According to this article,

During an interview on CNN's "State of the Union," [CDC director Rochelle] Walensky was asked about vaccinated Americans who have contracted the virus—and whether anyone has died from an infection, despite being inoculated. Walensky said the CDC is aware of 223 so-called "break-through" infections in vaccinated Americans, but clarified that many of those individuals died due to other causes. "Not all of those 223 cases who had COVID actually died of COVID," she said. "They may have had mild disease but died, for example, of a heart attack."

This makes perfect sense to me. From the beginning of this pandemic, I have been frustrated by seeing a clear tendency to report all deaths in anyway associated with COVID-19 as caused by the virus. Witness the testimony of a friend of ours, a nurse, who (in another state) was ordered to count as new, active COVID-19 cases anyone who tested positive for the COVID-19 antibodies—which meant that many cases were counted multiple times. And that of an Emergency Medical Technician I know who only partially joked, "If someone with COVID-19 is run over by a truck, his death is counted as a COVID-19 death." Then there's the death I know about that was put down as due to COVID-19 but should have been "nursing home neglect." Of course these are isolated examples, but good luck trying to convince me that they aren't representative of widespread mis-information.

What it comes down to is this: What are you trying to prove?

When the powers-that-be were trying to justify elaborate and invasive regulations in reaction to the pandemic, it was to their advantage that the numbers be as large as possible. But when the object is to reassure the public of the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, the advantage lies in giving the virus no more blame than is absolutely undeniable.

I happen to believe that the CDC is closer to the truth in the case of the vaccine, but that's not the point. What's important is that with every report, every news story, every rumor,

Always, always, always ask, Cui bono?

Who benefits? What are they trying to prove? Follow the money.

This is the post I started to write five months ago, but postponed to make sure everyone involved got through their quarantines and other impedimenta successfully.

I like to think that we've been more careful than most during this pandemic, though more due to the concern of our children (who apparently think we are "old") than our own. But when you're retired, and introverted, and not easily bored, staying home is a pretty easy option. We wore masks before our county made them mandatory, shopped only for what we deemed necessities, and used the stores' "senior hours" when we could. I'm also the only person I know who consistently washed (or quarantined) whatever we brought home.

But all that isolation, particularly the lack of physical touch, is hard even on introverts.

Hardest of all was cancelling our big family reunion scheduled for April 2020—coinciding with what was supposed to be the first visit home in six years of our Swiss family. Following close behind were missing our nephew's wedding, our normal summertime visit to the Northeast, and our long tradition of a huge family-and-friends Thanksgiving week of feasting and fun, all of which would have involved being with most of our American-based family. Plus the breaking my fourteen-year streak of travelling overseas to visit our expat daughter and her family (one year to Japan, thirteen to Switzerland).`

I know that doesn't begin to compare with the hardship endured by those who were forceably separated from loved ones who were sick or dying. But when the "temporary measures to keep our hospitals from being overwhelmed" turned into unending months of restrictions—with our hospitals so far from overcrowded as to be financially strapped due to underutilization—even normally compliant people like us began to chafe.

Even as we relaxed and let go of much of our fear, we remained vigilant in our precautions, for a very good reason: a light, not at the end of the tunnel, but a much-needed illumination in the middle of the tunnel. We needed to stay healthy, because...

The reunion remained off the table, due to onerous quarantine requirements imposed by the states the rest of our family live in. But thanks to much work on their part, and a state government more enlightened than most, our European family was able to visit us in December. Rarely have I been so happy to be living in Florida, which welcomed them with open arms. So of course did we! Mind you, I think the CDC was still recommending we wear masks all the time with visitors and stay six feet apart, but naturally that didn't last six seconds! A year apart from family is far too long, and that goes tenfold for grandchildren. Sometimes you just do what you have to do.

We did the risk/benefit analysis—and made the joyful choice.

Porter had to drive to Miami to pick them up, because so many flights had been cancelled. But he would have driven farther than that to bring them home!

We had been prepared to stay mostly around the house, just enjoying each other's presence. And at first we did a lot of that, since merely being in America was adventure enough for the grandkids. But they were here for a month, and most of the tourist attractions had reopened, albeit at reduced capacity, so we took full advantage.

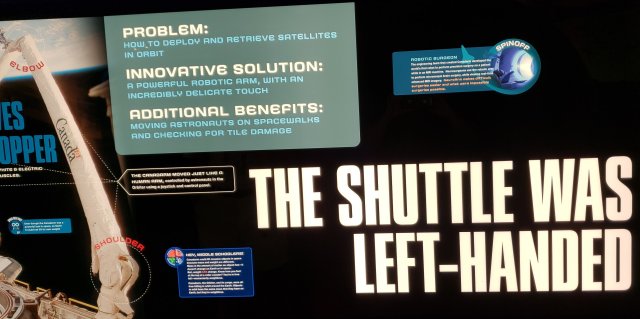

Kennedy Space Center was amazing. We were not the only visitors in the park, but at times it seemed like it. Sadly, some of the attractions were still COVID-closed, but there was certainly plenty to see. The following photo is for the lefties in our family:

One of the trips I enjoyed the most was to Blue Spring State Park, which was visited by more manatees than we've ever seen naturally in one place. The weather was perfect—that is, cold. Cold weather drives the manatees from the ocean and the rivers into the relatively warm water (about 72 degrees) of the springs. The air temperature made most of us keep our masks on even though that was not required except inside the buildings, since we discovered them to be very effective nose-warmers.

Another favorite activity was swimming. (Not with the manatees; that's no longer allowed.) The intent was for most of it to be in our own pool, and indeed it was, but there had been a glitch: We purchased a pool heater, knowing that our pool temperatures in December can dip into the 50's (Fahrenheit). However, the unit that was supposed to have been installed before our guests arrived was delayed again and again. Whether it was actually the fault of the pandemic is anyone's guess, but that's what took the blame. It finally arrived just a few days before they had to return to Switzerland. Until then, the children swam bravely, if not at length, in the cold water, and all of us enjoyed the (somewhat) heated pool at our local recreation center. And then they really appreciated our own heated pool for those last few days.

To be continued....

Permalink | Read 1489 times | Comments (1)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

This may explain a few marital frustrations. (Credit to someone on Facebook but I can't find it again to share it.)

Permalink | Read 1390 times | Comments (3)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The Wild Robot and The Wild Robot Escapes by Peter Brown (Little, Brown 2016, 2018)

The Wild Robot and The Wild Robot Escapes by Peter Brown (Little, Brown 2016, 2018)

When everyone in the house (adult, 17, 14, 12, 10, 8, and 6) approves of a book, I generally find it worth looking into, despite my well-ingrained—and more often than not justified—prejudice against recently-written children's books. Peter Brown's Wild Robot books were definitely worth the reading.

Brown's story of a robot cast away on an uninhabited (by humans) island and how its programming directs its adjustment there, and in later adventures, is very well done, reminding me of Isaac Aimov's treatment of the practical and ethical issues of a society that includes multitudes of robotic machines.

There's love and conflict and tragedy and emotional struggles, all handled sensitively. I can't say I like these books better than S. D. Smith's Green Ember series, which my readers know I love greatly, but they are less dark—and less violent, despite some scary adventures. I detected no warning bells for my very sensitive grandchildren on the other side of the family. They may especially enjoy that the main character is female (if one can say that about a robot) who is strong and smart, gentle and motherly.

Sure, I could make some complaints, but they're minor and overshadowed by the good.

So ... Canada is now saying, "It's not as bad here as in North Korea, or Nazi Germany." And we can say, "It's not as bad here as in Canada." Not exactly progress, is it?

As a mathematician I can say it is, actually—with a minus sign.

That was from May 7. Today we have this.

This is not sensationalism and fearmongering. Viva Frei is careful to see many sides of an issue. So am I, and I fully acknowledge that not everyone sees the same line separating civil disobedience from selfish thuggery.

Following the rules is necessary for a functional civilization.

Blindly following the rules is necessary for a functional tyranny.

Respecting one another is necessary for a functional humanity.

I'm going to leave it at that for now.

I really don't like the way Mother's Day has been altered, morphing from a joyous celebration of and respect for our own mothers, to honoring all women who happen to be mothers, to making the day downright depressing by including everyone under the sun and telling many sad stories in the process. At every step the day seems to have become less meaningful and more selfish.

But in this world there are still plenty of sorrows associated with motherhood, and that suffering needs to be remembered. This was brought home again to me when I read this in The Wild Robot, by Peter Brown.

Do you know what the most terrible sound in the world is? It's the howl of a mother bear as she watches her cub tumble off a cliff.

This post is for every mother who has lost a child: at any age; at any stage of life; suddenly or through prolonged suffering; by accident, injury, illness, stillbirth, miscarriage, or abortion; and also for those who have lost even the hope and dream of children.

Even more so, this post is for mothers (and fathers) who have heard the howls of their own children who have suffered these losses.

Sunday is for celebrating what we have. Today we can pause to think about what we—or more importantly, others—have not.

Permalink | Read 1281 times | Comments (1)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

A Child's History of England by Charles Dickens (public domain, 1851-1853)

A Child's History of England by Charles Dickens (public domain, 1851-1853)

Dickens' book is, unsurprisingly, in the public domain. I read the free Kindle version and it was fine, though it might be worth springing for another $2 and getting the original illustrations as well.

A Child's History of England is a maddening book, yet a valuable one. According to its Wikipedia article, it "was included in the curricula of British schoolchildren well into the 20th century." It never could be now—which may be an indication that it should be. It is one man's very biased view of English history, hence valuable to balance other biases.

What's good about it? Well, I appreciated the organized layout of English history from ancient times up to the reign of William and Mary, with a very quick summary thence to Queen Victoria. Bit by bit, through several sources, I am gaining knowledge of the history of the lands that were home to many of my ancestors and played a significant part in the development of Western Civilization. The book, being designed for intelligent children, is both readable enough and interesting enough to read much more like a story than a textbook.

What didn't I like? To begin with, it is obviously and admittedly a propaganda piece. Dickens himself said of his book,

I am writing a little history of England for my boy ... For I don't know what I should do, if he were to get hold of any conservative or High Church notions; and the best way of guarding against any such horrible result is, I take it, to wring the parrots' neck in his very cradle.

Dickens does not appear to have liked England very much. He praises the Saxons, and holds Alfred the Great in very high esteem. Henry V wasn't too bad, and Oliver Cromwell gets too much credit for not being as horrible as the kings that preceded and followed him. Other than that, Dickens doesn't seem to have much respect for any of the British monarchs and their hangers-on. He also passionately hates the Catholic Church, and much of the undivided Church itself before the Reformation. The Puritans are heaped with scorn as well. He clearly claims to be a Christian, just as he claims to be an Englishman, but doesn't seem to care much for either Christianity or England. Sometimes the book feels less like a history and more like a series of ad hominem attacks. He even manages to draw a caricature of Joan of Arc as a mentally deficient peasant girl abused for others' gain.

Part and parcel of his prejudice, I believe, his his annoying habit of inconsistently referring to people sometimes by name, sometimes by title, often by nickname, and even by insult. I found this to make keeping the characters straight difficult, and I tired of flipping back several pages to try to figure out which particular duke was currently meant. It certainly doesn't help me to remember that he's talking about King James I when most of the time Dickens refers to him as "His Sowship."

For all that, I do recommend reading A Child's History of England, though only in the context of competing viewpoints. It does a good job of helping to put together the pieces of the complex puzzle that is the story of England.

"Who Is in Control? The Need to Rein in Big Tech," from this past January's Imprimis magazine, deserves mention here. It's not one I would normally republish, not because I don't agree with it, but because the author is the senior technology correspondent for Breitbart News. He has the credentials to be heard, but Breitbart's biases make me as wary as CNN's do, and I know many of my left-leaning readers would see that and stop reading.

Don't. Please don't. What he has to say about the uncontrolled power of Google, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Amazon, and the like should concern everyone. Right now, it's conservatives who are feeling the flex of Big Tech's muscles, but the tech leaders could easily turn around and bite the hands that are currently feeding them. If you believe in freedom and democracy at all, this is worth reading and pondering.

Like most Europeans, my son-in-law, who is Swiss as well as American, has always wondered why I am so afraid of the misuse of governmental power, and not concerned about Google. I, in turn, don't understand how he can be so worried about tech companies while having no problem with a level of government surveillance and interference that would shock most Americans. I still think he's wrong not to be worried about excessive power in governmental hands, but I have to admit that he's right about Big Tech.

My response used to be, "Who cares if Google uses my data to target ads? I just ignore them, as I've always done with ads in newspapers (I usually don't even notice them) and on television." But that was then. That was before Facebook took down my 9/11 memorial post because it included a photo of Saddam Hussein. That was before it became obvious that Facebook was troubled by posts that even hinted that they might be about COVID-19. (Click image to enlarge.)

That was before I noticed how much Facebook and YouTube censor viewpoints they don't like. How careful one must be not to run afoul of their "algorithms." And certainly before Facebook, Twitter, Google, and Amazon proved that they are powerful enough to shut down the president of the United States, as well as a service (Parler) that welcomed Donald Trump's participation.

This may look as if it's about politics. It's not. It's about power. And it threatens everyone on every part of the political spectrum.

In January, when every major Silicon Valley tech company permanently banned the President of the United States from its platform, there was a backlash around the world. One after another, government and party leaders—many of them ideologically opposed to the policies of President Trump—raised their voices against the power and arrogance of the American tech giants. These included the President of Mexico, the Chancellor of Germany, the government of Poland, ministers in the French and Australian governments, the neoliberal center-right bloc in the European Parliament, the national populist bloc in the European Parliament, the leader of the Russian opposition ... and the Russian government.

Common threats create strange bedfellows. Socialists, conservatives, nationalists, neoliberals, autocrats, and anti-autocrats may not agree on much, but they all recognize that the tech giants have accumulated far too much power. None like the idea that a pack of American hipsters in Silicon Valley can, at any moment, cut off their digital lines of communication.

It is important to remember that the Web, as we know it today—a network of websites accessed through browsers—was not the first online service ever created. In the 1990s, Sir Timothy Berners-Lee invented the technology that underpins websites and web browsers, creating the Web as we know it today. But there were other online services, some of which predated Berners-Lee’s invention. Corporations like CompuServe and Prodigy ran their own online networks in the 1990s—networks that were separate from the Web and had access points that were different from web browsers. These privately-owned networks were open to the public, but CompuServe and Prodigy owned every bit of information on them and could kick people off their networks for any reason.

...[T]he Web was different. No one owned it, owned the information on it, or could kick anyone off. That was the idea, at least, before the Web was captured by a handful of corporations.

We all know their names: Google, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Amazon. Like Prodigy and CompuServe back in the ’90s, they own everything on their platforms, and they have the police power over what can be said and who can participate. But it matters a lot more today than it did in the ’90s. Back then, very few people used online services. Today everyone uses them—it is practically impossible not to use them. Businesses depend on them. News publishers depend on them. Politicians and political activists depend on them. And crucially, citizens depend on them for information.

Ah, the early days. We were early Prodigy users, and GEnie, before the Internet took off. Those were the days when it was easy to interact with famous people, because it was all so new and the numbers were small. GEnie's Education RoundTable was a great resource in our early days of homeschooling, and there I met Bobbi Pournelle, wife of science fiction writer Jerry Pournelle. We even arranged to meet when she came to Orlando, as did other of my ERT acquaintances. That was before we were warned against having meet-ups with people we only knew online, and it was a good deal of fun.

Big Tech has become the most powerful election-influencing machine in American history. It is not an exaggeration to say that if the technologies of Silicon Valley are allowed to develop to their fullest extent, without any oversight or checks and balances, then we will never have another free and fair election. But the power of Big Tech goes beyond the manipulation of political behavior. As one of my Facebook sources told me ... “We have thousands of people on the platform who have gone from far right to center in the past year, so we can build a model from those people and try to make everyone else on the right follow the same path.” Let that sink in. They don’t just want to control information or even voting behavior—they want to manipulate people’s worldview.

Consider “quality ratings.” Every Big Tech platform has some version of this, though some of them use different names. The quality rating is what determines what appears at the top of your search results, or your Twitter or Facebook feed, etc. It’s a numerical value based on what Big Tech’s algorithms determine in terms of “quality.” In the past, this score was determined by criteria that were somewhat objective: if a website or post contained viruses, malware, spam, or copyrighted material, that would negatively impact its quality score. If a video or post was gaining in popularity, the quality score would increase. Fair enough. Over the past several years, however—and one can trace the beginning of the change to Donald Trump’s victory in 2016—Big Tech has introduced all sorts of new criteria into the mix that determines quality scores. Today, the algorithms on Google and Facebook have been trained to detect “hate speech,” “misinformation,” and “authoritative” (as opposed to “non-authoritative”) sources. Algorithms analyze a user’s network, so that whatever users follow on social media—e.g., “non-authoritative” news outlets—affects the user’s quality score. Algorithms also detect the use of language frowned on by Big Tech—e.g.,“illegal immigrant” (bad) in place of “undocumented immigrant” (good)—and adjust quality scores accordingly. And so on.This is not to say that you are informed of this or that you can look up your quality score. All of this happens invisibly. It is Silicon Valley’s version of the social credit system overseen by the Chinese Communist Party. As in China, if you defy the values of the ruling elite or challenge narratives that the elite labels “authoritative,” your score will be reduced and your voice suppressed. And it will happen silently, without your knowledge.

If Big Tech’s capabilities are allowed to develop unchecked and unregulated, these companies will eventually have the power not only to suppress existing political movements, but to anticipate and prevent the emergence of new ones. This would mean the end of democracy as we know it, because it would place us forever under the thumb of an unaccountable oligarchy.

The author does have a suggestion, and I think it sounds reasonable. (I know my audience will not hesitate to let me know if I've missed something.) Some may think that I am against government regulation, but that's not true. I'm against unreasonable government regulation. (For my purposes, I get to define "unreasonable.") Most especially I am against regulations that fail to distinguish between large entities (in business, agriculture, education, medicine, and the like) and the small and individual. I don't know how to quantify "large enough" to need special regulation, but I have no doubt that our tech giants have crossed that line.

All of Big Tech’s power comes from their content filters—the filters on “hate speech,” the filters on “misinformation,” the filters that distinguish “authoritative” from “non-authoritative” sources, etc. Right now these filters are switched on by default. We as individuals can’t turn them off. But it doesn’t have to be that way. The most important demand we can make of lawmakers and regulators is that Big Tech be forbidden from activating these filters without our knowledge and consent. They should be prohibited from doing this—and even from nudging us to turn on a filter—under penalty of losing their Section 230 immunity as publishers of third party content. This policy should be strictly enforced, and it should extend even to seemingly nonpolitical filters like relevance and popularity. Anything less opens the door to manipulation.

I cannot say it strongly enough: This is not a left-wing thing; this is not a right-wing thing. This is a big thing. A thing we must all come to grips with.

It has been a hard year with singing in church choir forbidden. I think that decision was a huge mistake, but our leaders are flying by the seat of their pants here and I'm not going to argue about it now. They're all doing what they think best, even if I disagree with it. But it has certainly been a great loss.

At times like this it is lovely to be part of a family large enough to include all voice parts. In December we were blessed to have a hymn fest with one set of grandchildren, and in April with the other. Call it our Christmas and Easter Festival Celebrations.

Of course we had to include our family anthem: St. Patrick's Breastplate. Nine verses, including two rarely sung these days. (Only a small excerpt here.) Glory, glory, hallelujah!

I realize that for very few of my readers is the question of whether or not a pregnant woman should get a COVID-19 vaccine of any importance. Nonetheless this is worth a post just because it is one of those laugh-or-cry articles.

The source is the School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins, which I generally respect. Here's a link to the whole article for those of you who seriously want the information. It's a serious business and an important decision to make.

For everyone else, however, here are a few snippets that caught my eye and inspired me to write. The bolded emphasis is my own.

Globally, over 200 million people are pregnant each year. Whether they should be offered the new COVID vaccines as they become available is an important public health policy decision. Whether pregnant people should seek vaccination is a deeply personal decision.

Note the term "pregnant people." The article goes out of its way, to the point of being very annoying, to avoid the term, "pregnant women." Exactly how many pregnant men have there been in the history of the world? I do, however, appreciate the acknowledgement that it's a personal decision, although later on the article seems to find a problem with that.

Evidence to date suggests that people who are pregnant face a higher risk of severe disease and death from COVID compared to people who are not pregnant. For instance, pregnant people are three times more likely to require admission to intensive care and to need invasive ventilation. The overall risk of death among pregnant people is low, but it is elevated compared to similar people who are not pregnant. Some studies suggest that COVID in pregnancy might be associated with increased rates of preterm birth.

There are still significant unknowns: How do risks vary by trimester? What are the risks of asymptomatic infection? Further, most current information about COVID and pregnancy comes from high-income countries, limiting its global generalizability.

Although there is not yet pregnancy-specific data about COVID vaccines from clinical trials, the vaccines have been studied in pregnant laboratory animals. Called developmental and reproductive toxicity (DART) studies, research with pregnant animals can provide reassurance about moving forward with vaccine research in pregnant people.

All three of these vaccines offer a very high level of protection against severe COVID. There is little reason to believe these vaccines will be less effective in pregnant people than they are in people of comparable age who are not pregnant.

The next sentence is the one that made me sure I had to write about this. It's the kind of thing I would have shared on Facebook, except that I'm trying to reduce my Facebook presence, so it goes here instead. With more words, naturally.

Professional societies, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Society for Maternal-Fetal-Medicine, and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, all support COVID vaccination in pregnancy when the benefits outweigh the risks.

What, pray tell, does that say that has any usefulness? Who in his right mind would support something when the risks outweigh the benefits? So how is this a meaningful statement at all?

The absence of pregnancy-specific data around COVID vaccines continues an unfair pattern in which evidence about safety of new vaccines for pregnant people lags behind. This unfairness is ethically problematic in at least two important ways.

So, it's unfair because we don't have enough data on the effects of the vaccines in pregnancy? Would they have held back the vaccines until sufficient data had been gathered so that the information was "equal" for everyone? That would truly have been unfair to pregnant women, because letting the rest of the population get vaccinated helps them whether or not they feel safe getting the vaccine for themselves.

First, people may be denied vaccine, or may face barriers in accessing vaccine, because they are pregnant.

I agree that's a problem. Because the data is insufficient, in absence of a clear danger to mother and/or child in getting the vaccine, it should not be withheld from a woman who feels comfortable with it.

Second, even when pregnant people are eligible for vaccination, because public health authorities have not explicitly recommended COVID vaccines in pregnancy, the burden of making decisions about vaccination has shifted to pregnant people.

And where else should it be? Medical advice should not be handed down like commandments from heaven. People need the best information available, and the freedom to make their own decisions—even wrong ones.

Come to think of it, even commandments from heaven come with the free will to ignore them.

Permalink | Read 1378 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Thinking further about Cal Newport's Deep Work, here are two more valuable quotations I should have included.

First, on the importance of a "shutdown ritual" for ending the "work day" (however that is defined for us) and not letting it take over the rest of our lives. I see it as less about employment and more about being able to switch cleanly from one activity to another (including rest).

The concept of a shutdown ritual might at first seem extreme, but there's a good reason for it: the Zeigarnik effect. This effect ... describes the ability of incomplete tasks to dominate our attention. It tells us that if you simply stop whatever you are doing at five p.m. and declare, "I'm done with work until tomorrow," you'll likely struggle to keep your mind clear of professional issues, as the many obligations left unresolved in your mind will, as in Bluma Zeigarnik's experiments, keep battling for your attention throughout the evening.

At first, this challenge might seem unresolvable. As any busy knowledge worker can attest, there are always tasks left incomplete. The idea that you can ever reach a point where all your obligations are handled is a fantasy. Fortunately, we don't need to complete a task to get it off our minds. ... In [a study by Roy Baumeister and E. J. Masicampo], the two researchers began by replicating the Zeigarnik effect in their subjects (in this case, the researchers assigned a task and then cruelly engineered interruptions), but then found that they could significantly reduce the effect's impact by asking the subjects, soon after the interruption, to make a plan for how they would later complete the incomplete task. To quote the paper: "Committing to a specific plan for a goal may therefore not only facilitate attainment of the goal but may also free cognitive resources for other pursuits."

The shutdown ritual ... leverages this tactic to battle the Zeigarnik effect. While it doesn't force you to explicitly identify a plan for every single task in your task list (a burdensome requirement), it does force you to capture every task in a common list, and then review these tasks before making a plan for the next day. This ritual ensures that no task will be forgotten: Each will be reviewed daily and tackled when the time is appropriate. Your mind, in other words, is released from its duty to keep track of these obligations at every moment—your shutdown ritual has taken over that responsibility. (pp. 152-154, emphasis mine).

I find I need to re-learn the following every day.

The science writer Winifred Gallagher stumbled onto a connection between attention and happiness after an unexpected and terrifying event, a cancer diagnosis. ... [A]s she walked away from the hospital after the diagnosis she formed a sudden and strong intuition: "This disease wanted to monopolize my attention, but as much as possible, I would focus on my life instead." The cancer treatment that followed was exhausting and terrible, but Gallagher couldn't help noticing, in that corner of her brain honed by a career in nonfiction writing, that her commitment to focus on what was good in her life—"movies, walks, and a 6:30 martini"—worked surprisingly well. Her life during this period should have been mired in fear and pity, but it was instead, she noted, often quite pleasant. Her curiosity piqued, Gallagher set out to better understand the role that attention—that is, what we choose to focus on and what we choose to ignore—plays in defining the quality of our life. After five years of science reporting, she came away convinced that she was witness to a "grand unified theory" of the mind:

Like fingers pointing to the moon, other diverse disciplines from anthropology to education, behavioral economics to family counseling, similarly suggest that the skillful management of attention is the sine qua non of the good life and the key to improving virtually every aspect of your experience.

This concept upends the way most people think about their subjective experience of life. We tend to place a lot of emphasis on our circumstances, assuming that what happens to us (or fails to happen) determines how we feel. From this perspective, the small-scale details of how you spend your day aren't that important, because what matters are the large-scale outcomes, such as whether or not you get a promotion or move to that nicer apartment. ... [D]ecades of research contradict this understanding. Our brains instead construct our worldview based on what we pay attention to. If you focus on a cancer diagnosis, you and your life become unhappy and dark, but if you focus instead on an evening martini, you and your life become more pleasant—even though the circumstances in both scenarios are the same. As Gallagher summarizes: "Who you are, what you think, feel, and do, what you love—is the sum of what you focus on." (p. 76-77, emphasis mine).

I don't write these posts to frighten or depress anyone. But a number of my readers have higher priorities than chasing down news stories, so I like to raise awareness when I come upon something important, interesting, or even just fun. This one's not fun, but it is important.

Why should I care what's happening in Canada? Leave aside for the moment that Canadians, too, are human beings made in the image of God and therefore we should care about them, and that Canada is the huge neighbor covering our entire northern border and one of our major allies. We should also care about what's happening with our near neighbor because the United States is not as far from this creeping danger as we might like to think.

One of our daughters and several of our grandchildren have for years been taking lessons in karate. One thing I have learned from them is that the first, and possibly the most important, key to self-defense is awareness of your surroundings. Never forget that a far better source also proclaimed wisdom as an essential accompaniment to innocence.

Half a century ago our family discovered Ontario's Arrowhead Provincial Park. We had only intended to spend one night there on our way to Michigan, but were so enchanted we stayed for three. It was quite primitive at the time: there wasn't much to do, and the bathroom "facilities" were a latrine. But we were almost alone in the park; most of the other tourists were staying in nearby Algonquin Provincial Park, which was more developed and very popular. Never have I breathed air so clean and invigorating. More memorable than that, however, were the stars. Not in all the rest of my life have I seen such a display, and such a show, as we lay on our backs on a huge woodpile and watched shooting stars streak across the sky at a rate of perhaps one every two or three minutes. I knew then that if I couldn't live in the United States, I'd want to go to Canada. Later Switzerland moved ahead, and that was well before we had family living there. But Canada stayed a solid second.

Well, that was then and this is now. There are many reasons why Canada has slipped far down on my list, but the following video would be enough.

A government (Ontario's, in this case) went too far with its pandemic restrictions, and finally the citizens—including medical practitioners and the police—rebelled, forcing the leaders to back down on the most egregious of the new rules. That's good news, but be sure to watch to the end to see the clips of Ontario's authorities and their "this hurts me more than it hurts you but it's for your own good" act. And their "it's your duty to snitch on your neighbors" response.

Ontario is a province of 14.5 million people, and 650 of them are currently in intensive care units. This minuscule percentage has caused such panic that the provincial government's response was (among other things) to issue a stay-at-home order, to close playgrounds, boat ramps, and other outdoor recreational activities, and to authorize law enforcement to stop and interrogate any people caught outside of their homes. Canada takes enforcement of these rules very seriously: the fine for violating Quebec's 8 p.m. to 5 a.m. curfew, for example, starts at $1500.

Part of the problem is that Canada's health infrastructure is not good. An ordinary flu season overwhelms the ICUs. I've known for years that Canada's healthcare system is broken, despite the fact that it has its passionate defenders. (Much of my information comes from Canadian nurses, who fled to the U.S., bringing horror stories with them.) Even a bad system—healthcare, government, business, church, marriage—can look reasonable when times are good. It's times of crisis, pressure, and stress that reveal the truth and call into account the leaders we have elected (or been saddled with).

I used to look at historical happenings in other countries—e.g. Austria-Hungary 1914, pre-WWII Germany, Communist Eastern Europe, the Rwandan genocide—and smugly think, "That could never happen here, not now." However, the past year has shown that it can, indeed, happen here and now. We're not there yet, but we've come a lot closer, particularly in the area of what ordinary citizens will do to their neighbors.

American has no call to feel smug—or safe. We may not be as far down the road as Canada is, but it sure looks as if we are heading in the same direction. Should we panic? Despair? Absolutely not. But we'd darn well better be paying attention.

Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World by Cal Newport (Grand Central Publishing, 2016)

Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World by Cal Newport (Grand Central Publishing, 2016)

This is now the third Cal Newport book I've read. If you'd asked me, I'd have said it's the second, but while looking up the link for my review of Digital Minimalism, I noticed that 'way back in 2011 I had also reviewed How to Be a High School Superstar, which I had found to be incredibly important.

It's been a long time since I read How to be a High School Superstar, but if my memory is at all good, I think Deep Work may be the adult equivalent, with Digital Minimalism a natural consequence of those ideas.

Of the three books, Deep Work hits me more where I live at the moment. Not completely; as with Digital Minimalism, it is primarily about the business world, the world of outside-of-the-home careers. I'm certain Newport's ideas are just as important in our private lives; it's just a bit tricky to transfer them to the world of a busy young mother, say. Yet who better than a mother understands the importance (and difficulty) of finding time for concentrated thought?

Sadly, I'm going to disappoint some of my readers with the quotation section, but that just tells you how important I think the book is. Before I was two thirds of the way through Deep Work, I had more than 50 sticky notes marking places I wanted to quote. And more often than not it was several paragraphs rather than a nice, pithy couple of sentences. So basically, I gave up. I didn't mark nearly as many places in the last third of the book, because I knew I couldn't type them all out, and even if I could, my readers' eyes would glaze over early on.

As it turns out, you are going to get more quotations than I had originally thought (though they still don't begin to mine the value of Deep Work), because...

BREAKING NEWS!

Amazon is currently selling the Kindle version of Deep Work for $2.99!

I had already decided I wanted a copy of the book, but the Kindle version, and even the used paperbacks, were out of my price range. It's a popular book. I was struggling to finish reading the book in time—let alone write this review—because it is so popular at the library that I couldn't get it renewed. But while I was busy racking up fines, suddenly eReaderIQ (which I highly recommend) popped up with the news of Amazon's price drop "for a limited time."

I don't know how long that limited time will be, but $2.99 is good enough for me for almost any book that sounds interesting, and for this book it was a very timely godsend.

With the Kindle version I can copy and paste instead of laboriously typing out quotations. (I painstakingly converted all my sticky notes to Kindle highlights.) But the material simply does not lend itself to short quotes and easy summarizing. You really should read the whole book and allow it time to digest.

Here is Newport's definition of deep work:

Deep Work: Professional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit. These efforts create new value, improve your skill, and are hard to replicate. (p. 3).

I would argue that these activities hardly need to be "professional," but this is part of the career-world orientation of the book. I'm certain it's adaptable.

And here is his definition of shallow work:

Shallow Work: Noncognitively demanding, logistical-style tasks, often performed while distracted. These efforts tend to not create much new value in the world and are easy to replicate. (p. 6)

The ability (and time) to accomplish deep work has become critical in today's economy—at least if one doesn't want to make minimum wage (or less) in the hospitality industry. (Newport doesn't mention the hospitality industry; that's my observation having seen, both as one who lives in "Mickey's Backyard" and as a traveller.)

To remain valuable in our economy ... you must master the art of quickly learning complicated things. This task requires deep work. If you don’t cultivate this ability, you’re likely to fall behind as technology advances. (p. 13)

The growing necessity of deep work is new. In an industrial economy, there was a small skilled labor and professional class for which deep work was crucial, but most workers could do just fine without ever cultivating an ability to concentrate without distraction. ... But as we shift to an information economy, more and more of our population are knowledge workers, and deep work is becoming a key currency—even if most haven’t yet recognized this reality. (pp. 13-14).

However, deep work is disappearing at an alarming rate.

The ability to perform deep work is becoming increasingly rare at exactly the same time it is becoming increasingly valuable in our economy. As a consequence, the few who cultivate this skill, and then make it the core of their working life, will thrive. (p. 14).

This—and strategies for achieving deep work despite a society of ever-present distractions that actively fights against it—is what the book is all about.

As I mentioned above, mothers could tell Newport a thing or two about the difficulty of putting two coherent thoughts together when one's "office" is a household full of young children. What has changed in the business and academic worlds is that the demands of e-mail, virtual meetings, and other forms of rapid messaging and constant connectivity have brought the world of incessant interruption into the heretofore relatively quiet world of outside-the-home work. Add in Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and even the business-oriented social media sites like LinkedIn, and our opportunities for deep thinking have become virtually nil.

I was interested to note that the "working retreats" devised by our daughters (young, homeschooling mothers of large families, with cooperative husbands) to carve out time and space for deep work fit in perfectly with Newport's ideas. Not that they could go to the extremes of some of his examples:

[J. K.] Rowling’s decision to check into a luxurious hotel suite near Edinburgh Castle is an example of a curious but effective strategy in the world of deep work: the grand gesture. The concept is simple: By leveraging a radical change to your normal environment, coupled perhaps with a significant investment of effort or money, all dedicated toward supporting a deep work task, you increase the perceived importance of the task. This boost in importance reduces your mind’s instinct to procrastinate and delivers an injection of motivation and energy.

Writing a chapter of a Harry Potter novel, for example, is hard work and will require a lot of mental energy—regardless of where you do it. But when paying more than $1,000 a day to write the chapter in a suite of an old hotel down the street from a Hogwarts-style castle, mustering the energy to begin and sustain this work is easier than if you were instead in a distracting home office. (pp. 122-123)

Then there's this one:

An even more extreme example of a onetime grand gesture yielding results is a story involving Peter Shankman, an entrepreneur and social media pioneer. As a popular speaker, Shankman spends much of his time flying. He eventually realized that thirty thousand feet was an ideal environment for him to focus. As he explained in a blog post, “Locked in a seat with nothing in front of me, nothing to distract me, nothing to set off my ‘Ooh! Shiny!’ DNA, I have nothing to do but be at one with my thoughts.” It was sometime after this realization that Shankman signed a book contract that gave him only two weeks to finish the entire manuscript. Meeting this deadline would require incredible concentration. To achieve this state, Shankman did something unconventional. He booked a round-trip business-class ticket to Tokyo. He wrote during the whole flight to Japan, drank an espresso in the business class lounge once he arrived in Japan, then turned around and flew back, once again writing the whole way—arriving back in the States only thirty hours after he first left with a completed manuscript now in hand. “The trip cost $4,000 and was worth every penny,” he explained. (p. 125).

There is so, so much in this book, but I will only include two more quotations, both from footnotes:

The complex reality of the technologies that real companies leverage to get ahead emphasizes the absurdity of the now common idea that exposure to simplistic, consumer-facing products—especially in schools—somehow prepares people to succeed in a high-tech economy. Giving students iPads or allowing them to film homework assignments on YouTube prepares them for a high-tech economy about as much as playing with Hot Wheels would prepare them to thrive as auto mechanics. (Kindle p. 287, footnote to p. 30, emphasis mine)

The following footnote I include simply because it mentions The Art of Manliness, which keeps popping up in all sorts of surprising places, and holds a special place in my heart because it is a long-time client of Lime Daley, which feeds, clothes, houses, and educates a good number of our grandchildren.

The specific article by White from which I draw the steps presented here can be found online: Ron White, “How to Memorize a Deck of Cards with Superhuman Speed,” guest post, The Art of Manliness, June 1, 2012, http://www.artofmanliness.com/2012/06/01/how-to-memorize-a-deck-of-cards/. (Kindle p. 287, footnote to p. 177)

One thing I especially appreciate about this book is that Newport lays out the problem, and offers suggestions for combating it, but is not dogmatic about the solutions: he knows that once people (and companies) are aware of what is going on, they will be able to craft battle plans that work best in their individual situations.

I can tell the author is young, for he focusses on the contributions of the internet and social media to our splintered attention, and mostly gives earlier forms of distraction a pass. Neil Postman, Marie Winn, and others pointed out back in the 1970's and 80's the addictive nature of television, its deliberate shortening of our attention spans, and the changes it makes to the human brain. And although books and reading are generally indiscriminately lauded by those trying to battle the functional illiteracy of our times (does it matter that someone can read if he doesn't?), the design of much of today's reading material contributes its fair share to the diminution of our ability to concentrate. No doubt the internet, social media, and smart phones are the greatest problem, but it doesn't start or stop there.

As usual, I don't agree with everything Cal Newport says, but there's so much important here it's really worth your $2.99. If you miss the sale, it's certain to be in your public library, though probably with a waiting list.

I love our church. We have an awesome priest, a fantastic music director, a diverse congregation, and a choir of wonderful people who are managing to hang together as a choir despite having been unable to meet in person for over a year. Most amazing is that our form of worship feeds my heart and soul as none other has ever done. And the church is less than 10 minutes away from our house.

But—there's always a "but," right?—this past Sunday I had the best church experience I've had in months. We had to be in another part of town in the afternoon, so on the way we paid a visit to our previous church, one that has remained dear to our hearts even though circumstances had forced us to move on.

There I was reminded that when it comes to worship and music, I really am a high-church Anglican at heart. There are few churches in our area that have that form of worship service, and ours is a prime example, though greatly hampered by pandemic restrictions, especially those that minimize singing. The more low-church service we attended last Sunday made that clear to me. (And that wasn't even the church's "contemporary" service!) But—yes, another "but"—we were overwhelmed by the friendliness of the church, the welcome of old friends, the particular style of the music director (an unbelievably talented person and dear friend), the priest's pastoral heart, and the fact that here is a church that has managed to keep its people safe without unduly sacrificing the gathering-together and the physical touch that is so vital to that which makes us human. Unlike many churches, they have thrived during the pandemic, and it's not hard to guess why.

Hugs! They give hugs! (Though only to those who want them.)

I was unbelievably, quietly, happy all day. There were other reasons for that, but the church experience was a big part of it. It was a huge boost to my somewhat shaky mental health. I am a hard-core introvert who loves to be home, requires times of solitude to function, and has so many projects going on that boredom is very nearly not in my vocabulary. I have a husband who is very good at giving hugs! Plus, I'm not really a touchy-feely kind of person. It kind of creeps me out when people stand too close or touch me when conversing—and that was before COVID-19 entered the picture. If I am feeling significant distress because of the pandemic restrictions, what must it be like for others with greater needs, and for those who live alone?

I'm including here a video of the service. It is no mark of disrespect to our own church that I don't post our services, which are also livestreamed. I'd love to, but valiant as are the efforts of our people, we're not there yet in quality, especially for the audio.

Note to our children, who are the main reason the video is posted here: You will not have time to watch the whole service, but you will definitely want to check out the prelude (about 4:07-11:33) and the offertory (about 50:33-52:20). (The tambourine player in the offertory is, alas, not me.) If you can listen to this without tearing up, you'll be doing better than I did.

Permalink | Read 1253 times | Comments (2)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Porter received the following in an e-mail from George Friedman of Geopolitical Futures. At the end Friedman writes, "A referral is the best compliment. Feel free to forward this email to friends and colleagues," so I trust he will not mind if I quote substantially from it. You could read the entire article here, but it is behind a pay wall. As he often is, Friedman is spot-on. (Bolded emphasis mine.)

On Thursday, my wife and I got our second COVID-19 vaccination. ... The vaccine is incredibly successful, we’re told, which I would expect given the amount of money spent by my government in developing it. But my government is telling me that in spite of the vaccine nothing will change. I must maintain social distance, wear a face mask and so on. The vaccine’s creators say it’s unclear if the virus can still infect someone. ... [But] the continuous usage of masks can have unintended consequences.

It is often said that wearing a mask and maintaining distance is a trivial burden to pay for safety. But I take issue with that argument. ... Talking is far more complex than merely hearing words. Humans communicate much with facial expressions....

Humans use the face to identify threats; criminals wear masks as much to hide their intentions as they do to conceal their identities. Someone enraged at you or planning to harm you looks a certain way, someone delighted to see you another. It is not only the mouth that speaks to you. The muscles in the face can reveal tension or pleasure. The nose moves. The eyes reveal much. Facial expressions are much harder to interpret behind a mask. If you are very bored, ask your spouse to put on a mask and interpret their true feelings by the eyes alone. It can be done, but without context the probability of being wrong soars. The mouth, nose and lower half of the face are the checksums on what is said, and the mask impedes that greatly.

You can text or phone, but the ability to see those you speak to, or stand close to a stranger you just met, is indispensable to being human. So by definition, masks and distancing disrupt the process of being human. Ironically, if someone is speaking with a well-made mask, they are frequently incomprehensible unless you are a lot closer than six feet apart. The mask and social distancing tend to be mutually destructive.

Now, if these measures are the only ways to avoid mass death, then obviously they are necessary. But the assertion that these measures protect without cost is untrue. On multiple levels they impose costs that we may not yet understand. Learning how to play as a child, exploring the limits of tactile interaction, is essential to adulthood. My argument is not against these measures, if they are truly vital, but the cost-benefit must be addressed, and if the measures involve real costs, they should be imposed cautiously. Finding out if the vaccine makes me not infectious must be figured out quickly, as I fear the costs of a year of massive social and economic disruption are mounting. If the mask is essential to prevent another surge, so be it. But do not treat social distancing and masking as a trivial matter.

I worry most of all for the children. There are already many people, e.g. those on the autism spectrum and those we casually referred to as nerds in the days before everything had to have a diagnosis, who have difficulty reading social cues. Thanks to the pandemic restrictions, we now have a large cohort of children who have spent a critical formative year without broad access to facial cues, and with limited in-person social interaction. There is no way this will not have a detrimental affect on their socialization.

Long-time readers will know that I am not, absolutely not, worried that children are not going to school. For decades I have been convinced that education is essential but school is not; in fact, school is often out-and-out harmful. I laugh when people express concern that home-educated children are missing out on socialization, because their opportunities for social interactions with people of all ages and backgrounds are generally much richer than those of children who spend most of their time in school classrooms. But the "homeschooling" of children who normally go to school is a very different thing, and they do not likely have the rich networks those who homeschool have already developed. Plus, during the pandemic homeschools have also been shut off from their usual experiences. Whether public-, private-, or home-educated, a generation of children is being marked, and not for the better, by masks and anti-social distancing.

As if this weren't concern enough, apparently re-opening schools is also dangerous. There's this news from Quebec, Canada, where in at least three separate incidents the government has had to recall face masks that had been widely distributed, including to schools and day care centers, and were later feared to be causing lung damage.

It is one thing to wear a mask for short periods of time—though I wouldn't ever be thrilled at the prospect of inhaling toxic materials—but quite another for children—children!—to be endangering their lungs for hours on end, and months on end, while in school. We're so concerned, and rightly, about second-hand smoke in homes where children live, but for all we know this could be as bad or worse.

I've been told many times that we shouldn't fuss about wearing masks, because doctors and nurses and others wear masks professionally for long periods of time. Actually, I worry about them, too—but at least they are adults, whose lungs and social skills have long passed their most sensitive formative years. They are wearing them much more now than they used to—my eye doctor couldn't get his insurance renewed unless he had a policy of wearing a mask at all times in his office. In fact, I'm wondering if the habit of medical workers wearing masks, as important as it may be for reasons quite apart from COVID-19, might be playing a significant role in the depersonalization of medical care. I know, there are many factors involved. But when one's doctor or nurse looks more like a normal human being and less like a faceless alien, the medical care feels better. Especially, I daresay, to children.