A brand-new story is on its way from S. D. Smith, creator of the Green Ember series. There's a trailer at JackZulu.com, and I'm sure more information will follow.

In the meantime, two of the Green Ember books are currently free for Kindle, with more to come next week. But really, the regular Kindle prices are so low, it's not worth stressing of you miss the sales.

In my review of Michael Pollan's book, Cooked, I noted what a professional chef told him about using salt.

"Use at least three times as much salt as you think you should," she advised. (A second authority I consulted employed the same formulation, but upped the factor to five.) Like many chefs, Samin believes that knowing how to salt food properly is the very essence of cooking, and that amateurs like me approach the saltbox far too timorously. ...

Samin prefaced her defense of the practice by pointing out that the salt we add to our food represents a tiny fraction of the salt people get from their diet. Most of the salt we eat comes from processed foods, which account for 80 percent of the typical American's daily intake of sodium. "So, if you don't eat a lot of processed foods, you don't need to worry about it. Which means: Don't ever be afraid of salt!"

Clearly, chef Gordon Ramsay agrees. Spend three minutes watching this video of him demonstrating how to make the "perfect burger" at home, and you'll see him seasoning the creation—adding salt and pepper in generous quantities—seven separate times:

- burger side 1

- onions

- burger side 2

- burger again

- cheese 1

- cheese 2

- lettuce

After assembling the burger he finishes it with one more healthy dose of pepper.

If you're wondering why it is that hamburgers from your favorite restaurant taste so good, take note, and see if using a freer hand with seasoning makes a difference to your home cooking.

What I still don't understand, however, is how one eats such a creation. It looks fantastic, but who has a mouth that can get around such a thing? We're not snakes! That's my problem with restaurant burgers, which taste so good but which I can't manage to eat without requiring a fork to clean up everything that oozes out the sides, followed by a large stack of paper napkins and/or a trip to the restroom to wash my hands. Any suggestions?

The Real Anthony Fauci: Bill Gates, Big Pharma, and the Global War on Democracy and Public Health by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. (Skyhorse Publishing, 2021)

The Real Anthony Fauci: Bill Gates, Big Pharma, and the Global War on Democracy and Public Health by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. (Skyhorse Publishing, 2021)

As a teenager, I flirted with the Kennedy adulation so common among my peers. I was too young to know much about John F. Kennedy, though I vivdly remember proudly carrying a note from my mother explaining that I was late coming back to school from lunch because I had been watching Kennedy's inauguration on television. (We walked home from school for lunch every day; to some people, that probably makes me seem old enough for it to have been George Washington's inauguration—were it not for the television reference.) I barely even remember JFK's assassination, since I was at the eye doctor's at the time and thus missed the reactions of my classmates. However, I spent hours glued to the television during Robert F. Kennedy's funeral in 1968, and genuinely grieved. But that was then; the subsequent years gradually took the shine off both the Democratic Party and the Kennedy family for me. Our two years of living in the Boston area and hearing from the common people their stories of oppression at the hands of Kennedys sealed the deal.

So why would I choose to read a book by Robert F. Kennedy's own son and namesake? Why would I wade through a book that castigates Republicans and has nothing but admiration for his famous family? Why would I spend my two weeks at the beach reading a book of nearly 1000 pages without even the excuse of it being a Brandon Sanderson novel? (There's a confusing difference in number of pages between the Kindle version and the hardcover, with the former being nearly twice the latter. Whatever—it's long.)

Two reasons, maybe. It was recommended by someone whose opinions I respect, and although the book costs $20 in hardcover, it is only $2.99 in Kindle form.

I'll state upfront that the book is controversial. My first reaction was, "If this is true, why is Dr. Fauci not in jail? If it's not true, why isn't he suing Kennedy for libel?" Speaking of libel, feel free to read Kennedy's Wikipedia entry, which is a pretty good example of the way controversial topics are handled these days. You don't like what someone says? Why bother to refute his arguments when you can brand him a conspiracy theorist, a purveyor of false information, and shut him down? But go ahead, read the accusations. Then read the book.

Despite the seriousness of the subject, it is somewhat amusing and even encouraging to find a die-hard Democrat who is willing to skewer not just Republicans but much of his own party as well (though not the Kennedys themselves), while admitting that the hated Republicans have sometimes been closer to the truth, and revealing that presidents of both parties have been helpless in the hands of the bureaucrats whom they have been forced to trust.

Don't let the number of pages in this book dissuade you. Reading it went surprisingly quickly, not only because it is interesting, but because so much of it is pages and pages and pages of footnotes. If it's misinformation, it's certainly well-documented misinformation.

It did take me a while to get into the book. The first section, which is about COVID-19, is over-long and harder to read than the rest of the book. Perhaps because this problem is new and ongoing, Kennedy is not at his best, sometimes overly polemic. He's still angry in the rest of the book, but handles it better. Maybe I just got used to it. Or maybe I got angry, myself.

This is not a book to take my word for. Much of its value comes in its extensive documentation, its references and endnotes—not that you need to read them all, even if you could, but that you need to know the documentation is there. Kennedy is not just some politician spouting off his baseless opinions. In addition, he makes an effort to update both information and references online.

I will not provide here my usual selection of quotations. (That's not to say I won't produce a few in subsequent posts.) Instead you get my own very brief and inadequate summary, the table of contents, and a subset of the questions swirling in my mind—some I have been asking for decades, others generated through reading The Real Anthony Fauci.

The Précis

The health and safety of America's people, along with that of much of the rest of the world, has for decades been held hostage by the iron grip of an unholy alliance among the federal agencies charged with that responsibility, the pharmaceutical industry, our research universities, a few quasi-charitable organizations (such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation), and—come late to the table but enormously powerful—the gate-keepers of information (from CNN to Google). There's no reason to call it a conspiracy; "cartel" and "oligarchy" are the words that spring more readily to mind. The combination of good intentions (to put the best face on it), a great deal of hubris, and the power to acquire and control unimaginably vast sums of money qualifies as a man-made disaster of the highest magnitude. During my five-year tenure as a researcher at a major university medical center, I saw only the tiniest slice of the world of government grants and the network that controls academic publishing, but it was quite enough to make Kennedy's revelations believable.

The Contents

- Mismanaging a Pandemic

- Arbitrary Decrees: Science-Free Medicine

- Killing Hydroxychloroquine

- Ivermectin

- Remdesivir

- Final Solution: Vaccines or Bust

- Pharma Profits over Public Health

- The HIV Pandemic Template for Pharma Profiteering

- The Pandemic Template: AIDS and AZT

- The HIV Heresies

- Burning the HIV Heretics

- Dr. Fauci, Mr. Hyde: NIAID's Barbaric and Illegal Experiments on Children

- White Mischief: Dr. Fauci's African Atrocities

- The White Man's Burden

- More Harm Than Good

- Hyping Phony Epidemics: "Crying Wolf"

- Germ Games

The Questions

- Why has there been so little attention given to discerning why disorders such as autism, ADHD, asthma and other autoimmune diseases, allergies, and a variety of mental health issues have become so rampant?

- Why are we more concerned with selling highly profitable drug treatments and permanent surgical alterations instead of asking ourselves what might be in our water, our air, our food, our medical treatments, or our society that has caused so many boys to decide they need to be girls, and vice versa?

- Why do we quietly accept the marked deterioration in the health of our people after over a century of astonishing improvement?

- Why are those in our federal government who hold the solemn duty of safeguarding the nation's health allowed to reap huge personal profits (or any profit at all, for that matter) from vaccines and other products of the pharmaceutical industry? How is it not an infernal conflict of interest that the authorities responsible for declaring a new drug "safe and effective" stand to make a great deal of money if they give it their stamp of approval?

- Why was so much effort—and an unimaginable amount of money and other resources—put into developing and distributing COVID-19 vaccines, while the most obvious and most important question was ignored: How do we treat this disease?

- In the early months of the pandemic, boots-on-the-ground physicians successfully treated COVID-19 patients by repurposing inexpensive, already-approved drugs. Why were these doctors first ignored, then demonized, and their remedies (legal, with a long record of safety) pulled off the market by underhanded means?

- Why did we repeat with COVID-19 so many of the mistakes we made when struggling with AIDS in the 1980's?

- Why was the AIDS picture so different between America and Africa?

- Why are pharmaceutical companies, and charities such as the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation, allowed to dump on Africa, at significant profit, drugs and vaccines that have been deemed too dangerous for Americans?

- Why does much of our drug and vaccine testing take place in Africa, where the rules of proper research, record keeping, and informed consent can be ignored, and adverse events conveniently buried?

- Malaria used to be prevalent in the United States. Why has so much effort been spent on developing a still-mostly-ineffective malaria vaccine and so little on simple public health measures that might help eradicate it in Africa?

- Why has the United States government been sponsoring the development of biological warfare agents, through a loophole in international treaties?

- Why is our government outsourcing this biological warfare work to China, where regulations are lax and procedures known to be sloppy? Not to mention that China is known for industrial espionage and theft of intellectual property. Whoever imagined that it might be a good thing to avoid America's rules of legitimate research procedures while in all likelihood handing deadly technology over to a powerful country with whom our relations are uncertain at best?

- Why have we allowed our medical institutions and research universities to become so completely dependent on federal and industrial funding that their work is controlled and compromised?

- Why and when did we give up on the practice of scientific inquiry that has served so well in the past, and enshrine Science as a religion, wherein disagreement and debate, once necessary to the process, have become unspeakable heresy?

- Why did our COVID response appear to be so experimental and bumbling at the start—I remember saying, "Give them a break; they are doing the best they can with too little data"—when the strategies the government employed had actually been designed, simulated, planned for, and practiced for years, through multiple presidencies?

- And perhaps the most important question of all: Qui bono? How did the COVID-19 pandemic become the vehicle for a record transfer of wealth to the super-rich? Follow the money. Power corrupts; power over money corrupts exponentially.

There's more. Much more. Considering what Kennedy has discovered, the book turns out to be far more logical, documented, and measured than one has a right to expect. It's not everyone who can report rationally on something so shocking. This would be me:

Whatever your party affiliation or lack thereof, you owe it to yourself (and if you have children, especially to them) to invest $2.99 and a few hours in The Real Anthony Fauci. I'm at a loss as to how to confront the problems it reveals, but shedding some ignorance and blind trust is a start.

Turns out I'm admiring a Kennedy again. It only took me half a century.

Permalink | Read 1836 times | Comments (2)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Shame on us, Florida!

A 25% voter turn-out? Are you kidding me?

I'll admit that I wasn't thrilled by yesterday's primary election. The Democratic canditates were for the most part so disappointing I often found it hard to figure out the "least worst." This life-long Democrat has begun contemplating more seriously the idea of switching parties, just to be able to vote in the more interesting primary elections.

Not that my Republican husband did much better in influencing his primary results than I did. And my most disappointing failures came in the school board elections, which are non-partisan anyway.

(Why should I, who have happily been out of the school business for a couple of decades now, and whose grandchildren live in another state/another county, care about the school board elections? If for no other reason, public education paid for by public taxes ought to be the concern of all the public, not just those who happen to have children in the schools.)

Am I willing to believe that a 25% non-random sample is sufficiently representative of eligible voters? Should I be happy about the results, on the (probably dubious) theory that those who took the trouble to vote are the better people? I don't think so.

Regardless, voting is the closest thing we have to a secular sacrament, and its neglect is nearly as disappointing as when Christians decide that that participating in the sacred sacraments is "nice, but not all that important."

If nothing else, folks, voting gives you a more legitimate right to complain about how badly things are being run. Who would turn down that opportunity?

Unoffendable: How Just One Change Can Make All of Life Better by Brant Hansen (W Publishing Group, 2015)

Unoffendable: How Just One Change Can Make All of Life Better by Brant Hansen (W Publishing Group, 2015)

This book was recommended by a dear friend who hadn't, at least at the time, read it herself. I reacted badly based on what I understood the idea of the book to be, and for my penance I had to read it.

It turned out to be both better and worse than I expected. The author's style is informal to the fingernails-on-the-blackboard level; it hardly sounds like book-writing at all. Perhaps it would work for a sermon, though even in sermons familiarity can get annoying. He also makes the mistake of thinking he knows what the reader is thinking and feeling, and at least in my case, he's very often wrong.

That said, I'm glad I read the book and I did find something of potentially great value.

The gut reaction that I needed to repent of was set up by a local billboard I'd seen repeatedly, which simply stated, "God is not angry." I couldn't drive by that without thinking, "If God is not angry about the inhumane (if not inhuman) things we do to each other, he's not much of a god." Granted, Brant Hansen is okay with God being angry about such things, but thinks such a reaction is above our human pay grade. Maybe he's right, but I do believe we share the responsibility of fighting against evil. I agree with this line from one of my favorite books, The Green Ember: "If you aren’t angry about the wicked things happening in the world all around, then you don’t have a soul."

It's on the personal level that Hansen's idea shines. In the first paragraph of the first chapter is this line:

You can choose to be "unoffendable."

I'm not sure which of my thoughts about this are from the book, and which are my own musings while reading it. But this is what I came up with.

There may be some debate about how we should respond when someone else is being wronged, but on a personal level, when I'm the victim, I can, indeed, choose not to be offended. I can take my hurt and anger and use them as an opportunity to practice one of the hardest and most important virtues in the Christian life: forgiveness. I can work to assume the person meant better than I think he did, that what I heard was not what she said, or meant to say. I can remember the times I've needed that grace myself.

Yes, we get angry. Can’t avoid it. But I now know that anger can’t live here. I can’t keep it. ... I have to take it to the Cracks of Doom, like, now, and drop that thing. (p. 21)

Yes, the world is broken. But don’t be offended by it. Instead, thank God that He’s intervened in it, and He’s going to restore it to everything it was meant to be. His kingdom is breaking through, bit by bit. Recognize it, and wonder at it.

War is not exceptional; peace is. Worry is not exceptional; trust is. Decay is not exceptional; restoration is. Anger is not exceptional; gratitude is. Selfishness is not exceptional; sacrifice is. Defensiveness is not exceptional; love is.

And judgmentalism is not exceptional...

But grace is.

Recognize our current state, and then replace the shock and anger with gratitude. Someone cuts you off on your commute? Just expect it. No big deal. Let it drop, and then be thankful for the person, that exceptional person, who lets you merge. See the human heart for what it is, adjust expectations, and be grateful, not angry. (pp. 40-41)

One thing that helped me get more from Unoffendable was changing some of his language. He focusses too much on anger, I think. Granted, I do have to deal at times with my own angry reactions, but by far the predominant emotion I associate with being offended is hurt.

No matter, really. If I can choose to set aside anger, I can do the same with hurt. I can't help being hurt, but I can control my reactions.

Easier said than done. But very liberating, whenever I can manage it, even on a very small scale.

I think we're being gaslighted.

How is it that we have come to a society where:

- If you hold conservative views, you are not really black, no matter how dark your skin or how purely African your ethnic origin.

- If you believe induced abortion is a procedure that takes the life of an innocent child and should be used only in the most extreme circumstances, you are not really a woman, no matter what your chromosomes might say. Indeed, you are less of a "woman" than a biological male who has had surgery and/or hormone treatments but professes the acceptable political beliefs.

- If you acknowledge your sexual and/or gender differences and choose to live a celibate life in acceptance of the body and mind with which you were born, you are not really LGBTetc.

- If you profess beliefs that were common among mainstream Democrats in the time of President Kennedy, you most definitely are not really a Democrat, no matter what it says on your voter registration card; you are more than likely to be considered a right-wing extremist.

- You may have graduated at the top of your class from the best medical school and had decades of wide-ranging medical experience, but if you question the lines drawn by the CDC, the AMA, the FDA, and I don't know maybe even the FBI and the SEC, you are not a real doctor, and what's more you are a threat to society. You risk being ostracized, banned from social media, and having your career, your livelihood, and your medical licenses threatened.

- If you are a scientist, no matter how many PhD's, Nobel Prizes and other awards, research grants, published papers, and other accomplishments you have accumulated, if at some point your work produces results not in line with the currently-fashionable scientific thoughts, you are ignorant, dangerous, and not a real scientist. You will find it difficult to impossible to get your work published in reputable, mainstream scientific publications, and will be in a similar position to the doctors who challenge the established canon. Of course, this is actually the way science and medicine commonly work, and true to history: real breakthroughs in understanding are often made by those whose life and work are rejected by the powers-that-be.

- And the list goes on.

Welcome to the world of modern phrenology. Instead of believing we can know a person's character and mental abilities by examining the bumps on his head, we presume to do the same based on equally absurd characteristics.

That's crazy. Worse, it's rude.

The only thing I don't like about McCormick's Peppercorn Medley Grinder is that it isn't refillable, which seems like such a waste.

The only thing I don't like about McCormick's Peppercorn Medley Grinder is that it isn't refillable, which seems like such a waste.

The flavor, however, is fantastic! In the past, I was a very modest pepper user; now I find myself grinding this on so many foods and in much greater quantity than before. It's that delicious.

This mix, which in our local Publix is found in the spice section with the pre-filled pepper and salt grinders, includes black peppercorns, coriander, pink peppercorns (which, I understand, aren't actually pepper), white peppercorns, allspice, and green peppercorns.

I highly recommend this spice blend to everyone, except my one friend who is allergic to pepper and my other friend who is allergic to coriander/cilantro. Everyone else—do give it a try.

It began a month ago, when we made the decision to switch our phones from AT&T to Spectrum. Spectrum is our cable internet provider, and now offers mobile phone service, which through some sleight of hand is actually Verizon.

We had been loyal AT&T customers all our long lives, from back when "Ma Bell" was the only way to go for long distance; through the forced breakup of AT&T that led to our move to Florida in the mid-1980's and Porter's 17 years of employment with the company; to our very first cell phone ("car phone") in the early 90's, and many changes of phones and phone service since—wherever we were, whatever our phones, it was all AT&T. I do know that there's really nothing left of the original AT&T besides the name, but still, it hurt to leave.

But recently we had two very annoying and expensive experiences with AT&T:

- "I don't care what the e-mail we sent you says, our system says differently so we're not going to honor the deal you signed up for."

- "Whatever made you think that making a call using Wi-fi Calling would not cost an arm and a leg when calling Switzerland?")

When these were quickly followed by

- A shockingly high price increase,

that was it for the camel's back. Spectrum/Verizon offered a price/service combination that was such an improvement we decided it was worth trying.

However, our AT&T root system was apparently stronger than we knew.

We made the account switch with ease, or so it seemed. When our new SIM cards arrived from Spectrum, Porter's phone made the switch without a hitch. My phone, on the other hand....

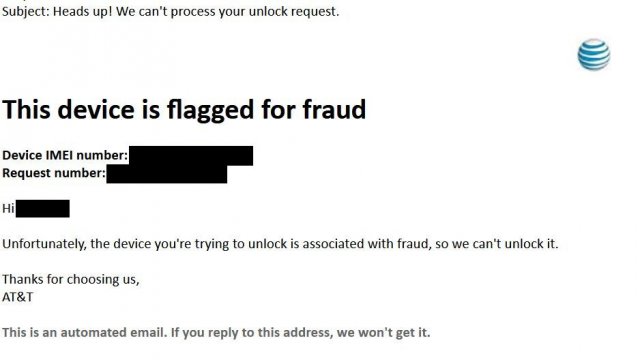

As I powered my phone back on after inserting the new SIM card, the phone insisted that I enter an unlock code. This was a bit concerning, as the phone was supposed to have been unlocked already. Thus began more than three weeks of struggle (mostly Porter's heroic work) with AT&T, Spectrum, and Samsung.

We tried multiple times to unlock the phone using AT&T's website. A few days after each try, we'd get an e-mail telling us there was a problem.

Next level: phone calls. Many phone calls, countless hours. Each time we'd be assured that an unlock code would come by e-mail "in a few days." Each time the result was failure.

By this time, we were on vacation in Connecticut, thankful to have one working phone as we continued the adventure. Hoping that being physically present might move things along, we took my phone to the local AT&T store. Although the sales clerk was friendly and tried to help, there wasn't much he could do as a simple reseller of AT&T services. So he sent us to a true AT&T store, half an hour down the road in Branford. As we drove along, we tried another phone call, ending up on hold for about an hour and a half in total, before giving up.

The Branford guy started our visit optimistically: "I can fix anything." Before we were done he'd gone so far as to drag the District Manager from another store out of a meeting to help. She was able to confirm that there was absolutely no reason we shouldn't be able to unlock the phone, and she said it shouldn't be necessary for us to drive to her store. We were grateful, as it was at that point rush hour, which in New Haven is nothing to be trifled with, and would have more than doubled the nominal 20-minute drive time. She escalated our problem up to highest priority, and we left the store armed with her telephone number.

Unfortunately, in the end, even that came to nothing. We went home to Florida.

Several more phone calls and no progress later, we learned that, while our problem was stilll "highest priority," it no longer had a person attached to it but had been kicked back to being assigned to a group. Knowing AT&T's trouble ticketing system from the inside out, Porter recognized this as the place insoluble problems are sent to die.

I'm half convinced the various companies hired someone's creative writing class to invent the reasons why they couldn't give me an unlock code.

- (AT&T) "Something went wrong, try again."

- (AT&T) "We can't give you a code because we can't get one from Samsung."

- (Samsung) "We can't give you a code because we don't do that; the code has to come from the carrier." (True, but it turns out that there is actually a code that must come from the manufacturer to the carrier, first.)

- (Samsung) "We can't give you a code because you bought the phone directly from us and all our phones ship unlocked already." (True, though it appears AT&T subsequently locked it, because we paid for it through our AT&T bill.)

- (AT&T) "We can't give you a code because your phone is already unlocked." (That's what their system kept telling them, but it was clearly untrue.)

- (Spectrum) "We can't help you because it was locked by AT&T."

- (AT&T) "Success! Here's your unlock code." That might have been encouraging, except that the code was simply "0." Right. An unconvincing null. With infinitesimal faith that it would work, we used up two of the five allowed attempts (after which the phone would become "permanantly locked") trying both a simple 0 and enough 0's to fill in the requested number of digits. As expected, it didn't work.

My all-time favorite of their excuses I reproduce below:

What on earth was the problem? We had bought the phone new, directly from Samsung, and it's hardly been out of my presence ever since. For a long time, this one had me looking over my shoulder for the FBI. Hey, if they can raid the private residence of a former U.S. president on the flimsiest of excuses, what chance do the rest of us have? Are they still mad about the grainy picture of Osama bin Laden that so annoyed Facebook?

After learning that there was little to no chance of our problem getting out of the trouble ticket graveyard, Porter employed a different tactic, one I would have given no chance at all of making any difference: He filed a complaint with the Federal Communications Commission.

Have you ever wondered if governmental agencies actually do anything to earn their tax dollars? In this case, Porter's complaint generated near-immediate action, first by the FCC itself and then by AT&T.

I'm not kidding: in a very short time he received both an e-mail and a phone call from the office of the president. (Of AT&T, that is, not Joe Biden.) A friendly and competent-sounding person promised to see what she could do.

At this point we began seriously debating how we would proceed if AT&T decided they were spending 'way too much money on this problem and offered to give us a new phone instead. It was not an easy decision. The lower-level folks who had no power to do so were, of course all in favor of giving away a phone. The mid-level folks grudgingly acknowledged that it might be a possibility, but only if I turned over my phone to them first. There was absolutely no way that was going to happen; my phone was not going to leave my possession until I had a working replacement with all my settings, apps, and data successfully transferred. Maybe they would be willing to send the new phone to our local AT&T store until we could successfully make the switch.

Then there was the problem of which phone? I didn't expect an upgrade to a more current phone: my Galaxy S9, even though it was the lastest thing in 2018, is now so old it's almost useless as a trade-in. I'd have been happy with a new S9, but do they even have any of those hanging around? Would I be offered a used, reconditioned phone, and would I be okay with that?

As it turned out, all that speculating was unnecessary. In only a few days, Porter received an e-mail with a non-zero unlock code.

Not without some trembling, we carefully, step by step, followed the instructions and entered the code into my mobile phone.

I have a working, Spectrum-serviced, cell phone.

A small part of me is reluctant to admit that. It was surprisingly easy to get along for nearly a month without one. Certainly it helped that I could do almost anything I wanted to with my phone, as long as I had wi-fi, which these days is nearly ubiquitous, even here.

I only missed a couple of things:

- The ability to make non-911 phone calls. (All phones work for emergencies, or so my phone told me.) If I were designing something named "Wi-Fi Calling," it would work using wi-fi when one does not have cell service. I mean, otherwise, what's the point? Especially if carriers are going to charge the same price as for regular cell calls (see above). But I wasn't the designer on that one. Even though I drove for decades without having cell service, I couldn't drive this past month without being aware of the lack.

- The ability to send and receive texts. That, too, should be possible over wi-fi.

Grateful as I am to have a fully-functioning phone, I have to say that a month without phone calls and texts was not all bad, It was rather nice, in fact—especially during political season.

Many thanks to all those ordinary people at AT&T and other places who were friendly and cheerful, and truly seemed to be doing what they could to help us. And deep gratitude to the one person at AT&T who somehow cut through the nonsense and got the job done. As Porter said in his thank you note to her, "If everyone at AT&T were as effective as you are, we'd still be customers."

I've written twice before about Jack Barsky, once in The Spy Who Stayed, and again when I reviewed his book, Deep Undercover. Barsky, once a brilliant East German student named Albert Dittrich, was recruited as a KGB spy, infiltrated American society, and ended up sending his daughter to the small, Christian school in upstate New York where my life-long friend had been principal for decades. That friend is the one who sent me this YouTube video, an interview with Barsky on the Lex Frieman Podcast.

Note that this interview is three and a half hours long. I don't have that kind of attention span for videos, not even for exciting movies. But we both wanted to watch ii, so we decided to make an event out of the process. We watched it together on the television, as if it were a movie, and spread it out over three days.

Actually, it was interesting enough to have done it over a shorter time period, but this turned out to be just about perfect for us. When we watch YouTube via Roku, we can't set it to 1.5x or 2x speed, which we prefer, but even though the pace was relaxed and unhurried, it was so interesting we never once missed the time compression.

This was my first experience with Lex Fridman's show, and I'm eager to see more. He and Barsky cover many topics as they explore Barsky's life, and it was a joy to see two such brilliant minds interacting. And in case you're wondering, my friend assures me that "It's definitely the real Jack" she knew.

Content warning for a couple of words, but I think our older grandchildren (who have heard much worse) might enjoy it. Or perhaps his book would be a better place to start. (See review link above.)

Permalink | Read 1098 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I took a COVID test this week.

I try to avoid those things as much as possible: I hadn't taken one since April, when I needed it to get back into the United States. But I picked up a mild cold in Connecticut, and as sometimes happens I have a cough that is still hanging on. I never seriously thought it might be COVID, especially since our grandson (who was hit harder than the rest of us), had tested negative.

However, I couldn't deny that the symptoms I experienced were exactly the same as when I genuinely had COVID-19, back in April. When I sing with them on Sunday, my fellow choir members will be happier if I can assure them that my cough is not due to the Dread Disease. So I took the test.

No surprises. It was negative.

Apparently, getting random colds is a thing again. I suppose we could go back to dropping all contact with the outside world—which gave us two years totally free of such annoyances. But I'm sure our immune systems are much better for the stimulation.

Thanksgiving has apparently come early to Florida.

We awoke to the news that Interstate 4 just north of us was shut down when a semi loaded with frozen turkeys caught fire. (You can see pictures at that link.)

According to news reports, no one was injured. Except the turkeys.

I've heard of some strange ways of cooking a Thanksgiving turkey, including smoking, deep-frying, and my brother-in-law's favorite turkey-in-the-trash-can method.

But roasting them in a tractor-trailer, followed by steaming after the fire department arrives? That's a new one.

Permalink | Read 904 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

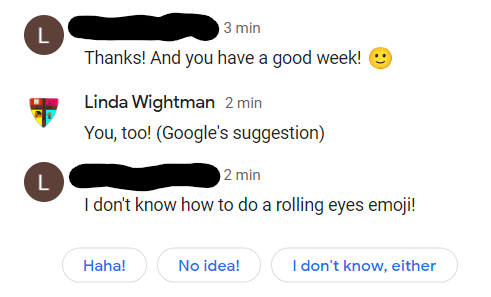

I didn't choose Google Chat.

I still have one friend with whom I communicate by what was once known as Instant Messaging. Over the years, we have periodically been forced to change IM clients, and we mostly just go with the flow. (It was one such change that required me to get a Gmail address, which I had been resisting.)

The most recent change came when Google announced that Hangouts was being phased out in favor of Google Chat. I didn't complain too much, because they clearly had not been supporting Hangouts for a while—it would routinely crash on me several times during a half-hour conversation.

But Google Chat is creepy. (Just one in a long line of new tech creepiness.) When my friend enters a line, Chat usually pops up suggested responses for me, clearly based on what my friend has just said—possibly even on an analysis of the whole conversation. And quite accurately, I might add. Perhaps worse than the eavesdropping itself is that on the recipient's end, there is no indication that I did not type the response myself.

Here's what it looks like. I added the "(Google's suggestion)" after clicking the "You, too!" button presented to me.

My friend's version of Chat (or maybe she's still on Hangouts) does not yet have this feature, but she says it happens on her phone when texting. In the future shall we stop thinking at all and just let the AI control the conversation? Perhaps if I were having this conversation on my phone I might appreciate these shortcuts more, since I loathe what passes for typing on the phone. But here on my computer I can type nearly as fast as I can speak, so I'd rather use my own words, thank you.

You know how after you've watched a video on YouTube, it goes on to show you some other video it thinks you might like? Usually it's off base, but the first video below so entranced me that I went on to watch the next two in the series. Erik Singer is a dialect coach, and his tour of accents across America is entertaining and fascinating. Even if he ignores most of Florida, and you have to endure some awkward and annoying "politically correct" speech along the way.

Part 1 (22 minutes)

Part 2 (14 minutes)

Part 3 (11 minutes)

Enjoy!

Permalink | Read 1059 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I have too many Kindle books.

Granted, 280+ is a drop in the bucket compared with the physical books that crowd our bookshelves. Many of the ebooks are duplicates of physical books I already have, books I value so much I want them in both forms so I can easily search and highlight. But many are unique, since I find it very hard to resist when eReaderIQ alerts me that a book I'm interested in is on sale for $2.99 in Kindle form. While I really love the feel (and often smell) of physical books, I also appreciate what ebooks have to offer.

What concerns me, when I say I have too many Kindle books, is that I've bought and paid for them, but they're not really mine. Amazon has the ability—and sadly the right—to reach down into my Kindle and take them away from me at any time. True, they're supposed to refund the purchase price if they do so, but that's absolutely not the point. This was a concern I had at the very beginning of my relationship with Kindle, when I read the Terms & Conditions. I conveniently shelved the worry as the years went by with no problems. However, in these days of repeated attacks on First Amentment freedom of speech, social media posts and whole accounts being deleted for no reason other than that the platform objects to the (legal, protected) content, and people living in fear of offending algorithms—well, you can imagine why paranoia has returned.

I'm not certain what to do about it, other than what I just did: order a physical book that I don't actually want, just because I can imagine its very important content offending the Powers That Be enough for Amazon to make it disappear. I guess I can call it a donation to the author.

Maybe I should reread Fahrenheit 451. While I still can.

I've been writing these essays for more than 20 years. As with all writers (and other artists), I often look back on my work and shudder. Sometimes, however, I'm okay with what I've written. But how often does someone see a blog post from 2010? Current events may not be relevant anymore and can reasonably be forgotten, and most people don't care about our everyday lives. But I've also said a lot that I think bears repeating; book reviews, for example, are almost always just as useful now as they were then. So I'm going to start to bring back some of my favorites, not only because I believe they'll be useful to what is mostly a whole new audience, but also because I need to be reminded of the content myself.

I'll begin with the fascinating, and important, idea of neuroplasticity, which I first wrote about on May 18, 2010.

The Brain that Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science by Norman Doidge (Penguin, New York, 2007)

The Brain that Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science by Norman Doidge (Penguin, New York, 2007)

Neuroplasticity.

The idea that our brains are fixed, hard-wired machines was (and in many cases still is) so deeply entrenched in the scientific establishment that evidence to the contrary was not only suppressed, but often not even seen because the minds of even respectable scientists could not absorb what they were certain was impossible. Having been familiar since the 1960s with the work of Glenn Doman and the Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential, the idea that the human brain is continually changing itself and can recover from injury in astonishing ways did not surprise me. In fact, the only shock was that in a 400 page book on neuroplasticity and the persecution of its early pioneers I found not one mention of Doman's name. But the stories are none the less astonishing for that.

In Chapter 1 we meet a woman whose vestibular system was destroyed by antibiotic side-effects. She is freed by a sensor held on her tongue and a computerized helmet from the severely disabling feeling that she is falling all the time, even when lying flat. That's the stuff of science fiction, but what's most astounding is that the effect lingers for a few minutes after she removes the apparatus the first time, and after several sessions she no longer needs the device.

Chapter 3, "Redesigning the Brain," on the work of Michael Merzenich, including the ground-breaking Fast ForWord learning program, is worth the cost of the book all by itself.

Sensitive readers may want to steer clear of Chapter 4, "Acquiring Tastes and Loves," or risk being left with unwanted, disturbing mental images. But it is a must read for anyone who wants to believe that pornography is harmless, or that our personal, private mental fantasies do not adversely affect the very structure of our brains.

The book is less impressive when it gets away from hard science and into psychotherapy, as the ideas become more speculative, but the stories are still impressive.

Phantom pain, learning disabilities, autism, stroke recovery, obsessions and compulsions, age-related mental decline, and much more: the discovery of neuroplasticity shatters misconceptions and offers hope. The Brain that Changes Itself is an appetizer plate; bring on the main course!

For those who want a sampling of the appetizer itself, I'm including an extensive quotation section. Even so, it doesn't come close to doing justice to the depth and especially the breadth of the book. I've pulled quotes from all over, so understand that they are out of context, and don't expect them to move smoothly from one section to another.

Neuro is for "neuron," the nerve cells in our brains and nervous systems. Plastic is for "changeable, malleable, modifiable." At first many of the scientists didn't dare use the word "neuroplasticity" in their publications, and their peers belittled them for promoting a fanciful notions. Yet they persisted, slowly overturning the doctrine of the unchanging brain. They showed that children are not always stuck with the mental abilities they are born with; that the damaged brain can often reorganize itself so that when one part fails, another can often substitute; that if brain cells die, they can at times be replaced; that many "circuits" and even basic reflexes that we think are hardwired are not. One of these scientists even showed that thinking, learning, and acting can turn our genes on or off, thus shaping our brain anatomy and our behavior—surely one of the most extraordinary discoveries of the twentieth century.

In the course of my travels I met a scientist who enabled people who had been blind since birth to begin to see, another who enabled the deaf to hear; I spoke with people who had had strokes decades before and had been declared incurable, who were helped to recover with neuroplastic treatments; I met people whose learning disorders were cured and whose IQs were raised; I saw evidence that it is possible for eighty-year-olds to sharpen their memories to function the way they did when they were fifty-five. I saw people rewire their brains with their thoughts, to cure previously incurable obsessions and traumas. I spoke with Nobel laureates who were hotly debating how we must re-think our model of the brain now that we know it is ever changing. ... The idea that the brain can change its own structure and function through thought and activity is, I believe, the most important alteration in our view of the brain since we first sketched out its basic anatomy and the workings of its basic component, the neuron.

In Chapter 2, Building Herself a Better Brain, a woman with such a severe imbalance of brain function that she was labelled mentally retarded put her own experiences together with the work of other researchers to design brain exercises that fixed the weaknesses in her own brain ... and went on to develop similar diagnostic procedures and exercises for others.

The irony of this new discovery is that for hundreds of years educators did seem to sense that children's brains had to be built up through exercises of increasing difficulty that strengthened brain functions. Up through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries a classical education often included rote memorization of long poems in foreign languages, which strengthened the auditory memory (hence thinking in language) and an almost fanatical attention to handwriting, which probably helped strengthen motor capacities and thus not only helped handwriting but added speed and fluency to reading and speaking. Often a great deal of attention was paid to exact elocution and to perfecting the pronunciation of words. Then in the 1960s educators dropped such traditional exercises from the curriculum, because they were too rigid, boring, and "not relevant." But the loss of these drills has been costly; they may have been the only opportunity that many students had to systematically exercise the brain function that gives us fluency and grace with symbols. For the rest of us, their disappearance may have contributed to the general decline of eloquence, which requires memory and a level of auditory brainpower unfamiliar to us now. In the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858 the debaters would comfortably speak for an hour or more without notes, in extended memorized paragraphs; today many of the most learned among us, raised in our most elite schools since the 1960s, prefer the omnipresent PowerPoint presentation—the ultimate compensation for a weak premotor cortex.

Here are several (but not enough!) from my favorite chapter, "Redesigning the Brain."

[As] they trained an animal at a skill, not only did its neurons fire faster, but because they were faster their signals were clearer. Faster neurons were more likely to fire in sync with each other—becoming better team players—wiring together more and forming groups of neurons that gave off clearer and more powerful signals. This is a crucial point, because a powerful signal has greater impact on the brain. When we want to remember something we have heard we must hear it clearly, because a memory can be only as clear as its original signal.

Paying close attention is essential to long-term plastic change. ... When the animals performed tasks automatically, without paying attention, they changed their brain maps, but the changes did not last. We often praise "the ability to multitask." While you can learn when you divide your attention, divided attention doesn't lead to abiding change in your brain maps.

Somewhere between 5 and 10 percent of preschool children have a language disability that makes it difficult for them to read, write, or even follow instructions. ... [C]hildren with language disabilities have auditory processing problems with common consonant-vowel combinations that are spoken quickly and are called "the fast parts of speech." The children have trouble hearing them accurately and, as a result, reproducing them accurately. Merzenich believed that these children's auditory cortex neurons were firing too slowly, so they couldn't distinguish between two very similar sounds or be certain, if two sounds occurred close together, which was first and which was second. Often they didn't hear the beginnings of syllables or the sound changes within syllables. Normally neurons, after they have processed a sound, are ready to fire again after about a 30-millisecond rest. Eighty percent of language-impaired children took at least three times that long, so that they lost large amounts of language information. When their neuron-firing patterns were examined, the signals weren't clear. ... Improper hearing lead to weaknesses in all the language tasks, so they were weak in vocabulary, comprehension, speech, reading, and writing. Because they spent so much energy decoding words, they tended to use shorter sentences and failed to exercise their memory for longer sentences.

[Five hundred children at 35 sites] were given standardized language tests before and after Fast ForWord training. The study showed that most children's ability to understand language normalized after Fast ForWord. In many cases, their comprehension rose above normal. The average child who took the program moved ahead 1.8 years of language development in six weeks. ... A Stanford group did brain scans of twenty dyslexic children, before and after Fast ForWord. The opening scans showed that the children used different parts of their brains for reading than normal children do. After Fast ForWord new scans showed that their brains had begun to normalize.

Merzenich's team started hearing that Fast ForWord was having a number of spillover effects. Children's handwriting improved. Parents reported that many of the students were starting to show sustained attention and focus. Merzenich thought these surprising benefits were occurring because Fast ForWord led to some general improvements in mental processing.

"You know," [Merzenich] says, "IQ goes up. We used the matrix test, which is a visual-based measurement of IQ—and IQ goes up."

The fact that a visual component of the IQ went up meant that the IQ improvements were not caused simply because Fast ForWord improved the children's ability to read verbal test questions. Their mental processing was being improved in a general way.

This is just a sample of the benefits that made me want to rush right out and buy Fast ForWord, even if it were to cost as much as the insanely-expensive Rosetta Stone German software I'm also tempted to buy. From the description, it sounds like something everyone could benefit from for mental tune-ups. Unfortunately, the makers of Fast ForWord are even worse than the Rosetta Stone folks about keeping tight control over their product: as far as I've been able to determine, you can only use it under the direction of a therapist (making it too expensive for ordinary use), and even then you don't own the software but are only licensed to use it for a short period of time. :( It works, though. We know someone for whom it made all the difference in the world, even late in her school career.

Merzenich began wondering about the role of a new environmental risk factor that might affect everyone but have a more damaging effect on genetically predisposed children: the continuous background noise from machines, sometimes called white noise. White noise consists of many frequencies and is very stimulating to the auditory cortex.

"Infants are reared in continuously more noisy environments. There is always a din," he says. White noise is everywhere now, coming from fans in our electronics, air conditioners, heaters, and car engines.

To test this hypothesis, his group exposed rat pups to pulses of white noise throughout their critical period and found that the pups' cortices were devastated.

Psychologically, middle age is often an appealing time because, all else being equal, it can be a relatively placid period compared with what has come before. ... We still regard ourselves as active, but we have a tendency to deceive ourselves into thinking that we are learning as we were before. We rarely engage in tasks in which we must focus our attention as closely as we did when we were younger. Such activities as reading the newspaper, practicing a profession of many years, and speaking our own language are mostly the replay of mastered skills, not learning. By the time we hit our seventies, we may not have systematically engaged the systems in the brain that regulate plasticity for fifty years.

That's why learning a new language in old age is so good for improving and maintaining the memory generally. Because it requires intense focus, studying a new language turns on the control system for plasticity and keeps it in good shape for laying down sharp memories of all kinds. No doubt Fast ForWord is responsible for so many general improvements in thinking, in part because it stimulates the control system for plasticity to keep up its production of acetylcholine and dopamine. Anything that requires highly focused attention will help that system—learning new physical activities that require concentration, solving challenging puzzles, or making a career change that requires that you master new skills and material. Merzenich himself is an advocate of learning a new language in old age. "You will gradually sharpen everything up again and that will be very highly beneficial to you."

The same applies to mobility. Just doing the dances you learned years ago won't help your brain's motor cortex stay in shape. To keep the mind alive requires learning something truly new with intense focus. That is what will allow you to both lay down new memories and have a system that can easily access and preserve the older ones.

This work opens up the possibility of high-speed learning later in life. The nucleus basalis [always on for young children, but in adulthood only with sustained, close attention] could be turned on by an electrode, by microinjections of certain chemicals, or by drugs. It is hard to imagine that people will not ... be drawn to a technology that would make it relatively effortless to master the facts of science, history, or a profession, merely by being exposed to them briefly. ... Such techniques would no doubt be used by high school and university students in their studies and in competitive entrance exams. (Already many students who do not have attention deficit disorder use stimulants to study.) Of course, such aggressive interventions might have unanticipated, adverse effects on the brain—not to mention our ability to discipline ourselves—but they would likely be pioneered in cases of dire medical need, where people are willing to take the risk. Turning on the nucleus basalis might help brain-injured patients, so many of whom cannot relearn the lost functions of reading, writing, speaking, or walking because they can't pay close enough attention.

[Gross motor control is] a function that declines as we age, leading to loss of balance, the tendency to fall, and difficulties with mobility. Aside from the failure of vestibular processing, this decline is caused by the decrease in sensory feedback from our feet. According to Merzenich, shoes, worn for decades, limit the sensory feedback from our feet to our brain. If we went barefoot, our brains would receive many different kinds of input as we went over uneven surfaces. Shoes are a relatively flat platform that spreads out the stimuli, and the surfaces we walk on are increasingly artificial and perfectly flat. This leads us to dedifferentiate the maps for the soles of our feet and limit how touch guides our foot control. Then we may start to use canes, walkers, or crutches or rely on other senses to steady ourselves. By resorting to these compensations instead of exercising our failing brain systems, we hasten their decline.

As we age, we want to look down at our feet while walking down stairs or on slightly challenging terrain, because we're not getting much information from our feet. As Merzenich escorted his mother-in-law down the stairs of the villa, he urged her to stop looking down and start feeling her way, so that she would maintain, and develop, the sensory map for her foot, rather than letting it waste away.

Brain plasticity and psychological disorders:

Each time [people with obsessive-compulsive disorder] try to shift gears, they begin ... growing new circuits and altering the caudate. By refocusing the patient is learning not to get sucked in by the content of an obsession but to work around it. I suggest to my patients that they think of the use-it-or-lose-it principle. Each moment they spend thinking of the symptom ... they deepen the obsessive circuit. By bypassing it, they are on the road to losing it. With obsessions and compulsions, the more you do it, the more you want to do it; the less you do it, the less you want to do it ... [I]t is not what you feel while applying the technique that counts, it is what you do. "The struggle is not to make the feeling go away; the struggle is not to give in to the feeling"—by acting out a compulsion, or thinking about the obsession. This technique won't give immediate relief because lasting neuroplastic change takes time, but it does lay the groundwork for change by exercising the brain in a new way. ... The goal is to "change the channel" to some new activity for fifteen to thirty minutes when one has an OCD symptom. (If one can't resist that long, any time spent resisting is beneficial, even if it is only for a minute. That resistance, that effort, is what appears to lay down new circuits.)

Mental practice with physical results:

Pascual-Leone taught two groups of people, who had never studied piano, a sequence of notes, showing them which fingers to move and letting them hear the notes as they were played. Then members of one group, the "mental practice" group, sat in front of an electric piano keyboard, two hours a day, for five days, and imagined both playing the sequence and hearing it played. A second "physical practice" group actually played the music two hours a day for five days. Both groups had their brains mapped before the experiment, each day during it, and afterward. Then both groups were asked to play the sequence, and a computer measured the accuracy of their performances.

Pascual-Leoone found that both groups learned to play the sequence, and both showed similar brain map changes. Remarkably, mental practice alone produced the same physical changes in the motor system as actually playing the piece. By the end of the fifth day, the changes in motor signals to the muscles were the same in both groups, and the imagining players were as accurate as the actual players were on their third day.

The level of improvement at five days in the mental practice group, however substantial, was not as great as in those who did physical practice. But when the mental practice group finished its mental training and was given a single two-hour physical practice session, its overall performance improved to the level of the physical practice group's performance at five days. Clearly mental practice is an effective way to prepare for learning a physical skill with minimal physical practice.

In an experiment that is as hard to believe as it is simple, Drs. Guang Yue and Kelly Cole showed that imagining one is using one's muscles actually strengthens them. The study looked at two groups, one that did physical exercise and one that imagined doing exercise. ... At the end of the study the subjects who had done physical exercise increased their muscular strength by 30 percent, as one might expect. Those who only imagined doing the exercise, for the same period, increased their muscle strength by 22 percent. The explanation lies in the motor neurons of the brain that "program" movements. During these imaginary contractions, the neurons responsible for stringing together sequences of instructions for movements are activated and strengthened, resulting in increased strength when the muscles are contracted.

Talk about unbelievable.

The Sea Gypsies are nomadic people who live in a cluster of tropical islands in the Burmese archipelago and off the west coast of Thailand. A wandering water tribe, they learn to swim before they learn to walk and live over half their lives in boats on the open sea. ... Their children dive down, often thirty feet beneath the water's surface, and pluck up their food ... and have done so for centuries. By learning to lower their heart rate, they can stay under water twice as long as most swimmers. They do this without any diving equipment.

But what distinguishes these children, for our purposes, is that they can see clearly at these great depths, without goggles. Most human beings cannot see clearly under water because as sunlight passes through water, it is bent ... so that light doesn't land where it should on the retina.

Anna Gislén, a Swedish researcher, studied the Sea Gypsies' ability to read placards under water and found that they were more than twice as skillful as European children. The Gypsies learned to control the shape of their lenses and, more significantly, to control the size of their pupils, constricting them 22 percent. This is a remarkable finding, because human pupils reflexively get larger under water, and pupil adjustment has been thought to be a fixed, innate reflex, controlled by the brain and nervous system.

This ability of the Sea Gypsies to see under water isn't the product of a unique genetic endowment. Gislén has since taught Swedish children to constrict their pupils to see under water.

The fact that cultures differ in perception is not proof that one perceptual act is a good as the next, or that "everything is relative" when it comes to perception. Clearly some contexts call for a more narrow angle of view, and some for more wide-angle, holistic perception. The Sea Gypsies have survived using a combination of their experience of the sea and holistic perception. So attuned are they to the moods of the sea that when the tsunami of December 26, 2004, hit the Indian Ocean, killing hundreds of thousands, they all survived. They saw that the sea had begun to recede in a strange way, and this drawing back was followed by an unusually small wave; they saw dolphins begin to swim for deeper water, while the elephants started stampeding to higher ground, and they heard the cicadas fall silent. ... Long before modern science put this all together, they had either fled the sea to the shore, seeking the highest ground, or gone into very deep waters, where they also survived.

Music makes extraordinary demands on the brain. A pianist performing the eleventh variation of the Sixth Paganini etude by Franz Liszt must play a staggering eighteen hundred notes per minute. Studies by Taub and others of musicians who play stringed instruments have shown that the more these musicians practice, the larger the brain maps for their active left hands become, and the neurons and maps that respond to string timbres increase; in trumpeters the neurons and maps that respond to "brassy" sounds enlarge. Brain imaging shows that musicians have several areas of their brains—the motor cortex and the cerebellum, among others—that differ from those of nonmusicians. Imaging also shows that musicians who begin playing before the age of seven have larger brain areas connecting the two hemispheres.

It is not just "highly cultured" activities that rewire the brain. Brain scans of London taxi drivers show that the more years a cabbie spends navigating London streets, the larger the volume of his hippocampus, that part of the brain that stores spatial representations. Even leisure activities change our brain; meditators and meditation teachers have a thicker insula, a part of the cortex activated by paying close attention.

Here's something completely different, and frightening.

[T]otalitarian regimes seem to have an intuitive awareness that it becomes hard for people to change after a certain age, which is why so much effort is made to indoctrinate the young from an early age. For instance, North Korea, the most thoroughgoing totalitarian regime in existence, places children in school from ages two and a half to four years; they spend almost every waking hour being immersed in a cult of adoration for dictator Kim Jong Il and his father, Kim Il Sung. They can see their parents only on weekends. Practically every story read to them is about the leader. Forty percent of the primary school textbooks are devoted wholly to describing the two Kims. This continues all the way through school. Hatred of the enemy is drilled in with massed practice as well, so that a brain circuit forms linking the perception of "the enemy" with negative emotions automatically. A typical math quiz asks, "Three soldiers from the Korean People's Army killed thirty American soldiers. How many American soldiers were killed by each of them, if they all killed an equal number of enemy soldiers?" Such perceptual emotional networks, once established in an indoctrinated people, do not lead only to mere "differences of opinion" between them and their adversaries, but to plasticity-based anatomical differences, which are much harder to bridge or overcome than ordinary persuasion.

Think the North Koreans are the only ones whose brains are being re-programed?

"The Internet is just one of those things that contemporary humans can spend millions of 'practice' events at, that the average human a thousand years ago had absolutely no exposure to. Our brains are massively remodeled by this exposure—but so, too, by reading, by television, by video games, by modern electronics, by contemporary music, by contemporary 'tools,' etc." — Michael Merzenich, 2005

Erica Michael and Marcel Just of Carnegie Mellon University did a brain scan study to test whether the medium is indeed the message. They showed that different brain areas are involved in hearing speech and reading it, and different comprehension centers in hearing words and reading them. As Just put it, "The brain constructs the message ... differently for reading and listening. ... Listening to an audio book leaves a different set of memories than reading does. A newscast heard on the radio is processed differently from the same words read in a newspaper." This finding refutes the conventional theory of comprehension, which argues that a single center in the brain understands words, and it doesn't really matter how ... information enters the brain.

Television, music videos, and video games, all of which use television techniques, unfold at a much faster pace than real life, and they are getting faster, which causes people to develop an increased appetite for high-speed transitions in those media. It is the form of the television medium—cuts, edits, zooms, pans, and sudden noises—that alters the brain, by activating what Pavlov called the "orienting response," which occurs whenever we sense a sudden change in the world around us, especially a sudden movement. We instinctively interrupt whatever we are doing to turn, pay attention, and get our bearings. ... Television triggers this response at a far more rapid rate than we experience it in life, which is why we can't keep our eyes off the TV screen, even in the middle of an intimate conversation, and why people watch TV a lot longer than they intend. Because typical music videos, action sequences, and commercials trigger orientating responses at a rate of one per second, watching them puts us into continuous orienting response with no recovery. No wonder people report feeling drained from watching TV. Yet we acquire a taste for it and find slower changes boring. The cost is that such activities as reading, complex conversation, and listening to lectures become more difficult.

All electronic devices rewire the brain. People who write on a computer are often at a loss when they have to write by hand or dictate, because their brains are not wired to translate thoughts into cursive writing or speech at high speed. When computers crash and people have mini-nervous breakdowns, there is more than a little truth in their cry, "I feel like I've lost my mind!" As we use an electronic medium, our nervous system extends outward, and the medium extends inward.

Ouch!

"Use it or lose it" is a common refrain in The Brain that Changes Itself, whether talking about specific knowledge and abilities, or the capacity for learning and the very plasticity of the brain itself. (There is some hope given, however, that knowledge apparently lost is recoverable, even if its brain "map" has subsequently been taken over for another use.) Do you worry, as I did, that these new discoveries mean that it really is possible to learn too much, that we need to save our brains for that which is most important? That learning German will drive away what little I know of French? Relax; that doesn't need to happen, although I must be sure to keep the French fresh in my mind or it will get shelved.

As the scientist Gerald Edelman has pointed out, the human cortex alone has 30 billion neurons and is capable of making 1 million billion synaptic connections. Edelman writes, "If we considered the number of possible neural circuits, we would be dealing with hyper-astronomical numbers: 10 followed by at least a million zeros. (There are 10 followed by 79 zeros, give or take a few, of particles in the known universe.)" These staggering numbers explain why the human brain can be described as the most complex known object in the universe, and why it is capable of ongoing, massive microstructural change, and capable of performing so many different mental functions and behaviors.

I'm tired of typing. Get the book.

Permalink | Read 1218 times | Comments (1)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

.jpg)