I'm certain Facebook had no idea what it was doing when it banned my 9/11 memorial post. Suddenly I started looking into others who claimed unfair and unreasonable censorship, people I had previously ignored. Contrary to what I had been led to believe, I have yet to find anything extremist, evil, hateful, or even particularly objectionable—certainly nothing as egregious as other offenses that Facebook seems to have no problem with. What I've seen has been at worst annoying. Of course I find things I disagree with (what else is new?) but also a lot that is interesting, reasonable, and fits with the world as I know it. Nothing, that is, that could justify Facebook's censorship.

I doubt that Facebook's intent in banning certain content was to inspire me to investigate that content, but that's not an unusual reaction. Ban a book or a movie and you generate interest in what would probably have died an ignoble death on its own. Were it not that platforms like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and such are so massive, and virtual monopolies, I would be less concerned.

Here's just one example. Even if the following video were not about censorship, it would be amazing, as I have never before been fascinated by legal language.

David Freiheit is a Canadian lawyer who gave up litigation for full-time video commentary on current issues from a legal standpoint. From what little I've seen of his YouTube channel, his style is a little on the crazy side, but he makes legal issues and legal documents interesting, which qualifies him as a miracle worker as far as I'm concerned.

Two things particularly struck me in watching this. The first is that I had no idea how lucrative Facebook advertising can be—the advertising that I generally ignore. For me, Facebook is a place for communicating with family—or friends, since most of my family has now deserted the platform—and I ignore the larger picture. But there's another world out there, a world of high finance, a world where there are worse consequences for offending the Facebook gods than having your post deleted. Can you even imagine a world where Facebook can demonetize your post, which takes away the percentage of ad revenue that you normally receive, and thus cost you over a million dollars a month?

Secondly, I was unaware of the practice of not just cutting off, but actually stealing that ad revenue. If I have an ad-revenue contract with Facebook, and they delete my post, I merely lose the income. But if they leave the post up, and merely demonetize it, they can still run ads—but Facebook (YouTube, whatever) gets all the revenue, rather than having to share it with the content provider. In other words, by determining that your content is somehow "wrong" they can take for themselves all the ad revenue the post generates.

This is from my understanding of the process, not from the video below. What the video adds is the idea that the "independent fact checkers," in determining that a post is "false," themselves benefit by doing so, since they can include links to their own content and funnel income from the original content poster to themselves, which is a huge conflict of interest and a positive incentive to label something as false. I get that one would want to be able to click to the reasoning behind such a label, but at the very least the fact-checkers should not profit from it. Anyway, if you have 23 minutes and are curious as to how legalese can possibly be interesting, here it is.

Permalink | Read 1240 times | Comments (1)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

(Modified from something found on Facebook.)

Happy 2020 Thanksgiving to all!

Permalink | Read 1078 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

My father was an engineer with the General Electric Company. He worked in several places, including Erie, Pennsylvania and Lynn, Massachusetts, and maybe some others I don't know because that was before I was born. Later in life he worked at Valley Forge and Philadelphia in Pennsylvania. But for most of my childhood he was at company headquarters in Schenectady, New York. He had a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering, and a master's in physics, and I almost never knew what he did in his job. The genealogist in me regrets that I was so incurious, but he couldn't have told me anyway, as much of his work was classified. Once, many years later, when were visiting the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia (where in retirement he worked as a docent), he pointed to a photo in an exhibit on military airplanes and casually said, "That was one of my projects."

Dad didn't spend a lot of time on the road, but he did have "business trips" that took him around the country. Again, I never knew what for—nor, as a child, was I aware of much besides the souvenirs he'd bring back with him. It's hard to believe that he used to fly in prop planes, though I do remember him expressing his regret that the Schenectady Airport consigned itself to being a backwater of the Albany Airport when it chose not to make the runways long enough to accommodate jets.

By 1960, however, he was enjoying jet travel between here and California. And I mean enjoying. General Electric was not the kind of company to send engineers First Class, or even Business Class if they had had it back then. But in those golden days of flying, Coach was a little different. Here's what he wrote in his diary about one particular trip.

September 25, 1960

This morning I caught Eastern Airlines' 8:40 a.m. flight along with Renato Bobone from Albany to New York City and thence by Trans World Airlines' Boeing 707 jet to Los Angeles and a week in that city. The flight, as is often the case in a jet, was rather uneventful. We left New York at 11 a.m. with overcast weather and it was not long after we were on our way that dinner began. It was interesting to note than TWA left a copy of Newsweek and Life on the table between each pair of seats for passengers’ reading. A good idea.

Dinner started off with the usual two drinks. Then a crabmeat cocktail with two glasses of white wine followed by dinner with two glasses of red wine or champagne.

Dinner was roast beef that I had trouble identifying. I think it was roast tenderloin. Anyway it was very good. For dessert I ignored the calorific foods and had a bunch of grapes. And coffee.

Not too long after this repast, we began flying over the mountains and I sat in the lounge to get some pictures. I may have some fair ones. The flight took us over the southern edge of the Grand Canyon, but haze may have prevented my pictures from being their best. The desert was very interesting to watch. It looks desolate, yet must contain much life. I would like to be able to see it first hand and leisurely sometime.

We landed in Los Angeles about 12:20 Pacific Standard Time and we checked into the Hyatt House. We rested a bit and then Renato and I took advantage of the Hyatt House swimming pool and the sunny day. I also spent some time staring at the TV at the San Francisco - New York professional football game. The Giants won 21-19.

(I confess my near-total ignorance of professional sports when I reveal that I laughed when I read that last line, since I assumed a San Francisco vs. New York game meant that somehow the Giants were playing the Giants.)

That really was the golden age of coach-class flying, with jet-speed travel, lots of room, and sumptious meals. Not to mention at least six free drinks. Plus, if his times were correct, I make the flight time from New York to Los Angeles at four and a half hours, at least an hour quicker than is standard today.

And yet it wasn't all sunshine and lollipops. Here's what he wrote about the return flight.

I got on the plane about 10:00 and by after 10:30 the plane had not left. Someone reported they were waiting for someone on a connecting flight, but the hostess said she didn't believe that was the real reason. Eventually the agent came aboard and announced over the public address system, "All passengers please deplane immediately. We have a bomb scare." We all left right away with no excitement or panic. We were locked in the waiting room while they removed the baggage and searched the plane. They served jus coffee and pastry while we waited.

Eventually we were all interviewed by the FBI—the interview consisting of questions as to name, address, reason for trip, were we involved in a court action, had we reeived threats, might someone be playing a practical joke un us? Then we identified our luggage, stood by while it was searched, and thence back to the plane. We took off three hourse late. The flight back was really uneventful, although as usual I got only about 2 hours' sleep.

We came to New York to find rather couldy skies and a moderate delay before we could land. Since I had an 11 a.m. flight out of La Guardia [having landed at Idlewild], I was not anxious to see much in the way of delays. We finally got off the plane at 10:15 but I did not get my bag until 10:30. The cab driver said it was a 20 minute trip to La Guardia and he made it in 20 minutes. I dashed to the Eastern Airlines counter and thence to the gate to find them just about to pull the stairs away from the plane. I got aboard—but I was the last one to make it.

Permalink | Read 1228 times | Comments (4)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Robert Heinlein wrote that the Year of the Jackpot was 1952. It's a pity he died in 1988, because he would have loved 2020.

In one of those serendipitous Internet moments, I recently came across the answer to a puzzle that has been nagging at me for months. Longer, really.

Every time I'd shake my head and say, "The world has gone completely insane"—which I have been doing a lot this century—I'd remember a science fiction story from my distant past. I couldn't recall the title, the author, nor enough of the plot to begin to find it, though I tried halfheartedly now and again.

Then it was handed to me on a platter, in the form of a notification from eReaderIQ that a book from an author I'm following (Robert Heinlein) was on sale for 99 cents. It was called The Year of the Jackpot and is in reality a short story, not a book. You can read it for free right here, at the Internet Archive.

I knew as soon as soon as I saw the title that this was the story I had been remembering. Heinlein is a mixed author: some of his works are brilliant and delightful, others quite frankly off-the-rails unpleasant. This one is not a happy tale, but it is fascinating and enjoyable.

Here's one of my favorite paragraphs:

He listed stock market prices, rainfall, wheat futures, but the "silly season" items were what fascinated him. To be sure, some humans were always doing silly things—but at what point had prime damfoolishness become commonplace? When, for example, had the zombie-like professional models become accepted ideals of American womanhood? What were the gradations between National Cancer Week and National Athlete's Foot Week? On what day had the American people finally taken leave of horse sense?

Pretty mild compared with the decades-long "silly season" we're in now, isn't it? But the ending, well....

Potiphar Breen is a statistician whose hobby is charting cycles. And in the year 1952 they are not looking good at all.

Permalink | Read 1272 times | Comments (2)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I've been having fun cleaning out computer files, and came upon some old photos that may me wonder just how much our personalities are determined at birth or very early in our childhoods.

.jpg)

Here I am at age five, drinking water after enjoying a hike in the Adirondacks, wearing comfortable clothes and not sitting cross-legged. Comfort remains my highest criterion for choosing clothing, I have always loved spending time in the woods, water is my beverage of choice, and I have never, ever been able to sit cross-legged without serious discomfort.

Here's evidence from age six that my mother did her best to nurture my feminine side and teach me to be a proper young lady of the times. It didn't take. You can see by the expression on my face my heroic struggle to endure privation and torture for completely unfathomable reasons. Nothing has changed.

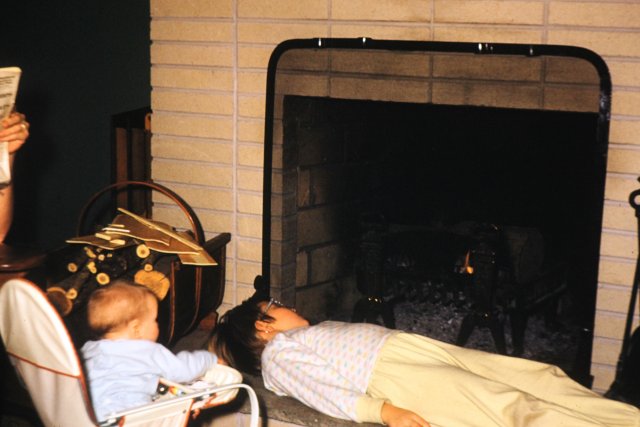

As a young mother, Thanksgiving at my in-laws' place in Moncks Corner, South Carolina, usually found me collapsed on the hearth in front of a comforting fire. This picture from Christmas at my grandparents' house in Rochester, New York shows that when I was seven I felt much the same way.

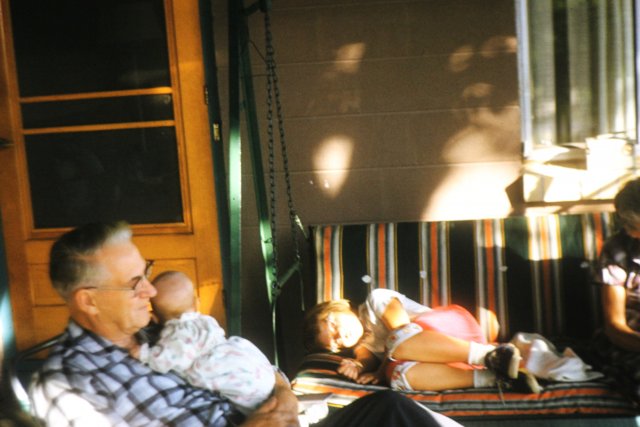

When this swing was new, it graced my grandfather's house. When he moved in with my family in Pennsylvania, the swing came with him. That particular swing is gone now, but when Porter found one for all practical purposes identical at our local Lowes, I had to have one for our Florida back porch. North or south, for more than 60 years I have found it one of the most comfortable places ever to sit, rock, read, think ... and sleep.

I don't mean we can't change. Nature vs. Nurture should no longer be a debate, since the answer is so clearly "both/and." But it still surprises me when I come across evidence—in myself and others—that many of our present characteristics were manifested very early on, if we'd had the eyes to see. Mostly it's fascinating; it only becomes depressing when I look back and realize I'm still fighting battles it seems I ought to have long since conquered and moved on.

So I wonder: Should we, as parents, be more alert to problems in our children that could lead to trouble in the future, and deal with them, rather than letting them slide and hoping they'll outgrow them? If so, which ones are manifestly bad and need eliminating (e.g. lying, laziness, disobedience), and which ones are just part of what makes us individuals (such as a need for solitude, a sensitive nature, or a very logical mind), in which case our job is to help the child both take advantage of the good and develop coping strategies for the bad?

Permalink | Read 1625 times | Comments (2)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Well, would you look at that: the feast day of my 28th great-grandmother (and Porter's 26th) is November 16. Monday.

She's Saint Margaret of Scotland (c. 1045 - 16 November 1093).

In my genealogical work I hadn't gotten much further than to place her in my family tree as the wife of Scotland's King Malcolm III (Canmore). Yesterday, however, I was inspired by a friend's question to dig deeper.

Here is a bit about Saint Margaret, from her Wikipedia article. (All quotations are from the article.)

Margaret, also known as Margaret of Wessex, was the granddaughter of English King Edmund Ironside (c. 990 - 1016). She was born in exile in Hungary, her father, Edward the Exile, having been sent away by King Canute after the Danes conquered England. Later she returned to England and grew up in the English court until she fled to Northumbria after the Norman Conquest.

According to tradition, the widowed Agatha [Margaret's mother] decided to leave Northumbria, England with her children and return to the continent. However, a storm drove their ship north to the Kingdom of Scotland in 1068, where they sought the protection of King Malcolm III.

That's Malcolm, son of King Duncan—see Macbeth, though it takes many liberties with history, not unlike today's movies.

Two years later, Malcolm and Margaret married, and she became Queen of Scots.

Margaret [is credited] with having a civilizing influence on her husband Malcolm by reading him narratives from the Bible. She instigated religious reform, striving to conform the worship and practices of the Church in Scotland to those of Rome. ... She also worked to conform the practices of the Scottish Church to those of the continental Church, which she experienced in her childhood. Due to these achievements, she was considered an exemplar of the "just ruler", and moreover influenced her husband and children, especially her youngest son, the future King David I of Scotland, to be just and holy rulers.

[Quoting the Encyclopedia Britannica] "The chroniclers all agree in depicting Queen Margaret as a strong, pure, noble character, who had very great influence over her husband, and through him over Scottish history, especially in its ecclesiastical aspects. Her religion, which was genuine and intense, was of the newest Roman style; and to her are attributed a number of reforms [of the Church in Scotland]."

She attended to charitable works, serving orphans and the poor every day before she ate and washing the feet of the poor in imitation of Christ. She rose at midnight every night to attend the liturgy. She successfully invited the Benedictine Order to establish a monastery in Dunfermline, Fife in 1072, and established ferries at Queensferry and North Berwick to assist pilgrims journeying from south of the Firth of Forth to St. Andrew's in Fife. She used a cave on the banks of the Tower Burn in Dunfermline as a place of devotion and prayer. St. Margaret's Cave, now covered beneath a municipal car park, is open to the public. Among other deeds, Margaret also instigated the restoration of Iona Abbey in Scotland. She is also known to have interceded for the release of fellow English exiles who had been forced into serfdom by the Norman conquest of England.

Margaret was as pious privately as she was publicly. She spent much of her time in prayer, devotional reading, and ecclesiastical embroidery. This apparently had considerable effect on the more uncouth Malcolm, who was illiterate: he so admired her piety that he had her books decorated in gold and silver. One of these, a pocket gospel book with portraits of the Evangelists, is in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, England.

Margaret was canonized in 1250 by Pope Innocent IV.

In the bizarre tradition of fighting over saints' body parts and other relics, my saintly grandmother did not fare well.

Not yet 50 years old, Margaret died on 16 November 1093, three days after the deaths of her husband and eldest son. The cause of death was reportedly grief. She was buried before the high altar in Dunfermline Abbey in Fife, Scotland. In 1250, the year of her canonization, her body and that of her husband were exhumed and placed in a new shrine in the Abbey. In 1560, Mary Queen of Scots had Margaret's head removed to Edinburgh Castle as a relic to assist her in childbirth. In 1597, Margaret's head ended up with the Jesuits at the Scots College, Douai, France, but was lost during the French Revolution. King Philip of Spain had the other remains of Margaret and Malcolm III transferred to the Escorial palace in Madrid, Spain, but their present location has not been discovered.

Saint Margaret of Scotland is said to be the patron of Scotland, Dunfermline, Fife, Shetland, The Queen's Ferry, and Anglo-Scottish relations. I think the last could use a little more attention these days.

Maybe it's a good thing that AncestryDNA's latest revision puts my ancestry at 44% Scottish.

I've covered my three main uses of Facebook: relationships, writing platform, and news source. But there are several other minor uses, including:

- As a memory aid, a record of events. I use my own blog for this, but tend to use Facebook for more minor events.

Is Facebook the best or only tool for this use?

I could put them on my blog, or just not talk about them at all. For the primary purpose, a far more generally useful record of events can be found in my phone camera's time and location stamps.

- For making short comments on current events—individual, family, community, national, worldwide.

Is Facebook the best or only tool for this use?

Longer comments already go on my blog, but these are more conversation-style, the kind of thing I might say to Porter, or to friends over lunch. Facebook seems like a logical place for such tidbits ... but maybe not. When we talk with family and friends, we know with whom we are speaking and tailor our conversation accordingly. We have a pretty good idea when our comments will elicit support and agreement, and when they will poke the bear. Facebook, even when limited to our own friends list, covers a very wide variety of people, backgrounds, and opinions. I can get just about everyone in happy agreement by posting pictures of our grandchildren, or of my nephew's Boston Marathon race, but that's about it. Spontaneous, unguarded commentary posted on Facebook very often does not end well.

- Daily encounter with different points of view. My friends are nothing if not diverse in background, experience, and opinion. It's not that I need so much to hear their points of view, which are generally widely (if too loudly) available. What I value is the reminder that behind these worldviews, opinions, and attitudes are real human beings, fellow citizens of the world, men and women made in the image of God. People with parents, siblings, children, jobs, goals, dreams. No matter how ill-informed, twisted, and even evil I might find their opinions to be, these are people more like me than not, people of infinite value, and people I am actually commanded to love. And I try to present to Facebook a similar reminder to others that behind those whose opinions they consider ill-informed, twisted, and even evil there are also real human beings more alike them than not.

Is Facebook the best or only tool for this use?

It's hardly the best. Absolutely nothing replaces working together on a common project for opening one's eyes to the humanity of those with whom we disagree. I think the jury's still out on whether or not Facebook can do what I hope in this. It's risky—it's easy to do a lot of harm even with the best of intentions. But more and more as a society we are shutting ourselves into our own worlds of like-minded people and convincing ourselves of the "otherness" of those who disagree. The pandemic has only magnified the problem.

It may be too great a risk. I treasure stories of the lives and families of my Facebook friends. But these days I'm much more likely to hear political comments, usually negative and far too often painfully rude. I know what it's doing to my own mental health.

- Interesting and sometimes important bits of random information. My son-in-law finds a new product that he recommends. Shutterfly sends me a photo book offer. I've found Facebook often to be the best way to contact a company or organization, getting a rapid response from a Facebook message after several e-mails have gone unanswered. I often get church and choir information through Facebook that I don't get elsewhere. Friends send out everything from new baby announcements to urgent prayer requests through Facebook because it is a quick way to reach many people. Even the advertisers have learned that the best way to catch my attention is to offer a new recipe; I still curse the ads but I'm enjoying them more. Facebook also has saved me a few times by reminding me of birthdays.

Is Facebook the best or only tool for this use?

For some things, no. I can be reminded of birthdays through other ways. Companies like Shutterfly usually send e-mail offers as well as posting them on Facebook. There are more recipes on YouTube than I can handle anyway. However, there is no doubt that I will miss important information—such as the prayer requests—if I drop Facebook altogether. On the other hand, it seems that more and more people are moving to other social media sites, and it's going to take a very strong incentive to get me involved in another one—especially since they're not all going to the same places.

After weeks of pondering, I'm beginning to take action. But that will be for another post.

I wish any veterans reading this a blessed Veterans Day.

Permalink | Read 1474 times | Comments (0)

Category Social Media: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

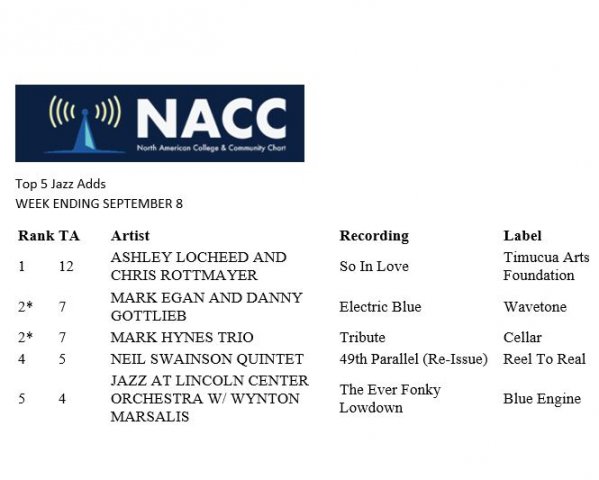

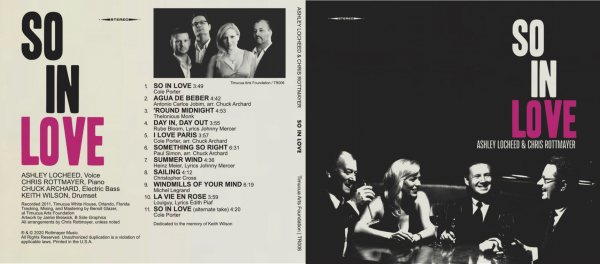

So In Love by Ashley Locheed and Chris Rottmayer (Timucua Arts Foundation 2020)

So In Love by Ashley Locheed and Chris Rottmayer (Timucua Arts Foundation 2020)

At this time in our country, rejoicing with those who rejoice and weeping with those who weep has left me an exhausted mess. Enter: music. I needed a non-political post and this is just the thing.

We've known Ashley for nearly 30 years, and her voice is as beautiful as ever.

I downloaded her album from Amazon. For the physical CD the price (at the moment) is better from her website. I'm told the album is also available on iTunes and other places I don't bother with.

You don't have to take my word for the quality of Ashley's singing. Here, here, here, and here are some reviews. And then there's this:

Congratulations, Ashley and Chris!

So, what just happened? As I’m writing, the election is still too close to call. There are still votes to count that could swing the election one way or the other. However, whoever ultimately wins, there are still some things we learned about the country on Election Day.

First, the pollsters were wrong. The vote in places like Florida and Pennsylvania looks like it’s out of the margin of error for most polls. I think this election marks the end of polls being taken seriously. Second, voting dynamics are changing. Along many ethnic lines, Trump made inroads where the Democrats thought they were secure. This showed in places like Florida and Texas. Third, the American people have handled themselves well so far. Only one major riot in the District of Columbia. It was my biggest fear that the election would be a nail-biter, which it is, and that the nation would be at its own throat. Thankfully, the latter has not happened. These three things say a lot about the nation.

The polls have lost the pulse of the American public. This means that new ways will have to be developed, or the system reformed. The polls are yet another domino to drop in the series of declining mainstream news organizations. All of these, with the exception of Fox, are very left-leaning, and that has been the key to their downfall. Once Trump goes away, whether that’s now or four years from now, what will they talk about? But the polls are not strictly partisan. After all, Fox said the same thing as everybody else. The failure two elections in a row shows that the system is flawed. It could be reimagined, but polls don’t work as they are now practiced.

We’ve also learned that the minority support that Democrats have had locked down since Lyndon Johnson is beginning to shift the other way. Of course, the majority of the minority vote is still going Democrat, but Trump’s minority support has helped a lot. The biggest example is Florida, which he won and in which many house seats are flipping red. This puts the House in play for the Republicans. These gains were seen in Texas and Florida. The exception was Arizona, where Trump lost, and where Latinos played a large role. This could fundamentally change the future if the trend continues. I think this represents a repudiation of the pandering the Democrats have shown towards the minority communities. It turns out that there are some in minorities who just want to be treated as Americans.

Lastly, and most importantly, the cities are all intact for the time being. No more riots in Philadelphia, none in Portland, Los Angeles still stands. It is of course possible that we could go to the Supreme Court, as Michigan and Wisconsin, upon whom the election stands, are both very close. Either side will do it; Trump has already said he will if he loses. I certainly hope that we can ride out the storm without burning American cities. It may be close, and I hope that the legal system is up to the task of detecting voter fraud. Such things may be tried in all of the remaining states, as dedicated supporters of either side try to make a last push. Both parties have built this election to be a titanic clash of good and evil, with the fate of not only the nation but of the earth and human race at stake. If you believe the rhetoric, surely saving the world is worth a little voter fraud? And if worth voter fraud, why not violence? I hope that the American public won’t buy into the rhetoric, and will prove themselves intelligent enough to realize that no matter who wins, the world won’t end.

Anything could still happen. But, whoever wins, we’ve seen some trends continue, with the failure of the polls. We’ve seen some new trends, with the shift in minority vote. And we’ve seen some trends stop, as almost no rioting has taken place. So, we have to wait and see where the votes fall, and where the inevitable legal case rules. It appears that the Republicans are going to win the Senate. The House and the Presidency are too close to call. It could be a Democratic victory, a Republican victory, or the status quo. We’d like to know more on the day after the election, but such is the world we live in.

[This is not the "Last Battle" series post I said would be next, but it seems appropriate. I'm still working on the other.]

As I write this post, the presidential election results are still up in the air, though the wind direction seems clear. It may change; it may not. Regardless, I will repeat below the post-election analysis I first wrote after Barack Obama's victory in 2008, and reprised in 2016 for Donald Trump's. The players and the parties change; the sense is the same.

And please remember this, victors, whoever you are: Approximately half of your fellow-countrymen—your neighbors, co-workers, friends, and families—are genuinely saddened, frightened, and maybe deeply depressed by the results. This is not some football game; it is our country, our world, and our future. Exulting in the streets, or anywhere other than among similarly-minded friends, is inappropriate. Whoever will eventually have been determined to have won the presidency, or any other office, this will not be a great triumph of good over evil. That battle can only be won in human hearts, and kindness and sympathy for those who are feeling disenfranchised might be a great place to begin.

Note: This was written specifically for a Christian audience. Anyone else is more than welcome to come along for the ride, but be prepared for a lot of quotations from a source of which you do not recognize the authority. You may still find value in the meaning.

How We Can Sing the Lord's Song in a Strange Land

By the rivers of Babylon we sat and wept

when we remembered Zion.

There on the poplars

we hung our harps,

for there our captors asked us for songs,

our tormentors demanded songs of joy;

they said, "Sing us one of the songs of Zion!"

How can we sing the songs of the LORD

while in a foreign land?

Psalm 137:1-4

First of all, we pick ourselves up with as much dignity as we have remaining and give respect and support to our new leaders. "Fear God, honor the king" (I Peter 2:17) applies in a democracy, too. Humor has an important place in discourse, but mean-spirited mockery does not. I'm extremely uncomfortable with the abuse heaped on George W. Bush, just as I was when it was Bill Clinton on the receiving end, and I will accord Barack Obama the respect due the President of the United States, as well as that due a human being created in the image of God.

We pray for Barack Obama, and for all "who bear the authority of government." If the Apostle Paul could write, per I Timothy 2:1-2, "I urge, then, first of all, that requests, prayers, intercession and thanksgiving be made....for kings and all those in authority, that we may live peaceful and quiet lives in all godliness and holiness," while living under the Roman Emperor Nero, we can do the same living under an elected president who is not likely to include among his alternative energy polices the burning of living, human torches.

We attempt to live our lives in the best, most honest, most noble, and most loving way possible. Back to I Peter again (2:15-16): "[I]t is God's will that by doing good you should silence the ignorant talk of foolish men. Live as free men, but do not use your freedom as a cover-up for evil; live as servants of God." The Republicans would do well to remember that scandal and wrong-doing among office holders has done more than anything else to bring them down. Granted, it's not fair that the Democrats mostly get a pass for their equal or greater sins—although it's actually a compliment that better behavior is expected of Republicans—but the reality is that Republicans were hurt badly first by misbehavior and even more by not visiting swift and sure justice upon the miscreants. To live purely and act rightly, with justice and love and in quiet confidence, will win more hearts than the most reasoned argument.

Do not repay anyone evil for evil. Be careful to do what is right in the eyes of everybody. If it is possible, as far as it depends on you, live at peace with everyone.... Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good. (Romans 12:17-18, 21)

Do everything without complaining or arguing, so that you may become blameless and pure, children of God without fault in a crooked and depraved generation, in which you shine like stars in the universe. (Philippians 2:14-15)

[L]et your light shine before men, that they may see your good deeds and praise your Father in heaven. (Matthew 5:16).

We attend to the wisdom of the serpent as well as the harmlessness of the dove. Now is not the time to retreat from the political process, but to be all the more involved that we might be alert to dangers that threaten what we hold dear, and to how we might best meet those threats. History has proven that when we are caught unaware we react hastily, badly, and often ineffectively.

We don't flee to the hills, or to another country (as many threatened after losing the 2000 and 2004 elections), or withdraw from the system in sulky silence. It's not time, yet, for "those who are in Judea to flee to the mountains." If we feel like exiles in our own land, it is time to remember what God said to his people at the time of another exile: "Build houses and settle down; plant gardens and eat what they produce. Marry and have sons and daughters; find wives for your sons and give your daughters in marriage, so that they too may have sons and daughters. Increase in number there; do not decrease. Also, seek the peace and prosperity of the city to which I have carried you into exile. Pray to the LORD for it, because if it prospers, you too will prosper" (Jeremiah 29:5-7). We continue to live our lives wisely and without fear. The administration may have changed, but the basic rules of life have not. There's still the Big Ten—don't steal, don't murder, don't mess with someone else's spouse, and all the rest—and the sound-bite version provided by Jesus: "Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind, [and] love your neighbor as yourself."

Many of us are accustomed to feeling alienated from the general American culture; it may even be easier—or at least clearer—when there's no pretense that "our guys" are in charge. Whether it's financial responsibility, ethical behavior, or wise decision-making, in a democracy the citizens get no better from their government than the majority lives out in their lives. True progress, then, requires that we balance a deliberate counter-cultural structuring of our own lives, families, and communities with a creative engagement of the larger culture. That is how we sing the Lord's song in a foreign land.

In August of 2018, my friend Eric Schultz posted an article that struck me to the heart, and I’ve been meaning ever since to write about the thoughts it inspired.

Warning to procrastinators: Don’t. Today I went to re-read the article and discovered that it was no longer available on Eric’s Occasional CEO site. Worse, though I thought I had saved copies of the article, it turns out they were merely copies of the link, which did me no good. Even the Wayback Machine failed me.

Eric found a draft version of the post and put it back up here. It’s not as polished as I remember the original being, but you’ll get the idea. In trying to fathom why it disappeared, he suggested that maybe he had decided it was too dark and took it down. Maybe he did—though having had one of my own posts removed from Facebook by the corporate censors, and heard similar stories from others, I no longer dismiss the notion that some disappearances might be less than innocent. In any case, dark as the post may have been, what I took away from it was hope.

For several years now I have been concerned by the number of people who look around and are overcome by despair. Despair deep enough that they have determined to have no children, because “how could I bring a child into such a terrible world?” If suicide is the extreme expression of individual hopelessness, surely this is the same attitude on a much larger scale.

The odd thing is, though they have this despondency in common, people are coming to this point from many different places, and with many different fears. Climate change, the election of President Trump, an asteroid hitting the earth, terrorism, pandemic, widespread civil unrest, and the takeover of our world by super-intelligent computers are only a few of the disasters on the brink of ending not only the world as we know it, but any world worth living in. How should we live in such times? How dare we bring children into such a world?

I’ve long wanted to write an answer to these questions—to these fears. Eric’s post gave me a place to start. The chief difference is that, back in 2018, when I started writing this post in my mind, it was from a position of strength. I saw these fears as understandable, but not really rational; I certainly didn’t feel them myself to any great extent. But this past year has dealt a hard blow to my easy optimism, and I sometimes fight with despair myself. I still believe in the hope I had back in 2018, and I think what I will write will not be substantially different from what I would have written then. The difference is that now I will also be preaching to myself.

This morning I realized that I have put this post off for so long not only because it's such an important subject that I don't feel worthy to take on, but even more because I was trying to make it into a single post, which it just cannot be. Therefore I’m going to be tackling it in smaller segments, and have created a new category for them: "Last Battle." At least that takes the pressure off of making everything hang together as a single narrative.

Next up? The hope I found in Eric’s dark essay.

Permalink | Read 1676 times | Comments (3)

Category Last Battle: [next] [newest]

Repeated emphasis on the importance of staying informed can easily trick you into thinking that endlessly consuming bad news on autopilot is a progressive moral duty, when in actuality it's the digital equivalent of emotional self-harm.

— Posted on Facebook by "Sara Z (@marysuewriter)," originally on Twitter, I think. I give credit where (as far as I can tell) credit is due, but a quick look at the original makes me not recommend it for reasons of language if nothing else. Nonetheless, this quote is spot on.

Permalink | Read 1316 times | Comments (1)

Category Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Lead Yourself First: Inspiring Leadership Through Solitude by Raymond M. Kethledge and Michael S. Erwin (Bloomsbury 2017)

Lead Yourself First: Inspiring Leadership Through Solitude by Raymond M. Kethledge and Michael S. Erwin (Bloomsbury 2017)

For me, the most impressive chapter of Cal Newport's Digital Minimalism was that on solitude, in which Newport recommends Lead Yourself First. It is a good book, filled with stories of how famous leaders of the past and present (both introverted and highly extroverted) found times of solitude essential to their success. If you've read the former, it is probably not necessary to read this one, Newport having done a good job of condensing the meat in his chapter. But the examples here, which include Dwight D. Eisenhower, Jane Goodall, T. E. Lawrence, Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, Aung San Suu Kyi, Winston Churchill, Martin Luther King, Jr., Pope John Paul II, and many lesser-known leaders, are worth reading in themselves. And for someone in a leadership position it might be even more inspiring.

I did find this to be a somewhat depressing book, despite my appreciation of its content. I find it impossible to read so much about what other people have accomplished and how they work without looking at my own life and thinking, how is it I never learned how to do this?

Somewhere in elementary school, one of my teachers expressed to my parents that he wished I had more interest in being a leader. Teachers are always looking for "leadership qualities." It never occurred to me to want to be a leader ... or a follower, either. So maybe that's where I missed out. Or maybe this is the equivalent of social media envy—the Barbie doll problem. Or maybe the answer lies in the first quotation.

Leading from good to great requires discipline—disciplined people who engage in disciplined thought and who take disciplined action. (from the forward by Jim Collins, p. xiv)

This book illustrates how leaders can—indeed must—be disciplined people who create the quiet space for disciplined thought and summon the strength for disciplined action. It is a message needed now more than ever, else we run the risk of waking up at the end of the year having accomplished little of significance, each year slipping by in a flurry of activity pointing nowhere. (p. xvii, emphasis mine)

I warned you it could be depressing.

To develop ... clarity and conviction of purpose, and the moral courage to sustain it through adversity, requires something that one might not associate with leadership. That something is solitude. (p. xviii)

Genuine leadership means taking the harder path. There are plenty of easier ones: the worn path of convention, smooth and obstacle-free; the fenced path of bureaucracy, where all the hard thinking is done for you, so long as you go wherever it leads; and the parade route of adulation, for those who elevate their followers' approval above all. To depart from any of these paths takes a considered act of will. Not because they are plainly right—more often the opposite is true—but because of the consequences that are sure to follow. The leader who defies convention must bear the disapproval of establishment types, who will try to coerce him morally, and failing that might box his ears. The leader who defies bureaucracy is usually in for harder treatment, as its machinery, given the chance, will run over him with the indifference of a tank. And the leader who makes unpopular decisions must be willing to be unpopular herself, at least for a while. (p. xix)

One of the book's strengths, I believe, is its recognition of what I will call active and passive solitude, and the importance of each. Passive solitude, a clearing of the thoughts commonly (though far from exclusively) associated with meditation, allows people to draw upon the intuition that is so often drowned out by the noise and action of everyday life. ("Be still, and know that I am God.") In active solitude one focusses intently on a particular problem—think Jacob wrestling with the angel. ("I will not let you go unless you bless me.")

The foundation of both analytical and intuitive clarity is an uncluttered mind. (p. 4)

For Eisenhower, the most rigorous way to think about a subject was to write about it. (p. 28)

[Quoting Eisenhower] My days are always full. Even when I think I have a couple of hours to myself, something always happens to upset my plans. But it's right that we should be busy—as long as we can retain time to think. (p. 29)

[Quoting Dena Braeger] We're getting more of everything, but less of what is authentically ourselves. If we spent more time alone, creating something that might not look as amazing [as something from Pinterest] but is more authentic, we'd value ourselves more. (p. 58)

[Quoting Chip Edens] Leaders experience fear in times of turbulence or threat. You become obsessed about worst-case scenarios, fall into despair. That's the easiest way to resolve the conflict. That's when people snap—they quit the job, the marriage is ended, there's no hope. You need to step away from that and give yourself space to process it. (p. 66, emphasis mine)

[Quoting Chip Edens] Differences are a product of ideas. Division is a product of behavior. A community means we live together with differences, but we can't be divided. (p. 66)

[Quoting Dena Braeger] People are so quick to bow to the idea of "staying connected." They aren't conscious of the priorities they're setting with regard to their time. Time is an unrenewable resource. You can't get it back. All these things we've done to exchange information, to access information at our fingertips, have actually taken away our time for restoring the soul. (pp. 133-134)

Solitude has been instrumental to the effectiveness of leaders throughout history, but now they (along with everyone else) are losing it with hardly any awareness of the fact. Before the Information Age—which one could also call the Input Age—leaders naturally found solitude anytime they were physically alone, or when walking from one place to another, or while standing in line. Like at great wave that saturates everything in its path, however, handheld devices deliver immeasurable quantities of information and entertainment that now have virtually everyone instead staring down at their phones. Society did not make a considered choice to surrender the bulk of its time for reflection in favor of time spent reading tweets or texts. (p. 181)

A leader must strike a balance between solitude and interaction with others, but leaders (along with everyone else) face considerable social pressure to skew the balance toward interaction. The term "loner" is usually a pejorative, often directed at people who spend only a fraction of their time alone. And in many offices the culture is to gather in herds—not only in meetings but at cake parties, lunch, and various events outside work. ... This same culture also finds physical manifestation, in open-office plans and large rooms full of cubicles. (p. 182)

If you plan to use solitude to think about a specific issue, you should identify that issue in advance and briefly review any materials you think especially relevant. That will get your mind processing the issue beforehand, which often allows insights—sometimes analytical, sometimes intuitive—to come more quickly when you do think about it. (pp. 184-185)

Extroverts gain energy from interaction with others, while introverts lose it. And introverts gain energy from solitude, while extroverts lose it. ... But these energy transfers have little to do with how extroverts and introverts actually perform in these settings. Introverts can excel in social settings; extroverts can excel at thinking alone. The limitation is simply that members of each group can spend only so much time out of their element before they need to recharge. (p. 185)

In some quarters there is a "fear of missing out": a fear that, if one unplugs from e-mail or news services or social media even for a few hours, they'll be less current (a few hours less, to be exact) than their peers. And indeed that is true. But tracking all these inputs is surrender to the Lilliputians. One simply cannot engage in anything more than superficial thought when cycling back and forth between these tweets and work. And most of the inputs are piecemeal, and thus worthless anyway. As with our obsession with smartphones, one needs to make a choice about whether to engage in this kind of practice. And no one serious about his responsibilities will choose to engage in it. (p. 186)

Here's a 15-minute TED talk by Raymond Kethledge that will give you another taste of these ideas.

I would just add two comments.

(1) The quote he attributes to Viktor Frankl at about 10:10 is probably not by him (see this discussion), not that that devalues the point.

(2) At about 11:00 he states, "Moral courage is what we need when we're subject to moral criticism. Moral criticism is when someone says, 'You're not simply mistaken because of what you believe or what you choose to do, but ... you're a bad person because of those things.'" That, ladies and gentlemen, sums up the problem with discourse today.

What we didn't realize at the time, and I as a seminarian certainly didn't realize, was that by participating in the Liturgy, even if we didn't get it at first, even if we didn't want to be there at 9 a.m. on Sunday morning in our stalls, if we participated in the Liturgy it would profoundly change us.

Fr. Trey Garland, on being in choir with Dr. Robert Delcamp

Sunday November 17, 2019

American Guild of Organists Hymn Festival

Episcopal Church of the Resurrection, Longwood, Florida

Permalink | Read 1240 times | Comments (0)

Category Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Today we tried to vote by mail. Florida has already proved that it handles that well, but just to be on the safe side, we had planned to use the ballot drop box at our local library, which is an early voting site.

For the record, on principle I don't like early voting, and would rather use mail-in voting only when I'm out of town for Election Day. But with this being such an important election, and figuring that the odds were higher in this year than most for something cropping up to prevent our getting to our local polling place on November 3, voting early seemed the better part of valor.

Here's the warning I promised in the title: Mark your ballot clearly, but don't go overboard. I filled out the first page of my ballot neatly with a fine-point black Sharpie, which seemed to be doing a good job—until I turned the page over to fill in the other side. The ink had bled through from the first side, making the second side full of those "stray marks" we are always warned against. Rather than get a new mail-in ballot, we decided to vote in person.

Porter stood at the end of the line while I took care of my business with the library itself. That took longer than expected, so I thought he would have made a lot of progress, but that was far from the case. However, he had learned about another early voting place that was reputed to be not as crowded, and was near my favorite GFS foodstore and on the way to picking up our car from getting its faulty airbag replaced ... so that's what we did.

The voting went smoothly: there were lots of people, but it was a big room efficiently run, so there was almost no waiting. They cancelled our mail-in ballots, had us sign in on the screen with these cute little disposable "pens" that looked suspiciously like fancy Q-Tips, and gave us sanitized pens for filling in our ballots.

I really do feel more comfortable watching my votes be recorded right then and there. And I'm glad to have gotten the job done.

But if you're going to vote by mail, do be careful what kind of pen you use.