In the Blood: A Jefferson Tayte Genealogical Mystery by Steve Robinson (Thomas & Mercer, 2014)

In the Blood: A Jefferson Tayte Genealogical Mystery by Steve Robinson (Thomas & Mercer, 2014)

This was another find from my book-loving, book-giving sister-in-law, who also shares my love of genealogy. I am now hooked, and was delighted/dismayed to discover five more books in the series waiting to suck up my reading time. I immediately ordered the next two from our library.

In the Blood is not profound reading, there's a small amount of bad language, and a little too much violence for my taste. By now you know I'm quite sensitive to such things, especially since I read nearly everything with an eye toward its appropriateness for sharing with grandchildren. But in this I find it only a minor problem, easily outweighed by the enjoyment I found in the story. Apparently a little character-appropriate bad language in a novel doesn't bother me nearly as much as the same words in a serious, non-fiction book.

Would I be so anxious to read the remaining books in the series if it weren't for the genealogical angle? It's hard to say; although you don't need to know anything about genealogy to appreciate the mystery, it certainly made it more enjoyable for me. And having recently completed a Great Courses series on Mystery and Suspense Fiction, I know that In the Blood is much more my style than most of what's out there.

How I Killed Pluto and Why It Had It Coming by Mike Brown (Spiegel & Grau, 2010)

How I Killed Pluto and Why It Had It Coming by Mike Brown (Spiegel & Grau, 2010)

This book by a scientist—a Caltech scientist no less—was such a joy to read I took time to look for a ghostwriter. But I soon came to the conclusion that Mike Brown is just a good writer with the usual editorial assistance.

How I Killed Pluto is primarily the story of the discoveries and controversies that led to the loss of Pluto as our ninth planet—with just enough anecdotes from his personal life to keep it grounded. Brown is not the first person to have his life upended by a baby who arrived a few days before schedule, but the dominos that fell from that distraction rang 'round the world. Not that Brown has any regrets about paying more attention to his daughter than to writing a paper about his astronomical research.

Having been, for a number of years, the go-to computer person in a research lab, I am not burdened by the illusion that scientists are saints dedicated to the pursuit of the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. They are human beings and just as prone to pride, greed, and falsification as the rest of us poor sinners. If you retain any such illusions, How I Killed Pluto is a good antidote—yet without bitterness.

Mostly, however, How I Killed Pluto is a good, layman's guide to the rigors and beauties of astronomy, and the best explanation I've heard yet as to why Pluto is no longer considered a planet. Pluto was not so much demoted as returned to its rightful place. As I read, I kept thinking of Rudyard Kipling's Jungle Book. Raised from infancy by Mother and Father Wolf, the child Mowgli considered himself to be a wolf, as did his wolf family. But as he grew, and as he discovered other beings with a much greater resemblance to himself, it became obvious to all that he was no longer the simple Mowgli of the Seeonee Wolf Pack. His heart was there, but he didn't really fit. (Please try to ignore the images in your mind of the Disney version of the story, and concentrate on what Kipling wrote.)

Similarly, as more and more objects were found that orbit our sun, inclucing Brown's own Eris (originally nicknamed Xena), the discovery that precipitated Pluto's fall, it became clear that Pluto, long considered to be the coldest, smallest, and most distant of our solar system's family of planets, is instead one of the largest of another whole species of celestial objects.

I can live with that.

Side note 1: I really miss the good old days of punctuation. No, I'm not—in this case—referring to the rampant abuse of the apostrophe, but to the days when profanity in publications, if it occurred at all, was modestly represented by a mostly random sequence of punctuation marks. I do not call it progress that authors of otherwise perfectly delightful books somehow think it better to be explicit in their swearing. Except for one word—one word!—How I Killed Pluto would be a perfect gift for our oldest grandchild. I understand that Brown wanted to describe in detail his girlfriend's stunned response to his proposal, but would it have killed him to have left it at, "You are such a &%$*#"?

Side note 2: Many of the books on our overflowing bookshelves came from my father's collection, which had been amassed through eight decades of reading. In his later years, his daughter-in-law was a prime contributor to his collection. Today, nothing proclaims my status as family matriarch more than that I am now the recipient of her bounty. She knew my father well, and she knows me also; her books are almost always fascinating. How I Killed Pluto is one of them.

As much as I enjoyed the book, I have only one quotation—and that has nothing to do with astronomy.

Diane and I often joke about parents who think that everything their children do is exceptional. Intellectually, we always understood that Lilah would likely be good at some things, not as good at other things. Exceptional is a pretty high bar. But reading ... books about early childhood and watching Lilah develop, I finally understood. She is exceptional, because early childhood development is about the most exceptional thing that takes place in the universe. Stars, planets, galaxies, quasars are all incredible and fascinating things, with behaviors and properties that we will be uncovering for years and years, but none of them is as thoroughly astounding as the development of thought, the development of language. Who would not believe that their child is exceptional? All children are, compared to the remainder of the silent universe around them.

Amen and amen!

Where did the month go?

This Ramadan I was going to join my Muslim friends for one day of their month-long fast. But suddenly the season is over—though I'm sure it did not feel sudden to those who were fasting.

This idea was not for spiritual reasons—I'm a Christian—but for awareness, and as a statement (to myself) of solidarity. To feel just a little bit of what it's like for our friends.

Having read stories from The Gambia in preparation for our visit there last year, I had been astonished at how difficult they find life during Ramadan fasting. After all, they get to eat a big meal before sunrise, and again after sundown. Skipping meals during the day is not fun, but hardly debilitating.

Then I remembered that few Gambians have the, um, caloric reserves that Americans do. I figured that must be the reason they find it hard to function well.

Well, that may be true—but then I discovered that there's more to Ramadan fasting than not eating.

There's not drinking.

I'm not talking about abstaining from alcohol, which observant Muslims do at all times. There's no drinking, period. No coffee, no tea, no soda, no water. Temperatures in the 90's and you can't drink. No wonder the soccer teams from the Christian tribes have a decided advantage during Ramadan.

In truth, I'm sure that's the reason I kept putting off my day of solidarity. I'm no stranger to fasting from food, but doing without water scares me. It probably would have been good to have had that tiny bit of identification with those whose lack of access to safe water makes this a year-round, not a day-long or even a month-long problem. But intimidation led to procrastination, and now the time is over. Maybe next year....

Anyway, my respect has gone 'way up for Muslims who keep Ramadan, fasting all day long for a month, year after year. Especially for those in hot climates, like the Gambia, where normal perspiration puts them at risk of serious dehydration. And for those living in the Far North in years when Ramadan occurs during the summer months. Could Mohammed have imagined that there would one day be Muslims living where the sun never sets?

It was not until I wrote this that I realized what a particular hardship Ramadan poses for Gambians: No ataya!

Permalink | Read 2089 times | Comments (0)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I opened up Facebook this morning to be greeted by the following "Suggested Post."

Some of my readers will immediately recognize the "Castle in Arquenay" as Château de la Motte Henry, where 10 years ago we celebrated Janet's birthday. We chose that fairy tale castle not because Janet is a romantic and highly imaginative person, although she is, but because the château happens to be the home of some dear friends, whose daughter would later be the flower girl in Janet's wedding. They are the most amazing hosts, and the experience was sublime.

The wonderful thing, as Facebook so cheerily told me, is that you, too, can have the Château de la Motte Henry experience! Well, not the friends-and-family perks, but let me tell you, these people know how to host an experience for their paying guests as well! Don't let the price tag put you off—share the cost with friends; it's a huge place! (No, I don't get a commission; I just love sharing something so special.)

If nothing else, take the time to go to the booking site, browse, and dream. Check out the amenities, marvel at the photos. I quote from the overview:

*JUST LISTED AS ONE OF "THE TIMES' TOP 20 CHATEAUX IN FRANCE" FOR HOLIDAY RENTALS!* -- (If you are a group larger than 14, please inquire about additional space & rates.) Live a fairytale dream in this romantic 19th century castle with its own private lake, swimming pool & cinema. Your senses will be dazzled with stunning views, gentle sounds of birds and rippling water, and the rich scents of roses and lavender. You will luxuriate in the privacy of 29 secluded acres, but only travel 2 km to reach all amenities. Whether you are a family, corporate group, or reunion of friends, the château offers pampering, fun and relaxation in a sublime setting for groups both large and small.

The château is an historically listed property, once open to the public, and now privately owned and operated. Featuring a motte (mound) from the time of Henry II surrounded by a moat, spectacular parkland, ancient trees, a private spring-fed fishing lake, and a Renaissance-inspired swimming pool within a secluded walled rose garden, the château is a haven of peace and tranquillity.

Here one can bask in the glorious French countryside, or discover the riches of the surrounding areas of the Loire Valley, Brittany & Normandy from this central location. Children & adults alike will delight in visits to the famous Loire châteaux, Mont St. Michel, D-Day Beaches, the fabulous Puy de Fou theme park and Zoo de la Fleche, all within a 1.5 hour drive. Within 15 minutes drive, one can experience beautiful gardens, golf, riding, nature-activity parks, river cruises, museums, stately homes & more. Or, you may simply never wish to leave the grounds of your very own château...

The château offers extremely spacious bedrooms, all with en-suite bathrooms; reception rooms comfortably yet elegantly renovated in keeping with the romantic style; & wonderful facilities for self-catering, such as a recently renovated designer kitchen with granite and marble-mosaic finishes, as well as three outdoor BBQs.

Special amenities include: Nespresso Machine, Bathrobes, Slippers, Large Welcome Basket, Champagne Reception on Arrival, Toiletry Kits in Bathrooms

Here's another view, Janet's own picture from a decade ago. Can you imagine walking through the woods and suddenly seeing this through a break in the trees?

Facebook is scarily good at surprising me with relevant ads, but this one was the most amazing yet.

Permalink | Read 2447 times | Comments (0)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Computing: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Travels: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Rising Strong: The Reckoning, the Rumble, the Revolution by Brené Brown (Spiegel & Grau, 2015)

Rising Strong: The Reckoning, the Rumble, the Revolution by Brené Brown (Spiegel & Grau, 2015)

Once more, our library is making sure I read Brené Brown's books in the wrong order; my hold for Rising Strong, her most recent book, came through before I Thought It Was Just Me, one of her earliest. It was okay, though, because I've read enough by now to be more able to handle her style. (See Daring Greatly and The Gifts of Imperfection.) As with the other books, her style gets in the way for me—I don't mean so much her writing itself, which is fine, as the way she chooses to express herself, e.g. redefining terms to mean something other than as they are commonly understood, too much "psychology-speak," too many references to pop culture (music and movies), and her habit of sprinkling her paragraphs with profanities (which I consider unprofessional as well as rude). That doesn't change the fact that she has some important insights, it just means I have to dig a little harder to understand them. One of the strengths of this book is the many examples and anecdotes that illustrate her ideas.

After inadequately summarizing Rising Strong as how we can learn to get up stronger and better after falling flat on our faces, I'll move right to the quotations. (Bold emphasis mine.)

Creativity embeds knowledge so that it can become practice. We move what we're learning from our heads to our hearts through our hands.

If there's one thing I've learned over the past decade, it's that fear and scarcity immediately trigger comparison, and even pain and hurt are not immune to being assessed and ranked. My husband died and that grief is worse than your grief over an empty nest. I'm not allowed to feel disappointed about being passed over for promotion when my friend just found out that his wife has cancer. You're feeling shame for forgetting your son's school play? Please—that's a first-world problem; there are people dying of starvation every minute. The opposite of scarcity is not abundance; the opposite of scarcity is simply enough. Empathy is not finite, and compassion is not a pizza with eight slices. When you practice empathy and compassion with someone there is not less of these qualities to go around. There's more. Love is the last thing we need to ration in this world. The refugee in Syria doesn't benefit more if you conserve your kindness only for her and withhold it from your neighbor who's going through a divorce.... Hurt is hurt, and every time we honor our own struggle and the struggles of others by responding with empathy and compassion, the healing that results affects all of us.

You can't skip day two. ... Day two, or whatever that middle space is for your own process, is when you're "in the dark"—the door has closed behind you. You're too far in to turn around and not close enough to the end to see the light. ... What I think sucks the most about day two is ... it's a non-negotiable part of the process. Experience and success don't give you easy passage through the middle space of struggle. They only grant you a little grace, a grace that whispers, "This is part of the process. Stay the course." Experience doesn't create even a single spark of light in the darkness of the middle space. It only instills in you a little bit of faith in your ability to navigate the dark. The middle is messy, but it's also where the magic happens.

We have to have some level of knowledge or awareness before we can get curious. We aren't curious about something we are unaware of or know nothing about. ... Simply encouraging people to ask questions doesn't go very far toward stimulating curiosity. ... The good news is that a growing number of researchers believe that curiosity and knowledge-building grow together—the more we know, the more we want to know.

That's what I've been saying for years about early childhood education; education in general, in fact. Which is why I've never been sympathetic to those who insist that young children should not learn "dry facts." For young children, facts are anything but dry—unless we make them so.

[Explaining her insight as to why she and her husband each found it easier to handle life with their children when the other was out of town.] When I'm on my own for a weekend with the kids, I clear the expectations deck. When Steve and I are both home, we set all kinds of wild expectations about getting stuff done. What we never do is make those expectations explicit. We just tend to blame each other for our disappointment when they're not realized.

We accept our dependence as babies, and ultimately, with varying levels of resistance, we accept help as we get to the end of our lives. But in the middle of our lives, we mistakenly fall prey to the myth that successful people are those who help rather than need, and broken people need rather than help.

It doesn't nullify her point, but babies don't happily accept dependence. They're fighting tooth and nail to "do it self" long before they can utter those words. They can't help being born dependent, but the will to be dependent is learned. Lounged in a chair in front of the television or a video game: "Mom, I'm hungry!" "Bring me a beer, honey!"

Most of us were too young and having too much fun to notice when we crossed the fine line into "behavior not becoming of a lady"—actions that call for a painful penalty. Now, as a woman and a mother of both a daughter and a son, I can tell you exactly when it happens. It happens on the day girls start spitting farther, shooting better, and completing more passes than the boys. When that day comes, we start to get the message—in subtle and not-so-subtle ways—that it's best that we start focusing on staying thin, minding our manners, and not being so smart or speaking out so much in class that we call attention to our intellect. This is a pivotal day for boys, too. ... Emotional stoicism and self-control are rewarded, and displays of emotion are punished. Vulnerability is now weakness. Anger becomes an acceptable substitute for fear, which is forbidden.

Fault-finding fools us into believing that someone is always to blame, hence, controlling the outcome is possible. But blame is as corrosive as it is unproductive.

Breaking down the attributes of trust into specific behaviors allows us to more clearly identify and address breaches of trust. I love the BRAVING checklist because it reminds me that trusting myself or other people is a vulnerable and courageous process. [I've shortened the explanations a little.]

- Boundaries—You respect my boundaries and when you're not clear about what's okay and not okay, you ask.

- Reliability—You do what you say you'll do.

- Accountability—You own your mistakes, apologize, and make amends.

- Vault—You don't share information or experiences that are not yours to share.

- Integrity—You choose courage over comfort. You choose what is right over what is fun, fast, or easy. And you choose to practice your values rather than simply professing them.

- Nonjudgement—I can ask for what I need, and you can ask for what you need. We can talk about how we feel without judgment.

- Generosity—You extend the most generous interpretation possible to the intentions, words, and actions of others.

"No regrets" doesn't mean living with courage, it means living without reflection. To live without regret is to believe you have nothing to learn, no amends to make, and no opportunity to be braver with your life.

People learn how to treat us based on how they see us treating ourselves. ... If you don't put value on your work, no one is going to do that for you.

Designed to Move: The Science-Backed Program to Fight Sitting Disease & Enjoy Lifelong Health by Joan Vernikos (Quill Driver Books, 2016)

Designed to Move: The Science-Backed Program to Fight Sitting Disease & Enjoy Lifelong Health by Joan Vernikos (Quill Driver Books, 2016)

You've heard it before: Sitting is the new smoking. Dr. Vernikos makes a convincing case for the rapid deterioration of both the body and the brain during as little as 30 minutes of sitting. As a health researcher with NASA, she observed that the bodies of astronauts "aged" ten times as fast in weightless conditions as at home on the earth. Then she observed the same results in people who sit for much of the day, i.e. all of us.

There are plenty of studies to back her up. The results are not always precise, because most of the data is from statistical analysis of studies that were not originally intended to be about sitting. But the pattern is clear enough, nonetheless.

I'll spare you the details; the writing is not the best, and tends to be repetitious. In a nutshell, however:

- Gravity is our friend, no matter what you may think when you trip and fall flat on your face. Most of our bodily systems depend, one way or another, on motion in the presence of gravity to function correctly.

- When we sit, we deprive our bodies of most of the beneficial effects of gravity.

- Exercise is good, but it is not the answer to the problem of sitting. An hour of intense exercise at the gym does not counteract hours spent seated in front of a computer or watching television.

- But there's really good news: what does counteract the problem of sitting is as simple as taking a break every 30 minutes to stand up, and sit down again. That's it. Of course, more movement is better. Frequency and variety are much more important than intensity. That said, if all you do is break up your sitting by standing briefly every half hour, you're doing your body and brain enormous good, even down to the biochemical level. If you're at the computer, you may want to set a timer—we all know how fast two hours can go without our knowledge. If you are watching commercial television, stand up during the commercials. Done.

If there is a word that defines the solution to our sitting woes, it is alternating—from sitting to standing, from standing to bending over to pick something off the floor, from squatting to jumping up, from stretching up to bending sideways, moving up every which way, kneeling down in prayer to touch your forehead on the ground and back upright again. Add frequent and variety to alternating and you have the keys to the solution.

From this persepctive, it's clearly healthier to be a sit-kneel-stand Episcopalian or a jump-dance-wave-your-arms Pentacostal than a sit-in-the-pew-for-an-hour Presbyterian. :)

And best of all to be a little child.

"She's a professional tambourine player," the choir director explained as he handed me that instrument to accompany our Palm Sunday music.

He was joking, of course, but I was serious in my response, "Actually, I'm a professional cymbal player."

If, that is, you call professional someone who gets paid for his work, and consider a free hamburger and can of soda to be qualifying compensation.

In church, we are known as mild-mannered, respectible singers: Porter is the tenor who leads the Psalm on most Sundays and is the choir's go-to guy for handyman jobs. I'm the alto with the over-ready tongue who tries to make sure that when the choir's not singing, we're laughing.

But there's another side to our musical lives, and it came to my attention recently that many of our fellow choir members have no idea what we morph into every July 4th. As requested, I'm now Revealing All.

It began back in 1993, when our then 13-year-old, trumpet-playing daughter read a column by Bob Morris in the Orlando Sentinel about an organization known as the World's Worst Marching Band, the official band of the (in)famous Queen Kumquat Sashay. When she proclaimed, "I want to join THAT," Porter immediately arranged to take her to one of their rehearsals to check it out. We were homeschoolers at the time, and eveyone knows that homeschoolers are weird and unsocialized and never go out.

Not really, but this truly was some of the weirdest and most wonderful socialization ever. The whole family became involved—and that IS typical of homeschoolers—despite the fact that our first impression of Maestro Tony "Stinky" Peugh was of him conducting the band with a cigarette protruding from each ear. You can read more about the band in this Sentinel article from 1993. Despite the name, most of the members were excellent, professional musicians—but they didn't discriminate against the rest of us.

It was so much fun. Not only did we march in the Sashay and many other local parades, but we also took road trips for Independence Day parades in Atlanta and Philadelphia. We played concerts for the newly-formed Fringe Festival, the Maitland Art Festival, at the Citrus Bowl, at several Disney events, even (in an absolute deluge) for the Santa Salutes the Soaps Parade—venues so eclectic I can't count or even remember them all now.

But as with so many good things, the World's Worst Marching Band eventually ran its course. Later, the intrepid Chaz Waldrip resurrected it, in the form of the ACME All-American Alumni Marching Band, which attempted to be a little more serious. It was still fun, but didn't last long. Finally, Richard Simonton, a band member from Geneva (Florida, not Switzerland), found a scheme that worked to keep us going. Richard is quiet, self-effacing, and brilliant. He's done a lot of good, real work in his time—don't look him up in Wikipedia, though; you'll get his much more famous father—but as far as we're concerned, the Greater Geneva Grande Award Marching Band is his magnum opus.

The GGGAMB operates on a much more modest scale than the WWMB: We have ONE gig per year. On the morning of July the 4th, we meet for a short rehearsal, after which we march in Geneva's short Independence Day parade and then perform for their wonderful, small-town celebration. In 2015 I wrote a post about some of the joys of that once-a-year performance.

For those who would prefer a shorter version, I've edited a video taken of that year's concert by Rick Hughes of the Community Church of God. In it you can see the band in action, with my award-winning cymbal performance. Award-winning? Hang in there till the end and you'll see what I mean.

The video also shows Porter in his even more important role as Gunga Dad, the man who keeps the band well hydrated. This is more of an act than a necessity in these days of ubiquitous water bottles, but in 1993, with the July sun melting the asphalt on Atlanta's Peachtree Street parade route, his tireless work gave us the distinction of being the only band in the parade not to have someone faint.

So there you have it. Our Secret Lives Revealed. Auditions are now open for this year's Independence Parade. That's "auditions" as in "let me know you're interested, and I'll slip your name to the right people.

Dorothy L. Sayers: A Careless Rage for Life by David Coomes (Lion Publishing, 1992)

Dorothy L. Sayers: A Careless Rage for Life by David Coomes (Lion Publishing, 1992)

I'm a long-time fan of the works of Dorothy Sayers, though I'm somewhat embarrassed to admit that my reading has been almost—though not quite—exclusively of her detective fiction. That's a fault I'm working to correct, though sadly our library isn't of much help.

Coomes' book is a wonderful examination of the person behind the great mind and brilliant writer. I'd say it is a fair biography, doing Sayers justice, giving her due credit for her amazing accomplishments without whitewashing her character flaws or excusing her sins—of which she was very much aware.

Despite my respect for the author's work, I can't say the same for his proofreaders and editors. I know how easy it is to have read a manuscript so many times that you simply can't see the errors anymore, but I still wonder how everyone could have missed the amusing error that appears on every page of Chapter 6, in the title, 'The deadlines of principles.' Having read Gaudy Night multiple times, and recently, I knew immediately that the title was a quote from that book, and that it was wrong. Even in the body of the chapter, where the passage in which the phrase appears is quoted in longer form, it is misquoted. The relevant sentence is, The young were always theoretical; only the middle-aged could realize the deadliness of principles. Not deadlines. Deadliness. Until now I had never noted the one-letter difference that changes the meaning so dramatically.

The mistake is repeated at least 16 times. That spell check failed to catch the error is understandable, since both are valid English words; that it slipped by all the humans is less so. But maybe they hadn't read Gaudy Night, where the deadliness of principles is not just a passing phrase, but central to the mystery, and to the book.

Much of the author's insight into the character of Sayers comes from her writings, especially her letters, and he quotes liberally. That is how it came to be that all the quotations below are Sayers' own words rather than Coomes'. As always the bold emphasis is mine.

I was [as a child] always readily able to distinguish between fact and fiction, and to thrill pleasantly with a purely literary horror...I dramatised myself, and have at all periods of my life continued to dramatise myself, into a great number of egotistical impersonations of a very common type, making myself the heroine (or more often the hero) of countless dramatic situations—but at all times with a perfect realisation that I was the creator, not the subject, of these fantasies.

"More often the hero"—that was true for me, as well. I believe it is the natural consequence of the sad fact that until recently nearly all the interesting roles in literature were taken by men.

For some reason, nearly all school murder stories are good ones—probably because it is so easy to believe that murder could be committed in such a place. I do not mean this statement to be funny or sarcastic; nobody who has not taught in a school can possibly realize the state of nervous tension and mutual irritation that can grow up among the members of the staff at the end of a trying term, or the utter spiritual misery that a bad head can inflict upon his or her subordinates.

I'm sure my teacher friends would agree.

I am still obstinately set upon [a certain producer for the play]. Very likely it is impossible. I do not care if it is. If the cursing of the barren fig-tree means anything, it means that one must do the impossible or perish, so it is useless to tell me it is not the time of figs.

I will not cease from mental fight nor shall my sword sleep in my hand till I have detected and avenged all mayhems and murders done upon the English language against the peace of our Sovereign Lord the King, his Crown, and dignity.

A woman after my own heart.

[On the popularity of detective novels] Life is often a hopeless muddle, to the meaning of which [people] can find no clue; and it is a great relief to get away from it for a time into a world where they can exercise their wits over a neat problem, in the assurance that there is only one answer, and that answer a satisfying one.

Artists who paint pictures of our Lord in the likeness of a dismal-looking, die-away person, with his hair parted in the middle, ought to be excommunicated for blasphemy. And so many good Christians behave as if a sense of humour were incompatible with religion; they are too easily shocked about the wrong things. When my play was acted at Canterbury, one old gentleman was terribly indignant at the notion that the builders of that beautiful Cathedral could have been otherwise than men of blameless lives.

Certainly that attitude is a problem even today, but the indignant gentleman may or may not have been real. Sayers—who had worked in an advertising agency—and her publishers knew very well the publicity value of controversy, and were not above fueling the flames with fake letters of complaint. Truly, plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose.

To achieve a great and godly work one should always employ a good architect who lives an immoral life rather than a poor architect who lives a blameless life.

The real question is, why aren't there more good architects who live blameless lives?

I do not feel that the present generation of English people needs to be warned against the passionate pursuit of knowledge for its own sake: that is not our besetting sin. Looking with the eye of today upon that legendary figure of a man who bartered away his soul [Faust], I see in him the type of the impulsive reformer, over-sensitive to suffering, impatient of the facts, eager to set the world right by a sudden overthrow, in his own strength and regardless of the ineluctable nature of things.

Every great man has a woman behind him ... And every great woman has some man or other in front of her, tripping her up.

It's not enough to rouse up the Government to do this and that. You must rouse the people. You must make them understand that their salvation is in themselves and in each separate man and woman among them. If it's only a local committee or amateur theatricals or the avoiding being run over in the black-out, the important thing is each man's personal responsibility. They must not look to the State for guidance—they must learn to guide the State.

[What the press clearly shows] is an all-pervading carelessness about veracity, penetrating every column, creeping into the most trifling item of news, smudging and blurring the boundary lines between fact and fancy, creating a general atmosphere of cynicism and mistrust. He that is unfaithful in little is unfaithful also in much; if a common court case cannot be correctly reported, how are we to believe the reports of world-events?

Once again, plus ça change....

To read only one work of Charles Williams is to find oneself in the presence of a riddle—a riddle fascinating by its romantic colour, its strangeness, its hints of a rich and intricate unknown world just outside the barriers of consciousness; but to read all is to become a free citizen of that world and to find in it a penetrating and illuminating interpretation of the world we know.

Ah, so that's my problem. I read Williams' The Place of the Lion, but found myself in a state of utter confusion. I need to read more.

What we say we want to abolish is the artificial inequality of goods & social status; but I am not sure that this is being accompanied as it should be any recognition of a real hierarchy of merit. I seem to detect a general disposition to debunk the natural hierarchies of intellect, virtue & so forth, & substitute, as far as possible, an all-round mediocrity.

It is arguable that all very great works should be strictly protected from young persons; they should at any rate be spared the indignity of having their teeth and claws blunted for the satisfaction of examiners. It is the first shock that matters. Once that has been experienced, no amount of late familiarity will breed contempt; but to become familiar with a thing before one is able to experience it only too often means that one can never experience it at all. This much is certain; it is not age that hardens arteries of the mind; one can experience the same exaltation of first love at fifty as at fifteen—only it will take a greater work to excite it. There is, in fact, an optimum age for encountering every work of art; did we but know, in each man's case, what it was, we might plan our educational schemes accordingly. Since our way of life makes this impossible, we can only pray to be saved from murdering delight before it is born.

Since I know that Sayers thought highly of the capabilities of children, and that she herself began to learn Latin when she was six years old, I don't think she's arguing against early education. But her point, here, would no doubt be understood by J. R. R. Tolkien, who stated that his book, The Hobbit, should not be read by anyone under thirteen. I don't agree, but he's the author. I think that Sayers, at any rate, is more opposed to the inoculation against great works that can come when they are dumbed down. Elsewhere she wrote, when told that the play she had written for children would go right over their heads,

I don't think you need trouble yourselves too much about certain passages being "over the heads of the audience." They will be over the heads of the adults, and the adults will write and complain. Pay no attention. You are supposed to be playing to children—the only audience perhaps in the country whose minds are still open and sensitive to the spell of poetic speech ... The thing they react to and remember is not logical argument, but mystery and the queer drama of melodious words ... I know how you would react to those passages. It is my business to know. But it is also my business to know how my real audience will react, and yours to trust me to know it.

This morning I found a good illustration for why it is important to look at the whole picture when trying to determine "what the Bible says."

As choir members, we've all cringed when a conductor addresses "singers and musicians," but did you know that it has Biblical imprimatur?

Your procession is seen, O God,

the procession of my God, my King, into the sanctuary—

the singers in front, the musicians last....— Psalm 68:24-25, English Standard Version

The King James Version is kinder, saying, "The singers went before, the players on instruments followed after."

Permalink | Read 1807 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Our church prides itself on its reputation as the most liberal church in our diocese.

That our diocese itself is somewhat of a traditional haven in an Episcopal Church that, frankly, has gone off the rails, is a major reason why we have not been driven to another denomination. The dismal state of the American Episcopal Church is not just my opinion, but that of most of the world's Anglicans. However, contrary to what happens in many denominations, the very structure of its services keeps it from going too far 'round the bend in any direction, and enables people of great diversity to worship freely together. I would hate to lose that.

Why, one might ask, do we not seek out a parish that is more in line with the diocese and less with the national leadership? After all, a church that was our home for many years, and which we still hold dear, is just that. It would be disingenuous not to mention that it is 45 minutes away, and our current church less than 10. But there's another, more important reason for being where we are:

We don't fit in.

I don't mean we feel unwelcome. Ours is a friendly church, and almost unmatched in the way children are respected in the service. A nicer bunch of people than our choir you'll not find anywhere. We share a lot in common. But there's no doubt that when it comes to many political, social, and theological issues, we are among a small minority.

One of the greatest dangers facing America today is that we don't know each other. We hang around, in both our real and our virtual lives, largely with people like ourselves. A community of empathetic people is important, even essential. That's the success of 12-step programs and other support groups formed around a particular need. We all need the encouragement of people who have been where we are and are going where we are going. We need a place to be at home, to be ourselves, to be fully accepted, to share inside jokes and to let down our defenses.

But too much of that can also lead to insularity and inbreeding. While we're not likely to forget that there are people who disagree with us, we're all too likely to forget that they are no less human than we are. You think that's crazy? Look at America today. We have become a nation of divisions that each think the others subhuman.

Is there a remedy? The best I can think of is to get out of our comfortable circles and work together with "the other" on something constructive. To find opportunities to meet together on common ground, to see each other as people with jobs and families, with trials and victories, as people who bring us meals when we are sick, and to whom we take meals in their need. People with whom we can learn that discussion is not war, difference is not division, and disagreement is not hatred.

Church, where we already have much common ground, and choir, where we have common work, are obvious places for us to find this interaction, at least at this stage of our lives. Is it frustrating at times, and lonely? Yes. But I've been there before, many times.

Who am I kidding? I've been there all my life. I've never fit in. I grew up a nerd, was the only girl in some of my classes and activities, always preferred classical to rock music, was considered an anomaly by my peers for refusing to lie to my parents, was a feminist until it became popular and then jumped ship, and developed decidedly unconventional attitudes towards birth, childrearing, and education—even in homeschooling I was philosophically an outsider among outsiders. So I'm accustomed to it.

And if I'm not going to fit in, our church is a great bunch of people not to fit in with.

Wait, that didn't come out at all the way I meant it.

They're a great bunch of people, and they don't mind if I don't fit in.

For now, this is where we should be. Will it always be so? Only God knows. As long as we are only swimming upstream and aren't fish out of water, I'm okay with that.

And hopeful for America.

Permalink | Read 2266 times | Comments (3)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

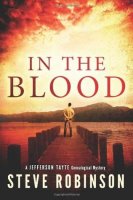

As part of my 95 by 65 program, I set the goal of walking the equivalent of from here to the home of our grandchildren in New Hampshire. This I completed in December of last year. At that point, I was so much in the habit of keeping track of my steps that I naturally chose a related goal for the continuation: walking to the home of our other grandchildren. This was a lot longer, and a little trickier, since they live in Switzerland. But since I was using the "crow flies" distance for my calculations anyway, I freely ignored the problem of walking on water across the Atlantic.

It has been a long trek, but I'm nearly there. Just 205 miles remain. Apparently I'm enjoying a long stroll through the Parc naturel régional de la Forêt d'Orient in France's Champagne-Ardenne region.

Will I arrive in time to celebrate my birthday? It will take some concentrated work, but that's my goal!

The Scene: A restaurant, where the "background music" is very much not in the background, and questionably musical.

She: Even if I knew enough to appreciate the music, even if I could understand the words and not be appalled by them, I still couldn't stand the driving drum beat. I just don't get the attraction of all that relentless pounding.

He: It's sexual.

She: You're kidding.

He: That's what they say.

She: Well, they must be right, because it gives me a headache.

Permalink | Read 1758 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The Royal Road to Romance by Richard Halliburton (Garden City Publishing, 1925)

The Royal Road to Romance by Richard Halliburton (Garden City Publishing, 1925)

Richard Halliburton was the Rick Steves of the early 20th century—with a few minor differences, such as not travelling with a camera crew, constantly putting himself into physical danger, and showing a marked disdain for societal conventions such as paying train fares.

Halliburton graduated from Princeton in 1921, the year my father was born. Scorning a more conventional life, he and a friend signed on to a ship, as ordinary seamen, and worked their way to Europe. The Royal Road to Romance is an enjoyable narrative of Halliburton's adventures, with and without companions, tramping all over Europe; slogging through the jungles of Southeast Asia; venturing into forbidden Afghanistan; climbing Mt. Fuji, solo, in the dead of winter; supporting himself by great thrift, petty theft, and articles occasionally mailed home to magazines eager to appease the American appetite for travel stories.

This is travel, and this is adventure, but it's also chock-full of history and geography, made all the more interesting because it was written when the world's geography and politics were vastly different from today's. Imagine, too, a world in which Halliburton managed to pay homage to many of his favorite sites, now tourist meccas, from the fortifications on Gibraltar to the Taj Mahal to Angkor Wat to the Great Pyramid of Cheops—up close and personal, for hours, entirely in solitude.

The Royal Road to Romance came to my bookshelves from my father's library, along with two other Halliburton books, The Glorious Adventure and New Worlds to Conquer. I'm looking forward to more of his well-written and fascinating stories.

Halliburton's life is not one to be emulated—he died at 39 attempting to cross the Pacific in a Chinese junk—and his stories have a light-hearted amorality about them that can be a little disconcerting, as can the racial attitudes and language of the time. But understood in context, I think this would be a good book for older grandchildren—as long as they don't develop a taste for schwarzfahren.

The least commonplace of the routes [from Peking to Japan], in fact, the forbidden, abandoned route for tourists, was through northern Manchuria to Harbin, thence to Vladivostok by the Trans-Siberian and across the Japanese Sea. With my tiger's tooth no longer protecting me, with an arctic winter at hand, with a Chinese bandit army in control of one-half the railroad and the officious Bolsheviks the other, only a determined seeker after novelty would have cared to travel this route. Its disadvantages were so numerous, the possibility of being delayed and harassed so great, my enthusiasm was only half-hearted when I began to make practical investigation. However, when the American and Bolshevik authorities refused point-blank to give me a passport, my ardor for Siberia—heretofore a very negligible quantity—burst forth in a holy flame, and with a determination fired by hatred of this injustice I vowed that now I would go, and defied all the officials in Asia to stop me.

Jim Bridger: Mountain Man by Stanley Vestal (University of Nebraska Press, 1970; originally published 1946)

I read this book, not only because of my 95 by 65 project's goal of reading 26 existing, unread books from my bookshelves, but because I remembered Jim Bridger from Porter's stories of his 1973 vagabond trip across the United States. He was particularly interested in Yellowstone National Park, which Bridger was one of the first white men to explore, and "Jim Bridger stories" were an enjoyable part of his research.

Consequently, I read this book with an eye towards its possible use as an introduction for our homeschooled grandchildren to the history and geography of that part of the country. Although the book is more serious and adult than I was expecting, it still might serve that purpose. It certainly was enjoyable for me to read.

On the other hand, I'm having trouble figuring out what age group the author intended as his audience. The text switches, often with apparent randomness, between straight narration and narration in what I assume to be mid-19th century Mountain Man vernacular. After a while, I became accustomed to the language, but to me this attempt to add color to the story only made it feel as if it were intended for a young audience. On the other hand, the "adult" situations and language don't commend the book to children. While certainly not graphic by today's standards, one must wade through several "hells" and one "nigger" plus some unpleasant descriptions of carousing—and of atrocities. And if the term "Indians" offends you when used in referring to Native Americans, you will cringe every time at the Mountain Man talk, in which they are always "Injuns," more often than not "cussed Injuns."

On the other hand, that was the way of the Wild, Wild West, and you're not going to get a truthful history of the time and place without some of it. And truth is what impresses me most about this book. Written in 1946, the tales are blessedly free of the modern myth that Native Americans were innocent and righteous until the white men came and ruined everything. On the other hand, it is more than usually honest for the time about the stupidity and cruelty of the whites. In addition to being a well-researched biography of Jim Bridger, discerning the man in the mythos that grew up around him, the book appears to be a fair depiction of the complex clash of Indian, explorer, pioneer, and military cultures.

I think Jim Bridger: Mountain Man would be an excellent addition to any homeschool study of American history—but parents should read it first.

The Oregon Trail following up the Platte through the buffalo country had frightened the game away. And, when a hundred thousand forty-niners came swarming over that trail, heading for California goldfields, the Indians became thoroughly alarmed, suspicious, and resentful. Buffalo would not cross that broad beaten "medicine road" which cut the Plains in two. After 1850 there were two herds instead of one: the Buffalo North and the Buffalo South. The coming of the white man had turned that great pasture along the Platte into a barren desert.

Neither the passing white man nor the starving Indian saw anything to admire in the other. The whites passed through too quickly to discover how false their notion of the Plains Indian was—the notion which they had brought from the Dark and Bloody Ground, the notion that every Indian was a treacherous thief and murderer, thirsting for the blood of every stranger and delighting in torture of the helpless.

The Indian hunter, on the other hand, whose most necessary virtues were courage, generosity, and fortitude, could only despise the caution, thrift, and sharp practice of the Yankees as the meanest vices; each being in his eyes simply a species of cowardice.

Because of this dislike and misunderstanding on both sides, there was constant friction and increasing distrust. But the Plains Indian had no newspapers to state his case, and so, by 1851, had been given a thoroughly bad name in the States.

There was constant enmity between Jim Bridger and the Mormon settlers, particularly their leader, Brigham Young. This excerpt also shows the integration of plain text and Mountain Man vernacular.

Some would have it that all the trouble between these two men originated in a woman's spite. These persons would have it that, after Bridger's Ute wife died in childbirth, July 4, 1849, Jim married a Mormon woman, that they fell out and parted, and that her spiteful, whispering tongue was the source of all the evil rumors about Bridger current among the Saints.

This story hardly fits Bridger's known circumstances, tastes, and habits. He had as much sense as any Mountain Man alive—and hardly any Mountain Man alive was fool enough to wed a fofurraw white gal from the settlements. Pale as a ghost, thin as a rail, and green as grass, a white gal was no good in camp or on the trail. Moreover, Mountain Men had lived so long among the pesky redskins that their idea of female beauty war an Injun idee, and you can lay to that. Bridger sincerely respected his Injun women, treated them as wives, and adored his halfbreed children. And in those days, even if he had wanted to wed a white gal—would she have had him?