Permalink | Read 1037 times | Comments (0)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Since it changed hands, I haven't found the Babylon Bee as interesting as it used to be. Or maybe Facebook has only been showing me their worst efforts recently; sometimes I think Facebook is a conspiracy theory dream all by itself.

In any case, this one is funny on more than one level. Be sure to watch to the end; it's only two minutes long.

Permalink | Read 1046 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Butterflies don't look back at the caterpillar with shame.

Stop looking at your past with shame.

It was a transformation and it brought you here.

I saw this yesterday on a friend's Facebook page. I'm not going to spend any time analyzing it, but use it as the perfect introduction to these cute little guys, who with their companions are devouring our substantial parsley bush.

They're welcome to it. Not because we don't like parsley—we certainly do—but because these babies are pre-transformation swallowtail butterflies.

We get monarchs every year, but haven't had swallowtails since 2018.

Permalink | Read 1231 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I'm guessing not many of my busy blog readers will find it a worthwhile use of 14 minutes to see the latest Viva Frei video, about more Canadian craziness, but I'm sure it could easily happen here. I'm very pleased that we now have two bona fide medical doctors in the family, but I'm beginning to wish we had a lawyer as well.

The short version is that a couple from Alberta was accused of being in contempt of court for violating a court order that they were not a party to, and had not been served notice of. Let that sink in a minute. Spoiler alert: after lawyers representing them pushed back, the Crown retreated, but came after them from a different angle, successfully getting a court injunction against their planned, peaceful protest on private property.

Apparently their protest violated Alberta's strict lockdown regulations, so the Crown had a case for fining the couple for the violation. I believe that suspension of Constituional and/or Charter rights (freedom of assembly, of peaceful protest) in the name of public health has been grossly misused, but that's not the issue. Let it stand for the moment.

What a conviction for contempt of court (either in the case that was withdrawn or through the injunction) does is up the cost of the protest significantly, adding criminal penalties and potential jail time to the fine. One could speculate that the initial imposition of the regulations went through proper legislative procedure (thought I doubt it), but this is an egregious attempt to impose harsher penalties than the law provides for.

Be that as it may, I enjoyed learning about the two types of contempt of court and more about how the system works.

Permalink | Read 1172 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Courage is not simply one of the virtues but the form of every virtue at the testing point.

— C. S. Lewis, in The Screwtape Letters

Permalink | Read 1165 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Last Battle: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Lawyers aren't very popular among the people I know, and even in general are more often maligned and mocked than almost any group of people—except maybe dead white males. I am one of those who frequently rail against lawyers because our increasingly litigious society has robbed us of the ability to make rational risk/benefit assessments, be it in childrearing, schools, medical decisions, playground equipment, government regulations, corporate policy, or almost anything else.

There certainly are bad actors in law, as there are in any field of endeavor. Perhaps the legal profession is at more risk of this than most, given the combination of great power and lots of money to be made. But following the Viva Frei vlawg (law-themed video blog) has made me aware of a very important truth:

The only way to fight bad lawyers is with good lawyers.

It is perilous to mock the professions that stand between us and the disintegration of society, from the policeman on his beat to the Supreme Court justice. That we do so reflects the relative security of our lives—a high form of privilege.

This video (11 minutes), one of several chronicling the defamation lawsuit of Project Veritas against the New York Times, illustrates how lengthy, difficult, and often tedious the process has become. A few bad apples aside, maybe lawyers are earning their hefty fees after all.

Yesterday's video (16 minutes) has an update to the case—the next tedious step—which you can see by clicking on that link. I chose to embed the earlier one as more illustrative, and especially because of the quotation at the end, from George MacDonald, one of my favorite authors. I tend to fast forward over the repetitious stuff after the main story, instead of merely closing the video, because I almost always like David Freiheit's choice of quotations at the very end. In this video, MacDonald is slightly misquoted, but the meaning is unchanged. The correct version, from The Marquis of Lossie, is below.

To be trusted is a greater compliment than to be loved.

Permalink | Read 1249 times | Comments (1)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

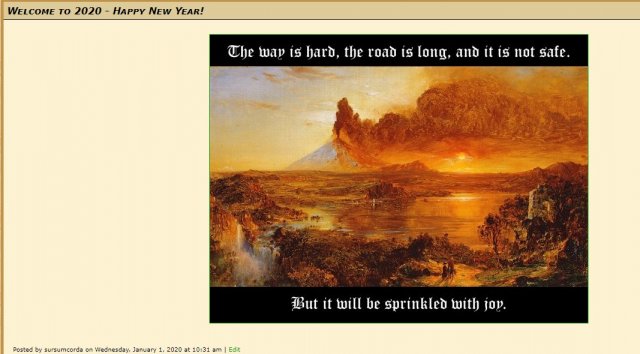

I've never claimed to be a prophet (those guys are supposed to get it all right), but every once in a while I surprise myself. Looking back through old posts, I found this, which I had posted on January 1, 2020:

Permalink | Read 1238 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Being a Floridian, and one who has enjoyed several cruises, I was naturally intrigued by the following Viva Frei episode in which attorneys David Freiheit and Robert Barnes discuss Florida's lawsuit against the CDC's shutdown of the cruise industry. The video is just under 14 minutes long.

As I said, the story was of mild interest to me from the beginning. It was already on my "blog about this, maybe" list. However, it turns out to have a personal angle that makes it even more compelling. Unfortunately, I can't talk about it for privacy reasons, but it serves as a clear though pleasant reminder that no matter how nameless and faceless the machinations of government and business seem, there are real, everyday people behind them all. We forget that to our peril.

Last Sunday, Viva & Barnes revisited the story, reporting that the judge, instead of ruling on the case, sent both parties to mediation. (The relevant part of the video is 26:18 - 28:29.)

Here is another example of what a difference "spin" makes in news reporting. Barnes clearly sees the mediation order as an indication that the judge would rule in favor of Florida if he had to, and as a way for the him to let the CDC save face while keeping himself from being accused of "killing granny." However, most news articles I read have reported it as a setback for Governor DeSantis, and pointedly place the blame for cruise ships fleeing Florida, not on the CDC's restrictions, but on both DeSantis and the Florida Legislature for forbidding discrimination against people who have not been vaccinated.

I certainly hope that Barnes is right, and more accurate in his analysis of the judge's inclinations than he was of the judge's gender—though these days I'll admit the latter is a trickier call than it ought to be.

Part 1 is here. Now for more of our adventures during our December attempt at choosing joy and life amidst a pandemic-inspired focus on fear and death.

The eight of us did most of our venturing-outside-the-home together (being blessed with a car that seats that exact number), but occasionally we split up, as when two of us spent a day at EPCOT and the rest of us sought our entertainment at a classic American mini-golf course. Both groups had great fun. Credit goes to Disney for keeping their parks open and at the same time uncrowded so that the experience felt safe as well as fun. Remember that back then we knew much less about outdoor transmission (or lack thereof) of the virus, and people were nearly as scared outdoors as inside. The golf course was similarly comfortable.

Left: Congo River Golf; Right: EPCOT at night. Click to enlarge.

We also separated to give Janet and Stephan a chance to celebrate their anniversary on their own. They chose a hotel on Daytona Beach, and we joined them the next day for the chance to swim in the Atlantic Ocean on the first day of winter. Porter and I declined the swim, as it was 66 degrees, cloudy, and windy. That didn't stop the hardy Swiss, however! I didn't realize until we arrived that they had chosen a hotel on the same section of beach where I spent so many happy hours as a child—a five-minute walk from my grandparents' house. The coquina-built bandshell is much the same, and so is the ocean, but almost nothing else.

Closer to home, we visited the Orange County History Center, which thoughtfully made it possible to see the good stuff while avoiding the decidedly-child-inappropriate special exhibit of history's darker side. We picked out and decorated our Christmas tree, made cookies, and generally prepared for the holiday, which is not surprisingly much more fun with children around. We visited playgrounds, worked on various projects at home, swam some more, and sang and played music together.

Only twice in our entire month together did I feel the least bit uncomfortable with regard to COVID-19. The worst was at our local pizza party arcade, since we arrived at a time when a large party of people without masks crowded the place. Fortunately it was easy to return later.

The second time was at Sea World. I mean no particular criticism of the park, which clearly took precautions very seriously: taking temperatures, requiring masks, keeping even the outdoor stadiums at low, well-distanced capacity. But overall the park was more crowded than allowed for comfortable distancing, unlike our experience at EPCOT. However, this was on December 23, one of the busiest days of the year, one we'd normally have avoided like the plague. (Perhaps that analogy isn't the best one to use at this time.) The experience was overall delightful and certainly much more pleasant than it would have been in a normal year.

More to come.

Permalink | Read 1539 times | Comments (1)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

What are you saying NO to today, so you can say YES to something better?

(S. D. Smith, author of the Green Ember series.)

Permalink | Read 1099 times | Comments (0)

Category Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

According to this article,

During an interview on CNN's "State of the Union," [CDC director Rochelle] Walensky was asked about vaccinated Americans who have contracted the virus—and whether anyone has died from an infection, despite being inoculated. Walensky said the CDC is aware of 223 so-called "break-through" infections in vaccinated Americans, but clarified that many of those individuals died due to other causes. "Not all of those 223 cases who had COVID actually died of COVID," she said. "They may have had mild disease but died, for example, of a heart attack."

This makes perfect sense to me. From the beginning of this pandemic, I have been frustrated by seeing a clear tendency to report all deaths in anyway associated with COVID-19 as caused by the virus. Witness the testimony of a friend of ours, a nurse, who (in another state) was ordered to count as new, active COVID-19 cases anyone who tested positive for the COVID-19 antibodies—which meant that many cases were counted multiple times. And that of an Emergency Medical Technician I know who only partially joked, "If someone with COVID-19 is run over by a truck, his death is counted as a COVID-19 death." Then there's the death I know about that was put down as due to COVID-19 but should have been "nursing home neglect." Of course these are isolated examples, but good luck trying to convince me that they aren't representative of widespread mis-information.

What it comes down to is this: What are you trying to prove?

When the powers-that-be were trying to justify elaborate and invasive regulations in reaction to the pandemic, it was to their advantage that the numbers be as large as possible. But when the object is to reassure the public of the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, the advantage lies in giving the virus no more blame than is absolutely undeniable.

I happen to believe that the CDC is closer to the truth in the case of the vaccine, but that's not the point. What's important is that with every report, every news story, every rumor,

Always, always, always ask, Cui bono?

Who benefits? What are they trying to prove? Follow the money.

This is the post I started to write five months ago, but postponed to make sure everyone involved got through their quarantines and other impedimenta successfully.

I like to think that we've been more careful than most during this pandemic, though more due to the concern of our children (who apparently think we are "old") than our own. But when you're retired, and introverted, and not easily bored, staying home is a pretty easy option. We wore masks before our county made them mandatory, shopped only for what we deemed necessities, and used the stores' "senior hours" when we could. I'm also the only person I know who consistently washed (or quarantined) whatever we brought home.

But all that isolation, particularly the lack of physical touch, is hard even on introverts.

Hardest of all was cancelling our big family reunion scheduled for April 2020—coinciding with what was supposed to be the first visit home in six years of our Swiss family. Following close behind were missing our nephew's wedding, our normal summertime visit to the Northeast, and our long tradition of a huge family-and-friends Thanksgiving week of feasting and fun, all of which would have involved being with most of our American-based family. Plus the breaking my fourteen-year streak of travelling overseas to visit our expat daughter and her family (one year to Japan, thirteen to Switzerland).`

I know that doesn't begin to compare with the hardship endured by those who were forceably separated from loved ones who were sick or dying. But when the "temporary measures to keep our hospitals from being overwhelmed" turned into unending months of restrictions—with our hospitals so far from overcrowded as to be financially strapped due to underutilization—even normally compliant people like us began to chafe.

Even as we relaxed and let go of much of our fear, we remained vigilant in our precautions, for a very good reason: a light, not at the end of the tunnel, but a much-needed illumination in the middle of the tunnel. We needed to stay healthy, because...

The reunion remained off the table, due to onerous quarantine requirements imposed by the states the rest of our family live in. But thanks to much work on their part, and a state government more enlightened than most, our European family was able to visit us in December. Rarely have I been so happy to be living in Florida, which welcomed them with open arms. So of course did we! Mind you, I think the CDC was still recommending we wear masks all the time with visitors and stay six feet apart, but naturally that didn't last six seconds! A year apart from family is far too long, and that goes tenfold for grandchildren. Sometimes you just do what you have to do.

We did the risk/benefit analysis—and made the joyful choice.

Porter had to drive to Miami to pick them up, because so many flights had been cancelled. But he would have driven farther than that to bring them home!

We had been prepared to stay mostly around the house, just enjoying each other's presence. And at first we did a lot of that, since merely being in America was adventure enough for the grandkids. But they were here for a month, and most of the tourist attractions had reopened, albeit at reduced capacity, so we took full advantage.

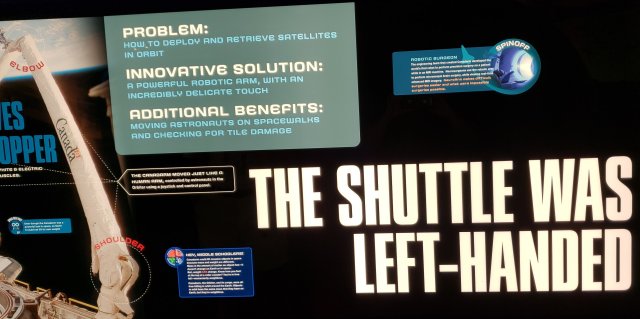

Kennedy Space Center was amazing. We were not the only visitors in the park, but at times it seemed like it. Sadly, some of the attractions were still COVID-closed, but there was certainly plenty to see. The following photo is for the lefties in our family:

One of the trips I enjoyed the most was to Blue Spring State Park, which was visited by more manatees than we've ever seen naturally in one place. The weather was perfect—that is, cold. Cold weather drives the manatees from the ocean and the rivers into the relatively warm water (about 72 degrees) of the springs. The air temperature made most of us keep our masks on even though that was not required except inside the buildings, since we discovered them to be very effective nose-warmers.

Another favorite activity was swimming. (Not with the manatees; that's no longer allowed.) The intent was for most of it to be in our own pool, and indeed it was, but there had been a glitch: We purchased a pool heater, knowing that our pool temperatures in December can dip into the 50's (Fahrenheit). However, the unit that was supposed to have been installed before our guests arrived was delayed again and again. Whether it was actually the fault of the pandemic is anyone's guess, but that's what took the blame. It finally arrived just a few days before they had to return to Switzerland. Until then, the children swam bravely, if not at length, in the cold water, and all of us enjoyed the (somewhat) heated pool at our local recreation center. And then they really appreciated our own heated pool for those last few days.

To be continued....

Permalink | Read 1480 times | Comments (1)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

This may explain a few marital frustrations. (Credit to someone on Facebook but I can't find it again to share it.)

Permalink | Read 1382 times | Comments (3)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The Wild Robot and The Wild Robot Escapes by Peter Brown (Little, Brown 2016, 2018)

The Wild Robot and The Wild Robot Escapes by Peter Brown (Little, Brown 2016, 2018)

When everyone in the house (adult, 17, 14, 12, 10, 8, and 6) approves of a book, I generally find it worth looking into, despite my well-ingrained—and more often than not justified—prejudice against recently-written children's books. Peter Brown's Wild Robot books were definitely worth the reading.

Brown's story of a robot cast away on an uninhabited (by humans) island and how its programming directs its adjustment there, and in later adventures, is very well done, reminding me of Isaac Aimov's treatment of the practical and ethical issues of a society that includes multitudes of robotic machines.

There's love and conflict and tragedy and emotional struggles, all handled sensitively. I can't say I like these books better than S. D. Smith's Green Ember series, which my readers know I love greatly, but they are less dark—and less violent, despite some scary adventures. I detected no warning bells for my very sensitive grandchildren on the other side of the family. They may especially enjoy that the main character is female (if one can say that about a robot) who is strong and smart, gentle and motherly.

Sure, I could make some complaints, but they're minor and overshadowed by the good.

So ... Canada is now saying, "It's not as bad here as in North Korea, or Nazi Germany." And we can say, "It's not as bad here as in Canada." Not exactly progress, is it?

As a mathematician I can say it is, actually—with a minus sign.

That was from May 7. Today we have this.

This is not sensationalism and fearmongering. Viva Frei is careful to see many sides of an issue. So am I, and I fully acknowledge that not everyone sees the same line separating civil disobedience from selfish thuggery.

Following the rules is necessary for a functional civilization.

Blindly following the rules is necessary for a functional tyranny.

Respecting one another is necessary for a functional humanity.

I'm going to leave it at that for now.