I'll admit I'm astonished that Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.'s shocking book, The Real Anthony Fauci: Bill Gates, Big Pharma, and the Global War on Democracy and Public Health has not generated more interest, especially since at the time I first wrote about it, the Kindle version was only $3. It's $15 now, and the hardcover close to $20, but I'd say it's still worth it at that price, especially if you can't get it from your local library. Or you can do what I do: put it on a watch list at eReaderIQ; for a brief time yesterday it was only 99 cents. At that price I would have bought copies for a few friends—if I hadn't been away from home for the whole day. I find the eReaderIQ service worth supporting, by the way: it really helps with playing Amazon's little games.

I understand that people might be skeptical, whether, as in my case, from distrust of the Kennedys in general, or from a reluctance to question authority—especially when questioning authority can get you shoved into a "right-wing extremist conspiracy theorist" bucket. If you have the courage to look around outside of your comfort zone, however, I predict you will find this book worth your while.

Here are two short (about 5 minute) videos from my current favorite Left Coast liberal academic scientists, whose genuinely liberal credentials I don't doubt, albeit they also sometimes find themselves flung into the above-mentioned bucket when their search for truth leads them in certain directions. Both videos contain Bret's and Heather's evaluations of the book, and more importantly, their evaluation of its documentation. The videos do well at double speed if you want to save time. Spoiler alert: Bret and Heather are even more concerned than I am, with better reason and authority.

This one is just over five and a half minutes long.

As I said in my review of the book, if what Kennedy claims, with such extensive documentation, is true, why are Dr. Fauci and a whole lot of other people not in jail? If it's not true, why isn't Fauci suing Kennedy for libel? I expected outrage on all sides, refutation, corroboration, investigation.

I did not expect ... silence. That silence on the part of investigative journalists, academic researchers, and medical professionals almost scares me more than the book.

I understand that people's lives are too busy for them to want to tackle a long, dense non-fiction book, so I don't urge you lightly to read The Real Anthony Fauci. But for your own health, and especially for your children, if you can make time to read this book, or listen to it in audiobook format, it has my strongest recommendation. The story is as riveting as it is frightening, and I was surprised at how quickly I finished it. I do recommend the Kindle version; the primary reason I also bought the hardcover was the knowledge that Amazon can make a Kindle book "disappear" at any moment, even from my physical e-reader. Most of the time I'm more comfortable with physical books, but in this case I actually find the digital version friendlier to the eyes. Don't be put off by the fact that the e-book format appears to double the page count (934 vs. 480).

Those who know me know that I do not like horror stories. Even during my Girl Scout days I was not a fan of ghost stories around the campfire. The Real Anthony Fauci is a horror story par excellence, because most of the others are about situations we are very unlikely to experience, and this one has already happened to us—we just didn't recognize it. Nonetheless, I am, as Bret suggests, hopeful: Information is power, and this book has answered questions that have troubled me for decades.

Permalink | Read 1330 times | Comments (0)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

What do you think explains the current political climate?

- Half the country is made up of f-ing idiots.

- The elections were stolen.

- People are helpless sheep, easily manipulated by dangerous, dark forces.

- All of the above.

Sorry, all of those answers are unacceptable, no matter how tempting they might be.

Even if they were 100% true, none of them would be an answer we can work with.

Suppose you are right in your take on the issues. Half the country see them differently. You're not really so egotistical as to believe them all to be less intelligent, less educated, and less wise than you, let alone less kind, generous, thoughtful, and loving. There are reasons these people believe the way they do. It's important to understand them.

Suppose any given election was won by nefarious means, cheating, gaming the system, or error? Some of them have been, guaranteed. And it's nothing new; what's novel is that the effects are so nationally important. Our COVID response ushered in radical changes to our voting system, and faith in its integrity is understandably very low. It will take everyone on board to restore that; we must get beyond the elementary school playground level of "I lost, therefore you cheated" and "I won, therefore the elections were fair."

Are we being manipulated by outside forces? By conspiracies, cabals, demons, extraterrestrial aliens, or self-important elites with unprecedented wealth and power? I'm inclined to think the chances are well above zero. But mostly I think we are just too busy, too tired, and too stressed to be able to resist the currents that push us.

I believe our only hope is to think small. We can't fix the world. But we can be good neighbors.

Get to know people whose opinions you despise. Work with them. Eat with them. Find something in common that you like to do and do it together. Serve together for a common cause.

In being good neighbors, we might learn how to take the next step.

Being a household of two, we can't keep bread goods out on the counter as we once did; all too often they spoil before we can finish them. Thus, when I bring them home from the grocery store, they often go directly into the freezer, to be thawed as needed.

Being a household of two, we can't keep bread goods out on the counter as we once did; all too often they spoil before we can finish them. Thus, when I bring them home from the grocery store, they often go directly into the freezer, to be thawed as needed.

That's a mistake, I've discovered. The directly part, I mean. Perhaps you've known this trick all along, but if it's new to me, it's undoubtedly new to someone else, so worth publishing.

Now when I come home with bagels, or English muffins, or anything else I might want to use by parts, I divide them before putting them in the freezer. It's only a matter of seconds to cut a bagel in half, but what a difference it makes when I want to have one for breakfast, if it comes from the freezer pre-sliced. I can take just a half if I want (when did bagels get so big, anyway?), or pop two halves directly into the toaster instead of waiting for them to thaw enough to be sliced. Even bagels that come (mosty) presliced in the package can benefit from this treatment, as I find they're inclined to stick together too much without it.

This is a great convenience, and if there's a down side I haven't yet encountered it. Perhaps the additional exposed surface is more prone to drying out, but I've not yet had the problem.

YouTube is not exactly reliable when it comes to recommending videos for me to watch, but look what showed up in my sidebar tonight:

As most of my readers know, I'm a huge fan of J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings books, but not of the movies for a number of reasons. Even though I feel the film story line and characterization are a betrayal of the spirit Tolkien put into his world, I can't deny that there are parts of the movies that are excellent, from the New Zealand setting to the music, and of course I adore this version.

Permalink | Read 870 times | Comments (1)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Music: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The big news is—there is no big news.

Nicole, now a tropical depression, is marching through Georgia rather more peacefully than General Sherman did. It slipped by to the west of us, and although we were theoretically in its grip for much of yesterday, it might have been an unnamed, minor storm, or possibly the effects of a hurricane passing far off at sea. The rains gradually diminished as the day progressed, and only an occasional gust of wind reminded us that something meteorological was going on.

We even went out for lunch in the middle of it all, and noticed only a slight diminution in traffic, although some places were still closed. Not too surprisingly, these were mostly government, church, and medical facilities, institutions not known for being able to turn around on a dime and say, "Okay, it's all good, let's re-open."

There is still risk of flooding, as runoff from already-saturated ground fills already-flooded rivers, but in our own neighborhood we travelled on dry ground the roads that had been so devastatingly flooded by Hurricane Ian.

Were this a century ago, my relatives who lived in Deland would likely have thought it a pretty ordinary day, at least until they heard news from my great-grandfather, the mayor of Daytona Beach. That city, along with others on the east coast, took some significant property damage, though no loss of life.

We are grateful.

Permalink | Read 861 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

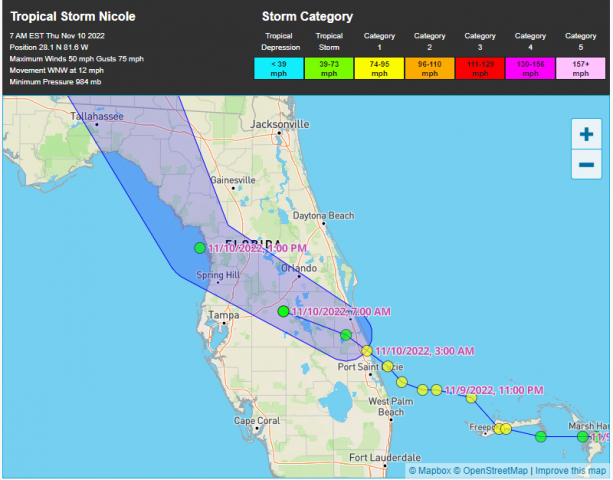

Nicole, having become a hurricane long enough to harrass the western Bahamas and southeast Florida, made landfall around 3 a.m. just south of Vero Beach, a little further north than we expected. I had been awakened a few times during the night by wind gusts and the steady sound of rain. When I got up for real around 4:30 (normal for me), it was clear that our decision to take in the wind chimes, orchid, and trash cans last night was the right thing to do, but everything else was fine.

Of course the day is not over yet; Nicole is currently around Davenport (where we ourselves were on Monday for a friend's birthday party), and heading our way at about 14 mph. But it's now a tropical storm again, and although we are still warned of gusts up to 70 mph, sustained winds where we are look to be less scary than predicted. (I'll take that!)

I greatly enjoyed a few early-morning hours on our back porch, watching what we've had so far from the storm. Because our porch faces west, and the winds were largely from the east, I enjoyed a safe haven with barely an occasional light breeze, while watching the trees whip around somewhat impressively.

Once again, the biggest damage to our neighborhood is likely to be flooding, but we haven't ventured out yet to investigate. Power outages usually come after the storm has passed, so we're not out of the clear there by any means.

Many thanks to those of you who have expressed your concerns, and offered their prayers. I expect to do at least one more update, more if anything untoward happens.

Permalink | Read 916 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

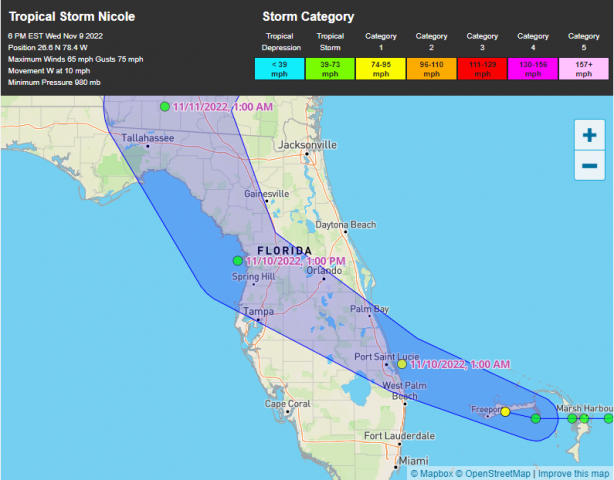

Nicole is not a hurricane yet, but looks to become one in the Bahamas, and come on shore around Ft. Pierce in the early hours of tomorrow morning, aka the middle of the night tonight. I fully expect to be awakened at least once by our ear-splitting weather radio, hopefully for nothing more serious than that for which it awakened us during Hurricane Ian, and again two days ago.

We were briefly out of "the cone" but are currently back in it, as the predicted path shifts. Of course, the area of strong winds is a lot broader than the cone, and we've been feeling its rain for days. They are still predicting peak sustained winds of 45-60 mph with gusts to 75 mph, which is a "strong tropical storm." Nicole should be off our west coast by 1 p.m. tomorrow, and I'll give an update when I can.

There's a reason we hadn't packed the generator up from the last storm. I hope we don't need it, but with the storm coming straight at us, the ground once again completely saturated, and rivers and lakes still at flood level or very close....

We're still pretty much prepared from last time, though we're waiting till tomorrow to bring things in from outside. My concern when I awoke this morning was for an appointment I had this afternoon at 3 o'clock. Based on today's weather, there was no reason I shouldn't have been able to take it: there's almost no wind yet, and the rain has been steady but not heavy. However, when it was clear that many businesses were deciding to close early, I chose to go in the morning as a "walk-in." I say I chose, but really, I didn't feel I had much choice. Call it a nudge from God, call it hyperactive anxiety—but I couldn't rest about it, and decided I might as well wait for hours there than be unproductive at home. As it turned out, they were able to fit me in quickly and I even made it to the library to pick up The Bellmaker, before it closed at noon. It was definitely the right decision.

Now we wait, hoping that our decision to wait till morning to batten the final hatches turns out to be a good one, too.

Permalink | Read 824 times | Comments (1)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

In George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, most people agree that the climax of the story is when Winston finally breaks under torture and betrays his lover, Julia.

Do it to Julia! Do it to Julia! Not me! Julia! I don’t care what you do to her. Tear her face off, strip her to the bones. Not me! Julia! Not me!

I've written before that I believe the climax to be elsewhere in the book, but Winston's failure here is also a powerful and decisive moment. We may hate Winston for his betrayal and despise him for his cowardice; perhaps instead we sympathise and just feel sad that he has been so completely broken. But how often do we ponder the truth that has been rammed home to me as we are once again directly in the sights of what threatens to become a hurricane.

We are all Winston.

I can keep my spoken and deliberate prayers under control for the most part. I can easily pray that God will diminish, disorganize, disperse, and divert the storm to wherever it will do the least harm. That's my standard hurricane prayer. But I can't deny that at another level, my heart is crying,

"Send it somewhere else! Not here!"

Permalink | Read 1031 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

It's time for more from my Favorite Left-Coast Liberals.

I don't like to post too much in one day, but with Election Day and an approaching hurricane fighting for my attention, sometimes it happens. I want to post this interesting DarkHorse analysis before the election results are known, because it's more fun that way.

The video is 23 minutes long. I particularly like that Heather agrees with me about the psycho-social probems of no longer voting together on a single Election Day. (Though I disagree with her comments about remote schooling.) And Bret's stories of his voting experiences are seriously funny, particularly the election integrity story at 14:57.

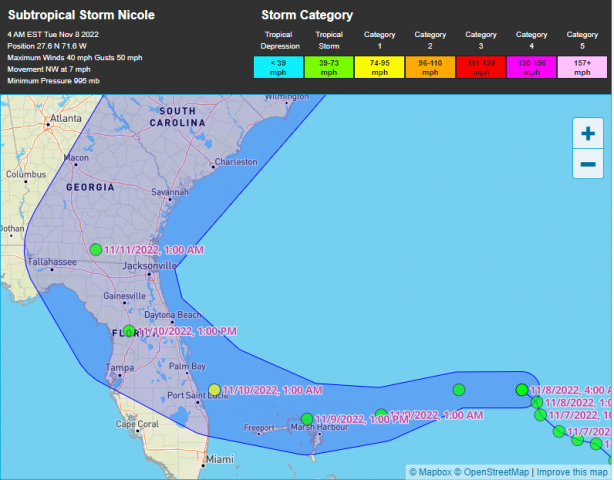

I think our weather warning system is broken. Or in a different time zone. There was absolutely no reason to awaken us with an ear-piercing blast from the weather radio, telling us that we are under a tropical storm warning. Yes, it's important for us to know that the prediction for what is currently Subtropical Storm Nicole looks to be worse for us than it was for Hurricane Ian. Many places around here are still flooded from the previous storm. And it's important for us to know that Nicole will probably reach hurricane strength before landing, and currently looks to pass straight over us as at least a tropical storm. I needed to know that, because I was not expecting anything more than a little wind and rain, which is not unusual for this time of year.

But there is absolutely nothing I needed to know about the storm that couldn't have waited a few more hours. My ears are still ringing and my head aching from standing with the radio in my hands, staring sleep-stupidly at the controls, trying to figure out how to shut it up. An event worthy of that kind of warning ought to be more immediately life-threatening, not about a storm that isn't expected to hit land for another two days.

Besides, I'm done with hurricanes for this year. It's mid-November! I know, that's technically still hurricane season, but quite unusual.

Permalink | Read 905 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Welcome back, Standard Time!

You hear a lot, from those in favor of year-'round Daylight Saving Time, about the many advantages of DST. Here's an article that claims better advantages for year-'round Standard Time. A few points:

More than 80 medical, education and religious organizations, including the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Society for Research in Biological Rhythms, would like to see the nation embrace standard time year-round.

Around the world, about 70 countries observe summertime daylight saving time, although changes are on the horizon. In October, a working group of European non-governmental organizations and researchers urged European Union member states to adopt permanent time zones as close as possible to their solar time. Also in October, Mexico’s Senate voted to abolish daylight saving time in favor of permanent standard time.

From the second Sunday in March until the first Sunday in November, we pretend the sun rises and sets an hour later than it does. Our minds may tolerate that, but our brains know better. They remain on sun time, which is aligned more closely with standard time. At noon on standard time in the middle of each time zone, the sun is directly overhead. Morning sunlight, the body’s most potent time-setting cue, tethers us to the Earth’s 24-hour day/night cycle. Exposure to sunlight soon after we awaken governs inner clocks that control sleep, alertness, mood, body temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, hunger, cell division and hundreds of other bodily functions. When we shift to daylight saving time, our morning light exposure drops. Our biological clocks fall out of sync. We pay a price: Daylight saving time’s lighter, longer evenings make it harder to fall asleep. We sleep less. Darker mornings make it harder to awaken, shrug off drowsiness and feel alert.

Having lived in several places in the Northeast as well as Florida, I understand why some people are attracted to DST. When we lived in Boston, it was disconcerting to see the sun so low in the sky in midafternoon! But why Florida's senators are leading the charge for permanent DST is beyond me.

I think Rick Scott has been a better senator than he was a governor, and I hope Marco Rubio is re-elected on Tuesday, but they're both idiots on this topic. In an e-mail I received today, Senator Scott said,

Changing the clock twice a year is outdated and unnecessary. We need to give families in Florida more sunshine, not less! I’m proud to be leading this bipartisan legislation with Senator Rubio that makes a much-needed change and benefits so many in Florida and across the nation.

They are clearly not representing Florida, as we elected them to do, because DST makes no sense here, closer to the equator. And it is embarrassingly obvious that you don't get a minute's worth more sunshine by changing the clocks.

Back to the article.

A person living in New York City who typically gets up at 7 a.m. will be forced to awaken before sunrise 164 days a year on permanent daylight saving time, according to an interactive chart on the website of the nonprofit Save Standard Time.... In Miami, on Florida’s southern tip, a person arising at 7 a.m. would awaken before sunrise a whopping 232 days a year on permanent daylight saving time. They’d miss exposure to the body clock-setting sunlight cue on awakening 7.6 months a year.

A friend who lives in Indiana, on the western edge of the eastern time zone, reports that under permanent DST the sun wouldn't rise until after 9 a.m. in the winter. At that point, I would already have been up and working for at least four hours! Even those who have more average schedules would be well into their work day while still in the dark.

Honestly, what do we gain by having light at night instead of in the morning? After a long, hard day of work or school, how many of our evening hours are actually productive? Or spent outside in the sun? Are they rather more often than not spent inside, watching flickering device-light rather than sunlight?

Back in March, our Senate voted in favor of permanent daylight saving time. The House, thus far, has shown more sense, and remains on board with Nature.

Year-'round DST would be unnatural and (dare I say it?) Eurocentric.

This is a general announcement to the Political World:

I have voted.

This means there is no point at all in calling me on the phone (mobile or home), texting me, sending me e-mails, waving signs in my face, or wasting our trees and your money, trying to influence my vote. It's done. It can't be changed.

The only thing I can do at this point is to continue to pray for the best outcome of the election.

So stop already.

When we visited the Netherlands with our overseas family, our trip to Madurodam was a hit with all of us. I can only imagine what a visit to Miniatur Wunderland in Hamburg, Germany would be like. A friend posted this on Facebook, and I knew the family members who are entranced by minatures needed to see it.

Unbelievably, the airport is just one "small" part of Miniatur Wonderland. Here's the official video (English version) that shows a lot more. In fact, it shows A LOT more, as in: this realistic, exquisitly-crafted, miniature world is decidedly Not-Safe-For-Grandchildren in places, as you can see.

If we ever get to Hamburg, I'm going to visit it anyway.

Permalink | Read 1017 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

There are a number of people—I certainly am one of them—who strenuously object to being unwilling medical guinea pigs in the matter of the COVID-19 vaccines.

I'm all for medical research, worked as part of a medical research team, and have been a willing human guinea pig in a few experiments myself. This work, when done carefully, knowledgeably, and ethically, is an essential part of scientific and medical advancement. But the ethically part is essential, and I don't think it's ethical to "enroll" masses of people in experiments for which there cannot possibly be adequate knowledge of the risks, and thus they cannot possibly give "informed consent." Plus, when there is no documented, adequate control group, not to mention that the experimenters have done their best to make sure there cannot be an adequate control group—well, then you've lost good science as well as ethics.

You're thinking I'm talking about the COVID-19 vaccines here, and I am—but that's not all. I don't know how many times we've been unknowingly subjected to these unethical experiments, but I do know that it has happened at least two other times in my lifetime.

Aspirin used to be the standard, go-to medication for children, even babies, with fevers or discomfort. I vividly remember the doctor recommending alternating doses of aspirin and acetaminophen when my infant daughter had a stubborn high fever. This was in the early 1980's, and for most people it worked just great. However, there appeared to be a possible correlation between aspirin use in children and young teens, in combination with a viral illness (often chicken pox), and a rare but sometimes fatal condition called Reye Syndrome. We had many doctors among our coworkers, and had no reason not to believe what they told us at the time: The decision to tell doctors and parents to avoid giving aspirin to children was a deliberate, national experiment: They thought aspirin caused Reye's Syndrome in children, but they couldn't prove it, so they hoped that if aspirin use went down dramatically, and so did the incidence of Reye, their point would be made. The disorder did, indeed, retreat significantly, whether through causation or merely correlation is still unknown. The cynic in me insists on pointing out that, whatever the stated reasons for this massive non-laboratory experiment, and whatever good might or might not come of it, one clear result was that a cheap, readily-available, and highly effective drug was massively replaced by one still under patent. The patent for acetaminophen (Tylenol) did not expire until 2007, and Tylenol was still reeling from the 1982 poisoned-Tylenol-capsules scare. Practically overnight, and with timing highly favorable to the pharmaceutical industry, Tylenol became the drug of choice for a large segment of the population.

The next example I remember of such a huge, non-controlled experiment happened in the early 1990's, and was not a drug but a parenting practice: the insistence by the medical profession that all babies never be allowed to sleep on their stomachs. Sleep position recommendations have flip-flopped several times over the years. The professionals never think it safe to leave that decision up to the babies and their parents, they just keep changing what it is that is "the only safe way for a baby to sleep." Personally, I think "whatever helps the baby sleep best" is almost always the right choice. (But I am not a doctor, nor any other medical professional, so make your own choices and don't sue me.)

Early in the 1990's the thought was that back-sleeping might reduce the incidence of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). Indeed, there was a decline after the "Back to Sleep" push went into effect, though once again the experiment was unscientific with no significant control group. Certainly there were still parents who put their babies to sleep on their stomachs, but if there was any widespread study of them I never heard of it, and indeed the data was necessarily corrupted because the pressure was so great not to do so that few parents talked openly about it. And doctors, even if they were well aware of the advantages of stomach-sleeping, could not risk mentioning them to their patients. I remember vividly the one young mother who, months later, confessed to the pediatrician that her son had always slept on his stomach. The doctor laughed, saying, "Of course I knew that! Look at how advanced he is, and look at the perfect shape of his head!" But stomach-sleeping is still very much a "don't ask, don't tell" situation.

These massive, uncontrolled, and to my mind unethical experiments on the human population are justified in the minds of many because, after all, they "did their job." Deaths from Reye Syndrome, SIDS, and COVID-19 have all fallen, so who cares how we got there?

Well, I care—and so should anyone who believes in the scientific method, the Hippocratic Oath, and open, honest, and ethical research.

Permalink | Read 1013 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

No, it's not St. Crispin's Day today. I'm a day behind. But I can't wait another year to post one of my favorite scenes from one of my favorite movies: The St. Crispin's Day speech from Kenneth Branagh's Henry V.

Permalink | Read 865 times | Comments (0)

Category Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]