A liberal Democrat Constitutional lawyer speaks on why everyone should be concerned about illegal behavior on the part of the FBI, and why he's involved in a lawsuit against "his own" party's actions. The video is long (26 minutes), and more relevant at the beginning than the end. You can get a good summary at about minutes 13-17. Or just this:

The Constitution is not only for people you agree with; it's primarily designed to protect people you disagree with, people whose views are out of fashion, people who everybody wants to see prosecuted.... I'm going to especially, especially, focus on people who are having their Constitutional rights violated by my political party, by my people who I voted for ... that's the special obligation that every citizen has to hold to account those who are on your side.

Also, look at about minutes 5-10, covering search warrants, and the dangers of having our whole lives on our cell phones. One day, out of the blue, we may find government officials seizing our phones, and our computers, and our external drives, ruining our businesses and even our lives in ways that cannot be redressed, even if we are eventually vindicated in court. So it behooves us to be grateful for those lawyers and politicians who seek to enforce strict Constitutional limits on when and how that is allowed—even against the most heinous people. (Cue the A Man for All Seasons devil and the law speech.)

Also, who knew (about 8:30-9:15) that it's safer—from the point of view of privacy—to store medications in a medicine cabinet rather than in a drawer?

Hubris: Exaggerated pride or self-confidence

The original of this article by George Friedman, entitled "John F. Kennedy and the Origin of Wars Without End," is at Geopolitical Futures and is currently behind a pay wall. I was able to read it because Porter is a subscriber. A few quotes won't do it justice (though you'll get them anyway), but I was able to find the same article here at PressReader.com, so you can check it out for yourself, at least for now.

Friedman's basic idea is that John F. Kennedy sealed the fate of future American military action in his inaugural address:

“Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and the success of liberty.”

This view of America as the the world's police force, making the world safe for democracy, was not new, of course. It was President Woodrow Wilson who led us into World War I with that phrase about democracy. In World War II, President Roosevelt considered the United States as the world's savior, but "carefully calculated the cost." Eisenhower calculated the risks and benefits and wisely refused to send American troops to Indochina.

Kennedy wrote a blank check from his country. ... In assuming the burden, he assumed the cost of war if needed, and he did not ask the question of whether our hardships would bring success or failure, and at such a price that the nation might not be able to bear it militarily, financially or morally.

There were three wars following Kennedy’s stated principles that lasted for many years and were unsuccessful: Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq. But they were only the long and agonizing cases. The United States used military force in Iran during the hostage crisis but failed to achieve its desired outcome. The United States invaded Grenada. It succeeded, I suppose. The United States sent troops to Beirut and withdrew when hundreds of Marines were killed by explosives. The United States succeeded in Desert Storm. It conducted an extended bombing campaign in defense of Kosovo. And it has sent troops into Libya, Syria, Chad and northern Africa.

I am no pacifist, but the tempo of operations imposed on the U.S. military and the widely varying environments it went into, frequently with a mission that was opaque, made little sense. In World War II, there was a clear moral and geopolitical reason for combat, a clear if flexible strategy that would withstand reversals. Most important, the military was configured for this war. Training a force takes time, and a force cannot be trained for “whatever comes up.” Having been trained to face the Soviets in Germany, the U.S. military was then unreasonably asked to fight limited wars in the jungle, the desert and so forth. In other words, it was asked to go anywhere to fight any foe and protect any friend. So that’s what it did.

If you go into combat without an appropriate force, and with a sense of invincibility, you may not lose, but you won’t win. And if you go in unprepared for the terrain, weather and horrors of the battlefield, the failures will mount, the politicians will deny any failures, the machine will pump more soldiers into the war, and the public will rightly determine that the war was a horrible failure. And then the soldiers who broke their hearts trying to win will feel betrayed by their nation.

Kennedy’s doctrine, then, should be expunged from our minds. That doctrine leads to endless war and continual defeat. War is not an action designed to do good. It is the use of overwhelming force against an opponent that threatens your nation’s fundamental interest. War is not an act of charity for deserving friends, not even an act of vengeance for a vicious enemy.

A fundamental foundation for peace is an unsentimental understanding of geopolitics, the discipline that distinguishes sentiment from necessity, capability from boast, and the enemy who matters from the one who doesn’t. ... Kennedy assumed that the U.S. could afford to fight any enemy anywhere. It can’t. And Washington better be certain that the next war it fights can be won, and that the next enemy is actually an enemy.

Note that this article was written in September 2021, almost six months before the United States became involved in yet another, very costly, war to make the world safe for democracy.

It's time for another in my series of YouTube channel discoveries. I resent the amount of time it takes to get information out of the video/podcast format, but it's so popular these days that it has become a major source for interesting and helpful information. So I'm unapologetically recommending another video channel: Bret Weinstein and Heather Heying's DarkHorse Podcast. That link is to their podcast website, but I usually watch it via their two YouTube channels: Full Podcasts, and Clips. Full podcasts are long. Very long. They would be great on a car journey, not so much in everyday life, unless you have a lot of work to do that doesn't require much thinking. I can fix dinner while listening to a podcast, but I sure can't write a blog post. Clips, on the other hand, are much shorter (maybe five to twenty minutes). Focussing on clips means I miss good insights, but giving in to Fear of Missing Out is a pathway to madness.

I've mentioned Bret and Heather before, in my Independence Hall Speech post, so it's about time I gave them their due. I must also give due credit to the good friend who introduced me to DarkHorse, as well as to Viva Frei, and remained patient with me even though it was at least a year later before I finally got around to checking them out. Thank you, wise friend. (There's but an infinitesimal chance he'll actually see that, but still, credit where credit is due.)

By way of introduction, the following quotes are from their DarkHorse Podcast website:

In weekly livestreams of the DarkHorse podcast, Bret Weinstein and Heather Heying explore a wide range of topics, all investigated with an evolutionary lens. From the evolution of consciousness to the evolution of disease, from cultural critique to the virtues of spending time outside, we have open-ended conversations that reveal not just how to think scientifically, but how to disagree with respect and love.

We are scientists who hope to bring scientific thinking, and its insights, to everyone. Too often, the trappings of science are used to exclude those without credentials, degrees, or authority. But science belongs to us all, and its tools should be shared as widely as possible. DarkHorse is a place where scientific concepts, and a scientific way of thinking, are made accessible, without diminishing their power.

We are politically liberal, former college professors, and evolutionary biologists. Among our audience are conservatives, people without college educations, and religious folk. We treat everyone with respect, and do not look down on those with whom we disagree.

Needless to say, I often disagree with them—sometimes strongly—but more often I find their insights at least reasonable. And it is always interesting to listen in on their conversations. I take great pleasure in hearing smart people interact with each other—assuming they're polite, which Bret and Heather always are. It's also particularly satisfying in the rare circumstances when I find I know something that these highly intelligent people, with much greater knowledge than I, don't. I love living in Florida, at least in its current free-state situation, but I've never gotten over the loss of the intellectual stimulation that came with having the University of Rochester within walking distance.

I find DarkHorse so diverse and absorbing that it's really hard to limit myself to three examples here. But you can always check it out for yourself. Here are a couple of hints: Bret and Heather's speech is measured enough that I can hear it at 1.5x speed, and Porter can manage 2x. I prefer not to speed it up, but it is a time saver. An ever greater help with the full podcasts is that, once the livestream is over and the video is set on YouTube, you can hover your mouse over places along the progress bar and see where a particular subject begins and ends. I sure wish more long videos would provide that information.

Warning: Objectionable language occurs, though rarely, in the DarkHorse Podcasts.

Multi-age education (11 minutes)

When science is not science (9 minutes)

Wikipedia redefines recession (19 minutes)

I'll close with some advice from their website, which makes me smile every time I read it.

Be good to the ones you love,

Eat good food, and

Get outside.

Permalink | Read 1413 times | Comments (0)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] YouTube Channel Discoveries: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Some people are fascinated by large numbers; others just tune out when they see them.

Many people don't trust the statistics from the Centers for Disease Control. Me? I don't trust their proofreaders. How else to explain this, from one of their vaccine safety updates:

CDC has verified 131 myocarditis case reports to VAERS in people ages ≥5 years after 123,362,627 million mRNA COVID-19 booster vaccinations

In case you are one of those whose minds go on strike in the presence of large numbers, that's over 123 trillion vaccine boosters. More than 15,000 boosters for every person on the planet. Put another way, if, instead of getting a shot, each person boosted "according to the CDC" contributed twenty-five cents, a mere quarter, the entire national debt of the United States would be paid off.

Foolish speculations over an "obvious" error? I don't think so. If we don't pay attention to numbers, we will make mistakes, some of them fatal. Bridges will collapse. People will be killed by medications that should be life-saving. Bombs will land in the wrong places. Citizens will be misled. Disastrous policy decisions will be made.

If I can't trust the "123,362,627 million" part of the sentence, what makes me think I can trust the "131" part?

Numbers matter. Accuracy matters.

It takes a lot to get me to watch a 2+ hour movie I'm pretty sure I will not like. One thing I can say about watching V for Vendetta—it was almost as negative an experience as I expected it to be. I put myself through the agony because Brett and Heather, among others, have made the connection between the movie and President Biden's recent Independence Hall speech.

I think we need to take very seriously the fact that not only is there the evidence that these people have fascist inclinations ... but they are now actively playing with the symbolism ... that blood-red background ... the ranting demagogue. What does it allude to? It alludes to V for Vendetta, which is a movie adored by the Left.

I thought it might be worth checking out.

Was it worth two hours of my time? I'm not sure. I'll say flatly: It was an awful movie. As a film, I see nothing to commend it. On the other hand, to know that it was made in 2005 and see the parallels to recent years (including the deadly virus and government—pharmaceutical business—media collusion) does make it somewhat interesting. As dystopias go, however, I think Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, which was also an unpleasant experience, is more important.

What I find most confusing, however, is why the president's speech writers and stage designers would want his audience to make a connection between the speech and the movie. V for Vendetta can only be "adored by the Left" if you see the demagoge and the tyrannical government as being of the Right—those President Biden insists on calling "MAGA Republicans." Coming to the movie only after having seen the speech, however, I had an entirely different view.

The invocation of V for Vendetta is not accidental, of that I am sure. It's manipulative, certainly. It may also be brilliant. Whether one sees the speech as hateful or hopeful, diabolical or innocent, President Biden's supporters, reminded of the movie, will of course see themselves in the heroic role, and—this is the brilliant part—so will his stated enemies. This is a movie that might have been designed to foment anger, hatred, insurrection, chaos, and above all self-righteousness.

Qui bono? Who profits from anger and fear? Who benefits from chaos and division irrespective of party, partisanship, values, and goals? Do you ever feel that someone is pulling our strings and doesn't care a bit whether it's Black Lives Matter or the Ku Klux Klan, as long as hatred and violence reign? What are the odds that this is unrelated to the design of the setting and text of Biden's speech?

Qui bono?

I couldn't bring myself to watch the speech that President Biden recently gave at my home-town Philadelphia's Independence Hall. That's not a partisan reaction; I generally try to avoid such events, and treated President Trump the same way. I prefer to judge presidents by their actions; their talk always makes me queasy.

But I heard so much about this one that I had to check it out for myself. Instead of watching, I read a transcript, which allowed me to leave behind the freaky red lights and odd Marine guard, leaving only the content to interfere with my blood pressure. Since many of my readers will not have seen the speech, and I don't want to have to deal with copyrighted photos, I'll attempt a brief description of the backdrop that sent me flying to the transcript.

The Independence Hall building was decorated in an ostensibly patriotic scheme: the middle red, the top white, and the sides blue. Unfortunately, the word that came to my mind was not patriotic, but garish. Angry, even. This was the long-distance view, which some have called more benign; the close-up shot, when President Biden was speaking, with his two Marine guards behind and to the sides, was a wrathful and intimidating red. If you question how a lighting scheme can look angry, you can find plenty of images online and judge for yourself.

I thought I'd walked into a dystopian movie scene. All I could think of was, "What are they trying to convey to the audience?" Every public encounter these days is theater, and I don't believe it was accidental. But I certainly don't understand it, especially for a speech that tried to invoke light and angels and the "willingness to see each other not as enemies but as fellow Americans." The only angel brought to my mind by the lighting was a fallen one. As one of my friends commented, "To what constituency was the eerie, hellish setting supposed to appeal?"

The speech, even extracted from the setting, left me with the same question.

As I said, there seemed to be an attempt to invoke something positive, with phrases like these: sacred ground; our better angels; all created equal; a beacon to the world; prosperous, free, and just; a nation of hope and unity and optimism; courage; free and fair elections; come together; unite behind the single purpose of defending our democracy; unlimited future; we can see the light; America’s economy is faster, stronger than any other advanced nation in the world; there is not a single thing America cannot do; I’ve never been more optimistic about America’s future.

Despite the attempt at portraying goodness and light, however, the impression left in my mind by the speech was very, very dark. The angry red color perfectly presaged the color of the speech, which even when the president was speaking of positive things used images of fire and burning.

"I’m an American President," Mr. Biden said, "not the President of red America or blue America, but of all America." That sounded hopeful. So did "The soul of America is defined by the sacred proposition that all are created equal in the image of God. That all are entitled to be treated with decency, dignity, and respect."

Unless you happen to be a "MAGA Republican."

Who are the MAGA Republicans the president referred to so often in his speech? Despite his efforts to fit his opponents into some dark, backwoods corner of "extremism," the president has flung the tent of disfavor so wide as to cover half the country, including not a few Democrats like myself. I have never been a fan of former President Trump, but the further I went into this speech, the more I knew that neither he nor his supporters deserved the words President Biden tarred them with: equality and democracy are under assault; threatens the very foundations of our republic; extreme ideology; dominated, driven, and intimidated by Donald Trump and the MAGA Republicans; a threat to this country; do not respect the Constitution; do not believe in the rule of law; working ... to give power to decide elections in America to partisans and cronies; promote authoritarian leaders; fan the flames of political violence; a threat to our personal rights; a “clear and present danger”; embrace anger; thrive on chaos; live not in the light of truth but in the shadow of lies; will put their own pursuit of power above all else; inflammatory; dangerous; look at America and see carnage and darkness and despair; spread fear and lies; white supremacists; calling for mass violence and rioting in the streets; believe that for them to succeed, everyone else has to fail.

Having found the scapegoats, he urges the faithful to join him in stopping the evildoers: it is within our power, it’s in our hands—yours and mine—to stop the assault on American democracy; we have to defend it, protect it, stand up for it—each and every one of us; there are dangers around us we cannot allow to prevail; I will not stand by and watch—I will not—the will of the American people be overturned; I will defend our democracy with every fiber of my being, and I’m asking every American to join me.

A call to arms? An incitement to violence? Despite words against violence (we do not encourage violence; we each have to reject political violence), it's hard to see the speech as benign. From the inflammatory lighting to the verbiage, the speech felt to me like an intentional threat. The president used the word "violence" ten times, "threat" nine times, and "MAGA" thirteen. In the midst of all this, his attempts at evoking light were, like the lighting behind him, garish rather than illuminating.

Whatever the intent was, whoever the constituency it was expected to appeal to, my own reaction was disgust at the hateful and harmful lies my president was willing to tell about his political opponents. And so of course I had to take action, to do something socially and politically significant.

I designed a t-shirt.

It was inspired by a comment of Porter's, and by stories of non-Jews who chose to don their own yellow stars when the Nazis began separating and demonizing their Jewish neighbors. I can't call myself a MAGA Republican, so....

The best commentary I've heard about the speech is by Bret Weinstein and Heather Heying, about whom I'll have more to say in a subsequent post. Suffice it to say now merely that they are evolutionary biologists who tend to relate everything in life to their field, classical liberal academics whose observations often run afoul of modern academic dogma. Sometimes I agree with them, sometimes I disagree—but I always enjoy listening in on their discussions. Perhaps I like what they say here because they agree with me on some key points. :) I discovered their commentary only after I'd drawn my own conclusions.

The clip below is the one relevant here, from 1:06:41 to 1:24:05. If I've done it right, that's the part you'll see if you click on the embedded video.

I'll leave you with my favorite part of President Biden's speech, which may stand out as the single most truthful statement any president ever made:

Too much of what’s happening in our country today is not normal.

How do we return to normal—or to something better? My own suggestion—possibly more helpful than donning a t-shirt—is that we need to get to know each other better on the ground level. It's easy to hate groups of strangers, not so easy to hate the person of polar-opposite political views who sings next to you in choir. There's also little as eye-opening as travel—what a tragedy it is that pandemic and inflation have crushed that impulse for so many. I can think of no better antidote to this speech than the experience of a good friend of ours, as liberal a Democrat as President Biden could wish for, who was in need of major assistance far from home, and was aided by the kindest and most helpful people—in a hotbed of "MAGA Republicans." I wouldn't wish her troubles on anyone, but if we all had more boots-on-the-ground experiences with our diverse fellow Americans, we'd find ourselves much less willing to demonize them.

Sometimes, you just have to make a meme. It's so much more fun than getting angry about the relentless and ubiquitous anti-meat propaganda these days.

I'm told that someone found this ad for Governor Ron DeSantis objectionable, and that it has disappeared from television. I wouldn't know; I saw it because it still shows up as an ad on some of the YouTube channels we follow. (I haven't figured out how to block ads on either my phone or our Roku—any ideas?)

I love it; it is so DeSantis, and so Florida. I had to go to Australia to find a good copy to post, but here it is, one minute of fun:

It started innocently enough, with an e-mail from AncestryDNA informing me of an additional trait revealed by my genetic makeup: my inclination to seek out or to avoid risky behavior. I could have predicted the result: I definitely prefer to avoid risk. Except, of course, that if I were as risk-averse as they say I am, I wouldn't be about to write something that could get me cancelled by Facebook.

The trigger was in one of Ancestry's explanatory paragraphs:

The world around you also affects your appetite for risk. Younger people and folks who were assigned male at birth report taking the most risks, which may be influenced by environmental factors like social rewards. Some influences are closer to home, like whether your parents encouraged risk taking. Also, our popular understandings of risk may skew more toward physical and financial risks than emotional ones. It's not only risky to do things like step onto a tightrope blindfolded. It's also risky to be honest about your feelings, admit ignorance, and express disagreement. In other words, it's risky to be yourself.

Really, Ancestry? Folks who were assigned male at birth? You mean men? If there's one place I'd expect to be free from this massacre of language, not to mention of reality, it would be a company that makes its money telling people about their chromosomes. When the attendants at my birth announced, "It's a girl!" they were not assigning my sex, they were revealing it, and AncestryDNA should know that better than anybody. Is there any point in trusting the other things they say about my genetics if they think that whether I was born with XX or XY chromosomes is something that was chosen by the birth attendants? Maybe the doctor determined my skin color, too? And the nurse decided I would be right-handed? Humbug.

When American women began coloring their hair, the object was to appear natural (no purple!). Clairol's popular commercial advertising their product contained the catchphrase, "Only her hairdresser knows for sure." My ophthalmologist amended that to, "... and her eye doctor."

While examining my eyes, he had casually announced, "You're actually a blonde." My hair, at that time, was brown, with a smattering of grey. All natural, I might add. A towhead as a child, I had gradually morphed into a brunette. Or so I thought.

"How do you know that?" I questioned.

"You have a blonde fundus. You can dye your hair and fool most people, but your eyes know the truth."

A brand-new story is on its way from S. D. Smith, creator of the Green Ember series. There's a trailer at JackZulu.com, and I'm sure more information will follow.

In the meantime, two of the Green Ember books are currently free for Kindle, with more to come next week. But really, the regular Kindle prices are so low, it's not worth stressing of you miss the sales.

In my review of Michael Pollan's book, Cooked, I noted what a professional chef told him about using salt.

"Use at least three times as much salt as you think you should," she advised. (A second authority I consulted employed the same formulation, but upped the factor to five.) Like many chefs, Samin believes that knowing how to salt food properly is the very essence of cooking, and that amateurs like me approach the saltbox far too timorously. ...

Samin prefaced her defense of the practice by pointing out that the salt we add to our food represents a tiny fraction of the salt people get from their diet. Most of the salt we eat comes from processed foods, which account for 80 percent of the typical American's daily intake of sodium. "So, if you don't eat a lot of processed foods, you don't need to worry about it. Which means: Don't ever be afraid of salt!"

Clearly, chef Gordon Ramsay agrees. Spend three minutes watching this video of him demonstrating how to make the "perfect burger" at home, and you'll see him seasoning the creation—adding salt and pepper in generous quantities—seven separate times:

- burger side 1

- onions

- burger side 2

- burger again

- cheese 1

- cheese 2

- lettuce

After assembling the burger he finishes it with one more healthy dose of pepper.

If you're wondering why it is that hamburgers from your favorite restaurant taste so good, take note, and see if using a freer hand with seasoning makes a difference to your home cooking.

What I still don't understand, however, is how one eats such a creation. It looks fantastic, but who has a mouth that can get around such a thing? We're not snakes! That's my problem with restaurant burgers, which taste so good but which I can't manage to eat without requiring a fork to clean up everything that oozes out the sides, followed by a large stack of paper napkins and/or a trip to the restroom to wash my hands. Any suggestions?

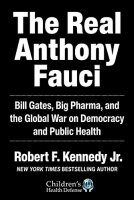

The Real Anthony Fauci: Bill Gates, Big Pharma, and the Global War on Democracy and Public Health by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. (Skyhorse Publishing, 2021)

The Real Anthony Fauci: Bill Gates, Big Pharma, and the Global War on Democracy and Public Health by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. (Skyhorse Publishing, 2021)

As a teenager, I flirted with the Kennedy adulation so common among my peers. I was too young to know much about John F. Kennedy, though I vivdly remember proudly carrying a note from my mother explaining that I was late coming back to school from lunch because I had been watching Kennedy's inauguration on television. (We walked home from school for lunch every day; to some people, that probably makes me seem old enough for it to have been George Washington's inauguration—were it not for the television reference.) I barely even remember JFK's assassination, since I was at the eye doctor's at the time and thus missed the reactions of my classmates. However, I spent hours glued to the television during Robert F. Kennedy's funeral in 1968, and genuinely grieved. But that was then; the subsequent years gradually took the shine off both the Democratic Party and the Kennedy family for me. Our two years of living in the Boston area and hearing from the common people their stories of oppression at the hands of Kennedys sealed the deal.

So why would I choose to read a book by Robert F. Kennedy's own son and namesake? Why would I wade through a book that castigates Republicans and has nothing but admiration for his famous family? Why would I spend my two weeks at the beach reading a book of nearly 1000 pages without even the excuse of it being a Brandon Sanderson novel? (There's a confusing difference in number of pages between the Kindle version and the hardcover, with the former being nearly twice the latter. Whatever—it's long.)

Two reasons, maybe. It was recommended by someone whose opinions I respect, and although the book costs $20 in hardcover, it is only $2.99 in Kindle form.

I'll state upfront that the book is controversial. My first reaction was, "If this is true, why is Dr. Fauci not in jail? If it's not true, why isn't he suing Kennedy for libel?" Speaking of libel, feel free to read Kennedy's Wikipedia entry, which is a pretty good example of the way controversial topics are handled these days. You don't like what someone says? Why bother to refute his arguments when you can brand him a conspiracy theorist, a purveyor of false information, and shut him down? But go ahead, read the accusations. Then read the book.

Despite the seriousness of the subject, it is somewhat amusing and even encouraging to find a die-hard Democrat who is willing to skewer not just Republicans but much of his own party as well (though not the Kennedys themselves), while admitting that the hated Republicans have sometimes been closer to the truth, and revealing that presidents of both parties have been helpless in the hands of the bureaucrats whom they have been forced to trust.

Don't let the number of pages in this book dissuade you. Reading it went surprisingly quickly, not only because it is interesting, but because so much of it is pages and pages and pages of footnotes. If it's misinformation, it's certainly well-documented misinformation.

It did take me a while to get into the book. The first section, which is about COVID-19, is over-long and harder to read than the rest of the book. Perhaps because this problem is new and ongoing, Kennedy is not at his best, sometimes overly polemic. He's still angry in the rest of the book, but handles it better. Maybe I just got used to it. Or maybe I got angry, myself.

This is not a book to take my word for. Much of its value comes in its extensive documentation, its references and endnotes—not that you need to read them all, even if you could, but that you need to know the documentation is there. Kennedy is not just some politician spouting off his baseless opinions. In addition, he makes an effort to update both information and references online.

I will not provide here my usual selection of quotations. (That's not to say I won't produce a few in subsequent posts.) Instead you get my own very brief and inadequate summary, the table of contents, and a subset of the questions swirling in my mind—some I have been asking for decades, others generated through reading The Real Anthony Fauci.

The Précis

The health and safety of America's people, along with that of much of the rest of the world, has for decades been held hostage by the iron grip of an unholy alliance among the federal agencies charged with that responsibility, the pharmaceutical industry, our research universities, a few quasi-charitable organizations (such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation), and—come late to the table but enormously powerful—the gate-keepers of information (from CNN to Google). There's no reason to call it a conspiracy; "cartel" and "oligarchy" are the words that spring more readily to mind. The combination of good intentions (to put the best face on it), a great deal of hubris, and the power to acquire and control unimaginably vast sums of money qualifies as a man-made disaster of the highest magnitude. During my five-year tenure as a researcher at a major university medical center, I saw only the tiniest slice of the world of government grants and the network that controls academic publishing, but it was quite enough to make Kennedy's revelations believable.

The Contents

- Mismanaging a Pandemic

- Arbitrary Decrees: Science-Free Medicine

- Killing Hydroxychloroquine

- Ivermectin

- Remdesivir

- Final Solution: Vaccines or Bust

- Pharma Profits over Public Health

- The HIV Pandemic Template for Pharma Profiteering

- The Pandemic Template: AIDS and AZT

- The HIV Heresies

- Burning the HIV Heretics

- Dr. Fauci, Mr. Hyde: NIAID's Barbaric and Illegal Experiments on Children

- White Mischief: Dr. Fauci's African Atrocities

- The White Man's Burden

- More Harm Than Good

- Hyping Phony Epidemics: "Crying Wolf"

- Germ Games

The Questions

- Why has there been so little attention given to discerning why disorders such as autism, ADHD, asthma and other autoimmune diseases, allergies, and a variety of mental health issues have become so rampant?

- Why are we more concerned with selling highly profitable drug treatments and permanent surgical alterations instead of asking ourselves what might be in our water, our air, our food, our medical treatments, or our society that has caused so many boys to decide they need to be girls, and vice versa?

- Why do we quietly accept the marked deterioration in the health of our people after over a century of astonishing improvement?

- Why are those in our federal government who hold the solemn duty of safeguarding the nation's health allowed to reap huge personal profits (or any profit at all, for that matter) from vaccines and other products of the pharmaceutical industry? How is it not an infernal conflict of interest that the authorities responsible for declaring a new drug "safe and effective" stand to make a great deal of money if they give it their stamp of approval?

- Why was so much effort—and an unimaginable amount of money and other resources—put into developing and distributing COVID-19 vaccines, while the most obvious and most important question was ignored: How do we treat this disease?

- In the early months of the pandemic, boots-on-the-ground physicians successfully treated COVID-19 patients by repurposing inexpensive, already-approved drugs. Why were these doctors first ignored, then demonized, and their remedies (legal, with a long record of safety) pulled off the market by underhanded means?

- Why did we repeat with COVID-19 so many of the mistakes we made when struggling with AIDS in the 1980's?

- Why was the AIDS picture so different between America and Africa?

- Why are pharmaceutical companies, and charities such as the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation, allowed to dump on Africa, at significant profit, drugs and vaccines that have been deemed too dangerous for Americans?

- Why does much of our drug and vaccine testing take place in Africa, where the rules of proper research, record keeping, and informed consent can be ignored, and adverse events conveniently buried?

- Malaria used to be prevalent in the United States. Why has so much effort been spent on developing a still-mostly-ineffective malaria vaccine and so little on simple public health measures that might help eradicate it in Africa?

- Why has the United States government been sponsoring the development of biological warfare agents, through a loophole in international treaties?

- Why is our government outsourcing this biological warfare work to China, where regulations are lax and procedures known to be sloppy? Not to mention that China is known for industrial espionage and theft of intellectual property. Whoever imagined that it might be a good thing to avoid America's rules of legitimate research procedures while in all likelihood handing deadly technology over to a powerful country with whom our relations are uncertain at best?

- Why have we allowed our medical institutions and research universities to become so completely dependent on federal and industrial funding that their work is controlled and compromised?

- Why and when did we give up on the practice of scientific inquiry that has served so well in the past, and enshrine Science as a religion, wherein disagreement and debate, once necessary to the process, have become unspeakable heresy?

- Why did our COVID response appear to be so experimental and bumbling at the start—I remember saying, "Give them a break; they are doing the best they can with too little data"—when the strategies the government employed had actually been designed, simulated, planned for, and practiced for years, through multiple presidencies?

- And perhaps the most important question of all: Qui bono? How did the COVID-19 pandemic become the vehicle for a record transfer of wealth to the super-rich? Follow the money. Power corrupts; power over money corrupts exponentially.

There's more. Much more. Considering what Kennedy has discovered, the book turns out to be far more logical, documented, and measured than one has a right to expect. It's not everyone who can report rationally on something so shocking. This would be me:

Whatever your party affiliation or lack thereof, you owe it to yourself (and if you have children, especially to them) to invest $2.99 and a few hours in The Real Anthony Fauci. I'm at a loss as to how to confront the problems it reveals, but shedding some ignorance and blind trust is a start.

Turns out I'm admiring a Kennedy again. It only took me half a century.

Permalink | Read 1813 times | Comments (2)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Shame on us, Florida!

A 25% voter turn-out? Are you kidding me?

I'll admit that I wasn't thrilled by yesterday's primary election. The Democratic canditates were for the most part so disappointing I often found it hard to figure out the "least worst." This life-long Democrat has begun contemplating more seriously the idea of switching parties, just to be able to vote in the more interesting primary elections.

Not that my Republican husband did much better in influencing his primary results than I did. And my most disappointing failures came in the school board elections, which are non-partisan anyway.

(Why should I, who have happily been out of the school business for a couple of decades now, and whose grandchildren live in another state/another county, care about the school board elections? If for no other reason, public education paid for by public taxes ought to be the concern of all the public, not just those who happen to have children in the schools.)

Am I willing to believe that a 25% non-random sample is sufficiently representative of eligible voters? Should I be happy about the results, on the (probably dubious) theory that those who took the trouble to vote are the better people? I don't think so.

Regardless, voting is the closest thing we have to a secular sacrament, and its neglect is nearly as disappointing as when Christians decide that that participating in the sacred sacraments is "nice, but not all that important."

If nothing else, folks, voting gives you a more legitimate right to complain about how badly things are being run. Who would turn down that opportunity?

Unoffendable: How Just One Change Can Make All of Life Better by Brant Hansen (W Publishing Group, 2015)

Unoffendable: How Just One Change Can Make All of Life Better by Brant Hansen (W Publishing Group, 2015)

This book was recommended by a dear friend who hadn't, at least at the time, read it herself. I reacted badly based on what I understood the idea of the book to be, and for my penance I had to read it.

It turned out to be both better and worse than I expected. The author's style is informal to the fingernails-on-the-blackboard level; it hardly sounds like book-writing at all. Perhaps it would work for a sermon, though even in sermons familiarity can get annoying. He also makes the mistake of thinking he knows what the reader is thinking and feeling, and at least in my case, he's very often wrong.

That said, I'm glad I read the book and I did find something of potentially great value.

The gut reaction that I needed to repent of was set up by a local billboard I'd seen repeatedly, which simply stated, "God is not angry." I couldn't drive by that without thinking, "If God is not angry about the inhumane (if not inhuman) things we do to each other, he's not much of a god." Granted, Brant Hansen is okay with God being angry about such things, but thinks such a reaction is above our human pay grade. Maybe he's right, but I do believe we share the responsibility of fighting against evil. I agree with this line from one of my favorite books, The Green Ember: "If you aren’t angry about the wicked things happening in the world all around, then you don’t have a soul."

It's on the personal level that Hansen's idea shines. In the first paragraph of the first chapter is this line:

You can choose to be "unoffendable."

I'm not sure which of my thoughts about this are from the book, and which are my own musings while reading it. But this is what I came up with.

There may be some debate about how we should respond when someone else is being wronged, but on a personal level, when I'm the victim, I can, indeed, choose not to be offended. I can take my hurt and anger and use them as an opportunity to practice one of the hardest and most important virtues in the Christian life: forgiveness. I can work to assume the person meant better than I think he did, that what I heard was not what she said, or meant to say. I can remember the times I've needed that grace myself.

Yes, we get angry. Can’t avoid it. But I now know that anger can’t live here. I can’t keep it. ... I have to take it to the Cracks of Doom, like, now, and drop that thing. (p. 21)

Yes, the world is broken. But don’t be offended by it. Instead, thank God that He’s intervened in it, and He’s going to restore it to everything it was meant to be. His kingdom is breaking through, bit by bit. Recognize it, and wonder at it.

War is not exceptional; peace is. Worry is not exceptional; trust is. Decay is not exceptional; restoration is. Anger is not exceptional; gratitude is. Selfishness is not exceptional; sacrifice is. Defensiveness is not exceptional; love is.

And judgmentalism is not exceptional...

But grace is.

Recognize our current state, and then replace the shock and anger with gratitude. Someone cuts you off on your commute? Just expect it. No big deal. Let it drop, and then be thankful for the person, that exceptional person, who lets you merge. See the human heart for what it is, adjust expectations, and be grateful, not angry. (pp. 40-41)

One thing that helped me get more from Unoffendable was changing some of his language. He focusses too much on anger, I think. Granted, I do have to deal at times with my own angry reactions, but by far the predominant emotion I associate with being offended is hurt.

No matter, really. If I can choose to set aside anger, I can do the same with hurt. I can't help being hurt, but I can control my reactions.

Easier said than done. But very liberating, whenever I can manage it, even on a very small scale.

I think we're being gaslighted.

How is it that we have come to a society where:

- If you hold conservative views, you are not really black, no matter how dark your skin or how purely African your ethnic origin.

- If you believe induced abortion is a procedure that takes the life of an innocent child and should be used only in the most extreme circumstances, you are not really a woman, no matter what your chromosomes might say. Indeed, you are less of a "woman" than a biological male who has had surgery and/or hormone treatments but professes the acceptable political beliefs.

- If you acknowledge your sexual and/or gender differences and choose to live a celibate life in acceptance of the body and mind with which you were born, you are not really LGBTetc.

- If you profess beliefs that were common among mainstream Democrats in the time of President Kennedy, you most definitely are not really a Democrat, no matter what it says on your voter registration card; you are more than likely to be considered a right-wing extremist.

- You may have graduated at the top of your class from the best medical school and had decades of wide-ranging medical experience, but if you question the lines drawn by the CDC, the AMA, the FDA, and I don't know maybe even the FBI and the SEC, you are not a real doctor, and what's more you are a threat to society. You risk being ostracized, banned from social media, and having your career, your livelihood, and your medical licenses threatened.

- If you are a scientist, no matter how many PhD's, Nobel Prizes and other awards, research grants, published papers, and other accomplishments you have accumulated, if at some point your work produces results not in line with the currently-fashionable scientific thoughts, you are ignorant, dangerous, and not a real scientist. You will find it difficult to impossible to get your work published in reputable, mainstream scientific publications, and will be in a similar position to the doctors who challenge the established canon. Of course, this is actually the way science and medicine commonly work, and true to history: real breakthroughs in understanding are often made by those whose life and work are rejected by the powers-that-be.

- And the list goes on.

Welcome to the world of modern phrenology. Instead of believing we can know a person's character and mental abilities by examining the bumps on his head, we presume to do the same based on equally absurd characteristics.

That's crazy. Worse, it's rude.

.jpg)