I know the details of the following tale intimately and personally. But it is Everyman's Story.

There once was a man who worked tirelessly at his job for many years, and was widely praised for his accomplishments. However, his employers became dissatisfied with him, and began undercutting his authority and making his job miserable. When this was not sufficient to drive him away, they forced him out.

This is not actually an unusual story; It's frequently played out in corporate boardrooms, research laboratories, schools, churches, and non-profit organizations. What made this one a bit different is that the man was strong enough to refuse to attend his own farewell party. He was intended to be sent away with extravagant accolades, heaped with praises for the excellence of his work and service, and tearful farewells, but he would have none of it. It would have been insincere, hypocritical, and unbearable.

Much like the accolades heaped on President Biden once he decided to withdraw his candidacy for the upcoming presidential race. If it was his decision, which I highly doubt.

I may disagree with much that Joe Biden has done and wants to do. I would go so far as to label many of his actions evil, even traitorous, though I will grant him the courtesy of assuming his intentions were good.

But he doesn't deserve what has been done to him over the last four years, and especially recently. If you're going to abuse an elderly man, and then stab him in the back, for goodness' sake don't pretend to be doing it out of love.

As I explained before, I know I'm late to this party. But people are not done talking—so I've been jumping in.

No one seems to have the proper level of respect for 20-year-olds. I keep hearing the Butler shooter referred to as "a kid." Others are asking, "How could a 20-year-old manufacture the explosive devices supposedly found in his car without blowing himself up?"

At the risk of sending the FBI to his door, my 20-year-old grandson could easily and safely have made explosives. As far as I know, his gun experience may be limited to a few target shots at camp, but it would take him very little training and practice to get to the point where he could have made that shot. He wouldn't do anything of the sort, but he could have.

Has everyone forgotten that we routinely send 18-year-olds to fight in wars? That Admiral David Farragut commanded a prize ship in the War of 1812 when he was 12 years old? In the past, both men and women were routinely competent to do "adult" tasks at much younger ages than the majority of Americans teens are now. It is nothing but ageism to underestimate the abilities of a 20-year-old—or a 12-year-old, for that matter.

In all my decades of life I may have met more members of the United States Congress, but I only remember four.

I met Daniel Webster at a meeting of a group of homeschooling families that we were considering joining. He was at the time a member of the Florida legislature, and had worked tirelessly for educational freedom; it was a pleasure and a privilege to meet and talk with him.

I met Bill McCollum when our kids were in high school, through the Band Parents' Association and the most efficient and excellent work of his wife. They are still on our Christmas card list.

Next up was John Mica, who at the time was our own representative. That was at an event for members of the Morse Museum. He wasn't speaking, just attending, but he did make the rounds greeting people, including us.

I voted for our next congressional representative, Stephanie Murphy (one of the last Democrats to receive my enthusiastic support), but never did run into her.

She was followed by our current congressman, Cory Mills, whom I met while our respective units were waiting to step off in the Geneva, Florida Independence Day parade.

After that long introduction, the purpose of this post is to highlight Cory Mills in this CNN interview, where he brings his experience as a former Army sniper to his analysis of the security situation at the near-assassination of President Trump. I'm not sure which one of them I'm more impressed with: Mills, with his clear explanations and his call to turn down the heat in our rhetoric, or the interviewer, who listened and let him speak, a skill I've found to be rare among interviewers, including this one at other times. The interview was aired 10 days ago, but is no less valuable today. It's worth listening to the whole thing (11 minutes), including the brief Q&A afterwards.

If there ever was a time in my life when I enjoyed Whirl 'n' Puke rides at amusement parks, it was too far back in time for me to remember. Living in Central Florida, we spent more than our share of time at Disney parks, and could not wait for the kids to be old enough to ride the Mad Hatter's Tea Cups on their own.

I'm getting the same feeling about my former political party.

You may recall that I broke my lifelong association with the Democratic Party earlier this year, the final straw being when they disenfranchised me by cancelling Florida's presidential primary election.

Turns out, I was just ahead of the game. If I'd stayed a Democrat, they would have disenfranchised me more spectacularly, along with everyone else. Not that there isn't precedent—there's a long history of political slates being decided in smoke-filled rooms. (I do wonder what they're actually smoking these days.)

Here is the far-from-amusing, no-end-in-sight amusement park ride I feel stuck on:

- President Biden's cognitive decline has been obvious to much of the country at least since 2020. Even to me, and I tend to give public speakers a lot of leeway, because my own brain, which functions quite well when operating my fingers on a keyboard, seems to lose all sense of direction when it tries to operate through my mouth.

- I am also not surprised that there are many ordinary citizens who did not notice this decline, because, frankly, most people are just too busy to pay attention to anything more detailed than carefully edited sound bites, if that.

- But those closest to the president? The vice president, cabinet members, secret service agents, the press corps, his doctors, his own family? How could they not have seen it?

- And yet for years, right up until his performance in the presidential debate (which was called "disastrous" but should have been no surprise at all), they assured us, in a united front, that the president was very healthy, sharp as a tack, and more than fully competent. Was it mass delusion, willful blindness, or simply lying?

- "Do not call conspiracy what these people call conspiracy"—but if all these people have been lying, what else would you call it?

- But if they were lying, and not deluded, why didn't they stop Biden from agreeing to the debate in the first place? How could they possibly have been surprised by what occurred?

- Even after the debate, many of them still maintained that it was just "one bad night," until the tide of opinion turned against them. What were they thinking?

- Maybe that's what puzzles me the most: What were they thinking? Did they think he'd get lucky and make it through all right? Under those circumstances? I think my own faculties are doing quite well, but I sure wouldn't trust myself standing under hot lights for 90 minutes beginning at 9 o'clock at night. And those closest to me know better than to expect much sense out of me at that hour.

- Here's where my cynical brain takes over: Was it a purposeful take-down of the president? Were they convinced he couldn't win in November and couldn't find a more graceful way of getting rid of him? But if they wanted to get rid of him, why did they work so hard to make sure he had no opposition in the primaries? I would happily have voted for a better choice if they had given me a chance.

- If President Biden is not competent to run for the office again, is he competent to be in the office now? What about for the last four years? I know I said I understand not being competent to make sense after 9 p.m. but can't we expect more of our commander-in-chief? What if "one bad night" occurs when we're on the brink of war?

- (Not, mind you, that I want to see Biden removed. I always thought Kamala Harris was a great choice for vice president because she served him well as both assassination and impeachment insurance.)

- What unelected and unknown person or committee has been running the country for the last four years? Do they hope to continue in that role?

- Are they using Kamala Harris as a placeholder until they can manoeuvre someone better into the nomination, or do they think she will be as manipulable as Biden?

- If this is a conspiracy, it sure seems as if it could have been done better. I've always said that there is no need to cry "conspiracy" when events can just as easily be explained by plain human stupidity. Or maybe the conspirators, whoever or whatever they may be, are far smarter than I am and are playing a long game whose end I cannot see.

Even the Mad Hatter's Tea Cup ride never left me this dizzy and disoriented.

You all know I can't resist commentary. So why have I been so silent—or, rather, why have I been making unrelated posts—when so much of import has been happening?

One word: Family.

Eleven out of our 13 grandchildren, along with their associated parents and extended family, were together for the first time since 2017. They live an ocean apart from each other, and this was a very special time that could have trumped anything but the Second Coming.

My recent posts were written weeks ago, to be posted automatically while my priorities were elsewhere.

As I work on catching up, I'll jump back in—not with any particular order, but from the heart.

I can't wait to see one of these new signs the next time we return to Florida by car.

I'd like to add, "Let's Keep It Free" to the sign, because freedom is a fragile thing. (Quoting Ronald Reagan, though I'm sure it wasn't original with him.)

At the beginning of this year, I did the unthinkable. At least, for me, it had been unthinkable for over half a century. Nonetheless, early in 2024, I changed my political party affiliation. It was a dramatic change that had been brewing for a very long time.

I've never been a party person. I like my encounters with people to be in small, quiet groups, centered around discussion, homemade music, and food—a scenario that many people today would not even recognize as a party.

There's another kind of party I'm not happy with: political parties. I believe—I have always believed—that the best person for the job should get my vote. (Or sometimes, sadly, the least bad.) I've always registered with a party, however, in order to have a say in the primary elections.

My parents never talked much about politics. I vaguely knew that they that they were not party-liners, but voted for whomever they thought best for the job, though they never shared who that might be.

When it came time for me to register to vote, they didn't blink an eye when I chose to become a Democrat, although I knew they were registered Republican. All my father said about it was that I was consigning myself to having no say in local elections, which at that time and in that place were always decided by the Republican primary. But I was a student—what did I care for local politics? Besides, almost all of my friends were becoming Democrats, and we had campaigned enthusiastically, if uselessly, for Hubert Humphrey against Richard Nixon, even though we weren't at that time old enough to vote. There I was, proudly proclaiming my independence by doing exactly what my peers were doing. But such, ofttimes, is youth.

Besides, the Democrats seemed to be concerned about many of the same things that were important to me: family, the environment, women's rights, caring for others, and freedom of thought. (How and when the Democratic Party betrayed my trust in all these areas is a subject for another time.) What the Republicans were concerned about was largely a mystery to me.

I had chosen to align myself with the Democrats, but that didn't mean I voted the party line. My parents were right about that. I always thought the old, mechanical voting machines were bizarre, because one feature was that you could vote for every candidate of a particular party by throwing a single lever. Who would want to do that? I registered as a Democrat, and voted as I pleased. After we married, Porter and I found it particularly useful to have one of us registered as a Democrat, and the other as a Republican, as it gave us votes in each political primary. (We've always lived in states that did not allow non-party members to vote in party primaries.) It also signed us up for information from both parties, which helped with decision-making, though it also more than doubled our junk mail, and e-mail-, text-, and phone spam.

I've never had any trouble getting along with both Republicans and Democrats (as well as the odd Independent), as people. As long as you ignore what they say on certain subjects, and keep your mind on what they do and are, our friends, neighbors, and relatives are almost all good folks, the kind you want to have around.

And so it went for over 50 years.

It didn't take me more than a decade to realize that while the Democrats largely said the right things, their policies often accomplished the opposite of what their words indicated. I'm old enough to have seen in real time the damage Lyndon Johnson's policies did to impoverished urban families. Many of the homeschooling movement's leaders were left-leaning, yet the Democratic Party remained solidly in the pockets of the teachers' unions. And they kept dragging women's rights, care for the environment, and other issues in decidedly wrong directions.

Still, it never occurred to me to change parties. Those were the days when the causes that I worked for (such as conservation, and food, educational, and medical freedom) were very much bipartisan, respectful (for the most part), and even joyful in our common causes—we were too small not to get along. I stuck with the Democrats, and voted faithfully in all the primary elections, hoping to slow what appeared to me to be serious decay.

I'll admit to being far too lazy when it comes to politics. Actually, I hate politics. However, as I believe Pericles said, "Just because you do not take an interest in politics doesn't mean politics won't take an interest in you." I vote faithfully, and hopefully at least somewhat intelligently, though I'm far from being as informed as I could be. I write to various elected leaders, but only rarely. I need to do better. All that is to say that was doing a mediocre job, just going along and getting along.

Then along came 2016. That's when I finally decided that I should actually read the platforms of both the Republican and the Democratic parties. To see what they claimed to stand for, and what they hoped to accomplish.

And I was shocked. How much had changed! Maybe my own Democratic Party had gradually evolved to its present state—as I said, I hadn't been paying much attention to the official stance, just individual candidates. Of course there were things in the Republican platform I didn't care for; that didn't surprise me in the least. But the Democratic platform nauseated me. Was this what I had been supporting all those years? I don't regret the people I voted for, not really—people are almost always better in person than the ideals they claim allegiance to. But how could I remain officially in a party whose goals were so antithetical to my own deeply-held beliefs? What had happened to my party? Granted, in the interim I had pretty much done a 180-degree spin on gun issues, but aside from that, my thoughts had refined, but not substantially changed.

Why not become a Republican at that point? (Other parties were out of the question; I still wanted to vote in the major primaries.) Why did I remain a Democrat? Hope, partly. Hope for change from within; I know I was far from the only Democrat who thought the party had gone off the rails. And there's both power and hope in being able to say, "Not all Democrats believe in X; I'm a Democrat and I disagree."

But mostly, I confess—it was inertia. After all, just being a party member didn't stop me from voting as I pleased. The only time I regretted not switching was when I couldn't vote for Ben Carson. But Porter didn't get to vote for him either, since he was out of the race when Florida held its primary.

Ah, primaries. That, actually, was what kicked me into leaving the Democratic Party. I had been looking forward to voting in this year's presidential primary election, but Florida's Democratic Party proceeded to disenfranchise me. "We will have no primary; we have decided that Joe Biden will be our candidate, and the people will have no say in the matter." That attitude ticked me off almost more than the important issues.

So this life-long Democrat became a Republican, and happily voted in their primary.

In a way, nothing has changed. I will still vote for the person I think will do the best job, no matter what letter they put after his name. (Though I confess the D's have a much better chance in local and state elections than nationally.) But it's time to take a stand, and I can no longer tolerate having my name on the rolls of those who ostensibly give their approval to what the Democratic Party has become.

Actually, I took that stand months ago, when I switched parties; it just took this long to find the words to explain why.

The Kindle version of Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.'s blockbuster book, The Real Anthony Fauci, is currently on sale at Amazon for $1.99. I don't thnk Kennedy is the right man to be president at this point, though I would have voted for him in the primary, if I'd had the chance. But that doesn't change the fact that I believe everyone should read his book.

Here's my review, and a couple of short videos about the book. If you're at all interested, you can't beat the price.

Little did I know, that even as I was writing my post about the recent presidential debate, Bret Weinstein and Heather Heying, of the DarkHorse Podcast, were busy wrestling with some of the same questions. Specifically, How could those close to President Biden not have known how bad he would appear in such a situation? and Who has really been running the country all this time? I saw their podcast the next day, and now must share it.

(I know, lots of people, all over, have been talking about the debate and what the Democratic Party is going to do, but most of them seem to me to be missing the important parts.)

As usual, there's much of interest in the whole video of more than two hours, and I list below the timestamps for those who want them. The actual debate commentary is short, between 1:23 and 1:30, but if you're at all interested, I would strongly recommend you listen to it in context, from 1:10 and 1:51.

Timestamps:

(00:00) Wait

(11:41) Welcome

(14:16) Sponsors

(22:46) Thomas Paine's Common Sense

(39:56) Excerpt 4-6

(50:56) Indifference to suffering

(01:10:31) Declaration of Independence

(01:18:01) Defining Deep State

(01:23:24) Post debate discussion

(01:30:01) Revisiting the 2020 election

(01:34:16) Hunter Biden's laptop and inverse institutions

(01:45:51) Certainty yet dead wrong

(01:51:36) Team GB Rugby and body positivity

(02:02:31) Caitlin Clark and attention communism

(02:16:11) Wrap up

Somewhat against my better judgement, I watched the presidential debate. I knew that once people started talking, I'd be tempted to say something about it, so I'd better have first-hand knowledge.

I cannot understand what all the fuss is about since then. Why it seems to have been such a surprise to so many people.

But first, my own reactions.

- I have no idea why Trump agreed to the debate. It was held on clearly hostile territory (CNN, with the moderators manifestly against him, politically). The format did not play to his strengths, i.e. without a crowd to play to and be encouraged by. He was already ahead in the polls, so on the face of it, the debate was riskier for him than for Biden.

- The moderators did a better job than I expected of keeping their biases in check, so I give them some credit for that. But they did a lousy job of keeping the debaters in check. They weren't moderating anything, just reading questions (that weren't answered).

- Can we make it a rule that no one can run for president without first having participated in debate in high school? This was the second-most ridiculous so-called debate I've ever seen. Not that I've seen very many, but I have some idea of how the participants are supposed to behave, and this was not it.

- I found Trump more cogent and intelligent than Biden, certainly, but neither one of them answered the questions! They poked back and forth at each other like a couple of rude middle school boys, and said what they wanted to say irrespective of the questions. I wanted to hear about issues—they wanted to hammer on and on about how terrible the other guy was.

- Biden was so embarrassing—worse, he was really scary. The hatred I saw in his eyes when he looked at Trump was like a kick in the stomach, the same as I saw during his Independence Hall speech. Then again, I may have been misjudging his expression; I couldn't help wondering if he has had a small stroke, given the asymmetry of his smiles.

- Trump could have made all his points about how badly Biden has done by instead being positive about what he will do to fix the problems. He shouldn't have stooped to the level his enemies were hoping for. This argument over who was the worst president in American history? Absurd, and middle-schoolish at best. (I think they're both wrong.)

- Trump also should not have let Biden play the Reagan card. As incapacitated as he was, Biden managed to maneuver Trump into saying how terrible America is, and how much trouble we're in (Carter's position), while portraying himself as the positive, optimistic candidate (Reagan's). Anyone who has been looking at the last four years with open eyes knows better, but those aren't the people Trump needs to reach.

- The exclusion of Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. was inexcusable. He would have made the debate much more interesting, and quite possibly would have set an example by actually answering the questions asked. It's not that I think he's really a viable candidate—I agree with Mark Groubert that he (and we) would be much better off if he quits his presidential campaign and runs instead for California's governor or senator position, for either of which he should be a shoe-in. But his ideas are rational and important, and they deserved to be heard in the context of the other participants' answers.

Most Trump supporters apparently think that he won the debate. If so, it was only because Biden clearly lost. There's a reason why I generally avoid listening to politicians talk. When I hear them speak, I despair. It's when I look at what they have actually done that I feel I can make an intelligent voting decision.

What really puzzles me is the shockwave that has been rocking the Democratic Party because of Biden's performance. Really? Who can be shocked? Biden's cognitive decline was visible at least as far back as 2020, and has gotten progressively and significantly worse. It's long past the point for giving him the benefit of the doubt. Maybe the casual citizen, who only hears sound bites and sees highly edited videos, could have missed it, but the party movers and shakers? The news media who edited the video footage? Those closest to him in the government? How could they possibly have been surprised?

Is it all an act? Did they know, and plan to use what they expected to be a disaster of a debate to give them an excuse to manipulate a more reliable candidate into being their presidential candidate? Did they somehow hope Biden could hold things together and come across better than he did, to win the election and establish himself as president just long enough for the vice president to take over? Did they really delude themselves into believing he was okay—until the debate made it impossible to deny? I have no idea; none of it makes sense to me.

I am left with two questions.

- What is the Democratic Party going to do? Prop up Biden and hope he can survive until he is sworn in, then take him out as gently as possible? Or go through whatever machinations they can to put forth an alternate presidential candidate, one chosen in the old-fashioned way, by political hacks in smoke-filled back rooms? (Here in Florida, we didn't even have a primary to vote in.)

- Who has really been running the country for the past few years? Whatever person, or cabal, it might be, they were not elected to this position, and have been doing a spectacularly terrible job of it. How do you vote out someone who was never voted in?

Finally, a warning for Republicans: Be careful what you wish for. "It can't get worse" does not have a good track record.

Back in January of this year, Jordan Peterson and Tucker Carlson answered a question about where they saw 2024 headed. Here we are in the middle of the year, and what they have to say is still relevant. This is a 10-minute excerpt from a much longer show, which I'll say upfront I haven't seen. But, being a very much johnny-come-lately fan of both men, I appreciate their differing points of view—and especially how they come together at the end.

Fathers, we need you. The future of the world depends on you. Well, no—not entirely. But the great Father upon whom all depends invites you to be part of His work. Understand the truth of the dark times Carlson foresees, and take hold of Peterson's optimisitic solution.

Happy Father's Day!

On June 8, 2023, we were in Gdansk, Poland. It was just for a day, and Gdansk was not for the most part a particularly pleasant city to visit. Poland has had more of a struggle than, say, East Germany in the aftermath of winning its freedom back in the 1980's, and Gdansk is far less clean and modern than the former East Berlin.

However, Gdansk was as moving and as inspiring as Berlin, where we had touched remnants of the Berlin Wall and stood at the site of Checkpoint Charlie. Arguably, Poland led the revival that liberated Eastern Europe, and it was an awesome experience to see the Gdansk shipyard where the Solidarity Movement had its beginnings.

An unexpected additional blessing was that we were in Gdansk for the Feast of Corpus Christi, and we were vividly reminded that in Poland during the Soviet era, the Catholic Church resisted the assaults on Christianity more successfully than in most other Eastern European countries, and that the Church's leadership and courage was a major factor in their liberation.

It came as a complete surprise to us, walking around the city, suddenly to find ourselves in the middle of their Corpus Christi Day procession, and what a moving experience that was. Even with all the tourists (like us) milling around and taking pictures. (I was not so moved as not to notice the very clever sound system, with speakers strategically placed throughout the procession to keep everyone together. I've been in too many much, much smaller Palm Sunday services, in which the tail of the procession gets hopelessly and painfully out of sync with the head, not to appreciate this innovation.)

I have nothing to improve on the Memorial Day posts I have made in the past, except this thought that has been on my mind lately.

Perhaps the best way we can honor those who stood bravely "between their lov'd home and the war's desolation" is to stop taking for granted the freedom they gave their lives to protect. Let's not defile their sacrifices by treating lightly the present-day assaults on our sacred liberty and Constitutional rights, but work to preserve what was gained at so great a cost.

Oh! thus be it ever, when free men shall stand

Between their loved home and the war's desolation!

Blest with vict'ry and peace, may the heav'n-rescued land

Praise the Pow'r that hath made and preserved us a nation.

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto: "In God is our trust."

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave!

Not long ago, I ran down an interesting rabbit hole.

As a genealogy researcher, i have both an interest in and a knack for finding people and stories. Today a friend's casual comment on a completely unrelated subject led me eventually this meme on Facebook:

It caught my eye, both because it speaks an important truth and even more because I knew a friend who would especially appreciate it. But I'm also researcher enough not to pass something like this along without knowing more about the context. So I did a Google image search for the picture.

That turned out to be so much easier than most of the image searches I do. I've mentioned before that I'm organizing my father's journals, and also the old photographs from the same time period. Since most of the labelling on the photos is missing or minimal, Google Lens has been of immeasurable assistance, though a good deal of detective work is still necessary.

The context of this photo popped up immediately. (Well, almost—I'll get to that caveat in a moment.) Wikipedia has the exact picture, and helpfully explains that it is a photo of "Polish Jews being loaded into trains at Umschlagplatz of the Warsaw Ghetto, 1942." On this, I think Wikipedia can be trusted. So it's legit.

But I mentioned that the search wasn't exactly as easy as I had implied. That's where this rabbit hole got especially interesting.

Google refused, at first, to show me any results, as they were likely to be "explicit." I don't know about you, but to me, that designation implies that the results would show me pornography or graphic violence or other obscenity. Granted, the ideas and actions represented by that photo are obscene enough, but not the photo itself, which legitimately documents an important and dangerous time period.

In order to see it, I had to turn off Chrome's "Safe Search" feature, which I had heretofore assumed was there to filter out graphic sex and violence. The feature manages to discern the difference between pornography and the naked ladies featured in art museums; why is historical data a problem? Some day I may get curious enough to check out other browsers. Anyone here have experiences to share?

On top of that, I learned that what I was seeing was someone's second attempt at sharing this meme, Facebook having taken down the first. What Facebook found offensive I do not know. I'm tempted to post it directly myself and see what they do, but I'll try cross-posting this first. I generally just post links to Lift Up Your Hearts! when I want to share them on Facebook, and I doubt the FB censors will dig that deep. We'll see.

Here's why it matters: Knowledge of history is essential. My 15-year-old self would have choked on that, as of all the history classes I endured, there was only one I thought worthwhile. (I take that back; there was also the unit on Native Americans back in fourth grade, which was pretty cool.) Nonetheless, one of the lessons I remember best from all my years in school is that one of the clearest characteristics of a totalitarian régime is its attempts to cut its people off from their own history, whether by re-writing it (à la the novel 1984) or by changing the language (whatever the benefits of simplified Chinese, it has greatly limited the people's ability to read historical Chinese documents), or by simply encouraging an atmosphere of ignorance.

The meme, it turns out, is as much about the First Amendment as the Second.

I've long known, and been troubled by the fact that nearly all of our vitamin C comes from China.

It's not that I'm against trade with China. When two powerful enemies have a thriving trade relationship, they are much less likely to seek to blow each other to bits.

On the other hand, China's terrible reputation when it comes to health and safety, environmental, labor, and human rights concerns really ought to be taken more seriously, especially when it comes to what we ingest.

I'm sufficiently convinced of the value of vitamin C in preventing/mitigating illness that it's a regular part of my health routine. As I said to one of my doctors, who agreed that he followed a similar philosophy, "I don't care if it's only the placebo effect—the placebo effect itself turns out to be effective about a third of the time." For that reason, I've been seeking a non-Chinese alternative to vitamin C.

I think I've found one: LifeSource Vitamins.

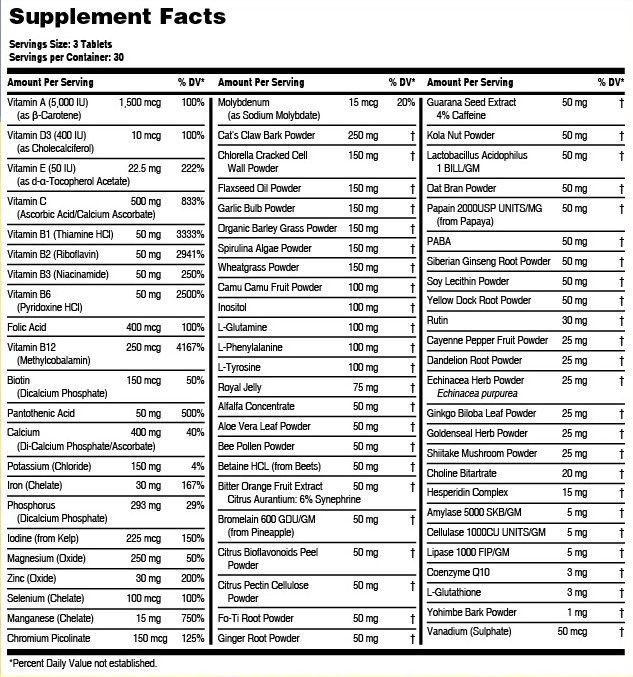

It from no one's recommendation, no advertisement, nothing but a simple internet search on "vitamin c not from China." So this is not a review, nor an endorsement of all they offer. But their vitamins do not come from China, and what's more, they're local (just across town in Winter Park). That was good enough for me to give them a trial. I ordered their 500mg vitamin C, and also decided to try some multivitamins and minerals. The latter is a whole lot more than just vitamins; I reproduce the back label here, not only for your information, but so I can easily read it when I want to; to read the actual label I have to resort to a magnifying glass.

I have no idea what good all these various things are supposed to do for me. (Chlorella Cracked Cell Wall Powder, anyone?) I'll let you know if I can suddenly leap tall buildings in a single bound. I'm more interested in the more ordinary ingredients, and will note that the "serving size" is three tablets (you're supposed to take one with each meal), so if some of these percentages look a little high to you, it's easy to take just one.

And that's another thing I like about these vitamins: they are easy to take, period. I don't generally have trouble swallowing pills, but often have a real problem with vitamin C tablets. For whatever reason, they sometimes stick in my throat, causing me to choke and/or vomit. It's not pleasant to feel I'm rolling the dice everything I swallow a vitamin. These vitamin C tablets, however, don't have the customary rough coating, but are smooth—and slide right down.

As I said, this can hardly be a review of the product at this point—why do companies ask for reviews from people who can't possibly have enough experience to say more than, "Yep, it arrived in good time and the packaging was intact"? But I asked for non-Chinese vitamin C, and I'm grateful to have found some.

So I'm passing along the information the best way I know.

.jpg)