As part of my ongoing project to organize and pare down my files (physical and digital) to something understandable to someone other than me (i.e. my heirs), I've been coming across many interesting glimpses of history. I try not to read more than a very small fraction of these, for the sake of making progress, but every once in a while something catches my eye.

We discovered e-mail long before 1993, but this is the oldest reference I've found so far.

GE Electronic Mail

To: W.LANGDON

Sub: Saturday, 30 January 1993This is a test of GEnie on our new machine! Our new tape drive

appears to be a good one. I backed up the hard drive, Porter

repartitioned it into three drives, including a small one just for

Aladdin. (This is so if Aladdin crashes and fouls up our file

allocation tables, it doesn't mess up the rest of our stuff.) We

moved Aladdin and associated files this afternoon. It appears to

work and it's even in color!

Some of you may be wondering what our "new machine" was.

In November of 1992, we ordered a "Gateway 2000 clock-doubled 66 MHz 486 machine" (original cow boxes!), with

- 200 Mb hard drive

- 1.44 Mb 3 1/2 inch drive

- 1.2 Mb 5 1/4 drive

- 120 Mb streaming tape drive for backup

- 8 Mb of memory

- 14-inch color SVGA monitor

- 33 MHz local bus

- and a tower case with one expansion slot reserved for CD-ROM. "CD-ROM technology is supposed to make major improvements shortly, so, while it is very attractive, we’re waiting on that one."At

At the time, I wrote the following.

It completely amazes me how much you can get for relatively little money these days. Total cost, including shipping: $3115. I know, that hardly seems “little,” but you have to remember that we once spent $1500 for an Intecolor graphics terminal, and then later had it repaired for $900! And that was when $2400 was worth a lot more than it is now. And our 14-year-old printer cost us $800. I’d really like a new printer, since with the Epson we can’t take advantage of a lot of what the new machines and software can do, and people are more and more frowning on dot-matrix letters. But I have to respect a piece of computer equipment that’s that old and still working as well as the day we got it!

Inflation calculators vary, but most put the cost of that 1993 machine at about $6650 in today's dollars. And our dot-matrix printer? $3300! This is not even attempting to take into account the difference in computing power between then and now. What really blows me away is that the $2400 we paid for the color terminal and its subsequent repair works out to nearly ten grand!

We were normally very good about sticking to a lean budget, but since computing was both vocation and avocation for each of us, well.... All I can say is that it's a good thing we were otherwise quite self-controlled in our spending. When it came to computing equipment, we had colleagues who were even more free-spending than we were—disproportionate to other areas of life. I guess it was the nature of the new, exciting field.

I'm going to have to remember this when it comes time to buy a new computer or a new phone.

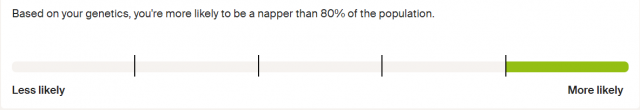

Ancestry was totally wrong about my feelings toward cilantro—they say I'm prone to disliking the herb, but I love it—but they nailed this one.

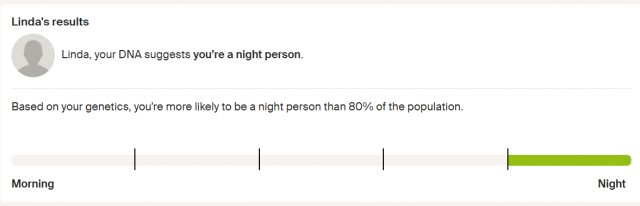

On the other hand, they are 180% out of phase in calling me a night person. Ideally, I'd sleep from 9:30 to 5:00.

So? About as reliable as a horoscope or a gypsy fortune teller?

Maybe, though overall I've found them more reliable than not; it's the areas of disagreement that stand out.

It's a statistical thing, with all the insights and dead-ends statistical analysis can give you. There's a huge database of DNA out there, albeit currently biased towards those of European ancestry (because the sample is self-selected). If we have given permission (another form of self-selection), companies like Ancestry and 23andMe make their anonymized data available for scientific research. They are careful to make the point that what they provide is not itself scientific research, but gives scientists data from which to form hypotheses and choose a direction and an approach for their research. For example, the data indicate that people with blood type A are more likely to have problems with COVID-19 than people with blood type O. (I may have the details wrong here, but you'll get the idea.) In itself, that proves nothing, but has inspired research into why it might be, in hopes of learning more about the disease and its treatment.

Statistically, most people in Ancestry's database with a bunch of the same genetic markers I have are night people, like to take naps, and hate cilantro. All statistical analysis reveals outliers. For my love of cilantro and the morning hours, I am one; for naps, I am not. Ancestry and 23andMe are careful to point out that our DNA is not a fixed destiny; how our genes are expressed can be affected by how we live.

More fascinating yet, Sharon Moalem's book Inheritance: How Our Genes Change Our Lives—and Our Lives Change Our Genes (thanks, Sarah!) reveals that how we live can even impact how we express our genetic inheritance to our children.

Permalink | Read 727 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I've been sorting through old physical and computer files lately. I can't afford to read much of what I process, but occasionally something grabs my attention, and sometimes I find it worth sharing, as a glimpse into the past.

It always surprises me when they say so, but most people these days think of the 1980's as the distant past; it's shocking to me how few people now remember the Berlin Wall, for example. But here's a question I asked in 1989, and I think it's as relevant as ever. I addressed it to teachers, but it goes far beyond education.

I am becoming more and more convinced of the importance of self-confidence in the learning process. There's nothing mysterious about this, of course; I suppose it is quite obvious that it's easier to do anything if you think you can than if you think you can't. At any rate, this is why I was concerned a while back when one of our daughters went through a stage of being convinced—without cause—that she was stupid.

I remember having similar troubles in elementary school myself, but I thought that our children would be immune, because of the openness of their school about standardized test grades (I never knew mine) and the fact that they get letter grades on their report cards instead of the fuzzy comments that I remember.

I was wrong.

Our other daughter, with similar abilities and achievements, had no such difficulty in school, so I did some probing to discover the secret of her self-assurance. I'm sure that her good grades, high test scores, and the praise of her teachers must have some importance, but she dismissed them out of hand, saying, "I know I'm smart because I had third grade spelling words in first grade." Period.

I nearly fell over. In the school where she attended first grade, the children were grouped by ability, regardless of age or grade. Her reading ability put her in with second and third graders for reading and spelling. For reading, this was appropriate; for spelling it was not. Ten to thirty spelling words each week, seemingly random words (no phonetic consistency) that were harder than most of the words she had to learn in fourth grade at her current school. How we suffered (so I thought) over them! In my opinion that was clearly the worst part of her first grade year, one that I would definitely change if I could do it over again. But now she tells me that that was the basis for her positive view of her abilities.

Which leads me to wonder if we are not selling children short. Could it be that they realize that a high score is virtually meaningless if the test was no challenge? That they get more satisfaction out of struggling with something hard than from an unearned, easy success?

What do you say, teachers?

If I got any answer to that question in 1989, I don't remember it. What almost 35 more years of experience have taught me, however, is that (1) Yes, we consistently sell children short, and (2) It's not just a matter of giving children challenges, but of giving them appropriate challenges, because too easy and too hard can each be discouraging.

The question that remains—besides the unanswerable one of how such an individualized program could be achieved in a school setting—is, "How hard is too hard?" My memory of our daughter's experience with a spelling challenge two or three years above her skill level was utter misery that lasted till nearly the end of the school year, when the teacher agreed to back off a bit for her. And yet, and yet, in her mind—and I'm inclined to believe her—it ended up doing her a world of good.

Nobody ever said being a parent was easy!

The Babylon Bee can be educational as well as funny. I'd never heard of "TLDR" until seeing this video, and even so had to look it up: "Too Long, Didn't Read." I'm sure there are many who mentally scrawl those letters on my blog posts, which makes me a little bit sad—but not repentant. If I'm not being paid by the word, neither am I being paid to be concise. But here's a short one for you.

The Bee's TLDR version of the Bible (4.5 minutes) is both amusing and not all that inaccurate. Except that I think better of the Minor Prophets.

Permalink | Read 873 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I've been working my way through old computer files, and found this one-paragraph story starter that I had submitted for the Orlando Sentinel's "Chapter 2000" writing contest of December 1999. The instructions were to write "the first paragraph of a proposed story about the millennium in 100 words or less."

My story won no honors, being sufficiently forgettable that even I have no memory of writing it. But the advantage of having my own blog is that I have a second chance. Oh, look! I won!

The birds awakened him. Marcus drew aside the mosquito netting and sat up, causing his canoe to send gentle ripples across the lagoon. Looking eastward, he smiled. It was a fitting dawn for the new millenium, and well worth missing last night’s party with his co-workers from the Kennedy Space Center. Egrets and herons were better companions at the daybreak of a new age, he thought. As they rejoiced in the splendor of the sky, neither Marcus nor the birds realized that true sunrise was still several hours away, and they were viewing not a beginning, but the end.

I don't think it's a bad beginning, but this is why I don't write fiction: you have to write more than first paragraphs!

Permalink | Read 883 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

There I was, pondering what I might say in today's blog post, when my sister-in-law sent me the following article, from People magazine: "Connecticut 'Witches' Could Be Exonerated 375 Years After Going on Trial." Connecticut Representative Jane Garibay apparently has nothing more important or interesting to do than tilt at windmills.

Local historians and descendants of the Connecticut witches and their accusers hope lawmakers will finally deliver them all a posthumous exoneration. "They're talking about how this has followed their families from generation to generation and that they would love for someone just to say, 'Hey, this was wrong,'" Rep. Jane Garibay told AP. "And to me, that's an easy thing to do if it gives people peace."

Really? The world truly has gone nuts. I'm happy about our family's connection with these women (and the rare man). They hardly need exoneration, especially not from someone who couldn't tell a witch from a warlock.

Instead of accomplishing the work I had intended to do this afternoon, I did a little digging. Here are the people I've found so far among our ancestors who were accused of witchcraft:

My side:

- Mary Perkins, wife of Thomas Bradbury, accused and convicted in Salisbury, Massachusetts but escaped hanging, for reasons unknown. She is my 9th great-grandmother through my father's Bradbury line.

- Winifred King, wife of Joseph Benham, accused three times in New Haven, Connecticut. The first two times, the charge was dropped; the third time she fled to New York. She is my 8th great-grandmother through my father's Langdon line.

My husband's side:

- Mary ----, wife of Thomas Barnes, convicted in Hartford, Connecticut and hanged. She is his 8th great-grandmother through his mother's Scovil line.

Both sides, though not a direct ancestor:

- Mary Bliss, wife of Joseph Parsons, charged but acquitted. She is my 9th great-grandaunt through my mother's Smith line, and also my husband's 9th great-grandaunt through his mother's Davis line.

You'll note that I have not found anyone accused of witchcraft in my husband's father's line, though it is brimming with early New England ancestors. But that's okay, because it is through him that my husband is related to his 9th great-grandfather, Edward Wightman, the last person to be burned at the stake in England for heresy. Edward is also my own 10th great-grandfather, through my father's Langdon line.

Unlike New England's witches, Edward, it seems, was guilty as charged, and more than a little bizarre by the end. But to be a genealogist is to realize that we come from heroes and villains, the oppressed and the oppressor, the innocent and the guilty—and to embrace them all as our own.

To be real you need to celebrate your own history, humble and tormented as it might be, and the history of your own parents and grandparents, howsoever that history be marked by scars and mistakes. It is the only history you will ever have; reject it and you reject yourself.

— John Taylor Gatto

One year ago, the Canadian truckers of the Freedom Convoy rolled into Ottawa, Ontario, their swelling ranks cheered on by people all along their cross-country journey. Protesting Canada's draconian COVID-19 restrictions, they were joined in the capital city by supporters from just about any demographic you can think of. Thanks to everyday folks with cell phone cameras, and indefatigable citizen reporters like David Freiheit* (Viva Frei), we observed the event moment-by-moment, live, unscripted, and unedited. The dissonance between the peaceful, joyful, unifying protest that we saw, and the horrific event portrayed on Canada's national media—picked up, of course, by our own major news sources—was staggering.

(As one who grew up with the seemingly-constant threat of Quebec to secede from the country, one of my strongest memories is of the Québécois at the protest, who declared, "We were Separatists, but after this we are no longer!")

As I watched the days unfold, from the hopeful beginnings to Prime Minister Trudeau's extraordinary invocation of the Emergencies Act, I was moved as I haven't been since 1968, which saw the rise and fall of hope and freedom during Czechoslovakia's Prague Spring. It may not have been Russian tanks rolling through Ottawa as they did through Prague, but the intent was much the same. It took Czechoslovakia another twenty years to win their freedom from Russia; is it better or worse for Canada that their oppression comes from within, instead of from an external enemy?

I've grouped my own posts on the subject here under the topic "Freedom Convoy." If you follow that link you'll see them listed in reverse order (scroll down for the oldest). There you can also see for yourself a selection of Viva's on-the-street videos.

Russia's invasion of the Ukraine obscured both the protest and the issues that provoked it, taking the heat off Prime Minister Trudeau. But I will not let the heroic Freedom Convoy be forgotten—at least in my very tiny corner of the Internet. This beautiful 14-minute tribute by JB TwoFour (about whom I know nothing but this) still moves me to tears.

Permalink | Read 995 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Freedom Convoy: [first] [previous] [newest]

High Flight

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

of sun-split clouds, — and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of — wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov’ring there,

I’ve chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air....

Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue

I’ve topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace.

Where never lark or even eagle flew —

And, while with silent lifting mind I’ve trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand, and touched the face of God.

—John Gillespie Magee, Jr.

Permalink | Read 779 times | Comments (0)

Category Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I liked the AmazonSmile program, in which Amazon.com would donate a percentage of a customer's purchase to the charity of that customer's choice. In general, I'm suspicious of corporate philanthropy, but at least in the case of AmazonSmile, the customer was assured that his money was going to an organization of which he approved.

No more.

Earlier this month I received an e-mail from Amazon, which announced the demise of the program, as of February 20, for the following reason:

In 2013, we launched AmazonSmile to make it easier for customers to support their favorite charities. However, after almost a decade, the program has not grown to create the impact that we had originally hoped. With so many eligible organizations—more than 1 million globally—our ability to have an impact was often spread too thin.

What does this say? What do they mean by "spread too thin"? On its face, it is nonsense: As Amazon itself states, on my AmazonSmile Impact page, "Every little bit counts. When millions of supporters shop at AmazonSmile, charitable donations quickly add up." Charities are not in the habit of rejecting donations of any size, much less those which are bundled into larger amounts for more efficiency, which I'm sure Amazon did. My own chosen charity, the International Justice Mission, received over $204,000 as of November of last year, and I'm sure they were grateful for it. How rich do you have to be to think of that kind of money as insignificant?

Thus I can only interpret this paragraph as, "Amazon is not getting enough recognition, credit, and power over the programs to justify the expense." Especially the power, I suspect.

But Amazon is not giving up on corporate philanthropy. Instead,

We will continue to pursue and invest in other areas where we’ve seen we can make meaningful change—from building affordable housing to providing access to computer science education for students in underserved communities to using our logistics infrastructure and technology to assist broad communities impacted by natural disasters.

In other words, "instead of directing a portion of the money you spend toward the charity of your choice, we will be sending it to the charities of our choice."

As I've said before, if a corporation wants to use company profits to support causes they believe in, or even to buy the CEO a new yacht, that's their business. But Amazon is fooling itself if it thinks this change shows its virtue. Rather, I would think, the opposite.

On a positive note, "using our logistics infrastructure and technology to assist broad communities impacted by natural disasters" seems to me exactly the kind of help Amazon is well-positioned to give, more than many corporations. Companies should think about how they can use their unique strengths and resources in a socially responsible way, rather than simply doling out dollars. That's much more likely to be helpful in the long run.

The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation by Rod Dreher (Sentinel, 2017)

The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation by Rod Dreher (Sentinel, 2017)

I read Live Not By Lies first. The Benedict Option was written three years earlier, and the two make good companion pieces for asking vitally important questions about our lives, our priorities, and our actions. In Live Not by Lies I preferred the first half of the book to the second; with The Benedict Option my reaction was the opposite. I find myself quarrelling with Dreher in a number of places, but nonetheless highly recommend both books, because he is observant, and he is asking the important questions. Dreher predicts very hard times coming for Christians—and others—as our society diverges more and more radically from its classical Western and Christian roots and values.

In my review of Live Not by Lies I mentioned that despite being specifically written for Christians, it's an important book for a much wider audience. The Benedict Option is less comprehensive in scope, especially the first part, but still useful. In Kindle form, it's currently $10, but if you use eReaderIQ and are patient, you can get it for quite a bit less. And don't forget your public library!

You know I'm not in the business of summarizing books. I don't do it well, for one thing. When one of our grandsons was very young, if you asked him what a book was about, he would instead rattle off the whole thing, word for word from memory. I'm like that, minus the superb memory. But secondarily, I don't think summaries do a good book any favors. The author has put together his arguments, or his plot and characters, in the way he thinks best, and trying to pull it apart and reduce it seems to me rude and unfair. Or maybe I'm just trying to justify my weakness, I don't know.

But if I were forced to write my simplest take-away from The Benedict Option, it would be this: Riding along with the current of mainstream culture may have worked all right for us when American culture was solidly rooted in Judeo-Christian and Western ideals, but that time is long gone. Doing the right thing—whatever that might be in a given situation—might never have been easy, but it's harder than when I was young, and it's on track to get much worse.

With that cheerful thought, here are a few quotes. Bold emphasis is my own.

Rather than wasting energy and resources fighting unwinnable political battles, we should instead work on building communities, institutions, and networks of resistance that can outwit, outlast, and eventually overcome the occupation. (p. 12).

I agree wholeheartedly about building communities, institutions, and networks. However, I don't think we should abandon political work. After all, for half a century, Roe v. Wade looked absolutely unassailable, and now there's at least a small crack. Prudence would say to do both: attend to politics (a civic duty, anyway), without putting our faith in political solutions, and at the same time prioritize the building of helpful communities, institutions, networks—and especially families.

The 1960s were the decade in which Psychological Man came fully into his own. In that decade, the freedom of the individual to fulfill his own desires became our cultural lodestar, and the rapid falling away of American morality from its Christian ideal began as a result. Despite a conservative backlash in the 1980s, Psychological Man won decisively and now owns the culture—including most churches—as surely as the Ostrogoths, Visigoths, Vandals, and other conquering peoples owned the remains of the Western Roman Empire. (pp. 41-42).

People today who are nostalgic for the 1960's are mostly those who didn't live through them, I think. It was not a nice time.

Legend has it that in an argument with a cardinal, Napoleon pointed out that he had the power to destroy the church. “Your majesty,” the cardinal replied, “we, the clergy, have done our best to destroy the church for the last eighteen hundred years. We have not succeeded, and neither will you.”

(p. 49).

You can achieve the peace and order you seek only by making a place within your heart and within your daily life for the grace of God to take root. Divine grace is freely given, but God will not force us to receive it. It takes constant effort on our part to get out of God’s way and let His grace heal us and change us. To this end, what we think does not matter as much as what we do—and how faithfully we do it. (p. 52).

[T]he day is coming when the kind of thing that has happened to Christian bakers, florists, and wedding photographers will be much more widespread. And many of us are not prepared to suffer deprivation for our faith. This is why asceticism—taking on physical rigors for the sake of a spiritual goal—is such an important part of the ordinary Christian life. ... [A]scetical practices train body and soul to put God above self. ... To rediscover Christian asceticism is urgent for believers who want to train their hearts, and the hearts of their children, to resist the hedonism and consumerism at the core of contemporary culture. (pp. 63-64).

For most of my life ... I moved from job to job, climbing the career ladder. In only twenty years of my adult life, I changed cities five times and denominations twice. My younger sister Ruthie, by contrast, remained in the small Louisiana town in which we were raised. She married her high school sweetheart, taught in the same school we attended as children, and brought up her kids in the same country church.

When she was stricken with terminal cancer in 2010, I saw the immense value of the stability she had chosen. Ruthie had a wide and deep network of friends and family to care for her and her husband and kids during her nineteen-month ordeal. The love Ruthie’s community showered on her and her family made the struggle bearable, both in her life and after her death. The witness to the power of stability in the life of my sister moved my heart so profoundly that my wife and I decided to leave Philadelphia and move to south Louisiana to be near them all. (pp. 66-67)

Dreher wrote about his sister's struggle and the effect it had on him in The Little Way of Ruthie Leming, which I have also read, and may eventually review. As with all of his books, I have mixed feelings about that one. He idolizes his sister and her choices in a way I find uncomfortable, and reduces almost to a footnote the damage those choices did, to him and to others.

Saint Benedict commands his monks to be open to the outside world—to a point. Hospitality must be dispensed according to prudence, so that visitors are not allowed to do things that disrupt the monastery’s way of life. For example, at table, silence is kept by visitors and monks alike. As Brother Augustine put it, “If we let visitors upset the rhythm of our life too much, then we can’t really welcome anyone.” The monastery receives visitors constantly who have all kinds of problems and are seeking advice, help, or just someone to listen to them, and it’s important that the monks maintain the order needed to allow them to offer this kind of hospitality. (p. 73).

Father Benedict believes Christians should be as open to the world as they can be without compromise. “I think too many Christians have decided that the world is bad and should be avoided as much as possible. Well, it’s hard to convert people if that’s your stance,” he said. “It’s a lot easier to help people to see their own goodness and then bring them in than to point out how bad they are and bring them in.” (p. 73).

Though orthodox Christians have to embrace localism because they can no longer expect to influence Washington politics as they once could, there is one cause that should receive all the attention they have left for national politics: religious liberty. Religious liberty is critically important to the Benedict Option. Without a robust and successful defense of First Amendment protections, Christians will not be able to build the communal institutions that are vital to maintaining our identity and values. What’s more, Christians who don’t act decisively within the embattled zone of freedom we have now are wasting precious time—time that may run out faster than we think. (p. 84).

I know the book was written for Christians, but I wish Dreher had also emphasized how important this is for everyone. No one can afford to ignore the trampling of someone's Constitutional rights, even if they don't affect us personally. If Christians lose their First Amendment protections, no person, no group, no idea is safe.

Lance Kinzer is living at the edge of the political transition Christian conservatives must make. A ten-year Republican veteran of the Kansas legislature, Kinzer left his seat in 2014 and now travels the nation as an advocate for religious liberty legislation in statehouses. “I was a very normal Evangelical Christian Republican, and everything that comes with that—particularly a belief that this is ‘our’ country, in a way that was probably not healthy,” he says. That all fell apart in 2014, when Kansas Republicans, anticipating court-imposed gay marriage, tried to expand religious liberty protections to cover wedding vendors, wedding cake makers, and others. Like many other Republican lawmakers in this deep-red state, Kinzer expected that the legislation would pass the House and Senate easily and make it to conservative Governor Sam Brownback’s desk for signature. It didn’t work out that way at all. The Kansas Chamber of Commerce came out strongly against the bill. State and national media exploded with their customary indignation. Kinzer, who was a pro-life leader in the House, was used to tough press coverage, but the firestorm over religious liberty was like nothing he had ever seen. The bill passed the Kansas House but was killed in the Republican-controlled Senate. The result left Kinzer reeling. “It became very clear to me that the social conservative–Big Business coalition politics was frayed to the breaking point and indicated such a fundamental difference in priorities, in what was important,” he recalls. “It was disorienting. I had conversations with people I felt I had carried a lot of water for and considered friends at a deep political level, who, in very public, very aggressive ways, were trying to undermine some fairly benign religious liberty protections.”

...

Over and over he sees ... legislators who are inclined to support religious liberty taking a terrible pounding from the business lobby. (p. 84-86).

Nothing matters more than guarding the freedom of Christian institutions to nurture future generations in the faith. (p. 87).

Agreed—except that I would put "Christian parents" or just "parents" ahead of "institutions." Dreher is a strong advocate for Christian schools at every level, especially the so-called Classical Christian schools with their emphasis on rigorous academics. However, he gives short shrift to home education, an option that is at least as important and in need of support.

Because Christians need all the friends we can get, form partnerships with leaders across denominations and from non-Christian religions. And extend a hand of friendship to gays and lesbians who disagree with us but will stand up for our First Amendment right to be wrong. (p. 87).

Over and over again I have seen the importance of these partnerships. In all the "fringe" movements I've been a part of, from home education to home birth to small and sustainable agriculture, this collaboration with others with whom we had next to nothing else in common made progress for the movements, and—which was perhaps even more valuable—forced us to work beside and learn to appreciate those who were in other ways our political opponents.

Most American Christians have no sense of how urgent this issue is and how critical it is for individuals and churches to rise from their slumber and defend themselves while there is still time. We do not have the luxury of continuing to fight the last war. (pp. 87-88).

Permalink | Read 1581 times | Comments (0)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Last Battle: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I wrote recently about my pleasant encounter with Shutterfly customer service. That has not changed.

But here's something I'm not too happy about: their new Terms of Service.

I hate reading terms of service, privacy policies, and those scary forms the doctor makes you sign before surgery. I usually pass my eyes over them, but when I sign that I've "read and understood" them, well, let's just say there's more than a little wishful thinking involved. (Especially since parts of the documents are often in a foreign language.) But what can you do? If you don't sign, you don't get your software, or your life-saving operation.

However, ever since PayPal decided that their terms of service should give them the right to steal money from the account of anyone who says something of which they disapprove, I've been more than a little skeptical about what might be hidden in these documents.

Perusing Shutterfly's new Terms, I found the following:

While using any of our Sites and Apps, you agree not to:

- Upload photographs of people who have not given permission for their photographs to be uploaded to a share site.

Think about it. You want to make a photo book or calendar or collage of your vacation photos? What kind of a story will you be able to tell using just photos of unadorned scenery and close family members? I don't know about you, but nearly everywhere I go total strangers get into most of my tourist photos.

No one, you say, is going to go after you because you printed a collage of your trip to Paris. Least of all Shutterfly, which depends on such photos to stay in business. And that's probably true, for the most part. But the language allows for unreasonable interpretations and actions, and my trust that common sense will prevail is far from robust these days. When PayPal can willy-nilly take money out of your own account, when the Canadian government can on a whim freeze its citizens' bank funds, and when people are thrown in jail for nothing more serious than taking pictures from outside the U. S. Capitol building on January 6, 2021, we have to consider not only what people are likely to do based on these documents we sign, but what they are enabled to do.

Permalink | Read 1015 times | Comments (0)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I didn't expect to like this Wall Street Journal article about the board game, Risk. Unlike nearly all the rest of my extended family, I am not a fan of most board games, especially if they involve intricate strategy and take a long time to complete. It's even worse if I'm playing with people who care whether they win or lose. If I ever played Risk, it wasn't more than once.

But I enjoyed the article, and I understood most of it because of having been surrounded by so many people who love to play the game. The author makes a good case that playing the game taught many of us "everything we know about geography and politics."

A certain kind of brainy kid will reach adulthood with a few general rules for foreign policy: Don’t mass your troops in Asia, stay out of New Guinea, never base an empire in Ukraine. It is the wisdom of Metternich condensed to a few phrases and taught by the game Risk.

The game could be played with up to six players, each representing their own would-be empire, and could last hours. The competition could turn ugly, stressing friendships, but we all came away with the same few lessons. ... In the end, no matter who you call an ally, there can only be one winner, meaning that every partnership is one of convenience. If you are not betraying someone, you are being betrayed. Also: No matter what the numbers suggest, you never know what will happen when the dice are rolled. ... Regardless of technological advances, America will always be protected by its oceans. It is a hard place to invade. What they say about avoiding a land war in Asia is true. It is too big and desolate to control. Ukraine is a riddle ... stupid to invade and tough to subdue because it can be attacked from so many directions, making it seem, to the player of Risk, like nothing but border.

Here's my favorite:

The best players ask themselves what they really want, which means seeing beyond the board. I learned this from my father in the course of an epic game that started on a Friday night and was still going when dawn broke on Saturday. His troops surrounded the last of my armies, crowded in Ukraine. I begged for a reprieve.

“What can I give you?” I asked.

He looked at the board, then at me, then said, “Your Snickers bar.”

“My Snickers bar? But that’s not part of the game.”

“Lesson one,” he said, reaching for the dice. “Everything is part of the game.”

And finally, one amazing side note. The man who invented Risk, French filmmaker Albert Lamorisse, also created the award-winning short film, The Red Balloon.

Permalink | Read 1040 times | Comments (0)

Category Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Back in the 1970's, I worked at the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, New York. One of my favorite things to do on my lunch break was to wander over to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit of the associated Strong Memorial Hospital, and watch in admiration as the tiny children fought for their lives. Actually, there were some pretty big infants, too—babies born to diabetic mothers, weighing in at 14 or 15 pounds at birth, but with dangerous complications. My favorites were always the twins, which were commonly born early, and extra small. Not every family had a happy ending, but the best days were when our small "charges" disappeared from view because they had graduated out of the NICU.

I was thinking about this recently because of this story, out of Canada: Doctor Said Mom's Efforts to Save Her Babies Were a "Waste of Time," Now they're 3 and Thriving.

A mom from Canada who went into labor with twins at just shy of 22 weeks gestation was told by her doctor that they would die the day they were born. However, she refused to give up on her babies, and against the odds, her baby girls pulled through, heading home after 115 days in the NICU.

“When I went into labor, the doctor told me, 'The twins will be born today and they will die,'" she said. "I said, 'Excuse me?' and she said, 'Babies this gestation simply do not survive. It’s impossible.' ... She told me she wouldn’t let me see the twins, or hear their heartbeats, because it was a 'waste of time.'"

After four painful days of abysmal care at the unnamed Canadian hospital,

A new doctor entered the room and informed the couple that they could transfer to a London, Ontario, hospital to deliver the twins. ... Luna and Ema were born in London at 9:12 and 9:29 p.m., respectively. Luna weighed just over 14 ounces (approx. 0.39 kg) and measured 11 inches long; Ema weighed 1 pound (0.45 kg) and measured 12 inches long.

The twins were in the NICU for a total of 115 days and were discharged even before their due date. ... Today, the twins are thriving at 3 years old [and] are developmentally caught up to their full-term peers.

Forty years ago, the staff at "our" NICU had told us that they had saved babies born as early as 20 weeks and weighing less than a pound, and expected to continue to improve outcomes and to push the boundaries back. Forty years! I know there has been a lot of progress made in the care of preterm babies since then, primarily from the story of friends-of-friends quintuplets born ten years ago in Dallas.

So how is it that doctors and hospitals are condemning little ones like this to death, and consider 22 weeks' gestation a minimum for survival—and even then only at a few, specialized hospitals. What has hindered the progress Strong Hospital's doctors had so eagerly anticipated?

I can think of a few roadblocks. Number one, perhaps, is that we like to think that progress is inevitable. But there's no little hubris in that. Progress is not guaranteed over time, nor is it consistent.

Then there are funding priorities. Adequate financing may not be a sufficient condition for making progress, but it's a necessary one. Has improvement in preterm baby care been a funding priority over the last 40 years?

And of course there's the most difficult problem of all. Do we, as a society, as a country, as the medical profession in general—do we really want to save these babies? They cost a lot of money: for research, for facilities, for high-tech care, for months in the hospital, and often for special education and care throughout their lives, since babies on the leading edge of the survival curve are at higher risk for lifelong difficulties.

Most of all, does the idea of saving the lives of earlier and earlier preterm babies force us to consider the elephant in the room? How long can a society endure in which we try desperately to save the life of one child of a certain age, while casually snuffing out the life of another child of the same age, based solely on personal choice?

No matter how addictive video games become, I doubt they will ever truly supplant the humble Lego building bricks for enduring value, educational potential, and popularity with both children and their parents. (It's no coincidence that Minecraft, the all-time most popular and best-selling video game, looks a lot like nth-degree Legos.)

So it is with much pleasure that I share this announcement from America's most reliable news source, the Babylon Bee. (It should begin at about the 1:37 mark.)

It's a big win in affordability for the Lego folks, but unfortunately does nothing to address the health hazards of their product. How many more cases of midnight parental foot injury will it take?

Permalink | Read 900 times | Comments (1)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]