospective over again from the beginning and learn a lot more.

But for all that, Lewis's greatest influence on my life came less through my mind than through my spirit. Lewis said that reading MacDonald's Phantastes "baptized his imagination." The Narnia books first, and then George MacDonald directly, did the same for me.

This surprising realization came nearly sixty years after my first encounter with The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, and was itself a gift—thanks to my friend's challenge.

The Alto Wore Tweed (Liturgical Mysteries #1) by Mark Schweizer (St. James Music Press, 2002)

The Alto Wore Tweed (Liturgical Mysteries #1) by Mark Schweizer (St. James Music Press, 2002)

This book is just for fun. If there is something of redeeming social value about it, I didn't notice, but I laughed longer and harder than I have over a book in a long time. Our choir director introduced me to the series—we get some of our anthems from St. James Press—and it was also recommended by other choir members.

The protagonist is an Episcopal church music director who is also a detective and a writer of "hard-boiled" detective fiction. I'm not a fan of that school of detective stories, but I know enough about it to get some of the jokes. And as a member of an Episcopal church choir, I can tell you that the author hits just close enough to the truth to be really funny. What someone without this background would think, I don't know.

I was warned that I'd have to not mind the "religious irreverence," but it's not irreverent toward God, and a bit of irreverence toward choir and church foibles is probably not a bad thing. Some of the situations and humor are "adult" (though I hate to use that term) but not graphic. I have a very low tolerance for such things and still enjoyed the book a lot, so I doubt anyone else would have a problem; I mention it merely as a grandchild warning to parents. More to the point, I don't think any of our grandchildren have enough experience as yet to appreciate the satire.

In October 2018 I began another adventure in reading—as close to consecutively as was reasonable—all the works we own by or about a particular author. Previous authors have included the highbrow, the lowbrow, and the in-between: William Shakespeare (plays only, read or viewed), George MacDonald, J. R. R. Tolkien, Miss Read (Dora Jesse Saint), and all the Rick Brant Science-Adventure series of John Blaine (Harold L. Goodwin). This time I tackled C. S. Lewis, the number of whose books on our shelves is exceeded only by George MacDonald's. I concluded the project 21 months later, in July 2020. Needless to say there were a lot of non-Lewis books interspersed with these. Even C. S. Lewis is none the worse for a break.

Here's the whole list, in the order in which I completed them. The links are to my own posts about the books.

Ratings Guide: 0 to 5 ★s reflects how much I liked it (worst to best); 0 to 3 ☢s represents a content advisory (mildest to strongest). I make no claim to consistency, as I couldn't keep the ratings from being affected by both my mood at the time of reading and what I had read before.

- C. S. Lewis: Images of His World, by James Riordan and Pauline Baynes ★★★

- C. S. Lewis: A Biography ★★★

- Spirits in Bondage ★★

- The Pilgrim's Regress ★★★

- Space Trilogy 1: Out of the Silent Planet ★★★★★

- The Problem of Pain ★★★★★

- The Dark Tower and Other Stories, edited by Walter Hooper ★★ ☢

- Planet Narnia: The Seven Heavens in the Imagination of C. S. Lewis, by Michael Ward ★★★★★

- Poems ★★★★

- Preface to Paradise Lost ★★★

- The Screwtape Letters ★★★★★

- Space Trilogy 2: Perelandra ★★★★★

- The Abolition of Man ★★★★★

- The Weight of Glory ★★★★★

- Space Trilogy 3: That Hideous Strength ★★★★

- The Great Divorce ★★★★★

- Miracles ★★★★★

- Mere Christianity ★★★★★

- On Stories: And Other Essays on Literature ★★★★★

- Past Watchful Dragons, by Walter Hooper ★★★

- C. S. Lewis on Scripture, by Michael J. Christensen ★★★

- A Book of Narnians: The Lion, the Witch, and the Others, by James Riordan and Pauline Baynes ★★★

- The Chronicles of Narnia 1: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe ★★★★★

- The Chronicles of Narnia 2: Prince Caspian ★★★★★

- The Chronicles of Narnia 3: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader ★★★★★

- The Chronicles of Narnia 4: The Silver Chair ★★★★★

- The Chronicles of Narnia 5: The Horse and His Boy ★★★★★

- The Chronicles of Narnia 6: The Magician's Nephew ★★★★★

- The Chronicles of Narnia 7: The Last Battle ★★★★★

- Smoke on the Mountain, by Joy Davidman (not by or about Lewis, but it seemed appropriate, as she was his wife) ★★★

- Surprised by Joy ★★★★

- Till We Have Faces ★★★★

- The Business of Heaven, edited by Walter Hooper ★★★

- Reflections on the Psalms ★★★★★

- Studies in Words ★★★★★

- The Four Loves ★★★★

- The World's Last Night ★★★★★

- A Grief Observed ★★★★

- An Experiment in Criticism ★★★

- Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer ★★★★

- Letters to Children ★★★★

- C. S. Lewis: A Companion & Guide, by Walter Hooper ★★★★

- The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature (by Lewis, edited by Walter Hooper) ★★★★

- Christian Reflections ★★★★

- Letters to an American Lady ★★★

- Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories ★★★

- God in the Dock ★★★★★

- Surprised By Laughter: The Comic World of C. S. Lewis, by Terry Lindvall ★★

- G. K. Chesterton and C. S. Lewis: The Riddle of Joy, edited by Michael H. Macdonald and Andrew A. Tadie ★★★

- The Quotable Lewis, edited by Wayne Martindale and Jerry Root ★★★★