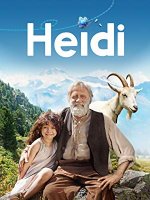

Heidi by Johanna Spyri

Not long ago I had a chance to view this 2017 movie of Heidi. Unfortunately, Netflix doesn't have it, but that link will take you to the Amazon version. The film endeared itself to me immediately because the grandfather is played by Bruno Ganz, whom I first met as the amazing grandfather in Vitus (another great movie set in Switzerland).

I remember having seen a movie version of Heidi many years ago, but which one it was I have no idea. All I remember about it is that this new one struck me as quite different. Having never actually read the book (yes, I'm embarrassed), I decided it was necessary to remedy that omission and learn the truth.

Normally I prefer reading a book before seeing any movie version, so as not to have someone else's ideas and images come between the author and my experience. However, in this case, the movie is good, and true enough to the book that seeing it first is fine—and the movie would be worth seeing for the Swiss scenery and culture alone. If I'd read the book first, I'd probably not have enjoyed the movie as much, because my mental commentary always intrudes: That's not right, that didn't happen, why did they change that scene?, why did they leave out the best parts???

So go ahead, see the movie. But be sure to read the book! There really is a lot to this beautiful story that's left on the cutting room floor for the film. I strongly recommend reading the book, especially for anyone lucky enough to have friends or family in Switzerland. It would be a great read-aloud choice, and the Kindle version is free. Unfortunately, I can't find any information on the translator for the Kindle edition. I like the translation very much, because it's fine English but retains just a little flavor of the German—for example, the neuter gender of das Kind—which adds to the atmosphere. The only time I notice this getting in the way of understanding is that apparently the word for "yawn" is translated "gape," which can lead to some confusion in one chapter. Otherwise, it's just delightful.

It's lovely to be able to recommend a book without reservation!

Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t: Why That Is and What You Can Do about It by Steven Pressfield (Black Irish Entertainment, 2016) (This subtitle is for the Kindle version. The paperback subtitle is And Other Tough-Love Truths to Make You a Better Writer. Don't ask me why.)

Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t: Why That Is and What You Can Do about It by Steven Pressfield (Black Irish Entertainment, 2016) (This subtitle is for the Kindle version. The paperback subtitle is And Other Tough-Love Truths to Make You a Better Writer. Don't ask me why.)

I hate this book. That's why I'm considering buying my own copy.

Our grandson received a Kindle for his birthday, a rite of passage in his family. Fortunately, he didn't mind in the least that it was a used Kindle by the time it was placed in his hands. I took full advantage of the temporary access to his father's library of e-books during the weeks it was in my possession, devouring six books, one of which was this title. Thus I read it quickly, and do not have access to the notes and quotes I would normally have for writing a review. But here's what I remember:

- The language doesn't get any better than the title, and lacks the courtesy of the asterisk. This shouts unprofessionalism as well as rudeness.

- There are 119 chapters in this 208-page book. You can guess the length of most of the chapters, which read more like Facebook posts than book chapters. This was actually handy for reading in the few spare minutes I could snatch during our recent cruise from Budapest to Amsterdam, but it made the book—not the boat ride—choppy and disorienting.

- Pressfield has very definite ideas about how a story must be written, and reading his prescription my immediate reaction was, "If this is the way books are supposed to be written these days, it's no wonder I find very few that I like."

- He sees little to no difference in how to tell a story, whether writing fiction or non-fiction, books, TV, movies or advertising copy. That's another reason for me not to like modern books. There's a reason I far prefer the written word to film.

- Pressfield sprinkles his book liberally with movie references, which of course leaves me completely at a loss as to the point of the illustration he is using.

- He has a style reminiscent of Ann Voskamp, which I know recommends him to many people, but not to me. I find her writing disorienting and not particularly helpful.

- Basically, the book was annoying to read, often confusing, and seemed to speak of a world totally foreign to my own.

So why on earth am I considered purchasing Nobody Wants to Read your Sh*t?

Because I think it has something to say to me. I think I can learn from it.

One place I agree with Pressfield is that all writing is storytelling. Much of speaking is also storytelling. It's a skill everyone should learn, and while I've picked up some experience flying by the seat of my pants, I'm a babe in the woods when it comes to the art itself. Pressfield, who is a successful writer of fiction, history, and self-help books as well as movie and television scripts, clearly knows much that I'm not even aware that I don't know.

- At the most trivial level, learning the art of storytelling will give me a new and fun way to look at books and movies, trying to puzzle out the patterns and techniques used to create the story line.

- Since all writing is storytelling, knowing the techniques—even if I reject some of them—should help me make my own writing more interesting.

- It might even help my speaking, since I've been told more than once that when I try to tell a story without writing it down first, I put in too much unnecessary and confusing detail and background, leaving listeners just wishing that I would get to the point. It's not good storytelling to bore the audience.

Well, I've pretty much convinced myself. Now if Amazon would just run one of their special $1.99 sales....

The Shaping of North America: From Earliest Times to 1763 by Isaac Asimov (Dobson, 1973)

The Birth of the United States: 1763 - 1816 by Isaac Asimov (Dobson, 1974)

Our Federal Union: The United States from 1816 to 1865 by Isaac Asimov (Dobson, 1975)

The Golden Door: The United States from 1865 to 1918 by Isaac Asimov (Dobson, 1977)

Isaac Asimov has always been one of my favorite writers, particularly of science fiction. As a child, I preferred my science fiction "hard"—with lots of plausible science and minimal fantasy—and Asimov, a biochemist, could always be counted on.

Later, I discovered his factual science writing, which if not as exciting was equally well-written and almost as compelling. I found that Asimov could expound on almost any topic, making it both interesting and understandable to the intelligent layman. It was with this in mind that I purchased, soon after they were first published, this series of books on American history. I knew even then that studying history was important, and I hoped that my favorite science writer could undo my school experience and make the subject interesting to me.

Alas, it was only time that finally healed that wound, and these books languished on my shelves for decades. I now find the study of history to be, not only important, but essential—especially in these days when ignorance and disregard of history appear to be growing exponentially. At last, I pulled Asimov's books down from the shelf, hoping for both my own edification and some history books I could recommend for our grandchildren.

The first goal was accomplished easily enough. I'm still impressed with Asimov's ability to start from the beginning and explain the basics of a subject without being condescending, a skill absolutly critical when appealing to bright young minds, and at which so many fail absymally when attempting to write for children.

I was so excited by the books that the only thing that kept me from passing them on immediately to our oldest grandchild was the desire to determine whether or not the author's autograph made the first book too valuable for casual use: To Linda, Isaac Asimov, 25 Sep '81. His comment at the time was, "I don't often get asked to autograph this series." True, the occasion was a gathering of science fiction enthusiasts, but of all the Asimov books I owned, these were the only ones I had in hardcover.

Sadly, no series has so failed of its promise to me since Harry Potter, which I felt peaked at the third or fourth book then went downhill dramatically. I waxed enthusiastic about these history books while I was still in the process of reading them (see How Far Have We Come in 200 Years? and The Art of Writing History). At the time, I wrote, "I highly recommend [this series] despite some obvious biases on the author's part (fairly mild, and unavoidable; that's why we need to read history from several sources). I still recommend it, but with serious qualifications.

Asimov's writing is interesting throughout, and he covers a lot of ground with almost as much thoroughness as could be expected from so broad a survey. I especially enjoyed his explanations of the historical origins of many common words and expressions, such as throwing one's hat in the ring, and gerrymandering.

However, as the series progressed, those author biases grew from mild to—well, perhaps not "Thai hot," but certainly too hot for my taste. When I said Asimov writes without condescension, that was not entirely correct. Of the merely ignorant he is respectful; but of those who disagree with his political and social viewpoints, not so much. For example, when he says of Grover Cleveland that "although a bachelor, he indulged in female company"—the kind of indulgence that resulted in an illegitimate child—he makes sure to add, "To expect anything else would have been ridiculous." A few such gratuitous insults are easily passed over, but as they grew numerous, with the political commentary more and more heavy-handed, reading became tedious.

I'm sorry to say that the series also fails of one more promise, the final sentence of the last book: How that came about will have to be the story of the next volume of this history of the United States. If Asimov ever wrote the final volumes of his series, I have yet to find them. It stops abruptly after World War I.

My recommendation has gone from wildly enthusiastic to lukewarm. These are useful histories, as long as one keeps in mind that they're told from a restricted viewpoint. I'm still looking for authors who can write compelling narratives without including a heavy bias in favor of themselves as the ultimate source of wisdom.

What the Dog Saw, by Malcolm Gladwell (Little, Brown & Co., New York, 2009)

What the Dog Saw, by Malcolm Gladwell (Little, Brown & Co., New York, 2009)

Malcolm Gladwell may not always be right—in fact I'd lay odds that he's often wrong, or at least oversimplifying complex problems—but he's always interesting, and always gives new insight into what we don't know about what we thought we understood. What the Dog Saw is another eclectic collection of the same, covering topics as various as ketchup, the Challenger disaster and how our quest for increasing levels of safety is making the world more dangerous, hair coloring, the Enron scandal, the difference between choking and panicking, the problem of homelessness, the problem of intelligence (both as in spying and as in genius), copyright, and the deleterious health effects for modern women of ovulating and menstruating markedly more than was the norm in most times and places throughout history.

What the Dog Saw is well worth reading. In some ways it reminds me of one of my favorite books, Peter Drucker's Adventures of a Bystander. They're not the same thing at all, but both introduce us to remarkable people with remarkable ways of thinking about the world.

I'll close with just one quote, the one that reminds me not to assume that Malcolm Gladwell knows everything he's talking about.

Taleb was back at the whiteboard. Spitznagel was looking on.. Pallow was idly peeling a banana. Outside, the sun was beginning to settle behind the trees. "You do a conversion to p1 and p2," Taleb said. His marker was once again squeaking across the whiteboard. "We say we have a Gaussian distribution, and you have the market switching from a low-volume regime to a high-volume. P21. P22. You have your igon value." He frowned and stared at his handiwork. The markets were now closed.

Sometimes I wonder if I should have majored in English rather than math in college. No, I don't. I would have been bored to tears and torn my hair out in frustration as an English major. Nonetheless, in paragraphs like this I rarely think about whether or not the math makes sense—unlike my son-in-law, whose brain can't ignore such errors. My brain is more attuned to language, and immediately perked up at "Igon value." There was something odd about it. I might simply have dismissed it as something related to finance about which I knew nothing and cared less, but the mere act of pausing made me pronounce the phrase in my mind. "Oh!" I realized. "He means eigenvalue." Mind you, I can now barely tell an eigenvalue from an iceberg, but I knew immediately that (1) Gladwell's field is not math, or any science that depends on math, and (2) his proofreaders/editors don't know math either. (Or just missed it. As a writer, proofreader, and editor myself, I know that these things happen.) All of this to say, if you're going to write about subjects you don't clearly understand (and we all do that), it's important to have a proofreader who can judge content as well as grammar, spelling, and punctuation.

Shades of Gray by Carolyn Reeder (MacMillan, 1989)

Moonshiner's Son by Carolyn Reeder (MacMillan, 1993)

Foster's War by Carolyn Reeder (MacMillan, 1998)

My oldest grandson recommended Shades of Gray to his mother, who recommended it to me; now I'm recommending it to you. Jonathan eats dense, thousand-page books for breakfast, so this 152-page historical novel must have been no more than a gulp for him, but I'm glad to say that he—like his mother and grandmother—is not too proud to enjoy a good book at any level. These three books are all our library has to offer of Reeder's many offerings.

Shades of Gray is a tale of post-Civil War Virginia, told with sensitivity and, as far as I can tell, historical accuracy. There are difficult moments, and times of courage; of returning good for evil, and standing up for one's beliefs, and recognizing the humanity of someone with whom one disagrees. For all this good edcational value, it's also a great story.

Moonshiner's Son is likewise, and gives a whole new appreciation for Appalachian Mountain culture and several sides of our country's well-meaning, but foolish, experiment with Prohibition.

About Foster's War I can't be so enthusiastic, perhaps because I read it last, but more because it is by far the darkest of the three. Again, there are good moments and bad, and a sensitive treatment of the challenges faced by families living in Southern California at the start of World War II. But it's grim.

Although in all three cases the main character is a boy, I can commend the author for the strong female characters she also includes. What distresses me is my suspicion that she may be working out problems she has had with men in her own life. Three books; three boys afraid of the father or father-figure in their lives, and desperately seeking approval. In Foster's War, the father is downright abusive to his whole family, which tiptoes around trying to avoid "setting him off." Plus, in that book there's a lot more of what I don't like about so many modern children's books: disrespect between siblings, and from older children to younger.

I do like that in Foster's War the author does not eschew the language that was common in that era, e.g. referring to the enemy as "Japs," but merely includes a note that that was then, this is now, and the term is now considered insulting—though I did note that she neglected to make the same explanation about "Krauts," referring to the Germans.

Random question: Why is it that books with content only appropriate for older children are written with such a low reading level?

Shade of Gray and Moonshiner's Son I recommend enthusiastically; Foster's War with qualifications.

The Worst Hard Time by Timothy Egan (Houghon Mifflin, 2006)

The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire that Saved America by Timothy Egan (Houghon Mifflin, 2009)

These two books were a gift from my brother and his family; my sister-in-law has an amazing nose for books. The first is about Dust Bowl times, and the second about the greatest single fire in recorded U. S. history.

In actuality, The Big Burn is more about the U. S. Forest Service, and Teddy Roosevelt's dream of setting aside large areas of wilderness to remain free from development. It didn't exactly work out that way, and the politics of that rocky and acrimonious battle are both enlightening and disgusting. The Worst Hard Time is equally educational.

Timothy Egan writes well, and has packed a great deal of both facts and emotion into these two, rivetting stories. My only complaint is that he lets too much of his own political views show through. All writers are biased, and that's okay, as long as they don't pretend not to be. It's the responsibility of the reader to take in information from multiple sources with competing biases in hopes of getting a glimpse of the truth. But in both books, it's hard not to see Egan's characters as ad hominem attacks on the viewpoints they represent. Somehow, the people he disagrees with are not just wrong, but are also fat, lazy, ignorant, greedy, and have disgusting habits. It's almost funny, but spoils the books a bit. It's as annoying when I agree with his position as when I don't.

Egan also has a tendency to conflate extraordinary hardship and that which was normal for the times and places he writes about. No doubt there were plenty of difficulties living in a sod house, for example, but Egan writes about them as a pampered, modern American would feel if suddenly plunked into that situation. As one of my friends has said, "I grew up in a very poor village, but we didn't know we were poor. It was normal life, and we were happy." Having just finished reading several novels by Miss Read (Dora Jessie Saint), in which the main character extols the virtues of her house's thatched roof, I couldn't help thinking that Timothy Egan would have missed all that, and concentrated on the dirt and the bugs, the mice and the birds' nests. What the Dust Bowl victims went through was horrific, and the damage to the land incalculable—but the failure to recognize the goodness of ordinary life, or of any good ground between greedily rich and grindingly poor, takes away from the story. Think of The Worst Hard Time as the anti-Little House on the Prairie.

That said, both books are still well worth reading for the gripping stories and the history lessons.

A Bridge Too Far (the 1977 movie)

A Bridge Too Far (the 1977 movie)

I've seen the movie before, and read the book—but a long, long time ago. Since we are planning a visit to Arnhem—the place of the bridge that was, tragically, "too far"—it seemed good to take another look at the scenery, and the story.

I'm no fan of war movies, but A Bridge Too Far is well done, and well told. It strikes a good balance, showing both criminal stupidities and heroic actions, deftly avoiding both the Scylla of lurid anti-war films and the Charybdis of sentimental patriotism.

I can't recommend it unreservedly, because of the language, but that's rare and at least reasonable for the situations. As for general content ... well, it's rated PG, but it's 'way too sad and intense for most of our grandchildren. That's too bad, because it's a good history lesson, and some of them will be joining us in Arnhem and will see where the events of World War II's Operation Market Garden took place. At least I can highly recommend that our children see A Bridge Too Far, if they can, and maybe the oldest grandson. Or two, I can't be sure. If one likes to read about fictional battles, as they do, maybe it's not so bad to see a bit of what real war is like.

Reviews of television shows are few and far between here. But last Sunday's NCIS Los Angeles show, Warrior of Peace, deserves mention. (Skip this post if you care about spoilers.)

For all of Hollywood's aggressivly secular, if not outright anti-Christian bias (and I don't deny that), every once in a while there is a show that cuts straight to the heart of the Christian story, without any overt mention of Christianity at all. What the regular NCIS Christmas show of 2014, House Rules, did for Christmas, Warrior of Peace has done for Good Friday. The more I think about it, the more parallels I see, but for certain the basics are all there: The protagonist is taken by governmental authorities and turned over those those who demand his execution. He deliberately refuses rescue and walks calmly into certain torture and death, offering himself in exchange for others who are otherwise condemned to die.

Whether planned thus by the writers/producers, or simply in the Providence of God, it can be no coincidence that Warrior of Peace aired on Palm Sunday.

TODAY, Februay 7, you can get the first two Green Ember books in Kindle format for FREE. Enjoy!

Permalink | Read 2066 times | Comments (0)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The Fall of Heaven: The Pahlavis and the Final Days of Imperial Iran by Andrew Scott Cooper (Henry Holt, 2016)

The Fall of Heaven: The Pahlavis and the Final Days of Imperial Iran by Andrew Scott Cooper (Henry Holt, 2016)

People were excited at the prospect of "change." That was the cry, "We want change."

You are living in a country that is one of the wealthiest and most powerful in the world. You enjoy freedom, education, and health care that was beyond the imagination of the generation before you, and the envy of most of the world. But all is not well. There is a large gap between the rich and the poor, and a widening psychological gulf between rural workers and urban elites. A growing number of people begin to look past the glitter and glitz of the cities and see the strip clubs, the indecent, avant-garde theatrical performances, offensive behavior in the streets, and the disintegration of family and tradition. Stories of greed and corruption at the highest corporate and governmental levels have shaken faith in the country's bedrock institutions. Rumors—with some truth—of police brutality stoke the fears of the population, and merciless criminals freely exploit attempts to restrain police action. The country is awash in information that is outdated, wrong, and being manipulated for wrongful ends; the misinformation is nowhere so egregious as at the upper levels of government, where leaders believe what they want to hear, and dismiss the few voices of truth as too negative. Random violence and senseless destruction are on the rise, along with incivility and intolerance. Extremists from both the Left and the Right profit from, and provoke, this disorder, knowing that a frightened and angry populace is easily manipulated. Foreign governments and terrorist organizations publish inflammatory information, fund angry demonstrations, foment riots, and train and arm revolutionaries. The general population hurtles to the point of believing the situation so bad that the country must change—without much consideration for what that change may turn out to bring.

It's 1978. You are in Iran.

I haven't felt so strongly about a book since Hold On to Your Kids. Read. This. Book. Not because it is a page-turning account of the Iranian Revolution of 1978/79, which it is, but because there is so much there that reminds me of America, today. Not that I can draw any neat conclusions about how to apply this information: the complexities of what happened to turn our second-best friend in the Middle East into one of our worst enemies have no easy unravelling. But time has a way of at least making the events clearer, and for that alone The Fall of Heaven is worth reading.

On the other hand, most people don't have the time and the energy to read a densely-packed, 500-page history book. If you're a parent, or a grandparent, or work with children, I say your time would be better spent reading Hold On to Your Kids. But if you can get your hands on a copy, I strongly recommend reading the first few pages: the People, the Events, and the Introduction. That's only 25 pages. By then, you may be hooked, as I was; if not you will at least have been given a good overview of what is fleshed out in the remainder of the book.

A few brief take-aways:

- The road to hell is paved with good intentions. Jimmy Carter is undoubtedly an amazing, wonderful person; as my husband is fond of saying, the best ex-president we've ever had. But in the very moments he was winning his Nobel Peace Prize by brokering the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty at Camp David, he—or his administration—was consigning Iran to the hell that endures today. Thanks to a complete failure of American (and British) Intelligence and a massive disinformation campaign with just enough truth to keep it from being dismissed out of hand, President Carter was led to believe that the Shah of Iran was a monster; America's ambassador to the United Nations, Andrew Young, likened the Shah to Adolf Eichmann, and called Ruhollah Khomeini a saint. Perhaps the Iranian Revolution and its concomitant bloodbath would have happened without American incompetence, disingenuousness, and backstabbing, but that there is much innocent blood on the hands of our kindly, Peace Prize-winning President, I have no doubt.

- There's a reason spycraft is called intelligence. Lack of good information leads to stupid decisions.

- Bad advisers will bring down a good leader, be he President or Shah, and good advisers can't save him if he won't listen.

- The Bible is 100% correct when it likens people to sheep. Whether by politicians, agitators, con men, charismatic religious leaders (note: small "c"), pop stars, advertisers, or our own peers, we are pathetically easy to manipulate.

- When the Shah imposed Western Culture on his people, it came with Western decadence and Hollywood immorality thrown in. Even salt-of-the-earth, ordinary people can only take so much of having their lives, their values, and their family integrity threatened. "It does not do to leave a live dragon out of your calculations."

- The Shah's education programs sent students by droves to Europe and the United States for university educations. This was an unprecedented opportunity, but the timing could have been better. The 1960's and 70's were not sane years on college campuses, as I can personally testify. Instead of being grateful for their educations, the students came home radicalized against their government. In this case, "the Man," the enemy, was the Shah and all that he stood for. Anxious to identify with the masses and their deprivations, these sons and daughters of privilege exchanged one set of drag for another, donning austere Muslim garb as a way of distancing themselves from everything their parents held dear. Few had ever opened a Quran, and fewer still had an in-depth knowledge of Shia theology, but in their rebellious naïveté they rushed to embrace the latest opiate.

- "Suicide bomber" was not a household word 40 years ago, but the concept was there. "If you give the order we are prepared to attach bombs to ourselves and throw ourselves at the Shah's car to blow him up," one local merchant told the Ayatollah.

- People with greatly differing viewpoints can find much in The Fall of Heaven to support their own ideas and fears. Those who see sinister influences behind the senseless, deliberate destruction during natural disasters and protest demonstrations will find justification for their suspicions in the brutal, calculated provocations perpetrated by Iran's revolutionaries. Others will find striking parallels between the rise of Radical Islam in Iran and the rise of Donald Trump in the United States. Those who have no use for deeply-held religious beliefs will find confirmation of their own belief that the only acceptable religions are those that their followers don't take too seriously. Some will look at the Iranian Revolution and see a prime example of how conciliation and compromise with evil will only end in disaster.

- I've read the Qur'an and know more about Islam than many Americans (credit not my knowledge but general American ignorance), but in this book I discovered something that surprised me. Two practices that I assumed marked every serious Muslim are five-times-a-day prayer, and fasting during Ramadan. Yet the Shah, an obviously devout man who "ruled in the fear of God" and always carried a Qur'an with him, did neither. Is this a legitimate and common variation, or the Muslim equivalent of the Christian who displays a Bible prominently on his coffee table but rarely cracks it open and prefers to sleep in on Sundays? Clearly, I have more to learn.

- Many of Iran's problems in the years before the Revolution seem remarkably similar to those of someone who wins a million dollar lottery. Government largess fueled by massive oil revenues thrust people suddenly into a new and unfamiliar world of wealth, in the end leaving them, not grateful, but resentful when falling oil prices dried up the flow of money.

- I totally understand why one country would want to influence another country that it views as strategically important; that may even be considered its duty to its own citizens. But for goodness' sake, if you're going to interfere, wait until you have a good knowledge of the country, its history, its customs, and its people. Our ignorance of Iran in general and the political and social situation in particular was appalling. We bought the carefully-orchestrated public façade of Khomeini hook, line, and sinker; an English translation of his inflammatory writings and blueprint for the establishment of an Islamic republic in Iran came nine years too late, after it was all over. In our ignorance we conferred political legitimacy on the radical Khomeini while ignoring the true leaders of the majority of Iran's Shiite Muslims. The American ambassador and his counterpart from the United Kingdom, on whom the Shah relied heavily in the last days, confidently gave him ignorant and disastrous advice. Not to mention that it was our manipulation of the oil market (with the aid of Saudi Arabia) that brought on the fall in oil prices that precipitated Iran's economic crisis.

- The bumbling actions of the United States, however, look positively beatific compared with the works of men like Muammar Gaddafi of Libya, and Yasser Arafat and his Palestine Liberation Organization, who funded, trained, and armed the revolutionaries.

- The Fall of Heaven was recommended to me by two Iranian friends who personally suffered through, and escaped from, those terrible times.

I threw out the multitude of sticky notes with which I marked up the book in favor of one long quotation from the introduction. It matters to me because I heard and absorbed the accusations against the Shah, and even thought Khomeini was acting out of a legitimate complaint with regard to the immorality of some aspects of American culture. Not that I paid much attention to world events at the time of the Revolution, being more concerned with my job, our first house, a visit to my in-laws in Brazil, and the birth of our first child. But I was deceived by the fake news, and I'm glad to have a clearer picture at last.

The controversy and confusion that surrounded the Shah's human rights record overshadowed his many real accomplishments in the fields of women's rights, literacy, health care, education, and modernization. Help in sifting through the accusations and allegations came from a most unexpected quarter, however, when the Islamic Republic announced plans to identify and memorialize each victim of Pahlavi "oppression." But lead researcher Emad al-Din Baghi, a former seminary student, was shocked to discover that he could not match the victims' names to the official numbers: instead of 100,000 deaths Baghi could confirm only 3,164. Even that number was inflated because it included all 2,781 fatalities from the 1978-1979 revolution. The actual death toll was lowered to 383, of whom 197 were guerrilla fighters and terrorists killed in skirmishes with the security forces. That meant 183 political prisoners and dissidents were executed, committed suicide in detention, or died under torture. [No, I can't make those numbers add up right either, but it's close enough.] The number of political prisoners was also sharply reduced, from 100,000 to about 3,200. Baghi's revised numbers were troublesome for another reason: they matched the estimates already provided by the Shah to the International Committee of the Red Cross before the revolution. "The problem here was not only the realization that the Pahlavi state might have been telling the truth but the fact that the Islamic Republic had justified many of its excesses on the popular sacrifices already made," observed historian Ali Ansari. ... Baghi's report exposed Khomeini's hypocrisy and threatened to undermine the vey moral basis of the revolution. Similarly, the corruption charges against the Pahlavis collapsed when the Shah's fortune was revealed to be well under $100 million at the time of his departure [instead of the rumored $25-$50 billion], hardly insignificant but modest by the standards of other royal families and remarkably low by the estimates that appeared in the Western press.

Baghi's research was suppressed inside Iran but opened up new vistas of study for scholars elsewhere. As a former researcher at Human Rights Watch, the U.S. organization that monitors human rights around the world, I was curious to learn how the higher numbers became common currency in the first place. I interviewed Iranian revolutionaries and foreign correspondents whose reporting had helped cement the popular image of the Shah as a blood-soaked tyrant. I visited the Center for Documentation on the Revolution in Tehran, the state organization that compiles information on human rights during the Pahlavi era, and was assured by current and former staff that Baghi's reduced numbers were indeed credible. If anything, my own research suggested that Baghi's estimates might still be too high. For example, during the revolution the Shah was blamed for a cinema fire that killed 430 people in the southern city of Abadan; we now know that this heinous crime was carried out by a pro-Khomeini terror cell. Dozens of government officials and soldiers had been killed during the revolution, but their deaths were also attributed to the Shah and not to Khomeini. The lower numbers do not excuse or diminish the suffering of political prisoners jailed or tortured in Iran in the 1970s. They do, however, show the extent to which the historical record was manipulated by Khomeini and his partisans to criminalize the Shah and justify their own excesses and abuses.

I normally don't click on those "sponsored" Facebook posts, but Princess Awesome caught my eye more than once. Pink, purple, twirly, pretty skirts and dresses with dinosaurs, math, trains, space creatures and above all pockets. It's about time. They're pricey, but any company that understands that pockets are essential gets major points in my book.

We are Princess Awesome because butterflies are awesome and so are airplanes. Because monsters are awesome and so are twirly skirts. Because girls are awesome and girls get to decide what it means to be girly.

Me? As a child, I wore pants when I could (still do), and since school required girls to wear dresses or skirts, my mother (wonderful woman!) made them for me and always included pockets. But I have four granddaughters who love dresses, and pink, and purple, and twirling, as well as many things commercial clothing usually reserves for boys. Plus math, which even boys are generally deprived of when it comes to seeing their favorite things on their pajamas. (I designed and special-ordered Joseph's pi shirt.)

Shadowed Paradise by Blair Bancroft (Kone Enterprises, 2011)

Shadowed Paradise by Blair Bancroft (Kone Enterprises, 2011)

Those who know me well will be surprised, not to say shocked, to find me reviewing a romance novel. It is a genre I have never, ever liked. You could say that I never outgrew my opinion that the "mushy stuff" spoils a good story. In the Romance genre, the mushy stuff is the story.

Blair Bancroft is the successful author of more than 30 Romance novels, in a variety of sub-genres. Why did I decide to take the plunge into Romance and read her Shadowed Paradise?

- I sing with her in choir. It seemed rude to claim to be her friend while ignoring the works of her heart.

- I discovered through reading her blog posts that I like the way she writes.

- I decided it was unkind to openly condemn a whole genre without reading at least one representative book.

- The novel is set in Florida.

- The protagonist's name is Claire Langdon.

- The author hooked me by making the first chapter of Shadowed Paradise available on her blog.

- The book is available for only $2.99 in Kindle format, a low-risk investment.

- I've never bought into the "beach read" idea, but hey, I was going to be at the beach. Never mind that I was at the beach with 10 grandchildren, ages 2, 2.5, 4, 4.5, 5.5, 6.5, 7, 9, 11, and 13, putting reading low on the priority list, even for me.

Despite all the destractions, I did manage to start and finish Shadowed Paradise.

Enjoyed

- Being set in a familiar location always makes a book more fun for me. I loathed the book Catcher in the Rye and didn't think much of the movie, Taps, but the fact that they are set in one of my home towns—Wayne, Pennsylvania—gives them a special place in my heart. Shadowed Paradise was much more fun than either of those. I don't know a lot about the West Coast of Florida in particular, but in many ways, Florida is Florida. I especially liked the inclusion of the more historical parts of Florida. Until I moved here, I had no idea how important the cattle industry has been to the state.

- There's the Langdon factor, of course. I don't like Claire much (see below), but Jamie is a good kid.

- Unlike most modern stories (in all media), the sex here includes reference to pregnancy as a possible consequence, which I count a good thing.

- Most important of all is that Blair Bancroft can write. No doubt about that. I find all too many modern publications almost physically painful to read because of poor grammar and worse style. I noted only a few—very few—proofreading errors in Shadowed Paradise; it was a pleasure to be able to enjoy the story without being distracted by the writing.

- Another thing Bancroft does well is revealing her characters through their thoughts. The thought pattern of each is distinct, and the madman's way of thinking is especially chilling.

- The mystery is a good one. It bothers me not in the least that I guessed the murderer (albeit after briefly following a red herring), because there were plenty of fun twists along the way. I'm not a fan of horror stories, and have a not-so-cordial dislike for suspense, but there are some good scenes here. The snake story was especially delightful, and I have it on good authority that it's largely true....

Annoyed

- The profanity. Really, what is it that makes people these days unable to talk without swearing? My parents never cursed, ever. And if their friends did, it was not in my hearing. We grew up, enjoyed books, watched movies, and lived full lives with vocabularies that found no need for such language. So many writers now appear to find the inclusion of profanity necessary for "realism." However, as a reader, I long for the days of, "Aaron gently opened the tattered satchel, peered inside, and swore softly to himself," instead of "... and muttered, 'Oh, shit.'" I get the picture quite clearly with the former (I have both experience and imagination), and the latter causes me to wince. I will make occasional exceptions, but books that cause me pain are not high on my reading list.

- Sex with a near stranger, one with a reputation for frequent sexual encounters with multiple partners, and you don't even think about sexually-transmitted diseases? This makes the responsible attitude toward pregnancy (see above) less impressive.

- The book's attitude toward guns does not ring true. With a murdering manic preying on real estate agents, the agency forbids them to carry guns on the job, even in remote locations. News reporting is suppressed in order to avoid "the whole town stampeding to the gun shops." In my experience, the only thing that sends Floridians stampeding to the gun shops is the threat of further restrictions on the availability of firearms and ammunition. I'd be shocked if many of the people in such a real estate agency didn't already own guns; those who did would certainly put up a good deal of resistance to being asked not to carry them. A murderer won't be much fazed by a cell phone, and a water moccasin not at all.

- Bancroft is too hard on Florida's natural wildlife. Yes, there is the occasional report of an alligator that decides to visit someone's swimming pool, and I did once almost hit one that was crossing the road in front of my car. But our kids grew up camping in the woods and handled without a second thought armadillos wandering through camp, scorpions in their shoes (Florida scorpion bites are painful, but not dangerous), and once a pygmy rattlesnake sunning himself on top of the tent. Given how strong and resourceful a woman the story's protagonist has shown herself to be, having her flee in terror at the sight of a spider (albeit a large one) seemed odd.

- She's a bit hard on Langdons, too. I'm no more happy here with the use of the name than I was when I discovered that Dan Brown's detective was named Robert Langdon. Finding one's name in a book is a special kind of thrill (though maybe the Smiths would disagree), but it's less so when you can in no way identify with the character. Claire is nothing like any Langdon I know. But of course she is who she is because of the genre of the book.

- And that's the main problem. I really do not like Romance novels. The idea is entirely foreign to me of someone being so sex-starved that she would throw herself into bed with a man she's barely met—even if he did save her life. Even without the sex scenes, which fill my mind with images I'd rather be able to forget, the idea of a story driven by romantic love sounds nothing but boring to me. I make exceptions: George MacDonald wrote a number of romantic-in-that-sense stories (the ones C. S. Lewis liked the least), but his philosophies and his love for Scotland make up for his use of the vehicle that put bread into the mouths of his eleven children. Also, one of my favorite Dorothy Sayers stories is Gaudy Night, in which a love story is prominent—saved, again, by the mystery and by Sayers' incredible skill. It is the best compliment I can pay to Shadowed Paradise that some of the scenes reminded me of Gaudy Night.

Shadowed Paradise did not make me think any better of the Romance genre, though I'm very glad I read the book and confess that reading it was an enjoyable experience. I can't see myself seeking out any other Romance novel; it's just not my style.

However ... sometime ... in a weak moment ... maybe. It appears Shadowed Paradise is the first novel in a series....

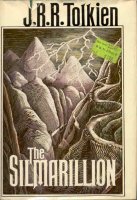

The Silmarillion by J. R. R. Tolkien, edited by Christopher Tolkien (Houghton Mifflin, 1977)

The Silmarillion by J. R. R. Tolkien, edited by Christopher Tolkien (Houghton Mifflin, 1977)

The Silmarillion had been sitting, unread, on my bookshelves for years, even decades. There's really no excuse. I've been a deeply-committed fan of Tolkien's work ever since high school, when my father's unusually prescient sister and her family gave me the Lord of the Rings trilogy one Christmas. If I had the words to explain how much those stories mean to me, I'd be a paid writer myself.

Since then I've read and loved others of Tolkien's works. The Hobbit is also one of my favorites, of course, and I have a special love for Leaf by Niggle. So why did I avoid The Silmarillion? Probably because it is a posthumous work, created by his son, Christopher Tolkien, from unpublished writings. Posthumus and unpublished works always make me nervous, because, like uncut gems, they lack the beauty and wonder that come from the artist's later efforts. I wonder, too: Would the author be pleased to see his ideas come to light after his death, or would he blush and feel his nakedness exposed?

Be that as it may, I knew I had to dust off this book when I discovered that our 13-year-old grandson had read it before me. I'm glad I did. I think Christopher Tolkien did an admirable job, and I loved learning more of the story that occurs before and around the Lord of the Rings books.

I don't recommend The Silmarillion to everyone, however. Those who have told me they just couldn't get past all the names in LOTR haven't seen anything yet. My head is still spinning. What's more, what I dislike most about the LOTR movies—the emphasis on endless battle scenes, and the lack of the amazing character development present in the books—is in full force here. The Silmarillion reads very much like The Iliad, or some of the Old Testament: lots of names, dry historical facts, and battle after battle, with just enough story to keep you going. It's a treasure trove of gems, but they're uncut, and how I wish Tolkien the elder had been able to give them the polish only he could have done.

Words of wisdom for parents—and children—from S. D. Smith, author of the beautiful Green Ember series. (My reviews are here: The Green Ember and The Black Star of Kingston; and here: Ember Falls.)

Your family is the most potent art you'll ever be a part of creating.

(With humble gratitude to our children and their families for art that makes my heart sing.)

Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness by Susannah Cahalan (Simon & Schuster, 2012)

Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness by Susannah Cahalan (Simon & Schuster, 2012)

I enjoy reading medical stories, but they carry a risk: it's all too easy for me to look over my shoulder and imagine the patient's symptoms creeping up on me. It's a good thing that anti-NMDA-receptor autoimmune encephalitis is primarily a young person's disease.

This rare and bizarre condition looks for all the world like a severe psychiatric disorder, but occurs when something provokes a person's immune system to attack his brain. What, why, and how are still unknown, but it's usually curable, if caught and treated—a very expensive process—in time. Susannah Cahalan was the 217th person to be diagnosed with this disease, and if she had not been in the right place at the right time, would probably have been committed to a mental hospital for the rest of her shortened life. If she had had his strength, she could easily have played the part of the Gadareme demoniac.

Thanks mostly to being at a great hospital (NYU), and ending up (after several false starts) with just the right doctors, Cahalan made a full recovery. But while anti-NMDA-receptor autoimmune encephalitis and similar brain disorders are now much more likely to be caught than they were in 2009 when Cahalan fell ill, this is still a cautionary tale of the importance of second (or third or fourth) opinions, and of searching for physical causes for abnormal mental conditions. Autism and schizophrenia are just two of the diagnoses that are sometimes erroneously given to patients with these autoimmune disorders. Unfortunately, the specialized tests needed for proper diagnosis are currently too invasive and too expensive to be used routinely.

Brain on Fire is a gripping, well-written, and important book—even if, once again, I found myself regretting the demise of the censor's blue pencil.