Next up in this series of interesting YouTube channel subscriptions: Everything Music, by Rick Beato. I was going to say that I can't remember what introduced me to to Rick Beato's channel, but a look back at one of my own posts gave me the answer: Google apparently decided I would be interested in it, popping up a suggested video on my phone. For once they were right.

My gateway to Beato's channel was the musical abilities of his young son, Dylan. There are several Dylan videos, but this one is a good 13-minute compilation:

It turns out that the Dylan videos are but a small part of Everything Music. Beato covers so much; I'll let him give the intro (13 minutes).

Music theory, film music, modal scales, tales from his own interesting musical history, and a whole lot of modern music about which I know little and like less.

Remember what I said about Excellence and Enthusiasm?

I'm a child of the 60's, chronologically, but unlike most of my generation, I've never liked rock music, nor any of its relatives and derivatives. Granted, growing up when I did there was no getting away from it, and there were a few specific songs I did enjoy. At one point, I was even a minor fan of Jefferson Airplane, and attended one of their wild, live concerts. That point in my life, while embarrassing, reminds me of this line from C. S. Lewis' Screwtape Letters: "I have known a human defended from strong temptations to social ambition by a still stronger taste for tripe and onions." Who knows what trouble I might have gotten into in my college years had I not had a stronger taste for what is loosely called classical music?

What, specifically, don't I like about the rock genre(s)?

- The music is almost invariably played at ear-splitting volume, literally ear-damaging.

- Most of the music comes with lyrics, and with a few exceptions, I find that they range from boring to abominable.

- The heavy emphasis on pounding rhythms drives me crazy; I never have liked playing with a metronome.

- The timbre of the electric guitar, nearly ubiquitous in rock music, is one of a very few that I generally find unpleasant (saxophone is another).

Enter Rick Beato. If his son's abilities are astounding, Rick's aren't all that far behind, and his experience, knowledge, and enthusiasm keep me interested in his analysis even though most of his examples are from music I can't stand. It helps a lot that he uses short excerpts, in which neither lyrics nor pounding beats have a chance to do much harm. Plus, I control the volume.

I especially enjoy Rick's videos on modal music, as that has always interested my ear. It does seem really odd to hear him talk about modes without any reference to church music, in which modal music was once really big. But I had no idea how important modes are in rock music and film scoring, and learning through Rick's videos has been a delight. Hiding underneath all that raucous sound and those objectionable lyrics is a lot of complex and very interesting music. It's not going to make me a rock music fan, but it gives me more appreciation for the skill of the musicians behind it—if not for their sometimes questionable moral compasses. (I know, classical composers were not necessarily saints, either. There's a reason I generally prefer instrumental music.) It has also heightened my awareness of the music that undergirds our movies and television shows, and why it is often so powerful.

Here's an interesting Gustav Holtz/John Williams comparison from one of his movie music videos (16 minutes):

That's enough for an introduction; I'm sure I'll be posting more Everything Music videos in the future.

Permalink | Read 2183 times | Comments (0)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Music: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] YouTube Channel Discoveries: [first] [next] [newest]

I've mentioned before situations in which fear has led to unreasonable responses to the COVID-19 threat. Whether by governments or by private citizens, that's a bad thing. However, this is still funny.

For those who are wondering, HEMA stands for Historical European Martial Arts.

Permalink | Read 1110 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I'm starting a new series of posts featuring YouTube channels I've found interesting and which I think others might enjoy, too. Some were recommended by friends; some I just happened upon in the almost-random way one does online.

Today? Chateau Love.

The writers (producers? hosts?) are friends of ours, so I would have subscribed in any case. But this is also an example of what I wrote about yesterday, of how excellence and enthusiasm draw me into an appreciation of subjects that I might otherwise give a miss.

Our friends Vivienne and Simon have recently started their own vlog (video blog), featuring life at and around their château in France. Without meaning in any way to diminish Simon's many contributions, I'll focus on Vivienne in this introduction because she's clearly the hostess and narrator of the vlog, and because we've known her longer and better.

Vivienne is an artist. I mean a "real" artist, whose paintings have been exhibited in Paris. Now that sounds really impressive, and it is, but you do have to bear in mind that for a number of years Paris was her home. She's an American, married to a Brit—but they've called France home for a long time. When I say she is an artist, however, I mean much more than her paintings. Vivienne puts beauty and elegance into everything she touches, whether it's a small, temporary apartment, a huge French château, a simple meal, a feast for the neighborhood, or a birthday Easter basket for an enchanted guest. Our tastes differ in many respects: not only am I incapable of the amazing feats of home decor Vivienne achieves, but also I wouldn't want that for our house. It's not my style. That does not stop me from standing in awe of the beauty that looks as if it could be in a museum. What she does with food, now—that's welcome in our house any day.

Watching the Chateau Love videos, you might assume that Vivienne and Simon must be wealthy. I assure you they are ordinary human beings with ordinary human struggles and no trust funds! Vivienne is incredibly talented at finding bargains as well as making something both useful and beautiful out of items the rest of us would casually toss in the trash. (See the "Louis XVI coathooks" in Episode 2.)

Vlogging is a new project for them, a bit of pandemic-and-lockdown-stress relief. I'm also excited to watch the growth of Chateau Love as they gain experience and new equipment. May this be a very long-running show!

Below are the first three episodes. So far they have each been just under 30 minutes long, and published on a once-a-week schedule. As a bonus, you can hear music by Vivienne's talented singer sister, Ashley Locheed. And you can occasionally catch glimpses of Janet & Stephan's flower girl—much grown up.

Episode 1: Romance, DIY, A Dodgy Haircut & Who We Are!

Episode 2: Dramatic Bedroom-Bathroom Reveal, DIY Chateau Bed, Cheesy Meltdown, & Winter Wonderland!!

For some reason the second video is not playing here on my blog, though the first and third are. You can see it on YouTube itself by clicking on the title link. I'll leave the embedded video up while I try to find out what's going on.

Episode 3: Wine Tasting, Vineyards, Plants, Cheese & Pony Pedicures!

Do you see a man skilful in his work? he will stand before kings - Proverbs 22:29 (RSV)

Excellence is almost always a joy to behold. A well-crafted piece of furniture, a musical performance of great artistry, a fabulous meal, a well-run business, an amazing athletic feat—I think we are hard-wired to find great skill attractive. Something done well is not necessarily something worth doing, and it is all too easy to value the wrong things simply because they are excellently done. But the excellence itself is good.

I'm sure we could all be better at whatever we do, if we would only put enough time and focused effort into it. If we don't find that possible, or desirable, however, there's another attractive factor that can fill in some of the gaps: Enthusiasm. Often something merely "good enough," if approached with passion, can be delightful. Not always: Florence Foster Jenkins comes to mind, but even she had famous admirers and once sold out Carnegie Hall.

Passion for a subject often encourages hard work, long hours, and perseverance, which in turn can take native talent to greatness. When excellence and enthusiasm meet, the result is attractive indeed.

This is why I sometimes find myself really enjoying YouTube videos covering subjects in which I have previously had little to no interest. You'll see some of them in an upcoming series of posts featuring channels to which I've recently subscribed. The usual caveats apply: I like to make available to others books, articles, and videos I have found to be of some value, even if I don't agree with everything presented. Your mileage may vary. Take what is helpful to you; leave the rest.

I may not agree with, or even understand, all that I see and hear, but I love the skill and passion with which it is presented.

Permalink | Read 1379 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Last week the air conditioning came on; today we are back to heating. That's Florida Spring for you. One day you sleep with the ceiling fans awhirl; the next you are very glad you haven't gotten around to putting away the extra blankets.

Snce I love the cooler weather, I'm not sorry for its return. Of course, that's "cooler" as in mid-40's lows, and mid-70's highs, which qualifies as a warm spring day where I spent my childhood. :)

Anything lower than that might discourage the blossoming citrus trees, whose heavenly odor is one of my favorite signs of Florida Spring.

Permalink | Read 1109 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Mistborn: The Final Empire by Brandon Sanderson (Tor 2006)

Mistborn: The Final Empire by Brandon Sanderson (Tor 2006)

At last I ventured into Mistborn territory, at the urging of my brother and my grandson, and because I've read and enjoyed a couple of other Sanderson books. I was reluctant to get involved with a series of very long books (this one is 541 pages), but there's a difference between a 500-page nonfiction book—even a really enjoyable one—and good fiction of similar length. This book did not take long to read, and the only reason I haven't moved on to The Well of Ascension, the second book in the series, is that our library doesn't have it. I've submitted a request....

I can't say I love Brandon Sanderson's writing as much as our grandson does, at least not yet. It's impossible to judge a book like this on first reading, especially when it's part of a series, but I didn't feel the deep connection to the good, the true, and the beautiful I've felt in my favorite books, such as J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, C. S. Lewis's Narnia stories, and S. D. Smith's Green Ember books. Even in my favorite authors that connection is not the same in all their works: it's there, for example, in Lewis's Space Trilogy, but not nearly as strongly. That's okay; authors aren't required to be completely consistent, and they are allowed to grow and develop. :)

What I can say for certain about this first Mistborn book is this: it's clever, it's wildly complex, and it's enjoyable to read. It's more explicitly dark in places than I would prefer, and quite violent, but the foundation of the story still feels good, not evil. And there's no doubt that Sanderson is a clever, skilled, and thoughtful writer.

We'll see what the next book brings.

I've just discovered another reason I'm keeping my masks when all this brouhaha is over.

Two nights ago I woke up in the middle of the night with post-nasal drip and a persistent cough. I was too tired to recognize the symptoms at the time, but the morning's "snowfall" made the cause clear: it's oak pollen season again. The last thing I had done before going to bed had been to take some mild exercise on the back porch, in the cool of the night. It usually helps me sleep—but not when it sends oak pollen deep into my lungs.

Last night I had an inspiration, and did my bedtime exercises while wearing my mask. Porter can't wear a mask while exercising because it immediately gets drenched with sweat. But did I mention that these are mild exercises? Not a problem. A little weird, but okay. And of great benefit: I slept very well. (I would have said, "like a baby," but in my experience babies wake up every two hours or so at night and want to eat. Who made up that simile, anyway?)

Two data points aren't enough for correlation, let alone causation. But they are enough for hope.

What current generations think of as ancient history is as alive as yesterday to those of us who lived through it.

A long time ago (1970's) in a galaxy far, far, away (the state of New York), a new mother innocently asked if it was normal to experience orgasm while breastfeeding. (It's not common, but it happens. Just as orgasm during childbirth sometimes happens. Not to anyone I know, though.)

These were days when natural childbirth was just beginning to gain popularity, and breastfeeding was still considered to be a bit weird, especially by doctors. The woman was reported to the authorities (some version of Child Protective Services) who decided she must be a sexual deviant. They forceably separated her from her baby. My memory of it is a bit hazy, but I believe it was after La Leche League got involved that the situation was resolved in the mother's favor—but by then she and her nursing infant had been separated for several days. The justification given by the authorities for their behavior, not to say their ignorance, was that it is better to falsely traumatize 100 innocent families than to let one potential evildoer slip through their hands. Sadly, this family was far from the only one similarly torn apart in those days. Maybe it's still going on; I don't know. I'm not as close to those issues as I was back then.

These memories came back in strength as I listened to this Viva Frei report. Freiheit isn't any happier than I am that COVID-19 is pre-empting so much of his law vlog, but needs must when the devil drives. Who indeed but the devil can be driving Canada to force apart law-abiding, healthy Canadian families—including very young children?

The Regional Municipality of Peel is near Toronto, Ontario. There the recommendations for what to do if someone in your child's class or daycare tests positive for COVID-19 include the following:

The child must self isolate, which means:

- Stay in a separate bedroom

- Eat in a separate room apart from others

- Use a separate bathroom, if possible

- If the child must leave their room, they should wear a mask and stay 2 metres apart from others

Remember that this includes elementary school children, and even those in day care. Very young children are to be isolated from their families—from their mothers!—for two weeks. Two weeks is a very long time in child-years.

And this is for children with no symptoms at all. What about those who are sick, whether or not with COVID-19? Is a child with an upset stomach to be left in his own vomit? What are these people thinking?

What child, even a healthy one, can endure 14 days of isolation without mental and emotional scars? In prisons, solitary confinement is a serious punishment. Freiheit makes the legitimate point that people who have been arrested on suspicion of having committed a crime have more protections than those who are suspected of possibly harboring the COVID-19 virus.

Another question comes to mind: Do all Canadians have big houses and small families? Or does the government plan to take away the children of people who don't happen to have a bedroom to spare for isolation? Apparently the fear that such official interference will take their children is driving some parents to comply with these horrendous rules. That and the $5,000 fine for non-compliance. If parents did these acts on their own they would be accused of child abuse.

I apologize if some of you think I'm being too alarmist, and maybe listening to too many YouTube videos. And yet I don't apologize—someone has to broadcast what's happening. Someone has to tell the victims' stories. Freiheit himself thought at first this had to be false news, but couldn't avoid the conclusion that it is all too real.

There is a little good news: apparently there has been enough outrage over these regulations that some politicians are now distancing themselves from them. It's an ongoing story. But one thing is for sure: If people don't speak up, the road from bad to worse is a swift one.

I like the Viva Frei video law blog, in part because although David Freiheit pulls no punches he is also generally happy, positive, and willing to see more than one side of a situation. But this pandemic—or more precisely, governmental reaction to the pandemic—is taking its toll on his optimism.

I haven't said much here about the horrendous rules now in place for anyone who dares try to enter Canada—Canadian citizens included—but I'm posting the following because, as Freiheit says, people need to know.

I've set the video to start part way through. The first story, about employees at a Canadian Tire store going vigilante on a man who was not wearing a mask, is definitely concerning. Here in Florida we had someone in a convenience store check-out line actually pull a gun on a woman who was standing too close for his comfort. But in the Canadian Tire event there is stupidity on both sides, and I think its inclusion distracts and detracts from the main story, in which the Canadian government is the problem.

In short, in the name of safety, the Canadian government has taken the authority to compel people, including Canadian citizens, to be taken off to undisclosed locations and detained for an indeterminate time without due process. Heinous enough, but more harrowing is that these people are not told where they are going, and their families are not told where they are going. What's more, once they arrive at their "quarantine hotels," they are not allowed to use social media, and not allowed to disclose their locations.

So there you go. Innocent people with every right to be in Canada, whisked off to detention facilities, and no one knows where they have gone, other than that government officials have taken them. They can't leave, and they can't tell the world what's happening to them. Presumably all this is done in the name of public health, in fear of COVID-19. (I can't, however, imagine how the communications blackout is contributing to anyone's well-being.) This means that in addition to being "disappeared" and alone, these people are likely sick and alone. Even in the best of times we all know how closely their families must watch out for people in hospitals and nursing homes, because if they don't, bad things happen. They just do. I've lost track of the number of such incidents I know about personally. What are the odds these people are getting good medical care? As you can tell from the news story, they're not even getting decent security.

I'm aware that some people reading this will find Freiheit a bit too excitable. As I said, he's always enthusiastic about what he says, but as the situation in Canada gets more and more oppressive, he's getting more and more upset.

Perhaps rightly so.

I'm a bona fide mask agnostic. I've always considered wearing a mask a small thing to do to make other people feel more comfortable, and have worn one in most public situations since before they were required.

But I hate 'em (even though ours are creations of beauty), hate still more that they are mandatory in so many places, and can't wait until "this too shall pass." (Though I plan to keep my masks and continue to use them in occasional, appropriate situations, such as on an airplane, when I'm not feeling up to par and am out in public—and also when my nose is cold.)

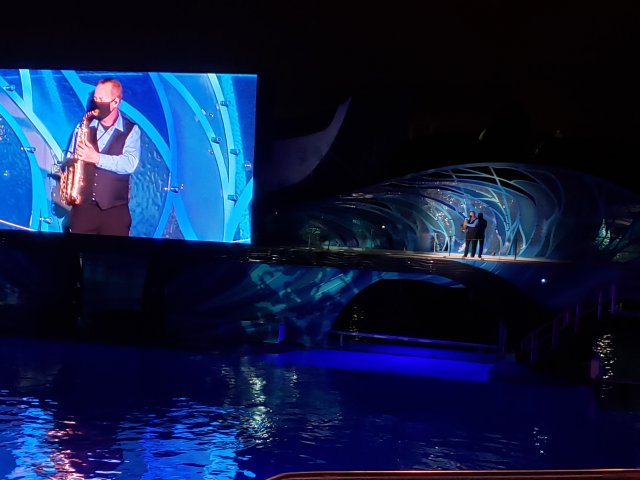

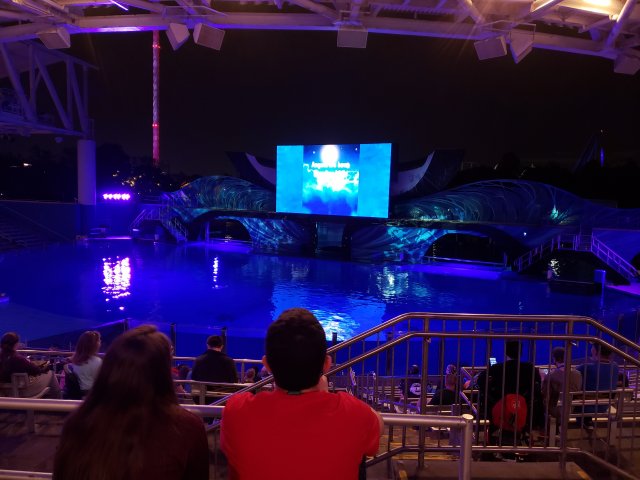

Masks are not magic, and the more people treat them that way, the more skeptical I become. The following photos are from a visit to Orlando's Sea World. Note that the saxophone player—though alone on stage—is wearing a mask. Now check out, in the next picture, how far away he is from the audience.

This is a prime example of the religion of masks, of masks as magic. Some have insisted to me that the sax player must wear a mask to set a good example for the visitors to the park, though everyone I saw was already wearing masks, for the simple reason that they didn't want to get thrown out of the park they'd paid so much to get into. To me, such extreme maskism only says to me that no one here is thinking about what makes a mask effective. Nothing from that man's mouth or nose—let alone his instrument—was going to reach far across the water to infect someone, even if he were to scream at them at top volume.

People are, in general, willing to follow rules that make sense to them. Take away the sense, and even the most compliant folks start to question everything. It's like the "lawyer warnings" that come with every new appliance these days. With rules such as "don't use this hair dryer while taking a shower" receiving as much prominence as warnings that a sane person might actually need to hear, most people don't bother to read them at all.

As I said, I'm a mask agnostic. I guess my philosophy is reduce the viral load, whether it's COVID-19 or a common cold virus. I'm pretty sure masks do this. As far as I've been able to tell, there's no hard scientific evidence that proves the effectiveness of mandatory mask-wearing, but basic logic says that it's better not to get sneezed on. Wearing a mask in situations when it might reduce the transmission of this strange new virus is a logical extension I can get behind. (Making it mandatory is another issue, but one I'm not going to deal with here.)

Which brings me to the inspiration for this post, which came from a Mauldin Economics newsletter. It's only anecdotal evidence, not scientific, but it's an encouraging word that masks can make a difference. The story is from a recent conference, mostly video but with some in-person participants.

They had a small group of live participants ... [who did not wear masks but] were tested before anyone came and were tested every day during the conference. By the end, a significant portion of the attendees had acquired COVID-19.... Interestingly, they had 17 production staff, who all wore masks and intermingled with the unmasked participants. They were tested, too, and not one came down with the virus.

There are many questions that come to mind, not least of which is where the COVID-19 came from if all the participants tested negative before arrival. But the fact that none of the masked production staff caught the virus encourages me that mask-wearing does, indeed, reduce the viral transmission.

This seems like a good time to add the comment I've been itching to make, misquoting by just one letter a distant relative, Henry of Navarre (King Henry IV of France) when he chose to become a Catholic. I can't believe I'm the first to say it, but Google seems to think so.

Our planned trips to Europe keep getting cancelled on us, so I don't know when I'll have the chance to worry about face-covering rules in France. But whenever we return, there's no doubt in my mind:

Paris is worth a mask.

Permalink | Read 1360 times | Comments (2)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

O. J. Simpson, Casey Anthony, George Zimmerman, Donald Trump ... pick your favorite villain. There's someone out there who you are certain "got away with murder." It rankles, doesn't it? Makes you doubt our system of justice. Me? I'm just as guilty, though I worry more about the uncounted criminals who "get off on a technicality" when everyone involved knows they're guilty—including their own attorneys.

In the court of public opinion, we are all vigilantes. And that's a problem.

We have a lawyer friend who has seen our criminal justice system from several angles, having served for years as a prosecuting attorney, and for years as a defense attorney. I well remember a somewhat heated discussion with him, which started when I mentioned that I like the British system, in which a defense attorney, if he becomes convinced his client is guilty, must step down. (As I understand it, that was at least the case in the past. For all I know it might have changed.) Our friend is a gentle, mild-mannered man, but he vehemently disagreed, insisting that even the most guilty person is entitled to the best possible defense his attorney can provide. Maybe that's why the British attorneys stand down, figuring they can't do their best if they believe their client guilty. Apparently American defense lawyers have no such inhibitions. At least not the good ones.

All that to say, when a lawyer takes on what we believe to be the "wrong" side of a case, that doesn't make him a villain. And when a jury returns a verdict we disagree with, that doesn't make them wrong. They're all doing their jobs, and vitally important jobs they are.

In litigation, sometimes even when you win, you still lose. — David Freiheit.

In the American justice system, one does not need to be proven innocent to be acquitted. Because "innocent until proven guilty" is a bedrock principle, the burden of proof is on the prosecutor, who must show the accused to be guilty "beyond reasonable doubt." Small wonder that We the People, inflamed by media coverage, believe we know better than those who have seen the evidence and heard the arguments. We want to see our version of justice done without any respect for or patience with the due process guaranteed every one of us. Yes, the system sometimes fails, sometimes makes mistakes; I've seen it fail among our own family and friends. But vigilante "justice" is a terrifying prospect. It's time to reprise A Man for All Seasons again.

Current society is taking vigilantism to new heights. It's long been true that many of those found not guilty in law courts have nonetheless had their lives ruined (or even ended) by the opposite verdict from the court of public opinion. Now, however, the "String him up!" reaction extends not simply to the former defendant, but even to his attorney, as you can see in the following video.

If you are thinking of becoming a lawyer, and you are so sensitive to the thoughts of others that you sometimes require protection from them, you probably want to find a new line of work. — David Freiheit.

I never had aspirations of becoming a lawyer; I don't think I have the right personality. But even I can see that what this unnamed law school did to attorney David Schoen—rescinding a teaching offer in fear that Schoen's previous job as an attorney for President Trump would make some students and faculty feel uncomfortable—is doing a tremendous disservice to the students they hope to prepare for legal practice. Not to mention to society as a whole. Don't take my word for it; Freiheit says it better.

People don't seem to fully appreciate how dangerous a practice this actually is. — David Freiheit.

Humble Pi: When Math Goes Wrong in the Real World by Matt Parker (Riverhead Books (2020)

Humble Pi: When Math Goes Wrong in the Real World by Matt Parker (Riverhead Books (2020)

My sister-in-law and I don't often read the same books, but she has an uncanny ability to discern books I might like. Her recommendation of Humble Pi was a winner.

Matt Parker is a funny writer, and has in spades the usual mathematician's love of puzzles and wordplay. The pages of his book are numbered from back to front—with a twist. Between Chapter 9 and Chapter 10 is Chapter 9.49. The title of his chapter on random numbers is "Tltloay Rodanm." His index is ... interesting.

Not all of the book's quirks are good ones. Parker insists on using "dice" as both singular and plural, which is quite annoying to the reader (or at least this reader); he explains: My motto is "Never say die." Funny, but still irritating. Less funny and more frustrating is his insistence on using "they" as a singular pronoun, even when there is no ambiguity of sex involved. Still less amusing are the jabs he takes at President Trump: they are irrelevant, unkind, and will date the book before its time.

Okay, I've gotten past what I didn't like about the book. Now I can say I recommend it very highly. Despite all the math, it's easy to read. Parker does a good job of explaining most things. Even if you skip the details of the math—and computer code—you can appreciate the stories. It's possible, however, that you'll become afraid to leave your house—and not too sure about staying there. The potential for catastrophic math and programming errors is both amusing and terrifying. Much worse than failing your high school algebra test. On the other hand, you'll gain a greater appreciation for how often things actually go right in the world, despite all our mistakes.

Even if you're one of those who skips the quotation section, be sure to scroll to the bottom before leaving, because Matt Parker also has a YouTube channel, called Stand-up Maths.

I document the quotations with the book's page numbers as written, so higher numbers indicate earlier text.

What is notable about the following quote is that it is the first time I recall seeing affirmed in a "mainstream" publication (and by a mathematician, no less) the claim I first encountered in Glenn Doman's book, How to Teach Your Baby Math.

We are born with a fantastic range of number and spatial skills; even infants can estimate the number of dots on a page and perform basic arithmetic on them. (p. 307, emphasis mine)

With all that advantage right from the get-go, you'd think we could do better than this:

A UK National Lottery scratch card had to be pulled from the market the same week it was launched. ... The card was called Cool Cash and came with a temperature printed on it. If a player's scratching revealed a temperature lower than the target value, they won. But a lot of players seemed to have an issue with negative numbers:

"On one of my cards it said I had to find temperatures lower than -8. The numbers I uncovered were -6 and -7 so I thought I had won, and so did the woman in the shop. But when she scanned the card, the machine said I hadn't. ... They fobbed me off with some story that -6 is higher, not lower, than -8, but I'm not having it." (pp. 307-306)

I'm sure the lottery players are not, in reality, as stupid as this would imply. Don't they all dress more warmly when their thermometers read -20 degrees than when they read -1 degree? But so many people have a major disconnect between real life and the math they learned (or didn't learn) in school.

Did you know this? I didn't. We long ago gave up the Julian calendar for the more accurate Gregorian version,

But astronomy does give Julius Caesar the last laugh. The unit of a light-year, that is, the distance traveled by light in a year (in a vacuum) is specified using the Julian year of 365.25 days. (p. 291)

At 3:14 a.m. on Tuesday, January 19, 2038, many of our modern microprocessors and computers are going to stop working. And all because of how they store the current date and time.... (p. 291)

It's easy to write this off as a second coming of the Y2K "millennium bug" that wasn't. That was a case of higher level software storing the year as a two-digit number, which would run out after 99. With a massive effort, almost everything was updated. But a disaster averted does not mean it was never a threat in the first place. It's risky to be complacent because Y2K was handled so well. Y2K38 will require updating far more fundamental computer code and, in some cases, the computers themselves. (p. 288, emphasis mine)

You don't think math is an important subject? Sometimes when you get the math wrong, no one notices. Sometimes the only victim of your mistake is yourself. But sometimes, lots of people die.

The human brain is an amazing calculation device, but it has evolved to make judgment calls and to estimate outcomes. We are approximation machines. Math, however, can get straight to the correct answer. It can tease out the exact point where things flip from being right to being wrong, from being correct to being incorrect, from being safe to being disastrous.

You can get a sense of what I mean by looking at nineteenth and early-twentieth-century structures. They are built from massive stone blocks and gigantic steel beams riddled with rivets. Everything is over-engineered, to the point where a human can look at it and feel instinctively sure that it's safe. ... With modern mathematics, however, we can now skate much closer to the edge of safety. (p. 265)

A rose by any other name ... might get deleted.

In the mid-1990s, a new employee of Sun Microsystems in California kept disappearing from their database. Every time his details were entered, the system seemed to eat him whole; he would disappear without a trace. No one in HR could work out why poor Steve Null was database Kryptonite.

The staff in HR were entering the surname as "Null," but they were blissfully unaware that, in a database, NULL represents a lack of data, so Steve became a non-entry. (p. 259)

Only those who know nothing about computers really trust them. The rest of us know how easy it is for mistakes to happen. I use spreadsheets a lot, and the chapter on how dependent many of our critical systems are on Microsoft Excel leaves me weak in the knees.

Excel is great at doing a lot of calculations at once and crunching some medium-sized data. But when it is used to perform large, complex calculations across a wide range of data, it is simply too opaque in how the calculations are made. Tracking back and error-checking calculations becomes a long, tedious task in a spreadsheet. (p. 240)

The flapping butterfly wing of a tiny mistake can lead to disaster of Category Six hurricane proportions.

In 2012 JPMorgan Chase lost a bunch of money; it's difficult to get a hard figure, but the agreement seems to be that it was around $6 billion. As is often the case in modern finance, there are a lot of complicated aspects to how the trading was done and structured (none of which I claim to understand). But the chain of mistakes featured some serious spreadsheet abuse, including the calculation of how big the risk was and how losses were being tracked. ...

The traders regularly gave their portfolio positions "marks" to indicate how well or badly they were doing. As they would be biased to underplay anything that was going wrong, the Valuation Control Group ... was there to keep an eye on the marks and compare them to the rest of the market. Except they did this with spreadsheets featuring some serious mathematical and methodological errors. (p. 240-239)

For example (quoted from a JPMorgan Chase & Co. Management Task Force report),

"This individual immediately made certain adjustments to formulas in the spreadsheets he used. These changes, which were not subject to an appropriate vetting process, inadvertently introduced two calculation errors.... Specifically, after subtracting the old rate from the new rate, the spreadsheet divided by their sum instead of their average, as the modeler had intended. This error likely had the effect of muting volatility by a factor of two and of lowering the [Value-at-Risk calculation]." (p. 238)

As a result,

Billions of dollars were lost in part because someone added two numbers together instead of averaging them. A spreadsheet has all the outward appearances of making it look as if serious and rigorous calculations have taken place. But they're only as trustworthy as the formulas below the surface.

Don't get me started on the reliability of the computer models we use to make momentous, life-and-death decisions.

The following quote is from the chapter on counting, which features a serious argument over how many days there are in a week. But I include this just because the author raises a question for which the answer seems so obvious I wonder what I'm missing.

Some countries count building floors from zero (sometimes represented by a G, for archaic reasons lost to history) and some countries start at one. (pp. 205-204)

Lost to history? Isn't it obvious that the G stands for "Ground"?

It will be clear to any regular blog reader why I've included the next excerpt, and why it is so extensive.

Trains in Switzerland are not allowed to have 256 axles. This may be a great obscure fact, but it is not an example of European regulations gone mad. To keep track of where all the trains are on the Swiss rail network, there are detectors positioned around the rails. They are simple detectors, which are activated when a wheel goes over a rail, and they count how many wheels there are to provide some basic information about the train that has just passed. Unfortunately, they keep track of the number of wheels using an 8-digit binary number, and when that number reaches 11111111 it rolls over to 00000000. Any trains that bring the count back to exactly zero move around undetected, as phantom trains.

I looked up a recent copy of the Swiss train-regulations document, and the rule about 256 axles is in there between regulations about the loads on trains and the ways in which the conductors are able to communicate with drivers.

I guess they had so many inquiries from people wanting to know exactly why they could not add that 256th axle to their train that a justification was put in the manual. This is, apparently, easier than fixing the code. There have been plenty of times when a hardware issue has been covered by a software fix, but only in Switzerland have I seen a bug fixed with a bureaucracy patch. (p. 188)

Our modern financial systems are now run on computers, which allow humans to make financial mistakes more efficiently and quickly than ever before. As computers have developed, they have given birth to modern high-speed trading, so a single customer within a financial exchange can put through over a hundred thousand trades per second. No human can be making decisions at that speed, of course; these are the result of high-frequency trading algorithms making automatic purchases and sales according to requirements that traders have fed into them.

Traditionally, financial markets have been a means of blending together the insight and knowledge of thousands of different people all trading simultaneously; the prices are the cumulative result of the hive mind. If any one financial product starts to deviate from its true value, then traders will seek to exploit that slight difference, and this results in a force to drive prices back to their "correct" value. But when the market becomes swarms of high-speed trading algorithms, things start to change. ... Automatic algorithms are written to exploit the smallest of price differences and to respond within milliseconds. But if there are mistakes in those algorithms, things can go wrong on a massive scale. (pp. 145-144)

And they do. When the New York Stock Exchange made a change to its rules, with only a month between regulatory approval and implementation, the trading firm Knight Capital imploded.

Knight Capital rushed to update its existing high-frequency trading algorithms to operate in this slightly different financial environment. But during the update Knight Capital somehow broke its code. As soon as it went live, the Knight Capital software started buying stocks of 154 different companies ... for more than it could sell them for. It was shut down within an hour, but once the dust had settled, Knight Capital had made a one-day loss of $461.1 million, roughly as much as the profit they had made over the previous two years.

Details of exactly what went wrong have never been made public. One theory is that the main trading program accidentally activated some old testing code, which was never intended to make any live trades—and this matches the rumor that went around at the time that the whole mistake was because of "one line of code." ... Knight Capital had to offload the stocks it had accidentally bought ... at discount prices and was then bailed out ... in exchange for 73 percent ownership of the firm. Three-quarters of the company gone because of one line of code. (pp. 144-142)

I've had the following argument before, because schools are now apparently teaching "always round up" instead of the "odd number, round up; even number, round down" rule I learned in elementary school. Rounding up every time has never made sense to me.

When rounding to the nearest whole number, everything below 0.5 rounds down and everything above 0.5 goes up. But 0.5 is exactly between the two possible whole numbers, so neither is an obvious winner in the rounding stakes.

Most of the time, the default is to round 0.5 up. ... But always rounding 0.5 up can inflate the sum of a series of numbers. One solution is always to round to the nearest even number, with the theory that now each 0.5 has a random chance of being rounded up or rounded down. This averages out the upward bias but does now bias the data toward even numbers, which could, hypothetically, cause other problems. (p. 126)

I'll take an even-number bias over an inaccurate sum in any circumstances I can think of at the moment. Hypothetical inaccuracy over near-certain inaccuracy.

It is our nature to want to blame a human when things go wrong. But individual human errors are unavoidable. Simply telling people not to make any mistakes is a naive way to try to avoid accidents and disasters. James Reason is an emeritus professor of psychology at the University of Manchester, whose research is on human error. He put forward the Swiss cheese model of disasters, which looks at the whole system, instead of focusing on individual people.

The Swiss cheese model looks at how "defenses, barriers, and safeguards may be penetrated by an accident trajectory." This accident trajectory imagines accidents as similar to a barrage of stones being thrown at a system: only the ones that make it all the way through result in a disaster. Within the system are multiple layers, each with its own defenses and safeguards to slow mistakes. But each layer has holes. They are like slices of Swiss cheese.

I love this view of accident management, because it acknowledges that people will inevitably make mistakes a certain percentage of the time. The pragmatic approach is to acknowledge this and build a system robust enough to filter mistakes out before they become disasters. When a disaster occurs, it is a system-wide failure, and it may not be fair to find a single human to take the blame.

As an armchair expert, it seems to me that the disciplines of engineering and aviation are pretty good at this. When researching this book, I read a lot of accident reports, and they were generally good at looking at the whole system. It is my uninformed impression that in some industries, such as medicine and finance, which do tend to blame the individual, ignoring the whole system can lead to a culture of not admitting mistakes when they happen. Which, ironically, makes the system less able to deal with them. (pp. 103-102)

My only disappointment with this analogy is that I kept expecting a comment about how "Swiss cheese" is not a Swiss thing. If you get a chance to see the quantity and diversity of cheese available at even a small Swiss grocery store, you will understand why our Swiss grandchildren were eager to discover what Americans think to be "Swiss cheese."

If humans are going to continue to engineer things beyond what we can perceive, then we need to also use the same intelligence to build systems that allow them to be used and maintained by actual humans. Or, to put it another way, if the bolts are too similar to tell apart, write the product number on them. (p. 99)

If that had been done, the airplane windshield would not have exploded mid-flight, even though several other "Swiss cheese holes" had lined up disastrously.

How do you define "sea level"? Well, it depends on what country you're in.

When a bridge was being built between Laufenburg (Germany) and Laufenburg (Switzerland), each side was constructed separately out over the river until they could be joined up in the middle. This required both sides agreeing exactly how high the bridge was going to be, which they defined relative to sea level. The problem was that each country had a different idea of sea level. ...

The UK uses the average height of the water in the English Channel as measured from the town of Newlyn in Cornwall once an hour between 1915 and 1921. Germany uses the height of water in the North Sea, which forms the German coastline. Switzerland is landlocked but, ultimately, it derives its sea level from the Mediterranean.

The problem arose because the German and Swiss definitions of "sea level" differed by 27 centimeters and, without compensating for the difference, the bridge would not match in the middle. But that was not the math mistake. The engineers realized there would be a sea-level discrepancy, calculated the exact difference of 27 centimeters and then ... subtracted it from the wrong side. When the two halves of the 225-meter bridge met in the middle, the German side was 54 centimeters higher than the Swiss side. (pp. 89-88)

Now, here's the video I promised.

Matt Parker's videos share the strengths and weaknesses of his book. You'll notice in the video below his insistence on using plural pronouns for singular people, even when he knows perfectly well that he is talking about a man or a woman. Except for when he apparently relaxes and lapses into referring to the man as "he" and the woman as "she." What a concept. What a relief.

I include this particular video because he tackles a question I've long wondered about. I'm accustomed to making the statement that Switzerland is half the size of South Carolina, usually noting that it would be a lot bigger if they flattened out the Alps. But how much bigger?

I posted previously some of the reasoning behind our decision to get a COVID-19 vaccine. Here's how it played out.

Initially I was not impressed by the system for administering the vaccines. Porter spent a week or so on the computer (and once on the phone) trying to get an appointment, only to run into all sorts of website problems and be locked out until all available appointments were gone. Again and again. He had signed up with at least three venues for notification of available vaccine. Finally, Orange County came through.

The website was definitely a problem, and from what I heard the websites of the other vaccine providers were no better. (And still aren't.) After navigating some glitches and laboriously entering pages of personal data, we finally came to a page where we could choose a (supposedly) available date and time. At that point the system would fail. Most times, fortunately, it would send us back to the "pick a time" screen to try again. But sometimes it would crash more seriously, and send us further back. More than once Porter had to re-enter all the personal data. I didn't get ejected that far; most of the time it was just a matter of click-fail, click-fail, click-fail ... for 40 minutes. Then suddenly, Porter's machine came back with "appointment confirmed"! Five minutes or so later, so did mine. It felt like winning the lottery! (Not that either of us has ever experienced winning the lottery. But we can imagine.)

Porter and I have each been paid to make computer systems work, so I will allow myself I little frustration at the poor IT work done these days. I blame decades of relentless cost-cutting, lowest-bid contracts, and consequent poor morale—though I admit prejudice in the matter, having lived through it ourselves. In any case, the website design left much to be desired—a situation which, incidentally, we have found at several other governmental websites, including those of the U. S. Mint and the Affordable Care Act.

We know much less about the medical and logistical side of administering the vaccines themselves, but from a personal point of view, we were much impressed.

For the first dose of the vaccine, we drove down to the Orange County Convention Center, where the bottom floor of a parking garage was set up for very efficient work. We never had to leave our car. It helps that the OCCC was designed to handle crowds, and the wait was not too long as we wended our way toward the entrance. We had filled out most of the paperwork online, and had just a few brief medical questions and maybe a signature or two to deal with at this point. The biggest surprise was discovering that we were getting the Pfizer vaccine, since the online paperwork had specified Moderna. We didn't care which we got as long as the second dose was the same brand.

Bar codes kept track of who we were and what we were getting. The one question that arose was quickly answered by a doctor who was zooming from car to car, as needed, on a skateboard! After a quick jab we were shunted to an outside parking lot for 15 minutes of waiting to be sure we didn't pass out, go into shock, or grow horns. One more scan of our bar codes and we were off home. A smooth-as-silk process, expertly handled. For us, the whole affair took about two hours, the majority of which was travel time.

Four weeks later, we reprised the event. The lines of cars and the vaccination process were faster, but the traffic getting to the Convention Center was worse, so elapsed time remained about the same. Nothing to complain about.

"What about the after effects?" you ask. For the first vaccine, nothing at all but a slight soreness at the vaccination site, just as with any shot. For the second, it appeared to be the same until almost exactly 72 hours later, when Porter developed mild flu-like symptoms: muscle aches, tiredness, slight headache, and feeling as if he might be getting a fever (though we didn't confirm that). They lasted about six hours, after which he was fine.

Did I have that reaction, too? We'll never know. You see, that was the day I had chosen to have a troublesome tooth extracted, and when Porter started showing symptoms I was so doped up on fever-reducing and pain-killing medications (one extra-strength Tylenol and three Advil every six hours, as needed) that anything would have been completely masked. Vaccine reactions were far from my thoughts at that time.

Contrary to the way some folks read my previous post, I am most definitely not in favor of mandatory vaccinations. :) Voluntary vaccination is a different matter, however, and we are happy to have this under our belts. Here's a shout-out to all those who made the process go so smoothly. (But can you look into getting the website fixed, please?)

Note to those urging everyone to get vaccinated: If you don't soon ease up on the restrictions placed on those who have chosen to be vaccinated, you'll be giving a huge negative incentive to those who have not.

Is this poking the bear? It's not original; I found it and it made me laugh. We need some laughs!

Permalink | Read 1155 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Yesterday I had a tooth extracted. I was sent home with a bewildering list of do's and don'ts, but the one I remember best is this:

Go home. Eat ice cream. Watch movies.

Compliance has not been an issue.