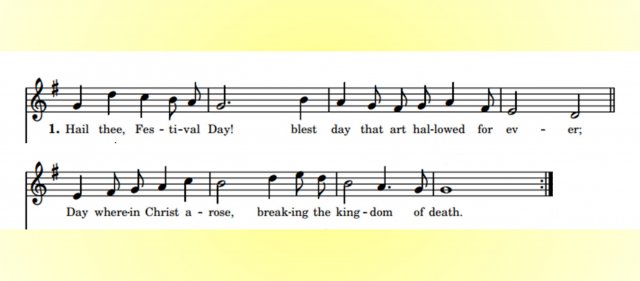

That will be our opening hymn this morning, and it's one of my favorites.

Happy Easter to all!

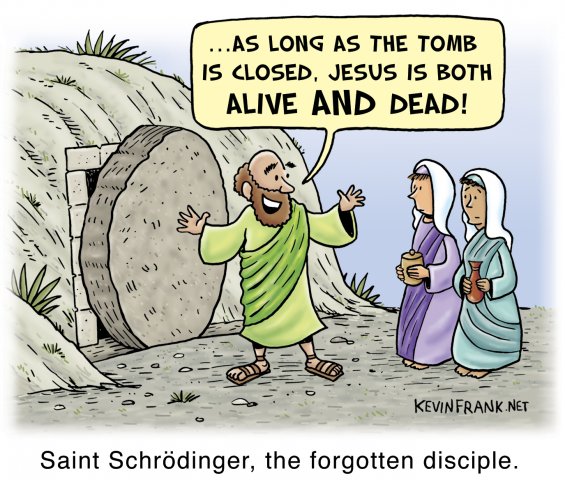

One of my favorite Easter cartoons, fitting for Holy Saturday, the day between Good Friday and Easter.

Permalink | Read 806 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

In honor of Holy Week and Easter, I present this 12-minute guide to the "What is it with all those different kinds of Christian churches?" question. You could be forgiven for suspecting this to be another offering from the Babylon Bee, but although it may be fun, it's serious, and surprisingly accurate. Being Anglican myself, I especially appreciate this line:

it's difficult to understand what Anglicanism really is, but don't worry, they don't understand it either.

Try not to get confused by the direction of the arrows from 10:20 to 10:34, which seem backwards to me. It must be one of those mysteries the Orthodox are always talking about.

Permalink | Read 804 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Our Palm Sunday service went well yesterday, and it was a joy to sing our anthem: Hosanna and Hallelujah (Ovokaitys/Thomson/Raney)—suitably modified because "Hallelujah" is verboten during Lent. But I'm fighting sadness because the "ordinariness" of the service, and the anticipated blandness of worship for Holy Week and Easter to come, is such a contrast to the gloriousness of worship services we have had in the past. The fact that our pared-down services are saving us a lot of work and stress, while appreciated, does not quite make up for the loss of joy.

It was good therapy to run into this photo from Palm Sunday, 2020, when affixing a palm to our front door was the best we could do, because our church had done the unheard of: The doors were closed—services shut down for the holiest and most joyful week of the Church Year.

It was but the beginning of sorrows. And this was not even the work of the state, which had exempted religious services from stay-at-home orders, but of our own Episcopal hierarchy. It was a sad and shameful time.

Our worship services may seem depressingly mundane to me these days, but they exist, and the choirs are singing, and we sit next to our neighbors once again—and even occasionally hug them. That's a lot to be thankful for: a loud hosanna!, and an even louder hallelujah! in six more days.

Permalink | Read 859 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I've admired Joel Salatin and his Polyface Farms for a long time, but many years have passed since I first read Everything I Want to Do Is Illegal. I'd lost track of him in the ensuing years, but he recently popped up after another YouTube video, in this Hillsdale College lecture. I hope you enjoy it; that man is right about many things. (15 minutes)

Permalink | Read 827 times | Comments (0)

Category Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Allow me to play devil's advocate here.

Tallahassee Classical School has made the news as far away as Australia because its principal was pressured to resign over (among other issues) an art lesson that included an image of Michelangelo's famous statue of David, which upset some children and parents. And once again, Florida, and those who objected to the photo, are being demonized because of it.

Don't get me wrong. We haven't made it to Florence yet, but you can bet David will be high on our list to see when we do. And if you're going to study classical art, you are going to run into a lot of images people could object to. Naked women, for example, are a whole lot more common than naked men. Rape, orgies, wars, graphic violence, eroticism, prejudice and "hate crimes"—it's all there, because great art reflects reality. Granted, it's far more tastefully done than what comes out of Hollywood, but still, it's there.

That said, there is SO much great classical art available, that were I teaching an art course to sixth graders, I'd probably leave that one out. Unfortunately, sixth graders are an age group that cannot be trusted to be mature about anything involving naked body parts or bodily functions. I remember how my own class of about that age reacted when a parent came into school and shared slides of his recent trip to Europe, including the famous Manneken Pis.

Unless you are choosing to be provocative, David is hardly necessary in a child's brief introduction to art.

If I had to choose one sculpture to represent Michelangelo, it would probably be his Pièta—but you can run into controversy there, too. Would people be so down on the parents if they had objected to the image for religious reasons, as some surely would have?

There's the point: different parents will find different things too objectionable to teach their young children. Which is why the school, very intelligently, had instituted the policy that parents are to be allowed to see the curriculum materials, and must be notified of anything that might be considered controversial. A blanket statement at the beginning of the course, something like the following, would have prevented a great deal of stress and misunderstanding:

This is a course in Renaissance Art, and as such will feature a great deal of Christian and Classical imagery, including religious themes, graphic violence, and unclothed people. We believe these works of art to be of sufficient importance to include them. Parents are welcome to view the materials and have their children excused from lessons they believe would be harmful.

I would hope for something similar with regard to music. You cannot study great Western music without including the music of the Christian Church; many schools no longer try, for fear of lawsuits, thus eviscerating their choral programs. Explain up front why you are including these great works, allow parents to excuse their children if they disagree—and get on with the job.

The school (on the advice of their lawyers, of course) is not giving any details about why the principal was pressured to leave. But I suspect it was less about the actual content of the class and more about violating the policy of not leaving parents in the dark.

One more point: most objections I hear against the parents who did not want their children to see the materials are mocking them for not being comfortable with pictures of naked bodies. That is, the parents are upset about something that their detractors have no problem with—which to my mind delegitimizes the objection. Everyone has something they consider out-of-bounds for being taught to their children; we should image that, instead of what we have no problem with, as the issue here.

I have no quarrel with parents who are up in arms at Sesame Street's decision to use cute little Elmo to push the COVID-19 vaccine on children. It's horrendous, despicable, a violation of the sacred trust between a show meant for children, and their parents.

But in a way I'm grateful that Sesame Street's writers, producers, and funders have finally come so far out of the closet. It's about time parents noticed.

There may have been a time when the show stuck with teaching basic reading and math skills, but once you decide that the purpose of your project is teaching children, it's only a small step to teaching them whatever you happen to think important—and before you know it, numbers and letters have taken a back seat to social and political activism. It reminds me of a young, idealistic teacher I heard interviewed the other day, who was in tears because she had become a teacher in order to "teach children social justice," and felt stifled under pressure to teach them academics.

Schools, and television shows aimed at children, have a widely-acknowledged—if mostly ignored—obligation to support the rights, values, and priorities of the children's families. Little by little both of these important institutions have blatantly and flagrantly violated that unwritten contract.

Maybe that's the best lesson Elmo can teach us.

Sometimes you have to post about all the terrible things happening in the world, and sometimes you just have to post about ... chocolate. Ann Reardon and How To Cook That present, "How big companies RUINED chocolate!" (17 minutes—have a taste!)

I don't remember where it was; Porter is sure it was somewhere in Switzerland, but neither of us can recall the city, let alone the store. What we do remember was that we bought several large bars of chocolate from specific countries, such as Venezuela, Panama, Ghana, and Cuba. If we'd known how great an experience that would be, we'd have bought a lot more, that's for sure. Porter's absolute favorite was the chocolate from Cuba; unfortunately, on our one adventure to that country, they were all trying to sell us alcohol and cigars, not the Good Stuff.

Here's another treat for you from Heather Heying's substack, Natural Selections: Stark and Exposed: It's the Modern Way. I'll include a small excerpt, but first, I'll quote a passage from Chapter 8 of C. S. Lewis's That Hideous Strength, the third book of his Space Trilogy, because that is what immediately came to mind when I was reading her essay.

The Italian was in good spirits and talkative. He had just given orders for the cutting down of some fine beech trees in the grounds.

“Why have you done that, Professor?” said a Mr. Winter who sat opposite. “I shouldn’t have thought they did much harm at that distance from the house. I’m rather fond of trees myself.”

“Oh, yes, yes,” replied Filostrato. “The pretty trees, the garden trees. But not the savages. I put the rose in my garden, but not the brier. The forest tree is a weed. But I tell you I have seen the civilized tree in Persia. It was a French attaché who had it because he was in a place where trees do not grow. It was made of metal. A poor, crude thing. But how if it were perfected? Light, made of aluminum. So natural, it would even deceive.”

“It would hardly be the same as a real tree,” said Winter.

“But consider the advantages! You get tired of him in one place: two workmen carry him somewhere else: wherever you please. It never dies. No leaves to fall, no twigs, no birds building nests, no muck and mess.”

“I suppose one or two, as curiosities, might be rather amusing.”

“Why one or two? At present, I allow, we must have forests, for the atmosphere. Presently we find a chemical substitute. And then, why any natural trees? I foresee nothing but the art tree all over the earth. In fact, we clean the planet.”

“Do you mean,” put in a man called Gould, “that we are to have no vegetation at all?”

“Exactly. You shave your face: even, in the English fashion, you shave him every day. One day we shave the planet.”

“I wonder what the birds will make of it?”

“I would not have any birds either. On the art tree I would have the art birds all singing when you press a switch inside the house. When you are tired of the singing you switch them off. Consider again the improvement. No feathers dropped about, no nests, no eggs, no dirt.”

“It sounds,” said Mark, “like abolishing pretty well all organic life.”

“And why not? It is simple hygiene. Listen, my friends. If you pick up some rotten thing and find this organic life crawling over it, do you not say, ‘Oh, the horrid thing. It is alive,’ and then drop it?”

“Go on,” said Winter.

“And you, especially you English, are you not hostile to any organic life except your own on your own body? Rather than permit it you have invented the daily bath.”

“That’s true.”

“And what do you call dirty dirt? Is it not precisely the organic? Minerals are clean dirt. But the real filth is what comes from organisms—sweat, spittles, excretions. Is not your whole idea of purity one huge example? The impure and the organic are interchangeable conceptions.”

“What are you driving at, Professor?” said Gould. “After all we are organisms ourselves.”

“I grant it. That is the point. In us organic life has produced Mind. It has done its work. After that we want no more of it. We do not want the world any longer furred over with organic life, like what you call the blue mold—all sprouting and budding and breeding and decaying. We must get rid of it. By little and little, of course. Slowly we learn how.

That Hideous Strength was written in 1945, but this doesn't sound nearly as ridiculous as it did when I first read it in college. "By little and little" we have come closer to this attitude than I could ever have believed.

From Dr. Heying's essay I will leave out the depressing part that brought Lewis's book to mind—but I urge you to read it for yourself. Instead, I'll quote the more uplifting end of the story.

Go outside barefoot. Stand there, toes moving in the bare earth, or grass, or moss, or sand. Touch the Earth with your bare skin. Stand on one foot for a while. Then the other. Jump. Stand with your arms wide and gaze upwards at the sun. Welcome it. Do not cover your skin and keep the sun’s rays at bay.

Learn to craft and to make and to grow and to build. Work in clay or wood or metal, in ink or wool or seeds. Build dry stacked stone walls. Mold forms with your hands and your tools. Add color to walls, to fabric, to food. Throw. Weave. Carve. Cure. Ferment. Fire. Braze. Weld. Create that which is both functional and beautiful.

Get cold every day. Go outside under-dressed or open your windows wide for a spell even sometimes in Winter or take a cold shower or immerse yourself in cold, cold water. You will be shocked. And you will be awake. And you will know that you are alive.

Also enjoy being warm. Be grateful for it. Come inside and find a cozy corner. Wrap yourself in a soft woolen blanket. Have a familiar by your side. Run your hands through his fur. Drink warm elixir from a handmade mug. Be present. Consider the past. Build the future.

Permalink | Read 1351 times | Comments (0)

Category Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Conservationist Living: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

As part of my recent long-term efforts to "get my affairs in order," I ran into this passage from one of my old journals.

Sunday, July 7, 1985

Today we went to the Episcopal church I'd wanted to try. I guess I'm just not an Episcopalian at heart. I love the way they do Communion (at the altar rail, common cup, with wine, and frequently). But otherwise it was too formal and "high church," yet without the splendor and dignity I remember from St. Paul's. Besides, the sermon was addressed to rich businessmen, which fit in with all the expensive cars in the parking lot.

Although I did not mention the name of the church, I'm certain it was the Episcopal Church of the Resurrection in Longwood, where, as it happens, we have been happily worshipping for the past 11 years.

The St. Paul's Church referred to is not the St. Paul's Presbyterian Church (PCA) in Winter Park, which we attended in the 1990's, nor the Episcopal church of the same name we so joyfully visited when we went to Chicago, but the St. Paul's Episcopal Church of Rochester, New York, where we fell in love with worship in the 1970's. St. Peter may be a very popular figure, but St. Paul certainly has his admirers as well.

Anyway, despite what I wrote in my journal, from the 90's onward I've come more and more to appreciate high-church services, with their emphasis on sacrament, worship, liturgy, Scripture, prayer, constancy, poetry, and beauty. The formality that used to make me uncomfortable I now recognize as the freedom of worship that comes from knowing the steps of a lovely dance, and I thrive in it. Not to mention that I can walk into a Catholic or Angican church in a foreign country and feel at home, because I know what's happening, even if I don't know the language.

My happiest worshipping years were at the St. Paul's in Rochester, where I first discovered liturgical worship (and my two favorite hymns, St. Patrick's Breastplate and Hail Thee, Festival Day!); the St. Paul's in Winter Park, when it was newly-formed and experimenting with liturgical worship (back in the days before the church, in my view, lost its way); and the all-too-few years when our present church enjoyed a more Anglo-Catholic approach to worship (read: more intricate and beautiful dance steps).

The individual steps toward change may be barely noticeable, but looking back 40 years can make you realize how far you've come.

It's no secret that I love hearing from Heather Heying and Bret Weinstein. I don't listen to half of what I want to of their videos, though I do try to keep sort of current with their DarkHorse podcasts. Theirs is a joyful, intelligent, informed, open-minded repartee that represents what I miss the most from the days when we lived in a university community. They would be such awesome people to have over for dinner! I couldn't keep up with them on the puns, but there are those in our family who could.

As much fun as they are to listen to, I still find the video format frustrating: slow, even at 1.5 speed, and without the convenient search and copy functions available in print. For that, I enjoy reading Heather's substack, Natural Selections. Here's one from December that I highly recommend: The New Newspeak. The primary topic is Stanford University's Elimination of Harmful Language Initiative. If you have the stomach for more than the examples Dr. Heying gives, you can find the source at that link.

As maddening what Stanford has done is, here is something else that caught my eye:

When I was a professor, creating and leading study abroad courses to remote places, I was told an amazing thing by a Title IX compliance officer. Thankfully, she did not work at my school, so I easily evaded her injunctions. She informed me that if, after I had spent years creating a program to go to the Amazon (as I had), someone in a wheelchair wanted to take my program, I would either need to figure out how to make that happen, or cancel the trip for everyone.

“The Amazon is not ADA compliant,” I told the confused young authoritarian. “If it were, it wouldn’t be the Amazon.”

“Then,” she announced with some relish, “you would have to cancel the class.”

That is the endpoint of this ideology. Life has to be made equally awful for everyone. Anything else would be unfair.

To which a commenter replied,

I can give a current example at a major West Coast medical school. We have an impressive series of locally created educational videos. Some are close captioned, and some cannot be for a variety of reasons. We now have a student (1 of 150) in the class that has trouble hearing. Because we cannot close caption it all, we have been instructed, in the name of "equity" to make sure that 149 students are deprived of seeing these videos and thus being forever less able to care for their patients so that this one person "does not feel bad". This is idiocy of the nth degree. And permutations of this happen continuously. The whole point is to make sure that graduating doctors know the minimum amount possible so that they are all equally stupid...I wish I were exaggerating.

If I were you, I would not see any doctor under 40. Heed my words.

Having two newly-minted doctors in the family, both well under 40, I can't quite agree with his conclusion. They are among the best and the brightest and most compassionate I know—I only hope their non-West Coast medical schools and residencies are not quite so far gone.

For much of my life, chocolate meant either Nestlé or Hershey. Nestlé tasted better, but Hershey gained points after I moved to Pennsylvania.

Eventually, Nestlé fell out of favor because of the way they push their infant formula, especially in third-world countries. Not to mention the fact that they suck massive amounts of water out of our Floridan Aquifer for their bottled water.

Hershey fell out of favor because, well, because Swiss chocolate is just better, period. And my chocolate budget grew bigger.

Now Hershey has given me more reasons to stick with my Toblerone, Ovomaltine (NOT the Americanized junk of similar name), and other amazing Swiss brands. I've also grown fond of Ghirardelli, though it doesn't pay to look too closely at their corporate values, either. I try to judge products by their quality rather than their politics, as long as the company's political views aren't shoved in my face.

Annoyed as I am with Hershey, which is doing just that, they've also, albeit indirectly, given me this comedy sketch, so I thank them. (And it's not even the Babylon Bee this time.)

However, I'm not going to be shopping at ihatehersheys.com. My chocolate budget isn't that big.

If you're not a Babylon Bee fan, feel free to skip. If you are, enjoy! The clip will look as if it's ending before the punch line, so watch till they start the ads.

I think the Bee produces the best comedic commentary on current events since That Was the Week that Was from the old Smothers Brothers show (for which, sadly, I did not find a representative clip).

(There are times when I could think the situation is the other way around: the earth has been taken over by space aliens, and we didn't even notice.)