I opened up Facebook this morning to be greeted by the following "Suggested Post."

Some of my readers will immediately recognize the "Castle in Arquenay" as Château de la Motte Henry, where 10 years ago we celebrated Janet's birthday. We chose that fairy tale castle not because Janet is a romantic and highly imaginative person, although she is, but because the château happens to be the home of some dear friends, whose daughter would later be the flower girl in Janet's wedding. They are the most amazing hosts, and the experience was sublime.

The wonderful thing, as Facebook so cheerily told me, is that you, too, can have the Château de la Motte Henry experience! Well, not the friends-and-family perks, but let me tell you, these people know how to host an experience for their paying guests as well! Don't let the price tag put you off—share the cost with friends; it's a huge place! (No, I don't get a commission; I just love sharing something so special.)

If nothing else, take the time to go to the booking site, browse, and dream. Check out the amenities, marvel at the photos. I quote from the overview:

*JUST LISTED AS ONE OF "THE TIMES' TOP 20 CHATEAUX IN FRANCE" FOR HOLIDAY RENTALS!* -- (If you are a group larger than 14, please inquire about additional space & rates.) Live a fairytale dream in this romantic 19th century castle with its own private lake, swimming pool & cinema. Your senses will be dazzled with stunning views, gentle sounds of birds and rippling water, and the rich scents of roses and lavender. You will luxuriate in the privacy of 29 secluded acres, but only travel 2 km to reach all amenities. Whether you are a family, corporate group, or reunion of friends, the château offers pampering, fun and relaxation in a sublime setting for groups both large and small.

The château is an historically listed property, once open to the public, and now privately owned and operated. Featuring a motte (mound) from the time of Henry II surrounded by a moat, spectacular parkland, ancient trees, a private spring-fed fishing lake, and a Renaissance-inspired swimming pool within a secluded walled rose garden, the château is a haven of peace and tranquillity.

Here one can bask in the glorious French countryside, or discover the riches of the surrounding areas of the Loire Valley, Brittany & Normandy from this central location. Children & adults alike will delight in visits to the famous Loire châteaux, Mont St. Michel, D-Day Beaches, the fabulous Puy de Fou theme park and Zoo de la Fleche, all within a 1.5 hour drive. Within 15 minutes drive, one can experience beautiful gardens, golf, riding, nature-activity parks, river cruises, museums, stately homes & more. Or, you may simply never wish to leave the grounds of your very own château...

The château offers extremely spacious bedrooms, all with en-suite bathrooms; reception rooms comfortably yet elegantly renovated in keeping with the romantic style; & wonderful facilities for self-catering, such as a recently renovated designer kitchen with granite and marble-mosaic finishes, as well as three outdoor BBQs.

Special amenities include: Nespresso Machine, Bathrobes, Slippers, Large Welcome Basket, Champagne Reception on Arrival, Toiletry Kits in Bathrooms

Here's another view, Janet's own picture from a decade ago. Can you imagine walking through the woods and suddenly seeing this through a break in the trees?

Facebook is scarily good at surprising me with relevant ads, but this one was the most amazing yet.

Permalink | Read 2431 times | Comments (0)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Computing: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Travels: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I'm working on documentation for our recent cruise to Mexico and Cuba with our neighbors and two of our grandchildren, but it won't be available for a while. In the meantime, you can get everything except our own personal angle by visiting David July's article, The Grateful Talk about the Light at the Mount Sutro website. David's photography and writing are both superlative. I particularly appreciate how well documented his work is, and how observant he is of detail.

Both David and his mom—our neighbor—are excellent photographers who willingly pay the penalty of lugging bulky cameras and equipment while touring. It takes much more than a good camera to make a good photographer, but nonetheless, what a difference the camera makes! Porter, Noah, and I all tried to get a photo of a toucan in a tree. Below is our best effort (Noah's photo) compared with David's. (His photo is from the Mount Sutro Gallery. License agreement here.)

What train transportation could be in America.

Don't I wish! I think trains are the most beautiful and relaxing way to travel. More room and ability to move about than either airplanes or automobiles; tables for working; power outlets; and (if done right) lounge, restaurant, and playspace cars. Human-dimensioned views. Someone else drives. But to compete with planes and cars (especially self-driving cars) a few important potential roadblocks come to mind.

- Good parking at the stations (now often inadequate)

- Cost (currently not competitive in most places)

- Security (if it becomes widespread and popular, would we get TSA-style screening?)

Still, wouldn't you love it?

As if the breathtaking views from Janet's house weren't enough, a very short walk took me through these bucolic scenes of the hay harvest here in the Lucerne area. Large-scale agriculture and huge machines have their place, but I love this more human scale of farming, satisfying to both engineers and lovers of nature.

The Lion of Saint Mark: A Tale of Venice in the 14th Century by G. A. Henty (Preston-Speed, 2000; originally published 1889)

The Lion of Saint Mark: A Tale of Venice in the 14th Century by G. A. Henty (Preston-Speed, 2000; originally published 1889)

When we decided to make a visit to Venice, Porter reviewed the appropriate lectures from our Great Courses Guide to Essential Italy and studied Rick Steves' website and Venice travel guide thoroughly.

Me? I read G. A. Henty's The Lion of St. Mark.

Because Henty's works are primarily about young men and written with an audience of boys in mind, they devote more print to battle scenes than I would prefer; nonetheless I thoroughly enjoyed this adventure novel set in historical Venice. The story was fun, I liked the characters, and the historical setting seems reasonably accurate based on what I learned from our time there. Now that I've actually walked through the setting, I'm re-reading the story and enjoying it even more.

Henty's books have been republished, and I had a hardcover copy to read. But The Lion of St. Mark is also available as a free Kindle book.

We visited so many churches in Venice (Italy, not Florida), and each one had to be seen twice: first as a museum, because everywhere you turn there's a famous work of art, and then as a church. From the art to the architecture to the acoustics, each of these ancient, monumental buildings is a soul-expanding experience.

The Frari Church affected me the most. It's stunningly beautiful, with glorious arches and windows and columns, and famous artwork everywhere. Titian worshipped here! And here is he buried, as is Monteverdi, and Canova's heart. (Canova is spread around a bit.) Titian's Assumption of the Virgin is the high altarpiece.

But it was a side chapel that captured me. It was open for private prayer, so I walked in and knelt, alone. I have no idea how much time I spent there, but it was long enough to gain an unsought appreciation for the value of icons, and pictures, and other physical representations of people and events—so important for conveying information in times when the written word meant nothing to most people. It was not information that was given to me, however, but an environment conducive to meditation, thought, and listening. It's easy to talk too much when I pray, as if I expect the experience to be a one-sided conversation. This was something entirely different, and when I stepped out of the chapel and walked back into the nave it was as if I had been altogether elsewhere—I mentally tripped over a threshold. I'm sure I was gone only a few minutes, but the feeling of time suspended was intense.

Swiss yards tend to be small because land is precious and the population is dense. Even so, they come up with some very clever and often beautiful ways of not mowing lawns. Here are some of the creative yards I've found within a short walk of Janet's house. (Click to enlarge)

Cascades of beauty.

'Way back in the early 1980's, our little city of Altamonte Springs pioneered a program of reclaiming treated wastewater for irrigation. Now we're capturing stormwater runoff from Interstate 4 and reclaiming that, instead of collecting it in retention ponds. I love our city. "Progressive" is not always a positive term, but in the case of Altamonte Springs it means some great innovations.

Here's the most recent: the city is partnering with Uber to offer discounts on rides within the city, and greater discounts from anywhere in the city to the SunRail train station. It is the first city in America to do so.

I've said for years that Altamonte Springs needs a good public transit system, but couldn't figure out a way to make it work with our sprawling subdivisions. There are two bus stops just outside our neighborhood, but it takes me 30 minutes to walk there—very difficult with luggage (when I take the bus to the airport) and impossible for less able folks. Taxis are expensive and in my experience take an unacceptably long time to arrive. They're not really interested in short hops, which covers just about any ride from one part of Altamonte Springs to another.

I had envisioned some sort of on-demand mini-bus system that would provide transportation from neighborhoods to the city's major attractions, but did not see how it could possibly be affordable. Later, several local cities did try to create such a program with Lynx, the Orlando area's existing bus system, but it fell through. Lynx rejected the idea as too costly.

Then along came Uber.

I'll be the first to confess that Uber, like Airbnb, makes me nervous. Good Democrat that I am, I harbor an innate belief that governmental regulation means better safety. This creates conflict with my Inner Libertarian, who knows that to be false, my Inner Republican, who thinks private industry can usually do a better job, and my Inner Distributist, who trusts small, individual capitalists and worries about large, corporate ones. Many of our friends speak highly of their Uber experiences, and Altamonte Springs has just propelled me into their camp, though I've yet to take my first ride.

Now if only the people who run SunRail had half as much sense as Altamonte Springs, and offered service to the airport!

Toubab.

White person.

I'm told it's not a racial slur, but have my doubts. It felt like one. It was certainly a verbal assault.

Toubab, toubab, toubab! Give me candy ("minties"), give me pencils, give me money, buy my product, what do you have for me?

Everywhere we went we were assaulted by this cry, from children and adults, but especially from the children. I'm told it's much, much worse in the main tourist areas—which we avoided—where hustling is a major adult occupation, but it was saddest to see in the children. Even toddlers came up to us with their hands out, calling "Bab!"

Before we left home, we were advised from many sources to bring a supply of items to give to the children. Some recommended candy, others pencils or pens. Well, why not? It's a trivial expense for us, and so joyfully received by the kids. Why not give them a little happiness?

Fortunately, Kathy warned us in time to halt that apparently generous impulse. The lesser of the consequences is what it does to white people living in the Gambia. Because begging is so successful with tourists, who are generally white, local whites cannot go about their everyday lives without being bombarded by swarms of pint-sized mendicants. It feels painfully rude to pointedly ignore people, especially children, but it's the best defense.

The worst consequence, however, is what the practice does to the Gambians. From the time they learn to walk, these children are being taught that the way to acquire anything is to beg for it. This mendicant culture does not leave them as they grow, though it morphs into a more sophisticated form: the country is completely dependent on foreign aid, NGOs, grants, and donations from overseas.

Nor does it help when the donors are no more careful about their gifts than tourists thoughtlessly tossing candy to a crowd of children. While we were there we saw boxes piled on boxes, just sitting in a storeroom—as they had been for over a year—labelled "Books for Africa." No doubt the American donors are content as they imagine happy children poring over their books, and maybe, someday, in "Gambian Maybe Time,"* they will—if the volumes don't rot away in storage first. Bureaucratic nightmares, graft, and outright fraud prevent a lot of well-intentioned assistance from reaching those who need it. Kathy told us of one organization in Germany that persists in pouring money into a local group despite having been shown clear evidence that it is nothing but a scam.

Need in the Gambia is great. Unemployment is very high, and long before Syrian refugees made the headlines, young Gambian men were taking the "back door" route to Europe (illegal entry), which many still see as their best hope. But if the Gambia itself is to have hope, they need to shed the mendicant mentality. For now, they do need aid from outside, but if that aid isn't aimed at putting itself out of business, it does more harm than good.

Without the wisdom of the serpent, the dove isn't so harmless after all.

Despite many serious problems, the Gambia is making progress, and there are places where money can make a big difference. Education, for example, and the simple act of helping a family with their children's school fees. But even that is a painfully slow process with some backward steps along the way. The government has made education a priority, and indeed there are now many more schools available. Unfortunately, the creation of new school buildings vastly outstripped the availability of competent teachers for staffing them. More children than ever are going to school, but without decent teachers, many are simply wasting their childhoods (and their parents' or sponsors' money) sitting in classrooms. That's one reason help with school fees is a good investment; many private schools, though far from all of them of course, still provide a good education. That is why you will often see see Muslim children at Catholic schools, with their families' blessing: since Muslims and Christians generally get along well in the Gambia, parents who value education don't hesitate to take advantage of good schools whenever they can.

To return this post to the experience of being the only white folks in a sea of people whose skin has a deep and rich darkness almost never seen among American blacks—it wasn't nearly as surreal as you might think. After all, I don't usually see my own face. It was when I looked at Porter and Kathy that I was startled by the contrast. If it hadn't been for those never-ending cries of "toubab!" I might have been able to forget what I looked like.

*The Gambia's time zone is Greenwich Mean Time, but the wry observation that GMT stands for "Gambian Maybe Time" is not without basis in fact.

Before the wheels of our first flight had left the ground, at least five people had, separately and individually, encouraged me to "enjoy the adventure." This became my motto throughout the trip, helping me glide through moments where I amazed Porter with my relaxed lack-of-panic. I really did enjoy almost every part of the adventure, all the more so looking backwards and knowing that so many things that could have gone wrong, did not. It was all in all an amazing two weeks, and when people ask if we will return, the reason for replying, "not anytime soon" is not due to negative experiences, but that there are so many other places we want to see.

I will, however, admit that the largest factor in making the trip both awesome and not scary was having a friend on the ground (Kathy, with several years of local experience) and a caring, competent guide/guardian angel (Kathy's student and friend, B). From New Zealand to Japan, Switzerland, France, and now the Gambia, my taste in overseas travel has always favored the local over the standard tourist experience.

Thursday, January 14 - Friday, January 15 Our first day of travel was actually our first two. We left Orlando at a comfortable time, shortly after noon, and arrived in Banjul around six the next evening. Porter had done a lot of research into flights from here to the Gambia, including options that had us going via Tenerife and Casablanca. That would have been interesting, but I'm glad we ended up with a much shorter trip on an airline less renowned for losing luggage.

First stop: Newark. We've flown through Newark a lot, but United's international gate area was something new indeed, and made for a very pleasant wait. Every airport I've flown out of has some sort of seating at the gate. Good airports have electrical outlets available, but never enough. Many times I've seen pleasant seats going unused at a crowded gate, while weary travellers sat awkwardly on the floor next to the few existing electrical outlets, all of which were positioned to favor the cleaning crews' vacuums over travellers' electronic devices. The better airports have charging stations, or power outlets available in some seats, but again, never enough.

First stop: Newark. We've flown through Newark a lot, but United's international gate area was something new indeed, and made for a very pleasant wait. Every airport I've flown out of has some sort of seating at the gate. Good airports have electrical outlets available, but never enough. Many times I've seen pleasant seats going unused at a crowded gate, while weary travellers sat awkwardly on the floor next to the few existing electrical outlets, all of which were positioned to favor the cleaning crews' vacuums over travellers' electronic devices. The better airports have charging stations, or power outlets available in some seats, but again, never enough.

United Airlines in Newark had enough. In addition to power outlets and desk space, each station was equipped with a tablet from which one could use the Internet, play games, shop at various airport stores, and order food. I call that a great idea, though I didn't sit down for long. I left Porter at work at our desk, watching over my charging phone, while I did laps around the gate area, logging my customary 10,000 steps for the day. I would accomplish that goal only three more times before returning home. Contrary to all my expectations, we sat a great deal more than we walked in the Gambia.

Travelling long distances with small children is challenging at best, and when the airline has lost your stroller and the Customs officials are being particularly nasty it can be a nightmare. Travelling alone means there is no one to watch your belongings when you want to duck into the restroom or pick up a bite to eat along the way. (The fancy new setup at the airport gates can take care of the latter problem, but not the former.) But long flights with several stops can be enjoyable and even restful if you're travelling with a pleasant, adult companion and plenty of entertainment in the form of Kindle books and World of Puzzles magazines. Time changes have also become a lot easier to deal with since I've learned to sleep on the plane when I'm tired and not pay attention to the clock when I'm not. (It also helps to arrive at one's destination in the evening rather than in the morning.) All that to say, as long as the flights are more or less punctual and I have plenty of time to make connections, I enjoy air travel.

Travelling long distances with small children is challenging at best, and when the airline has lost your stroller and the Customs officials are being particularly nasty it can be a nightmare. Travelling alone means there is no one to watch your belongings when you want to duck into the restroom or pick up a bite to eat along the way. (The fancy new setup at the airport gates can take care of the latter problem, but not the former.) But long flights with several stops can be enjoyable and even restful if you're travelling with a pleasant, adult companion and plenty of entertainment in the form of Kindle books and World of Puzzles magazines. Time changes have also become a lot easier to deal with since I've learned to sleep on the plane when I'm tired and not pay attention to the clock when I'm not. (It also helps to arrive at one's destination in the evening rather than in the morning.) All that to say, as long as the flights are more or less punctual and I have plenty of time to make connections, I enjoy air travel.

On this trip I added three new countries to my collection in a single day. By the time we landed in Brussels it was Friday. (Technically, I didn't actually enter Belgium until our return trip, as we didn't have to go through Passport Control to catch our next flight.) This cute recycling station is the only photo worth sharing I have from our stay in Belgium.

On this trip I added three new countries to my collection in a single day. By the time we landed in Brussels it was Friday. (Technically, I didn't actually enter Belgium until our return trip, as we didn't have to go through Passport Control to catch our next flight.) This cute recycling station is the only photo worth sharing I have from our stay in Belgium.

Our Brussels Airlines flight to Senegal, however, provided this example of an intelligent seat console, complete with cup holder and USB charging port. As usual, there wasn't much attractive to me in the entertainment offerings, but I did enjoy watching The Martian for the second time. It was especially enjoyable having read the book since my first viewing of the film. Porter also took the opportunity to watch Bridge of Spies, which he thought was great.

We didn't officially enter Senegal on this day, either, as we did not change planes. We waited there for over an hour, however, and I was allowed to get to the very edge of the door to snap this photo.

We didn't officially enter Senegal on this day, either, as we did not change planes. We waited there for over an hour, however, and I was allowed to get to the very edge of the door to snap this photo.

The flight from Dakar to Banjul is short; we probably spent less time in the air than we did getting out of the airport once we landed. Our first impression of the Gambia was not the most pleasant: long waits, and people pushing and shoving and hustling. What must the Swiss think? The Swiss know how to wait a few steps back from the luggage carousel, so that everyone can see, approaching the belt only when it's time to pick up their own bags.

This was also the only time our luggage has been x-rayed on the way out of the airport.

We were glad to be able to tell the hustlers that we had no money; Kathy had dalasis for us, but she was out of reach on the other side of the border controls. At least we certainly hoped so, though she was out of sight as well. We learned later that the hustlers would have been happy to take our dollars, but we weren't inclined to want help with our luggage, anyway.

Finally we made it through, and there was Kathy—and how great it was to see her again! And to meet B., whom we knew only by name and voice: he had recorded the numbers from 1 to 100 in the Mandinka language for our number-and-language loving grandson, Joseph. Apparently B. felt the connection, too, as one of the first things he asked us was to tell him more about Joseph.

B. had arranged a car to transport us all to Brikama, where Kathy lives. The trip began a bit inauspiciously, as in order to start the engine the driver resorted to a trick I remember seeing as a young child: getting several men—including Porter—to push the car to a certain speed, then popping the car into gear. After a couple of tries, it worked, and we were on our way.

Google says it's a 20-minute ride. There's a lot Google doesn't know.

The car started giving trouble. It stalled. They were able to get it started again, by the same method. It stalled again. The driver decided something serious was wrong, and put into effect the Gambian equivalent of calling AAA: he hitched a ride back to the town we had just passed through and found someone else with a car, who took us to our destination and then returned to help out the first driver.

It was while we were waiting for the second car—in the rapidly-falling darkness of a land near the equator, on an isolated stretch of the highway with no street lights, in a completely foreign third-world country—that Porter wondered why I was so calm. Well, why not? Kathy wasn't upset, B. wasn't upset, and the driver was only upset with the person who had borrowed his car and apparently treated it badly. If the people who knew the country found nothing of special concern in the situation, well then, it was just part of "living the adventure."

Finally, we arrived at Kathy's place. We were more exhausted than hungry, but B.'s mother had send us dinner, and he joined us for the meal. We weren't too tired to enjoy both our first Gambian meal and the conversation.

But thus it came about that practically the first thing we did upon arrival in the Gambia was to break the rules our doctor—and all the travel advice sites, including the CDC's—gave us about what not to eat there: Be sure to avoid everything—except for fruit that you peel with your own hands—that has not been thoroughly cooked.

It was a problem that we would face throughout the trip: how to balance our health and safety concerns with the need to be courteous to our hosts. We felt that in this case the choice was clear, so we dug right in to a dish that included fresh tomatoes and lettuce. It was just another part of the adventure. And although we didn't know for sure until the next day, I'll close by revealing the punch line.

We did just fine.

There was evening, and there was morning: the first day. And it was very good.

I've been overseas every year for the past decade, so it ought to be routine by now. But travelling to the Gambia is not like travelling to Japan or to Switzerland. For starters, we needed visas.

Most visitors to the Gambia don't need visas, but the United States is special. American tourists are required to fill out a bunch of paperwork and fork over $100 (each). Because we have family overseas, we are always a bit nervous when our passports are out of our hands, but the process went smoothly and we had them back, with the necessary visas, in just a few days.

.jpg) Then there was the medical side. Immunizations (yellow fever, typhoid, meningococcal, hepatitis A & B) and medications (malarone to be taken daily as an anti-malarial, Cipro in case of traveller's diarrhea, probiotics in case we had to use the Cipro) cost us some $1200. We were spared the rabies vaccine, although if the doctor had known how many stray dogs we were to encounter, the story might have been different. Our insurance company believes in funding preventive medicine, they say, but clearly their idea of tropical disease prevention is encouraging people to stay home.

Then there was the medical side. Immunizations (yellow fever, typhoid, meningococcal, hepatitis A & B) and medications (malarone to be taken daily as an anti-malarial, Cipro in case of traveller's diarrhea, probiotics in case we had to use the Cipro) cost us some $1200. We were spared the rabies vaccine, although if the doctor had known how many stray dogs we were to encounter, the story might have been different. Our insurance company believes in funding preventive medicine, they say, but clearly their idea of tropical disease prevention is encouraging people to stay home.

And finally, the new wardrobe. As nearly all of you know, I'm not a shopper, I don't care anything about clothes as long as they are comfortable, and the occasions for which I will put on a dress or a skirt are so rare as to be barely perceptible. (Weddings of family members. That's about it.) But then Kathy happened to mention—fortunately, in time for us to do something about the problem—that I'd need to wear a skirt or dress (mid-calf or longer) whenever we went out in public, and even at home if we had visitors.

I suppose most women would have just packed a few dresses and been fine. I needed to go shopping (oh, joy) and climb over a major psychological barrier. Dresses, after all, are the tools and symbols of oppression. Oppression of women by men, of children by parents, of students by teachers. Unless you happen to be the queen, or to live in Scotland, skirts are not associated with power.

While I might not be as sensitive as some in my family to shirt tags and wrinkles in my socks, it's still an issue for me, and I still remember, and not happily, the time when as a very young child I was required to wear a certain dress—beautiful, and hand-made with lots of love, but very scratchy—for an interminable period. Really, it was just long enough to go to the photographer's for a professional picture, but it was torture to me. I'm grateful that most of the time my mother was more merciful when it came to my clothes, but dresses = discomfort was ingrained in me from an early age.

And then there was school. As if school weren't oppressive enough all by itself, in those days all girls were required to wear dresses or skirts and blouses. Even on the playground, even in gym class. Girl Scout uniforms were dresses. Church clothes were dresses. Believe me, if it had been possible for me to get used to wearing skirts, I had plenty of opportunity to do so. It didn't happen.

On top of that, dresses in those days were not loose and flowy, but short and tight. It was the era of the miniskirt; even for the more conservative among us hemlines had to be above the knee, greatly limiting movement and action. A dress was a prison. But the times, they were a-changin.' When I went off to college I left my dresses behind me, and after graduation being a computer programmer allowed me to land a job without much in the way of a dress code. I'm not certain, but I think the next time I wore a skirt was at the rehearsal dinner before our wedding.

Hence my psychological shock at Kathy's statement. Oh, tourists can get away with anything for the sake of their euros, and students sometimes wear jeans and t-shirts, and the rules in that patriarchal society are much looser for men—though Porter still could not wear shorts despite being just 13.5 degrees away from the equator. But mature women do not show their legs in the Gambia. Not if they want to be respected. Kathy quite rightly did not want her American friends to embarrass her Gambian friends. We probably did, anyway, because Gambian women dress beautifully at all times, and even the men have a keen sense of style. But at least we weren't immodest. (Incidentally, Gambians have a much healthier attitude toward public breastfeeding than Americans; it's legs that have to stay covered.)

_WPW_GM_Fajara_Kathy, Linda walking along Kairaba Avenue.jpg) Nothing about the experience was as bad as the anticipation. The shopping was the worst, but Kohl's and Target (both online) came through with three acceptable skirts at reasonable prices. They were even comfortable, as skirts go, because they were soft and loose and long. I ended up only bringing two with me, not wanting to take the time to do necessary hemming on the last one, but why should I need more than two? We wouldn't be going out in public that much, would we? (Well, yes, we would. But two skirts were still sufficient.)

Nothing about the experience was as bad as the anticipation. The shopping was the worst, but Kohl's and Target (both online) came through with three acceptable skirts at reasonable prices. They were even comfortable, as skirts go, because they were soft and loose and long. I ended up only bringing two with me, not wanting to take the time to do necessary hemming on the last one, but why should I need more than two? We wouldn't be going out in public that much, would we? (Well, yes, we would. But two skirts were still sufficient.)

My sister-in-law made an odd but brilliant suggestion, in the form of mid-thigh underwear from the Vermont Country Store. I was skeptical, and indeed they did not suit me as underwear. But as something to wear under my skirt and over my usual underwear, they were perfect for the Gambian weather situation: temperatures in the 90's and no air conditioning. The over-underwear did a wonderful job of absorbing the sweat that otherwise poured uncomfortably down my legs. (As a Floridian, I'm accustomed to hot weather, but deal with it by [1] wearing shorts, and [2] relying on air conditioning.) There's also no overestimating the psychological value: they felt like shorts on my body, which helped undo some of the mental discomfort. I had one other trick up my sleeve as well: When I caught myself feeling overpowered and bowed down because I was wearing a skirt, I imagined being a Scottish chieftain, and that actually worked—even though my skirt could hardly have looked less like a kilt.

We were out in public a lot. As Kathy explained, the Gambia is a hard place to be an introvert. Although I would usually rip my skirt off in favor of shorts as soon as we walked in the door of her house—in order to cool down a little—for most of our two weeks in the Gambia, I lived in a skirt.

And we developed an uneasy friendship, the skirts and I. After returning home, I washed them and put them away in the back of our closet, so glad, as they say, to see the back of them. But one day, after sufficient time has passed, I will pull them out again and wear them for some occasion, perhaps a party. I'm glad to have them in my arsenal of clothing. Being loose, long, and of soft material they are a far cry from the dresses of my childhood. Besides, they are full of wonderful memories!

As for the rest of our trip preparations, I suppose they were mostly normal. We had our tickets, our visas, our "yellow cards" showing yellow fever immunizations, our anti-malarial meds, the proper clothing, and a few gifts. It was time to begin the adventure!

I know people who are fond of saying, as if it were original with them and somehow encouraging to others, that we should never ask for what we deserve, because what we all deserve is Hell. As unhelpful as this aphorism is, there are times when everyday life points to a kernel of truth there. We remember vividly the times when we've done something stupid and paid the price, or done something stupid and managed somehow to escape disaster, but we may not even be aware of how many, many times we've been equally stupid, or more so, and escaped scot free. How often have we taken a foolish chance while driving, or set a can of soda near the computer, or carried a large stack of breakable objects? How many times have we thought, "I knew that was going to happen" when a foolish risk has ended badly? Truly, when we know what we should do and act otherwise, do we deserve to escape the consequences? No—but surprising often, grace abounds anyway.

It's an old, sad story, and out of respect for those who, like me, are not fond of suspense, I'll say up front that this one has a happy ending.

I'm usually a bit compulsive when it comes to doing backups. I have general backups, and specific backups. Whole and incremental backups. Backups divided over several years and different external drives. But I'm not perfect about it, and this was one of those times.

Mostly I find a once-a-week backup sufficient for my needs, but recently I've been working pedal-to-the-metal on processing our photos and videos from the Gambia, so I got into the habit of backing up my work every night. See, I know the right thing to do! But one night the backup system gave me trouble. Instead of spending the next day sorting it out, I carried on feverishly with my work. I was making such good progress! Who could be bothered with a problem that was, I knew, going to be frustrating and time-consuming to sort out? So for a few days—highly productive days—that nightly backup didn't happen.

I'm a big fan of the recycle bin. I love that a deleted file doesn't really disappear right away, so that accidents and mistakes are reversible. However, some files, such as video files, are too big for such treatment. For those I use the shift-delete function, which bypasses the recycle bin and erases the file directly.

One morning I was working with a number of video files, and got a little too careless with my quick response to the "Are you sure you want to permanently delete this file?" question. I was certain I had highlighted the video I was done with, but Windows Explorer had other ideas. You want to delete the entire directory? The entire directory with your final processed photos? The directory that represents 60+ hours' worth of work? Fine, no problem, I can do that for you in under a second.

I stared at the computer. I didn't believe what appeared to have happened. I turned my computer inside out, searched from top to bottom. Finally I let myself admit that the files were gone. Completely. Gone.

I was surprisingly calm. Sometimes big events leave you too overwhelmed to be upset. Besides, I did have some backups, though they were, as I said, a few days old, and the most recent one had been corrupted by the above-mentioned problem. But as I also said, I'm usually compulsive about backups, and if I didn't have my work in final form, I did have it in next-to-final form, and the form before that, and the form before that. What had been done once could be done again, and though the magnitude of effort lost was mind-boggling, I took comfort in a comment reader-friend Eric once made here about work being done better the second time around.

As it turned out, we'll never know how much better I would have done the second time, and that's more than fine with me.

When files are deleted from a drive, even by shift-delete, they're not really erased. They're no longer visible to the user, but the data's there until it's overwritten. I knew that, but had no idea how to take advantage of it. Then a little Internet research led me to a data-recovery program called Recuva.

Had my files been on the C drive, I may have been in trouble, because I did quite a bit of work before finding that program, and the more time that elapses, the more likely the data is to be overwritten. But because of space considerations, my data was on an external drive that I had been careful not to write to since the loss. The operating system, or some other program not under my control, probably did something, but—to shorten the story—with the help of Recuva I was able to recover all but about half a dozen files. The few that had been damaged I easily recreated from the next-to-final layer. I'm very grateful I did not accidentally delete a higher-level directory!

Curious as to what an overwritten file looks like? Here are an original and its corrupted version. You can still see some of the basic structure. (Click to enlarge.)

Once I had the program downloaded and unzipped to a flash drive, using Recuva to restore the files was quick and easy. The long and tedious part of the job came in checking the integrity of the recovered files, but that only took five or six hours, and by the next day I was back to where I'd been 24 hours earlier.

With one important exception: I now have Recuva on that flash drive, available should I need it again. It's especially important to have it handy in case I ever need to recover files from the C drive, where overwriting can happen quickly. Which I sincerely hope never happens!

It's amazing how easy it is to accept the loss of a day's work—which normally would have had me tearing my hair—when faced with the realization that the loss could have been many times greater.

Truly, grace abounds.

Permalink | Read 2637 times | Comments (3)

Category Computing: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Travels: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] The Gambia: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I'm sorting through the photos from our Gambia trip. During our safari in the Fathala Game Reserve in Senegal, I hastily wrote down the names of the animals so that I could properly identify the pictures. That is, I wrote down what I thought I heard our guide say. Her English was excellent but heavily-accented, and I knew that what I heard could not possibly be right. But I wrote it as I heard it, counting on the Internet to help me after we returned home.

It did. For those of you who are curious,

"Rowland antelope" = roan antelope

"yellowbill asparagus" = yellow-billed oxpecker. I knew it couldn't be "asparagus," but that was the closest I could come.

"red vervet monkey" = "patas monkey." I am certain I heard "red vervet monkey," but I couldn't find any red vervet monkeys by name, although many images showed them as a brownish-red color, even though they are apparently often called green monkeys. Google also suggested red velvet cake, which didn't help. Then I found this Wikipedia article, which suggests this of the patas monkey (which looks very much like what we saw):

The patas monkey (Erythrocebus patas) ... is a ground-dwelling monkey distributed over semi-arid areas of West Africa, and into East Africa. It is the only species classified in the genus Erythrocebus. Recent phylogenetic evidence indicates that it is the closest relative of the vervet monkey (Chlorocebus aethiops), suggesting nomenclatural revision.

So I'm sticking with the name our African guides gave it.

Here are a couple from other parts of our stay:

"nests vled vivas yellow female" = some sort of weaver birds' nests, possibly village weaver, possibly Vieillot's weaver. This was a tough one, from our Janjanbureh trip. Fortunately, birding in the Gambia is a popular tourist activity, so that helped. Which particular weaver "vled" is supposed to represent, I can't guess.

"never die plant heal wound kill snake" = moringa plant. This was tougher than it should have been, because where I saw it, the plant had other plants growing with it, and its own leaves had been mostly stripped off. But finally I'm convinced that this is it, despite there being no mention online to confirm our host's contention that it kills, or even repels, snakes.

The rest I actually heard correctly, though I didn't write down as much as I would have liked to. "Write down" meant changing the file name of the camera image to include the label, not the easiest of ways to take notes, but it's what I had.

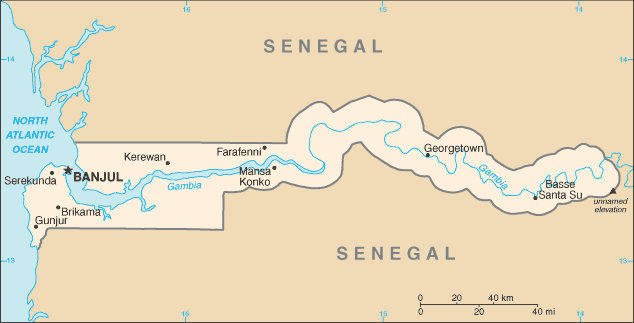

Many of you know that we recently returned from a two-week trip to the Gambia, that tiny country within Senegal in West Africa. Since I never fully appreciate an experience until I've written about it, I've started a new category here, in which I'll put both travel memories and Gambia-inspired musings. Expect it to be rather random; if I wait to get it all organized I'll have forgotten too much. (Lots of thinking to do, many activities, and over 1600 photos.) In the meantime, here's some background.

After a couple of false starts some 45 years ago, I finally found a college roommate who became a friend for life. (Realize that in those dark ages, even smokers and non-smokers were often paired up to live together!) Kathy went on to get a Ph.D. in mathematics and enjoy a long career as a university professor with a well-deserved reputation as an excellent and caring teacher. Several years ago she embarked on a different sort of adventure altogether, and is now a math professor (and department chair) at the University of the Gambia, with an even stronger reputation for both excellence and caring. She's not there for the adventure (although there is plenty of that), nor for the salary (meagre), and certainly not for the working conditions, but to make a difference in the world. Yes, she's a saint, a fact of which I'm all the more convinced since our visit. (You can ignore this part, Kathy, assuming your flaky Internet connection lets you see it. You and I both know you're still the crazy person I knew back in college.) Perhaps it's more useful—since labelling people as saints tends to put them out of reach—to say that she's a Christian called by God to use her skills and experience in an unusual place. However you look at it, she's there, and is making a difference. The world, Africa, the Gambia, even the University—these are too large to exhibit visible change. But without a doubt she has for a number of years been changing the lives of families and individuals for the better.

However, despite the University's state of denial, she won't be in the Gambia forever. Hence our determination to seize the year (and the presence of this trip on my 95 by 65 list). The only reasonable time to make the trip was in January, which is during the dry season and between semesters for Kathy. Coming during the dry season turns out to be very, very important: the weather, though still hot (90's) is much more pleasant, the mosquitos are much less numerous, and transportation tends to be through a few inches of dust instead of a foot or more of garbage-and-water. Definitely the time to go!

So we went.

Some people travel for adventure. Others for the educational and cultural growth. As much as I value the latter, the primary importance of travel for me is still being with family and friends—and specifically, seeing them in their native habitat, as it were, so that their stories and experiences have more meaning when I hear them from far away. The educational experiences are a great bonus thrown in, and on this trip we even had a few adventures.

Stay tuned.

I wrote this in response to someone's Facebook discussion, and put too much time into it not to save it here. The subject was the very survival of America, and one optimist had said, "Doom and gloom speak just because the candidates of your choice aren't winning. People have been saying for over 200 years that the country is doomed if so and so gets elected to office. Well the country is still here and alive and well." This was my response:

It is true that of the presidents I have experienced, the ones I thought were good people (Carter, Bush II) turned out to be terrible presidents, and the ones I thought were nuts (Reagan, Clinton) turned out much better than I could have imagined. Sometimes good intentions aren't enough, and sometimes people rise to the office. And good and bad luck have more effect than we admit.

Our recent trip to the Gambia convinced me that the best equipment in the world will not survive ignorance, abuse, and lack of regular maintenance. I worry not only for the United States, but for all of Western Civilization. It is under attack from all sides, from the Terrorists Formerly Known as ISIS to American college campuses. We whose mighty heritage this is have not done well in keeping it clean and oiled. Instead of fixing the broken parts, we trash them. Our children have no idea how to keep this great gift of the ages in working order. The beliefs that massive debt (personal and national) is okay; that name-calling is rational discourse; that our own failures are actually someone else's fault; that success implies not hard work but ill-gotten gains; that poor, even immoral, choices should not have consequences; that those who disagree with us are somehow subhuman and deserve whatever we can heap upon them—these attitudes, much more than whoever gains the highest office, are what will bring us down.

Sure, there are still pockets of resistance, but they're getting smaller and weaker. There's still hope—but only, I think, if we realize, as the great Pogo once said, "We have met the enemy and he is us."