I don't always understand Jordan Peterson, nor do I always agree him, but he is always interesting and makes me think. Here he manages to ponder the causes of anti-Trump extremism, the fears of Trump voters, the fundamental natural resource of Western civilization, and the terrifying erosion of trust he has observed over the last five years, all in three minutes.

It wasn't long ago that I wrote the following:

People who buy extra toilet paper, or cans of soup, or bottles of water for storage rather than immediate consumption are not hoarding, they are wisely preparing for any interruption of the grocery supply chain, be it a hurricane, a pandemic, civil unrest, or some other disruption. As long as they buy their supplies when stocks are plentiful, they are doing no harm; rather, they are encouraging more production, and keeping normal supply mechanisms moving.

Plus, when a crisis comes, and the rest of the world is mobbing the grocery stores for water and toilet paper, those who have done even minor preparation in advance will be at home, not competing with anyone.

It's always fun to come upon someone who not only agrees with what I believe, but says it better and with more authority. Lo and behold, look what I found recently, in Michael Yon's article, First Rule of Famine Club.

Hoarders, speculators, and preppers are different sorts, but they all get blamed as if they are hoarders. Hoarders who buy everything they can get at last minute are a problem.

Preppers actually REDUCE the problem because they are not starving and stressing the supplies, but preppers get blamed as if they are hoarders.

Speculators, as with preppers, often buy far in advance of the problems and actually part of the SOLUTION. They buy when prices are lower and supplies are common. Speculators can be fantastic. When prices skyrocket, speculators find a way to get their supplies to market.

I hadn't thought before about speculators. I'd say their value is great when it comes to thinking and acting in advance, but the practice becomes harmful once the crisis is already on the horizon. Keeping a supply of plywood in your garage and selling it at a modest profit to your neighbors when they have need is a helpful service, but buying half of Home Depot's available stock when a hurricane is nearing the coast is selfish profiteering.

Permalink | Read 889 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Food: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Here I Stand: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Do you have books from your childhood that have been loved into reality, like the Velveteen Rabbit? Think twice before trading them for newer editions. The same advice holds for any book you value.

I've already been hanging on for dear life to my copies of C. S. Lewis' Narnia books with the original American text. The modern, modified versions are interesting—I believe they are the British versions—but I still prefer the American versions, which contains Lewis' later revisions. What I really don't like about the currently-available books is the way they are numbered in chronological order, rather than publication order, as I strongly believe that they make much more sense in publication order.

Far more important than these minor changes, however, is what is being done to books now. This Natural Selections essay, "The Age of Censorship," gives some examples of what has been done to the new editions of Roald Dahl's works.

Many of the changes are of a type. For instance, more than a dozen instances of the word “white” were changed. White was changed to pale, frail, agog or sweaty, or else removed entirely. Because, you know, a color can be racist.

In one book alone—The Witches—The Telegraph counted 59 new changes. These run from the banal—”chambermaid” is replaced with “cleaner”—to cleansings that appeal more directly to modern pseudo-liberal sensitivities. The suggestion that a character go on a diet, for instance, is simply disappeared. And this passagage,“Even if she is working as a cashier in a supermarket or typing letters for a businessman,” has been changed to, “Even if she is working as a top scientist or running a business.”

It’s hard to know what even is believed by the censors who made these changes. Do they mean to suggest that nobody should go on a diet, or that no woman has ever worked as a cashier or a typist? And what, pray tell, is a “top scientist.” I’m guessing that none of the censors could provide a working definition of science, but that when asked to conjure a scientist up, they imagine someone with super science-y accoutrements, like a white lab coat and machines that whirr in the background. Sorry, that would be a pale lab coat.

Dahl's final book, Esio Trot, contained this passage, not in the text but in an author's note: "Tortoises used to be brought into England by the thousand, packed in crates, and they came mostly from North Africa." This was replaced by: "Tortoises used to be brought into England by the thousand. They came from lots of different countries, packed into crates."

I'm beginning to suspect that the real reason for these changes is to dumb down the language, the quality of the writing, and the readers.

It's not just children's books that are being rewritten. This Guardian article explains how Agatha Christie's books have been subjected to the censors' edits.

Among the examples of changes cited by the Telegraph is the 1937 Poirot novel Death on the Nile, in which the character of Mrs Allerton complains that a group of children are pestering her, saying that “they come back and stare, and stare, and their eyes are simply disgusting, and so are their noses, and I don’t believe I really like children”.

This has been stripped down in a new edition to state: “They come back and stare, and stare. And I don’t believe I really like children.”

Really? Is there some sort of requirement that when one dons a censor's hat, one must forget how to write interesting prose?

Back to Natural Selections.

There are many things troubling about the creative work of an author being changed after his death. It interferes with our understanding of our own history. We live downstream of our actual history, which did not change just because censors got ahold of our documents. Having the recorded version of history scrubbed interferes with our ability to make sense of our world.

Post-mortem revisions are also bad for art. These edits raise questions of creative autonomy. Of voice. Of what fiction is for. Fiction is not mere entertainment. Fiction educates and uplifts, informing readers about ourselves and our world, and also about the moment in time that the work was created.

When our children were young, I noticed that the newer version of Mary Poppins had been scrubbed of a chapter that was decidedly inappropriate to more modern sentiments. I didn't think too much about it at the time. But now I'm utterly convinced that even young children deserve to know—need to know—that not all cultures and times have had the same values and priorities that we do now. That while we may find other beliefs and practices horrifying, many other cultures would find our own beliefs and practices equally horrifying. What's more, and most important of all, that people in the future will look at us with the same patronizing disgust with which we see our predecessors. We are not the pinnacle of civilization.

That's an excellent topic of conversation for parents and their children, and what better place to start than with a beloved book?

Here's yet another reason why I prefer to judge politicians by what they do rather than what they say:

Porter was listening to Vice President Harris speak. As I walked by his office, I heard her say, "For the past 10 years we have had a president who did his best to divide our country." I fully admit that that's a paraphrase, because I don't remember word-for-word, but I assure you that was the sense and the number is correct.

I can't just walk away from something like that, even though yelling at the screen didn't do the least bit of good. Let's do the math.

Ten years ago, we were more than halfway through 2014, and Barack Obama was president. Donald Trump took office in 2017, then Joe Biden in 2021. That's four years when Trump was president, with roughly two and a half of Obama and three and a half of Biden. So, four years of the person she vilifies, bracketed by six years of those she admires. Shouldn't the latter take 60% of the blame for the mess she claims was made of the past ten years? She, personally, should take 35%, since she was second-in-command, and by her own admission highly influencial in the decisions that were made during that much of the time.

I didn't realize how much power a president has in deciding who gets protection from the Secret Service and who does not.

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. had repeatedly asked for Secret Service protection as a presidential candidate, and was repeatedly denied—until the attempted assassination of President Trump made it politically inexpedient not to grant the request. But as soon as Kennedy decided to remove his name from the ballot in 10 states, the protection was immediately removed, even though his campaign is still active in the remaining states.

This action is not surprising from an administration whose primary strategy appears to be to do everything possible to remove its competitors from the ballot, from the Democratic primaries to November's election.

But it was not always so.

Some claim that Secret Service protection is only for viable candidates (they get to define the term), and typically only within 120 days of the November election. But before the 1980 election, Jimmy Carter made sure that Ronald Reagan, Ted Kennedy, and his other opponents were protected by the Secret Service long before the election; in Ted Kennedy's case it was for more than a year, beginning before he officially announced his candidacy.

The president can make it happen if he wants to, and Jimmy Carter acted from higher principles than we're witnessing here.

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.'s historic speech brought to mind this entry from my father's journals.

June 5, 1968

For the first time in months I turned on the radio during breakfast this morning to hear the outcome of the primary election in California, and learned with a shock that Senator Kennedy had been shot. It seems inconceivable that so many people have taken to shooting people they disagree with, and that to so many the end seems to justify the means. Somehow, things have got to get back on the right track.

I just watched Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.'s Phoenix speech live, and admit I was transfixed by every word. Politicians, it turns out, can still speak intelligently, rationally, and with substance!

It's not as long as it looks (90 minutes)—the video says 90 minutes, but his speech doesn't start till 41:29. I highly recommend it.

Thanks to all the leaks, everyone was expecting Kennedy to endorse Donald Trump. And that he did, without drama, but with conviction, because he believes he can worth with President Trump, especially on the issues that drive his own vision: freedom of speech, war policy, and the unspoken epidemic of chronic disease in America. On these issues Kennedy spoke at length from his heart, taking advantage of this "bully pulpit."

I strongly recommend taking the time to listen.

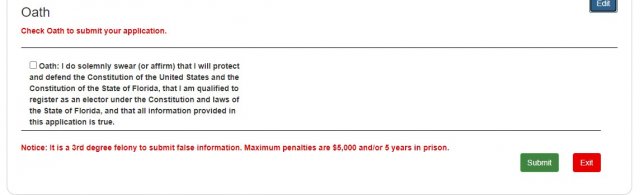

I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will protect and defend the Constitution of the United States

This is what I had to agree to when I changed my political party affiliation several months ago. I don't remember it from Pennsylvania, New York, or Massachusetts, nor from the two other times I've registered to vote in Florida. I knew it to be required of the president and other high-level officials, but didn't know it applied to ordinary voters. Maybe it's new; maybe I just missed it or am remembering poorly. Whatever the case, it's a good idea, and I'm taking it most seriously.

The least I can do is vote with my mind, my heart, and my conscience.

The Constitution of the State of Florida is a bit more fragile, harder to protect and defend, because it's so easy to amend. But I'll do my bit by voting down some truly egregious constitutional amendments on the ballot this year.

Last night, I listened to most of the conversation between Elon Musk and Donald Trump, and this morning I picked up the 30 minutes remaining when I went to bed. I assume they were on Pacific Time, but we are not, and there was nothing in the conversation that couldn't wait till the morning.

I didn't know about the event till yesterday, and might have been intrigued enough to listen. As Musk himself said, you don't get a good feel for a person through campaign speeches, interviews, or even debates. He wanted a free-ranging conversation between himself and Donald Trump, and I thought that could be interesting.

What clinched my participation, however, was a question from yesterday's White House press briefing. I don't know the name of the journalist, or what organization he represents, and the C-Span cameras remained focused on Ms. Jean-Pierre, but you can hear well enough. The question begins at 20:00, if you want to confirm it, but this is from the transcript, with a few minor corrections to make it more readable. (emphasis mine)

Journalist: Elon Musk is slated to interview Donald Trump tonight on X. I don't know if the president is going to—feel free to say if he is or not—but I think that misinformation on Twitter is not just a campaign issue. It's an American issue. What role does the White House or the President have in sort of stopping that or stopping the spread of that or sort of intervening in that? Some of that was about campaign misinformation. But you know, it's a wider thing, right?

Jean-Pierre: You've heard us talk about this many times from here about the responsibilities that social media platforms have when it comes to misinformation, disinformation, [I] don't have anything to read out from here about specific ways that we're working on it, but we believe that, that they have the responsibility. These are private companies, so we're also mindful of that too. But look, it is, I think it is incredibly important to call that out as you're doing. I just don't have any specifics on what we have been doing internally as it relates to the interviews. It's not something that I'm tracking and I'm sure the president's not tracking it either.

What did I just hear? A jounalist calling for the President to stop Musk and Trump having a conversation and sharing it on X with the American (and worldwide) public, First Amendment be damned? Of course I had to listen in!

It turned out to be a rather exciting event even before it started, because I couldn't get in to the conversation. Now, I had joined X back in 2015, when it was still Twitter, inspired by the Arab Spring and the realization that social media might be the best way to communicate in times of crisis. But I never did much at all with it, just kept it in my back pocket. So I figured my problems were just because I didn't know what I was doing.

Except that no one else could get in, either. It was rather fun, actually, trying one source after another, each one scrambling to see what was going on.

Just as the conversation was about to begin, X's servers had been hit by a massive DDOS (distributed denial of service) attack, presumably by someone who was even more disturbed by the prospect of Musk and Trump talking to the world than the anonymous journalist.

Do I really think that our government was behind the DDOS? No, though I wouldn't put it past them. But the coincidence of the journalist's question, and Jean-Pierre's non-specific "what we have been doing internally as it relates to the interviews," is noted. Hopefully we will eventually find out what happened. (Personally, I hope it was some prodigy hacker eager to test his cyber muscles against Elon Musk.) For now, it is enough that the busy computer bees at X managed to get out from under the problem quickly enough, and the show went on.

This link should take you to the full three-hour recording. No doubt there will be highlights or summaries to come, but there's a good deal of value to original, unscripted, unedited data. Collected excerpts always reflect bias one way or another. Judge for yourself if there was anything so frightening you think we need to abandon our Constitution. UPDATE: Musk just posted a link to a version with higher quality audio. It's also only two hours instead of three, but at a quick glance appears to be complete. I have no idea how they did that, but it does like a more approachable conversation at 2/3 the length!

Was it worth listening to? I think so. Was it spectacular? No. Was it frightening? No. Was there anything there at all that could possibly have been worth throwing out the First Amendment, let alone so casually? Absolutely not.

At first the conversation was actually boring. As impossible as this seems for two such men, both Musk and Trump seemed a bit nervous. After touching briefly on the near-assassination, Musk merely let Trump speak away, in whatever direction he wanted to go. Not surprisingly, it sounded like a campaign speech, with far too much emphasis on the flaws of his opponents and the wonderful things he did when he was in office. For all I can see, he's right, but I'm tired of hearing it. He did much better when he focused on the positive things he plans to do if he gets elected this time.

As time went on, however, Trump's obvious excitement at an "interview" in which he was allowed to keep talking wound down, and both he and Musk relaxed. From then on, the conversation became worth listening to. Again, there was nothing spectacular about it, but free-ranging conversations among highly intelligent people who respect each other are almost always interesting.

I think the conversation was a good idea, and I hope Kamala Harris takes Musk up on his invitation to do the same.

I'm willing to bet that none of you woke up this morning wondering what all the fuss was about the Supreme Court's recent "Chevron" rulings. However, for those of you who might have at least given the question a passing thought, here's a good article by John Mauldin and Rod D. Martin, explaining how important these decisions are in restoring to elected officials some powers that had been ceded to unelected, and largely unaccountable, federal bureaucrats. (You should be able to read the article at that link. One of the things I like about Mauldin is that while you're strongly encouraged to subscribe, there's a lot that's not behind a pay wall.)

The Supreme Court’s overturning of Chevron was an early Independence Day gift. Chevron stood for an imperial bureaucracy, neither responsible to the people nor accountable to anyone, a priesthood of experts pursuing what Thomas Sowell called “the vision of the anointed,” interpreting, adjudicating, and above all, making the laws we must live by, however they saw fit.

Last week, in their Loper and Jarkesy rulings, the Court overturned that half-century travesty, partly upending the statist technocratic order and, at least to a degree, replacing it with the Constitutional vision of the Founders.

Take the Environmental Protection Agency as one example. The EPA, like countless other agencies, concentrates the powers of all three branches of government in its agency administrator, the de facto dictator. The agency makes law, and its lawmakers work for the administrator. The agency enforces the laws that it makes, and those enforcers also work for the administrator. Worse still, the agency employs a small army of Administrative Law Judges, or ALJs, whom it may haul you in front of whenever it chooses. They work for the administrator too.

All of this is a grossly unconstitutional violation of the separation of powers. It eliminates virtually all checks and balances. And the Chevron Court acknowledged that, to a degree: It said that by 1984, things had been done this way so long that it would just be too disruptive to change things.

In short, Chevron established constitutionality by longevity. You can apply that logic to Plessy v. Ferguson which said in 1896 that segregation was legal within limits and tell me whether you think it’s a good idea.

Under Chevron an agency could sue you in front of its own judges, over its own made-up rules, enforced by its own bureaucrats, and you had no right to an appeal. You didn’t even get a jury of your peers.

At every step of the process, Chevron replaced “government by the people” with that priesthood of experts, those who must simply be trusted to be benevolent, all-knowing, and true.

It’s worse. Increasingly, agency regulations are “strict liability,” which means that your intent doesn’t matter. By this standard, an accidental killing becomes murder. And speaking of murder, agencies issue not just civil but their own criminal laws, by some estimates as many as 300,000 separate agency-made offenses, all adjudicated solely by their own ALJs with no juries and no possibility of appeal.

These out-of-context quotes are just a taste; if they intrigue you, you might enjoy the whole article.

Here's a question I'd like to ask of political pollsters:

What is the ideal position for a political candidate in the polls, at various times before an election?

Clearly, to be leading in the polls on Election Day (or whatever passes for Election Day in these days of early voting and mail-in ballots) is a good thing. But what about earlier? To be doing well at any point feels great, and can boost support due to the "to him who has, more will be given" effect. People like to be on the winning team, and tend to flee people they feel can't win.

I think there's more to it than that. The following excerpt is from Robert A. Heinlein's Citizen of the Galaxy; it has haunted me since I first read it in elementary school. (emphasis mine)

Weemsby stood up and looked happy. "In my own person, I vote one share. By proxies delivered to me and now with the Secretary I vote—" Thorby did not listen; he was looking for his hat.

"The tally being complete, I declare—" the Secretary began.

"No!"

Leda was on her feet. "I'm here myself. This is my first meeting and I'm going to vote!"

Her stepfather said hastily, "That's all right, Leda—mustn't interrupt." He turned to the Secretary. "It doesn't affect the result."

"But it does! I cast one thousand eight hundred and eighty votes for Thor, Rudbek of Rudbek!"

Weemsby stared. "Leda Weemsby!"

She retorted crisply, "My legal name is Leda Rudbek."

Bruder was shouting, "Illegal! The vote has been recorded. It's too—"

"Oh, nonsense!" shouted Leda. "I'm here and I'm voting. Anyhow, I cancelled that proxy—I registered it in the post office in this very building and saw it delivered and signed for at the 'principal offices of this corporation'—that's the right phrase, isn't it, Judge?—ten minutes before the meeting was called to order. If you don't believe me, send down for it. But what of it?—I'm here. Touch me." Then she turned and smiled at Thorby.

Thorby tried to smile back, and whispered savagely to Garsch, "Why did you keep this a secret?"

"And let 'Honest John' find out that he had to beg, borrow, or buy some more votes? He might have won. She kept him happy, just as I told her to."

A really commanding lead can discourage competitors from pouring money and effort into a losing cause. But somewhere in between that kind of lead and the bottom of the heap there's a point—I'm going to call it the Garsch Point—where a lead is dangerous. Two terrible things can come into play:

- A candidate's own supporters can become complacent, let down their guard, and like the overconfident hare, risk losing to the lagging but persistent tortoise.

- A zealous opponent, who would rather win honestly, may be tempted to resort to nefarious means of helping himself to victory. After all, when you're fighting infidels, it's okay to lie, cheat, steal, and even kill, right? Well, no, it's not. But the temptation can be great if you think the contest is critical and you might get away with it.

Beware the Garsch Point. It's okay to be happy to be leading in the polls, but it ought to be less a time for celebrating than a time for doubling down on honest and honorable effort. And maybe for not letting your enemy know your full strength.

I've written here several times about Tom Lehrer, the Harvard-educated mathematician/musician/comedian whose That Was the Year That Was was one of my favorite childhood albums. (Another was Music, a Part of Me, a collection of oboe works by David McCallum—yes, that David McCallum—but that's another story.)

Although I've frequently replayed some of my favorite Lehrer songs, such as Pollution and New Math and The Elements, this particular song is one I probably haven't heard since I was in my teens. Nonetheless, I could still sing much of it from memory, even though it wasn't until now that I finally understood the line about Schubert and his lieder!

Whatever Became of Hubert? needs no commentary, although it's enhanced if you know a little about the Lyndon Johnson years.

Every important question is complex.

I'm as appalled as anyone at the irreversible mutilation being done to children by their parents and their doctors, under the guise of "gender-affirming care"—a term that's as bizarre an example of doublespeak as George Orwell ever dreamt of. Parents and doctors, abetted by teachers! Three of the strongest forces in life charged with keeping children safe! Surely this inversion of reality is one of the greatest horrors of our day.

And yet. And yet. It doesn't take much thinking to realize that societies, over all time and all places, have had a very inconsistent view of what, actually, is considered mutilation.

As a child, I remember seeing pictures (probably in the National Geographic magazine) of African women with huge wooden disks in their lips or ears, their bodies having been stretched since childhood by inserting disks of gradually increasing size. I called it mutilation; they called it fashion.

Not that many years ago, the Western world was horrified by the practice in many cultures of female circumcision, dubbing it "female genital mutilation," and putting strong negative pressure on countries where it was common. As recently as 2016 we saw billboards in the Gambia attacking the practice, and I was in agreement. But who was I—who is any outsider—to burden another culture with the norms of my own? Cultures can and sometimes should change, but from within, not imposed by outsiders.

What about male circumcision? That has been practiced for many millennia, in divergent cultures, and is far less drastic than the female version. If we'd had sons, I don't think we would have had them circumcized, there being no religious reason to do so—but when I was a child, it was the norm for most boys in America, regardless of religious affiliation. By the time my own children came along, there was a strong and vocal movement to eliminate male circumcision. Where are those folks now, when we are routinely removing a lot more than foreskins?

Okay, how about piercings? Tattoos? Frankly, I call both of them mutilation. Obviously, a large number of people disagree with me.

Some cultures in the past had no problem with "exposing" unwanted babies, leaving them to die—unless some kindly, childless couple found them and raised them as their own, thus creating the foundation for centuries of future folk tales and novels. We in America can hardly cast stones at those societies, given how few of our own unwanted babies live long enough to have a chance to be rescued.

Where do you draw the line? Maybe between what adults do of their own free will, and what adults do to children who are not yet capable of making informed decisions? Yet there are parents who have the ears of their babies pierced, or disks put into their lips, or parts of their genitals removed, and the societies they live in have no problem with that.

Where do you draw the line? I agree it's a complex and difficult issue.

All I know is that if America has become a place where parents, doctors, and teachers—those we trust most to do no harm to children—are facilitating the removal of young children's genitals, flooding their bodies with dangerous drugs, and encouraging them to believe that this is the best course of action for their mental health, then we haven't just crossed a line—we've fallen off a cliff.

Permalink | Read 1108 times | Comments (3)

Category Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Here I Stand: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I am a woman.

There are some who say I am not, but I have two wonderful children and two separate DNA tests to prove it.

Since childhood, I have thoroughly disliked the color pink, curling my hair, letting my hair grow long, wearing makeup, skirts, dresses, or anything fancy or frilly.

That doesn't make me any less a woman.

I hate romance novels (except those written by my friend, Blair Bancroft). I'm much more a mystery or straight science fiction (think Isaac Asimov, or Robert Heinlein's juveniles) kind of person.

That doesn't make me any less a woman.

All my life I've been interested in (and good at) math and science. When I was a child, I did play with dolls on occasion, but you'd have been much more likely to find me reading, climbing trees, or exploring in the woods next to our home.

That doesn't make me any less a woman.

I firmly believe that the abortion procedure, while necessary under a few, very rare circumstances, is the deliberate and horrific taking of an innocent human life, as well as being one of the most egregious acts of self-harm there is. (Every abortion has at least two victims, both of whom need our compassion.)

This, too, does not make me any less a woman, though there are many who deny it, in language similar to President Biden's regrettable comment, "If you have a problem figuring out whether you’re for me or Trump, then you ain’t black."

I fought enthusiastically in my youth for the right of women to participate in activities that were traditionally male-dominated. (I was the "first/only girl" several times in high school and college, which was far from easy.) Nonetheless, when the time came, I willingly and joyfully gave up a high-paying computer job in order to nurse, rear, and educate our children full time, not to mention make a home, support my husband, feed our family, and yes, Hillary Clinton, bake cookies.

That definitely doesn't make me any less a woman, although again, many people think so. They go further—many see me as less than human, or at least as an inferior sort of human, because of my chosen profession.

So stop. Just stop, all those of you who presume to speak for women, or to know what a woman is supposed to think, say, and do, or how she should vote.

A woman is defined by her gametes, and her DNA. Not by her career, her likes and dislikes, what she wears, her opinions—and above all not her politics.

The women's movement was supposed to take us out of our cages, not force us into cages of a different color.

I am a woman, and I have two children and two DNA tests to prove it.

What many people don't understand about dementia is that it can be inconsistent. For a period of time, sometimes even years, those who are losing their faculties can occasionally hold themselves together long enough to fool all but those closest to them—even doctors.

So it doesn't surprise me that President Biden pulled off a brilliant political move.

He couldn't stop his former friends and fellow Democrats from forcing him to resign his candidacy, but his revenge was quick and sharp: he immediately and enthusiastically passed the torch to Vice President Kamala Harris.

If I were a gambler, I'd bet heavily that that move was not in the plans of his betrayers. I don't know who they had in mind to take Biden's place, but I'm pretty sure they could have done better than Kamala Harris; certainly they must resent having had to give up their smoke-filled-room negotiations.

Way to go, Joe.